The Pelvic Support Osteotomy: A Useful Therapeutic Alternative for Chronically Unstable Hips in Children and Adolescents

Abstract

Highlights

- Pelvic support osteotomy combined with femoral lengthening effectively corrects leg length discrepancy and improves gait in children and adolescents with severely damaged hips.

- The procedure achieves significant functional improvement, with a marked reduction in Trendelenburg sign and restoration of limb length.

- Pelvic support osteotomy is a safe and viable alternative to arthrodesis or total hip arthroplasty in young patients with complex hip deformities.

- This technique should be considered in treatment planning for pediatric and adolescent patients where conventional options are limited.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

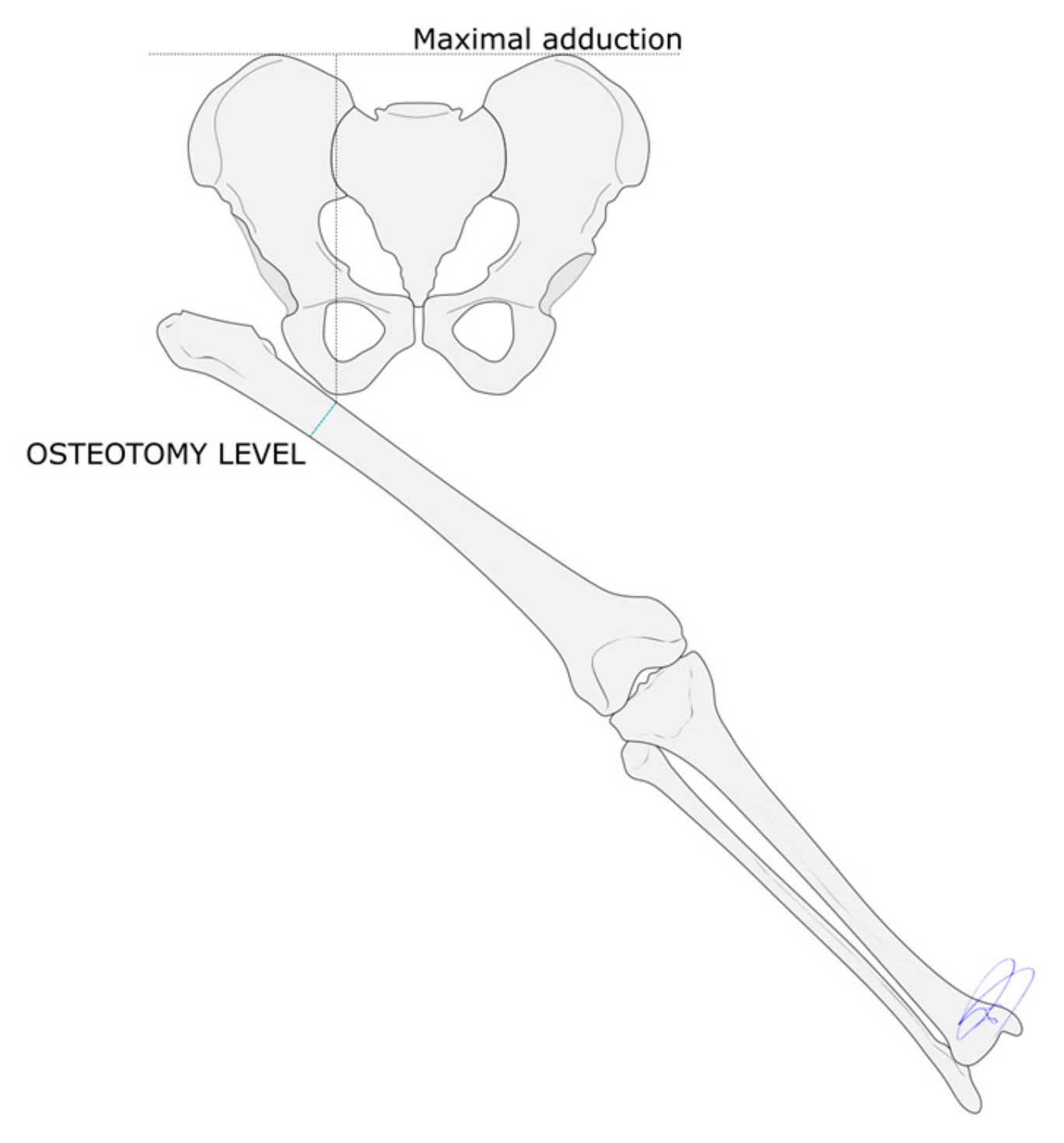

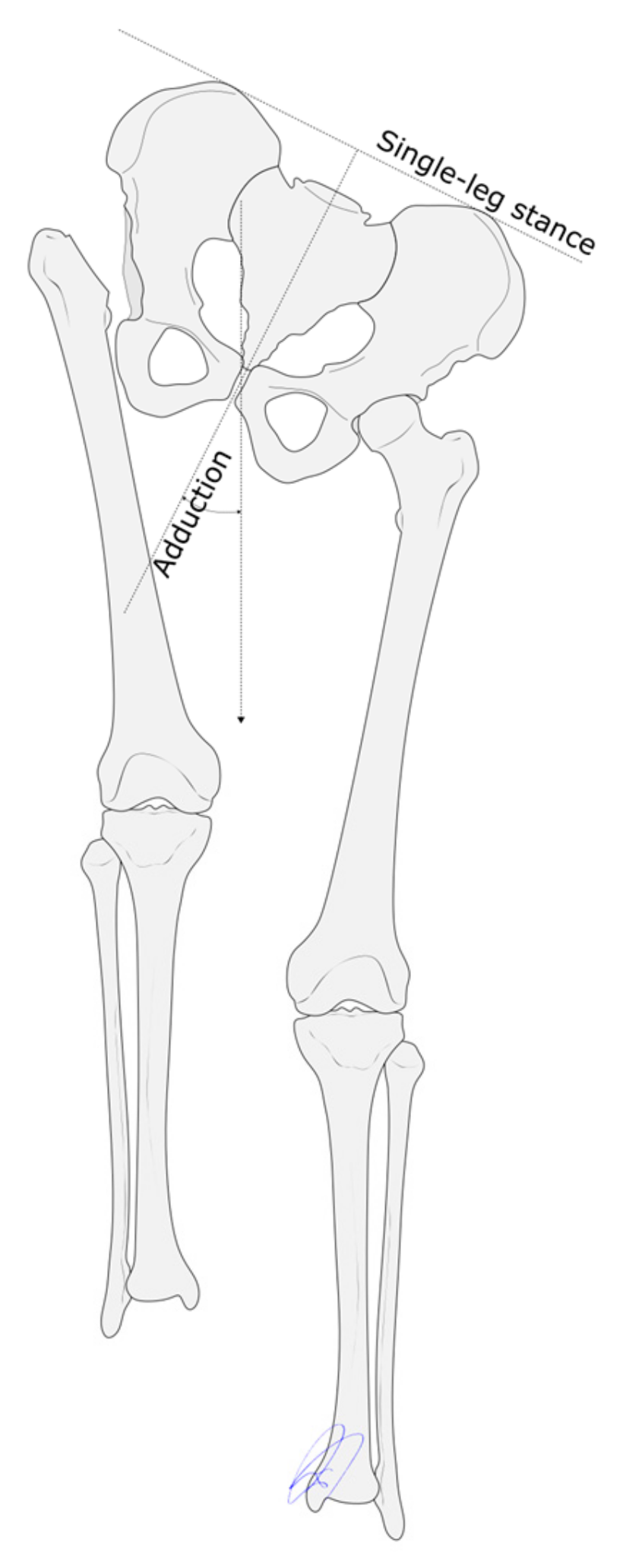

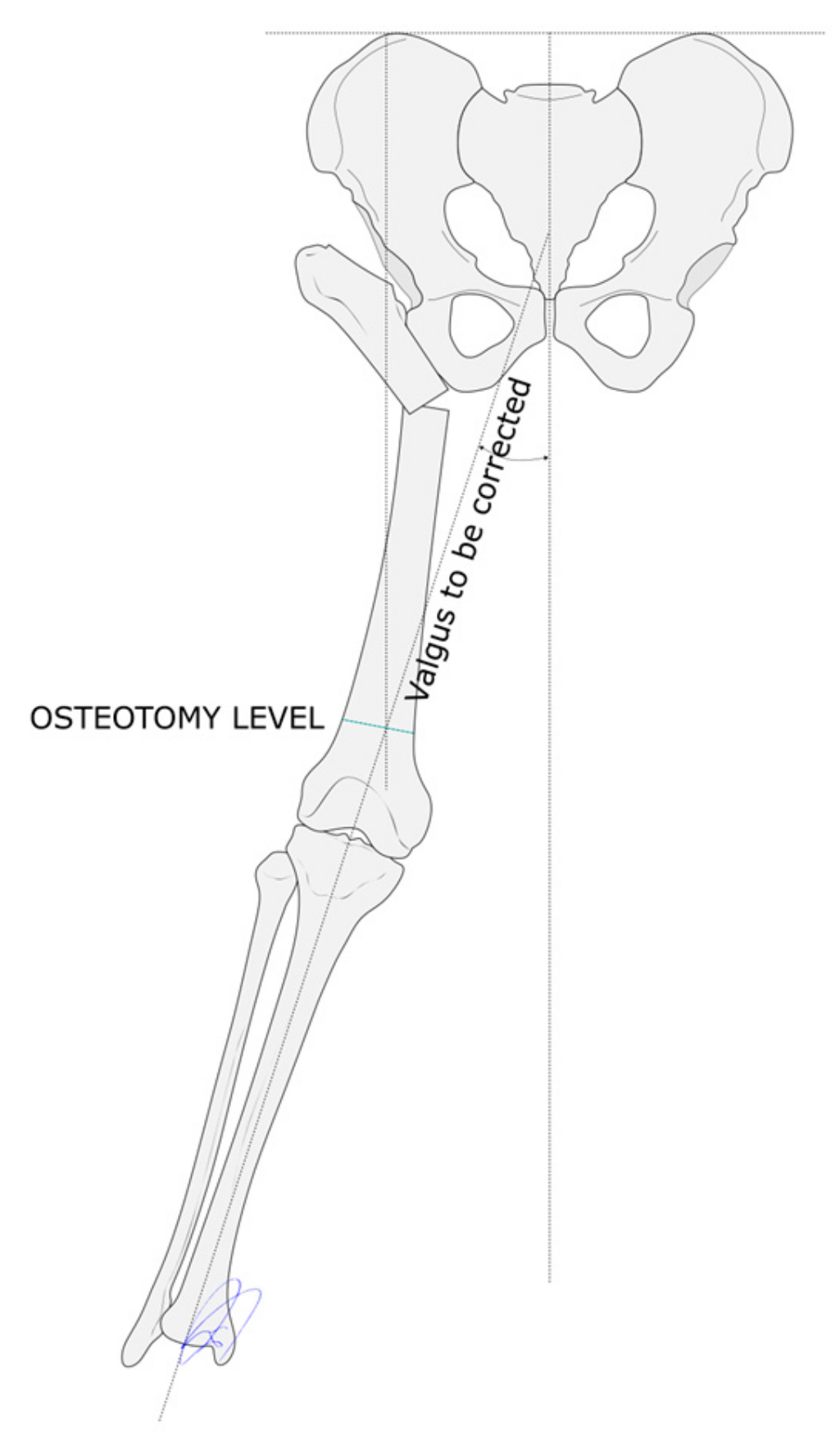

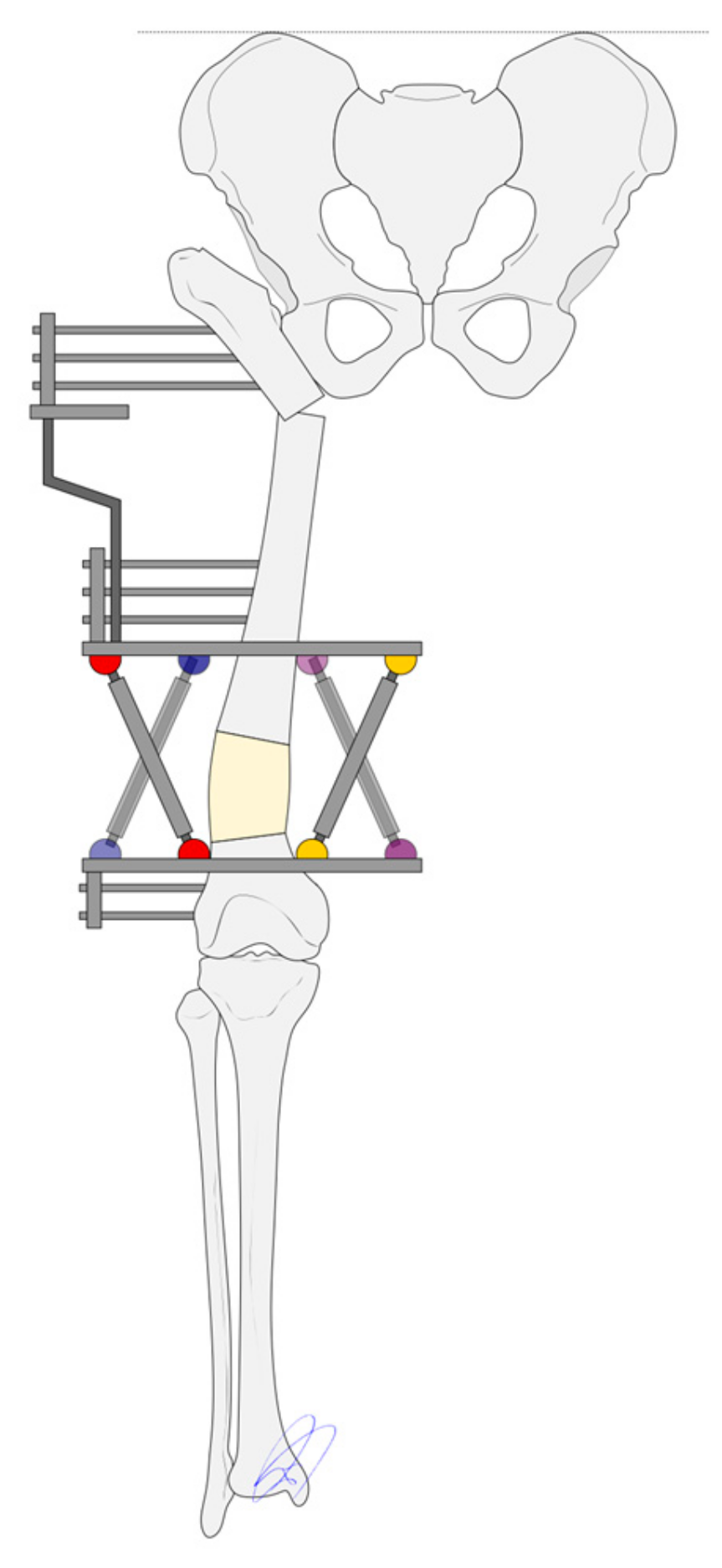

Surgical Technique

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| THA | Total hip arthroplasty |

| PSO | Pelvic support osteotomy |

References

- Gala, L.; Clohisy, J.C.; Beaulé, P.E. Hip Dysplasia in the Young Adult. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2016, 98, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.; Quadri, T.A.; Rashid, R.H. Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction Osteotomy—A Review. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 54, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pafilas, D.; Nayagam, S. The Pelvic Support Osteotomy: Indications and Preoperative Planning. Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2008, 3, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mowafi, H. Outcome of Pelvic Support Osteotomy with the Ilizarov Method in the Treatment of the Unstable Hip Joint. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2005, 71, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Umer, M.; Rashid, H.; Umer, H.M.; Raza, H. Hip Reconstruction Osteotomy by Ilizarov Method as a Salvage Option for Abnormal Hip Joints. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 835681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Yadav, A.; Raj, R.; Jha, A.; Ahuja, D.; Parihar, M. Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction—A Narrative Review. Kerala J. Orthop. 2023, 2, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kocaoglu, M.; Eralp, L.; Sen, C.; Dinçyürek, H. The Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction Osteotomy for Hip Dislocation. Acta Orthop. Scand. 2002, 73, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessette, B.J.; Fassier, F.; Tanzer, M.; Brooks, C.E. Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients Younger than 21 Years: A Minimum, 10-Year Follow-Up. Can. J. Surg. 2003, 46, 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, J.; Glorion, C.; Bonnomet, F.; Fron, D.; Migaud, H. Risk Factors for Revision of Hip Arthroplasties in Patients Younger Than 30 Years. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2011, 469, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samchukov, M.L.; Cherkashin, A.M.; Birch, J.G. Pelvic Support Osteotomy and Limb Reconstruction for Septic Destruction of the Hip. Oper. Tech. Orthop. 2013, 23, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilizarov, G.A.; Samchukov, M.L. Reconstruction of the Femur by the Ilizarov Method in the Treatment of Arthrosis Deformans of the Hip Joint. Ortop. Travmatol. Protez. 1988, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Samchukov, M.L.; Birch, J.G. Pelvic Support Femoral Reconstruction Using the Method of Ilizarov: A Case Report. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis. 1992, 52, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rozbruch, S.R.; Paley, D.; Bhave, A.; Herzenberg, J.E. Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction for the Late Sequelae of Infantile Hip Infection. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2005, 87, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.I.; Wixted, C.M.; Wu, C.J.; Hinton, Z.W.; Jiranek, W.A. Inertial Sensor Gait Analysis of Trendelenburg Gait in Patients Who Have Hip Osteoarthritis. J. Arthroplast. 2024, 39, 1741–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rosasy, M.A.; Ayoub, M.A. Midterm Results of Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction for Late Sequelae of Childhood Septic Arthritis. Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2014, 9, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, K.; Joshi, N.; Sharma, C.S.; Bhargava, R.; Meena, D.S.; Bansiwal, R.C.; Govindasamy, R. Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction in Skeletally Mature Young Patients with Chronic Unstable Hip Joints. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2011, 131, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, K.M. Pelvic Support Osteotomy in the Treatment of Patients With Excision Arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, M.A.; ElGebeily, M.A.; Ghaly, N.A.M.; Thakeb, M.F.; Hefny, H.M. Pelvic Support Osteotomy by Ilizarov’s Concept: Is It a Valuable Option in Managing Neglected Hip Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults? Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2011, 6, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, M. Evaluation of the Gluteus Medius Muscle After a Pelvic Support Osteotomy to Treat Congenital Dislocation of the Hip. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2005, 87, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiltenwolf, M.; Carstens, C.; Bernd, L.; Lukoschek, M. Late Results after Subtrochanteric Angulation Osteotomy in Young Patients. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 1996, 5, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, M.; Bowen, R.J. A Pelvic Support Osteotomy and Femoral Lengthening with Monolateral Fixator. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 440, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masquijo, J.J.; Miscione, H.; Goyeneche, R.; Primomo, C. Osteotomía de Soporte Pélvico y Elongación Femoral Distal Con Fijador Externo Monolateral. Rev. Asoc. Argent. Ortop. Traumatol. 2008, 73, 391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Gursu, S. An Effective Treatment for Hip Instabilities: Pelvic Support Osteotomy and Femoral Lengthening. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2011, 45, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Kong, L.; Wang, J.; Nie, H.; Luan, B.; Li, G. Development of Modified Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction Surgery for Hip Dysfunction Treatment in Adolescent and Young Adults. J. Orthop. Transl. 2021, 27, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanghurde, B.; Agashe, M.; Rustagi, T.; Rathod, C.; Mehta, R.; D′Silva, D.; Aroojis, A. Treatment of Unstable Hips in Children with Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction: A Retrospective Analysis of Six Cases. Paediatr. Orthop. Relat. Sci. 2017, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liang, X.; Zhao, W.; Guo, B.; Ren, L.; Qin, S.; Chen, J.; Peng, A.; Yang, H. Modified Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction in Treatment of Adolescent Hip Instability. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2019, 33, 1379–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukanaka, M.; Halvorsen, V.; Nordsletten, L.; EngesæTer, I.Ø.; EngesæTer, L.B.; Marie Fenstad, A.; Röhrl, S.M. Implant Survival and Radiographic Outcome of Total Hip Replacement in Patients Less than 20 Years Old. Acta Orthop. 2016, 87, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, M.C.; Musdal, Y. Subtrochanteric Valgus-Extension Osteotomy for Neglected Congenital Dislocation of the Hip in Young Adults. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2000, 66, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosi, R.; Marciandi, L.; Frediani, P.V.; Facchini, R.M. Uncemented Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients Younger than 20 Years. J. Orthop. Sci. 2016, 21, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- te Velde, J.P.; Buijs, G.S.; Schafroth, M.U.; Saouti, R.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; Kievit, A.J. Total Hip Arthroplasty in Teenagers: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2024, 44, e115–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kouswijk, H.W.; Bus, M.P.A.; Gademan, M.G.J.; Nelissen, R.G.H.H.; de Witte, P.B. Total Hip Arthroplasty in Children. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2025, 107, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milch, H. The “Pelvic Support” Osteotomy. 1941. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1989, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metikala, S.; Kurian, B.T.; Madan, S.S.; Fernandes, J.A. Pelvic Support Hip Reconstruction with Internal Devices: An Alternative to Ilizarov Hip Reconstruction. Strateg. Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2020, 15, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.M.; Catagni, M.A.; Guerreschi, F. Total Hip Replacement Fifteen Years after Pelvic Support Osteotomy (PSO): A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2012, 96, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Sex | Age | Side | Etiology | Necrosis | Dislocation | Stiffness | Coxa Vara | Coxa Valga | Genu Valgum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 16 | Right | Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 2 | Male | 10 | Right | (Non-tuberculous) septic arthritis | Yes | - | - | Yes | - | - |

| 3 | Male | 19 | Right | Spinal tumor-derived sciatic nerve palsy | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 4 | Female | 10 | Left | Arthrogryposis | - | Yes | - | - | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Male | 16 | Right | Developmental dysplasia of the hip | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 6 | Male | 12 | Right | Slipped capital femoral epiphysis | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 7 | Male | 10 | Right | (Tuberculous) septic arthritis | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 8 | Female | 9 | Left | (Non-tuberculous) septic arthritis | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 9 | Female | 14 | Left | Congenital short femur | - | Yes | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | Male | 16 | Right | Congenital short femur | - | Yes | - | - | - | - |

| 11 | Female | 12 | Right | (Non-tuberculous) septic arthritis | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| 12 | Male | 12 | Right | Developmental dysplasia of the hip | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | - |

| Total | 8M/4F | 13 | 9R/3L | - | 9 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Case | PreOp Leg Length Discrepancy (cm) | Lengthening (cm) | FollowUp Leg Length Discrepancy (cm) | ExFix Time (days) | ExFix Index (days/cm) | PreOp Trendelenburg | FollowUp Trendelenburg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 270 | 33.8 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 210 | 30.0 | Severe (+++) | Negative (−) |

| 3 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 360 | 36.0 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| 4 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 320 | 32.0 | Severe (+++) | Moderate (++) |

| 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 180 | 36.0 | Severe (+++) | Negative (−) |

| 6 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 210 | 30.0 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| 7 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 330 | 33.0 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| 8 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 225 | 25.0 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| 9 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 330 | 36.7 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| 10 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 240 | 34.3 | Severe (+++) | Moderate (++) |

| 11 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 210 | 30.0 | Severe (+++) | Negative (−) |

| 12 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 270 | 33.8 | Severe (+++) | Mild (+) |

| Total | 8 | 8.1 | 0.9 | 263 | 32.6 | 12 +++ | 2 ++; 7 +; 3 − |

| Movement | Stage | Degrees | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion | Preoperative | 96.7 | 0.002 |

| Follow-up | 128 | ||

| Extension | Preoperative | 7.5 | 0.006 |

| Follow-up | 24.2 | ||

| External rotation | Preoperative | 10 | 0.003 |

| Follow-up | 38.3 | ||

| Internal rotation | Preoperative | 9.2 | 0.004 |

| Follow-up | 24.2 | ||

| Abduction | Preoperative | 18.3 | 0.002 |

| Follow-up | 37.5 | ||

| Adduction | Preoperative | 12.5 | 0.003 |

| Follow-up | 22.5 |

| Case | Delayed Healing | Fracture Regenerate | Pin tract Infection | Joint Contracture | Vascular Injury | Problems | Obstacles | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | - | Yes | - | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | - | Yes | - | - | - | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Yes | Yes | - | - | - | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Yes | - | Yes | - | - | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | - | - | Yes | - | - | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | - | - | - | Yes | - | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | - | - | - | - | Yes | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | - | - | Yes | - | - | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| Study | N | Sex | Age (Mean) | Follow-Up (Months) | PostOp Leg Length Discrepancy (cm) | ExFix Time (Months) | ExFix Index (Months/cm) | Lengthening (cm) | PostOp Trendelenburg (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Umer (2014) [5] | 37 | 18 M/19F | 23.3 | - | 1.0 | - | - | - | - |

| El Mowafi (2005) [4] | 25 | 8M/17F | 22.4 | 54.0 | - | 7.0 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 20% |

| Marimuthu (2011) [16] | 12 | 7M/5F | 23.0 | 59.4 | 0.9 | 7.3 | - | - | 25% |

| Kocaoglu (2002) [7] | 14 | 2M/12F | 20.0 | 68.0 | - | 7.0 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 21% |

| El Rosasy (2014) [15] | 16 | 9M/7F | 23.0 | 85.6 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 23% |

| Inan (2005) [19] | 11 | 0M/11F | 25.2 | 36.0 | - | - | - | - | 83% |

| Rozbruch (2005) [13] | 8 | - | 11.2 | 60.0 | 0.8 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 5.7 | 25% |

| Mahran (2011) [18] | 20 | 5M/15F | 21.5 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 6.4 | - | - | 45% |

| Schiltenwolf (1996) [20] | 24 | - | 17.0 | 204.0 | - | - | - | - | 50% |

| Inan (2005) [21] | 16 | 2M/14F | 25.3 | 52.0 | 1.0 | 7.1 | - | - | 25% |

| Masquijo (2008) [22] | 13 | 7M/6F | 13.7 | 36.4 | 1.3 | 7.5 | - | - | 54% |

| Gursu (2011) [23] | 20 | - | 22.6 | 33.5 | 1.6 | 12.0 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 67% |

| Luo (2020) [24] | 17 | 5M/12F | 20.6 | 64.3 | - | - | - | - | 0% |

| Ghanghurde (2017) [25] | 6 | 5M/1F | 10.0 | 48.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | - | - | 0% |

| Wu (2019) [26] | 13 | 2M/11F | 24.2 | 31.2 | 1.5 | - | - | - | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salcedo Cánovas, C.; Martínez Ros, J.; Molina González, J.; García Paños, J.P.; Toledo García, S.; Ros Nicolás, M.J. The Pelvic Support Osteotomy: A Useful Therapeutic Alternative for Chronically Unstable Hips in Children and Adolescents. Children 2025, 12, 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101330

Salcedo Cánovas C, Martínez Ros J, Molina González J, García Paños JP, Toledo García S, Ros Nicolás MJ. The Pelvic Support Osteotomy: A Useful Therapeutic Alternative for Chronically Unstable Hips in Children and Adolescents. Children. 2025; 12(10):1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101330

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalcedo Cánovas, César, Javier Martínez Ros, José Molina González, Juan Pedro García Paños, Sarah Toledo García, and María José Ros Nicolás. 2025. "The Pelvic Support Osteotomy: A Useful Therapeutic Alternative for Chronically Unstable Hips in Children and Adolescents" Children 12, no. 10: 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101330

APA StyleSalcedo Cánovas, C., Martínez Ros, J., Molina González, J., García Paños, J. P., Toledo García, S., & Ros Nicolás, M. J. (2025). The Pelvic Support Osteotomy: A Useful Therapeutic Alternative for Chronically Unstable Hips in Children and Adolescents. Children, 12(10), 1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101330