Stress in Family Caregivers of Children with Chronic Health Conditions: A Case–Control Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

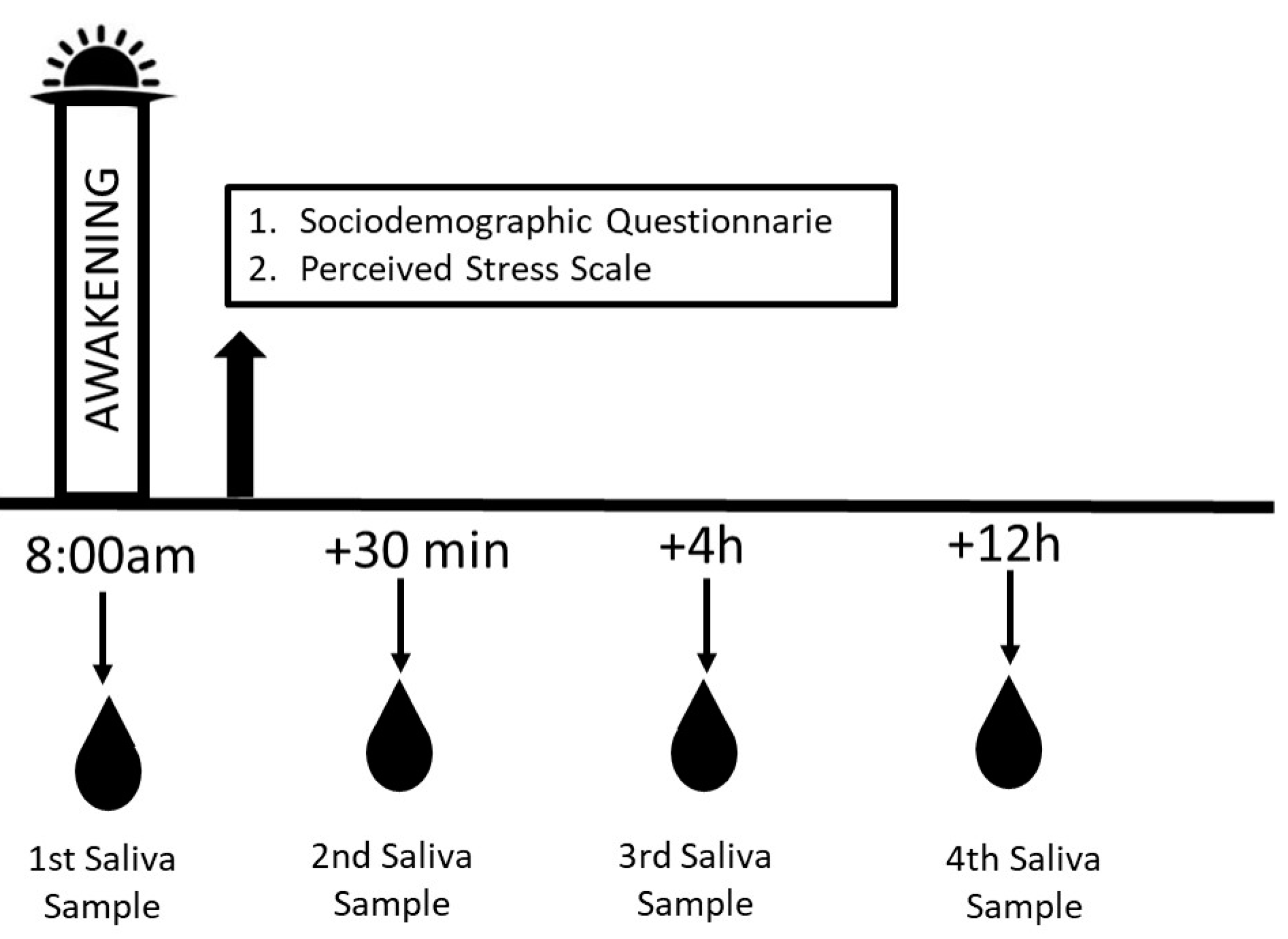

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Analysis of Perceived Stress

3.3. Analysis of Salivary Cortisol

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stein, R.E.; Bauman, L.J.; Westbrook, L.E.; Coupey, S.M.; Ireys, H.T. Framework for identifying children who have chronic conditions: The case for a new definition. J. Pediatr. 1993, 122, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M. Parenting Stress in Caregivers of Children with Chronic Physical Condition—A Meta-Analysis. Stress Health 2018, 34, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilty, K.; Nicholas, D.; Selkirk, E. Experiences with Unregulated Respite Care among Family Caregivers of Children Dependent on Respiratory Technologies. J. Child Health Care 2018, 22, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, L.K.; Miller, M.; Hain, R.; Norman, P.; Aldridge, J. Health of Mothers of Children with a Life-Limiting Condition: A Comparative Cohort Study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, K.; Naseri, M.; Savari, Y. Evaluating the Role of Perceived Stress, Social Support, and Resilience in Predicting the Quality of Life among the Parents of Disabled Children. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2023, 70, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noushad, S.; Aldhafiri, H.; Jatoi, N.; Alnafisah, R.; Rizwan, A.; Siddiqui, M.A. Biomarkers of Chronic Stress: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Health Sci. 2021, 15, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Mountcastle, L.; Harris, J.; Fox, N.A.; Nelson, C.A. The Impact of Caregiving for Children with Chronic Conditions on the HPA Axis: A Scoping Review. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 71, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, M.; Ray, D.W. Circadian Rhythms in Innate Immunity and Stress Responses. Immunology 2020, 161, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; Crosswell, A.D.; Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Slavich, G.M.; Puterman, E.; Mendes, W.B. More than a Feeling: A Unified View of Stress Measurement for Population Science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crielaard, L.; Andreeva, T.I.; Bracke, P.; Buskens, V.; Thomeer, M.B. Understanding the Impact of Exposure to Adverse Socioeconomic Conditions on Chronic Stress from a Complexity Science Perspective. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Toledano, F.; Domínguez-Guedea, M.T. Psychosocial Factors Related with Caregiver Burden among Families of Children with Chronic Conditions. BioPsychoSoc. Med. 2019, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulley, S.B.; Cummings, S.R.; Browner, W.S.; Grady, D.G.; Newman, T.B. Designing Clinical Research, 4th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling. SAGE Res. Methods Found. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Karmack, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, C.D.B.; Sanches, S.O.; Mazo, G.Z.; Andrade, A. Versão Brasileira da Escala de Estresse Percebido: Tradução e Validação para Idosos. Rev. Saúde Pública 2007, 41, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Kirschbaum, C.; Meinlschmid, G.; Hellhammer, D.H. Two Formulas for Computation of the Area under the Curve Represent Measures of Total Hormone Concentration versus Time-Dependent Change. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, G. Mothers with Disabled Children: Needs, Stress Levels, and Family Functionality in Rehabilitation. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 34, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, B.J.; Ferreira, F.Y.; Rocha Paes, L.D.C.; Garcia Lima, R.A.; Cavicchioli Okido, A.C. Perceived Stress in Mothers of Children with Special Health Care Needs and Related Sociodemographic Factors. Cienc. Cuid. Saúde 2023, 22, 65793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.S.D.; Moraes, O.F.; Sabin, L.D.; Almeida, F.O.; Magnago, T.S.B.D. Resiliência de cuidadores familiares de crianças e adolescentes em tratamento de neoplasias e fatores associados. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2021, 74, e20190388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, N.; Shankhwar, S. Caregiver Burden among Primary Caregivers of Children with Intellectual Development Disorder and Its Association with Perceived Stress. NeuroQuantology 2023, 21, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, H.L.; Mancini, M.; Mendonça, S.; Paes, L.D.C. Necessidades de Cuidadores de Crianças com Transtorno de Neurodesenvolvimento: Overview. Rev. APS 2021, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, G.P.; Garcia, M.C.; Spadari-Bratfisch, R.C. Salivary Cortisol, Stress, and Health in Primary Caregivers (Mothers) of Children with Cerebral Palsy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padden, C.; James, J.E. Stress among Parents of Children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comparison Involving Physiological Indicators and Parent Self-Reports. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2017, 29, 567–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojnowska, S.; Walczak, M.; Talarowska, M.; Szemraj, J.; Wieczorek, E. Salivary Biomarkers of Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Schipper, H.M.; Velly, A.M.; Mohit, S.; Gornitsky, M. Salivary Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress: A Critical Review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 85, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubičić, M.; Ilić, K.; Colić, M.; Reljić, D.; Marković, A.; Stančić, N.; Savić, T. Awakening Cortisol Indicators, Advanced Glycation End Products, Stress Perception, Depression and Anxiety in Parents of Children with Chronic Conditions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 117, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecteau, S.M.; Dufault, B.; Lacroix, A.; Tremblay, M.-P.; Paquette, M. Parenting Stress and Salivary Cortisol in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Longitudinal Variations in the Context of a Service Dog’s Presence in the Family. Biol. Psychol. 2017, 123, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykens, E.M.; Lambert, W. Trajectories of diurnal cortisol in mothers of children with autism and other developmental disabilities: Relations to health and mental health. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2426–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Roos, L.G.; Mengelkoch, S.; Webb, C.A.; Shattuck, E.C.; Moriarity, D.P.; Alley, J.C. Social Safety Theory: Conceptual foundation, underlying mechanisms, and future directions. Health Psychol. Rev. 2023, 17, 5–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Case | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Family caregiver’s age | 38.22 (6.88) | 38.16 (6,08) |

| Child’s age | 6.24 (2.76) | 6.06 (2,83) |

| Household income (BRL) | 4.376 (3.776) | 9.824 (6.722) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Education level | ||

| Elementary school | 31(62) | 18 (36) |

| Higher education | 19 (38) | 32 (64) |

| Marital status | ||

| With partner | 41 (82) | 46 (92) |

| No partner | 9 (18) | 4 (8) |

| Occupation | ||

| Self-employed | 9 (18) | 9 (18) |

| Salaried employee | 15 (30) | 33 (66) |

| Homemaker | 24 (48) | 6 (12) |

| Unemployed | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Children’s Chronic Conditions | ||

| Cerebral palsy | 7 (14) | - |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 21(42) | - |

| Down syndrome | 7 (14) | - |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | 4 (8) | - |

| Sequelae from prematurity | 11 (22) | - |

| Perceived Stress | Mean (Sd) | Estimate | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case | 33.76 (6.07) | 6.2400 | <0.0001 |

| Control | 27.52 (8.09) | Reference | - |

| Variables | Estimate | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Family caregiver’s age | −0.2845 | 0.0098 |

| Household income | −0.0005 | 0.0003 |

| Stressful event | ||

| Yes | 3.9901 | 0.0115 |

| No | Reference | - |

| AUCG–Cortisol | Mean (Sd) | Median | Minimum–Maximum | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0205 | ||||

| Case | 98.14 (45.75) | 87.28 | 39.12–243.60 | |

| Control | 121.41 (70.75) | 105.25 | 46.89–355.50 | |

| Variables | Estimate | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Family caregiver’s age | 0.0030 | 0.0405 |

| Occupation | - | |

| Self-employed | 0.0910 | 0.1178 |

| Salaried employee | 0.0899 | 0.0448 |

| Unemployed | 0.1927 | 0.0598 |

| Homemaker | Reference | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zonta, J.B.; Okido, A.C.C.; de Lima, B.J.; Martins, B.A.; Looman, W.S.; Lopes-Júnior, L.C.; Silva-Rodrigues, F.M.; Lima, R.A.G.d. Stress in Family Caregivers of Children with Chronic Health Conditions: A Case–Control Study. Children 2024, 11, 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111347

Zonta JB, Okido ACC, de Lima BJ, Martins BA, Looman WS, Lopes-Júnior LC, Silva-Rodrigues FM, Lima RAGd. Stress in Family Caregivers of Children with Chronic Health Conditions: A Case–Control Study. Children. 2024; 11(11):1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111347

Chicago/Turabian StyleZonta, Jaqueline Brosso, Aline Cristiane Cavicchioli Okido, Bruna Josiane de Lima, Bianca Annie Martins, Wendy Sue Looman, Luis Carlos Lopes-Júnior, Fernanda Machado Silva-Rodrigues, and Regina Aparecida Garcia de Lima. 2024. "Stress in Family Caregivers of Children with Chronic Health Conditions: A Case–Control Study" Children 11, no. 11: 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111347

APA StyleZonta, J. B., Okido, A. C. C., de Lima, B. J., Martins, B. A., Looman, W. S., Lopes-Júnior, L. C., Silva-Rodrigues, F. M., & Lima, R. A. G. d. (2024). Stress in Family Caregivers of Children with Chronic Health Conditions: A Case–Control Study. Children, 11(11), 1347. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111347