The Experience of Breastfeeding Women During the Pandemic in Romania

Abstract

Highlights

- •

- The pandemic posed an additional psychological burden for women who breastfed during this period.

- •

- Despite elevated stress, mothers demonstrated a persistent commitment to breastfeeding; access to breastfeeding support during the pandemic remained generally limited.

- •

- Emphasizing the essential role of psychological support for breastfeeding mothers during the pandemic, facilitating both the initiation and the continuation of breastfeeding in the context of public health crises.

- •

- Highlighting the need to identify effective interventions to support mothers during public health crises.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Analysis of Data

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

References

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard|WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. (n.d.). Available online: https://covid19.who.int/table (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Press Releases—Ministry of Internal Affairs. (In Romanian). Available online: https://www.mai.gov.ro/category/comunicate-de-presa/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Ceulemans, M.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Van Calsteren, K.; Eerdekens, A.; Allegaert, K.; Foulon, V. SARS-CoV-2 infections and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in pregnancy and breastfeeding: Results from an observational study in primary care in Belgium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armenia, A.; Doina-Mihaela, M. The Psychosocial Impact of the Romanian Government Measures on the Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 1, 2021). Cent. Eur. Public Adm. Rev. 2021, 19, 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Breastfeeding and COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/breastfeeding-and-covid-19 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Brown, A.; Shenker, N. Experiences of Breastfeeding during COVID-19: Lessons for Future Practical and Emotional Support. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Luo, F.; Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Clinical Characteristics and Intrauterine Vertical Transmission Potential of COVID-19 Infection in Nine PregnantWomen: A Retrospective Review of Medical Records. Lancet 2020, 395, 809–815. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K.; Shukla, A.; Lal, P. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission Risk through Expressed Breast Milk Feeding in Neonates Born to COVID-19 Positive Mothers: A Prospective Observational Study. Iran. J. Neonatol. 2021, 12, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Favre, G.; Pomar, L.; Qi, X.; Nielsen-Saines, K.; Musso, D.; Baud, D. Guidelines for Pregnant Women with Suspected SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 652–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, H.; Alghamdi, S. Breastfeeding Experience among Mothers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, N.; Kam, R.L.; Gribble, K.D. Providing breastfeeding support during the COVID-19 pandemic: Concerns of mothers who contacted the Australian Breastfeeding Association. Breastfeed. Rev. 2020, 28, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, F.; Sobral, M.; Guiomar, R.; de la Torre-Luque, A.; Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Ganho-Ávila, A. Breastfeeding during COVID-19: A Narrative Review of the Psychological Impact on Mothers. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stube, A. Should infants be separated from mothers with COVID-19? First, do no harm. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Alderdice, F. The COVID-19 pandemic and perinatal mental health. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2020, 38, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigăran, R.G.; Botezatu, R.; Mînecan, E.M.; Gică, C.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Peltecu, G.; Gică, N. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pregnant Women. Healthcare 2021, 9, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Dong, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Duan, C.; Zhang, H.; Mol, B.W.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 among pregnant Chinese women: Case series data on the safety of vaginal birth and breastfeeding. BJOG 2020, 127, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Zheng, D.; Jiang, H.; Wei, Y.; Zou, L.; Feng, L.; Xiong, G.; Sun, G.; Wang, H.; et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnant women with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovenski, I.; Wells, N.; Evans, D. Patterns of cesarean birth rates in the public and private hospitals of Romania. Discov Public Health 2024, 21, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, A.B.; Brînzaniuc, A.; Oprescu, F.; Cherecheş, R.M.; Mureşan, M.; Dungy, C.I. A Structured Public Health Approach to Increasing Rates and Duration of Breastfeeding in Romania. Breastfeed. Med. 2011, 6, 429–432. [Google Scholar]

- Cigăran, R.G.; Peltecu, G.; Mustață, L.M.; Botezatu, R. The Psychological Impact on Romanian Women Infected with SARS-CoV-2 during Pregnancy. Healthcare 2024, 12, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python, Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0 Contributors. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, K.H.; Yip, Y.C.; Tsui, W.K. The Lived Experiences of Women without COVID-19 in Breastfeeding Their Infants during the Pandemic: A Descriptive Phenomenological Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, L.Y.; Lee, E.Y.; Coca, K.P.; Paek, S.C.; Hong, S.A.; Chang, Y.S. Impact of COVID-19 on breastfeeding intention and behaviour among postpartum women in five countries. Women Birth J. Aust. Coll. Midwives 2022, 35, e523–e529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.E.; Brockway, M.; Azad, M.B.; Grant, A.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.; Brown, A. Breastfeeding in the pandemic: A qualitative analysis of breastfeeding experiences among mothers from Canada and the United Kingdom. Women Birth J. Aust. Coll. Midwives 2023, 36, e388–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubbe, W.; Niela-Vilén, H.; Thomson, G.; Botha, E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Breastfeeding Support Services and Women’s Experiences of Breastfeeding: A Review. Int. J. Women’s Health 2022, 14, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höbek Akarsu, R.; Gunaydın, Y. Women’s Experiences of Breastfeeding During COVID-19 in Turkey: A Qualitative Study. Mod. Care J. 2023, 21, e135442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnazi, M.B.; Sartena, G.; Goldberg, M.; Zimmerman, D.; Ophir, E.; Baruch, R.; Goldsmith, R.; Endevelt, R. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breastfeeding in Israel: A cross- sectional, observational survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, E.M.; Howland, M.A.; Pando, C.; Stang, J.; Mason, S.M.; Fields, D.A.; Demerath, E.W. Maternal Psychological Distress and Lactation and Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Narrative Review. Clin. Ther. 2022, 44, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi, C.; Mosconi, L.; Wilson, A.N.; Amir, L.H.; Bonaiuti, R.; Ricca, V.; Vannacci, A. Exclusive breastfeeding and women’s psychological well-being during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 965306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gallego, I.; Strivens-Vilchez, H.; Agea-Cano, I.; Marín-Sánchez, C.; Sevillano-Giraldo, M.D.; Gamundi-Fernández, C.; Berná-Guisado, C.; Leon-Larios, F. Breastfeeding experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A qualitative study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavine, A.; Marshall, J.; Buchanan, P.; Cameron, J.; Leger, A.; Ross, S.; Murad, A.; McFadden, A. Remote provision of breastfeeding support and education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davanzo, R.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Baldassarre, M.; Mondello, I.; Soldi, A.; Perugi, S.; Giannì, J.; Colombo, L.; Salvatori, G.; Travan, L.; et al. Tele-support in breastfeeding: Position statement of the Italian society of Neonatology. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2024, 50, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Recommendations on Maternal and Newborn Care for a Positive Postnatal Experience [Internet]; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK579657/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Bartick, M.; Zimmerman, D.R.; Sulaiman, Z.; Taweel, A.E.; AlHreasy, F.; Barska, L.; Fadieieva, A.; Massry, S.; Dahlquist, N.; Mansovsky, M.; et al. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Position Statement: Breastfeeding in Emergencies. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2024, 19, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SARS-CoV-2 | Control | All Respondents | Chi2 p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 125 | 136 | 261 | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0.9414 |

| 26–35 | 66 (52.8%) | 75 (55.1%) | 141 (54.0%) | 0.7981 |

| 36–45 | 57 (45.6%) | 59 (43.4%) | 116 (44.4%) | 0.8138 |

| 46–55 | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.9663 |

| Education | ||||

| Lower education | 9 (7.2%) | 11 (8.1%) | 20 (7.7%) | 0.9708 |

| Higher education | 116 (92.8%) | 125 (91.9%) | 241 (92.3%) | 0.9708 |

| Living Environment | ||||

| Rural | 12 (9.6%) | 15 (11.0%) | 27 (10.3%) | 0.8608 |

| Urban | 113 (90.4%) | 121 (89.0%) | 234 (89.7%) | 0.8608 |

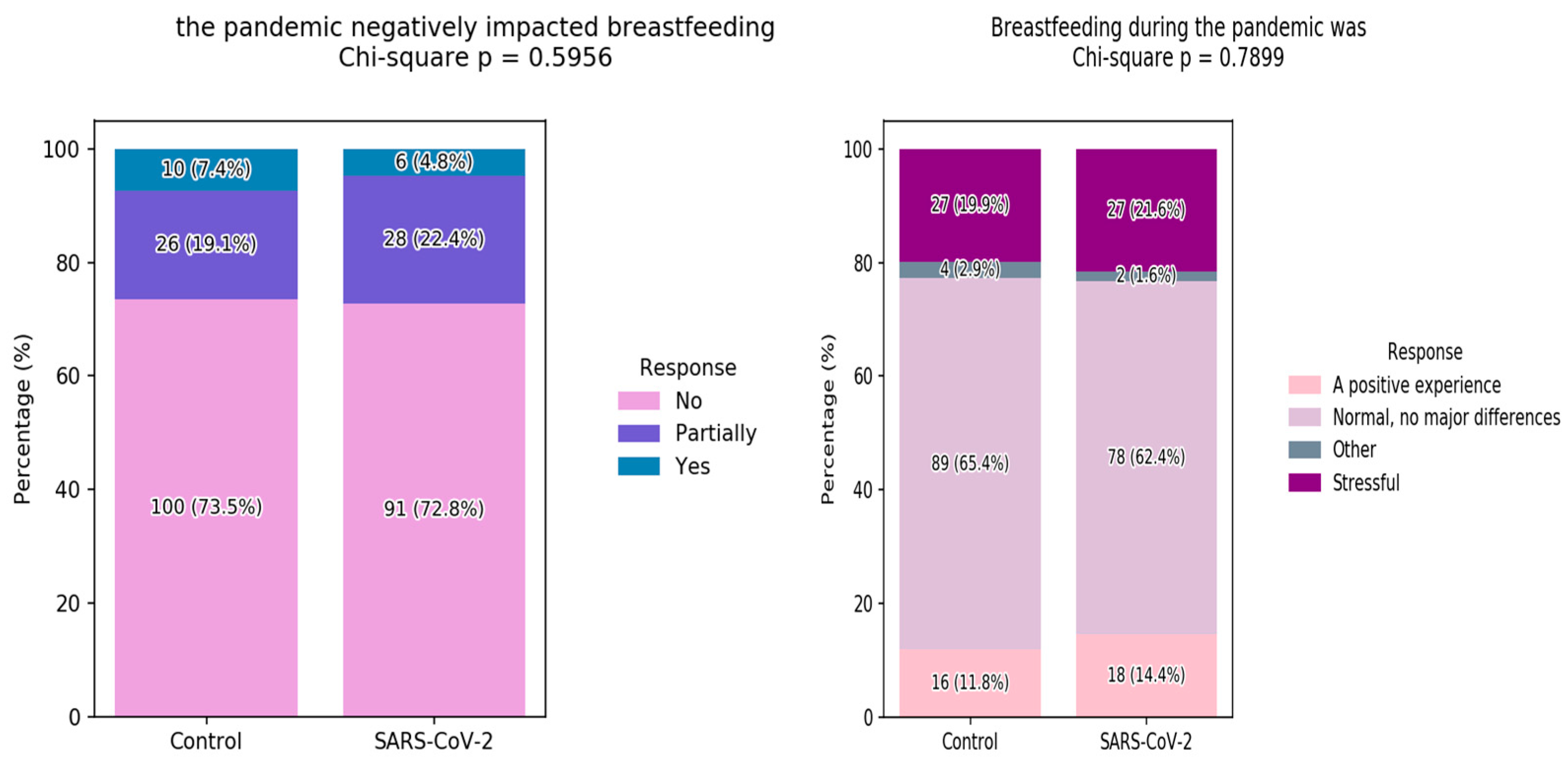

| Breastfeed during the Pandemic | ||||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (5.1%) | 7 (2.7%) | 0.0287 * |

| Breastfeeding and formula | 17 (13.6%) | 24 (17.6%) | 41 (15.7%) | 0.467 |

| Exclusively breastfed | 108 (86.4%) | 105 (77.2%) | 213 (81.6%) | 0.0792 |

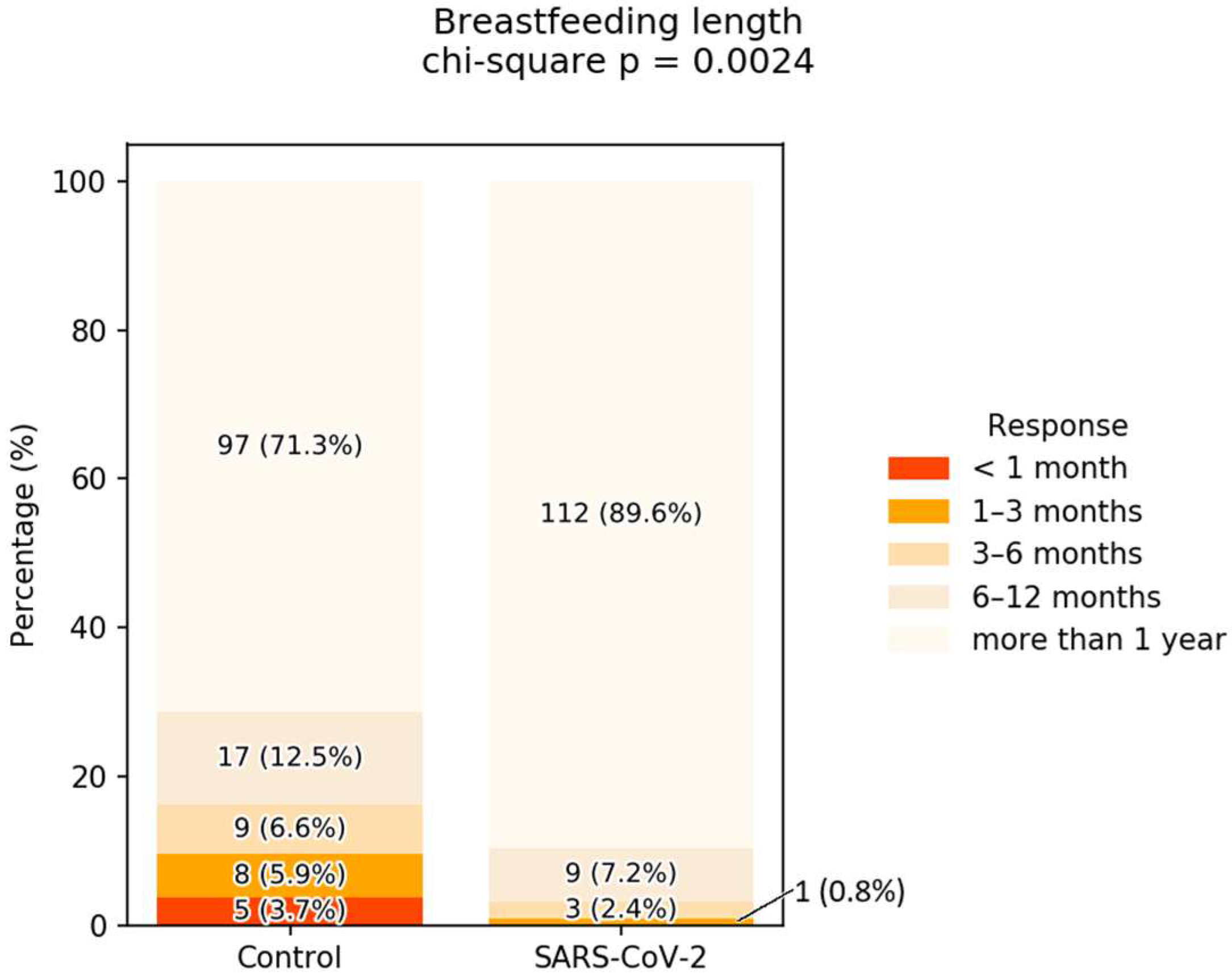

| Breastfeeding Duration | ||||

| <1 month | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (3.7%) | 5 (1.9%) | 0.0868 |

| 1–3 months | 1 (0.8%) | 8 (5.9%) | 9 (3.4%) | 0.0563 |

| 3–6 months | 3 (2.4%) | 9 (6.6%) | 12 (4.6%) | 0.1837 |

| 6–12 months | 9 (7.2%) | 17 (12.5%) | 26 (10.0%) | 0.2219 |

| more than 1 year | 112 (89.6%) | 97 (71.3%) | 209 (80.1%) | 0.0004 *** |

| Control | SARS-CoV-2 | All | Chi2_p_Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I was in a good state | 18/136 (13.2%) | 9/125 (7.2%) | 27/261 (10.3%) | 0.163 |

| Panic attacks | 14/136 (10.3%) | 16/125 (12.8%) | 30/261 (11.5%) | 0.660 |

| Low zest for life | 19/136 (14%) | 14/125 (11.2%) | 33/261 (12.6%) | 0.627 |

| Hopelessness about the future | 29/136 (21.3%) | 22/125 (17.6%) | 51/261 (19.5%) | 0.547 |

| Low energy | 29/136 (21.3%) | 26/125 (20.8%) | 55/261 (21.1%) | 0.961 |

| Unrealistic and excessive worries | 32/136 (23.5%) | 34/125 (27.2%) | 66/261 (25.3%) | 0.590 |

| Insomnia | 12/136 (8.8%) | 18/125 (14.4%) | 30/261 (11.5%) | 0.224 |

| I feared the possibility of my newborn or child becoming infected | 81/136 (59.6%) | 90/125 (72%) | 171/261 (65.5%) | 0.047 * |

| I feared for my life and my loved ones’ lives | 58/136 (42.6%) | 71/125 (56.8%) | 129/261 (49.4%) | 0.031 * |

| Panic related to the unknowns of the disease | 68/136 (50%) | 74/125 (59.2%) | 142/261 (54.4%) | 0.172 |

| Loneliness | 28/136 (20.6%) | 23/125 (18.4%) | 51/261 (19.5%) | 0.772 |

| Somatizations | 15/136 (11%) | 10/125 (8%) | 25/261 (9.6%) | 0.535 |

| Tendency to isolate | 42/136 (30.9%) | 47/125 (37.6%) | 89/261 (34.1%) | 0.311 |

| Tendency towards compulsive washing and disinfecting | 46/136 (33.8%) | 58/125 (46.4%) | 104/261 (39.8%) | 0.052 |

| Sadness | 31/136 (22.8%) | 23/125 (18.4%) | 54/261 (20.7%) | 0.470 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cigăran, R.-G.; Peltecu, G.; Botezatu, R.; Gică, N. The Experience of Breastfeeding Women During the Pandemic in Romania. Children 2025, 12, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101279

Cigăran R-G, Peltecu G, Botezatu R, Gică N. The Experience of Breastfeeding Women During the Pandemic in Romania. Children. 2025; 12(10):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101279

Chicago/Turabian StyleCigăran, Ruxandra-Gabriela, Gheorghe Peltecu, Radu Botezatu, and Nicolae Gică. 2025. "The Experience of Breastfeeding Women During the Pandemic in Romania" Children 12, no. 10: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101279

APA StyleCigăran, R.-G., Peltecu, G., Botezatu, R., & Gică, N. (2025). The Experience of Breastfeeding Women During the Pandemic in Romania. Children, 12(10), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101279