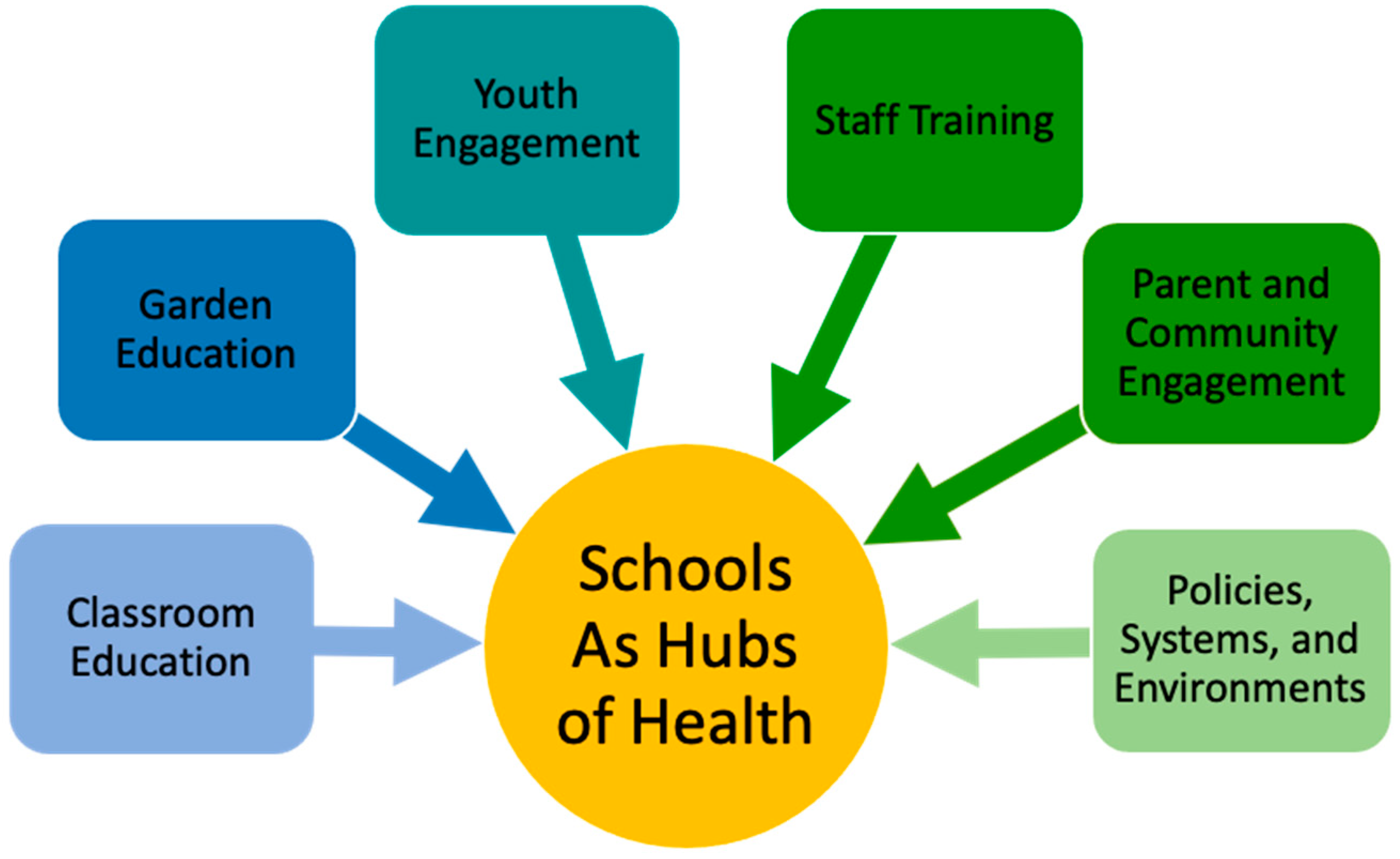

Schools as Hubs of Health: A Comprehensive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—Education Model for Promoting Wellness in Low-Income Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

1.2.1. Asset-Based Community Development

1.2.2. Health Equity

1.2.3. Positive Youth Development

1.2.4. Social Cognitive Theory

1.2.5. Trauma Informed Pedagogy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Classroom Education

2.2. Garden Education

2.3. Youth Engagement

2.4. Staff Training

2.5. Parent and Community Engagement

2.6. Policies, Systems, and Environments

3. Results

3.1. Classroom Education

3.1.1. Taste Test Tool Findings

3.1.2. Teacher Observation Tool (TOT)

3.1.3. Eating and Physical Activity Tool for Students (EATS)

3.1.4. Quotes and Reflections from Qualitative Feedback Surveys

- “Most of the kids said that they had only previously tasted white flour tortillas, not wheat tortillas. They were surprised that it tasted so good. The majority indicated that they would inform their parents as to the health benefits of choosing wheat tortillas over regular flour tortillas”.

- “The students loved trying the beets in a smoothie. Mixing it with fruit in a smoothie challenged them to try new things”.

- “Today in class we tasted fruits and vegetables some of them we like and some we didn’t”.

- “We made a veggie stir fry it tasted delicious”.

- “I notice that more students are eating the healthy choice. [YFC] is making a difference on our campus”.

- “Thank you for letting us try the garbanzo beans on their own, I never knew I would like them so much by themselves with nothing on them. I am going to look for them on the salad bar next time!”

- “I loved (the Brussels Sprouts) so much I’m going to go ask the (Lunch Staff) if we can have these on our lunch line so I can eat them again!”

3.2. Garden Education

- “Learning new stuff for cooking and garden. It has helped my garden”. (2023)

- “Getting to teach younger kids about Ag the way I wish I would’ve been taught”. (2023)

- “The best part was being able to learn new things about plants while being able to teach others about new things. Also being able to eat what we grew”. (2022)

3.3. Youth Engagement

- Increased positive health behaviors, leadership, teaching, cooking, gardening, and self-confidence among participants.

- Notable outcomes include increased nutrition knowledge, behavior changes, and improved skills in presentation, leadership, and cooking.

- Post-program surveys indicated significant improvements in healthy behaviors, such as choosing water over sugary drinks and consuming smaller servings of high-fat foods.

- Youth development measures revealed enhanced decision-making abilities, community involvement, and leadership skills.

- Statistically significant positive youth development outcomes were documented, including gains in public speaking, program planning, and teaching.

- Participants reported knowledge gains and anticipated behavior changes related to leadership and peer teaching.

- Notable impacts from the 2021/2022 academic year include enhanced leadership skills, improved health behaviors, and positive qualitative feedback highlighting the program’s benefits.

- “I like the nutrition club. It helps me to eat healthy food. It also helps me to do exercise every day. I also like how we do a lot of fun things.”

- “I like to jump rope. They let us use knives. And they let us eat. And they let us plant. And they let us cook.”

- “We got to exercise and meet new people. We also go to tell other people about [4-H S.N.A.C. Club] and how it’s important and useful. It’s really fun being in [4-H S.N.A.C. Club] because we get to do presentations, exercise, cook healthy, and make healthy things.”

- “I enjoy seeing other kids’ expressions trying new foods. I also like to talk to my family about it.”

3.4. Staff Training

- “The experience of engaging and empowering youth to make healthier choices and to also teach their peers to make healthier choices has been very encouraging and rewarding. I have witnessed many individual and group successes from the youth that we are working with within a short time period. Many of the youth we have worked with have gained an abundance of confidence in expressing their knowledge of nutrition, health, and physical activity and building their skill set for public speaking and project development. They are becoming more comfortable taking the initiative on creating and developing the projects that are most important to them”.

- “The things [students] learned are really sticking with them. They are reading nutrition labels and identifying healthier choices”.

- “Very informative! I learned things I didn’t know, surprised at what I did know. This was fun”.

- “I would also like to somehow teach students to take only what they can eat. To not take so much that they have to toss food”.

- “Enjoyed learning how to make food look better and how to make the lunchroom environment better. I think it’s great that we are working on bettering our lunch site”.

- “Good ideas to bring back to our work force. Always good to have a fresh look at things. Wish I would have taken your workshop sooner”.

- “Excellent ideas to get kids to eat more by appealing visuals”.

- “Idea of having input from students i.e., food names. I will give it a try!”

- “I feel like small changes can be made for big results”.

3.5. Parent and Community Engagement

- “I like how it tastes and I would make this for my family”.

- “I’ve changed many things at home. My children found it fun when I shared how to properly clean hands, fruit, and countertops. Everything was fun. Some of my favorite techniques that I learned: how to prevent spread of bacteria, how to organize the fridge, use different cutting boards. I enjoyed learning how to take care of my home and family. Thank you!”

- “I have learned to pay more attention to what I’m eating and what I’m feeding my son. There is a variety of foods that I like that are healthy for me so now I substitute those foods with the unhealthy foods I like”.

- “A mi familia nos ha cambiado mucho la manera de como comer saludable y mas economico. Menos gastamos en comprar cosas malas. Mis hijos les gusta lo que les han ensenado en sus clases que se queda con este programa, y por eso me gusta porque mis hijos ya no les gusta comer cosas que no son saludables. Gracias por este programa, esta muy bien ayudando a nuestros hijos”. [English translation: My family has changed a lot about the way we eat healthier and more economical. We spend less money on buying bad things. My children that are with your program, like what they have been learning in their classes. I like the program because my children no longer like to eat things that are not healthy. Thanks for this program, it’s very good and helps our children].

- “Aprendemos comer más saludable y estar más sano con la familia”. [English translation: We learned how to eat healthier and to be a healthier family].

- “Aprendo tomar mucha agua y consumar la menor azucar possible”. [English translation: I learned to drink more water and to consume as little sugar as possible].

- “Aprendí que comer frutas y verduras es saludable en la vida, para los niños es muy importante”. [English translation: I learned that eating fruits and vegetables is healthy for your life, and is very important for the kids].

3.6. Policies, Systems, and Environments (PSE)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

- Challenges in evaluating comprehensive, longitudinal programming, particularly in capturing the cumulative impacts of multifaceted interventions.

- Difficulty in assessing changes in behavior over time due to the dynamic nature of youth development and the lack of consistent data collection methods.

- Limited comparability between school-based SNAP-Ed interventions and non-school interventions, hindering comprehensive evaluation and analysis.

4.2. Future Research

4.2.1. Evaluation of Comprehensive, Longitudinal Programming

- Current evaluation tools available to SNAP-Ed implementers may not adequately capture the overall impacts of such programming. Future research should focus on developing and refining evaluation methodologies to better quantify the cumulative impacts of comprehensive interventions.

- Longitudinal studies that track youth from early grades (T-K) through sixth grade can provide valuable insights into the long-term effects of school-based interventions. However, existing pre/post-evaluation tools may not be sufficient in capturing developmental changes in behavior over time.

- Comparative research between school-based SNAP-Ed interventions and non-school interventions is needed to assess their respective reach and impact. Standardized data collection and reporting protocols should be established to facilitate meaningful comparisons across different intervention settings.

4.2.2. Evaluation of Policy, System, and Environmental (PSE) Efforts

- Environmental scan tools play a crucial role in identifying priorities and initiating conversations with stakeholders. However, their effectiveness in measuring changes over time at site or institutional levels may be limited.

- Future research should explore innovative approaches to evaluating PSE efforts, with a focus on developing more precise and comprehensive measurement tools.

4.2.3. Community Engagement in Evaluation Processes

- While current evaluation tools may be meaningful to funders, there is a need to incorporate additional measures that are relevant and meaningful to program participants, partners, and communities.

- Greater community engagement in the evaluation planning process is essential to ensure that evaluation indicators align with the needs and priorities of stakeholders.

- Efforts to address evaluation fatigue and minimize participant burden are crucial for maintaining engagement and participation in longitudinal evaluation studies.

- Evaluation planning should prioritize the inclusion of measures that resonate with youth, families, and school administrators, thus providing a more holistic understanding of program impacts.

4.3. Implications for Practice

- Prioritize effective collaboration with school and community partners, ensuring that each partners’ contributions, goals, limitations, and needs are identified and addressed through the program. Programming that minimizes the need for and role of partners is likely to encounter additional barriers, as well as miss meaningful opportunities to positively impact community health and wellbeing.

- Prioritize the hiring of educators who reflect the youth population and have shared lived experiences, as individuals who live, work, and play in the site communities have a robust and personal understanding of the needs and strengths of the participants, as well as the environments and systems that impact health and wellbeing.

- Engage youth, staff, and community partners in decision-making processes to foster ownership and empowerment within the program. Youth, staff, and community partners should be incorporated into decision-making roles to ensure significant and meaningful contributions to program content development and delivery.

- Recognize and harness the potential of youth as agents of change, empowering them to educate peers, families, and communities on health-related topics. Prior research highlights how youth can positively influence familial and community behaviors [41,44,45]. Training and supporting youth to teach others build their nutrition and physical activity knowledge, while supporting skill development to prepare them for future community-building, civic engagement, and college/career readiness.

- Diversify funding sources beyond SNAP-Ed to enable flexibility and innovation in program design and implementation. Even small amounts of diversified funding enable the program to be responsive to the needs of community members and to develop creative solutions that are not allowable per USDA guidelines.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.; Rehm, C.D.; Onopa, J.; Mozaffarian, D. Trends in Diet Quality Among Youth in the United States, 1999–2016. JAMA 2020, 323, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 2020. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Micha, R.; Peñalvo, J.L.; Cudhea, F.; Imamura, F.; Rehm, C.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017, 317, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelino, D.; Godos, J.; Ghelfi, F.; Tieri, M.; Titta, L.; Lafranconi, A.; Marventano, S.; Alonzo, E.; Gambera, A.; Sciacca, S.; et al. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Observational Studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- USDA; SNAP. FY 2024 Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) Plan Guidance, Nutrition Education and Obesity Prevention Program. 2024. Available online: https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/library/materials/fy-2024-snap-ed-plan-guidance- (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Food and Nutrition Services. Food and Nutrition Act of 2008; Food and Nutrition Services: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2023.

- Burke, M.P.; Gleason, S.; Singh, A.; Wilkin, M.K. Policy, Systems, and Environmental Change Strategies in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education (SNAP-Ed). J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodder, R.K.; O’Brien, K.M.; Lorien, S.; Wolfenden, L.; Moore, T.H.M.; Hall, A.; Yoong, S.L.; Summerbell, C. Interventions to Prevent Obesity in School-Aged Children 6-18 Years: An Update of a Cochrane Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Including Studies from 2015–2021. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, L.; Wu, Y.; Wilson, R.F.; Weston, C.; Fawole, O.; Bleich, S.N.; Cheskin, L.J.; Showell, N.N.; Lau, B.D.; et al. What Childhood Obesity Prevention Programmes Work? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Micha, R.; Li, Y.; Mozaffarian, D. Trends in Food Sources and Diet Quality Among US Children and Adults, 2003–2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e215262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, C.; Smarsh, B.L.; Xiao, X. School Nutrition Environment and Services: Policies and Practices That Promote Healthy Eating Among K-12 Students. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Szucs, L.E.; Young, E.; Fahrenbruch, M. Using Health Education to Address Student Physical Activity and Nutrition: Evidence and Implications to Advance Practice. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2017 Environmental Justice Implementation Progress Report; United States Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Chitewere, T.; Shim, J.K.; Barker, J.C.; Yen, I.H. How Neighborhoods Influence Health: Lessons to Be Learned from the Application of Political Ecology. Health Place 2017, 45, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetter, D.S.; Scherr, R.E.; Linnell, J.D.; Dharmar, M.; Schaefer, S.E.; Zidenberg-Cherr, S. Effect of the Shaping Healthy Choices Program, a Multicomponent, School-Based Nutrition Intervention, on Physical Activity Intensity. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veitch, J.; Carver, A.; Salmon, J.; Abbott, G.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Cleland, V.; Timperio, A. What Predicts Children’s Active Transport and Independent Mobility in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods? Health Place 2017, 44, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthy People 2030. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- McCormick, B.A.; Porter, K.J.; You, W.; Yuhas, M.; Reid, A.L.; Thatcher, E.J.; Zoellner, J.M. Applying the Socio-Ecological Model to Understand Factors Associated with Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Behaviours among Rural Appalachian Adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3242–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellou, N.; Sandalinas, F.; Copin, N.; Simon, C. Prevention of Unhealthy Weight in Children by Promoting Physical Activity Using a Socio-Ecological Approach: What Can We Learn from Intervention Studies? Diabetes Metab. 2014, 40, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, D.; Contento, I.R.; Weekly, C. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior, and School Nutrition Association: Comprehensive Nutrition Programs and Services in Schools. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabravolskaj, J.; Montemurro, G.; Ekwaru, J.P.; Wu, X.Y.; Storey, K.; Campbell, S.; Veugelers, P.J.; Ohinmaa, A. Effectiveness of School-Based Health Promotion Interventions Prioritized by Stakeholders from Health and Education Sectors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 19, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, C.M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.L.; Inskip, H.M.; Morris, T.; Parsons, C.M.; Barrett, M.; Hanson, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of School-Based Interventions with Health Education to Reduce Body Mass Index in Adolescents Aged 10 to 19 Years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.S.; Sliwa, S.A.; Merlo, C.; Erwin, H.; Xu, Y. Coordinated Approach: Comprehensive Policy and Action Planning. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Harwell, O.R.; Sliwa, S.A.; Hawkins, G.T.; Michael, S.; Merlo, C.; Pitt Barnes, S.; Chung, C.S.; Cornett, K.; Hunt, H. Transforming Evidence Into Action: A Commentary on School-Based Physical Activity and Nutrition Intervention Research. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, K.; Comerford, T.; Deavin, N.; Walton, K. Characteristics of Successful Primary School-Based Experiential Nutrition Programmes: A Systematic Literature Review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4642–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, S.L.; Barnes, S.P.; Wilkins, N.J. Scoping Review of Family and Community Engagement Strategies Used in School-Based Interventions to Promote Healthy Behaviors. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 828–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornett, K.; Murfay, K.; Fulton, J.E. Physical Activity Interventions During the School Day: Reviewing Policies, Practices, and Benefits. J. Sch. Health 2023, 93, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, D.; Canto, A.; Coon, T.; Eschbach, C.; Gutter, M.; Jones, M.; Kennedy, L.; Martin, K.; Mitchell, A.; O’Neal, L.; et al. Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health Equity and Well Being; Extension Committee on Organization and Policy Health Innovation Task Force: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child: A Collaborative Approach to Learning and Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2014.

- Drouka, A.; Brikou, D.; Causeret, C.; Al Ali Al Malla, N.; Sibalo, S.; Ávila, C.; Alcat, G.; Kapetanakou, A.E.; Gurviez, P.; Fellah-Dehiri, N.; et al. Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions in Europe for Promoting Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors in Children. Children 2023, 10, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Heath and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2010; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Ife, J. Community Development in an Uncertain World: Vision, Analysis and Practice, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WSCC Health Equity in Schools Module. 2020. Available online: https://www.sophe.org/resources/wscc-health-equity-module/ (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Office of Population Affairs. Health and Human Services. Positive Youth Development. Office of Population Affairs. Available online: https://opa.hhs.gov/adolescent-health/positive-youth-development (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network Schools Committee. Child Trauma Toolkit for Educators; National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Durham, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karhan, A. Trauma-Informed Policy for Youth: Structuring Policies and Programs to Support the Future of Work. 2021. Available online: https://capeyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2021/10/CAPE_Youth_TraumaInformedPolicyforYouth.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Klisch, S.; Diaz, M.; Dimond, E.; Hong, K.; Marrs, A.; Plascencia, B.; Rorabough, M.; Vargas, R.; Soule, K.E. 4-H S.N.A.C Club (Student Nutrition Advisory Council). 2023. Available online: https://shop4-h.org/products/4-h-s-n-a-c-club (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Klisch, S.; Soule, K.E. 4-H Student Nutrition Advisory Councils Support Positive Youth Development and Health Outcomes among Underserved Populations. J. Ext. 2021, 59, 19. Available online: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/joe/vol59/iss3/19/ (accessed on 28 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.M.; Horrillo, S.J.; Widaman, K.; Worker, S.M.; Trzesniewski, K. National 4-H Common Measures: Initial Evaluation from California 4-H. J. Ext. 2015, 53, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Klisch, S. Cooking Together (Virtually) to Build Community and Promote Healthy during COVID-19. J. Natl. Ext. Assoc. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2022, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, H.; Ardoin, N.M.; Flora, J.; Armel, K.C.; Desai, M.; Robinson, T.N. Effects of a Behaviour Change Intervention for Girl Scouts on Child and Parent Energy-Saving Behaviours. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damerell, P.; Howe, C.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Child-Orientated Environmental Education Influences Adult Knowledge and Household Behavior. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Academic Year | No. of Classes | No. of Students | % of Students Trying This Food for the First Time | % of Students Willing to Eat This Food Again | % of Students Willing to Ask for This Food at Home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014/15 | 117 | 3420 | 39% | 73% | 69% |

| 2015/16 | 48 | 1357 | 35% | 79% | 71% |

| 2016/17 | 39 | 1067 | 36% | 69% | 63% |

| 2017/18 | 32 | 831 | 59% | 76% | 71% |

| 2018/19 | 21 | 540 | 56% | 69% | 65% |

| Academic Year | No. of Classes | No. of Students | % of Teachers Reporting That More Students Can Identify Healthy Food Choices at the End of the School Year | % of Teachers Reporting That More Students Are Willing to Try New Foods at School at the End of the School Year | % of Teachers Reporting That More Students Choose Fruits and Vegetables at the End of the School Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014/15 | 79 | 2378 | 96% | 96% | 75% |

| 2015/16 | 44 | 1371 | 100% | 95% | 78% |

| 2016/17 | 59 | 1684 | 98% | 86% | 65% |

| 2017/18 | 45 | 1264 | 98% | 95% | 74% |

| 2018/19 | 33 | 810 | 100% | 97% | 63% |

| Academic Year | % of Students Who Reported an Increase in Overall Fruit Consumption | % of Students Who Reported an Increase in Overall Vegetable Consumption | % of Students Who Reported a Decrease in Consumption of Sweetened Beverages | % of Students Who Reported an Increase in the Number of Days They Engaged in 60+ min of Physical Activity Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021/22 | 36% (n = 91) | 28% (n = 91) | No data | 63% (n = 91) |

| 2022/23 | 37% (n = 133) | 35% (n = 121) | 44% (n = 122) | 52% (n = 127) |

| Academic Year. | N | Compared to the Beginning of the Year, I Now Make My Own Healthier Food Choices | Compared to the Beginning of the Year, I Now Remind Families to Bring Healthy Snacks | Compared to the Beginning of the Year, I Now Encourage the Students to Be Active | Compared to the Beginning of the Year, I Now Offer Students Healthy Choices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014/15 | 79 | 64% | 59% | 77% | 57% |

| 2015/16 | 41 | 66% | 66% | 73% | 71% |

| 2016/17 | 51 | 66% | 98% | 61% | 59% |

| 2017/18 | 42 | 55% | 69% | 79% | 69% |

| 2018/19 | 33 | 68% | 61% | 68% | 65% |

| 2022/23 | 18 | 82% | 70% | 89% | 70% |

| Academic Year | # of PSE Changes Adopted | # of People Reached |

|---|---|---|

| 2015/16 | 30 | 2908 |

| 2016/17 | 40 | 8791 |

| 2017/18 | 56 | 7179 |

| 2018/19 | 31 | 3647 |

| 2019/20 | 103 | 39,881 |

| 2020/21 | 25 | 4121 |

| 2021/22 | 37 | 1804 |

| 2022/23 | 40 | 2625 |

| Total | 362 | 70,956 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klisch, S.A.; Soule, K.E. Schools as Hubs of Health: A Comprehensive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—Education Model for Promoting Wellness in Low-Income Communities. Children 2024, 11, 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050525

Klisch SA, Soule KE. Schools as Hubs of Health: A Comprehensive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—Education Model for Promoting Wellness in Low-Income Communities. Children. 2024; 11(5):525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050525

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlisch, Shannon A., and Katherine E. Soule. 2024. "Schools as Hubs of Health: A Comprehensive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—Education Model for Promoting Wellness in Low-Income Communities" Children 11, no. 5: 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050525

APA StyleKlisch, S. A., & Soule, K. E. (2024). Schools as Hubs of Health: A Comprehensive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—Education Model for Promoting Wellness in Low-Income Communities. Children, 11(5), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050525