The Difference in the Creativity of People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Those with Typical Hearing: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Concept

2.2.3. Context

2.3. Types of Sources of Evidence

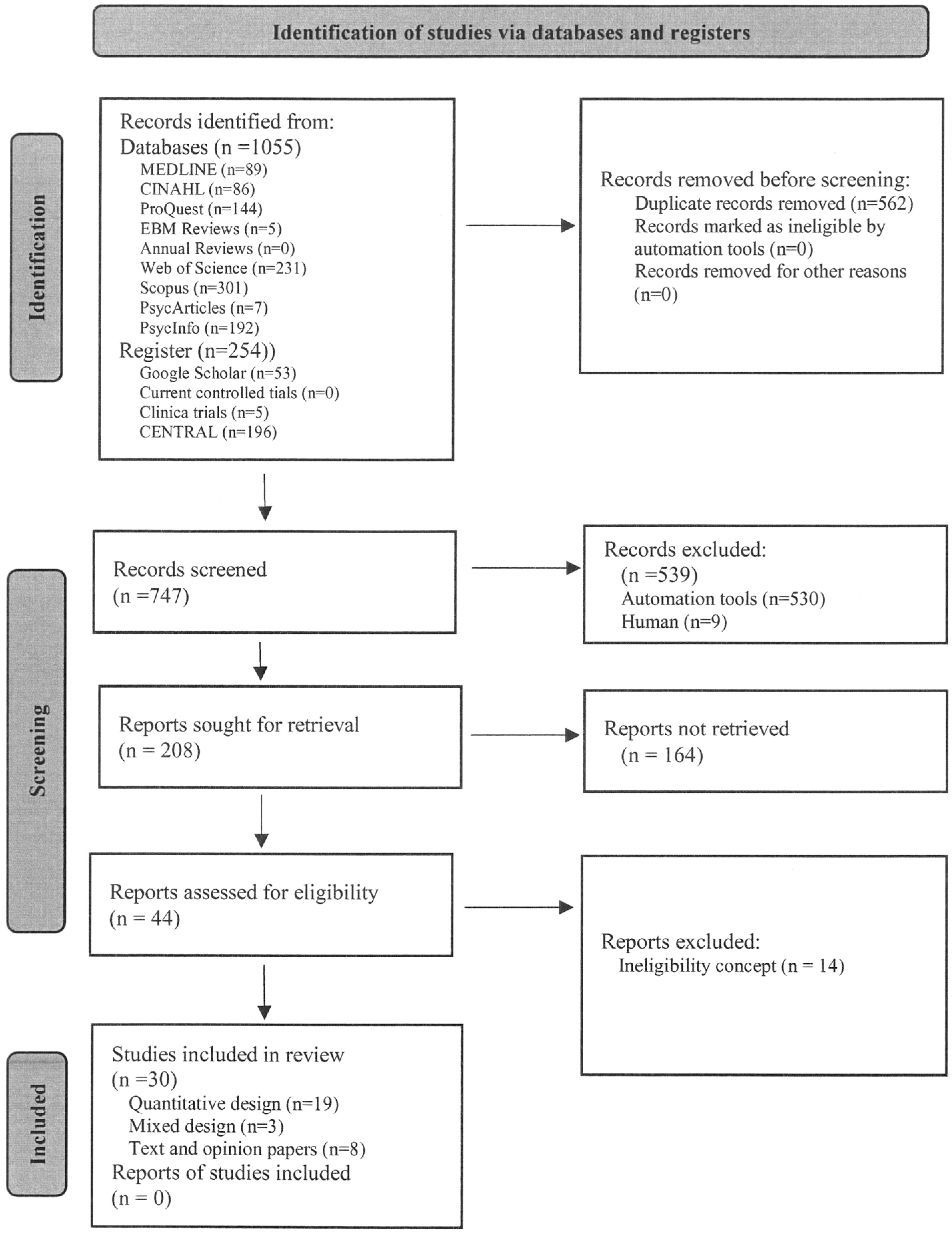

2.4. Methods

- Search strategy

- Source of evidence screening and selection

- Data extraction

- Analysis and presentation of results

2.4.1. Search Strategy

2.4.2. Screening and Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.4.3. Data Extraction

- General study details (authors, publication date, country, respondents);

- Methodology (characteristics of creativity, study design, tools, area of interest, and study aim);

- Output (1. description of creativity; 2. possibilities of development of creativity; 3. differences between DHH and TH, internal validity and reliability of tools developed) and verifiability of research and tools.

2.4.4. Analysis and Presentation of Results

3. Results

3.1. General Study Details

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Characteristics of Creativity

3.2.2. Study Design

Quantitative Design

Mixed Design

Text and Opinion Studies

3.2.3. Outputs

- Description of creativity,

- Development of creativity,

- Differences in creativity between HDD and TH people.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Studies Included

4.2. Limitations and Strengths of This Scoping Review

5. Conclusions

6. Implication for Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Batey, M.; Furnham, A. Creativity, intelligence, and personality: A critical review of the scattered literature. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2006, 132, 355–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nettle, D. Strong Imagination: Madness, Creativity, and Human Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hennessey, B.A.; Amabile, T.M. Creativity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, A.; Benedek, M.; Grabner, R.H.; Staudt, B.; Neubauer, A.C. Creativity Meets Neuroscience: Experimental Tasks for the Neuroscientific Study of Creative Thinking. Methods 2007, 42, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hensley, N. Educating for Sustainable Development: Cultivating Creativity through Mindfulness. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J.P. Transformation abilities of functions. J. Creat. Behav. 1983, 17, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pillemer, J. Perspectives on the Social Psychology of Creativity. J. Creat. Behav. 2012, 46, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingölbali, E.; Bingölbali, F. Divergent thinking and convergent thinking: Are they promoted in mathematics textbooks? Int. J. Contemp. Educ. Res. 2020, 7, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauk, E.; Benedek, M.; Dunst, B.; Neubauer, A.C. The Relationship between Intelligence and Creativity: New Support for the Threshold Hypothesis by Means of Empirical Breakpoint Detection. Intelligence 2013, 41, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potmesil, M.; Potmesilova, P.; Horakova, R.; Groma, M. Psychosociální Aspekty Sluchového Postižení; Masarykova Univerzita: Brno, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott, C.; Looney, D.; Martin, S. Social Work with Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Sch. Soc. Work J. 2012, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lampropoulou, V. The Education of Deaf Children in Greece. In Deaf People Around the World: Educational and Social Perspectives; Moores, D.F., Miller, M.S., Eds.; Gallaudet University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardin, J.L. Family Empowerment: Supporting Language Development in Young Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. Volta Rev. 2006, 106, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Deafness and Hearing Loss: Fact Sheet No. 300. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- van der Straaten, T.F.K.; Rieffe, C.; Soede, W.; Netten, A.P.; Dirks, E.; Oudesluys-Murphy, A.M.; Dekker, F.W.; Böhringer, S.; Frijns, J.H.M. Quality of Life of Children with Hearing Loss in Special and Mainstream Education: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 128, 109701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanović, S.; Živković, J. Working with pupils with hearing impairments in an inclusive education: Characteristics and competences. Hum. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2020, 10, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa, O.M.A.; Angulo, L.M.V. Children with Hearing Loss Health-Related Quality of Life and Parental Perceptions. Int. Educ. Stud. 2020, 13, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marschark, M.; Shaver, D.M.; Nagle, K.M.; Newman, L.A. Predicting the Academic Achievement of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students from Individual, Household, Communication, and Educational Factors. Except. Child. 2015, 81, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.-Y.; Guthridge, S.; He, V.Y.; Howard, D.; Leach, A.J. The Impact of Hearing Impairment on Early Academic Achievement in Aboriginal Children Living in Remote Australia: A Data Linkage Study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, S.; Cordes, S. Math abilities in deaf and hard of hearing children: The role of language in developing number concepts. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 129, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschark, M.; Spencer, P.E.; Adams, J.; Sapere, P. Evidence-based Practice in Educating Deaf and Hard-Of-Hearing Children: Teaching to Their Cognitive Strengths and Needs. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2011, 26, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, C.M.; Perez, S.M.; Lederberg, A.R. Assessing Aspects of Creativity in Deaf and Hearing High School Students. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2013, 18, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What Kind of Systematic Review Should I Conduct? A Proposed Typology and Guidance for Systematic Reviewers in the Medical and Health Sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Trico, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 4 January 2023).

- Potmesilova, P.; Potmesil, M.; Klugar, M. Differences between the creativity of people who are deaf or hard of hearing and those with typical hearing: A protocol for the further scoping review. Creat. Stud. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; Porritt, K.; Farrow, J.; Lockwood, C.; Stephenson, M.; Moola, S.; Lizarondo, L.; et al. The Development of Software to Support Multiple Systematic Review Types: The Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). JBI Evid. Implement. 2019, 17, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpin, G.; Torrance, E.P. Comparison of Creative Thinking Abilities of Blind and Deaf Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1973, 37, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnidha, Y.; Hidayatulloh. Mathematical Representation of Deaf Students in Problem Solving Seen from Students’ Creative Thinking Levels. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1155, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daramola, D.S.; Bello, M.B.; Yusuf, A.R.; Amali, I.O.O. Creativity Level of Hearing Impaired and Hearing Students of Federal College of Education. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 1489–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.G. Utilization of Creative Drama with Hearing-Impaired Youth. Volta Rev. 1984, 86, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, F.A. Assessing Creative Thinking Abilities of Deaf Children. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2006, 21, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, F. Comparing Creative Thinking Abilities and Reasoning Ability of Deaf and Hearing Children. Roeper Rev. A J. Gift. Educ. 2006, 28, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.S. A Comparative Study of the Most Creative and Least Creative Student in Grades 4–8 at the Boston School for the Deaf, Randolph, Massachusetts; Boston College: Chestnut Hill, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, A.C. A Comparative Study of the Creative Expressions in Paint and Clay of Deaf and Hearing Children. In Independent Studies and Capstones; Program in Audiology and Communication Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1942; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.A.; Khatena, J. Comparative Study of Verbal Originality in Deaf and Hearing Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1975, 40, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A. Creative Thinking in the Absence of Language: Deaf versus Hearing Adolescents. Child Study J. 1977, 7, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltsounis, B. Impact of Instruction on Development of Deaf Children’s Originality of Thinking. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1969, 29, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsounis, B. Comparative Study of Creativity in Deaf and Hearing Children. Child Study J. 1970, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltsounis, B. Differences in Verbal Creative Thinking Abilities between Deaf and Hearing Children. Psychol. Rep. 1970, 26, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltsounis, B. Differences in Creative Thinking of Black and White Deaf Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1971, 32, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughton, J. Strategies for Developing Creative Abilities of Hearing-Impaired Children. Am. Ann. Deaf 1988, 133, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubin, E.; Sherrill, C. Motor Creativity of Preschool Deaf Children. Am. Ann. Deaf 1980, 125, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschark, M.; Clark, D. Linguistic and Nonlinguistic Creativity of Deaf Children. Dev. Rev. 1987, 7, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschark, M.; Everhart, V.S.; Martin, J.; West, S.A. Identifying Linguistic Creativity in Deaf and Hearing Children. Metaphor. Symb. Act. 1987, 2, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschark, M.; West, S.A. Creative Language Abilities of Deaf Children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1985, 28, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschark, M.; West, S.A.; Nall, L.; Everhart, V. Development of Creative Language Devices in Signed and Oral Production. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1986, 41, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarsih, N.M.M.; Wahab, R. The Influence of Role Art Learning for Improvement Creativity (Improvisation, Expression and Gesture) Deaf Students at SLB Marganingsih Yogyakarta; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Moorjhani, J.D.; Jacob, E.A.; Nathawat, S.S. A Comparative Study of Intelligence and Creativity in Hearing Impaired and Normal Boys and Girls. Indian J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 25, 200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, H.; Horrocks, C. An Exploratory Study of Creativity in Deaf Children. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1968, 27, 844–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paszkowska-Rogacz, A. Nonverbal Aspects of Creative Thinking: Studies of Deaf Children. Eur. J. High Abil. 1992, 3, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, R.; Sherrill, C. Creative Thinking and Dance/Movement Skills of Hearing-Impaired Youth: An Experimental Study. Am. Ann. Deaf 1981, 126, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silver, R.A. The Question of Imagination, Originality, and Abstract Thinking by Deaf Children. Am. Ann. Deaf 1977, 122, 349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Szobiová, E.; Zborteková, K. Logické Uvažovanie, Vizuálno-Priestorová Predstavivosť a Tvorivé Vnímanie Adolescentov so Sluchovým Postihnutím = Logical Reasoning, Visual-Spatial Imagination, and Creative Perception of Adolescents with Hearing-Impairment. Psychológia A Patopsychológia Dieťaťa 2006, 41, 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Sun, Y.-J.; Yan, N.; Lin, Y.; Li, Q.; Wan, S.-Y.; Xun, M.-M. Creative Thinking of Deaf Children and Its Related Factors. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2009, 23, 824–827. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, E.P. Creativity and Its Educational Implications for the Gifted. Gift. Child Q. 1968, 12, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J.P. The Nature of Human Intelligence; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, W.J.; McGrew, K.S. The Cattell–Horn–Carroll Theory of Cognitive Abilities. In Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 73–163. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, P.J.; Beaty, R.E. Making Creative Metaphors: The Importance of Fluid Intelligence for Creative Thought. Intelligence 2012, 40, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Sin, K.F. Thinking Styles and Self-Determination among University Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Hearing University Students. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 85, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.C.J. A review of the perceptual effects of hearing loss for frequencies above 3 kHz. Int. J. Audiol. 2016, 55, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megreya, A.M.; Bindemann, M. A visual processing advantage for young-adolescent deaf observers: Evidence from face and object matching tasks. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlin, T.; Hiddinga, A. Technological socialities: The impact of information and communication technologies on belonging among deaf and hard-of-hearing people. Sociol. Compass 2023, 17, e13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsić, R. Deaf persons and visual art. Knowl. Int. J. 2017, 17, 1671–1675. Available online: https://ikm.mk/ojs/index.php/kij/article/view/4136 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Berselli, M.; Lulkin, S.A. Theatre and dance with deaf students: Researching performance practices in a Brazilian school context. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 2017, 22, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besançon, M.; Lubart, T. Differences in the Development of Creative Competencies in Children Schooled in Diverse Learning Environments. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2008, 18, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliotti, N.C.; Blanton, W.E. Creative Thinking Ability, School Readiness, and Intelligence in First Grade Children. J. Psychol. 1973, 84, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A. The Relationship between School Achievement and Creativity at Different Educational Stages. Think. Ski. Creat. 2016, 19, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcus, A.; Tuomainen, O.; Campos, A.; Rosen, S.; Halliday, L.F. Functional brain alterations following mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss in children. eLife 2019, 8, e46965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Cancer, A.; Carruthers, L.; Antonietti, A. Editorial: Creativity in Pathological Brain Conditions across the Lifespan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 932399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanova, T.G.; Morgacheva, E.N.; Popova, T.M.; Sokolova, O.Y.; Tjurina, N.S. Creativity and creative work in children with disabilities. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 117, 01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekkedal, A.M. Assistive Hearing Technologies among Students with Hearing Impairment: Factors That Promote Satisfaction. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2012, 17, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors and Publication Date | Country | Respondents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number N (DHH) | Gender | Age | Characteristic of DHH | ||

| Arnidha and Hidayatulloh, 2019 [29] | Indonesia | 5 | NS | fifth grade | deaf |

| Daramola et al., 2019 [30] | Nigeria | 248 (146) | NS | second year | NS |

| Davies, 1984 [31] | United States of Amerika | NS | NS | NS | Hearing-impaired |

| Ebrahim, 2006 [32] | United States of Amerika | 410 (210) | NS | 8–11 y | Hear loss 90–131 dB |

| Ebrahim, 2006 [33] | United States of Amerika | 410 (210) | NS | 8–11 y | Hear loss 90–131 dB |

| Gallagher, 1968 [34] * | United States of Amerika | 74 | Boys 34 Girls 40 | 4th–8th grades | deaf |

| Halpin and Torrance, 1973 [28] | United States of Amerika | 68 (34) | NS | 9–11 y | Hearing deprivation was substantial enough to prevent them from making satisfactory progress in public schools. |

| Hicks, 1942 [35] * | United States of Amerika | 8 (8) | Boys 4 Girls 4 | 5 y 11 m–8 y 9 m | deaf |

| Johnson, 1975 [36] | United States of Amerika | 182 | Males 90 Females 92 | 10–19 y | Profoundly deaf; not benefit from hearing aids. |

| Johnson, 1977 [37] | United States of Amerika | 133 (133) | Males 68 Females 65 | 11–19 y | deaf—not benefiting from hearing aids |

| Johnson and Khatena, 1975 [36] | United States of Amerika | 417 (181) | Males 89 Females 92 | 10–19 y | profoundly deaf, i.e., they did not benefit from hearing aids |

| Kaltsounis, 1969 [38] | United States of Amerika | 35 | NS | second grade | deaf |

| Kaltsounis, 1970 [39] | United States of Amerika | 777 (172) | NS | 1st–6th grades | Deaf–hearing deprivation was substantial enough |

| Kaltsounis, 1970 [40] | United States of Amerika | 418 (67) | NS | 4th–6th grades | hearing deprivation was substantial enough to prevent them from making satisfactory progress in public schools |

| Kaltsounis, 1971 [41] | United States of Amerika | 233 | Boys 114 Girls 119 | 1st–4th grades | deaf |

| Laughton, 1988 [42] | United States of Amerika | 28 | Male 14 Female 14 | 8–10 y | 85 dB loss or greater |

| Lubin and Sherrill, 1980 [43] | United States of Amerika | 24 (12) | Boys 7 Girls 5 | 3–5 y | hearing loss (moderate, severe, profound) |

| Marschark and Clark, 1987 [44] | United States of Amerika | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Marschark et al., 1987 [45] | United States of Amerika | NS | NS | NS | deaf |

| Marschark and West, 1985 [46] | United States of Amerika | 8 (4) | Boys 3 Girl 1 | 12.10–15.0 y | ≥80 dB |

| Marschark et al., 1986 [47] | United States of Amerika | 40 (20) | Male 11 Female 9 | 8.1–14.8 y | deaf |

| Minarsih and Wahab, 2019 [48] * | Indonesia | 1 | NS | high school | deaf |

| Moorjhani et al., 1998 [49] | Rajasthan | 80 (NS) | NS | 6–11 y | from 55 dB to 89 dB |

| Pang and Horrocks, 1968 [50] | United States of Amerika | NS (11) | Boys 6 Girls 5 | 11–12 y | deaf |

| Paszkowska-Rogacz, 1992 [51] | Poland | 44 (22) | Boys 10 Girls 12 | 13–15 y | deaf |

| Reber and Sherrill, 1981 [52] | United States of Amerika | 10 | Male 8 Female 2 | 9–14 y | 71–90 dB 4 90 dB + 6 |

| Silver, 1977 [53] | United States of Amerika | 44 (22) | NS | NS | deaf |

| Stanzione et al., 2013 [22] | United States of Amerika | 52 (17) | Male 10 Female 7 | 14–18 y | CI 3 hearing aids 14 |

| Szobiová and Zborteková, 2006 [54] | Slovakia | 69 (45) | Male 18 Female 27 | 18–88 y | NS |

| Yu et al., 2009 [55] * | People’s Republic of China | 144 (122) | Male 62 Female 60 | 8–16 | deaf |

| Study Design | Statistical Methods Used | Aim | Tools | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daramola et al., 2019 [30] | Case series | Split half, Cronbach’s Alpha, Spearman-Brown correlation | Difference between DHH and TH | a tool created by the authors Questionnaire on the Creativity Level of Students with Hearing- impaired and Hearing |

| Ebrahim, 2006 [32] | Case series | Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking-Figural, Form A (A1-3) |

| Ebrahim, 2006 [33] | Case series | Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking-Figural, Form A (A1-3) |

| Gallagher, 1968 [34] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Split half and Kuder-Richardson coefficient of reliability | The relationship between Creativity thinking and IQ | The Abbreviated Form VII, Minnesota Tests of Creative Thinking. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales |

| Johnson, 1975 [36] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Factor analysis | The relationship between creativity and onomatopoeic words | Onomatopoeia and Images, Form lB |

| Johnson, 1977 [37] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Analysis of variance (ANOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH + intellectual function | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking—Figural Form B; |

| Johnson and Khatena, 1975 [36] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | F-test, correlation | Difference between DHH and TH | Onomatopoeia and Images, Form 1B |

| Kaltsounis, 1970 [39] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Analysis of variance (ANOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking-Figural, Form A |

| Kaltsounis, 1970 [40] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Three two-way factorial analyses | Difference between DHH and TH | Torrance Test of Thinking Creatively With Words, Form A |

| Kaltsounis, 1971 [41] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Two-way factor analysis | Level of creativity of DHH | Torrance Test of Thinking Creatively With Pictures, Form A (1966) |

| Laughton, 1988 [42] | Before and after studies | Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) | Influence of creativity + two curricular designs | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking |

| Lubin and Sherrill, 1980 [43] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH + motor creativity | Torrance Tests of Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement |

| Pang and Horrocks, 1968 [50] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Analysis of variance (ANOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH + intellect | Raven’s Coloured Progressive Matrices, Wallach and Kogan Creativity Test; |

| Paszkowska-Rogacz, 1992 [51] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Medium values, standard deviation | Difference between DHH and TH | Barron–Welsh Art Scale, Torrance’s Tests of Creative Thinking, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children |

| Reber and Sherrill, 1981 [52] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Pearson correlation, Student’s t-test and frequency analysis | Difference between DHH and TH + classroom behavior | The Test for Creative Thinking–Drawing Production; Raven’s Progressive Matrices test; Pupil Behavior Inventory |

| Stanzione et al., 2013 [22] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Test-retest; Correlation; Covariations; F-test | Influence of creativity + dance/movement skills | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking, Figural form B; Dance/Movement Skills Assessment |

| Szobiová and Zborteková, 2006 [54] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) | Difference between DHH and TH | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking |

| Yu et al., 2009 [55] | Quasi-experimental Research Design | Student’s t-test | Difference between DHH and TH | General Ability Tests (Smith and Whetton) |

| Daramola et al., 2019 [30] | Quasi-experimental Research Design, Control study | t-test | Difference between DHH and TH | New Creativity Test, Raven’s Test |

| Research Design | Methods Used | Aim | Tools | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marschark and West, 1985 [46] | Phenomenological Studies + Quasi-experimental Research Design | Coding + Descriptive analysis and correlation. | Relationships between language and cognition and creativity | Story Production |

| Marschark et al., 1986 [47] | Phenomenological studies and Quasi-experimental Research Design | Coding + Descriptive analysis and correlation. | Description of the development of linguistic and cognitive flexibility and its impact on creativity | Story Production |

| Silver, 1977 [53] | Observation + Quasi-experimental Research Design | Thematic analysis + Descriptive analysis and correlation. | Cognitive skills and creativity skills | Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking |

| Outputs | Verifiability of Research | |

|---|---|---|

| Gallagher, 1968 [34] | There were indications that regarding means in numerical achievement tests, there were interactions between age, sex, and creativity. | Verified test + Cronbach’s alpha reliability |

| Kaltsounis, 1971 [41] | Mean fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration scores by grade level within racial groups showed a noticeable tendency for scores of white deaf children to exceed those for black children in divergent thinking only in the earlier grades, while the scores of the blacks tended to exceed those of the whites at the fourth-grade level. | Verified test + Verifiability exists |

| Marschark and Clark, 1987 [44] | The use of inappropriate research tools leads to children with hearing impairments being underestimated. | No verifiability |

| Marschark et al., 1987 [45] | Deaf children have a much greater tendency towards language flexibility than is normally expected. | No verifiability |

| Outputs | Verifiability of Research | |

|---|---|---|

| Arnidha and Hidayatulloh, 2019 [29] | From the number of five respondents, it turned out that one of the respondents was more creative, one was not creative, and the remaining three showed average creativity. | No verifiability |

| Davies, 1984 [31] | Exercises in creative dramatics promote flexibility of function and attitude in hearing-impaired students. | No verifiability |

| Johnson, 1975 [36] | The results show that the respondents who had caught the onomatopoeic words had a significantly higher mean score than the respondents who had not caught the words. | Verified tests sample, method + Verifiability exists |

| Kaltsounis, 1969 [38] | The results obtained indicate that the quality and quantity of the creative originality scores of these two groups of deaf children are not a sufficient basis for concluding that either method of instruction is superior. | No verifiability |

| Laughton, 1988 [42] | A positive influence on the development of creative thinking was shown in all parameters in the application of the Creativity Curriculum in 12 activities. | Verified tests, sample, methods + Verifiability exists |

| Minarsih and Wahab, 2019 [48] | Creativity was described as improved in the target group. | No verifiability |

| Reber and Sherrill, 1981 [52] | Dance training led to significant improvements in originality, elaboration, total creative thinking score, and dance/movement skills. The rationale for including the creative arts, particularly dance, in curricula for hearing-impaired students was confirmed as being effective. | Verifiability exists |

| Outputs | Verifiability of Research | |

|---|---|---|

| Daramola et al., 2019 [30] | The creativity level of hearing-impaired students is essentially higher when contrasted with their hearing peers. The creativity level of females with hearing impairment is fundamentally higher than that of males. The finding further revealed that post-lingual hearing-impaired students have significantly higher creativity levels than their pre-lingual peers. | Reliability verified by split-half, Cronbach’s alpha |

| Ebrahim, 2006 [32] | The hearing children scored significantly (p < 0.05) higher than the deaf children in fluency, originality, and abstractness of titles. However, there were no significant differences between the deaf and hearing children in elaboration, resistance to premature closure, and creative strength (p < 0.05). | Clearly described validity and reliability |

| Ebrahim, 2006 [33] | The hearing children scored significantly (p < 0.05) higher than the deaf children in fluency, originality, and abstractness of titles. However, there were no significant differences between the deaf and hearing children in elaboration, resistance to premature closure, and creative strength (p < 0.05). | Verifiability exists |

| Halpin and Torrance, 1973 [28] | The deaf children studied by Kaltsounis (1970) scored markedly higher than the hearing children on verbal fluency and verbal originality. Blindness and deafness did not differentially affect the scores on the Torrance test for children in this study. | No verifiability |

| Hicks, 1942 [35] | Children with hearing impairments create different images (objects, nature), and intact children rather than animals, toys, or mixed objects. A problem was found especially with the description and creation of the story in children with hearing impairments. The children with hearing impairments worked with greater passion, were not critical of creative expression, and did not seek help and support. The hearing girls were significantly better than the deaf girls. | No verifiability |

| Johnson, 1975 [36] | The deaf children scored significantly higher than the hearing children on the Fluency, Flexibility, and Elaboration subtests of TTCT. The deaf children scored higher as their ages increased. | Verifiability exists |

| Johnson, 1977 [37] | The hearing respondents scored much higher than the deaf respondents. | Verifiability exists |

| Kaltsounis, 1970 [39] | The deaf children had better results than the hearing children in creative thinking abilities, except in grades 2 and 3 for fluency and grade 2 for originality and elaboration. The deaf and hearing males performed more poorly than the deaf and hearing females in figural fluency, flexibility, and elaboration. The opposite was the case in favor of the males for figural originality. | Verifiability exists |

| Kaltsounis, 1970 [40] | The older deaf children scored markedly higher than their hearing counterparts on fluency and originality but not on flexibility. In the case of verbal flexibility, the performance of the deaf children was equal to that of the hearing ones. | Verifiability exists |

| Lubin and Sherrill, 1980 [43] | The preschool deaf children were significantly inferior to the hearing children in motor creativity, as measured by the Torrance Test of Thinking Creatively in Action and Movement. | Verifiability exists |

| Marschark and West, 1985 [46] | The deaf children who used sign language used the same amount of figurative language as their hearing peers in English. | Verifiability exists |

| Marschark et al., 1986 [47] | The subjects here showed considerable use of creative language devices when evaluated in sign rather than vocal language. The present study, therefore, indicates that evaluating the linguistic and cognitive skills of deaf school children in terms of English underestimates their abstractive linguistic and cognitive abilities. | Reliability is described |

| Moorjhani et al., 1998 [49] | Comparison of intellect and creativity in both groups of respondents: in the RCPM test, the hearing children scored significantly higher, and creativity was not found to be a significant difference between the two groups in verbal items. The children with hearing impairments responded more to visual stimuli. | Verifiability exists |

| Pang and Horrocks, 1968 [50] | The deaf children scored lower than the hearing children on the Barron–Welsh Art Scale and Torrance Figural Tests of Creative Thinking. They were not interested in abstract figures but were more oriented toward concrete figures. In the Torrance dimensions, they scored about the same as the group of hearing children but were higher in processing. | Verifiability exists |

| Paszkowska-Rogacz, 1992 [51] | The level of creativity and other monitored items found in the tests was always lower in the deaf children than in the control sample of hearing children. | Verifiability exists |

| Silver, 1977 [53] | The deaf participants’ average scores (when compared to the hearing norms) were in the 88–99th percentile (i.e., originality, 99%; fluency, 97%; flexibility, 88%; and elaboration, 99%). The deaf participants’ pictures were judged to be more creative than those of the hearing participants. | Verifiability exists |

| Stanzione et al., 2013 [22] | The deaf students’ performance was equal to, or more creative than, that of the hearing students on the figural assessment of divergent thinking, but less creative on the verbal assessment. | Reliability is described |

| Szobiová and Zborteková, 2006 [54] | Differences were found only in some indicators of creative thinking: the adolescents with hearing impairment did not assign generalizing names to the drawings, they did not draw abstract themes and did not use symbols and signs in their drawings. | Verifiability exists |

| Yu et al., 2009 [55] | The deaf children were lower in verbal fluency, flexibility, originality, and figural flexibility. No difference was seen in figural fluency and originality. | Verifiability exists |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Potměšilová, P.; Potměšil, M.; Klugar, M. The Difference in the Creativity of People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Those with Typical Hearing: A Scoping Review. Children 2023, 10, 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081383

Potměšilová P, Potměšil M, Klugar M. The Difference in the Creativity of People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Those with Typical Hearing: A Scoping Review. Children. 2023; 10(8):1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081383

Chicago/Turabian StylePotměšilová, Petra, Miloň Potměšil, and Miloslav Klugar. 2023. "The Difference in the Creativity of People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Those with Typical Hearing: A Scoping Review" Children 10, no. 8: 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081383

APA StylePotměšilová, P., Potměšil, M., & Klugar, M. (2023). The Difference in the Creativity of People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing and Those with Typical Hearing: A Scoping Review. Children, 10(8), 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081383