Children with Disabilities in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of COVID-19 Policies through a Disability Rights Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.1.1. Data Collection

2.1.2. Data Extraction

2.2. Analysis

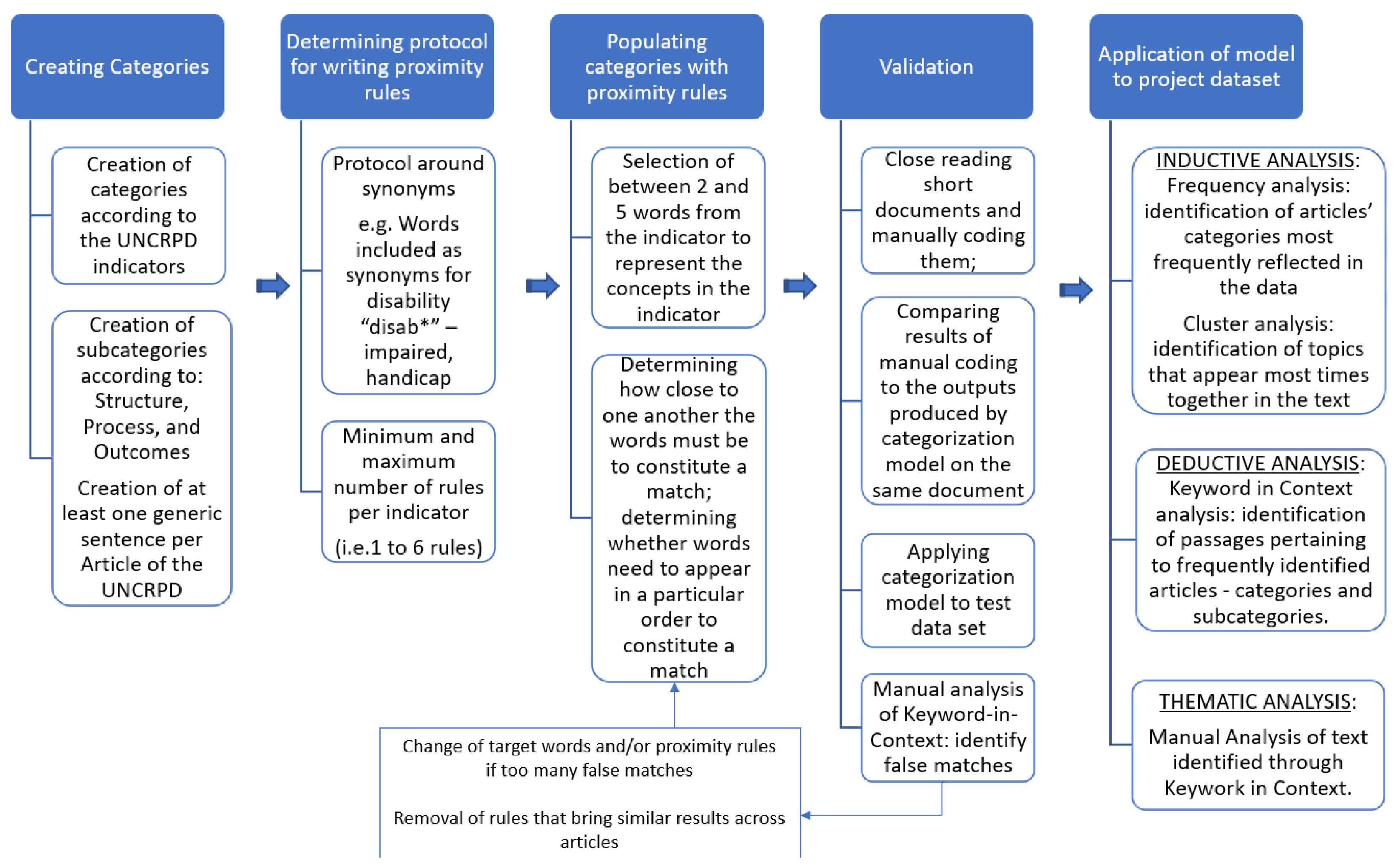

2.2.1. Categorization Models

2.2.2. Descriptive and Content Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Policy Documents

3.2. Mental Health Analytical Model

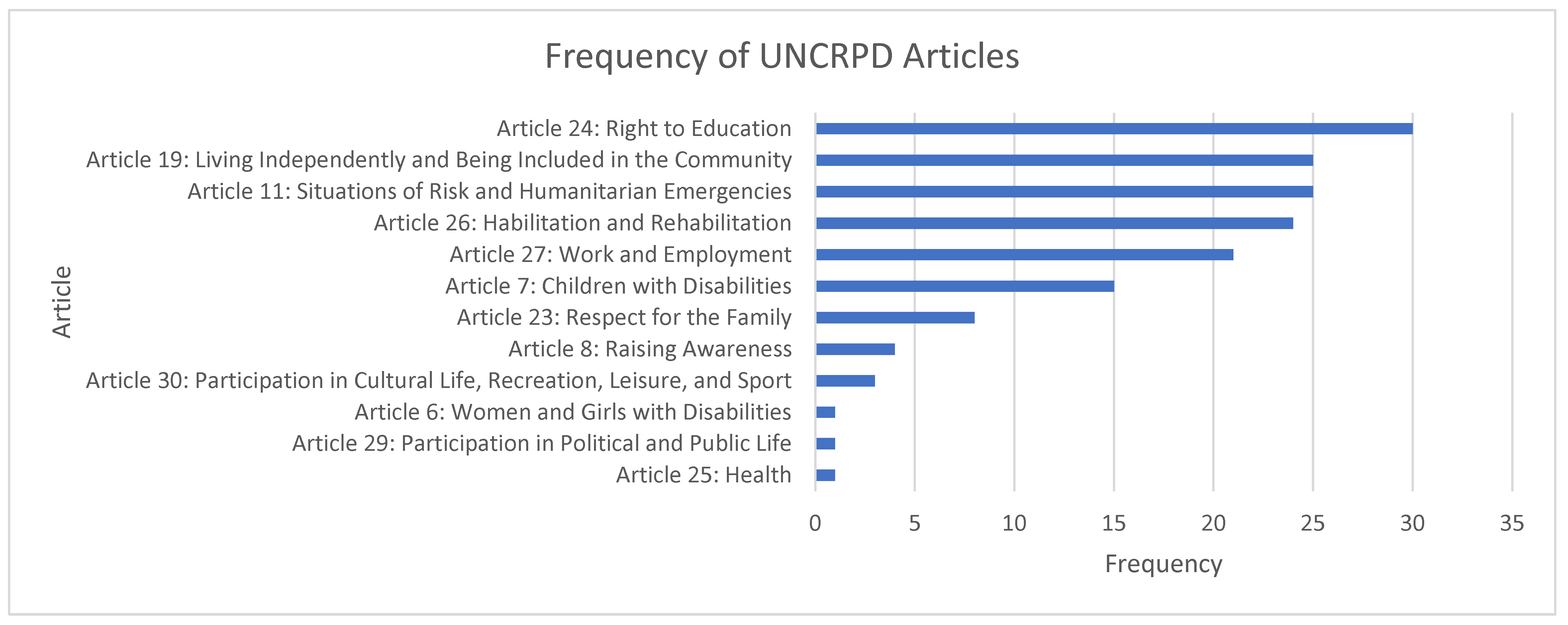

3.3. UN CRPD Analytical Model

3.3.1. Article 24: Education

3.3.2. Article 11: Situations of Risk and Emergency

3.3.3. Article 19: Living Independently

3.3.4. Article 26: Habilitation and Rehabilitation

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- Screening form for documents to be retained for analysis:

- Policy Name

- Link

- Q1. Does this policy pertain to persons with disabilities?

- Q2. Is this policy inclusive of persons with disabilities?

- Decision (Include/Exclude)

- Reason for exclusion

- Comments

Appendix C

- Visualization of Mental Health Analytical Model

- Mental health

- ◦

- Stressors

- ◦

- Barriers

- ▪

- Environmental barriers

- ▪

- Structural barriers

- ▪

- Attitudinal barriers

- ▪

- Medical barriers

- ◦

- Symptoms and outcomes

Appendix D

- Visualization of UN CRPD Analytical Model (Examples using selected articles)

- UN CRPD

- ◦

- Article 6: Women and Girls

- ▪

- Structure

- Nondiscrimination and equality

- Full development, advancement, and empowerment of women

- ▪

- Process

- Nondiscrimination and equality

- Full development, advancement, and empowerment of women

- ▪

- Outcomes

- Nondiscrimination and equality

- Full development, advancement, and empowerment of women

- ◦

- Article 7: Children with Disabilities

- ▪

- Structure

- Equality and identity

- Best interest for the child and respect for evolving capacities

- Respect for the views of the child

- ▪

- Process

- Equality and nondiscrimination

- Survival, development, and preservation of identity

- Best interests of and respect for the views of the child

- ▪

- Outcomes

- Equality, identity, and best interest of the child

- Respect for the views of the child

- Article 11: Situations of Risk and Humanitarian Emergencies

- ▪

- Structure

- Prevention and response

- Recovery, reconstruction, and reconciliation

- ▪

- Process

- Prevention and preparedness

- Rescue and response

- Recovery, reconstruction, and reconciliation

- ▪

- Outcomes

- Prevention and preparedness

- Rescue and response

- Recovery, reconstruction, and reconciliation

- ◦

- Article 23: Respect for Family

- ▪

- Structure

- Nondiscrimination in family life

- Parental rights of persons with disabilities

- Right of children with disabilities to grow up in a family environment within the community

- ▪

- Process

- Family life and parental rights

- Right of children with disabilities to grow up in a family environment within the community

- ▪

- Outcomes

- Nondiscrimination in family life

- Parental rights of persons with disabilities

- Right of children with disabilities to grow up in a family environment within the community

- ◦

- Article 24: Education

- ▪

- Structure

- Inclusive education

- Quality and free primary and secondary education

- Access to tertiary education, vocational training, and lifelong learning

- Inclusive teaching

- ▪

- Process

- Inclusive education

- Quality and free primary and secondary education

- Access to tertiary education, vocational training, and lifelong learning

- Inclusive teaching

- ▪

- Outcomes

- Inclusive education

- Quality and free primary and secondary education

- Access to tertiary education, vocational training, and lifelong learning

- Inclusive teaching

References

- Turk, M.A.; McDermott, S. The COVID-19 pandemic and people with disability. Disabil. Health J. 2020, 13, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare, T.; Ndagire, F.; Seketi, Q.E. Triple jeopardy: Disabled people and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 397, 1331–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, M.A.; Mitra, M. COVID-19 and people with disability: Social and economic impacts. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevay Grooms, A.O.; Rubalcaba, J.A.-A. The COVID-19 Public Health and Economic Crises Leave Vulnerable Populations Exposed; Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, G.C.; Laryea-Adjei, G.; Vike-Freiberga, V.; Abubakar, I.; Dakkak, H.; Devakumar, D.; Johnsson, A.; Karabey, S.; Labonté, R.; Legido-Quigley, H.; et al. Safeguarding people living in vulnerable conditions in the COVID-19 era through universal health coverage and social protection. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e86–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenov, T.; Brennan, C.S. The global COVID-19 disability rights monitor: Implementation, findings, disability studies response. Disabil. Soc. 2021, 36, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillmore, M. Some Young Adults with Disabilities are Stuck in Long-Term Care. They Say That’s Discrimination. Broadview. Available online: https://broadview.org/young-people-with-disabilities-long-term-care/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Rodriguez-Pereira, J.; de Armas, J.; Garbujo, L.; Ramalhinho, H. Health care needs and services for elder and disabled population: Findings from a barcelona study. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S.; Gosden-Kaye, E.Z.; Jarman, H.; Winkler, D.; Douglas, J.M. A scoping review to explore the experiences and outcomes of younger people with disabilities in residential aged care facilities. Brain Inj. 2020, 34, 1446–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, J. Left out: Children and Youth with Special Needs in the Pandemic. Available online: https://rcybc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CYSN_Report.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Schuengel, C.; Tummers, J.; Embregts, P.J.C.M.; Leusink, G. Impact of the initial response to COVID-19 on long-term care for people with intellectual disability: An interrupted time series analysis of incident reports. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, E.; Kara, A.; Bonnielin, K.S. COVID-19 vaccine prioritisation for people with disabilities. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e361. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF; World Health Organization; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Interim Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention and Control in Schools; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN Sustainable Development Group. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Children; UN Sustainable Development Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Combatting COVID-19′s Effect on Children; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Children with Disabilities in Emergencies. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/disabilities/emergencies (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. COVID-19 and the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Guidance; Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. COVID-19 Response: Considerations for Children and Adults with Disabilities; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Disability Alliance. Toward a Disability-Inclusive COVID19 Response: 10 Recommendations from the International Disability Alliance; International Disability Alliance: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Disability Considerations during the COVID-19 Outbreak; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mabita, N. Updated Statement: Ethical Medical Guidelines in COVID-19–Disability Inclusive Response; European Disability Forum: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19: Early Evidence of the Pandemic’s Impact: Scientific Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Mental Health Action; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. Children with Disabilities: Ensuring their Inclusion in COVID-19 Response Strategies and Evidence Generation; United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, P.; Clinton, J.; Kerber, R.; Khabaza, T.; Reinartz, T.P.; Shearer, C.; Wirth, R. CRISP-DM 1.0: Step-by-Step Data Mining Guide. 2000. Available online: http://www.citeulike.org/group/1598/article/1025172 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- World Health Organization Mental Health & COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/mental-health-and-covid-19 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights SDG-CRPD Resource Package. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/disabilities/sdg-crpd-resource-package (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Cogburn, D.; Shikako-Thomas, K.; Lai, J. Using Computational Text Mining to Understand Public Priorities for Disability Policy Towards Children in Canadian National Consultations. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shikako, K.; Lencucha, R.; Hunt, M.; Jodoin, S.; Elsabbagh, M.; Hudon, A.; Cogburn, D.; Chandra, A.; Gignac-Eddy, A. How did Governments Address the Needs of People with Disabilities during the COVID-19 Pandemic? An Analysis of 14 Countries’ policies Based on the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Guidance: Congregate Living for Vulnerable Populations; Ontario Ministry of Health: Ontario, ON, Toronto, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Conseil Scolaire Francophone Provincial de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador. Re-Entry Plan 2020–2021; Conseil Scolaire Francophone Provincial de Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador: St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yukon Education. Yukon Learning Continuity Requirements for the 2020–21 School Year; Yukon Education: Whitehorse, YT, Cananda, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. GNWT’s Response to COVID-19: Advice for Parents; Northwest Territories Health and Social Services: Yellowknife, NT, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Accessibility for Manitobans Act. Maintaining Accessibility during COVID-19; Manitoba Accessibility Office: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group. Rapid Evidence Report; Alberta Health Services: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of British Columbia. COVID-19: People with Disabilities; Government of British Columbia: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of New Brunswick. Caregiver Fatigue; Government of New Brunswick: Fredericton, NB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-15&chapter=4&clang=_en (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Nova Scotia’s Back to School Plan; Department of Education and Early Childhood Development: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministere de la Sante et des services Sociaux. Directives Pour Prévenir le Déconditionnement des Personnes Ayant une Déficience ou un Trouble du Spectre de L’autisme Ainsi que Celles Ayant une Problématique de Santé Physique Nécessitant des Services de Réadaptation Fonctionnelle Intensive, Modérée ou Post-Aiguë en Contexte de Pandémie; Ministere de la Sante et des Services Sociaux: Windhoek, Namibia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Newfoundland and Labrador K-12 Education Re-Entry Plan; Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Quebec. Questions et Réponses sur L’éducation et la Famille dans le Contexte de la COVID-19; Government of Quebec: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yukon Education. School during COVID-19; Yukon Education: Whitehorse, YT, Cananda, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, L. Quebec’s COVID-19 Triage Protocol is Discriminatory, Disability Advocates Say; CBC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning. Guidance for Mask Use in Schools; Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning. Welcoming our Students Back: What Parents Need to Know; Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Saskatchewan. Primary and Secondary Educational Institution Guidelines; Government of Saskatchewan: Regina, SK, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- British Columbia Ministry of Health. COVID-19 Public Health Guidance for K-12 Schools; British Columbia Ministry of Health: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning. Welcoming Our Students Back: Supporting Students with Special Needs and Students at Risk as They Return to School; Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Alberta Department of Community and Social Services Disability Services. Guidance for Disability Services Providers Re-Opening or Continuing Operations; Government of Alberta Department of Community and Social Services Disability Services: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. COVID-19: Support for People; Government of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Prince Edward Island. Pre-Travel Approval Process; Government of Prince Edward Island: Charlottetown, PE, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Ministry of Children Community and Social Services. Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities; Ontario Ministry of Children Community and Social Services: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministere de la Sante et des services Sociaux. Guide de Réorganisation et de Délestage des Activités Selon les Niveaux D’alerte des Tablissements Direction Générale des Programmes Dédiés aux Personnes, aux Familles et aux Communautés; Ministere de la Sante et des services Sociaux: Windhoek, Namibia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Ahmed, R.; Moitra, M.; Damschroder, L.; Brownson, R.; Chorpita, B.; Idele, P.; Gohar, F.; Huang, K.Y.; Saxena, S.; et al. Mental Distress and Human Rights Violations During COVID-19: A Rapid Review of the Evidence Informing Rights, Mental Health Needs, and Public Policy around Vulnerable Populations. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 603875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Finlay, B.; Seth, A.; Roth, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Hudon, A.; Hunt, M.; Jodoin, S.; Lach, L.; Lencucha, R.; et al. Mental health challenges during COVID-19: Perspectives from parents with children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2022, 17, 2136090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of New Brunswick Family Supports for Children with Disabilities. Available online: https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/services/services_renderer.10195.Family_Supports_for_Children_with_Disabilities_.html (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Government of Alberta Family Support for Children with Disabilities (FSCD). Available online: https://www.alberta.ca/fscd.aspx (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Government of Ontario Children with Special Needs. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/children-special-needs (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Arim, R.; Findlay, L.; Kohen, D. The impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Canadian Families of Children with Disabilities. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00066-eng.htm (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Patel, K. Mental health implications of COVID-19 on children with disabilities. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, J.; Beauchamp, M.H.; Brown, C. The impact of COVID-19 on the learning and achievement of vulnerable Canadian children and youth. FACETS 2021, 6, 1693–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.; Yusuf, A.; Steiman, M.; Wright, N.; Karpur, A.; Shih, A.; Shikako-Thomas, K. The Global Report on Developmental Delays, Disorders and Disabilities-Canada. In Report Submitted to the Steering Group for the UNICEF and World Health Organization Global Report on Developmental Delays, Disorders and Disabilities; ChildBright Network: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, A.; Wright, N.; Steiman, M.; Gonzalez, M.; Karpur, A.; Shih, A.; Shikako, K.; Elsabbagh, M. Factors associated with resilience among children and youths with disability during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruskin, S.; Bogecho, D.; Ferguson, L. ‘Rights-based approaches’ to health policies and programs: Articulations, ambiguities, and assessment. J. Public Health Policy 2010, 31, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). General Comment No. 1 (2014), Article 12: Equal Recognition before the Law; CRPD/C/GC/1; UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J. A realistic approach to assessing mental health laws’ compliance with the UNCRPD. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2015, 40, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, F.B. The Error of Positive Rights. Ucla Law Rev. 2001, 48, 857–924. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Constitutional Studies. Positive and Negative Rights. Available online: https://www.constitutionalstudies.ca/2019/07/positive-and-negative-rights/ (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Sabatier, P.A. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Sci. 1988, 21, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P. From Policy Implementation to Policy Change: A Personal Odyssey. In Reform and Change in Higher Education: Analysing Policy Implementation; Gornitzka, Å., Kogan, M., Amaral, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 2005; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; A/RES/69/283; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman, A.R.; Stelk, W.; Horwitz, S.M.; Evans, M.E.; Outlaw, F.H.; Atkins, M. A public health approach to children’s mental health services: Possible solutions to current service inadequacies. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 37, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. A Rights-Based Approach to Disability in the Context of Mental Health; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Concluding Observations on the Initial Report of Canada; CRPD/C/CAN/CO/1. 2017; UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). General Comment No. 7 (2018) on the Participation of Persons with Disabilities, Including Children with Disabilities, through Their Representative Organizations, in the Implementation and Monitoring of the Convention; CRPD/C/GC/7.; UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M.Z.; Gusmano, M.K.; Maschke, K.J. The Ethical Imperative and Moral Challenges of Engaging Patients and the Public with Evidence. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Employment and Social Development Canada. COVID-19 Disability Advisory Group Report; Employment and Social Development Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR. COVID-19 and Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/covid-19-and-persons-disabilities (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Children First Canada. Raising Canada 2021: Top 10 Threats to Childhood in Canada: Recovering from the Impacts of COVID-19; Children First Canada: Calgary, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria: | If the policy follows all the inclusion criteria, please add YES, go to the next column, “Excluded”, add NO, and continue your data abstraction. If the policy does not follow the inclusion criteria, please add NO in the “Inclusion criteria” column and use the next column, “Excluded”, to add the rationale for exclusion (e.g., published in 2018 before the pandemic). Then, stop abstracting data from this policy as it would be excluded, and start with the next policy. |

| Policy type | Please use the dropdown menu to classify the policy. If the policy does not fit under the classification provided, select “other”. |

| Policy lever | Policy levers are mechanisms available to decision-makers to influence system changes. Please select from the dropdown menu (e.g., legislative, administrative, regulatory, and other). |

| Government level | Please add what level of government or institution will implement the policy (e.g., local, municipal, provincial and federal government). |

| Operational details | How does the policy work/operate? Please select from the dropdown menu: YES, if it is mandatory; NO, if it is not mandatory; and NR, if it is not reported. |

| Funding | Add information on how the policy is funded. If not funded, please add NO. If not reported, please add NR. |

| Policy goals | Please copy and paste the goals/objectives of the policy. |

| Context | Please add in which context the policy was created (e.g., out-of-pocket expenses with healthcare increased due to COVID-19; therefore, this policy was created to ensure….; historical context, such as the policy has been debated previously because….). This information usually is given in the introduction section. |

| Implementation mechanism | Please use the dropdown menu to select your answer (e.g., YES or NO) |

| Implementation mechanism details | If you selected YES in Q9, please copy and paste the implementation mechanism as reported by the authors (e.g., online counselling will be funded by the health ministry; and respite care workers will have priority in immunization to continue services supports for families). If you selected NO in Q9, add “NO” (please do not leave blank cells). |

| Short-term outcomes | Please add the expected short-term outcomes. |

| Intermediate-term outcomes | Please add the expected intermediate-term outcomes. |

| Long-term outcomes | Please add the expected long-term outcomes. |

| Costs | Please add any costs related to the policy. If not reported, add NO. |

| Location (n = 13) | Polices Included (n = 148) |

|---|---|

| British Columbia (BC) | 12 |

| Alberta (AB) | 10 |

| Saskatchewan (SK) | 3 |

| Manitoba (MB) | 26 |

| Ontario (ON) | 22 |

| Quebec (QC) | 38 |

| New Brunswick (NB) | 6 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) | 10 |

| Nova Scotia (NS) | 5 |

| Prince Edward Island (PEI) | 7 |

| New Territories (NT) | 3 |

| Nunavut (NV) | 1 |

| Yukon (YK) | 5 |

| Article | Themes Identified in Thematic Analysis (Only for Articles with Greater than 25 Frequency) | Provinces |

|---|---|---|

| Article 24: Education | Services provided in a school setting and intersectionality Considerations for alternative learning methods safety and training of school staff to continue education provisions during the pandemic | AB, BC, NL, NS, QC, SK, NU, YT |

| Article 11: Humanitarian Emergencies | Hygiene and preventative measures for institutions Funding and structural supports for institutions Specific needs of children. | BC, NB, NL, NS, SK, NU, NWT, YT |

| Article 19: Independent Living | Community service provisions Recommendations for educational settings | AB, BC, MB, NL, ON, PEI, QC, YT |

| Article 26: Habilitation and Rehabilitation | Rehabilitation programs offered in schools Establishment of alternative rehabilitation services | MB, NL, QC, YT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shikako, K.; Lencucha, R.; Hunt, M.; Jodoin-Pilon, S.; Chandra, A.; Katalifos, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; Cardoso, R.; Elsabbagh, M.; et al. Children with Disabilities in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of COVID-19 Policies through a Disability Rights Lens. Children 2023, 10, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060942

Shikako K, Lencucha R, Hunt M, Jodoin-Pilon S, Chandra A, Katalifos A, Gonzalez M, Yamaguchi S, Cardoso R, Elsabbagh M, et al. Children with Disabilities in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of COVID-19 Policies through a Disability Rights Lens. Children. 2023; 10(6):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060942

Chicago/Turabian StyleShikako, Keiko, Raphael Lencucha, Matthew Hunt, Sébastien Jodoin-Pilon, Ananya Chandra, Anna Katalifos, Miriam Gonzalez, Sakiko Yamaguchi, Roberta Cardoso, Mayada Elsabbagh, and et al. 2023. "Children with Disabilities in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of COVID-19 Policies through a Disability Rights Lens" Children 10, no. 6: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060942

APA StyleShikako, K., Lencucha, R., Hunt, M., Jodoin-Pilon, S., Chandra, A., Katalifos, A., Gonzalez, M., Yamaguchi, S., Cardoso, R., Elsabbagh, M., Hudon, A., Martens, R., Cogburn, D., Seth, A., Currie, G., Roth, C., Finlay, B., & Zwicker, J. (2023). Children with Disabilities in Canada during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of COVID-19 Policies through a Disability Rights Lens. Children, 10(6), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060942