Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety and Their Co-Occurrence among Orphaned Children in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background to the Study

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection Tool

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

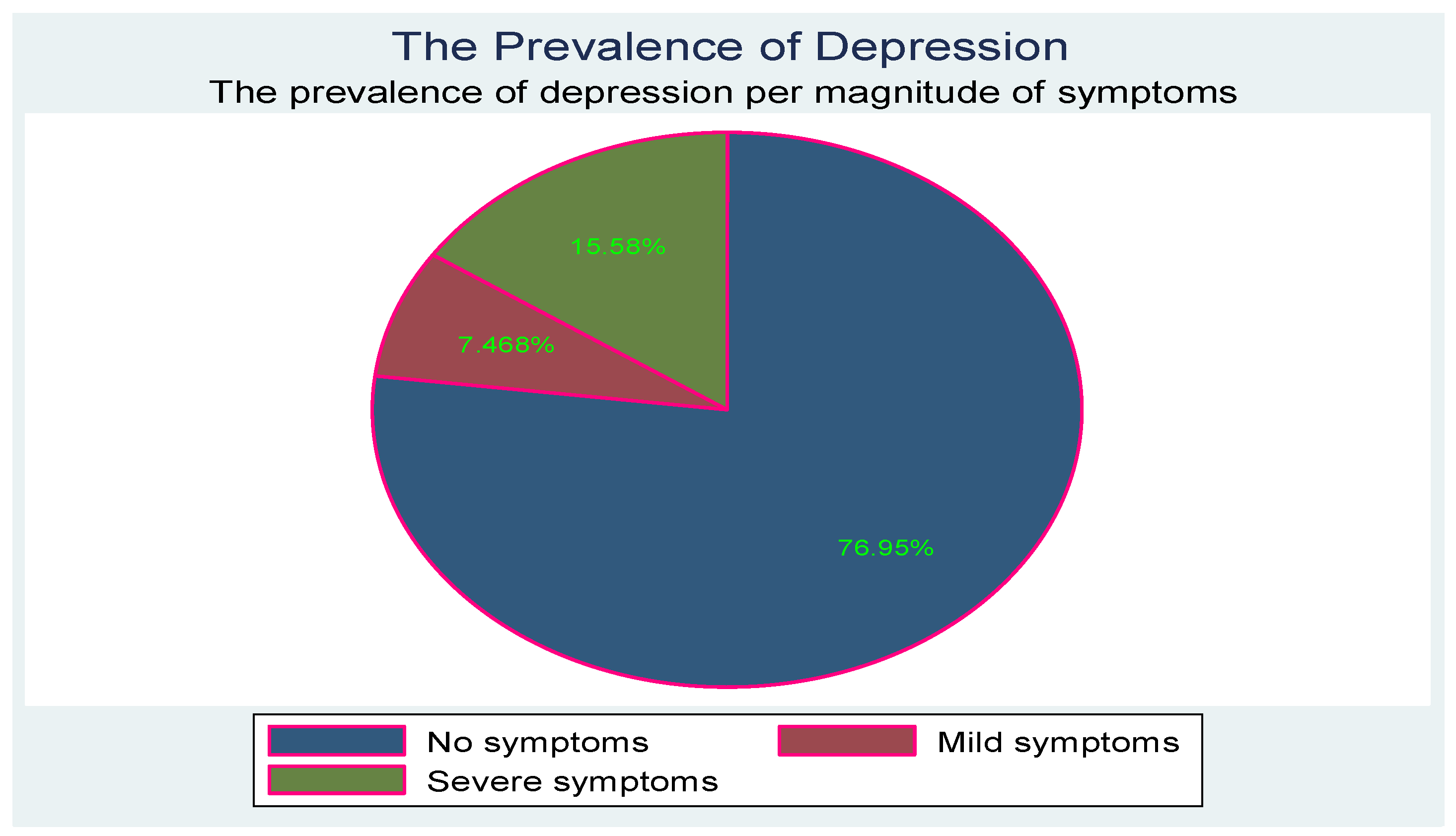

3.2. The Prevalence of Depression Symptoms

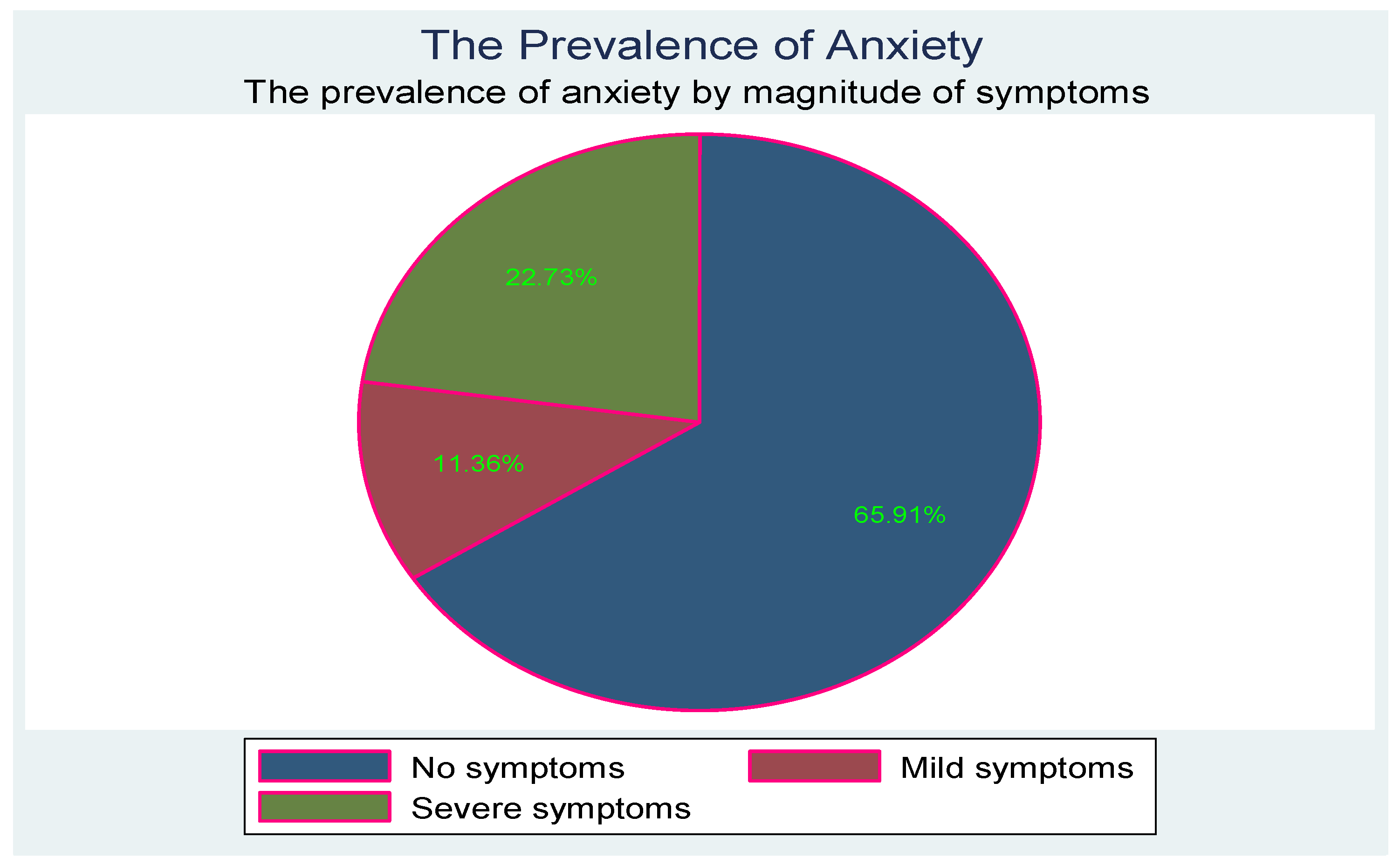

3.3. Prevalence of Anxiety Symptoms

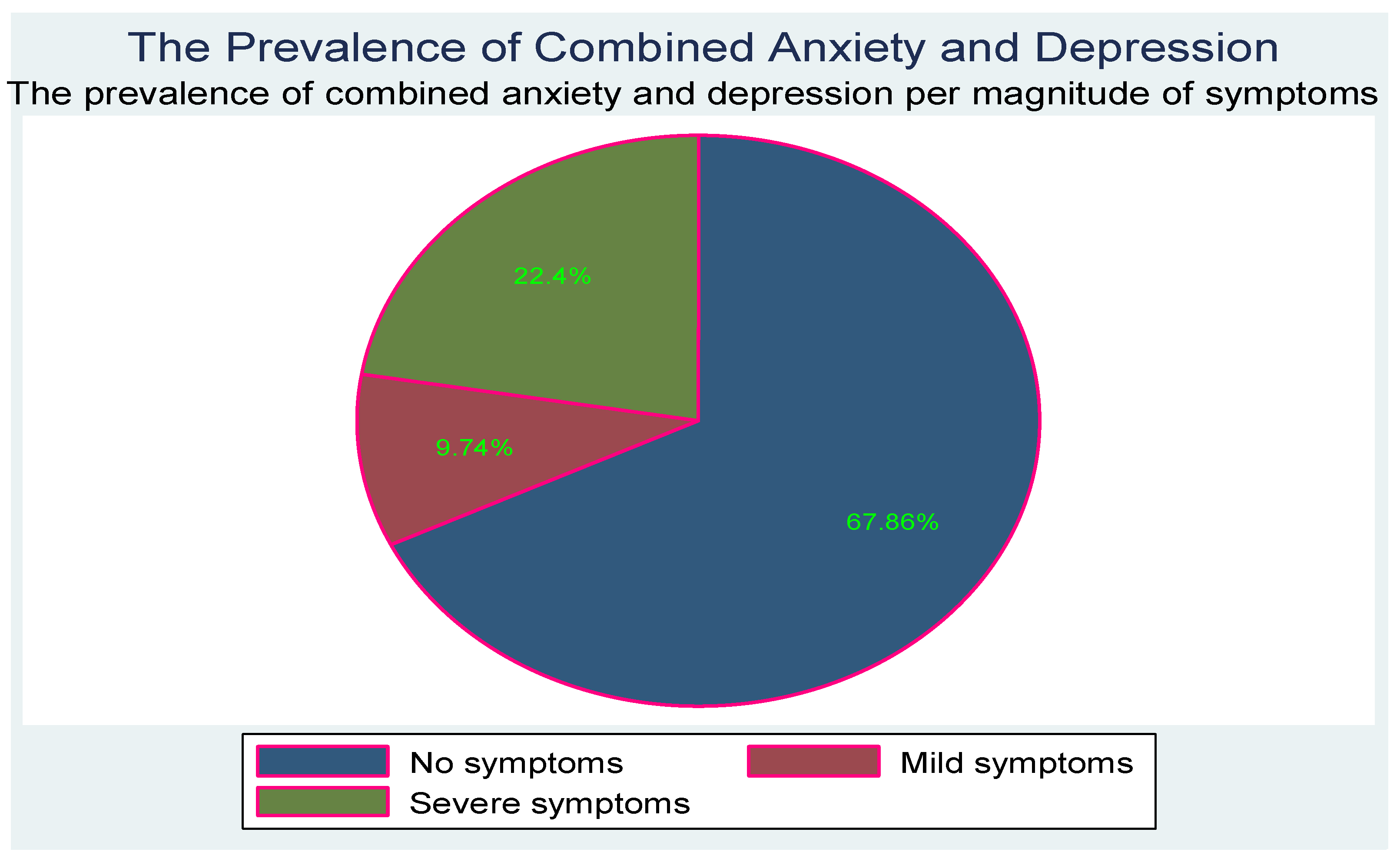

3.4. Co-Occurrence of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Research Implications

4.2. Practical Clinical Implications

4.3. Limitations of the Study

4.4. Strengths of the Study

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

- The Department of Social Development, which is the government entity responsible for the well-being of vulnerable children, should formally integrate routine mental health assessment and service provision for all orphaned children.

- Further study attention be given to causes of orphan-hood and responsive interventions, as there are reports that the severity of mental challenges may be influenced by the cause of the parents’ deaths [40,41,42]. This may therefore enable the development of custom-made mental health interventions for orphans.

- In the context of the many orphans of school-going ages, schools be provided with resources to develop programs to screen for mental health challenges among children, to enable referral to appropriate services.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fuggle, P.; Dunsmuir, S.; Curry, V. CBT with Children, Young People and Families; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. How Does the Death of a Parent Affect a Child. Parenting for Brain. 4 October 2022. Available online: https://www.parentingforbrain.com./death-of-aparent (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- UNICEF South Africa. Child Protection: Orphans and Vulnerable Children. 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/global-annual-results-2019-goal-area-3 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Meintjes, H.; Hall, K.; Sambu, W. Demography of South Africa’s Children. 2015. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/69143271/Demography_of_South_Africas_children20210907-29272-qr8uq0.pdf?1631003976=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DDemography_of_South_Africas_children.pdf&Expires=1690281231&Signature=Q91qQM44RqC9aDFqM8WtMXt9zX1RPpunEgKdhckJk0Unq67Wo07FxOoUi84AezSN0OcGpz7VC-xH-31aIEk1C-nlFvDDhUYDZyXy2w6jPKhvfptrI2PtmrYnKZyh1a4WK-oL3eMG25XNSpnytFXbfPMZ1hyfXaiZ6Jx5SQygkRzl0h9mM95agUY3usXow4f8a2hk6v6emFsRW-tHjwcP~WvtL0wDjSLZInvoZ6IRCfCenp0f~eVh-VazsL0UNwiUhXVm02nmQdtVXChyUOEVT--9nkmk3TeeCQKy0EBCLtGLhMANSyyCX~de42LSfdQvtZkhvltFO1TQzbqAQ10KyA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Sherr, L.; Croome, N.; Clucas, C.; Brown, E. Differential effects of single and double parental death on child emotional functioning and daily life in South Africa. Child Welf. 2014, 93, 149–172. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF South Africa. COVID-19: The Children Orphaned in South Africa. 2022. Available online: https://gdc.unicef.org/resource/covid-19-children-orphaned-south-africa (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Ibrahim, A.; El-Bilsha, M.A.; El-Gilany, A.H.; Khater, M. Prevalence and predictors of depression among orphans in Dakahlia’s orphanages, Egypt. Int. J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2012, 4, 2036. [Google Scholar]

- Shiferaw, G.; Bacha, L.; Tsegaye, D. Prevalence of depression and its associated factors among orphan children in orphanages in Ilu Abba Bor Zone, South West Ethiopia. Psychiatry J. 2018, 2018, 6865085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avakyan, T.V.; Volikova, S.V. Social anxiety in children. Psychol. Russ. 2014, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Singh, A.; Suvidha, D. Well-being of Orphans: A Review on their Mental Health Status. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Technol. 2016, 2, 180–184. [Google Scholar]

- Thabet, A.A.; Elhelou, M.; Vostanis, P. Prevalence of PTSD, depression, and anxiety among orphaned children in the Gaza Strip. EC Paediatr. 2017, 5, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cherng Ong, K.I.; Yi, S.; Tuot, S.; Chhoun, P.; Shibanuma, A.; Yasuoka, J.; Jimba, M. What are the factors associated with depressive symptoms among orphans and vulnerable children in Cambodia? Institutionalised Child. Explor. Beyond 2017, 4, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, K.; Reardon, C.; Quinlan, T.; George, G. Children’s psychosocial wellbeing in the context of HIV/AIDS and poverty: A comparative investigation of orphaned and non-orphaned children living in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pappin, M.; Marais, L.; Sharp, C.; Lenka, M.; Cloete, J.; Skinner, D.; Serekoane, M. Socio-economic status and socio-emotional health of orphans in South Africa. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, L.; Sharp, C.; Serekoane, M.; Skinner, D.; Cloete, J.; Rani, K.; Pappin, M.; Lenka, M. What role for community? In The Routledge Handbook of Community Development Research; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018; Volume 19, p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras, J.A.; Martín-Vivar, M.; Sandin, B.; San Luis, C.; Pineda, D. The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale: A systematic review and reliability generalization meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 218, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaufus, L.; Verlinden, E.; Van Der Wal, M.; Kösters, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Chinapaw, M. Psychometric evaluation of two short versions of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visagie, L.; Loxton, H.; Silverman, W.K. Research Protocol: Development, implementation and evaluation of a cognitive behavioural therapy-based intervention programme for the management of anxiety symptoms in South African children with visual impairments. Afr. J. Disabil. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebesutani, C.; Reise, S.P.; Chorpita, B.F.; Ale, C.; Regan, J.; Young, J.; Higa-McMillan, C.; Weisz, J.R. The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale-Short Version: Scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Sambu, W. Demography of South Africa’s children. S. Afr. Child Gauge 2019, 216–220. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Trisha-Ramraj/publication/337973440_Prioritising_child_and_adolescent_health_A_human_rights_imperative/links/5df8a47392851c83648324d5/Prioritising-child-and-adolescent-health-A-human-rights-imperative.pdf#page=216 (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Casale, M.; Wild, L.; Cluver, L.; Kuo, C. Social support as a protective factor for depression among women caring for children in HIV-endemic South Africa. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch, M.; Posel, D. Who cares for children? A quantitative study of childcare in South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 2018, 35, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emovon, S.O.; Gutura, P.; Ntombela, N.H. Caring for non-relative foster children in South Africa: Voices of female foster parents. Ubuntu J. Confl. Soc. Transform. 2019, 8, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, N.; van Rensburg, A.J. Clinical and psycho-social profile of child and adolescent mental health care users and services at an urban child mental health clinic in South Africa. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2013, 16, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yilmaz, F.; Gungor Ozcan, D.; Gokoglu, A.G.; Turkyilmaz, D. The effect of poverty on depression among Turkish children. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2021, 38, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, K.B.; Apidechkul, T.; Srichan, P.; Bhatt, N. Depressive symptoms among orphans and vulnerable adolescents in childcare homes in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoza, T.V.; Mokgatle, M.M. Prevalence of Depression Symptoms amongst Orphaned Adolescents at Secondary Schools in Townships of South Africa. Open Public Health J. 2021, 14, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itayi, M.; Wonder, M. The Interface of Orphan-hood and Schooling Experiences in Rural High Schools in the Republic of Zimbabwe. J. Pan Afr. Stud. 2018, 11, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Biltagi, M.; Sarhan, E.A. Anxiety disorder in children: Review. J. Paediatr. Care Insight 2016, 1, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluver, L.D.; Orkin, M.; Gardner, F.; Boyes, M.E. Persisting mental health problems among AIDS-orphaned children in South Africa. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.; Fazeli, M. Depression in children. Aust. Fam. Physician 2017, 46, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wichers, R.H.; van der Wouw, L.C.; Brouwer, M.E.; Lok, A.; Bockting, C.L. Psychotherapy for co-occurring symptoms of depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2022, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitsko, R.H.; Holbrook, J.R.; Ghandour, R.M.; Blumberg, S.J.; Visser, S.N.; Perou, R.; Walkup, J.T. Epidemiology and impact of health care provider–diagnosed anxiety and depression among US children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2018, 39, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, N.; Fouad, A. Psychosocial and developmental status of orphanage children: Epidemiological study. Curr. Psychiatry 2010, 17, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Popovic, D.; Schmitt, A.; Kaurani, L.; Senner, F.; Papiol, S.; Malchow, B.; Fischer, A.; Schulze, T.G.; Koutsouleris, N.; Falkai, P. Childhood trauma in schizophrenia: Current findings and research perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M.T.; Cannon, M.; Chambers, D.; Conroy, R.M.; Coughlan, H.; Dodd, P.; Healy, C.; O’Donnell, L.; Clarke, M.C. Childhood trauma and adult mental disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2021, 143, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Colich, N.L.; Rodman, A.M.; Weissman, D.G. Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.R.; Mucheuki, C.; Govender, K.; Quinlan, T. Psychosocial and health risk outcomes among orphans and non-orphans in mixed households in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2015, 14, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flisher, A.J.; Dawes, A.; Kafaar, Z.; Lund, C.; Sorsdahl, K.; Myers, B.; Thom, R.; Seedat, S. Child and adolescent mental health in South Africa. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2012, 24, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokitimi, S.; Schneider, M.; de Vries, P.J. Child and adolescent mental health policy in South Africa: History, current policy development and implementation, and policy analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G.; Dandona, R.; Kumar, G.A.; Ramgopal, S.P.; Dandona, L. Depression among AIDS-orphaned children higher than among other orphaned children in southern India. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2014, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nyoni, T.; Nabunya, P.; Ssewamala, F.M. Perceived social support and psychological wellbeing of children orphaned by HIV/AIDS in Southwestern Uganda. Vulnerable Child. Youth Stud. 2019, 14, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Participants | 308 | 100 | |

| Village | Maandagshoek | 187 | 60.71 |

| Ribacross | 121 | 39.29 | |

| Gender of participants | Females | 167 | 54.22 |

| Males | 141 | 45.78 | |

| Age of participants | 8–10 years | 132 | 42.86 |

| 11–12 years | 176 | 57.14 | |

| Grade | Up to 5 | 172 | 55.84 |

| 6 and 7 | 136 | 44.16 | |

| Deceased parent/s | Both parents | 52 | 16.88 |

| Father only | 129 | 41.88 | |

| Mother only | 127 | 41.23 | |

| Caregiver | Aunt | 31 | 10.06 |

| Brother | 2 | 0.65 | |

| Father | 25 | 8.12 | |

| Grandfather | 1 | 0.32 | |

| Grandmother | 109 | 35.39 | |

| Mother | 115 | 37.34 | |

| Sister | 18 | 5.84 | |

| Uncle | 7 | 2.27 | |

| Age category of caregiver | Adult | 173 | 56.17 |

| Older person | 91 | 29.55 | |

| Youth | 44 | 14.29 | |

| Gender of caregiver | Female | 273 | 88.64 |

| Male | 35 | 11.36 | |

| Employment status of caregiver | Employed | 74 | 24.03 |

| Unemployed | 234 | 75.97 | |

| Head of household | Grandparent | 145 | 47.08 |

| Parent | 123 | 39.94 | |

| Sibling | 12 | 3.90 | |

| Other relatives | 28 | 9.09 | |

| Number of people in household | 0 to 5 | 107 | 34.74 |

| 6 and above | 201 | 65.26 | |

| Number of siblings | 0 to 3 | 199 | 64.61 |

| 4 and above | 109 | 35.39 | |

| Number of children in household | 0 to 4 | 229 | 74.35 |

| 5 and above | 79 | 25.65 | |

| Number of people employed in household | None | 227 | 73.70 |

| 1 to 2 | 59 | 19.16 | |

| 3 and above | 22 | 7.14 | |

| Variable | p-Value |

|---|---|

| Anxiety symptoms | |

| Age | 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.004 |

| Number of children in household | 0.002 |

| Placed in foster care | 0.000 |

| Head of household | 0.002 |

| Depression symptoms | |

| Grade | 0.005 |

| Number of children in household | 0.004 |

| Placed in foster care | 0.004 |

| Enough food | 0.033 |

| Co-occurrence of anxiety and depression symptoms | |

| Grade | 0.046 |

| Placed in foster care | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mokwena, K.E.; Magabe, S.; Ntuli, B. Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety and Their Co-Occurrence among Orphaned Children in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province. Children 2023, 10, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081279

Mokwena KE, Magabe S, Ntuli B. Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety and Their Co-Occurrence among Orphaned Children in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province. Children. 2023; 10(8):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081279

Chicago/Turabian StyleMokwena, Kebogile Elizabeth, Success Magabe, and Busisiwe Ntuli. 2023. "Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety and Their Co-Occurrence among Orphaned Children in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province" Children 10, no. 8: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081279

APA StyleMokwena, K. E., Magabe, S., & Ntuli, B. (2023). Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety and Their Co-Occurrence among Orphaned Children in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province. Children, 10(8), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081279