Navigating Parenting in Pediatric Oncology: Merging Psychodynamic Theory and Evidence-Based Practice

Abstract

Highlights

- Parenting a child with cancer often leads to permissiveness and overprotection, which may hinder emotional resilience and coping.

- Integrating Winnicott’s psychodynamic theory with evidence-based practices helps to clarify how balancing parental responsiveness and structure supports healthier child outcomes during illness.

- A dialectical approach to parenting—balancing empathy and boundaries—is essential for fostering children’s emotional development in oncology settings.

- Health professionals can better support families by promoting “good-enough parenting,” helping parents manage guilt while encouraging the child’s autonomy and adaptive coping.

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

Clinical Example: Challenges in Parenting an Ill Child

2. Good-Enough or Preoccupied?

Clinical Example: The Preoccupied Parent

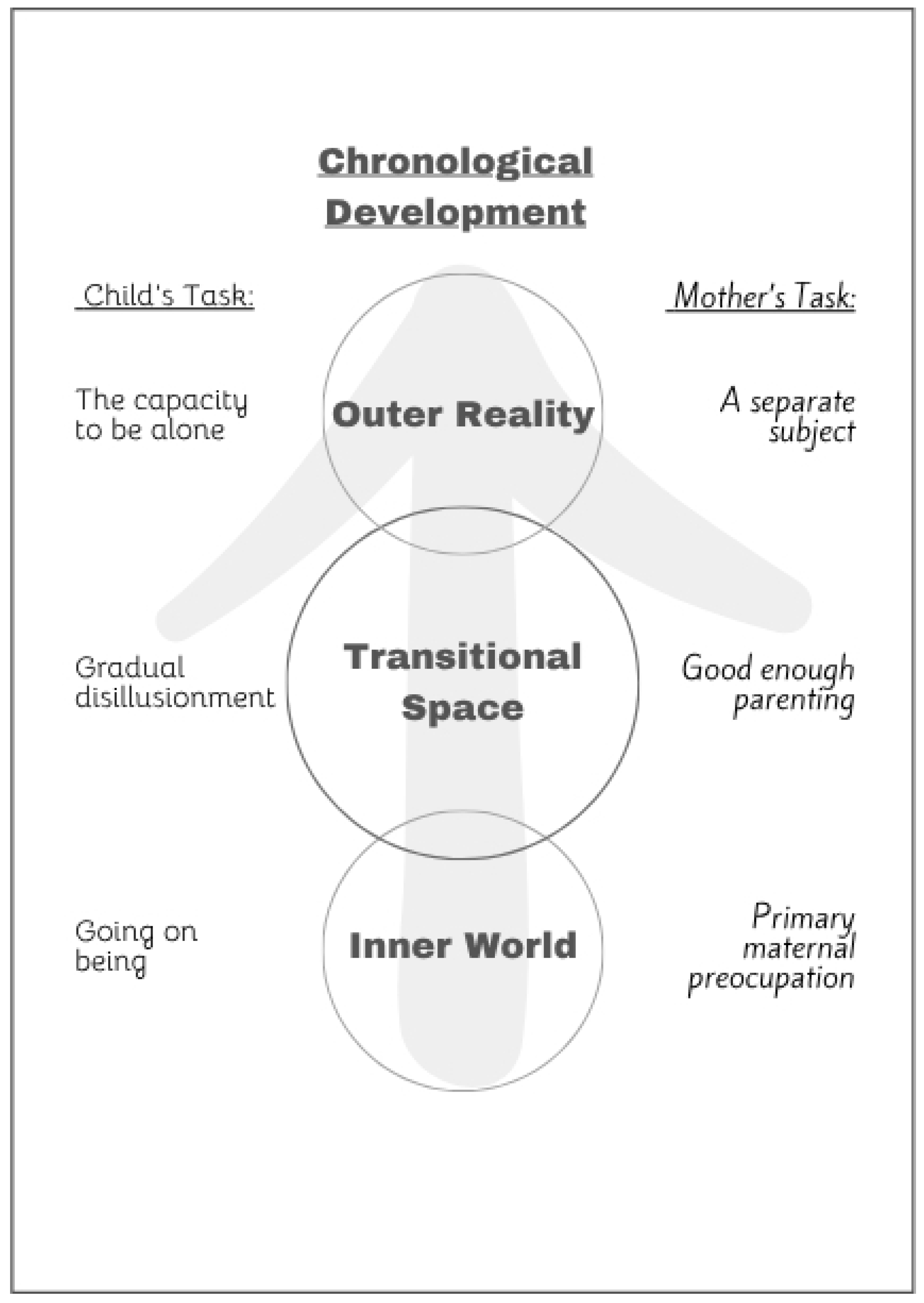

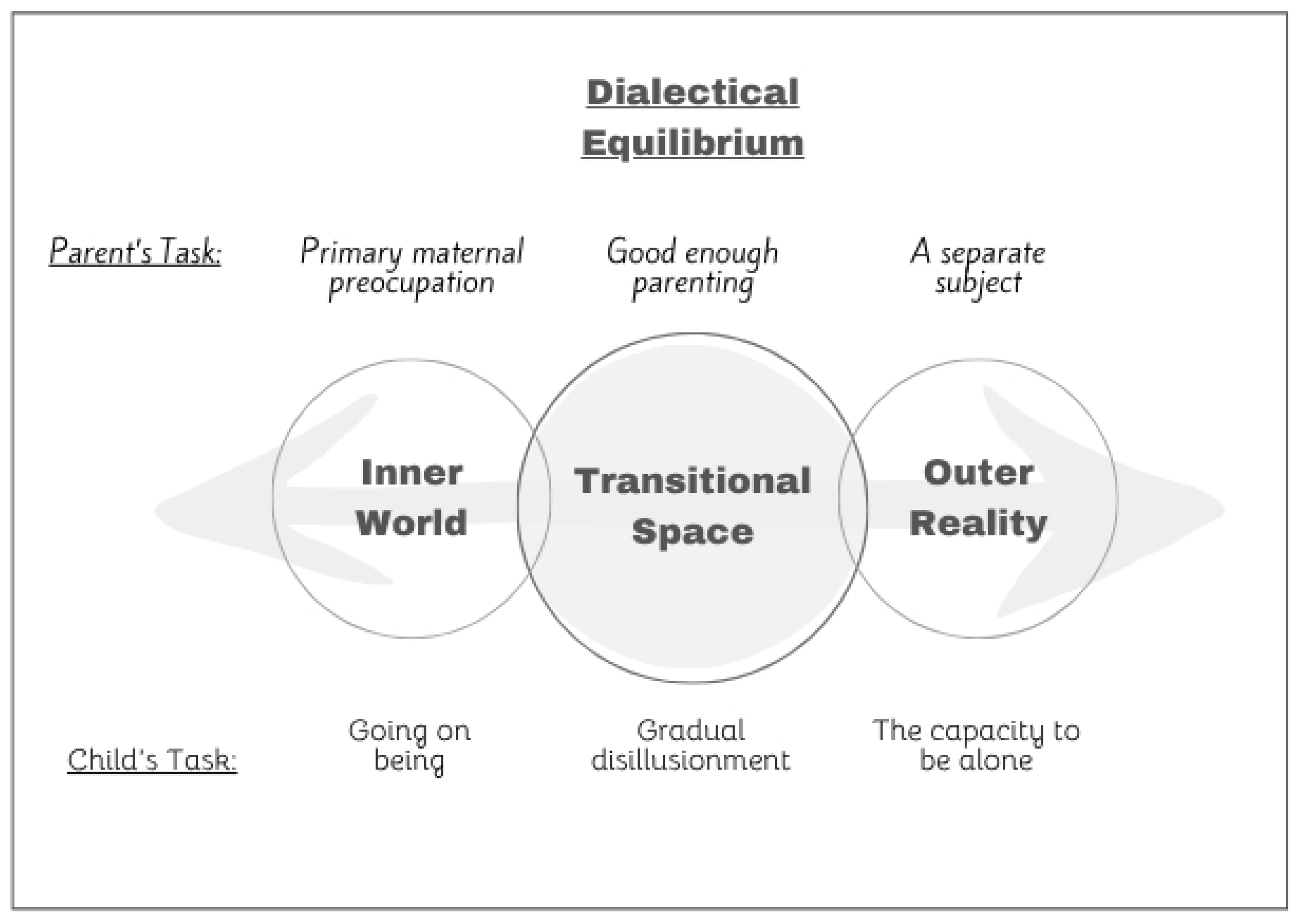

3. A Dialectical View of Good-Enough Parenting

3.1. Clinical Example: The Dialectical Proposition

3.2. Clinical Example: Incermental Change

4. Discussion: A Dialectical Approach to Good-Enough Parenting

- Cultural Considerations

- 2.

- Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Validate first, then set one clear limit. Empathically name the child’s feeling before introducing a brief, developmentally appropriate demand.

- Use micro-doses of frustration. Start with a 30-s delay or one physiotherapy repetition; lengthen only after success.

- Narrate the dialectic aloud. Say, “I see you’re scared and we can do this together.”

- Debrief with staff. Align nurse and physician scripts so the same limit is upheld across shifts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marsac, M.L.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Delahanty DLWidaman, K.; Barakat, L.P. Posttraumatic Stress Following Acute Medical Trauma in Children: A Proposed Model of Bio-Psycho-Social Processes During the Peri-Trauma Period. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 17, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremolada, M.; Bonichini, S.; Aloisio, D.; Schiavo, S.; Carli, M.; Pillon, M. Post-traumatic stress symptoms among mothers of children with leukemia undergoing treatment: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncol. 2013, 22, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E.; Abrams, A.N.; Banks, J.; Christofferson, J.; DiDonato, S.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Kupst, M.J. Psychosocial assessment as a standard of care in pediatric cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2007, 49, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Do the parent–child relationship and parenting behaviors differ between families with a child with and without chronic illness? A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccoby, E.E.; Martin, J.A. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Handbook of Child Psychology; Mussen, P.H., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 4, pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind, D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. J. Early Adolesc. 1991, 11, 56–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, B.J.; Markey, C.N.; Ericksen, A.J.; Kwasman, A.; Ortiz, R.V. Health promotion for parents. In Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 5. Practical Issues in Parenting, 2nd ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2002; pp. 311–328. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L. A behavioral scientist looks at the science of adolescent brain development. Brain Cogn. 2010, 72, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, L.L.; Wolfe-Christensen, C.; Pai, A.L.; Carpentier, M.Y.; Gillaspy, S.; Cheek, J.; Page, M. The relationship of parental overprotection and perceived child vulnerability to depressive symptomatology in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: The moderating influence of parenting stress. Child. Health Care 2004, 33, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Xu, L.; Pan, Y.; He, C.; Huang, Y.; Xu, H.; Dong, C. Family Resilience, Parenting Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment of Children With Chronic Illness: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 646421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Brähler, E.; Klein, E.M.; Jünger, C.; Wild, P.S.; Faber, J.; Schneider, A.; Beutel, M.E. Parenting in the face of serious illness: Childhood cancer survivors remember different rearing behavior than the general population. Psycho-Oncol. 2019, 28, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankri, Y.L.; Ben-Ari, A. Between Primary Maternal Preoccupation and Exposure Therapy: From Challenges in Integrative Treatment of Children with PTSD to a Reexamination of Transitional Space. Int. J. Integr. Psychother. 2021, 12, 8–27. Available online: https://www.integrative-journal.com/index.php/ijip/article/view/146?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Winnicott, D.W. The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1960, 41, 585–595. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13785877 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Winnicott, D.W. The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment: Studies in the Theory of Emotional Development; International Universities Press: Oxford, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. Playing and Reality; Tavistock Publications: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.R.; Mitchell, S.A. Object Relations in Psychoanalytic Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. The Art of Loving; Harper Collins: London, UK, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, T.H. The Matrix of the Mind: Object Relations and the Psychoanalytic Dialogue; (Original work published 1986); Jason Aronson: Lanham, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Tustin, F. Autistic States in Children; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Balint, M. The Basic Fault: Therapeutic Aspects of Regression; Tavistock Publications: London, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Kohut, H. Self-Psychology and the Humanities: Reflections on a New Psychoanalytic Approach; Strozier, C.B., Ed.; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.; Lwow, E. The parent-child mutual recognition model: Promoting responsibility and cooperativeness in disturbed adolescents who resist treatment. J. Psychother. Integr. 2004, 14, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. The Passing of the Oedipus complex. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1924, 5, 419–424. Available online: https://pep-web.org/browse/IJP/volumes/5?preview=IJP.005.0419A (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Freud, S. Some psychical consequences of the anatomical distinction between the sexes. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1927, 8, 133–142. Available online: https://pep-web.org/browse/document/IJP.008.0133A?index=40&page=P0133 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Klein, M. Mourning and its relation to manic-depressive states. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1940, 21, 125–153. Available online: https://pep-web.org/browse/IJP/volumes/21?preview=IJP.021.0125A (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Kohut, H.; Seitz, P. The Search for the Self; Kohut, H., Ed.; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Volume 1, pp. 337–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bion, W.R. Second Thoughts: Selected Papers on Psycho-Analysis; Karnac Books: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, J. Shadow of the Other: Intersubjectivity and Gender in Psychoanalysis; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cousino, M.K.; Hazen, R.A. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 809–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, R.L.; Corbin, S.M.; Sturges, J.W.; Wolfe, V.V.; Prater, J.M.; James, L.D. The relationship between adults’ behavior and child coping and distress during BMA/LP procedures: A sequential analysis. Behav. Ther. 1989, 20, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, R.L.; Piira, T.; Cohen, L.L.; Cheng, P.S. Pediatric procedural pain. Behav. Modif. 2006, 30, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voll, M.; Fairclough, D.L.; Morrato, E.H.; McNeal, D.M.; Embry, L.; Pelletier, W.; Noll, R.B.; Sahler, O.J.Z. Dissemination of an evidence-based behavioral intervention to alleviate distress in caregivers of children recently diagnosed with cancer: Bright IDEAS. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Alpert-Gillis, L.; Feinstein, N.F.; Crean, H.F.; Johnson, J.; Fairbanks, E.; Small, L.; Rubenstein, J.; Slota, M.; Corbo-Richert, B. Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: Program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics 2004, 113, e597–e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.E.; Simms, S.; Barakat, L.; Hobbie, W.; Foley, B.; Golomb, V.; Best, M. Surviving Cancer Competently Intervention Program (SCCIP): A cognitive-behavioral and family therapy intervention for adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families. Fam. Process 1999, 38, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicott, D.W. Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1953, 34, 89–97. Available online: https://pep-web.org/browse/document/ijp.034.0089a (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Ellis, D.A.; Podolski, C.L.; Frey, M.A.; Naar-King, S.; Wang, B.; Moltz, K. The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: Impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.E.; Lewis, C. The role of parent-child relationships in child development. In Developmental Science: An Advanced Textbook, 6th ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Lamb, M.E., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, 2011; pp. 469–516. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Steinberg, L. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.J.; Gustafson, K.E. Adaptation to Chronic Childhood Illness; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi, C. Family, Self, and Human Development Across Cultures: Theory and Applications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M.; Kauser, R. Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2018, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ankri, Y.L.E.; Ben-Ari, A. Navigating Parenting in Pediatric Oncology: Merging Psychodynamic Theory and Evidence-Based Practice. Children 2025, 12, 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101395

Ankri YLE, Ben-Ari A. Navigating Parenting in Pediatric Oncology: Merging Psychodynamic Theory and Evidence-Based Practice. Children. 2025; 12(10):1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101395

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnkri, Yael L. E., and Amichai Ben-Ari. 2025. "Navigating Parenting in Pediatric Oncology: Merging Psychodynamic Theory and Evidence-Based Practice" Children 12, no. 10: 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101395

APA StyleAnkri, Y. L. E., & Ben-Ari, A. (2025). Navigating Parenting in Pediatric Oncology: Merging Psychodynamic Theory and Evidence-Based Practice. Children, 12(10), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101395