Effectiveness of Learning through Play Plus (LTP Plus) Parenting Intervention on Behaviours of Young Children of Depressed Mothers: A Randomised Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Settings

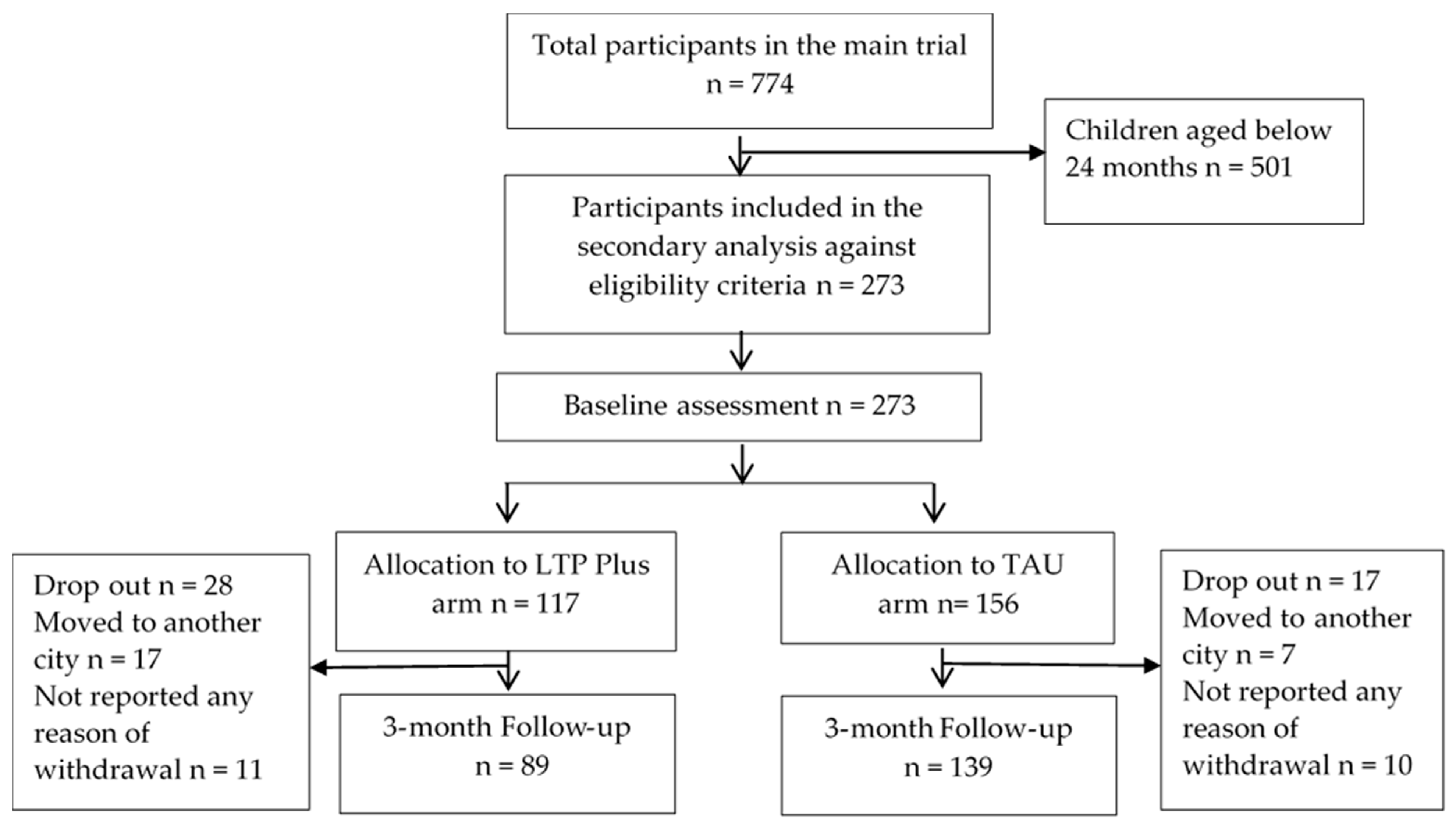

2.2. Recruitment and Randomisation

2.3. The Intervention: Learning through Play Plus (LTP Plus)

2.4. Treatment as Usual (TAU)

2.5. Outcome Assessment

2.5.1. Child Outcomes

The Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) [30]

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) [31]

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Child Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alenko, A.; Girma, S.; Abera, M.; Workicho, A. Children emotional and behavioural problems and its association with maternal depression in Jimma town, southwest Ethiopia. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietikainen, J.T.; Kiviruusu, O.; Kylliainen, A.; Polkki, P.; Saarenpaa-Heikkila, O.; Paunio, T.; Paavonen, E.J. Maternal and paternal depressive symptoms and children’s emotional problems at the age of 2 and 5 years: A longitudinal study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dachew, B.A.; Heron, J.E.; Alati, R. Parental depressive symptoms across the first three years of a child’s life and emotional and behavioural problem trajectories in children and adolescents. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 159, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/promotion-prevention/maternal-mental-health#:~:text=Worldwide%20about%2010%25%20of%20pregnant,a%20mental%20disorder%2C%20primarily%20depression (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Atif, M.; Halaki, M.; Raynes-Greenow, C.; Chow, C. Perinatal depression in Pakistan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Birth 2021, 48, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trussell, T.M.; Ward, W.L.; Conners Edge, N.A. The impact of maternal depression on children: A call for maternal depression screening. Clin. Pediatr. 2018, 57, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachter, L.M.; Auinger, P.; Palmer, R.; Weitzman, M. Do parenting and the home environment, maternal depression, neighborhood, and chronic poverty affect child behavioral problems differently in different racial-ethnic groups? Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.; Dobson, R.; Maddison, R. The relationship between household chaos and child, parent, and family outcomes: A systematic scoping review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, J.E.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Rasheed, M.; Obradović, J. Measuring and understanding social-emotional behaviors in preschoolers from rural Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netsi, E.; Pearson, R.M.; Murray, L.; Cooper, P.; Craske, M.G.; Stein, A. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveed, S.; Waqas, A.; Shah, Z.; Ahmad, W.; Wasim, M.; Rasheed, J.; Afzaal, T. Trends in bullying and emotional and behavioral difficulties among Pakistani schoolchildren: A cross-sectional survey of seven cities. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 448725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundele, M.O. Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2018, 7, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboud, F.E.; Yousafzai, A.K. Global health and development in early childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudfeld, C.R.; Mccoy, D.C.; Danaei, G.; Fink, G.; Ezzati, M.; Andrews, K.G.; Fawzi, W.W. Linear growth and child development in low-and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e1266–e1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousafzai, A.K.; Obradović, J.; Rasheed, M.A.; Rizvi, A.; Portilla, X.A.; Tirado-Strayer, N.; Siyal, S.; Memon, U. Effects of responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions on children’s development and growth at age 4 years in a disadvantaged population in Pakistan: A longitudinal follow-up of a cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e548–e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ssewanyana, D.; Martin, M.-C.; Lye, S.; Moran, G.; Abubakar, A.; Marfo, K.; Marangu, J.; Proulx, K.; Malti, T. Supporting child development through parenting interventions in low-to middle-income countries: An updated systematic review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 671988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, D.C.; Peet, E.D.; Ezzati, M.; Danaei, G.; Black, M.M.; Sudfeld, C.R.; Fawzi, W.; Fink, G. Early childhood developmental status in low-and middle-income countries: National, regional, and global prevalence estimates using predictive modeling. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, B.; Avan, B.I. Behavioral problems in preadolescence: Does gender matter? PsyCh J. 2020, 9, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prime, H.; Andrews, K.; Markwell, A.; Gonzalez, A.; Janus, M.; Tricco, A.C.; Bennett, T.; Atkinson, L. Positive parenting and early childhood cognition: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 26, 362–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitadze, I.; Lalayants, M. Mechanisms that mitigate the effects of child poverty and improve children’s cognitive and social–emotional development: A systematic review. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2021, 26, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Luchters, S.; Fisher, J. Early childhood development: Impact of national human development, family poverty, parenting practices and access to early childhood education. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britto, P.R.; Lye, S.J.; Proulx, K.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Matthews, S.G.; Vaivada, T.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Rao, N.; Ip, P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; et al. Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2017, 389, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, B.R.; Sikander, S.; Roy, R.; Soremekun, S.; Bhopal, S.S.; Avan, B.; Lingam, R.; Gram, L.; Amenga-Etego, S.; Khan, B.; et al. Effect of the SPRING home visits intervention on early child development and growth in rural India and Pakistan: Parallel cluster randomised controlled trials. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1155763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, F.; Leijten, P.; Melendez-Torres, G.; Landau, S.; Harris, V.; Mann, J.; Beecham, J.; Hutchings, J.; Scott, S. The earlier the better? Individual participant data and traditional meta-analysis of age effects of parenting interventions. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, N.; Kiran, T.; Fatima, B.; Chaudhry, I.B.; Husain, M.; Shah, S.; Bassett, P.; Cohen, N.; Jafri, F.; Naeem, S.; et al. An integrated parenting intervention for maternal depression and child development in a low-resource setting: Cluster randomized controlled trial. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, N.; Kiran, T.; Shah, S.; Rahman, A.; Raza-Ur-Rehman, R.U.; Saeed, Q.; Naeem, S.; Bassett, P.; Husain, M.; Haq, S.U.; et al. Efficacy of learning through play plus intervention to reduce maternal depression in women with malnourished children: A randomized controlled trial from Pakistan(✰). J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 278, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingebach, T.; Kamp-Becker, I.; Christiansen, H.; Weber, L. Meta-meta-analysis on the effectiveness of parent-based interventions for the treatment of child externalizing behavior problems. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, N.; Zulqernain, F.; Carter, L.-A.; Chaudhry, I.B.; Fatima, B.; Kiran, T.; Chaudhry, N.; Naeem, S.; Jafri, F.; Lunat, F.; et al. Treatment of maternal depression in urban slums of Karachi, Pakistan: A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an integrated maternal psychological and early child development intervention. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 29, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Malik, A.; Sikander, S.; Roberts, C.; Creed, F. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyberg, S.M.; Ross, A.W. Assessment of child behavior problems: The validation of a new inventory. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1978, 7, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, B.M.; Bradley, R.H. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment; University of Arkansas at Little Rock Little Rock: Fayetteville, AR, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B.M.; Bradley, R.H. Home Inventory Administration Manual; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences: Rock, AR, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Iqbal, Z.; Waheed, W.; Hussain, N. Translation and cultural adaptation of health questionnaires. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2003, 53, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens, K.Y.; Haltigan, J.D.; Bahm, N.I.G. Infant attachment, adult attachment, and maternal sensitivity: Revisiting the intergenerational transmission gap. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2016, 18, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonnenmacher, N.; Noe, D.; Ehrenthal, J.C.; Reck, C. Postpartum bonding: The impact of maternal depression and adult attachment style. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2016, 19, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, H.; Flykt, M.; Sinervä, E.; Nolvi, S.; Kataja, E.L.; Pelto, J.; Karlsson, H.; Karlsson, L.; Korja, R. How maternal pre-and postnatal symptoms of depression and anxiety affect early mother-infant interaction? J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 257, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.; Halligan, S.; Cooper, P. Postnatal depression and young children’s development. Handb. Infant Ment. Health 2018, 4, 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, A.; Pearson, R.M.; Goodman, S.H.; Rapa, E.; Rahman, A.; McCallum, M.; Howard, L.M.; Pariante, C.M. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014, 384, 1800–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, J.; Fößel, J.M.; Vierhaus, M.; Sann, A.; Eickhorst, A.; Zimmermann, P.; Spangler, G. Family risk and early attachment development: The differential role of parental sensitivity. Infant Ment. Health J. 2022, 43, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.H.; Rouse, M.H.; Connell, A.M.; Broth, M.R.; Hall, C.M.; Heyward, D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, E.; Sörensen, F.; Kallak, T.K.; Ramklint, M.; Eckerdal, P.; Heimgärtner, M.; Krägeloh-Mann, I.; Skalkidou, A. Maternal perinatal depressive symptoms trajectories and impact on toddler behavior–the importance of symptom duration and maternal bonding. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 273, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.R.; Kirby, J.N.; Tellegen, C.L.; Day, J.J. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M.R.; Kirby, J.N. A public-health approach to improving parenting and promoting children’s well-being. Child Dev. Perspect. 2014, 8, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, S.W. The polyvagal perspective. Biol. Psychol. 2007, 74, 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Farrelly, C.; Watt, H.; Babalis, D.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Barker, B.; Byford, S.; Ganguli, P.; Grimas, E.; Iles, J.; Mattock, H.; et al. A Brief Home-Based Parenting Intervention to Reduce Behavior Problems in Young Children: A Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboud, F.E.; Akhter, S. A cluster-randomized evaluation of a responsive stimulation and feeding intervention in Bangladesh. Pediatrics 2011, 127, e1191–e1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousafzai, A.K.; Rasheed, M.A.; Rizvi, A.; Armstrong, R.; Bhutta, Z.A. Effect of integrated responsive stimulation and nutrition interventions in the Lady Health Worker programme in Pakistan on child development, growth, and health outcomes: A cluster-randomised factorial effectiveness trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanes, L.D.; Hadaya, L.; Kanel, D.; Falconer, S.; Ball, G.; Batalle, D.; Counsell, S.J.; Edwards, A.D.; Nosarti, C. Associations Between Neonatal Brain Structure, the Home Environment, and Childhood Outcomes Following Very Preterm Birth. Biol. Psychiatry Glob. Open Sci. 2021, 1, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, D.; Poniman, C.; Filus, A.; Sumargi, A.; Boediman, L. Parenting style, child emotion regulation and behavioral problems: The moderating role of cultural values in Australia and Indonesia. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2020, 56, 320–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajal, N.J.; Paley, B. Parental emotion and emotion regulation: A critical target of study for research and intervention to promote child emotion socialization. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecil, C.A.M.; Barker, E.D.; Jaffee, S.R.; Viding, E. Association between maladaptive parenting and child self-control over time: Cross-lagged study using a monozygotic twin difference design. Br. J. Psychiatry 2012, 201, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Belsky, D.; Dickson, N.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Ross, S.; et al. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2693–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, R.; Katsura, T. Role of Parenting Style in Children’s Behavioral Problems through the Transition from Preschool to Elementary School According to Gender in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| TAU | Intervention | Total (n = 273) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) and Median [IQR] | |||

| Age mean (SD) | 28.76 (4.97) | 28.69 (5.73) | 28.20 (5.60) |

| No. of family members | 7 [6–10] | 7 [5–11] | 8 [6–12] |

| No. of children | 3 [2–5] | 3 [2–5] | 3 [2–4] |

| Total monthly income | 8000 [5000–12,000] | 9000 [6000–12,000] | 9000 [6000–15,000] |

| No. of rooms | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–2] | 1 [1–2] |

| n (%) | |||

| Education * | |||

| Uneducated | 79 (67.5%) | 88 (56.4%) | 167 (61.2%) |

| Up to primary | 24 (20.5%) | 41 (26.3%) | 65 (23.8%) |

| Middle/matriculation | 10 (8.5%) | 21 (13.5%) | 31 (11.4%) |

| Intermediate | 4 (3.4%) | 6 (3.8%) | 10 (3.7%) |

| Family system | |||

| Nuclear | 66 (56.4%) | 86 (55.1%) | 152 (55.7%) |

| Joint ** | 51 (43.6%) | 70 (44.9%) | 121 (44.3%) |

| Status of house | |||

| Ownership | 106 (90.6%) | 143 (91.7%) | 249 (91.2%) |

| Rental | 11 (9.4%) | 13 (8.3%) | 24 (8.8%) |

| n | TAU Mean (SD) | n | Intervention Mean (SD) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | ES | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECBI * | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 17.91 (12.41) | 156 | 16.35 (11.52) | 1.56 (−1.31 to 4.43) | 0.130 | 0.285 |

| 3rd month FU * | 89 | 18.02 (11.90) | 139 | 13.89 (11.77) | 4.13 (0.97 to 7.29) | 0.349 | <0.011 |

| Responsivity (HOME *) | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 7.54 (3.02) | 156 | 7.46 (3.06) | 0.08 (−0.66 to 0.81) | 0.026 | 0.836 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 7.73 (2.77) | 156 | 9.55 (1.85) | −1.82 (−2.40 to −1.23) | 0.747 | <0.001 |

| Acceptance (HOME) | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 3.50 (1.98) | 156 | 3.66 (1.99) | −0.16 (−0.64 to 0.31) | 0.081 | 0.499 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 3.77 (2.32) | 156 | 5.40 (1.67) | −1.63 (−2.13 to −1.13) | 0.806 | <0.001 |

| Organization (HOME) | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 3.65 (1.63) | 156 | 3.59 (1.61) | 0.06 (−0.33 to 0.45) | 0.037 | 0.762 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 3.83 (1.66) | 156 | 4.74 (1.23) | −0.91 (−1.28 to −0.56) | 0.623 | <0.001 |

| Learning material (HOME) | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 1.92 (2.25) | 156 | 1.98 (2.28) | −0.06 (−0.60 to 0.49) | 0.026 | 0.835 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 1.95 (2.28) | 156 | 3.65 (2.45) | −1.70 (−2.28 to −1.13) | 0.718 | <0.001 |

| Involvement (HOME) | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 2.76 (1.87) | 156 | 3.02 (1.74) | −0.26 (−0.69 to −0.17) | 0.144 | 0.240 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 3.64 (1.98) | 156 | 4.74 (1.72) | −1.10 (−1.56 to −0.65) | 0.593 | <0.001 |

| Variety (HOME) | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 2.60 (1.12) | 156 | 2.91 (1.07) | −0.31 (−0.58 to −0.05) | 0.283 | 0.020 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 3.01 (1.08) | 156 | 3.64 (0.92) | −0.63 (−0.87 to −0.39) | 0.628 | <0.001 |

| HOME Total | |||||||

| Baseline | 117 | 21.97 (7.91) | 156 | 22.62 (7.53) | −0.66 (−2.51 to 1.20) | 0.084 | 0.486 |

| 3rd month FU | 116 | 23.92 (8.56) | 156 | 31.73 (6.26) | −7.81 (−9.66 to −5.96) | 1.042 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Husain, N.; Sattar, R.; Kiran, T.; Husain, M.; Shakoor, S.; Suhag, Z.; Zadeh, Z.; Sikander, S.; Chaudhry, N. Effectiveness of Learning through Play Plus (LTP Plus) Parenting Intervention on Behaviours of Young Children of Depressed Mothers: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Children 2024, 11, 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060646

Husain N, Sattar R, Kiran T, Husain M, Shakoor S, Suhag Z, Zadeh Z, Sikander S, Chaudhry N. Effectiveness of Learning through Play Plus (LTP Plus) Parenting Intervention on Behaviours of Young Children of Depressed Mothers: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Children. 2024; 11(6):646. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060646

Chicago/Turabian StyleHusain, Nusrat, Rabia Sattar, Tayyeba Kiran, Mina Husain, Suleman Shakoor, Zamir Suhag, Zainab Zadeh, Siham Sikander, and Nasim Chaudhry. 2024. "Effectiveness of Learning through Play Plus (LTP Plus) Parenting Intervention on Behaviours of Young Children of Depressed Mothers: A Randomised Controlled Trial" Children 11, no. 6: 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060646

APA StyleHusain, N., Sattar, R., Kiran, T., Husain, M., Shakoor, S., Suhag, Z., Zadeh, Z., Sikander, S., & Chaudhry, N. (2024). Effectiveness of Learning through Play Plus (LTP Plus) Parenting Intervention on Behaviours of Young Children of Depressed Mothers: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Children, 11(6), 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060646