Firearm Deaths among Youth in the United States, 2007–2016

Abstract

1. Introduction

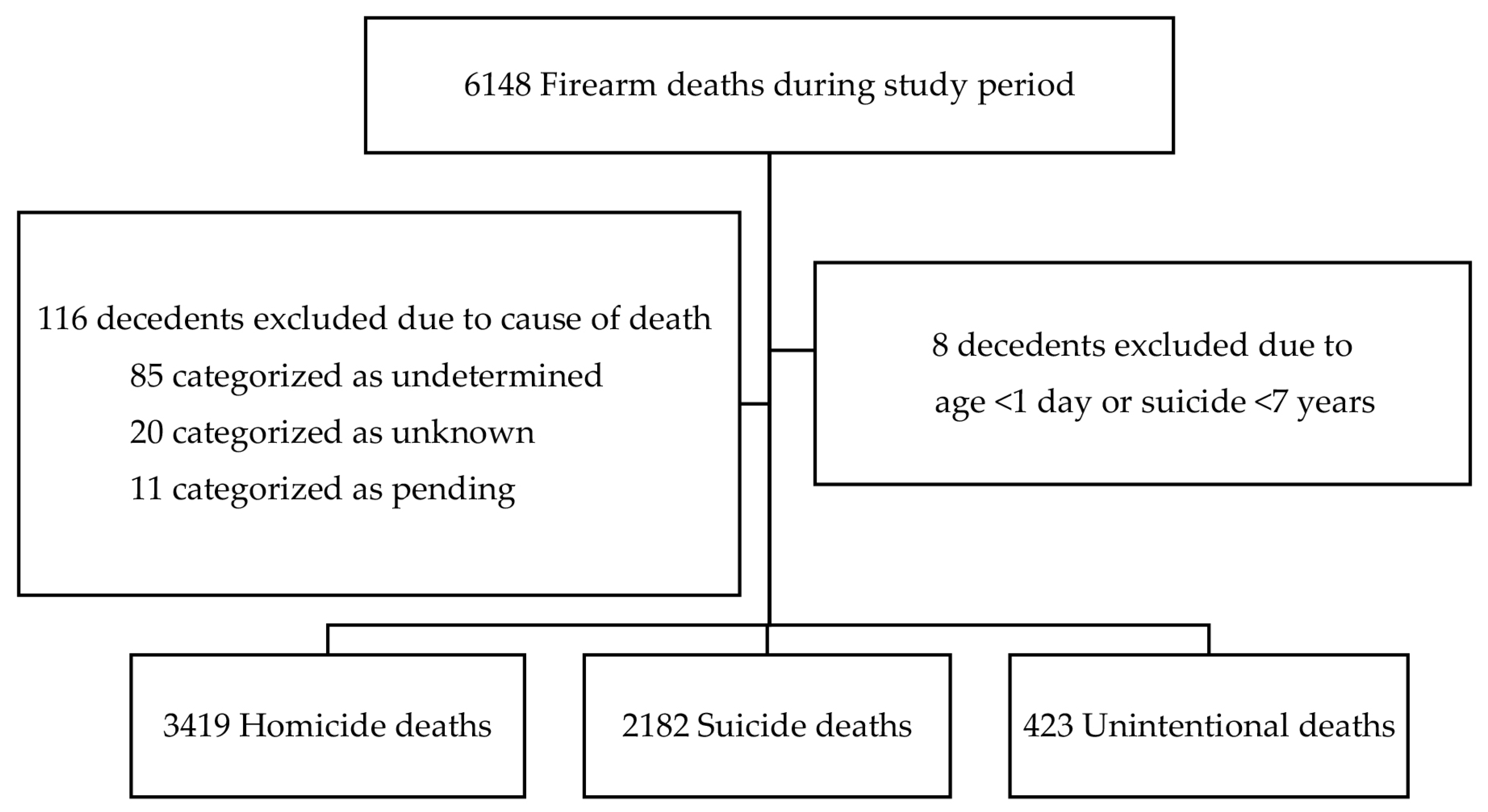

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Description of the Dataset

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goldstick, J.E.; Cunningham, R.M.; Carter, P.M. Current Causes of Death in Children and Adolescents in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1955–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, J.M.; Gaither, J.R.; Sege, R. Hospitalizations due to firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Available online: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars (accessed on 4 December 2022).

- Grinshteyn, E.; Hemenway, D. Violent death rates in the US compared to those of the other high-income countries, 2015. Prev. Med. 2019, 123, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, M.; Pahn, M.; Xuan, Z.; Ross, C.S.; Galea, S.; Kalesan, B.; Fleegler, E.; Goss, K.A. Firearm-related laws in all 50 US States, 1991–2016. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleegler, E.W.; Lee, L.K.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Hemenway, D.; Mannix, R. Firearm legislation and firearm-related fatalities in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.K.; Badolato, G.M.; Patel, S.J.; Iqbal, S.F.; Parikh, K.; McCarter, R. State gun laws and pediatric firearm-related mortality. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20183283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, H.A.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Rees, C.A.; Siegel, M.; Mannix, R.; Lee, L.K.; Sheehan, K.M.; Fleegler, E.W. Child access prevention firearm laws and firearm fatalities among children aged 0 to 14 Years, 1991–2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RAND Corporation. The Effects of Child-Access Prevention Laws. Available online: https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/child-access-prevention.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Zeoli, A.M.; Goldstick, J.; Mauri, A.; Wallin, M.; Goyal, M.; Cunningham, R.; FACTS Consortium. The association of firearm laws with firearm outcomes among children and adolescents: A scoping review. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 42, 741–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowd, M.D.; Sege, R.D.; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Executive Committee. Firearm-related injuries affecting the pediatric population. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1416–e1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Coyne-Beasley, T.; Runyan, C.W. Firearm ownership and storage practices, U.S. households, 1992–2002: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 27, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.A.; Franke, T.M.; Bastian, A.M.; Sor, S.; Halfon, N. Firearm storage patterns in US homes with children. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkenberry, J.; Schaechter, J. Reporting on pediatric unintentional firearm injury--who’s responsible. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 79, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowhani-Rahbar, A.; Simonetti, J.A.; Rivara, F.P. Effectiveness of interventions to promote safe firearm storage. Epidemiol. Rev. 2016, 38, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.J.; Rupp, L.; Pizarro, J.M.; Lee, D.B.; Branas, C.C.; Zimmerman, M.A. Risk and protective factors related to youth firearm violence: A scoping review and directions for future research. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 42, 706–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.M.; Carter, P.M.; Ranney, M.L.; Walton, M.; Zeoli, A.M.; Alpern, E.R.; Branas, C.; Beidas, R.S.; Ehrlich, P.F.; Goyal, M.K.; et al. Prevention of firearm injuries among children and adolescents consensus-driven research agenda from the firearm safety among children and teens (FACTS) consortium. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, E.G.; Hemenway, D. Homicide, suicide, and unintentional firearm fatality: Comparing the United States with other high-income countries, 2003. J. Trauma 2011, 70, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, W.E.; Barin, E.; McLaughlin, C.M.; Strumwasser, A.; Shekherdimian, S.; Arbogast, H.; Upperman, J.S.; Jensen, A.R. Pediatric firearm injuries in Los Angeles County: Younger children are more likely to be the victims of unintentional firearm injury. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monuteaux, M.C.; Mannix, R.; Fleegler, E.W.; Lee, L.K. Predictors and outcomes of pediatric firearm injuries treated in the emergency department: Differences by mechanism of intent. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Branas, C.C.; Myers, D.; Agrawal, N. Youth exposure to violence involving a gun: Evidence for adverse childhood experience classification. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 42, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.; Gombojav, N.; Solloway, M.; Wissow, L. Adverse childhood experiences, resilience and mindfulness-based approaches: Common denominator issues for children with emotional, mental, or behavioral problems. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blodgett, C.; Lanigan, J.D. The association between adverse childhood experience (ACE) and school success in elementary school children. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2018, 33, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, E.F.; Weiler, L.M.; Taussig, H.N. Adverse childhood experiences and health-risk behaviors in vulnerable early adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemenway, D. Importance of firearms research. Inj. Prev. 2019, 25, i1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranney, M.L.; Fletcher, J.; Alter, H.; Barsotti, C.; Bebarta, V.S.; Betz, M.E.; Carter, P.M.; Cerda, M.; Cunningham, R.M.; Crane, P.; et al. A consensus-driven agenda for emergency medicine firearm injury prevention research. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2017, 69, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Azrael, D.; Hemenway, D. Firearm availability and unintentional firearm deaths, suicide, and homicide among 5–14 year olds. J. Trauma 2002, 52, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwik, M.; Jay, S.; Ryan, T.C.; DeVylder, J.; Edwards, S.; Wilson, M.E.; Virden, J.; Goldstein, M.; Wilcox, H.C. Lowering the age limit in suicide risk screening: Clinical differences and screening form predictive ability. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 60, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Center for Fatality Review & Prevention. National Fatality Review Case Reporting System Data Dictionary-Version 5.1. Available online: https://ncfrp.org/wp-content/uploads/NCRPCD-Docs/DataDictionary_v5_1.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Covington, T.M. The US national child death review case reporting system. Inj. Prev. 2011, 17, i34–i37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The National Center for Fatality Review & Prevention. A Program Manual for Child Death Review. Available online: https://ncfrp.org/wp-content/uploads/NCRPCD-Docs/ProgramManual.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, A.; Coleman, A.; Shi, J.; Wheeler, K.; Xiang, H.; Kenney, B. In harm’s way: Unintentional firearm injuries in young children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 1020–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, D.C.; Reay, D.T.; Baker, S.A. Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: The source of the firearm. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1999, 153, 875–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, M.L.; Carr, B.G.; Kallan, M.J.; Branas, C.C.; Wiebe, D.J. Variation in pediatric and adolescent firearm mortality rates in rural and urban US counties. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.; Knox, L.; Fein, J.; Harrison, S.; Frisch, K.; Walton, M.; Dicker, R.; Calhoun, D.; Becker, M.; Hargarten, S.W. Before and after the Trauma Bay: The Prevention of Violent Injury Among Youth. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 53, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Eslinger, D.M.; Stolley, P.D. Hospital-based violence intervention programs work. J. Trauma–Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2006, 61, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborative on Gun Violence Research. Available online: https://www.ncgvr.org/grants.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Flaherty, M.R.; Klig, J.E. Firearm-related injuries in children and adolescents: An emergency and critical care perspective. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2020, 32, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roszko, P.J.; Ameli, J.; Carter, P.M.; Cunningham, R.M.; Ranney, M.L. Clinician attitudes, screening practices, and interventions to reduce firearm-related injury. Epidemiol. Rev. 2016, 38, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, M.S. Teaching firearms safety to children: Failure of a program. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2002, 23, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence and Prevention. Firearm Violence Prevention. Available online: www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/index.html (accessed on 23 February 2023).

| Total (n = 6024) | Homicide (n = 3419) | Suicide (n = 2182) | Unintentional (n = 423) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (±SD) | 14 (4) | 14 (5) | 16 (2) | 10 (6) |

| Median (IQR) | 16 (14–17) | 16 (14–17) | 16 (15–17) | 11 (4–15) |

| Total by Age Group | ||||

| 0–4 years | 412 (7%) | 284 (8%) | 0 | 128 (30%) |

| 5–9 years | 320 (5%) | 257 (8%) | Omitted 1 | 61 (15%) |

| 10–14 years | 1151 (19%) | 504 (15%) | 543 (25%) | 106 (25%) |

| 15–18 years | 4141 (69%) | 2374 (69%) | 1639 (75%) | 128 (30%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 4899 (81%) | 2710 (79%) | 1834 (84%) | 355 (84%) |

| Female | 1104 (18%) | 699 (20%) | 339 (16%) | 66 (16%) |

| Missing | 21 (<1%) | 10 (<1%) | 9 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 2216 (37%) | 1922 (56%) | 176 (8%) | 118 (28%) |

| Hispanic | 953 (16%) | 674 (20%) | 230 (11%) | 49 (12%) |

| Other | 252 (4%) | 123 (4%) | 97 (4%) | 21 (5%) |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 2504 (41%) | 638 (19%) | 1636 (75%) | 230 (54%) |

| Missing | 99 (2%) | 51 (1%) | 43 (2%) | 5 (1%) |

| Setting | ||||

| Urban | 4162 (69%) | 2729 (80%) | 1228 (56%) | 205 (48%) |

| Rural | 1225 (20%) | 340 (10%) | 717 (33%) | 168 (40%) |

| Missing | 637 (11%) | 350 (10%) | 237 (11%) | 50 (12%) |

| Psychosocial Characteristics | ||||

| Mental Health/Cognitive Disability History | ||||

| Yes | 1187 (20%) | 452 (13%) | 712 (33%) | 23 (5%) |

| No | 1907 (32%) | 1024 (30%) | 693 (32%) | 190 (45%) |

| Missing | 2930 (48%) | 1943 (57%) | 777 (35%) | 210 (50%) |

| Alcohol/Substance Abuse History | ||||

| Yes | 1175 (19%) | 711 (21%) | 436 (20%) | 28 (7%) |

| No | 2141 (36%) | 1099 (32%) | 800 (37%) | 242 (57%) |

| Missing | 2708 (45%) | 1609 (47%) | 946 (43%) | 153 (36%) |

| History of Criminal Behavior 2 | ||||

| Yes | 1291 (22%) | 977 (29%) | 284 (13%) | 30 (7%) |

| No | 2852 (47%) | 1412 (41%) | 1152 (53%) | 288 (68%) |

| Missing | 1881 (31%) | 1030 (30%) | 746 (34%) | 105 (25%) |

| Caregiver Receiving Social Assistance 3 | ||||

| Yes | 667 (11%) | 496 (15%) | 116 (5%) | 55 (13%) |

| No | 1048 (17%) | 411 (12%) | 552 (25%) | 85 (20%) |

| Missing | 4309 (72%) | 2512 (73%) | 1514 (70%) | 283 (67%) |

| History of Maltreatment 4 | ||||

| Yes | 1213 (20%) | 811 (24%) | 342 (16%) | 60 (14%) |

| No | 2402 (40%) | 1243 (36%) | 958 (44%) | 201 (48%) |

| Missing | 2409 (40%) | 1365 (40%) | 882 (40%) | 162 (38%) |

| Open Child Protective Services Case at Time of Death | ||||

| Yes | 265 (4%) | 188 (6%) | 62 (3%) | 15 (4%) |

| No | 4195 (70%) | 2306 (67%) | 1587 (73%) | 302 (71%) |

| Missing | 1564 (26%) | 925 (27%) | 533 (24%) | 106 (25%) |

| History of weapon offenses 5 | ||||

| Yes | 523 (9%) | 431 (12%) | 72 (3%) | 20 (5%) |

| No | 2356 (39%) | 846 (25%) | 1258 (58%) | 252 (59%) |

| Missing | 3145 (52%) | 2142 (63%) | 852 (39%) | 151 (36%) |

| Location of Incident | ||||

| Decedent’s Home | 2724 (45%) | 892 (26%) | 1609 (74%) | 223 (53%) |

| Relative’s Home | 319 (5%) | 159 (5%) | 109 (5%) | 51 (12%) |

| Friend’s Home | 533 (9%) | 385 (11%) | 81 (4%) | 67 (16%) |

| Other 6 | 2339 (39%) | 1903 (56%) | 363 (16%) | 73 (17%) |

| Missing | 109 (2%) | 80 (2%) | 20 (1%) | 9 (2%) |

| Relationship to Firearm Owner | ||||

| Self or Family Member | 2276 (38%) | 580 (17%) | 1440 (66%) | 256 (60%) |

| Other | 1210 (20%) | 1045 (31%) | 95 (4%) | 70 (17%) |

| Missing | 2538 (42%) | 1794 (52%) | 647 (30%) | 97 (23%) |

| Firearm Characteristics | ||||

| Firearm Type | ||||

| Handgun | 3829 (64%) | 2230 (65%) | 1317 (61%) | 282 (67%) |

| Shotgun | 634 (11%) | 204 (6%) | 371 (17%) | 59 (14%) |

| Hunting Rifle | 383 (6%) | 76 (2%) | 263 (12%) | 44 (10%) |

| Assault Rifle | 128 (2%) | 96 (3%) | 25 (1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Other 7 | 70 (1%) | 34 (1%) | 30 (1%) | 6 (1%) |

| Missing | 980 (16%) | 779 (23%) | 176 (8%) | 25 (6%) |

| Licensed Firearm | ||||

| Yes | 916 (15%) | 305 (9%) | 517 (24%) | 94 (22%) |

| No | 846 (14%) | 493 (14%) | 265 (12%) | 88 (21%) |

| Missing | 4262 (71%) | 2621 (77%) | 1400 (64%) | 241 (57%) |

| Safety features | ||||

| Yes | 369 (6%) | 128 (4%) | 189 (9%) | 52 (12%) |

| No | 1340 (22%) | 696 (20%) | 517 (24%) | 127 (30%) |

| Missing | 4315 (72%) | 2595 (76%) | 1476 (67%) | 244 (58%) |

| Locked storage | ||||

| Yes | 305 (5%) | 36 (1%) | 261 (12%) | 8 (2%) |

| No | 2126 (35%) | 877 (26%) | 951 (44%) | 298 (70%) |

| Missing | 3593 (60%) | 2506 (73%) | 970 (44%) | 117 (28%) |

| Store with Ammunition | ||||

| Yes | 1253 (21%) | 397 (12%) | 661 (30%) | 195 (46%) |

| No | 248 (4%) | 52 (1%) | 165 (8%) | 31 (7%) |

| Missing | 4523 (75%) | 2970 (87%) | 1356 (62%) | 197 (47%) |

| Stored Loaded | ||||

| Yes | 999 (17%) | 407 (12%) | 362 (17%) | 230 (54%) |

| No | 379 (6%) | 55 (2%) | 295 (13%) | 29 (7%) |

| Missing | 4646 (77%) | 2957 (86%) | 1525 (70%) | 164 (39%) |

| Decedent Characteristic | Homicide vs. Unintentional | Suicide vs. Unintentional |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||

| 15–18 years | Reference | Reference |

| 0–4 years | 0.1 (0.1–0.2) | Omitted 1 |

| 5–9 years | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | Omitted 1 |

| 10–14 years | 0.3 (0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | -------- | -------- |

| Female | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | Reference | Reference |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 5.9 (4.6–7.5) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) |

| Hispanic | 5.0 (3.6–6.9) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) |

| Other | 2.3 (1.4–3.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

| Setting | ||

| Rural | Reference | Reference |

| Urban | 6.6 (5.2–8.3) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) |

| Missing | 3.5 (2.4–4.9) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| Multiple Imputation | Non-Imputed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decedent | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR 1 | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR 1 |

| Characteristic | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

| Documented Maltreatment | ||||

| No | ------- | ------- | ------- | ------- |

| Yes | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 2.2 (1.6–3.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) |

| Open Child Protective Services Case at the Time of Death | ||||

| No | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Yes | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 1.6 (0.9–2.8) | 1.6 (0.9–3.0) |

| Incident Location | ||||

| Child’s Home | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Friend’s Home | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) |

| Relative’s Home | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| Other | 6.5 (5.0–8.6) | 3.2 (2.4–4.4) | 6.0 (4.6–7.9) | 3.1 (2.3–4.2) |

| Firearm Type | ||||

| Other | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Handgun | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) |

| Hunting Rifle | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.4 (0.2–0.9) |

| Shotgun | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.8 (0.4–1.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) |

| Relationship to Firearm Owner | ||||

| Other | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Self or Family | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) |

| Multiple Imputation | Non-Imputed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decedent | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR 1 | Unadjusted OR | Adjusted OR 1 |

| Characteristic | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) |

| Documented Maltreatment | ||||

| No | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Yes | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

| Open Child Protective Services Case at the Time of Death | ||||

| No | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Yes | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 1.3 (0.6–3.1) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 1.7 (0.7–4.2) |

| Incident Location | ||||

| Child’s Home | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Friend’s Home | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.1) |

| Relative’s Home | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.2 (0.2–0.6) |

| Other | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.4 (0.2–0.5) |

| Firearm Type | ||||

| Other | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Handgun | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | 2.2 (1.0–4.6) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.3) |

| Hunting Rifle | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) | 2.2 (0.9–5.1) | 1.4 (0.7–2.8) | 2.1 (0.9–4.8) |

| Shotgun | 1.6 (0.9–3.1) | 2.1 (0.9–4.6) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | 2.0 (0.9–4.4) |

| Relationship to Firearm Owner | ||||

| Other | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Self or Family | 3.9 (2.8–5.6) | 6.8 (4.2–10.8) | 4.1 (3.0–5.8) | 8.2 (5.2–12.8) |

| Firearm Safety Features | ||||

| Yes | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| No | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) |

| Firearm Locked | ||||

| No | -------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Yes | 6.7 (3.2–13.6) | 4.2 (2.1–8.9) | 10.2 (0.5–20.1) | 5.6 (2.5–12.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trigylidas, T.E.; Schnitzer, P.G.; Dykstra, H.K.; Badolato, G.M.; McCarter, R., Jr.; Goyal, M.K.; Lichenstein, R. Firearm Deaths among Youth in the United States, 2007–2016. Children 2023, 10, 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081359

Trigylidas TE, Schnitzer PG, Dykstra HK, Badolato GM, McCarter R Jr., Goyal MK, Lichenstein R. Firearm Deaths among Youth in the United States, 2007–2016. Children. 2023; 10(8):1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081359

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrigylidas, Theodore E., Patricia G. Schnitzer, Heather K. Dykstra, Gia M. Badolato, Robert McCarter, Jr., Monika K. Goyal, and Richard Lichenstein. 2023. "Firearm Deaths among Youth in the United States, 2007–2016" Children 10, no. 8: 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081359

APA StyleTrigylidas, T. E., Schnitzer, P. G., Dykstra, H. K., Badolato, G. M., McCarter, R., Jr., Goyal, M. K., & Lichenstein, R. (2023). Firearm Deaths among Youth in the United States, 2007–2016. Children, 10(8), 1359. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081359