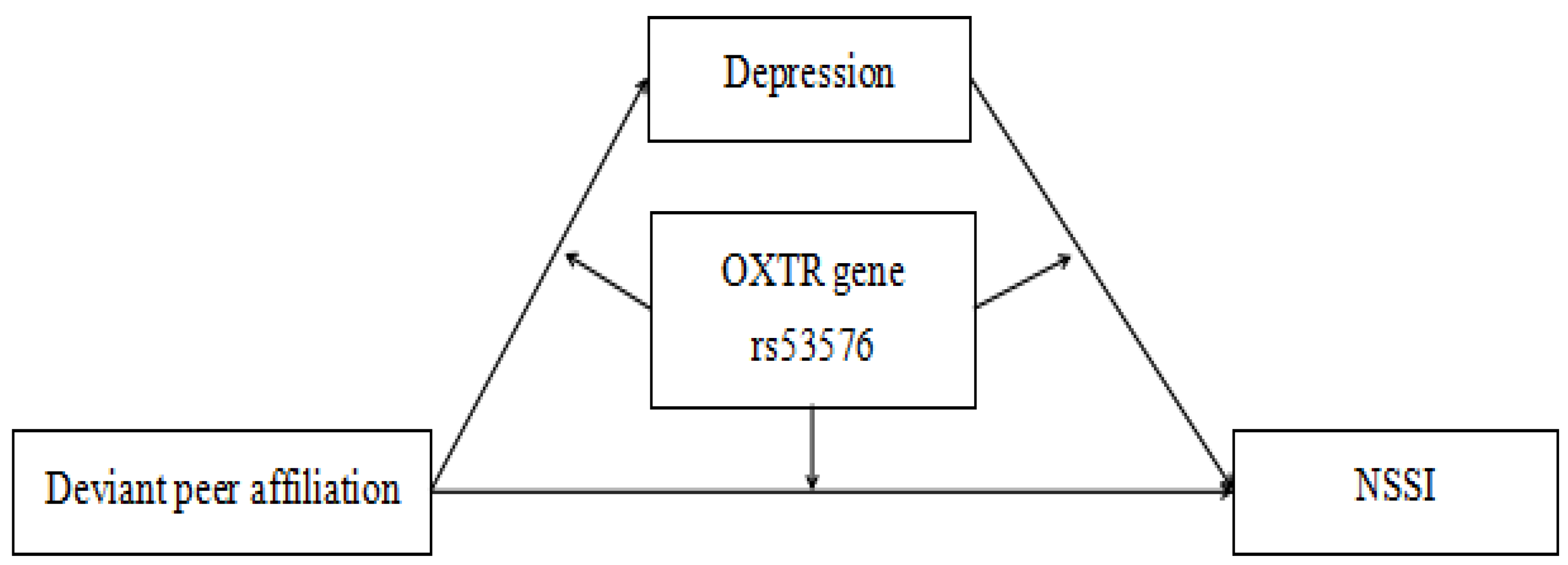

Deviant Peer Affiliation, Depression, and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Moderating Effect of the OXTR Gene rs53576 Polymorphism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Deviant Peer Affiliation and NSSI

1.2. Mediating Effect of Depression

1.3. Moderating Effect of OXTR rs53576

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Deviant Peer Affiliation

2.2.2. Depression

2.2.3. NSSI

2.2.4. Genotyping

2.2.5. Family Financial Difficulties

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Testing for the Mediation Effect of Depression

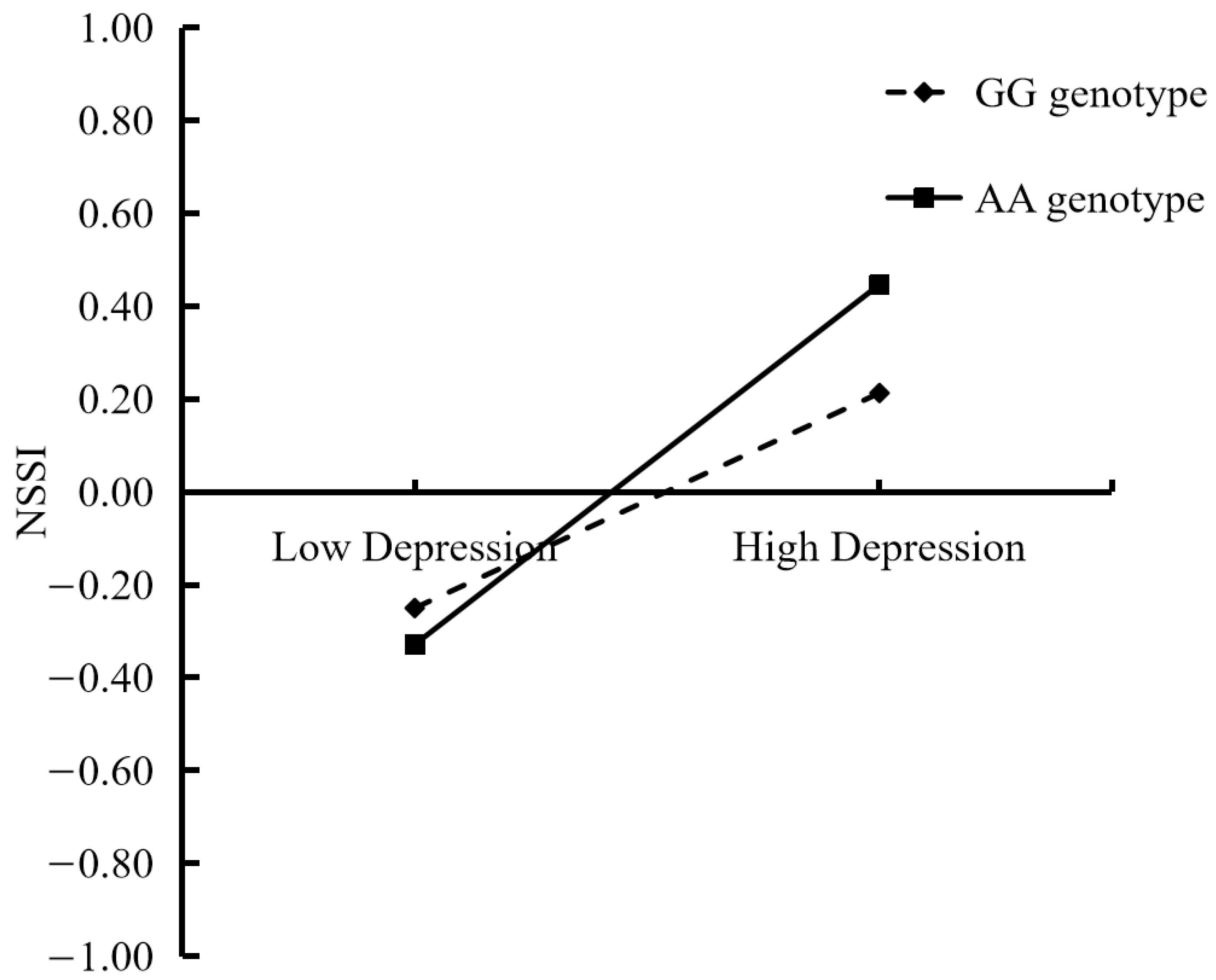

3.3. Moderating Effect of the OXTR Gene rs53576 Polymorphism

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nock, M.K. Self-injury. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2010, 6, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Y.; Su, B.; Zhang, W. Anxiety symptoms mediates the influence of cybervictimization on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The moderating effect of self-control. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 285, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Ren, Y.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, S.; You, J. Self-compassion and Family Cohesion Moderate the Association between Suicide Ideation and Suicide Attempts in Chinese adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Huang, J.; Ying, J.; Gao, Q.; Guo, J.; You, J. Behavioral inhibition/approach systems and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: The chain mediating effects of difficulty in emotion regulation and depression. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 175, 110718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, C.; McRoy, R.; O’Brien, K. Substance use and suicidal ideation among child welfare involved adolescents: A longitudinal examination. Addict. Behav. 2019, 93, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Kingsbury, M.; Bennett, K.; Manion, I.; Colman, I. Adolescents’ knowledge of a peer’s non-suicidal self-injury and own non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Acta. Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 142, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 1992, 30, 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R.; White, H. An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology 2006, 30, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahase, E. Depression: EU approves expanded use of esketamine for rapid reduction of symptoms. BMJ 2021, 372, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Building on the Foundation of General Strain Theory: Specifying the Types of Strain Most Likely to Lead to Crime and Delinquency. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2001, 38, 319–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Heilbron, N.; Guerry, J.D.; Franklin, J.C.; Rancourt, D.; Simon, V.; Spirito, A. Peer influence and nonsuicidal self injury: Longitudinal results in community and clinically-referred adolescent aamples. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilt, L.M.; Hamm, E.H. Peer Influences on Non-suicidal Self-Injury and Disordered Eating. In Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Eating Disorders; Claes, L., Muehlenkamp, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca, P.A.; Vivien, S.H. Relationship between academic stress and suicidal ideation: Testing for depression as a mediator using multiple regression. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2006, 37, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Childhood emotional abuse and depression among adolescents: Roles of deviant peer affiliation and gender. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP830–NP850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briley, P.; Gerlach, H.; Jacobs, M. Relationships between stuttering, depression, and suicidal ideation in young adults: Accounting for gender differences. J. Fluen. Disord. 2021, 67, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K.; Garisch, J.; Wilson, M. Nonsuicidal self-injury thoughts and behavioural characteristics: Associations with suicidal thoughts and behaviours among community adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1247–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden, P.; Stewart, S.L.; Fallon, B. The mediating effect of depressive symptoms on the relationship between bullying victimization and non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Findings from community and inpatient mental health settings in Ontario, Canada. Psy. Res. 2017, 255, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.C.; Li, Q. Adolescent delinquency in child welfare system: A multiple disadvantage model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 73, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van IJzendoorn, M.H. For Better and For Worse: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boduszek, D.; Debowska, A.; Ochen, E.; Fray-Aiken, C.; Nanfuka, E.; Powell-Booth, K.; Turyomurugyendo, F.; Nelson, K.; Harvey, R.; Willmott, D.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempt among children and adolescents: Findings from Uganda and Jamaica. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 283, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RadloffPark, Y.; Ammerman, B. How Should We Respond to Non-suicidal Self-Injury Disclosures?: An Examination of Perceived Reactions to Disclosure, Depression, and Suicide Risk. Psy. Res. 2020, 293, 113430. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.; Silamongkol, T.; Wiglesworth, A.; Labella, M.; Goetz, E.; Cullen, K.; Klimes-Dougan, B. Maternal Emotion Socialization of Adolescent Girls Engaging in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K. Measurement of Deliberate Self-Harm: Preliminary Data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2001, 23, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Wang, C.; Dong, Y.; He, S. Oxytocin receptor gene polymorphisms moderate the relationship between job stress and general trust in Chinese Han university teachers. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 260, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, W. Childhood trauma, parent-child conflict and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The moderating role of oxytocin receptor gene rs53576 polymorphism. J. Chin. Youth Soc. Sci. 2021, 40, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Theodoridou, A.; Rowe, A.C.; Penton-Voak, I.S.; Rogers, P.J. Oxytocin and social perception: Oxytocin increases perceived facial trustworthiness and attractiveness. Horm. Behav. 2009, 56, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebowitz, E.; Blumberg, H.; Silverman, W. Negative Peer Social Interactions and Oxytocin Levels Linked to Suicidal Ideation in Anxious Youth. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 245, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; Sugden, K.; Moffitt, T.E.; Taylor, A.; Craig, I.W.; Harrington, H.; Poulton, R. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003, 301, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewska, K.; Pawlak, A.; Kostrzewa, G.; Sobczyk-Kopciol, A.; Kaczorowska, A.; Badowski, J.; Ploski, R. OXTR polymorphism in depression and completed suicide-A study on a large population sample. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 77, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, W.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yu, C. Neural Mechanisms of Oxytocin Receptor Gene Mediating Anxiety—Related Temperament. Brain Struct. Funct. 2014, 219, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.P.; Li, D.P.; Zhang, W. The relationship between family financial difficulties and adolescents’ social adjustment: The compensatory, mediating and moderating effects of coping effectiveness. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 4, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Kumsta, R.; Dawans, B.; Monakhov, M.; Ebstein, R.; Heinrichs, M. Common oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphism and social support interact to reduce stress in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19937–19942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moons, W.G.; Way, B.M.; Taylor, S.E. Oxytocin and vasopressin receptor polymorphisms interact with circulating neuropeptides to predict human emotional reactions to stress. Emotion 2014, 14, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Tsuchiya, K.; Takei, N. Interaction effect of oxytocin receptor (OXTR) rs53576 genotype and maternal postpartum depression on child behavioural problems. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, C.F.; Bao, Z.Z. Early adolescent Internet game addiction in context: How parents, school, and peers impact youth. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psych. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Dukewich, T.L.; Roeder, K.; Sinclair, K.R.; McMillan, J.; Will, E.; Fecton, J.W. Linking peervictim- ization to the development of depressive self-schemas in children and adolescents. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.D.; Espelage, D.L. Mediating the bullying victimizationdelinquency relationship with anger and cognitive impulsivity: A test of general strain and criminal lifestyle theories. J. Crim. Justice 2017, 53, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T.; Campbell, S.B. Developmental Psychopathology and Family Process: Theory, Research, and Clinical Implications; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Uher, R.; Dernovsek, M.Z.; Mors, O.; Hauser, J.; Souery, D.; Zobel, A.; Maier, W.; Henigsberg, N.; Kalember, P.; Rietschel, M.; et al. Melancholic, atypical and anxious depression subtypes and outcome of treatment with escitalopram and nortriptyline. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 132, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2. Age | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3. FFD | −0.03 | 0.05 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. DPA | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.21 *** | 1.00 | ||||

| 5. Depression | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.18 *** | 0.27 *** | 1.00 | |||

| 6. NSSI | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.18 *** | 0.31 *** | 1.00 | ||

| 7. Gene AA a | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 1.00 | |

| 8. Gene GA b | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.85 *** | 1.00 |

| Mean | — | 12.81 | 1.32 | 1.40 | 1.69 | 1.05 | — | — |

| SD | — | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.20 | — | — |

| Equation 1 (Depression) | Equation 2 (NSSI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Covariates: | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.09 | 1.91 | [−0.01, 0.34] | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.47 | [−0.13, 0.22] |

| Age | 0.08 | 0.04 | 1.82 | [−0.01, 0.17] | −0.05 | 0.04 | −1.18 | [−0.14, 0.03] |

| FFD | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.78 ** | [0.04, 0.21] | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.21 | [−0.08, 0.10] |

| Study variables: | ||||||||

| DPA | 0.24 | 0.05 | 5.34 *** | [0.15, 0.33] | 0.10 | 0.05 | 2.16 * | [0.01, 0.19] |

| Depression | 0.29 | 0.05 | 6.16 *** | [0.19, 0.38] | ||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.11 | ||||||

| F | 12.81 *** | 11.44 *** | ||||||

| Equation 1 (Depression) | Equation 2 (NSSI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Covariates: | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.18 | 0.09 | 2.01 | [−0.00, 0.34] | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.19 | [−0.19, 0.20] |

| Age | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.89 | [−0.04, 0.21] | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.38 | [−0.17, 0.02] |

| FFD | 0.13 | 0.05 | 2.85 ** | [0.03, 0.22] | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.08, 0.09] |

| Study variables: | ||||||||

| DPA | 0.44 | 0.22 | 2.12 * | [0.00, 0.89] | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.04 | [−0.12, 0.18] |

| Gene AA a | −0.25 | 0.18 | −1.51 | [−0.63, 0.07] | 0.24 | 0.11 | 1.43 | [0.04, 0.47] |

| Gene GA b | −0.16 | 0.18 | −0.96 | [−0.54, 0.17] | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.97 | [0.02, 0.30] |

| DPA × Gene AA | −0.23 | 0.23 | −1.04 | [−0.68, 0.24] | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.44 | [−0.13, 0.34] |

| DPA × Gene GA | −0.19 | 0.24 | −0.84 | [−066, 0.29] | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.34 | [−0.12, 0.25] |

| Depression | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.67 | [−0.01, 0.21] | ||||

| Depression × Gene AA | 0.28 | 0.15 | 1.74 * | [0.02, 0.60] | ||||

| Depression × Gene GA | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.78 | [−0.08, 0.40] | ||||

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.13 | ||||||

| F | 6.88 *** | 5.97 *** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Yu, C. Deviant Peer Affiliation, Depression, and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Moderating Effect of the OXTR Gene rs53576 Polymorphism. Children 2024, 11, 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121445

Li J, Yu C. Deviant Peer Affiliation, Depression, and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Moderating Effect of the OXTR Gene rs53576 Polymorphism. Children. 2024; 11(12):1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121445

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jingjing, and Chengfu Yu. 2024. "Deviant Peer Affiliation, Depression, and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Moderating Effect of the OXTR Gene rs53576 Polymorphism" Children 11, no. 12: 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121445

APA StyleLi, J., & Yu, C. (2024). Deviant Peer Affiliation, Depression, and Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Moderating Effect of the OXTR Gene rs53576 Polymorphism. Children, 11(12), 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121445