Testicular Cancer Education—Hidden Potential Ways to Improve Awareness and Early Diagnosis in Young Men?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

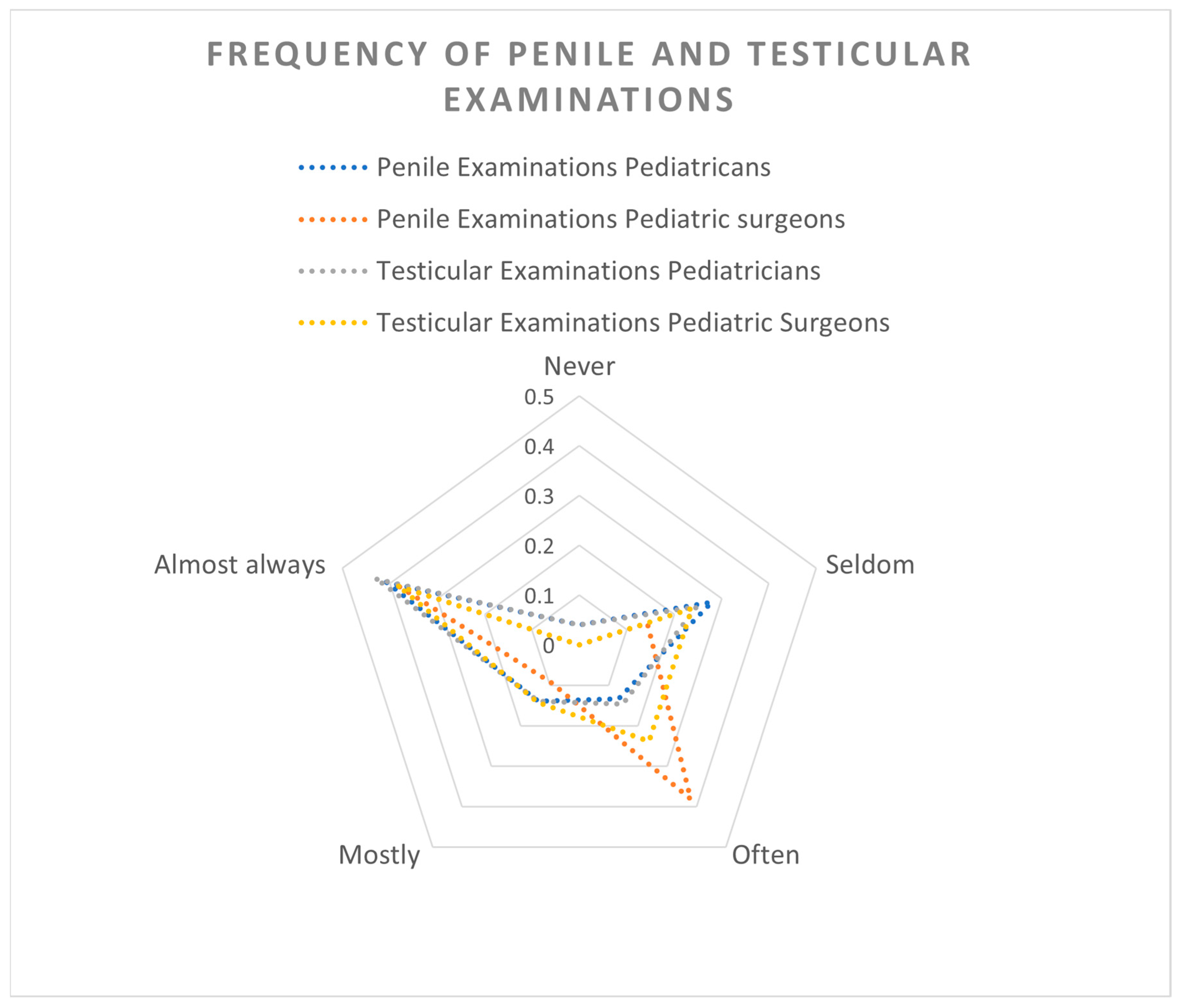

3.2. Testicular Cancer Diagnosis and Examinations

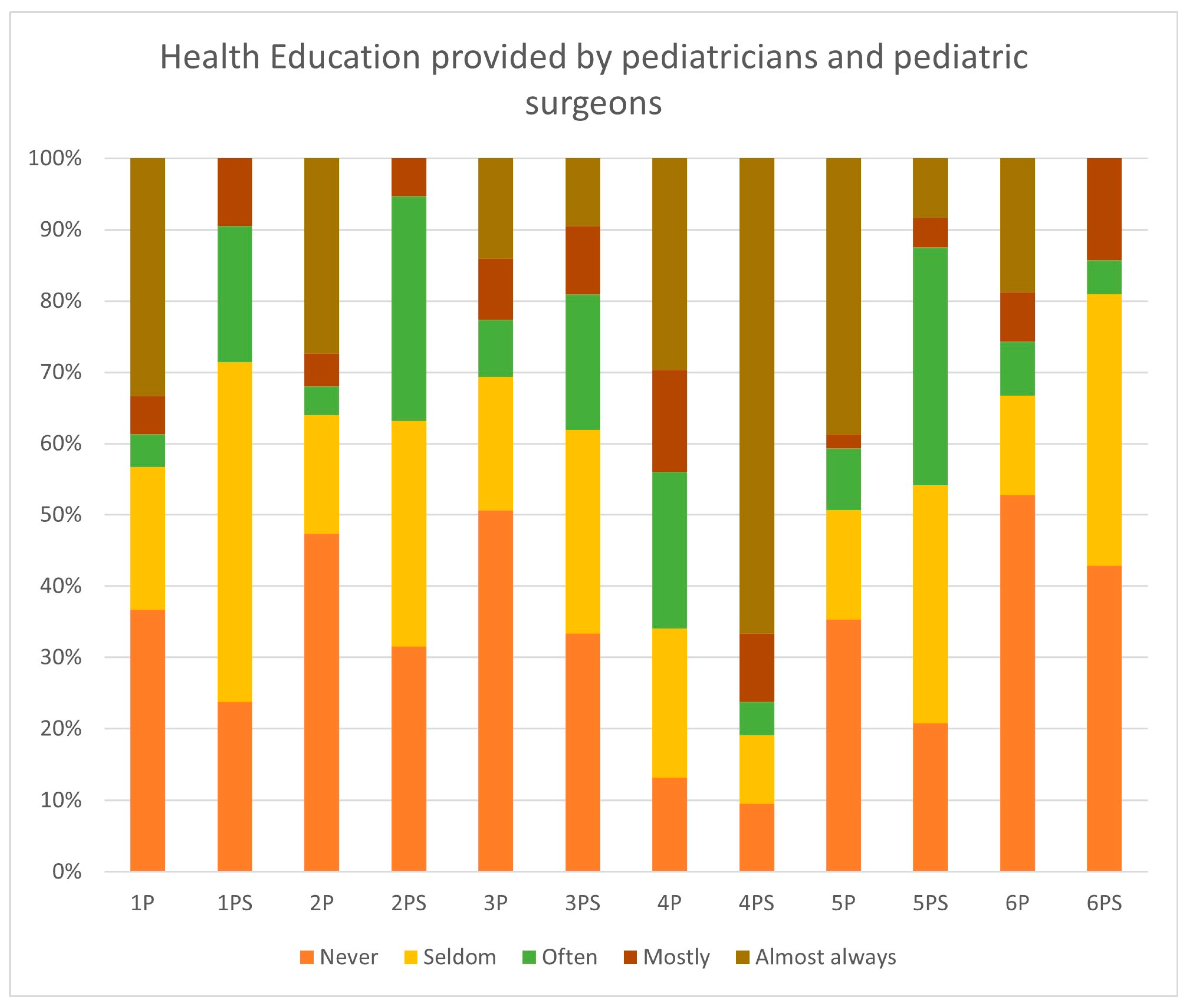

3.3. Health Education

3.4. Knowledge of Testicular Cancer Among Male Children and Adolescents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten. Hodenkrebs (Hodenkarzinom) ICD-10: C62. Available online: https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Krebsarten/Hodenkrebs/hodenkrebs_node.html (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Cassaro, F.; Arena, S.; Bonfiglio, R.; Alibrandi, A.; D’Antoni, S.; Romeo, C.; Impellizzeri, P. Utility of Clinical Signs in the Diagnosis of Testicular Torsion in Pediatric Age: Optimization of Timing in a Time-Sensitive Pathology. Children 2025, 12, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Chan, S.C.; Tin, M.S.; Liu, X.; Lok, V.T.; Ngai, C.H.; Zhang, L.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.J.; et al. Worldwide Distribution, Risk Factors, and Temporal Trends of Testicular Cancer Incidence and Mortality: A Global Analysis. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez Isabel, M.A.; Gómez Fraile, A.; Aransay Brantot, A.; López Vázquez, F.; Delgado Munos, M.D.; Encinas Goenchea, A.; Matute de Cárdenas, J.A.; Berchi García, F.J. Tumores testiculares en la infancia. Revisión de 13 años. Cir. Pediatr. Organo Soc. Esp. Cir. Pediatr. 1996, 9, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzyk, Ł.; Denisow-Pietrzyk, M.; Czeczelewski, M.; Ślizień-Kuczapski, K.; Torres, K. Cancer education matters: A report on testicular cancer knowledge, awareness, and self-examination practice among young Polish men. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, C.; Kitsos, E. Transitions From Pediatric to Adult Care. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2017, 4, 2333794X17744946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcell, A.V.; Burstein, G.R. Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Services in the Pediatric Setting. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20172858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnyloskurenko, G.; Erler, T.; Sybilski, A.; Saltykova, H.; Mityuryayeva, I.; Kostiuk, O.; Avvakumova, O.A. Preventive examinations of children in different countries: Similarities and differences. Wiad. Lek. 2022, 75 Pt 1, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Improving the Health and Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents: Guidance on Scheduled Child and Adolescent; UNICEF: New York City, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, C.A.; Jeong Kim, S.; Phillips, D.; Bhatia, V.; Janzen, N.; Gerber, J.A. Urologic practice patterns of pediatricians: A survey from a large multisite pediatric care center. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1278782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, J.A.; Balasubramanian, A.; Jorgez, C.J.; Shukla, M.A.; Jacob, J.S.; Zhu, H.; Sheth, K.R.; Mittal, A.; Tu, D.D.; Koh, C.J.; et al. Do pediatricians routinely perform genitourinary examinations during well-child visits? A review from a large tertiary pediatric hospital. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2019, 15, 374.e1–374.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamtsiuris, P.; Bergmann, E.; Rattay, P.; Schlaud, M. Inanspruchnahme medizinischer Leistungen. Ergebnisse des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007, 50, 836–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, J.; Kloft, J.; Jones, J.; John, P.; Khoder, W.; Mahmud, W.; Vallo, S. Das Bewusstsein bezüglich der klinischen Relevanz von bösartigen Hodentumoren unter Studierenden Der Stellenwert von Aufklärungskampagnen. Der Urologe. Ausg. A 2019, 58, 790–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cieślikowski, W.A.; Kasperczak, M.; Milecki, T.; Antczak, A. Reasons behind the Delayed Diagnosis of Testicular Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuck Cancer. Be Ballsy: Take Your Health into Your Own Hands. Available online: https://www.letsfcancer.com/be-ballsy (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Saab, M.M.; Landers, M.; Hegarty, J. Promoting Testicular Cancer Awareness and Screening: A Systematic Review of Interventions. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 178 (100%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | n = 64/178 (36%) |

| Female | n = 114/178 (64%) |

| Age (years) | |

| <25 | n = 0/178 (0%) |

| 25–34 | n = 21/178 (11.8%) |

| 35–44 | n = 41/178 (23%) |

| 45–54 | n = 60/178 (33.7%) |

| 55–64 | n = 50/178 (28.1%) |

| 65–74 | n = 5/178 (2.8%) |

| >74 | n = 1/178 (0.6%) |

| Specialty | |

| Pediatrician | n = 150/178 (84.3%) |

| Pediatric Surgeon | n = 21/178 (11.8%) |

| Not specified | n = 7/178 (3.9%) |

| Place of employment | |

| Solo practice | n = 47/178 (26.4%) |

| Multiphysician practice | n = 65/178 (36.5%) |

| Children’s hospital | n = 50/178 (28.1%) |

| University children’s hospital | n = 16/178 (9%) |

| Qualification | |

| Trainee | n = 21/178 (11.8%) |

| Specialist | n = 157/178 (88.2%) |

| Work experience (years) | |

| <5 | n = 20/178 (11.2%) |

| 5–10 | n = 20/178 (11.2%) |

| 11–20 | n = 53/178 (29.8%) |

| 21–30 | n = 49/178 (27.5%) |

| >30 | n = 36/178 (20.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kidess, M.; Goedeke, J.; Aschl, F.; Pyrgidis, N.; Volz, Y.; Georgieva, T.; Stredele, R.; Ebner, B.; Atzler, M.; Askari, D.; et al. Testicular Cancer Education—Hidden Potential Ways to Improve Awareness and Early Diagnosis in Young Men? Children 2025, 12, 1380. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101380

Kidess M, Goedeke J, Aschl F, Pyrgidis N, Volz Y, Georgieva T, Stredele R, Ebner B, Atzler M, Askari D, et al. Testicular Cancer Education—Hidden Potential Ways to Improve Awareness and Early Diagnosis in Young Men? Children. 2025; 12(10):1380. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101380

Chicago/Turabian StyleKidess, Marc, Jan Goedeke, Franz Aschl, Nikolaos Pyrgidis, Yannic Volz, Troya Georgieva, Regina Stredele, Benedikt Ebner, Michael Atzler, Darjusch Askari, and et al. 2025. "Testicular Cancer Education—Hidden Potential Ways to Improve Awareness and Early Diagnosis in Young Men?" Children 12, no. 10: 1380. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101380

APA StyleKidess, M., Goedeke, J., Aschl, F., Pyrgidis, N., Volz, Y., Georgieva, T., Stredele, R., Ebner, B., Atzler, M., Askari, D., Heinrich, M., Becker, K., Hermans, J., Marcon, J., Apfelbeck, M., Muensterer, O., Stief, C. G., & Chaloupka, M. (2025). Testicular Cancer Education—Hidden Potential Ways to Improve Awareness and Early Diagnosis in Young Men? Children, 12(10), 1380. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101380