Gastrointestinal Dystonia in Children and Young People with Severe Neurological Impairment & Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Highlights

- This study is the first systematic review of the evidence for the management of gastrointestinal dystonia in patients with palliative care needs.

- High certainty evidence is currently lacking, but a significant body of indirect ev-idence exists upon which initial suggestions for practice and further study can be based.

- Gastrointestinal dystonia is a heterogeneous condition for which a well co-ordinated, holistic, multidisciplinary approach to management is required.

- Clear identification of goals of care, use of advance care planning, and a rational, systematic approach to symptom management are the mainstay of the treatment approach.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Review Question

1.2. Population

1.3. Interventions

1.3.1. Pharmacological

- Omeprazole, lansoprazole, ranitidine, famotidine, domperidone, and Gaviscon;

- Metoclopramide, erythromycin, levomepromazine, cyclizine, ondansetron, granesitron, stemetil, nabilone, other cannabinoids, aprepitant, and baclofen;

- Gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, clonidine, SSRI- Fluoxetine, Duloxetine, diazepam, midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, clobazam, and chloral hydrate;

- Opioids (morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, dihydrocodeine, and buprenorphine, methadone) and ketamine;

- Lactulose, movicol, enemas, docusate, sodium picosulfate, and senna;

- Alimemazine, octreotide, Neostigmine, pyridostigmine, cyproheptadine, H. Pylori treatment, and probiotics;

- Over-the-counter remedies: [peppermint tea/oil];

- PN/TPN, home TPN/PN, and fluids IV/SC.

1.3.2. Non-Pharmacological

- Pyridostigmine treatment, Farrell bag, flatus tube, Replogle tube, nasogastric feeding, jejunal feeding, and gastrostomy venting;

- Hydrolysed formulas, alterations of feeding regimen, blended diet, exclusion diets, feed thickeners, and carbogel;

- Psychological intervention, distraction therapy, music therapy, art therapy, play therapy, complementary therapies, acupuncture, hydrotherapy, reflexology, and abdominal massage;

- Place of care, access to tissue viability, bed and seating cushions, mattresses including airflow, oral care and hygiene, over feeding, formula osmolarity, and feeding rate reduction.

1.3.3. Comparison

- Placebo, no treatment/usual care, cross comparison between any of the above (within group and between group), combinations of the above—reducing triggers and pharmacological management, routes of administration (same drug or same drug class).

1.3.4. Outcomes

- Reduced frequency or intensity of gut-related symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting, retching, bloating, gastric losses, constipation, or diarrhoea);

- Reduced distress as experienced by child and family;

- Supporting individualised family choice around the most appropriate use of hydration and nutrition;

- Establishing new goals of care and accepting changes in care goals;

- Potential improvement in gut motility and/or improved feed tolerance;

- Care in place of choice;

- Improved patient and family experience/carer satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

Developing Suggestions for Practice and Further Study

3. Results

3.1. Observational Non-Comparative Studies

3.2. Indirect Primary Studies

3.3. Reviews and Consensus Studies

- Use of the advanced care planning process to determine goals of care and support decision making;

- Use of home symptom management plans to guide caregivers in managing symptoms.

- Avoid over-feeding and calorie excess;

- Trial of 30% reduction in feed volume for 2–4 weeks;

- Bolus feeds of less than 15 mL/kg/feed, continuous feeds less than 8 mL/kg/h;

- Trial of continuous feeding/continuous nocturnal feeding with daytime boluses;

- Trial of hydrolysed or elemental formula;

- Trial of whey-based formula to improve gastric emptying;

- Avoidance of hyperosmolar feeds;

- Trial of blended diet;

- Gastrostomy tube venting to reduce distention;

- Gabapentin or pregabalin or a tricyclic antidepressant for visceral hyperalgesia and central pain;

- Clonidine to reduce pain from gastric and colonic distention;

- Prokinetic drug to be tried prior to jejunal feeding;

- Consider trial of alimemazine in retching/vomiting;

- Consider trial of cyproheptadine in retching/vomiting;

- Consider trial of Neurokinin receptor antagonist (e.g., aprepitant) in retching/vomiting;

- Review medications to avoid polypharmacy where possible.

- Jejunal tube feeding trial as an alternative to fundoplication and gastrostomy feeding for children with severe gastro-oesophageal reflux with risk of aspiration.

3.4. Evidence to Decision Process

4. Suggestions for Practice and Further Study

4.1. General Approach to Management

- An overall clinical lead should be identified to coordinate the multiple teams involved in managing a patient with gastrointestinal dystonia [8]. (consensus view of study development group) Gastrointestinal dystonia is a multidimensional diagnosis with several teams involved in management. Establishing clear leadership and regular multidisciplinary team meetings is the mainstay of management of gastrointestinal dystonia [8].

- Agree goals of care with the family and multidisciplinary team involving the nutrition team, neurology, and palliative care at diagnosis and points of deterioration [8]. (consensus view of study development group).

- An advance care planning process should be started at diagnosis of gastrointestinal dystonia with patients, their caregivers, and the wider multidisciplinary team [2]. (very low-quality evidence). Using an advance care planning process to support goal setting and decision-making is integral to ensuring clear, goal-driven management and avoiding harmful interventions or futile treatment trials. Advance care planning involves a series of discussions between the child, caregivers, and the medical team to gain a joint understanding of the condition, wishes, hopes, fears, and uncertainties, and create plans in the event of deteriorating health. It is not unusual for a number of plans to be made to cater for a variety of scenarios as the child’s condition progresses. Topics for discussion include the following:

- Ensuring a shared understanding of the child’s condition, natural history, and expected disease trajectory.

- Understanding with wishes, goals, fears, hopes, and anxieties of the child and family as treatment progresses.

- Agreeing management of distressing symptoms and developing an associated ‘symptom management plan’ to guide caregivers in managing symptoms in the community.

- Agreeing management of episodes of acute deterioration in health, including assessment at home or in hospital and escalation of life-sustaining treatment as appropriate.

- Agreeing management of gradual deterioration should it become clearer that the child will not survive.

- Considering wishes of the child and caregivers with regard to end of life care and discussing changes to the body, location of care, adjustments made to medications and treatment, and post death wishes.

- Discussing support needs of the child and family [28].

- Clear symptom management plans should be developed with caregivers to guide the assessment and management of distressing symptoms in the community and who to call for advice or support if required (consensus view of the study development group). Symptom management plans may include the following:

- ▪

- Clear description of the symptom, and how it presents for that specific child;

- ▪

- Initial non-pharmacological approaches to managing the symptom in a safe space;

- ▪

- Pharmacological management of the acute symptom including dose frequency of any medications given;

- ▪

- Next steps if initial steps are ineffective;

- ▪

- Who to call for advice or support if symptoms persist despite the above measures [28].

4.2. Initial Management of Gastrointestinal Dystonia

- Ensure optimal management of gastro-oesophageal reflux, spasticity, muscular dystonia, secretions, and constipation prior to treatment directed at gastrointestinal dystonia (consensus view of study development group) [21]. Children with severe neurological impairment often have multiple sources of pain and distress [26,29]. These should be fully assessed and excluded or treatment optimised prior to treatment directed specifically at gastrointestinal dystonia (consensus view of study development group). If hip or spine pain, spasticity, or gastroesophageal reflux disease is poorly controlled, management of gastrointestinal dystonia will likely be ineffective as significant triggers for pain and distress remain unaddressed.

- Where possible, medications known to impact gastrointestinal motility, such as anticholinergics (trihexyphenidyl, tricyclic antidepressants, hyoscine hydrobromide/butylbromide), specific opioids (morphine, diamorphine, oxycodone, etc.), and serotonin receptor antagonists (ondansetron/granisetron) should be weaned or removed if possible (consensus view of study development group).

- Avoid over-estimating fluid and calorie requirements based on weight, length, weight z-scores, and BMI alone, as this may lead to excess feed being administered and impair tolerance. Assessment by a dietician with experience working with children with severe neurological impairment is advised (very low-quality evidence) [21].

- Consider reducing overall feed quantity per day to a point where tolerance is achieved to manage symptoms (very low-quality evidence) [18].

- Develop a plan to manage anxiety and agitation alongside symptoms of gastrointestinal dystonia. This may include use of clonidine or a short-acting benzodiazepine (such as midazolam) enterally or oral-transmucosally (if faster onset of action is required) alongside psychological interventions and management of the environment and caregiver anxiety/distress (consensus view of the study development group).

- Children and young people with severe neurological impairment are especially sensitive to environmental factors (noise, lighting, and emotion) and the emotions of their primary caregivers during periods of symptom occurrence. Ensuring a clear plan for psychosocial and spiritual factors for the patient and caregivers is an essential part of management. This requires a multidisciplinary approach [26] (consensus view of the study development group).

4.3. Pharmacological Management of Pain

- Alongside simple analgesics such as paracetamol enterally or rectally, consider a gabapentinoid first line for pain in gastrointestinal dystonia (very low-quality evidence) [13,14,15]. Gabapentin has been demonstrated to be effective for managing pain in patients with severe neurological impairment and is recommended as first-line for central pain, visceral hyperalgesia, and pain of unknown origin [15]. It is well tolerated and has been reported to improve feed tolerance. The impact of opioids on motility precludes their use as long-acting agents in the management of early gastrointestinal dystonia (consensus view of the study development group).

- Consider the addition of clonidine enterally if pain symptoms persist [31]. Clonidine acts as an antineuropathic agent to reduce visceral hypersensitivity, as well as an anxiolytic. Although relative bradycardia and hypotension have been noted with its use in a variety of indications, there is no evidence that these lead to clinical deterioration when national prescribing guidelines are followed [31]. Clonidine may be used enterally, transmucosally, transdermally, or intravenously (consensus view of the study development group).

- Opioids should generally be avoided as first-line medications due to the impact on gastrointestinal motility. However, a variety of synthetic opioids known to be less constipating may be considered. These include buprenorphine and fentanyl (both available transdermally). Should morphine/oxycodone or other more constipating opioids be used, consider the concurrent use of a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist to reduce the impact of constipation (consensus view of the study development group).

- Third line antineuropathic agents may be used under specialist advice for the management of pain. These include ketamine enterally or parenterally or methadone enterally or parenterally [29]. The effectiveness of newer agents for neuropathic pain, such as oxycarbazepine and lacosamide, in GID, is yet to be established (consensus view of the study development group). Seek specialist advice.

4.4. Pharmacological Management of Retching and Vomiting

- Nausea, vomiting, and retching may be as a result in the following factors:

- Damage to brain areas involved in the vomiting reflex and emesis generation.

- Gastrointestinal dysmotility, including delayed gastric emptying.

- Autonomic dysfunction.

- Visceral hypersensitivity of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux, cough, and secretion clearance due to impaired swallowing.

- Emetogenic medications.

- Pain.

- Psychological factors.

- Consider a prokinetic first-line for management of upper gastrointestinal symptoms (very low-quality evidence) [20].

- Management of visceral hypersensitivity and pain may be required for resistant symptoms of retching/vomiting (very low-quality evidence) [18]. Autonomic dysregulation, visceral hyperalgesia, and impaired gut motility underlie much of the distress related to the upper gastrointestinal tract in children with severe neurological impairment.

- Antiemetics acting on the chemoreceptor trigger zone and vomiting centre of the brain may be used with caution, for example, levomepromazine and neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists (consensus view of the study development group). Avoid antiemetics with high anticholinergic activity (hyoscine hydrobromide/butylbromide/cyclizine) or those otherwise negatively impacting on gut motility (serotonin receptor antagonists ondansetron/granisetron) (consensus view of the study development group).

- Once the above approaches have been trialed if symptoms persist consider a trial of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Nabilone) under specialist advice.20 (very low quality evidence) [27].

4.5. Pharmacological Management of Lower Gastrointestinal Symptoms

- History of chronic constipation leading to alterations in bowel compliance;

- Upper motor neurone damage leading to sphincter dysfunction;

- Autonomic dysfunction;

- Visceral hyperalgesia;

- Intestinal dysmotility;

- Medications leading to impaired peristalsis.

- ▪

- With regard to constipation, painful defecation, and intermittent intestinal obstruction symptoms in children with gastrointestinal dystonia, national guidance for the management of constipation in children should be followed in the first instance [21,32] (consensus view of the study development group). The caveat to this is the impact of upper motor neuron damage on sphincter activity in the gut in children with severe neurological impairment. Due to this, active bowel management using suppositories and enemas may be needed alongside enteral management [21] (very low-quality evidence).

- ▪

- Use of regular suppositories and/or enemas early in management to help regulate bowel movements and reduce episodes of distressing unpredictable bowel opening/flatus (very low-quality evidence) [21].

- ▪

- ▪

- There is insufficient evidence or experience to recommend the use of linaclotide for this group of patients. Linaclotide is a guanylate cyclase-c agonist, increasing secretion of ions and water into the GI tract. Seek specialist advice (consensus view of the study development group).

4.6. Bloating, Flatulence

- Management of bloating usually improves as a result of optimisation of the symptoms discussed above and alterations to enteral feed described previously. Probiotics may be considered as a trial for 8–12 weeks while enteral feed is tolerated, and a course of treatment for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth may be of benefit (consensus view of the study development group). Peppermint tea or oil can be of benefit, according to some families, though evidence is lacking. Use of regular suppositories as above for managing constipation may improve the regulation of flatulence causing discomfort [21].

4.7. Agitation and Anxiety

- Management of agitation and anxiety is vital, as these play a key role in distress expressed by children with GID (consensus view of the study development group).

- Management of anxiety should be included in symptom management plans for pain or distress episodes. A combination of comfort measures a rapid-onset (fentanyl) or immediate-release analgesic alternating with a rapid-acting benzodiazepine (e.g., buccal midazolam) may be required to manage both pain and anxiety components of distress episodes. Seek specialist advice for more detailed management (consensus view of the study development group).

4.8. Clinically Assisted Hydration and Nutrition

- Decisions around the use of clinically assisted nutrition or hydration are challenging and complex. Cesacion of feeds and initiation of parental nutrition may reduce symptoms related to GID.(very low quality of evidence) [8,9]. Parenteral nutrition may be started acutely during episodes of illness or acute severe distress associated with feed intolerance. In these instances there may not be time to consider fully the implications if treatment is continued longer term. In addition, for the child with complete feed intolerance, continuing on parenteral nutrition may seem to be the only option facing families and professionals when the alternative of palliation is unbearable. The parent representative on our study group emphasised the value of parenteral nutrition in facilitating periods of good quality life, using the example of her son, who survived for a number of years with total parenteral nutrition at home. This view is consistent with the findings from Rapoport et al., who reported that parents’ perception that their child’s quality of life was poor was an important prerequisite to considering withdrawal of hydration and nutrition [35]. However, our parent was clear that the burdens of long term parenteral nutrition were significant, including central line care and infection risk, liver complications, and ultimately witnessing her child’s neurological decline continuing despite the nutritional support. The study development group agreed that the correct approach should be focusing on the individual needs, wishes, and values of the child and family, considering what can be practically provided given local resources, and with reference to robust ethical frameworks and advice. Support for all involved is vital, including medical and nursing teams involved in decision making (consensus view of the study development group).

- Parents needed to feel ready for discussions. Parents felt ready for discussions when they perceived their child’s quality of life as poor. They needed to recognise their child as on a trajectory towards dying.

- The child’s physician should communicate the discussions and ethical justification to families.

- Parents valued time to consider the decisions.

- Parents valued physicians sharing their prior experiences of similar cases with them.

- Parents valued professionals being clear and confident in the views of the medical team when recommending withdrawal of hydration and nutrition (the importance of a clinical lead and strong multidisciplinary team engagement with regular meetings).

- Parents valued the ability to give their child some form of comfort feeding if tolerated [35].

- ▪

- Any trial of assisted hydration or nutrition, especially parenteral nutrition for gastrointestinal dystonia, should be started with agreement on goals of care and timescale of the trial, considering benefits and harms of treatment, and implications of provision for quality of life and location of care [4,8,9] (very low-quality evidence). Decisions regarding clinically assisted hydration and nutrition are particularly pertinent in gastrointestinal dystonia. Clinically assisted nutrition includes intravenous feeding and feeding by nasogastric tube and by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and radiologically inserted gastrostomy (RIG) feeding tubes. Clinically assisted hydration can also be provided by intravenous or subcutaneous infusion of fluids [36]. In line with guidance from the UK General Medical Council and Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, artificial hydration and nutrition may be initiated or withdrawn on the basis of a multidisciplinary assessment of best interests with a clear timeframe and review point [36,37,38].

- ▪

- Nutrition and hydration interventions should be assessed separately [36].

- ▪

- The advance care planning process should be underway with agreed goals of care before starting a trial of parenteral nutrition, or if parenteral nutrition is started during an acute illness, as soon as practically possible (consensus view of the study development group).

- ▪

- Starting parenteral nutrition is not appropriate where it does not meet agreed goals of care or where the overall burdens outweigh the benefits. This may include the burden to the child and family of remaining in the hospital (consensus view of the study development group).

- ▪

- In a situation of disagreement between caregivers and professionals, hospital legal teams will be able to advise on next steps if a second opinion, clinical ethics review, or use of mediation services does not lead to an agreed path forward.(consensus view of the study development group)

4.9. End-of-Life Care

- In the sad situation where it is clear that a patient is likely to die in days or short weeks, it is important that discussions are had pre-emptively with the caregivers specifically about hydration and nutrition at the end of life (consensus view of the study development group). The reduction or withdrawal of artificial hydration and nutrition is highly emotive for families and professionals.

- As the child’s condition deteriorates towards the end of life, goals of care shift more completely towards comfort and control of distressing symptoms and away from nutrition and growth. It may be appropriate to slow down gastrointestinal motility as obstructive symptoms progress. This approach would usually involve discontinuing prokinetic agents, placing gastric feeding tubes on drainage if still in place, and using anticholinergic and antisecretory medications (consensus view of the study development group).

- Offer advice and support if caregivers wish to persist with enteral feeding and it brings pleasure to the patient, even if considered a risk or ineffective, so long as this does not cause the child distress (consensus view of the study development group).

4.10. Future Research

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.I.; Bell, E.F.; Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Walsh, M.C.; Hale, E.C.; Newman, N.S.; Schibler, K.; Carlo, W.A.; et al. Neonatal Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants From the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

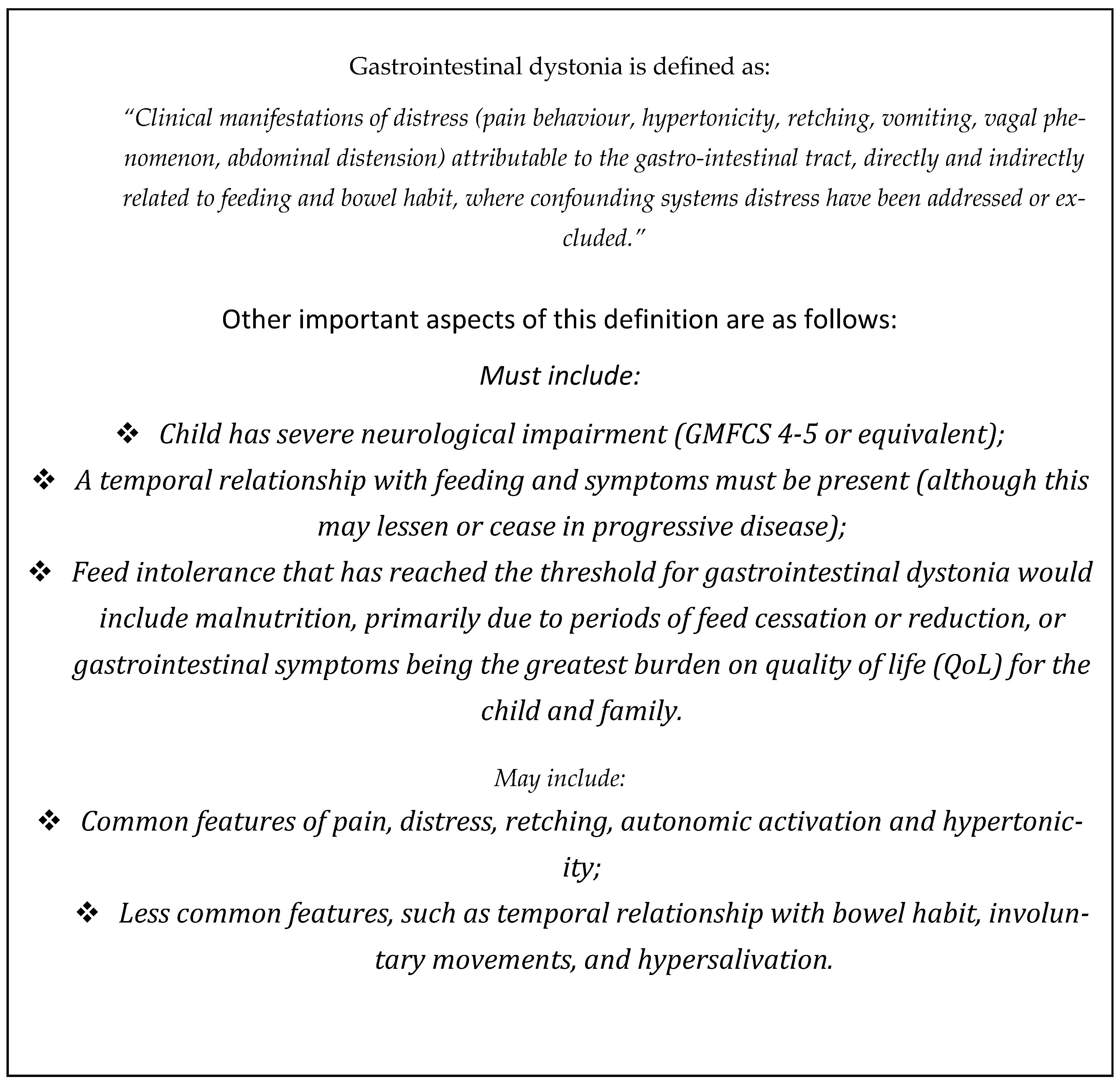

- Barclay, A.; Meade, S.; Richards, C.; Warlow, T.; Lumsden, D.; Fairhurst, C.; Paxton, C.; Forrest, K.; Mordekar, S.; Campbell, D.; et al. O13 Working definition of gastrointestinal dystonia of severe neuro-disability; outcome of the BSPGHAN/BAPM/BAPS/APPM/BPNA appropriateness panel. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022, 13, A9–A10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, A.R.; Henderson, P.; Gowen, H.; Puntis, J. The continued rise of paediatric home parenteral nutrition use: Implications for service and the improvement of longitudinal data collection. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, N.T.; Cooper, M.S.; Kularatne, A.; Prebble, A.; McGrath, K.H.; McCallum, Z.; Antolovich, G.; Sutherland, I.; Sacks, B.H. Intractable Feeding Intolerance in Children With Severe Neurological Impairment: A Retrospective Case Review of Nine Children Known to a Pediatric Palliative Care Service. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2023, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutalib, M. Parenteral nutrition in children with severe neurodisability: A panacea? Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 736–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Setting Standards for the Development of Clinical Guidelines in Paediatrics and Child Health, 5th ed.; Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Vist, G.E.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Santesso, N.; Deeks, J.J.; Glasziou, P.; Akl, E.A.; Guyatt, G.H.; Cochrane GRADEing Methods Group. Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 6th ed.; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Wahid, A.M.; Powell, C.V.; Davies, I.H.; Evans, J.A.; Jenkins, H.R. Intestinal failure in children and young people with neurodisabling conditions. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 102, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, S.; Ribeiro-Mourão, F.; Bertaud, S.; Brierley, J.; McCulloch, R.; Koeglmeier, J. P-24: Outcome of Children with Intestinal Failure (IF) and Severe Neurological Impairment(NI) Treated with Parenteral Nutrition (PN) at Home. Transplantation 2021, 105, S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordekar, S.R.; Velayudhan, M.; Campbell, D.I. Feed-induced Dystonias in Children With Severe Central Nervous System Disorders. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antao, B.; Ooi, K.; Ade-Ajayi, N.; Stevens, B.; Spitz, L. Effectiveness of alimemazine in controlling retching after Nissen fundoplication. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2005, 40, 1737–1740. [Google Scholar]

- Merhar, S.L.; Pentiuk, S.P.; Mukkada, V.A.; Meinzen-Derr, J.; Kaul, A.; Butler, D.R. A retrospective review of cyproheptadine for feeding intolerance in children less than three years of age: Effects and side effects. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Mannion, R.; Broderick, A.; Hussey, S.; Devins, M.; Bourke, B. Gabapentin for the treatment of pain manifestations in children with severe neurological impairment: A single-centre retrospective review. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2019, 3, e000467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, J.M.; Wical, B.S.; Charnas, L. Gabapentin Successfully Manages Chronic Unexplained Irritability in Children With Severe Neurologic Impairment. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e519–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, J.M.; Solodiuk, J.C. Gabapentin for Management of Recurrent Pain in 22 Nonverbal Children with Severe Neurological Impairment: A Retrospective Analysis. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manini, M.L.; Camilleri, M.; Grothe, R.; Di Lorenzo, C. Application of Pyridostigmine in Pediatric Gastrointestinal Motility Disorders: A Case Series. Pediatr. Drugs 2017, 20, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coad, J.; Toft, A.; Lapwood, S.; Manning, J.; Hunter, M.; Jenkins, H.; Sadlier, C.; Hammonds, J.; Kennedy, A.; Murch, S.; et al. Blended foods for tube-fed children: A safe and realistic option? A rapid review of the evidence. Arch. Dis. Child. 2016, 102, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, J. Feeding Intolerance in Children with Severe Impairment of the Central Nervous System: Strategies for Treatment and Prevention. Children 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekaert, I.J.; Falconer, J.; Bronsky, J.; Gottrand, F.; Dall’OGlio, L.; Goto, E.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.; Kochavi, B.; Papadopoulou, A.; et al. The Use of Jejunal Tube Feeding in Children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 69, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.A. Does retching matter? Reviewing the evidence—Physiology and forces. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, C.; van Wynckel, M.; Hulst, J.; Broekaert, I.; Bronsky, J.; Dall’OGlio, L.; Mis, N.F.; Hojsak, I.; Orel, R.; Papadopoulou, A.; et al. European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Neurological Impairment. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dydyk, A.M.; Chiebuka, E.; Stretanski, M.F.; Givler, A. Central Pain Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553027/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central Sensitization: A Generator of Pain Hypersensitivity by Central Neural Plasticity. J. Pain 2009, 10, 895–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essner, B.S.; Osgood, P.T.; Perez, M.E.; Fortunato, J.E. Autonomic Nervous System and Disorders of Gut–Brain Interaction. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2025, 54, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Singh, R.; Ro, S.; Ghoshal, U.C. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in functional gastrointestinal disorders: Underpinning the symptoms and pathophysiology. JGH Open 2021, 5, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warlow, T.A.; Hain, R.D. ‘Total Pain’ in Children with Severe Neurological Impairment. Children 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.; Symonds, J.; Poole, R.; Fraser, S.; Bremner, S.; Flynn, D.; Andrews, J.; Walker, G.; Forrest, K.; Orr, V.; et al. Nabilone for the treatment of gastrointestinal dystonia for children and young people with severe neurodisabilities: A single-centre case series. Front. Gastroenterol. 2024, 16, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. End of Life Care for Infants, Children and Young People with Life Limiting Conditions: Planning and Management. 2019. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng61 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Hauer, J.; Houtrow, A.J.; AAP Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Council on Children with Disabilities. Pain Assessment and Treatment in Children with Significant Impairment of the Central Nervous System. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20171002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.; Norton, H.; Meade, S.; Richards, C.; Protheroe, S.; Samaan, M.; Barclay, A.R. OC67 Hierarchy of nutrition interventions for gastrointestinal dystonia (GASTROINTESTINAL DYSTONIA), clear consensus for the use of blenderised diet ahead of post-pyloric feeding and surgical interventions; output of the BSPGHAN/BAPS/BPNA/APPM RAND panel. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, A41–A42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, C.; Lumsden, D.; Kaminska, M.; Lin, J.-P. Clonidine use in the outpatient management of severe secondary dystonia. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]. Constipation in Children and Young People: Diagnosis and Management. [Clinical Guideline CG99]. 2017. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99 (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Emmanuel, A.V.; Kamm, M.A.; Roy, A.J.; Kerstens, R.; Vandeplassche, L. Randomised clinical trial: The efficacy of prucalopride in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction—A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, multiple n = 1 study. Aliment. Pharm. 2012, 35, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Motion, J.; Barclay, A.; Bradnock, T.; Fraser, S.; Allen, R.; Walker, G.; Flynn, D. G11 Prucalopride for treatment refractory constipation in children: A single tertiary centre experience. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022, 13, A22–A23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.; Shaheed, J.; Newman, C.; Rugg, M.; Steele, R. Parental Perceptions of Forgoing Artificial Nutrition and Hydration During End-of-Life Care. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Medical Council. Treatment and Care Towards the End of Life: Good Practice in Decision Making; General Medical Council: Manchester, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/treatment-and-care-towards-the-end-of-life (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- General Medical Council. Decision Making and Consent; General Medical Council: Manchester, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.gmc-uk.org/ethical-guidance/ethical-guidance-for-doctors/decision-making-and-consent (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Larcher, V.; Craig, F.; Bhogal, K.; Wilkinson, D.; Brierley, J. Making decisions to limit treatment in life-limiting and life-threatening conditions in children: A framework for practice. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, s1–s23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Details | Participants | Interventions | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wahid 2017 [8] UK Case report Hospital setting Dates not reported. | 13-year-old boy with life limiting condition. Cerebral Palsy (CP), epilepsy, severe learning difficulties, and autistic features. Palliative child with intestinal failure. | Central venous catheter (CVC) and total parenteral nutrition (PN). Nasogastric (NG) feeds were not tolerated and nasojejunal (NJ) feeding was also unsuccessful. | TPN was provided post-operatively and continued for five months. During this period the child did not tolerate NJ feeds. Severe gut dysmotility was confirmed throughout the remaining gut. Slow introduction of comfort feeds via NG and mouth. This gradually improved as the child started to tolerate more volume and reached full enteral feeds by 3 months. TPN may be indicated for a period of gastrointestinal rest prior to reintroduction of feeds in children with gastrointestinal failure. |

| Hill 2021 [9] Case series 2009–2019. | Six children with intestinal failure and severe neurological impairment. | Home parenteral nutrition programme. | Survival time of 3–7.8 years (median 5.5 years). “Improvement in signs, but not symptoms, reduced analgesia” “no more complications than expected”. Deaths = 4; (3 deaths unrelated to PN and 1 with central line associated bloodstream infection). |

| Indirect Evidence from Primary Studies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study ID | Methods | Population | Intervention(s) | Study results | Notes |

| Paper 1: “Feed-induced dystonias in children with severe central nervous system disorders.” S Mordekar, M Velayundhan, D Campbell. United Kingdom 2012–2017 [10] | Retrospective case series. | 12 children age 5 months–15.8 yrs (mean 9.5 yrs) patients presenting with status dystonicus with evidence of feed-induced dystonic spasms. Patient with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) or Sandifer syndrome excluded. | Withholding feeds and use of TPN to manage symptoms. Octreotide intravenously in 2 cases | Withholding feeds led to a resolution of symptoms. Restarting even 5 mL/h via gastric or jejunal tube using extensively hydrolysed/elemental or electrolyte solution led to the return of dystonia. Patients with feeds withheld experienced resolution of symptoms. | All taking anti-dystonic medications. All had pH studies, gastroscopy, and biopsies with no evidence of GORD or oesophagitis. Eight had fundoplication (confirmed to be intact). |

| Paper 2: “Effectiveness of alimemazine in controlling retching after Nissen fundoplication” Antao et al. United Kingdom December 2002–2003. [11] | Prospective double blind randomised crossover placebo-controlled study. Exclusion criteria: hepatic or renal impairment, hypothyroidism. | 15 subjects, 12 enrolled with completed diaries of retching episodes. Age 8–180 months (median 36). Patients with neurological impairment. Post-nissen fundoplication for GORD. All gastrostomy fed. | One week alimemazine, one week placebo with crossover. Alimemazine 0.25 mg/kg three times daily (max 2.5 mg per dose). | Mean number of retching episodes with alimemazine significantly reduced compared with placebo. No adverse effects of Alimemazine reported. One subject discontinued due to drowsiness. Concluded Alimemazine safe and effective for retching post-nissen fundoplication. | Recommended dosing 0.25 mg/kg three times daily. |

| Paper 3: “A retrospective review of Cyproheptadine for feeding intolerance in children less than three years of age: effects and side effects.” Merhar et al. United States 2011–2015 [12] | Retrospective chart review of children under 3yrs of age seen in neonatal follow up clinic prescribed Cyproheptadine for feed intolerance (fullness or discomfort with feeds, retching and/or abdominal distention or vomiting). | 39 children under 3 yrs. Graduates from the neonatal unit(18 with prematurity (46%) 29 with perinatal brain injury (74%)). 61% artificially tube fed, 59% by gastrostomy. 23.5% had nissen fundoplication. Most remained on an ‘acid blocker’. | Cyproheptadinemean starting dose 0.23 mg/kg/d three times daily (range 0.07–0.83 mg/kg/d). | Side effects noted: 25.6% mild sleepiness, 10.2% constipation, 7.7% behavioural tantrums increasing. 5.1%–discontinued medication. Sleepiness and constipation resolved with dose reduction. Statistically significant weight increase on treatment. Outcomes; 66.7% symptom resolution, 28.2% some improvement in symptoms, 84.6% improved vomiting. | Recommended dosing 0.5–1 mg/kg/day in three divided doses for patients <1 yr. 1–2 mg/kg/day in three divided doses for patients in older children. |

| Paper 4: “Gabapentin for the treatment of pain manifestations in children with severe neurological impairment: a single centre retrospective review” Collins et al. Ireland 2019 [13] | Single centre retrospective chart review. | 42 patients attending joint gastroenterology and palliative care services with gastrointestinal cause of pain and distress. 3–63 m age. | Gabapentin for central pain and visceral hyperalgesia. Pregabalin as second line option if gabapentin response inadequate or side effects. | Response to gabapentin good or very good overall in 60% patients. Worse in 2%. 71% noted improvement in irritability. 40% noted improvement in pain (reduced analgesia requirement) 55% no improvement, 5% undocumented. Side effects: None in 74%, reducing effectiveness in 10% (taking 60 mg/kg/d), lethargy in 7%, alopecia, twitching, vomiting, abnormal liver function tests also reported. Discontinued in 36% with 80% of these switched to pregabalin. | Not clear what criteria was used for good or very good effect apart from notes report. No objective measures used. Also included patients with irritability of unknown origin as well as those with gastrointestinal symptoms. |

| Paper 5 “Gabapentin Successfully Manages Chronic Unexplained Irritability in Children With Severe Neurologic Impairment” Hauer JM, Wical BS, Charnas L. 2006 United states 2006. [14] | Retrospective single centre case series | Nine patients age 9 m—22 yrs with severe neurological impairment and irritability. Population had feed intolerance and irritability associated with feeds, defecation and flatus. Suspected due to visceral hypersensitivity. Six out of nine gastrostomy tube fed, seventh scheduled for gastrostomy. | Gabapentin | All cases had upper gastrointestinal endoscopy several had PH studies with no significant pathology. All tried acid suppression with no improvement. Eight out of nine were treated successfully for constipation. Marked improvement with gabapentin trial. 5 mg/kg/dose once daily at night, increased every 3–7 days final doses 15–35 mg/kg/day in three divided doses. Improved irritability, crying, feed tolerance, sleep, and improved responsiveness. | One child who discontinued treatment had a good response to amitriptyline. No objective data to measure ‘marked improvement’. |

| Paper 6 “Gabapentin for Management of Recurrent Pain in 22 Nonverbal Children with Severe Neurological Impairment: A Retrospective Analysis” Hauer JM, Solodiuk JC. 2015 United States 2011–2014 [15] | Single Centre Retrospective study case note review. | 22 patients with severe neurological impairment in long term paediatric care facility with recurrent pain behaviours recorded on Individualised numeric rating scale (INRS). 64% had gastrointestinal symptoms. Mean age 11.4 yrs (range not given but up to 27 yrs). | Gabapentin 5–6 mg/kg/day increased every 2–3 days to maximum 72 mg/kg/d or until symptoms improved. (Mean dose required 43 mg/kg/day.) All on medication for gastric acid suppression. | Significant benefit (>50% reduction in frequency and severity) in recurrent pain behaviours in 21 patients (95%). Some improvement in dystonia also noted. Some had a decrease in vomiting, two who were jejunely fed were able to return to gastric feeding, weight gain noted in some.’ No significant side effects—mild transient sedation in a few. | Criteria for benefit used was if two or more bedside nurses reported the patient to have greater than 50% benefit along with decrease in frequency and severity of episodes irritability. (Pain frequency determined by the use of ‘as required’ analgesics.) |

| Paper 7 “Application of Pyridostigmine in paediatric gastrointestinal motility disorders: A case series.” Manini ML, Camilleri M, Grothe R, Lorenzo CD. United States 2017 [16] | Retrospective case series. | Heterogeneous population. Case series with one relevant case of child with severe neurological impairment and feed intolerance 7 yrs old. | Distention and poor motility despite laxatives. Pyridostigmine 10 mg four times daily (4 mg/kg/day) reduced to 2 mg/kg/day maintenance. | Significant increase in frequency of bowel opening (from every 5 days to daily). Vomiting and abdominal distention improved. Feed tolerated at 50 mL/h over 20 h daily. Weight gain continued. Stopping pyridostigmine lead to symptom recurrence. | |

| Reviews and Other Non-Primary Sources | |||||

| Study ID | Methods | Population | Intervention(s) | Main conclusions/Recommendations | |

| Review 1. “Blended foods for tube-fed children: a safe and realistic option? A rapid review of the evidence” Coad et al. 2016 United Kingdom August—December 2014 [17] | Rapid review of literature using systematic principals. PubMed, Medline, Cinahl, PsychINFO, Google Scholar. | Children and adults using blended diet as alternative feed. | Blended diet to replace commercial formula for feeds. | Significant social benefit of blended diet and parent satisfaction. Improved tolerance of greater feed volume, reduction in pain, reflux, and constipation with its use. | |

| Review 2. “Feeding intolerance in Children with Severe Impairment of the Central Nervous System.” Hauer J United States 2017 [18] | Narrative literature review and guideline. | Children with severe neurological impairment and feed intolerance. | Multiple | Multiple, including: Importance of home care plans for parents to follow to manage symptoms. Importance of advance care planning to manage goals of care and expectations of care. Consider 30% reduction in feed volume with monitoring of weight and symptoms to assess benefit 2–4 weeks. Bolus feeds should be <15 mL/kg/feed, continuous rate <8 mL/kg/h. Gastrostomy tube venting to reduce GI distension. Gabapentin pregabalin and tricyclic antidepressant trial for visceral hyperalgesia and central pain. Clonidine for pain perception during gastric and colonic distention. Cyproheptadine to improve feed tolerance, decrease emesis and retching post-fundoplication. | |

| Review 3: “The use of jejunal tube feeding (JTF) in children: A position paper by the Gastroenterology and Nutrition Committees of the ESPGHAN 2019.” Broekaert et al. 2019 Pan European Literature review until 2018. [19] | Systematic literature review and consensus meeting. Literature review Medline 1980–2015. PubMed and Cochrane. Evidence categorised according to GRADE. Consensus vote on recommendations. | Patients for whom jejunostomy tube feeding is a consideration. | Jejeunostomy tube insertion and management. | Decision to place jejunostomy tube should be multidisciplinary. A trial of continuous gastric feeding with hydrolysed or elemental formula should be given prior to JTF. Consider a trial of at least 1 prokinetic drug to promote oral or gastric feeding before instituting jejunal feeding. In children with severe neurological impairment JTF should be considered as an alternative to fundoplication and gastrostomy feeding where the child has severe GORD with risk of aspiration. | |

| Review 4: “Does retching matter? Reviewing the evidence—Physiology and forces.” Richards C. A. United Kingdom. 2019 [20] | Narrative literature review | Children with severe neurological impairment post antireflux surgery. | Management of retching and vomiting in post-reflux surgery patients. | Trial of whey-based feed leading to improved gastric emptying Predigested formula trial Avoid hyperosmolar feeds Consider blenderised feeds Avoid overfeeding and calorie excess Smaller more frequent boluses Continuous gastric feeds Consider jejunal feeding +/− gastric drainage Consider prokinetic (Domperidone and metoclopramide) trial Consider trial of alimemazine Consider trial of Cyproheptadine Considrer trial of Seratonin 5HT3 antagonist Consider Levomepromazine. Consider trial of Neurokinin receptor antagonist Reduce/review polypharmacy especially when many drugs present. | |

| Review 5 “European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Complications in Children With Neurological Impairment” Romano et al. Pan-european. 2017 [21] | Systematic literature review and consensus meeting. Literature review Medline 1980–2015. Consensus vote on recommendations. | Children with neurological impairment. Children with cerebral palsy referred to as the major subgroup of purpose of this document. | Management of nutrition and gastrointestinal problems in children with neurological impairment. | Optimise nutrition and avoid overhydration. Trials of feed thickener and whey-based formulas should be considered. Use of prokinetics should be reserved for uncontrolled GORD due to weak efficacy and side effects. Regular re-evaluation of efficacy. Constipation: Ensure adequate fibre and fluid intake. Initial treatment with disimpaction and osmotic maintenance agents. Macrogol and paraffin should be used in caution with those at high risk of aspiration. Enemas may be required to support faecal disimpaction alongside osmotic agents. Standard 1 kcal/mL polymeric age-appropriate formula is the appropriate first feed option For poor volume tolerance consider high energy density (1.5 kcal/mL) formula containing fibre. Blenderised diets can be used but with caution due to concerns about nutritional adequacy and safety. A combination of continuous nocturnal feeds and daytime bolus feeds should be considered in those with high caloric needs or with poor tolerance to volume. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warlow, T.; Yates, J.; Taylor, N.; Villanueva, G.; Koodiyedath, B.; McElligott, F.; Holt, S.; Anderson, A.-K. Gastrointestinal Dystonia in Children and Young People with Severe Neurological Impairment & Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101359

Warlow T, Yates J, Taylor N, Villanueva G, Koodiyedath B, McElligott F, Holt S, Anderson A-K. Gastrointestinal Dystonia in Children and Young People with Severe Neurological Impairment & Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review. Children. 2025; 12(10):1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101359

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarlow, Timothy, Jill Yates, Naomi Taylor, Gemma Villanueva, Bindu Koodiyedath, Fiona McElligott, Susie Holt, and Anna-Karenia Anderson. 2025. "Gastrointestinal Dystonia in Children and Young People with Severe Neurological Impairment & Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review" Children 12, no. 10: 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101359

APA StyleWarlow, T., Yates, J., Taylor, N., Villanueva, G., Koodiyedath, B., McElligott, F., Holt, S., & Anderson, A.-K. (2025). Gastrointestinal Dystonia in Children and Young People with Severe Neurological Impairment & Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review. Children, 12(10), 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101359