Effect of School Bullying on Students’ Peer Cooperation: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. School Bullying and Peer Cooperation

1.2. The Mediating Role of School Belonging

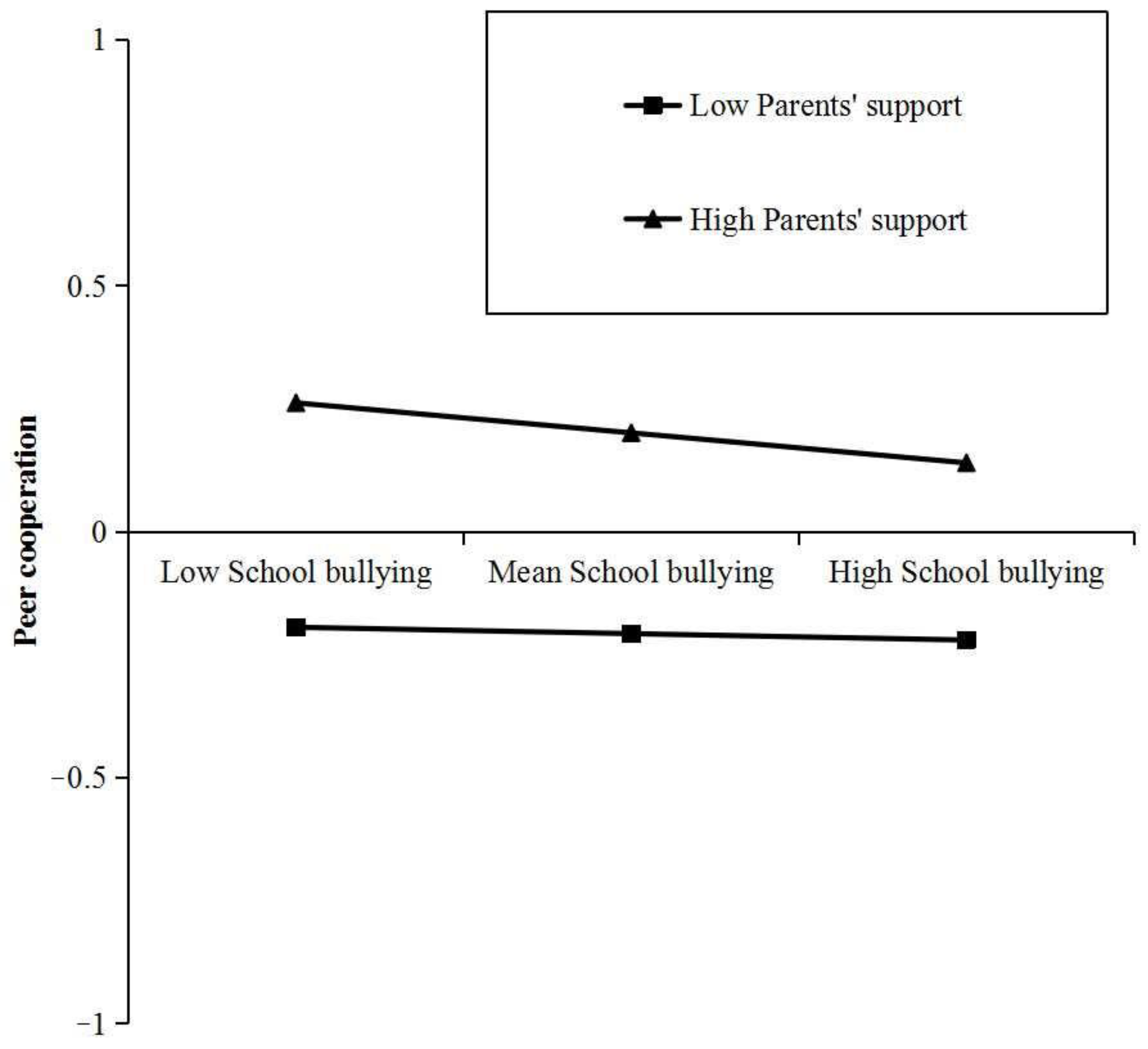

1.3. The Moderating Role of Teacher Support and Parents’ Support

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Research Variables

2.2.1. Peer Cooperation

2.2.2. School Bullying

2.2.3. School Belonging

2.2.4. Teacher Support

2.2.5. Parents’ Support

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Common Method Biases Test

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrices for the Variables

3.2. Moderated Mediation Model Testing

4. Discussion

4.1. The Direct Effect of School Bullying on Peer Cooperation

4.2. The Mediating Role of School Belonging

4.3. The Moderating Role of Teacher Support and Parents’ Support

4.4. Suggestions on the Results

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Overview of PISA and Its Questionnaires

Appendix A.2. Data Collection Methodology

References

- Li, C.H.; Liu, Z.Y. Collaborative problem-solving behavior of 15-year-old Taiwanese students in science education. J. Math. Sci. Techn. Educ. 2017, 13, 6677–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittell, J.H.; Fairfield, K.M.; Bierbaum, B.; Head, W.; Jackson, R.; Kelly, M.; Laskin, R.; Lipson, S.; Siliski, J.; Zuckerman, T.J. Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and functioning, and length of stay: A nine-hospital study of surgical patients. Med. Care 2000, 38, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, J. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.; Groves, W. Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 94, 774–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.C.; Cui, R.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the world economy and response from the perspective of the community with a shared future for mankind. Area Study Glob. Dev. 2020, 6, 5–22+155. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures on achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 89, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseth, C.J.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T. Promoting early adolescents’ achievement and peer relationships: The effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosnoe, R.; Johnson, M.; Kirkpatrick, E., Jr.; Glen, H. Intergenerational bonding in school: The behavioral and contextual correlates of student-teacher relationship. Sociol. Educ. 2004, 77, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Kwok, O. Influence of student–teacher and parent–teacher relationships on lower achieving readers’ engagement and achievement in the primary grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.; Greenberg, M. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, R.; Rehman, M.; Wang, K.S.; Hashmani, M.A.; Shamim, A. Investigation of knowledge sharing behavior in global software development organizations using social cognitive theory. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 71286–71298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, T.M.; Brezina, T.; Crank, B.R. Agency, self-efficacy, and desistance from crime: An application of social cognitive theory. J. Dev. Life-Course Cr. 2019, 5, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, W. A review on cooperative behaviors from a perspective of social cognition theory. Psychol. Commun. 2020, 3, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Kou, Y. The developmental characteristics of four typical prosocial behaviors of children. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2006, 1, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bully/victim problems among schoolchildren: Long-term consequences and an effective intervention program. Prospects 1993, 26, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Nansel, T.R. School bullying among adolescents in the united states: Physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. J. Adolescent Health 2009, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awiria, O.; Olweus, D.; Byrne, B. Bullying at school-What we know and what we can do. Brit. J. Educ. Stud. 1994, 42, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. J. Child Psychol. Psych. All. Disc. 1994, 35, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Morita, Y.; Junger-Tas, J. The Nature of School Bullying: A Cross National Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wolke, D.; Lereya, T. Long-term effects of bullying. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochel, K.; Ladd, G.; Rudolph, K. Longitudinal associations among youth depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and low peer acceptance: An interpersonal process perspective. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, J.; Derrick, J.; Wang, W.; Testa, M.; Nickerson, A.; Espelage, D.; Miller, K. Proximal associations among bullying, mood, and substance use: A daily report study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2558–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigby, K.; Cox, I. The contributions of bullying and low self-esteem to acts of delinquency among Australian teenagers. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 1996, 21, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fante, C. Fenômeno Bullying: Como Prevenir a Violência Nas Escolas e Educar Para Paz [Bullying Phenomenon: How to Prevent Violence in Schools and Educate for Peace]; Verus editora: Campinas, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, A. Bullying: Comportamento agressivo entre estudantes [Bullying: Aggressive behavior among students]. J. Pediatr. 2005, 81, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponzo, M. Does bullying reduce educational achievement? An evaluation using matching estimators. J. Policy Model. 2013, 35, 1057–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L. Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 106, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, R.; Felmlee, D. Casualties of social combat: School networks of peer victimization and their consequences. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 79, 228–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Chen, N.; Xuan, H. An empirical study on the peer relationship and school bullying of students in rural boarding junior middle school. Educ. Res. Exp. 2019, 2, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.Y. The Influence of Peer Relationship and Self-Esteem on School Bullying of Junior Students and Intervention Research. Master’s Thesis, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.R. The Relationship between Junior High School Students’ Peer Relationship, Moral Disengagement, and Bystander Behavior in Campus Bullying. Master’s Thesis, Xinjiang Normal University, Urumqi, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.M. A Study and Intervention on the Relationship of Emotional Intelligence, Peer Relations, and Campus Bullying of Junior High School Students. Master’s Thesis, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H. The Influence and Intervention of Peer Relationship of Junior High School Students on Being Bullied. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L. A Study on the Relationship among Middle School Students’ Peer Relationship, School Belonging, and Campus Bullying. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Q. The influence of teacher support on 15-year-old students’ positive emotions-The mediating role of school belonging. J. Shanghai Educ. Res. 2020, 7, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, T.W.; Wampold, B.E.; Quintana, S.M.; Enright, R.D. Belongingness as a protective factor against loneliness and potential depression in a multicultural middle school. Couns. Psychol. 2010, 38, 626–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.R.; Guo, T.F.; Wang, M.H. Relationship between teacher support and general self-efficacy of the children affected by hiv/aids: The mediating effect of school belonging. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 26, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Q.; Zhao, B.H. The effect of teachers’ support on the bullying of the 4th–9th graders: The mediating effect of school belonging. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2019, 1, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Zhi, T.J. The influencing factors and long-term mechanism of bullying prevention in schools: Analysis on bullying behavior of adolescent in 2015. Res. Educ. Dev. 2017, 20, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, D.C. The impact assessment of school bullying on students’ educational performance—Evidence from PISA 2015 Beijing-Shanghai-Jiangsu-Guangdong (China). Educ. Econ. 2020, 36, 31–41+53. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhao, D.C. School bullying in middle school: Current status, impacts and coping strategies-Research based on China’s four provinces (cities) and OECD country data. Mod. Educ. Manag. 2018, 12, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldweber, A.; Waasdorp, T.E.; Bradshaw, C.P. Examining the link between forms of bullying behaviors and perceptions of safety and belonging among secondary school students. J. School Psychol. 2013, 51, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, I.; Reynolds, K., Jr.; Lee, E.; Subasic, E.; Bromhead, D. Well-being, school climate, and the social identity process: A latent growth model study of bullying perpetration and peer victimization. School Psychol. Quart. 2014, 29, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C. Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. J. Early Adolesc. 1993, 13, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C.; Grady, K.E. The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. J. Exp. Educ. 1993, 62, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Social Identity Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, B.C.; Eswaran, M.; Oxoby, R.J. ‘Us’ and ‘Them’: The origin of identity, and its economic implications. Can. J. Econ. 2011, 44, 719–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A.I. Can good projects succeed in bad communities? J. Public Econ. 2009, 93, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cremer, D. Respect and cooperation in social dilemmas: The importance of feeling included. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B. 2002, 28, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Developmental Psychology, 2nd ed.; People’s Education Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, G.E.; Hickman, C.W. Research and practice in parent involvement: Implications for teacher education. Elem. School J. 1991, 91, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. A Study on School Bullying Behavior of x Middle School Students: Based on the Perspective of Social Support theory. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A.S.; McInerney, D.M. Students’perceived support from teachers: Impacts on academic achievement, interest in schoolwork, attendance, and self-esteem. Acad. Ach. 1999, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, D. A Study on the Relationship between Teacher Expectation, Academic Self-Concept, Students’ Perception of Teacher Support Behavior and Academic Achievement. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Demaray, M.K.; Malecki, C.K.; Davidson, L.M.; Hodgson, K.K.; Rebus, P.J. The relationship between social support and student adjustment: A longitudinal analysis. Psychol. Schools. 2010, 42, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, R.; Leadbeater, B. Adults make a difference: The protective effects of parent and teacher emotional support on emotional and behavioral problems of peer-victimized adolescents. J. Community. Psychol. 2010, 38, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Swearer, S.M.; Lembeck, P.; Collins, A.; Berry, B. Teachers matter: An examination of student-teacher relationships, attitudes toward bullying, and bullying behavior. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2015, 31, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Yang, J.; Xu, S. An empirical study on deviant behaviors and bullying victimization among children from social bonding perspective. Chin. J. School Health 2019, 40, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Yu, C.F.; Zhao, C.H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. The mediating role of school belonging between the school atmosphere and the academic performance of left-behind children. Chin. J. School Health 2016, 7, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María, C.; Eva, E.-C.; Esther, L.-M.; Luis, L.; Enrique, N.-A.; José, L.G. Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 14, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Kong, R.; Chen, X.; Xue, H. The cooperative tendencies of children and the job values of their parents. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 23, 699–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L. Review of the research on children’s cooperative behavior. Stud. Presch. Educ. 2010, 4, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.-C.; Gefen, D. Validation guidelines for IS positivist research. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Sys. 2004, 13, 380–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, B.S.; Straub, D.W.; Rai, A. Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Quart. 2007, 31, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Long, L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 12, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: Competitors or backups? Act. Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Kelley, K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, D.; Gregory, A.; Huang, F.; Fan, X.T. Perceived prevalence of teasing and bullying predicts high school dropout rates. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J. Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch. Suicide Res. 2010, 14, 206–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M.K.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.M.; Polanin, J.R.; Holland, K.M.; DeGue, S.; Matjasko, J.L.; Wolfe, M.; Reid, G. Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, D.; Boulton, M. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J. Child. Psychol. Psych. All. Discip. 2000, 41, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, D.S.; van der Ven, E.; Velthorst, E.; Selten, J.-P.; Morgan, C.; de Haan, L. Childhood bullying and the association with psychosis in non-clinical and clinical samples: A review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2012, 42, 2463–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P.; Lösel, F.; Loeber, R. Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Aggress. Confl. Peac. 2011, 3, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, M.; Goemans, A.; Vedder, H. The relation between peer victimization and sleeping problems: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 27, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H. The effect of school climate on secondary school students’ learning engagement: The mediating effect of school well-being. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2017, 4, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H. The effect of school climate on migrant children’ learning engagement: The mediating role of school well-being. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2018, 1, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.J.; Yang, W.J. The development of different types of internet addiction scale for undergraduates. Chin. J. Ment. Health 2006, 20, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social ties and mental health. J. Urban Health 2018, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.F.; Xie, Y.T. Effect of problematic internet use on suicidal ideation among junior middle school students: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Dev. Educ. 2019, 35, 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.R. Bullying among middle school students in China: A comparative study of Mainland China, Hong Kong and Macao. Chin. Youth Study 2020, 10, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, A.B.; Bowen, G.L. Teacher support and the school engagement of Latino middle and high school students at risk of school failure. Child Adolesc. Soc.Work. 2004, 21, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Parent-child relationship and parent-child communication. Educ. Res. 2001, 6, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; Shen, S. The relationship between family capital and school bullying in junior high school. Search 2018, 5, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.L. Prestige stratification in contemporary Chinese society: Measurement of occupational prestige and socioeconomic status index. Sociol. Res. 2015, 2, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.M.; Du, M.J. The influence of spoiling for children’s mental health. Educ. Teach. Forum. 2017, 3, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L. A review of research on influencing factors of cooperative behavior of children abroad. Foreign Prim. Sec. Educ. 2010, 12, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Chen, I.-H. Multilevel analysis of factors influencing school bullying in 15-year-old students. Children 2023, 10, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Peer cooperation | 11.388 | 2.767 | 1 | ||||

| 2. School bullying | 7.604 | 2.931 | −0.171 ** | 1 | |||

| 3. School belonging | 17.716 | 3.297 | 0.404 ** | −0.333 ** | 1 | ||

| 4. Teacher support | 13.576 | 2.769 | 0.286 ** | −0.175 ** | 0.246 ** | 1 | |

| 5. Parents’ support | 9.990 | 1.929 | 0.304 ** | −0.144 ** | 0.286 ** | 0.202 ** | 1 |

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | |||||||

| Peer cooperation | (constant) | 12.767 | 0.078 | 162.843 | <0.001 | 12.614 | 12.921 |

| School bullying | −0.181 | 0.010 | −18.660 | <0.001 | −0.200 | −0.162 | |

| Direct effect | |||||||

| (constant) | 5.603 | 0.181 | 31.027 | <0.001 | 5.249 | 5.957 | |

| Peer cooperation | School bullying | −0.043 | 0.010 | −4.546 | <0.001 | −0.062 | −0.025 |

| Indirect effect | |||||||

| School belonging | (constant) | 20.752 | 0.085 | 245.205 | <0.001 | 20.586 | 20.918 |

| School bullying | −0.399 | 0.010 | −38.064 | <0.001 | −0.419 | −0.378 | |

| Peer cooperation | (constant) | 5.603 | 0.181 | 31.027 | <0.001 | 5.249 | 5.957 |

| School belonging | 0.345 | 0.008 | 43.355 | <0.001 | 0.330 | 0.361 | |

| Effect | Boot SE | t | p | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||

| Peer cooperation | School bullying | −0.138 | 0.006 | / | / | −0.149 | −0.127 |

| Ratio of indirect to total effect of School bullying on Peer cooperation | |||||||

| School belonging | 0.760 | 0.051 | / | / | 0.673 | 0.876 | |

| R-squared mediation effect size (R-sq_med) | |||||||

| School belonging | 0.028 | 0.003 | / | / | 0.022 | 0.033 | |

| Preacher and Kelley (2011) Kappa-squared | |||||||

| School belonging | 0.128 | 0.005 | / | / | 0.118 | 0.138 | |

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | R2 | F | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School belonging | (constant) | 0.149 | 677.969 | −0.005 | 0.009 | −0.593 | 0.553 | −0.022 | 0.012 |

| School bullying | −0.311 | 0.009 | −34.143 | <0.001 | −0.329 | −0.293 | |||

| Teacher support | 0.200 | 0.009 | 22.782 | <0.001 | 0.183 | 0.217 | |||

| School bullying × Teacher support | −0.032 | 0.007 | −4.508 | <0.001 | −0.046 | −0.018 | |||

| Peer cooperation | (constant) | 0.164 | 1138.785 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.976 | −0.016 | 0.017 |

| School bullying | −0.041 | 0.009 | −4.586 | <0.001 | −0.059 | −0.024 | |||

| School belonging | 0.388 | 0.009 | 43.270 | <0.001 | 0.370 | 0.406 | |||

| Conditional indirect effect at specific levels of the moderator | |||||||||

| Moderator: level of Teacher support | β | Boot SE | t | p | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||

| M − SD | −0.108 | 0.006 | / | / | −0.119 | −0.097 | |||

| Mean | −0.121 | 0.005 | / | / | −0.131 | −0.110 | |||

| M + SD | −0.131 | 0.007 | / | / | −0.145 | −0.118 | |||

| Index of moderated mediation | |||||||||

| Index | Boot SE | t | p | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| Teacher support | −0.012 | 0.003 | / | / | −0.019 | −0.006 | |||

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | R2 | F | β | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School belonging | (constant) | 0.110 | 1442.695 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.051 | 0.960 | −0.017 | 0.018 |

| School bullying | −0.334 | 0.009 | −37.983 | <0.001 | −0.352 | −0.317 | |||

| Peer cooperation | (constant) | 0.201 | 732.234 | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.394 | 0.693 | −0.02 | 0.013 |

| School bullying | −0.037 | 0.009 | −4.117 | <0.001 | −0.055 | −0.02 | |||

| School belonging | 0.333 | 0.009 | 36.661 | <0.001 | 0.315 | 0.35 | |||

| Parents’ support | 0.204 | 0.009 | 23.489 | <0.001 | 0.187 | 0.221 | |||

| School bullying × Parents’ support | −0.024 | 0.007 | −3.525 | <0.001 | −0.038 | −0.011 | |||

| Indirect effect of School bullying on Peer cooperation | |||||||||

| Index | Boot SE | t | p | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||

| School belonging | −0.111 | 0.005 | / | / | −0.121 | −0.102 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.-J.; Chen, I.-H. Effect of School Bullying on Students’ Peer Cooperation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Children 2024, 11, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010011

Wang Y-J, Chen I-H. Effect of School Bullying on Students’ Peer Cooperation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Children. 2024; 11(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu-Jiao, and I-Hua Chen. 2024. "Effect of School Bullying on Students’ Peer Cooperation: A Moderated Mediation Model" Children 11, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010011

APA StyleWang, Y.-J., & Chen, I.-H. (2024). Effect of School Bullying on Students’ Peer Cooperation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Children, 11(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010011