Internalizing Symptoms and Their Impact on Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Fatigue among Patients with Craniopharyngioma During Proton Radiation Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Demographic and Clinical Variables

2.4. Multiple Sleep Latency Test and Actigraphy

2.5. Health-Related Quality of Life, Fatigue, and Socioeconomic Status

2.6. Psychosocial Problems

2.7. Statistical Analysis

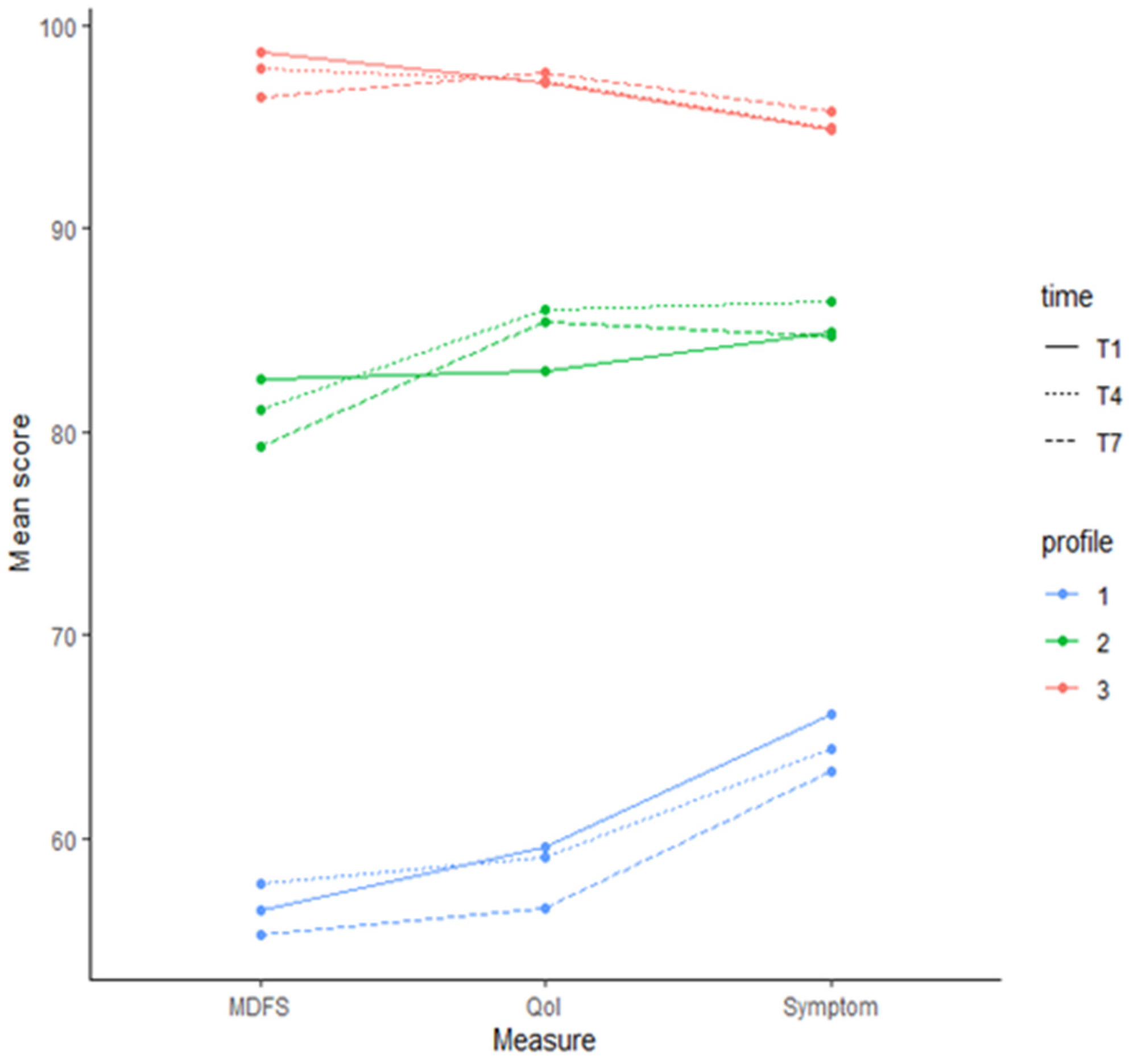

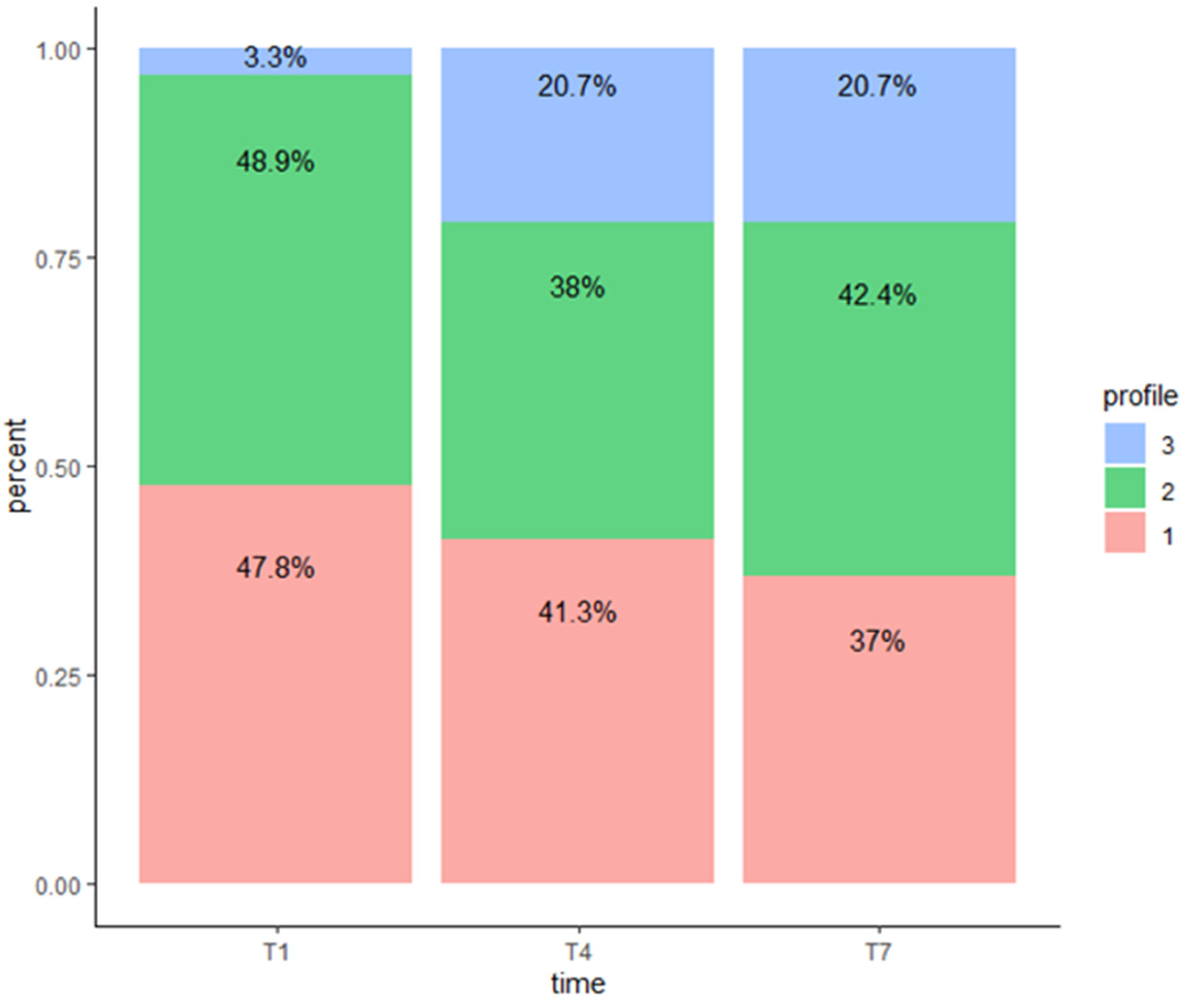

3. Results

Association between Covariates and Profile Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muller, H.L.; Gebhardt, U.; Teske, C.; Faldum, A.; Zwiener, I.; Warmuth-Metz, M.; Pietsch, T.; Pohl, F.; Sorensen, N.; Calaminus, G.; et al. Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: Results of the multinational prospective trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2000 after 3-year follow-up. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 165, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, H.L. Preoperative staging in childhood craniopharyngioma: Standardization as a first step towards improved outcome. Endocrine 2016, 51, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier-Goodnight, A.S.; Ashford, J.M.; Merchant, T.E.; Boop, F.A.; Indelicato, D.J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Conklin, H.M. Neurocognitive functioning in pediatric craniopharyngioma: Performance before treatment with proton therapy. J. Neurooncol. 2017, 134, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrell, B.N.; LaRosa, K.; Hancock, D.; Caples, M.; Sykes, A.; Lu, Z.; Wise, M.S.; Khan, R.B.; Merchant, T.E.; McLaughlin-Crabtree, V. Predictors of narcolepsy and hypersomnia due to medical disorder in pediatric craniopharyngioma. J. Neurooncol. 2020, 148, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, G.; Kintz, N.; Pulido, M.; Amezcua, L. Prevalence of neurobehavioral, social, and emotional dysfunction in patients treated for childhood craniopharyngioma: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poretti, A.; Grotzer, M.A.; Ribi, K.; Schonle, E.; Boltshauser, E. Outcome of craniopharyngioma in children: Long-term complications and quality of life. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2004, 46, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondruch, A.; Maryniak, A.; Kropiwnicki, T.; Roszkowski, M.; Daszkiewicz, P. Cognitive and social functioning in children and adolescents after the removal of craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2011, 27, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klages, K.L.; Berlin, K.S.; Cook, J.L.; Merchant, T.E.; Wise, M.S.; Mandrell, B.N.; Conklin, H.M.; Crabtree, V.M. Health-related quality of life, obesity, fragmented sleep, fatigue, and psychosocial problems among youth with craniopharyngioma. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eveslage, M.; Calaminus, G.; Warmuth-Metz, M.; Kortmann, R.D.; Pohl, F.; Timmermann, B.; Schuhmann, M.U.; Flitsch, J.; Faldum, A.; Muller, H.L. The Postopera tive Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Craniopharyngioma. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2019, 116, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirch, R.; Reaman, G.; Feudtner, C.; Wiener, L.; Schwartz, L.A.; Sung, L.; Wolfe, J. Advancing a comprehensive cancer care agenda for children and their families: Institute of Medicine Workshop highlights and next steps. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Degner, L.F.; Yanofsky, R. A different perspective to approaching cancer symptoms in children. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2003, 26, 800–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B. Chronic pain in childhood and the medical encounter: Professional ventriloquism and hidden voices. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gorp, M.; Irestorm, E.; Twisk, J.W.; Dors, N.; Mavinkurve-Groothuis, A.; Meeteren, A.Y.S.V.; De Bont, J.; van den Bergh, E.M.; van der Meer, W.V.D.P.; Beek, L.R.; et al. The course of health-related quality of life after the diagnosis of childhood cancer: A national cohort study. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jacobs, S.; Dewalt, D.A.; Stern, E.; Gross, H.; Hinds, P.S. A Longitudinal Study of PROMIS Pediatric Symptom Clusters in Children Undergoing Chemotherapy. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyurt, J.; Thiel, C.M.; Lorenzen, A.; Gebhardt, U.; Calaminus, G.; Warmuth-Metz, M.; Muller, H.L. Neuropsychological outcome in patients with childhood craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic involvement. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 876–881.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littner, M.R.; Kushida, C.; Wise, M.; Davila, D.G.; Morgenthaler, T.; Lee-Chiong, T.; Hirshkowitz, M.; Daniel, L.L.; Bailey, D.; Berry, R.B.; et al. Practice parameters for clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test and the maintenance of wakefulness test. Sleep 2005, 28, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozal, D.; Wang, M.; Pope, D.W., Jr. Objective sleepiness measures in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics 2001, 108, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, A. The role and validity of actigraphy in sleep medicine: An update. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Katz, E.R.; Meeske, K.; Dickinson, P. The PedsQL in pediatric cancer: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer 2002, 94, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.N.; Meeske, K.A.; Katz, E.R.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Varni, J.W. The PedsQL Brain Tumor Module: Initial reliability and validity. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2007, 49, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, W. The Baratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMS): Measuring SES; Indiana State University: Haute, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C.R. Behavior assesment system for children-(BASC-2). In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Witcraft, S.M.; Wickenhauser, M.E.; Russell, K.M.; Mandrell, B.N.; Conklin, H.M.; Merchant, T.E.; Crabtree, V.M. A Latent Profile Analysis of Sleep, Anxiety, and Mood in Youth with Craniopharyngioma. Behav. Sleep Med. 2022, 20, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 10.5 (4.0) * |

| Sex | |

| Female | 47 (51.1%) |

| Male | 45(48.9%) |

| Race | |

| White | 59 (64.1%) |

| Black | 16 (17.4%) |

| Asian | 3 (3.3%) |

| Multiple | 9 (9.8%) |

| Other | 3 (3.3%) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.2%) |

| BMI z-score | 1.34 (1.03) |

| Hypothalamic involvement | |

| Grade 0/1 | 37 (40.2%) |

| Grade 2 | 55 (59.8%) |

| Diabetes Insipidus | |

| No | 39 (42.4%) |

| Yes | 53 (57.6%) |

| Narcolepsy | |

| No | 53 (57.6%) |

| Yes | 30 (32.6%) |

| Unknown | 9 (9.8%) |

| Hypersomnia | |

| No | 44 (47.8%) |

| Yes | 39 (42.4%) |

| Unknown | 9 (9.8%) |

| Positive Sleep Diagnosis | |

| No | 14 (15.2%) |

| Yes | 69 (75.0%) |

| Measure | N | Mean (SD) | Median (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 * | |||

| MDFS | 92 | 71 (19) | 71 (3–100) |

| HRQOL | 92 | 72 (16) | 72 (25–100) |

| Symptoms | 92 | 76 (13) | 76 (39–96) |

| T4 * | |||

| MDFS | 80 | 75 (20) | 75 (26–100) |

| HRQOL | 80 | 77 (19) | 77 (26–100) |

| Symptoms | 79 | 79 (15) | 79 (28–100) |

| T7 * | |||

| MDFS | 76 | 74 (21) | 74 (7–100) |

| HRQOL | 76 | 77 (20) | 77 (14–100) |

| Symptoms | 75 | 79 (16) | 79 (28–100) |

| Measure | Change between T1 *, T4 * | pT1 *, T4 * | Change between T4 *, T7 * | pT4 *, T7 * | Change between T1 *, T7 * | pT1 *, T7 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDFS | 6 (−31, 42) | <0.01 | −2 (−44, 39) | 0.55 | 6 (−29, 53) | 0.03 |

| HRQOl | 3 (−26, 33) | 0.04 | 0 (−14, 26) | 0.86 | 3 (−31, 39) | 0.07 |

| Symptom | 7 (−33, 38) | <0.01 | 0 (−24, 28) | 0.92 | 7 (−27, 40) | <0.01 |

| Profile 2 vs. Profile 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 * | T4 * | T7 * | ||||

| Variable | RR (95% CI) | p | RR (95% CI) | p | RR (95% CI) | p |

| BMI z-score | 0.65 (0.37, 1.15) | 0.14 | 0.95 (0.5, 1.8) | 0.87 | 1.11 (0.59, 2.06) | 0.75 |

| Hypersomnia | 1.26 (0.45, 3.47) | 0.66 | 0.49 (0.15, 1.55) | 0.22 | 0.56 (0.18, 1.72) | 0.31 |

| Internalizing prob. | 0.95 (0.91, 1) | 0.05 | 0.93 (0.88, 0.98) | 0.01 | 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) | 0.02 |

| Profile 3 vs. profile 1 | ||||||

| Variable | RR (95% CI) | p | RR (95% CI) | p | RR (95% CI) | p |

| BMI z-score | 1.6 (0.24, 10.66) | 0.63 | 0.62 (0.31, 1.26) | 0.19 | 0.71 (0.35, 1.45) | 0.35 |

| Hypersomnia | 0.97 (0.05, 18.56) | 0.98 | 0.8 (0.21, 3.02) | 0.74 | 0.58 (0.15, 2.21) | 0.42 |

| Internalizing prob. | 0.99 (0.88, 1.1) | 0.82 | 0.96 (0.91, 1.02) | 0.19 | 0.96 (0.9, 1.02) | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mandrell, B.N.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Hancock, D.; Caples, M.; Ashford, J.M.; Merchant, T.E.; Conklin, H.M.; Crabtree, V.M. Internalizing Symptoms and Their Impact on Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Fatigue among Patients with Craniopharyngioma During Proton Radiation Therapy. Children 2024, 11, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11101159

Mandrell BN, Guo Y, Li Y, Hancock D, Caples M, Ashford JM, Merchant TE, Conklin HM, Crabtree VM. Internalizing Symptoms and Their Impact on Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Fatigue among Patients with Craniopharyngioma During Proton Radiation Therapy. Children. 2024; 11(10):1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11101159

Chicago/Turabian StyleMandrell, Belinda N., Yian Guo, Yimei Li, Donna Hancock, Mary Caples, Jason M. Ashford, Thomas E. Merchant, Heather M. Conklin, and Valerie Mc. Crabtree. 2024. "Internalizing Symptoms and Their Impact on Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Fatigue among Patients with Craniopharyngioma During Proton Radiation Therapy" Children 11, no. 10: 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11101159

APA StyleMandrell, B. N., Guo, Y., Li, Y., Hancock, D., Caples, M., Ashford, J. M., Merchant, T. E., Conklin, H. M., & Crabtree, V. M. (2024). Internalizing Symptoms and Their Impact on Patient-Reported Health-Related Quality of Life and Fatigue among Patients with Craniopharyngioma During Proton Radiation Therapy. Children, 11(10), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11101159