Leveraging User-Friendly Mobile Medical Devices to Facilitate Early Hospital Discharges in a Pediatric Setting: A Randomized Trial Study Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

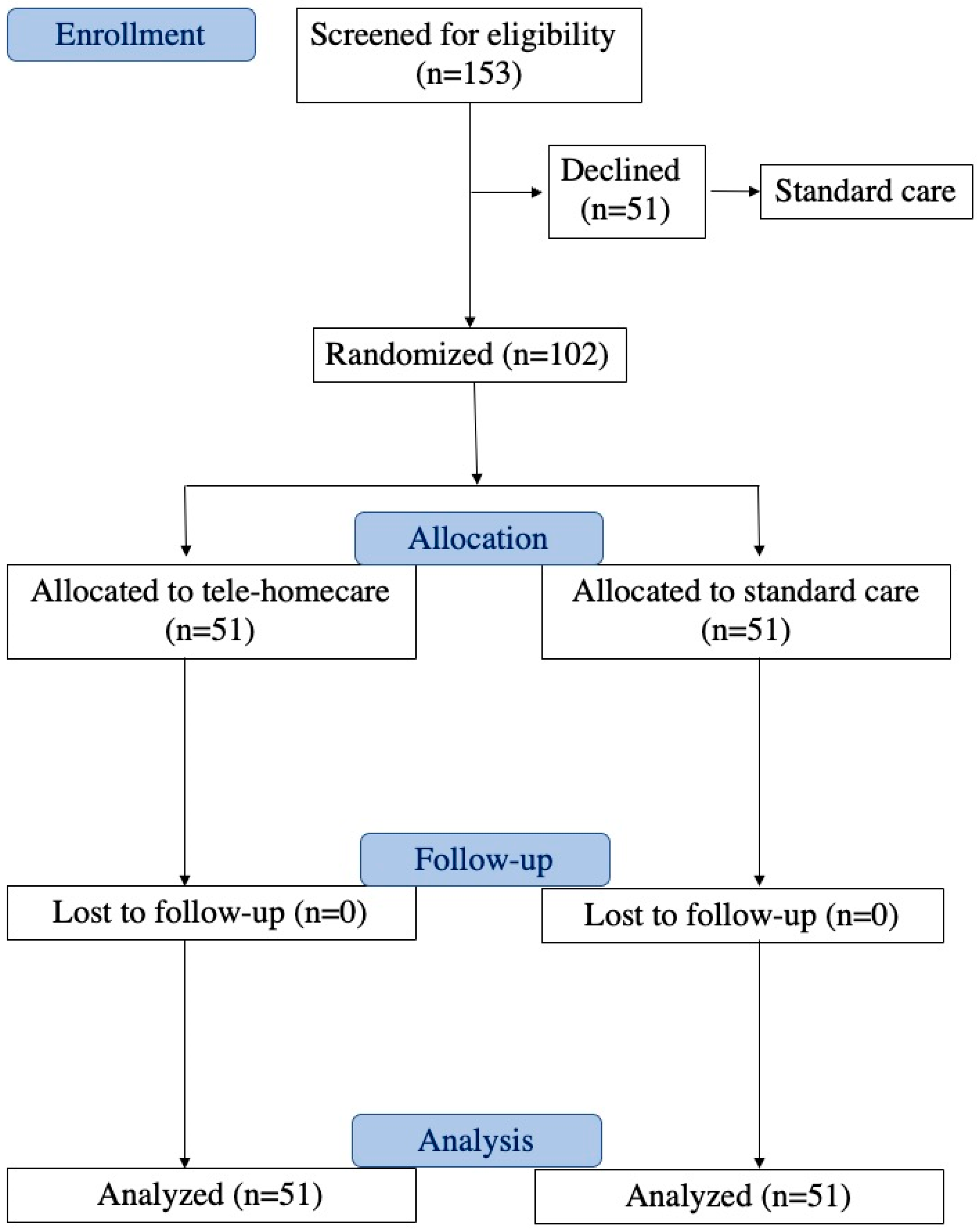

2.1. Study Design and Randomization

2.2. Participants

- Age of enrolled subjects: 0–18 years.

- Gender of patients (males and females).

- Patient status: hospitalized at the completion of treatment.

- Stability in vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation).

- Stability/improvement/resolution in biochemical tests.

- No fever.

- Consent/Assent: participants must be willing and provide appropriate consent or assent based on their age.

- Proximity to domicile: living within a maximum 45 min distance from the facility.

- Adequate home environment

- Language proficiency: adequate proficiency in the Italian language.

- Possession of a compatible device.

- Refusal to participate in the program.

- Instability in vital signs.

- Presence of fever.

- Deteriorating results in biochemical tests.

- Living more than 45 min away from the facility.

- Inadequate home facilities.

- Language barrier.

- Lack of possession of a compatible device.

- Not having a device with an operating system capable of supporting the Tytocare app 7.0.0.433.

2.3. Intervention

2.3.1. Experimental Group: Telehomecare

- -

- Stethoscope: Frequency range of 20–3500 Hz, heart rate range of 30–250 BPM, dimensions of 40 × 39 mm, and a weight of 0.06 kg.

- -

- Otoscope: Image resolution of 640 × 480 (VGA), weight of 0.02 kg, and an adaptable speculum for children (3 mm).

- -

- Tongue Depressor: For children (60 mm), weight of 0.011 kg.

- -

- Thermometer: Detection range of 34.4–42.2 °C; accuracy of 0.2 °C for the temperature range 38–41 °C, with a precision of 0.2 degrees Celsius within the range of 38 to 41 degrees Celsius and a precision of 0.3 degrees Celsius outside this range (compliant with ASTM E1965-98 [16] and ISO 80601-2-56 [17]).

2.3.2. Non-Intervention Group: Standard Care

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. User and Physician Survey Questions

- Sociodemographic information about the children and parents.

- Employment details of parents who work.

- Distance between home and the hospital.

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Randomized Telehomecare and Standard Care Groups

4.1.1. Clinical Outcomes

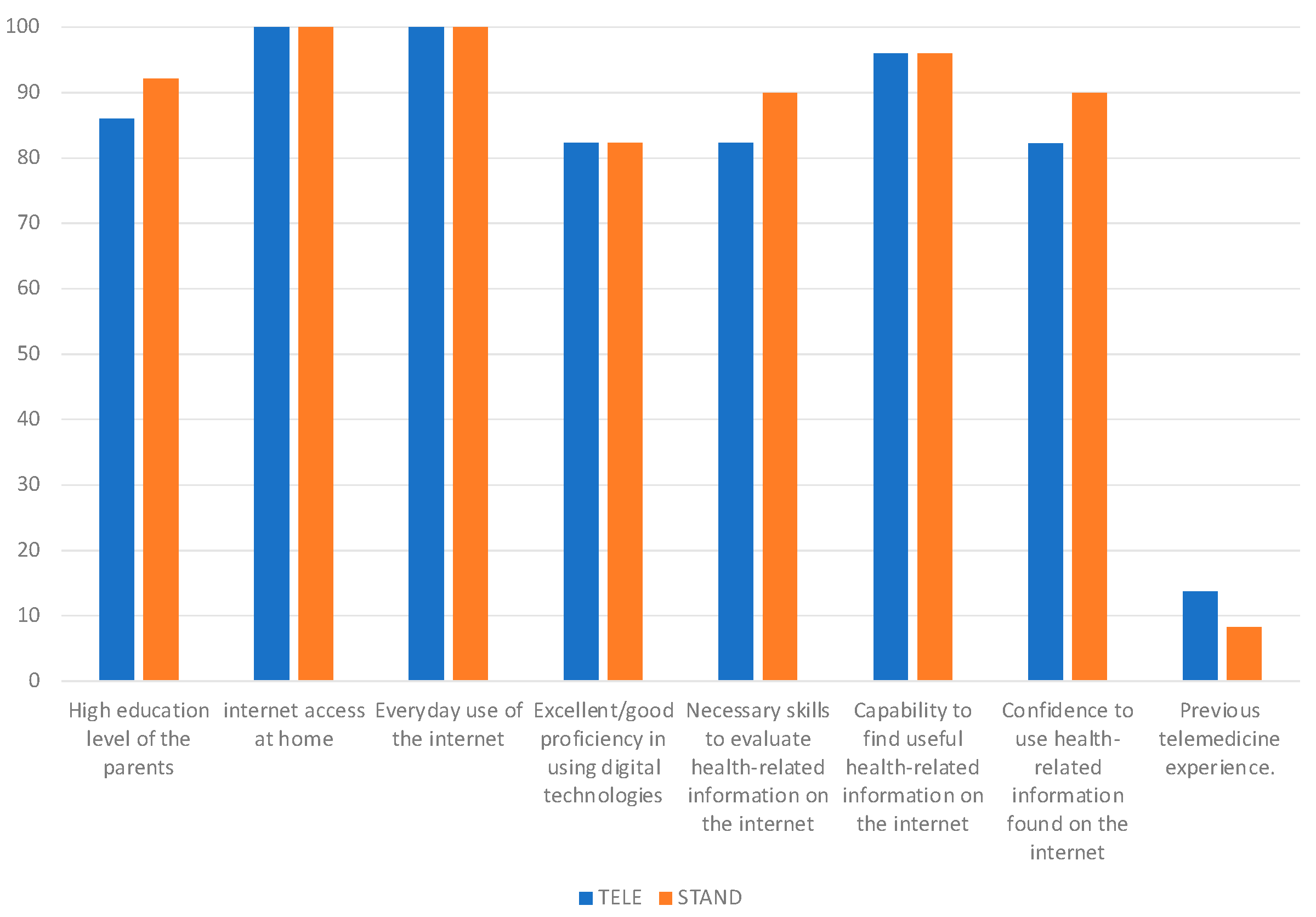

4.1.2. User Survey Results in Randomized Groups

4.2. No-Telemedicine Group

4.3. Patient Satisfaction Level of the Hospitalization Experience

4.4. Physician Survey Results

5. Discussion

6. Study Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bird, M.; Li, L.; Ouellette, C.; Hopkins, K.; McGillion, M.H.; Carter, N. Use of Synchronous Digital Health Technologies for the Care of Children with Special Health Care Needs and Their Families: Scoping Review. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2019, 2, e15106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Connected health. In How Digital Technology Is Transforming Health and Social Care; Deloitte: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gajarawala, S.N.; Pelkowski, J.N. Telehealth Benefits and Barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, W.; Zhou, K.; Waddell, E.; Myers, T.; Dorsey, E.R. Improving Access to Care: Telemedicine Across Medical Domains. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Medical 4.0 technologies for healthcare: Features, capabilities, and applications. Internet Things Cyber-Physical Syst. 2022, 2, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagala, S.G.; Gupta, V.; Kumawat, S.; Anamika, F.; McGillen, B.; Jain, R. Hospital at home: Emergence of a high-value model of care delivery. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 35, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillion, M.; Yost, J.; Turner, A.; Bender, D.; Scott, T.; Carroll, S.; Ritvo, P.; Peter, E.; Lamy, A.; Furze, G.; et al. Technology-Enabled Remote Monitoring and Self-Management—Vision for Patient Empowerment Following Cardiac and Vascular Surgery: User Testing and Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2016, 5, e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccotti, G.; Calcaterra, V.; Foppiani, A. Present and future of telemedicine for pediatric care: An Italian regional experience. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2023, 49, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarino, S.; Calcaterra, V.; Fini, G.; Foppiani, A.; Sanzo, A.; Pisarra, M.; Infante, G.; Marsilio, M.; Raso, I.; Santacesaria, S.; et al. A pediatric telecardiology system that facilitates integration between hospital-based services and community-based primary care. Int. J. Med Inform. 2024, 181, 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizio, A.; Fucarino, A.; Cantoia, M.; De Giorgio, A.; Garrido, N.D.; Iuliano, E.; Reis, V.M.; Sausa, M.; Vilaça-Alves, J.; Zimatore, G.; et al. Smart Devices for Health and Wellness Applied to Tele-Exercise: An Overview of New Trends and Technologies Such as IoT and AI. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskel, O.; Itelman, E.; Zilber, E.; Barkai, G.; Segal, G. Remote Auscultation of Heart and Lungs as an Acceptable Alternative to Legacy Measures in Quarantined COVID-19 Patients—Prospective Evaluation of 250 Examinations. Sensors 2022, 22, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Lima, T.C.; da Silva, M.R.T.; Rabha, A.C.P.; Ricieri, M.C.; Fachi, M.M.; Afonso, R.C.; Motta, F.A. Assessment of Pediatric Telemedicine Using Remote Physical Examinations with a Mobile Medical Device: A Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2252570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, N.L.; Novicoff, W.; Gunnell, B.; Gordon, D.C. Comparison of a Novel Handheld Telehealth Device with Stand-Alone Examination Tools in a Clinic Setting. Telemed. J. e-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2019, 25, 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notario, P.M.; Gentile, E.; Amidon, M.; Angst, D.; Lefaiver, C.; Webster, K. Home-Based Telemedicine for Children with Medical Complexity. Telemed. J. e-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2019, 25, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: http://www.aal-europe.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/vINCI-Call-2017-DIGITAL-SKILLS-QUESTIONNAIRE-END-USERS.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- ASTM E1965-98; Standard Specification for Infrared Thermometers for Intermittent Determination of Patient Temperature. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.astm.org/e1965-98r23.html (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- ISO 80601-2-56; Medical Electrical Equipment—Part 2-56: Particular Requirements for Basic Safety and Essential Performance of Clinical Thermometers for Body Temperature Measurement. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/75005.html (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Vuorikari, R.; Kluzer, S.; Punie, Y. DigComp 2.2: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens—With New Examples of Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes, EUR 31006 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-92-76-48882-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Del Giudice, P.; Poletto, M.; Battistella, C.; Conte, A.; De Odorico, A.; Lesa, L.; Menegazzi, G.; Brusaferro, S. Validazione Della Versione Italiana del Questionario di Alfabetizzazione Sanitaria Digitale (IT-eHEALS). Bollettino Epidemiologico Nazionale. 2018. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/ben/2018/luglio-agosto/2 (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Bonn, M. The effects of hospitalisation on children: A review. Curationis 1994, 17, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, G.L.L.; Fernandes, M.d.G.M.; da Nóbrega, M.M.L. Hospitalization anxiety in children: Conceptual analysis. Ansiedade da hospitalização em crianças: Análise conceitual. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2016, 69, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Jowf, G.I.; Ahmed, Z.T.; An, N.; Reijnders, R.A.; Ambrosino, E.; Rutten, B.P.F.; de Nijs, L.; Eijssen, L.M.T. A Public Health Perspective of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commodari, E. Children staying in hospital: A research on psychological stress of caregivers. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2010, 36, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.L.; Jerman, P.; Marques, S.S.; Koita, K.; Boparai, S.K.P.; Harris, N.B.; Bucci, M. Systematic review of pediatric health outcomes associated with childhood adversity. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyne, I. Children’s Experiences of Hospitalization. J. Child Health Care 2006, 10, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil, K.; Krueger, P. Patterns of family adaptation to childhood asthma. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2002, 17, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Improvement Team Scotland. Delayed Discharge. Available online: https://www.alliance-scotland.org.uk/blog/resources/joint-improvement-team-legacy-report/ (accessed on 14 March 2015).

- Vesterby, M.S.; Pedersen, P.U.; Laursen, M.; Mikkelsen, S.; Larsen, J.; Søballe, K.; Jørgensen, L.B. Telemedicine support shortens length of stay after fast-track hip replacement. Acta Orthop. 2017, 88, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, L.S.; O’Brien, K. The evolution of family-centered care: From supporting parent-delivered interventions to a model of family integrated care. Birth Defects Res. 2019, 111, 1044–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, P.M.; Pascual-Carrasco, M.; Hernandez, C.M.; de Molina, R.M.; Arvelo, L.A.; Cadavid, B.; Lopez, F.; Sanchez-Madariaga, R.; Sam, A.; Alonso, A.T.; et al. Follow-up with Telemedicine in Early Discharge for COPD Exacerbations: Randomized Clinical Trial (TELEMEDCOPD-Trial). COPD 2021, 18, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Naglie, G.; Cameron, J.I. Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, A.; Leahy-Warren, P.; Savage, E.; Hegarty, J.; Cornally, N.; Day, M.R.; Sahm, L.; O’connor, K.; O’doherty, J.; Liew, A.; et al. Interventions to Promote Early Discharge and Avoid Inappropriate Hospital (Re)Admission: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.-R.; Yeo, S.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, Y.-H.; Park, K.-H.; Roh, H. Medical education trends for future physicians in the era of advanced technology and artificial intelligence: An integrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2019, 19, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.; Lee, D.-R.D. Physician Satisfaction with Telehealth: A Systematic Review and Agenda for Future Research. Qual. Manag. Heal. Care 2022, 31, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell-Aldeghi, R.; Gibrat, B.; Rapp, T.; Chauvin, P.; Le Guern, M.; Billaudeau, N.; Ould-Kaci, K.; Sevilla-Dedieu, C. Determinants of the Cost-Effectiveness of Telemedicine: Systematic Screening and Quantitative Analysis of the Literature. Telemed. J. e-Health Off. J. Am. Telemed. Assoc. 2023, 29, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Telehomecare | Standard Care | No-Telemedicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the children and parents | |||

| Who is completing the questionnaire? | |||

| Mother | 84.31% | 94.12% | 86.27% |

| Father | 15.69% | 5.88% | 11.76% |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 1.96% |

| What is the age of the individual completing the questionnaire? | 35.70 ± 10.79 | 35.93 ± 7.81 | 38.08 ± 8.47 |

| What is the nationality of the individual completing the questionnaire? | |||

| Italian/Foreign | 72.6%/27.4% | 70.59%/29.41% | 82.35/17.65% |

| Does the patient have siblings? | |||

| Yes (1/more than 1) | 52% | 53.33% | 54.9% |

| (38%/14%) | (30.0%/16.67%) | (37.25%/17.4%) | |

| No | 48% | 53.33% | 45.1% |

| What is the parental educational background of the individual answering the questionnaire? | |||

| Middle school | 12.0% | 10.0% | 7.84% |

| High school | 46.0% | 40.0% | 52.94% |

| College and/or postgraduate | 42.0% | 50% | 39.21% |

| Employment characteristics of the working parents | |||

| Is the mother currently employed? | |||

| Yes, employed-full-time/part-time/independent contractor | 72.5% | 76.47% | 78.43% |

| No, not seeking work/unemployed and seeking work | 27.45% | 23.53% | 21.57% |

| Is the father currently employed? | |||

| Yes, employed-full-time/part-time/independent contractor | 97.877% | 100% | 96.08% |

| No, not seeking work/unemployed and seeking work | 2.13% | 0% | 3.92 |

| Distance from residence to hospital | |||

| How far is the hospital from your home (in kilometers)? | 26.25 ± 10.40 | 24.65 ± 16.65 | 25.81 ± 10.79 |

| What mode of transportation would you use to reach the hospital? | |||

| Public transport/Private vehicle | 16.33%/83.67% | 19.57%/80.43% | 8.7%/92.30% |

| Parental proficiency, mindset, and ability in utilizing technology, digital communication systems and telehealth services | |||

| How frequently do you: | |||

| Require assitance with reading medical documentation | |||

| 25.49%/33.33% | 16.67%/23.33% | 11.76%/21.57% |

| 29.41% | 46.67% | 45.10% |

| 9.8%/1.96% | 13.33%/0% | 19.61%/1.96 |

| Experience challenges in comprehending health status because of reading limitations | |||

| 27.45%/37.25% | 16.67%/30% | 17.65%/21.57% |

| 27.45% | 43.33% | 50.98% |

| 4%/0% | 6.67%/3.33% | 9.80% |

| Encounter difficulties in comprehending health-related information | |||

| 39.22%/37.25% | 23.33%/33.33% | 25.49%/37.25% |

| 19.61% | 40.0% | 29.41% |

| 3.92%/0% | 0%/3.33% | 7.84% |

| Feel confident in filling out medical consent forms | |||

| 20.0%/16.0% | 10.0%/6.67% | 11.76%/21.57% |

| 20% | 30% | 45.10% |

| 36%/8% | 30%/23.33% | 19.6%/1.96% |

| Do you have internet access at your home? | |||

| Yes/No | 94.12%/5.88% | 93.33%/6.67% | 89.90%/10.20% |

| How frequently do you utilize your home internet connection? | |||

| Every day | 100% | 100% | 97.56% |

| One/two times a week | 0% | 0% | 2.44% |

| Occasionally | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| What do you primarily use your smartphone for? | |||

| Phone calls | 94.11% | 94.12% | 94.11% |

| Messages | 92.16% | 902% | 88.23% |

| Shopping | 72.55% | 82.36 | 68.62% |

| Banking | 76.47% | 74.5% | 64.71% |

| Sending emails | 90.20% | 86.28 | 74.51% |

| Learning | 52.94% | 54.90% | 47.06% |

| Social network use | 72.55% | 58.8% | 66.66% |

| Entertainment (games/movies) | 62.74% | 62.74% | 49.01% |

| Checking health status | 39.21% | 43.14 | 68.63% |

| How would you rate your proficiency in using digital technologies? | |||

| Excellent/Good | 82.35% | 82.35% | 78% |

| Moderate | 17.65% | 17.65% | 20% |

| Inadequate | 0% | 0% | 2% |

| Utilization of applications or online platforms for: | |||

| 80.97% | 80.39% | 84.31% |

| 80.39% | 80.39% | 78.43% |

| 82.35% | 82.35% | 70.58% |

| 80.39% | 80.39% | 68.63% |

| 74.51% | 74.50% | 82.35% |

| 74.51% | 74.50% | 74.51% |

| 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.02% |

| I possess the ability to locate valuable health-related content online | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 96.08% | 96% | 98% |

| Disapprove | 3.92% | 4% | 2% |

| I am proficient in assessing health-related information obtained from the internet | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 82.35% | 90% | 86% |

| Disapprove | 17.65% | 10% | 14% |

| I am comfortable utilizing health-related information sourced from the internet. | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 86.27% | 90% | 80% |

| Disapprove | 13.73% | 10% | 20% |

| I began utilizing the internet to seek health-related information only following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 52% | 41% | 46% |

| Disapprove | 48% | 59% | 54% |

| Tele-visit | |||

| Did you know the definition of “Tele-visit” prior to today? | |||

| Yes | 45.10% | 20% | 50.98% |

| No | 54.90% | 78% | 47.06% |

| I thought it was something different | 0% | 2% | 1.96% |

| Have you ever used a telemedicine service in the past? | |||

| Yes/No | 13.73%/86.27% | 8.33%/91.67% | 6%/94% |

| If Yes, regarding your previous experiences with telemedicine, what is your level of satisfaction? | |||

| Very satisfied/Satisfied/Partially satisfied | 100% | 96% | 95.45% |

| Not at all satisfied | 0% | 4% | 4.55% |

| Question | Telehomecare | Standard Care |

|---|---|---|

| Disadvantages and limits | ||

| Because I believe that you don’t establish a personal relationship with the doctor | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 82.0% | 85.59% |

| Disapprove | 18.0% | 14.41% |

| Because I believe that it is not possible to ask the doctor all the questions | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 75.51% | 82.14% |

| Disapprove | 24.49% | 17.86% |

| The proposed technological tools are too difficult to use | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 78.43% | 77.78% |

| Disapprove | 21.57% | 22.22% |

| I think a tele-visit is NOT as reliable as a real visit | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 86.27% | 92.86% |

| Disapprove | 13.73% | 7.14% |

| I think I might have connection problems | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 66.7% | 50% |

| Disapprove | 33.3% | 50% |

| I’m not familiar enough with technology in general | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 68.63% | 60.71% |

| Disapprove | 31.37% | 39.29% |

| I would still need someone’s help during the visit (for connection, to hold the baby, etc.) and it’s not guaranteed that they will be available | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 68.63% | 67.86% |

| Disapprove | 31.37% | 32.14% |

| I fear there may be privacy issues | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 54.9% | 64.29% |

| Disapprove | 45.10% | 35.71% |

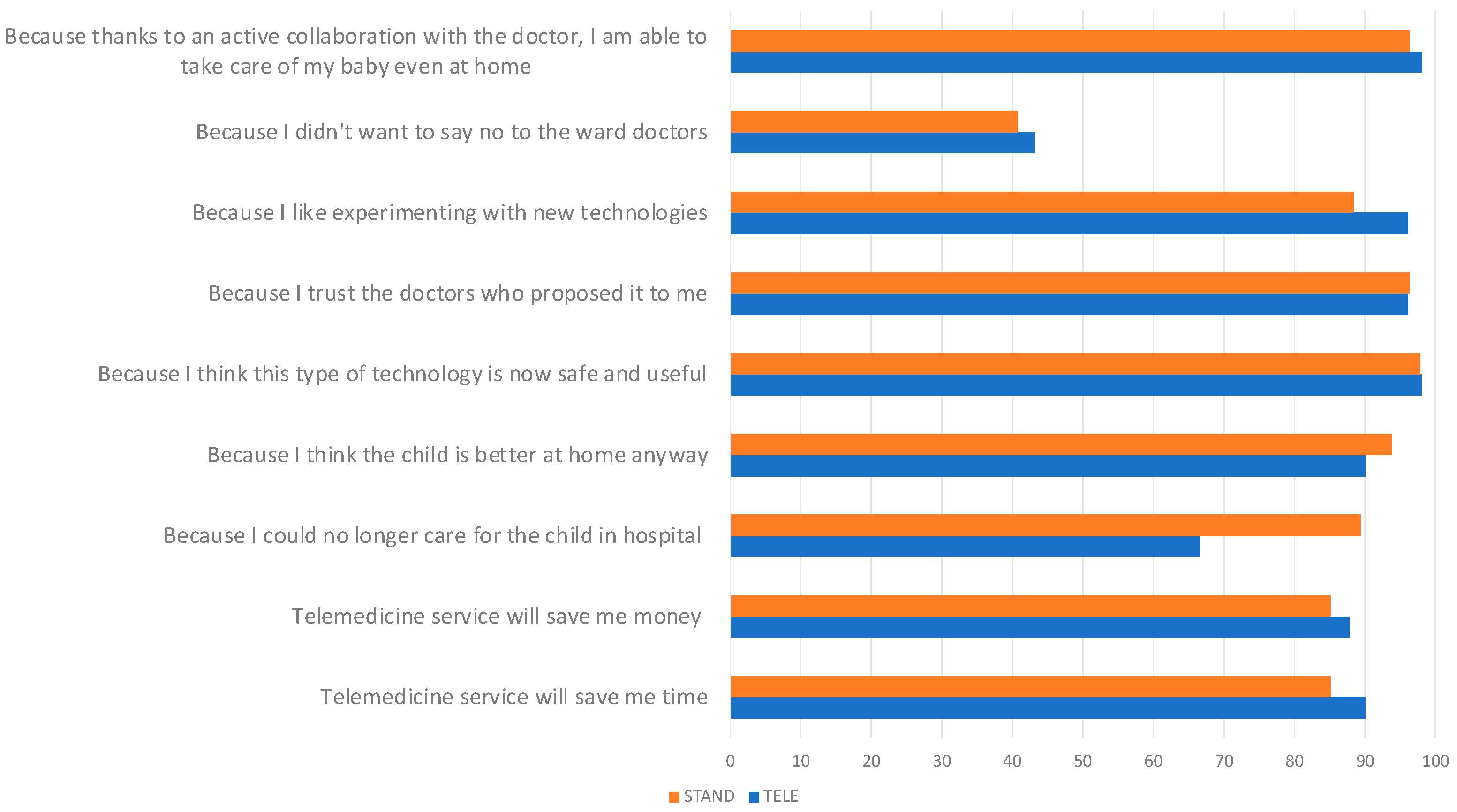

| Main reason why you decided to make yourself available to adopt the telemedicine service for your child’s discharge | ||

| It will save me time | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 90.0% | 85.11% |

| Disapprove | 10.0% | 14.89% |

| It will save me money (travel, permits, etc.) | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 87.76% | 85.11% |

| Disapprove | 12.24% | 14.89% |

| Because I could no longer care for the child in hospital (due to work, caring for other children, etc.) | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 66.7% | 89.36% |

| Disapprove | 33.33% | 10.64% |

| Because I think the child is better at home anyway | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 90.0% | 93.75% |

| Disapprove | 10% | 6.25% |

| Because I think this type of technology is now safe and useful | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 98.0% | 97.87% |

| Disapprove | 2.0% | 2.13% |

| Because I trust the doctors who proposed it to me | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 96.08% | 96.3% |

| Disapprove | 3.92% | 3.7% |

| Because I like experimenting with new technologies | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 96.08% | 88.4% |

| Disapprove | 3.92% | 11.54% |

| Because I didn’t want to say no to the ward doctors | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 43.14% | 40.74% |

| Disapprove | 56.86% | 59.26% |

| Because thanks to an active collaboration with the doctor, I am able to take care of my baby even at home | ||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 98.04% | 96.3% |

| Disapprove | 1.96% | 3.70% |

| Questions | Telehomecare |

|---|---|

| The information received upon discharge was clear regarding: | |

| Operation of Tytocare device | |

| No, not at all | 2.13% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 6.38% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 91.49% |

| Who would have contacted her | |

| No, not at all | 2.13% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 6.38% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 91.49% |

| When he would contact her | |

| No, not at all | 2.13% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 0% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 97.87% |

| How Tytocare should have been used | |

| No, not at all | 4.26% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 8.51% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 91.49% |

| How he should have followed the therapy | |

| No, not at all | 8.51% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 4.26% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 87.24% |

| What to do if the child gets worse | |

| No, not at all | 8.89% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 4.44% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 86.66% |

| Who to contact in case of need | |

| No, not at all | 2.17% |

| Yes, but not as clear | 8.70% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 89.13% |

| Satisfaction in using telemedicine | |

| How satisfied are you overall with the telehomecare you received? | |

| No, not at all | 0% |

| Yes/Yes how much | 100% |

| During telehomecare the doctors who treated the child were very scrupulous and caring | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 96% |

| Disapprove | 4% |

| The doctor made me feel safe while continuing the therapy at home with tele-visits | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 100% |

| Disapprove | 0% |

| The doctor made the experience during the tele-visits pleasant | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 97.92% |

| Disapprove | 2.08% |

| I felt comfortable communicating with the professional using the telemedicine system | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 97.87% |

| Disapprove | 2.13% |

| I was able to describe my child’s health condition during televisit | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 97.87% |

| Disapprove | 2.13% |

| I managed to collect and share the required parameters with the doctor | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 100% |

| Disapprove | 0% |

| I followed all the instructions I was given on what to do once I got home | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 100% |

| Disapprove | 0% |

| I had no technical problems during the tele-visit (e.g., connection, hearing, seeing) | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 100% |

| Disapprove | 0% |

| How do you rate the telemedicine experience? | |

| Poor/Fair | 0% |

| Good/very good | 100% |

| In light of your experience with Tytocare, if you were asked to use the Tytocare telemedicine device in the future, do you think you would still be willing to evaluate its use? | |

| No/More no that yes | 6.25% |

| Yes/More yes that no | 93.75% |

| Question | No Telemedicine |

|---|---|

| Main reason why you decided NOT to make yourself available to adopt the Tytocare device for your child’s discharge | |

| Because I believe that you don’t establish a personal relationship with the doctor | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 95.45% |

| Disapprove | 4.55% |

| Because I believe that it is not possible to ask the medical doctor all the questions | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 93.18% |

| Disapprove | 6.82% |

| The proposed technological tools are too difficult to use | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 84.09% |

| Disapprove | 15.91% |

| I think a tele-visit is NOT as reliable as a real visit | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 97.73% |

| Disapprove | 2.27% |

| I think I might have connection problems | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 68.18% |

| Disapprove | 31.82% |

| I’m not familiar enough with technology in general | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 62.22% |

| Disapprove | 37.78% |

| I would still need someone’s help during the visit (for connection, to hold the baby, etc.) and it’s not guaranteed that they will be available | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 69.57% |

| Disapprove | 30.43% |

| I fear there may be privacy issues | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 68.89% |

| Disapprove | 31.11% |

| Because I don’t trust technologies | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 65.22% |

| Disapprove | 34.78% |

| I think that only in hospital does my son receive the best care | |

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 97.83% |

| Disapprove | 2.17% |

| Parent’s willingness to use the device in the future | |

| No/More no that yes | 59.18% |

| Yes/More yes that no | 40.82% |

| Question | Telehomecare | Standard Care | No Telemedicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| The doctors who treated the child were very thorough and caring | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 96% | 100% | 100% |

| Disapprove | 4% | 0% | 0% |

| The doctors attending to the child were exceptionally meticulous and compassionate | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Disapprove | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| The parent believes that the child can only receive the best care in a hospital | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | Not considered | 53.33% | 50.98% |

| Disapprove | 46.67% | 49.02% | |

| At times, the doctor treating the child did not pay attention to what the child or the caregiver was attempting to communicate | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 32% | 40%% | 50.98% |

| Disapprove | 68% | 60%% | 49.02% |

| The parent believes that the doctor was not as competent as they should have been. | |||

| Fully agree/Agree/Tend to agree | 90% | 100% | 90% |

| Disapprove | 10% | 0% | 10% |

| The parent is satisfied with the care received | |||

| No | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Yes | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Would you recommend this department to other patients? | |||

| No/More no that yes | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Yes/More yes that no | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Would you still choose this department for treatment? | |||

| No/More no that yes | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Yes/More yes that no | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| How would you rate the care you received? | |||

| Poor/Fair | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Good/very good | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Questions | Response % |

|---|---|

| How satisfied are you overall with the Tytocare process with patients? | |

| 0% |

| 3.85% |

| 21.15% |

| 75% |

| How many adults were present during the televisit? | |

| 65.22% |

| 34.78% |

| How well were the parents able to follow all the instructions provided for home care? | |

| 0% |

| 5.77% |

| 9.62% |

| 84.62% |

| Did the parents adhere to the agreed-upon time for the televisit?” | |

| 0% |

| 1.92% |

| 11.54% |

| 86.54% |

| Were there any technical problems during the tele-visit? | |

| 42.31% |

| 15.38% |

| 21.15% |

| 21.15% |

| How successful was the parent in collecting and sharing the required information and parameters? | |

| 1.92% |

| 3.85% |

| 23.08% |

| 71.15% |

| How comfortable did you feel communicating with your parent using the telemedicine system? | |

| 0% |

| 23.08% |

| 76.92% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zuccotti, G.; Marsilio, M.; Fiori, L.; Erba, P.; Destro, F.; Zamana, C.; Folgori, L.; Mandelli, A.; Braghieri, D.; Guglielmetti, C.; et al. Leveraging User-Friendly Mobile Medical Devices to Facilitate Early Hospital Discharges in a Pediatric Setting: A Randomized Trial Study Protocol. Children 2024, 11, 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060683

Zuccotti G, Marsilio M, Fiori L, Erba P, Destro F, Zamana C, Folgori L, Mandelli A, Braghieri D, Guglielmetti C, et al. Leveraging User-Friendly Mobile Medical Devices to Facilitate Early Hospital Discharges in a Pediatric Setting: A Randomized Trial Study Protocol. Children. 2024; 11(6):683. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060683

Chicago/Turabian StyleZuccotti, Gianvincenzo, Marta Marsilio, Laura Fiori, Paola Erba, Francesca Destro, Costantino Zamana, Laura Folgori, Anna Mandelli, Davide Braghieri, Chiara Guglielmetti, and et al. 2024. "Leveraging User-Friendly Mobile Medical Devices to Facilitate Early Hospital Discharges in a Pediatric Setting: A Randomized Trial Study Protocol" Children 11, no. 6: 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060683

APA StyleZuccotti, G., Marsilio, M., Fiori, L., Erba, P., Destro, F., Zamana, C., Folgori, L., Mandelli, A., Braghieri, D., Guglielmetti, C., Pisarra, M., Magnani, L., Infante, G., Dilillo, D., Fabiano, V., Carlucci, P., Zoia, E., Pelizzo, G., & Calcaterra, V. (2024). Leveraging User-Friendly Mobile Medical Devices to Facilitate Early Hospital Discharges in a Pediatric Setting: A Randomized Trial Study Protocol. Children, 11(6), 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060683