Association between Dentofacial Features and Bullying from Childhood to Adulthood: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Sources of Information and Search Strategy

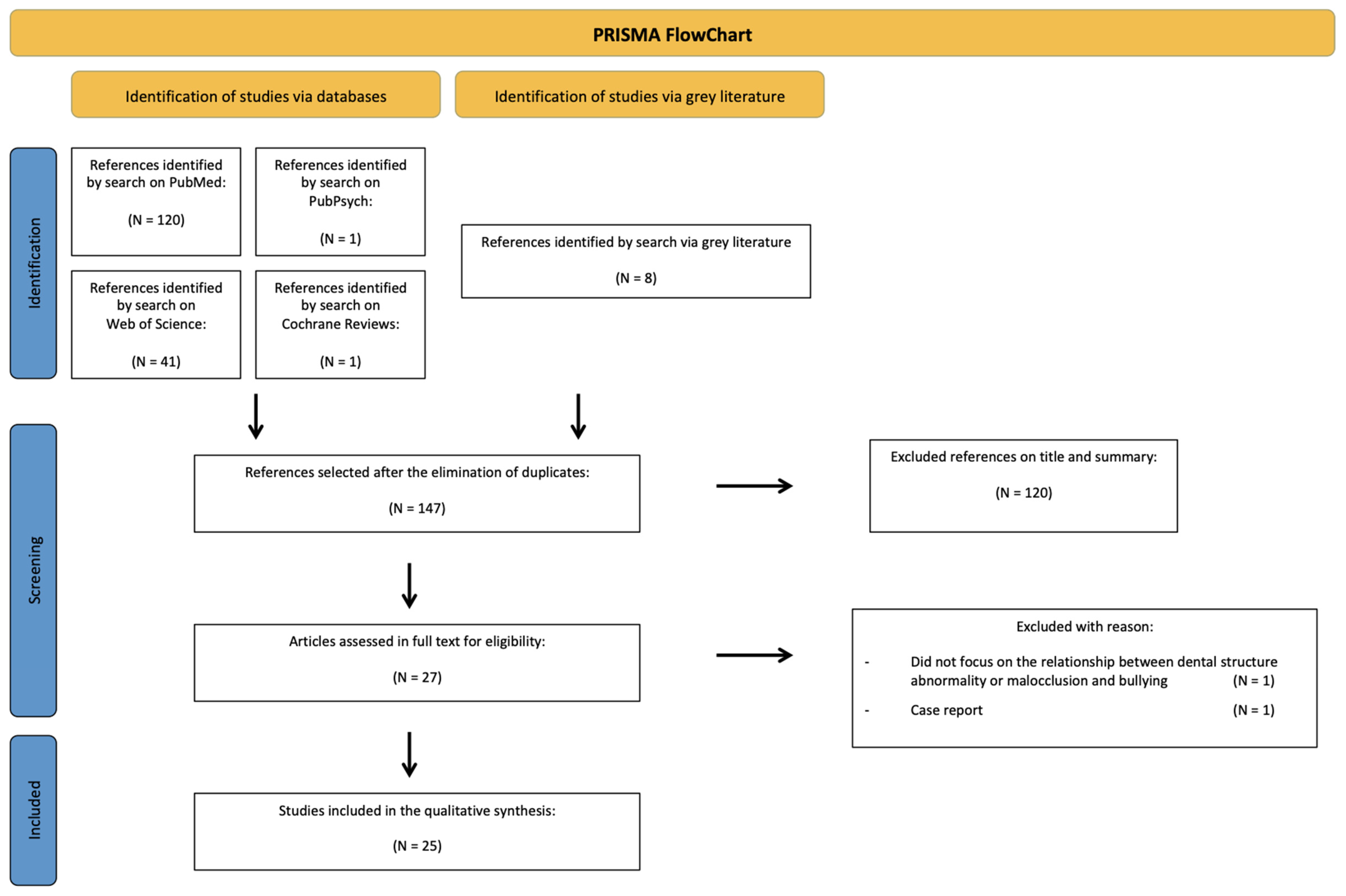

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

3.3. Identification of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olweus, D. Bullying at School: Basic Facts and Effects of a School Based Intervention Program. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1994, 35, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olweus, D. Victimisation by Peers: Antecedents and Long-Term Outcomes. In Social Withdrawal, Inhibition and Shyness in Childhood; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Van Cruchten, C.; Feijen, M.M.W.; van der Hulst, R.R.W.J. The Perception of Esthetic Importance of Craniofacial Elements. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2022, 33, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; McGrath, C.; Hägg, U. The Impact of Malocclusion and Its Treatment on Quality of Life: A Literature Review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2006, 16, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukra, A.; Bennani, F.; Farella, M. Psychological Aspects of Orthodontics in Clinical Practice. Part Two: General Psychosocial Wellbeing. Prog. Orthod. 2012, 13, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, L.; Aleksieva, A.; Willems, G.; Declerck, D.; Cadenas de Llano-Pérula, M. Prevalence of Orthodontic Malocclusions in Healthy Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, R.C.J.; Garbin, A.J.Í.; Corrente, J.E.; Garbin, C.A.S. The Relationship between Oral Health-Related Quality of Life, the Need for Orthodontic Treatment and Bullying, among Brazilian Teenagers. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2019, 24, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanko, O.M.E.; Svedström-Oristo, A.-L.; Peltomäki, T.; Kauko, T.; Tuomisto, M.T. Psychosocial Well-Being of Prospective Orthognathic-Surgical Patients. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2014, 72, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.T.M.; Nabarrette, M.; Vedovello-Filho, M.; de Menezes, C.C.; Meneghim, M.d.C.; Vedovello, S.A.S. Correlation between Malocclusion and History of Bullying in Vulnerable Adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.C.-C.; Simmer, J.P. Developmental Biology and Genetics of Dental Malformations. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 2007, 10, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Dure-Molla, M.; Fournier, B.P.; Manzanares, M.C.; Acevedo, A.C.; Hennekam, R.C.; Friedlander, L.; Boy-Lefèvre, M.-L.; Kerner, S.; Toupenay, S.; Garrec, P.; et al. Elements of Morphology: Standard Terminology for the Teeth and Classifying Genetic Dental Disorders. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2019, 179, 1913–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousette Lundgren, G.; Karsten, A.; Dahllöf, G. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life before and after Crown Therapy in Young Patients with Amelogenesis Imperfecta. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atik, E.; Önde, M.M.; Domnori, S.; Tutar, S.; Yiğit, O.C. A Comparison of Self-Esteem and Social Appearance Anxiety Levels of Individuals with Different Types of Malocclusions. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2021, 79, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akpasa, I.O.; Yemitan, T.A.; Ogunbanjo, B.O.; Oyapero, A. Impact of Severity of Malocclusion and Self-Perceived Smile and Dental Aesthetics on Self-Esteem among Adolescents. J. World Fed. Orthod. 2022, 11, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, V.M.R.; Golm, D.; Juhl, J.; Sajid, S.; Brandt, V. The Relationship between Peer Victimisation, Self-Esteem, and Internalizing Symptoms in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Tools—JBI. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 19 May 2023).

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda e Paulo, D.; Navarro de Oliveira, M.; de Andrade Vieira, W.; Flores-Mir, C.; Pithon, M.M.; Bittencourt, M.A.V.; Paranhos, L.R. Impact of Malocclusion on Bullying in School Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 142, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.; Kreiborg, S.; Solow, B. Psychosocial Implications of Malocclusion: A 15-Year Follow-up Study in 30-Year-Old Danes. Am. J. Orthod. 1985, 87, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, G.; Morales, F.; Gamboa, L.; Meza, A.M.; López, A.C. Impacto emocional y en calidad de vida de individuos afectados por amelogénesis imperfecta. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2015, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdulrazaq, R.S.; Al-Haj Ali, S.N. Parental Reported Bullying among Saudi Schoolchildren: Its Forms, Effect on Academic Abilities, and Associated Sociodemographic, Physical, and Dentofacial Features. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020, 2020, 8899320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pousette Lundgren, G.; Hasselblad, T.; Johansson, A.; Johansson, A.; Dahllöf, G. Experiences of Being a Parent to a Child with Amelogenesis Imperfecta. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpeläinen, P.V.; Phillips, C.; Tulloch, J.F. Anterior Tooth Position and Motivation for Early Treatment. Angle Orthod. 1993, 63, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanch, K.; Antoun, J.; Smith, L.; Jack, H.; Fowler, P.; Page, L.F. Considering Malocclusion as a Disability. Australas. Orthod. J. 2019, 35, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, W.C.; Meek, S.C.; Jones, D.S. Nicknames, Teasing, Harassment and the Salience of Dental Features among School Children. Br. J. Orthod. 1980, 7, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Antoun, J.S.; Morgaine, K.C.; Farella, M. Accounts of Bullying on Twitter in Relation to Dentofacial Features and Orthodontic Treatment. J. Oral Rehabil. 2017, 44, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bitar, Z.B.; Al-Omari, I.K.; Sonbol, H.N.; Al-Ahmad, H.T.; Cunningham, S.J. Bullying among Jordanian Schoolchildren, Its Effects on School Performance, and the Contribution of General Physical and Dentofacial Features. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2013, 144, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Omari, I.K.; Al-Bitar, Z.B.; Sonbol, H.N.; Al-Ahmad, H.T.; Cunningham, S.J.; Al-Omiri, M. Impact of Bullying Due to Dentofacial Features on Oral Health–Related Quality of Life. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehra, J.; Newton, J.T.; DiBiase, A.T. Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Bullied Adolescents and Its Impact on Self-Esteem and Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life. Eur. J. Orthod. 2013, 35, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehra, J.; Fleming, P.S.; Newton, T.; DiBiase, A.T. Bullying in Orthodontic Patients and Its Relationship to Malocclusion, Self-Esteem and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life. J. Orthod. 2011, 38, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikaodi, O.; Abdulmanan, Y.; Emmanuel, A.T.; Muhammad, J.; Mohammed, M.A.; Izegboya, A.; Donald, O.O.; Balarabe, S. Bullying, Its Effects on Attitude towards Class Attendance and the Contribution of Physical and Dentofacial Features among Adolescents in Northern Nigeria. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2019, 31, 20160149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruitero, M.J.; Julca-Ching, K. Impact of the Need for Orthodontic Treatment on Academic Performance, Self-Esteem and Bullying in Schoolchildren. J. Oral Res. 2019, 8, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Rodrigues, L.; Ramos-Jorge, M.L.; Alves-Duarte, A.C.; Fonseca-Silva, T.; Flores-Mir, C.; Marques, L.S. Oral Disorders Associated with the Experience of Verbal Bullying among Brazilian School-Aged Children. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 151, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán-Serrano, M.; Carruitero, M.J. Assessment of General Bullying and Bullying Due to Appearance of Teeth in a Sample of 11–16 Year-Old Peruvian Schoolchildren. J. Oral Res. 2017, 6, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros Donohue, M.; Barrientos Achata, A. Incidencia y factores de riesgo de la intimidación (bullying) en un colegio particular de Lima-Perú. Rev. Peru. Pediatr. 2007, 60, 150–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rwakatema, D.S.; Ng’ang’a, P.M.; Kemoli, A.M. Awareness and Concern about Malocclusion among 12–15 Year-Old Children in Moshi, Tanzania. East Afr. Med. J. 2006, 83, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng’ang’a, P.M.; Stenvik, A.; Ohito, F.; Ogaard, B. The Need and Demand for Orthodontic Treatment in 13- to 15-Year-Olds in Nairobi, Kenya. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1997, 55, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaso, C.O.; Sanu, O.O. Psychosocial Implications of Malocclusion among 12–18 Year Old Secondary School Children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Odonto-Stomatol. Trop. Trop. Dent. J. 2005, 28, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bauss, O.; Vassis, S. Prevalence of Bullying in Orthodontic Patients and Its Impact on the Desire for Orthodontic Therapy, Treatment Motivation, and Expectations of Treatment. J. Orofac. Orthop. Fortschr. Kieferorthopädie 2023, 84, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.S.; Proczek, K.; DiBiase, A.T. I Want Braces: Factors Motivating Patients and Their Parents to Seek Orthodontic Treatment. Community Dent. Health 2008, 25, 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sujak, S.L.; Kadir, R.A.; Dom, T.N.M. Esthetic Perception and Psychosocial Impact of Developmental Enamel Defects among Malaysian Adolescents. J. Oral Sci. 2004, 46, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga da Silva Siqueira, D.; dos Santos, I.M.; Pereira, L.L.; Leal Tosta dos Santos, S.C.; Cristino, P.S.; Pena Messias de Figueiredo Filho, C.E.; Figueiredo, A.L. Impact of Oral Health and Body Image in School Bullying. Spec. Care Dent. 2019, 39, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tristão, S.K.P.C.; Magno, M.B.; Pintor, A.V.B.; Christovam, I.F.O.; Ferreira, D.M.T.P.; Maia, L.C.; de Souza, I.P.R. Is There a Relationship between Malocclusion and Bullying? A Systematic Review. Prog. Orthod. 2020, 21, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menesini, E.; Salmivalli, C. Bullying in Schools: The State of Knowledge and Effective Interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, D.M. Childhood Bullying, Teasing, and Violence: What School Personnel, Other Professionals, and Parents Can Do, 2nd ed.; American Counseling Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1-55620-196-7. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypiec, G.; Alinsug, E.; Nasiruddin, U.A.; Andreou, E.; Brighi, A.; Didaskalou, E.; Guarini, A.; Kang, S.-W.; Kaur, K.; Kwon, S.; et al. Self-Reported Harm of Adolescent Peer Aggression in Three World Regions. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 85, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffel, D.L.S.; Jeremias, F.; Fragelli, C.M.B.; dos Santos-Pinto, L.A.M.; Hebling, J.; de Oliveira, O.B. Esthetic Dental Anomalies as Motive for Bullying in Schoolchildren. Eur. J. Dent. 2014, 8, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehra, J.; Newton, J.T.; DiBiase, A.T. Bullying in Schoolchildren—Its Relationship to Dental Appearance and Psychosocial Implications: An Update for GDPs. Br. Dent. J. 2011, 210, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBiase, A.T.; Sandler, P.J. Malocclusion, Orthodontics and Bullying. Dent. Update 2001, 28, 464–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bitar, Z.B.; Sonbol, H.N.; Al-Omari, I.K.; Badran, S.A.; Naini, F.B.; Al-Omiri, M.K.; Hamdan, A.M. Self-Harm, Dentofacial Features, and Bullying. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. Off. 2022, 162, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | 1. Is There Congruity between the Stated Philosophical Perspective and the Research Methodology? | 2. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Research Question or Objectives? | 3. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Methods Used to Collect Data? | 4. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Representation and Analysis of Data? | 5. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Interpretation of Results? | 6. Is There a Statement Locating the Researcher Culturally or Theoretically? | 7. Is the Influence of the Researcher on the Research, and Vice-versa, Addressed? | 8. Are Participants, and Their Voices, Adequately Represented? | 9. Is the Research Ethical According to Current Criteria or for Recent Studies, and Is There Evidence of Ethical Approval by an Appropriate Body? | 10. Do the Conclusions Drawn in the Research Report Flow from the Analysis or Interpretation of the Data? | TOT | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanch 2019 [25] | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6.5 | 65% |

| Chan 2017 [27] | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 50% |

| Pousette Lundgren 2019 [23] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 100% |

| Shaw 1980 [26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9.5 | 95% |

| Authors | 1. Were the Criteria for Inclusion in the Sample Clearly Defined? | 2. Were the Study Subjects and the Setting Described in Detail? | 3. Was the Exposure Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 4. Were Objective, Standard Criteria Used for Measurement of the Condition? | 5. Were Confounding Factors Identified? | 6. Were Strategies to Deal with Confounding Factors Stated? | 7. Were the Outcomes Measured in a Valid and Reliable Way? | 8. Was Appropriate Statistical Analysis Used? | TOTAL | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Bitar 2013 [28] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 63% |

| Al Omari 2014 [29] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 75% |

| Alabdulrazaq 2020 [22] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 63% |

| Alanko 2014 [8] | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6.5 | 81% |

| Bauss 2023 [40] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 75% |

| Bazan-Serrano 2017 [35] | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.5 | 69% |

| Chikaodi 2019 [32] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 50% |

| Duarte Rodrigues 2020 [34] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 100% |

| Fleming 2008 [41] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 63% |

| Gatto 2019 [7] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 | 81% |

| Helm 1985 [20] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 56% |

| Carruitero 2019 [33] | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5.5 | 69% |

| Kilpeläinen 1993 [24] | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 38% |

| Murillo 2015 [21] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 38% |

| Onyeaso 2005 [39] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 50% |

| Ramos 2022 [9] | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4.5 | 56% |

| Rwakatema 2006 [37] | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 31% |

| Seehra 2011 [31] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 75% |

| Seehra 2013 [30] | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 6 | 75% |

| Sujak 2004 [42] | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.5 | 69% |

| Veiga Da Silva Siqueira 2019 [43] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 38% |

| Authorship Year of Publication | Country and Date of Study | Participants | Oral Condition Assessed | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age Range | Inclusion Origin | ||||

| Blanch et al., 2019 [25] | New Zealand 2012–2015 | 292 letters (143 from caregivers, 149 from young people) 18 young people interviews | 11–18 years | “Wish for a Smile” New Zealand program | Malocclusion | 53% of young people’s letters, 92.3% of treated participants’ interviews and 100% of untreated participants’ interviews talked about bullying and negative comments pre-treatment. |

| Chan et al., 2017 [27] | No geographic restriction 2010–2014 | 321 Twitter posts | - | Morphological features of teeth (malocclusion, braces and orthodontic appliances, personal attributes or personality traits) | Social media can provide new and valuable information about the causal factors and social issues associated with oral health-related bullying. Importantly, some coping mechanisms may mitigate the negative effects of bullying. | |

| Pousette Lundgren et al., 2019 [23] | Sweden 2015 | 8 interviews with parents | Parents of children 9–18 years old | Public dental service and paediatric dentistry clinic | Amelogenesis imperfecta | The subtheme “psychosocial stress” included fear of the child being bullied. The findings show that parents of children with severe amelogenesis imperfecta report similar experiences as parents of children with other chronic and rare diseases. |

| Shaw et al., 1980 [26] | Wales NS | STUDY 1 531 interviews with children Teachers’ questionnaires | 9–13 years | Schools | Features targeted in the victims of bullying. | Dental features were the fourth commonest target for teasing. Seven per cent of the total sample reported being teased about their teeth once per week or more. Comments about the teeth appear to be more hurtful than those about other features. Children who were teased specifically about their teeth were twice as likely to suffer harassment than those who were not teased about their teeth. |

| STUDY 2 82 children | 11–13 years | Schools | Features targeted in the victims of bullying by nickname. | The more deviant the dental arrangement, the more salient will it be. | ||

| Authorship Year of Publication | Country and Date of Study | Participants | Oral Condition Assessed | Oral Condition Assessment | Bullying Assessment | Additional Characteristics Assessed | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age Range | Inclusion Origin | |||||||

| Al Bitar et al., 2013 [28] | Jordan 2011–2012 | 920 | 11–12 years | Schools | Dentofacial features targeted in the victims of bullying | Structured, anonymous, self-reported questionnaire modified from that of Shaw et al., (1980) | Same questionnaire modified from that of Shaw et al., (1980) | General physical characteristics targeted in the victims of bullying. Feelings toward school and school attendance. Perceived effect on academic performance. | Teeth were the number 1 feature targeted for bullying. The three most commonly reported dentofacial features targeted by bullies: spacing between the teeth or missing teeth, shape or colour of the teeth, and prominent maxillary anterior teeth. |

| Al Omari et al., 2014 [29] | Jordan 2011–2012 | 920 | 11–12 years | Schools | Dentofacial features targeted in the victims of bullying | Structured, anonymous, self-reported questionnaire modified from that of Shaw et al., (1980) | Same questionnaire modified from that of Shaw et al., (1980) | General physical characteristics targeted in the victims of bullying, Feelings toward school and school attendance. Perceived effect on academic performance. | There was a significant relationship between bullying because of dentofacial features and negative effects on oral health–related quality of life. |

| Alabdulrazaq and Al-Haj Ali 2020 [22] | Saudi Arabia 2019–2020 | 1028 | Parents of children 8–18 years old | Social networks | Dentofacial features targeted in the victims of bullying as reported by parents | Self-reported questionnaire modified from that of Al Bitar et al., (2013) | Same questionnaire was modified from that of Al Bitar et al., (2013). | Sociodemographic profile. Parental opinion about the effect of bullying on their child’s feelings toward school and on school attendance. Bullying’s perceived effect on academic performance. General physical characteristics targeted in the victims of bullying. | With regard to targeted physical features, teeth were the number one target. Tooth shape and colour were the most common dentofacial targets, followed by an anterior open bite and protruded anterior teeth. |

| Alanko et al., 2014 [8] | Finland NS | 89 (60 patients/29 controls) | 17–61 years (patients 17–61 years/controls 19–49 years) | Study group: oral and maxillo-facial services/control group: university students | Dental appearance | -Patients’ self-evaluation of dental appearance on a visual analogue scale modified from the Aesthetic Component of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN-AC). -Professional assessment of patients’ dental appearance with the IOTN-AC. | A structured diary developed by the authors | A modified version of the body image questionnaire (Kiyak 1982), Orthognathic Quality-of-Life. Questionnaire (Cunningham 2000) (OQLQ) Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg 1965) (RSES). Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II (Bond 2011) (AAQ II) Symptom Checklist 90 (Derogatis 1973) (SCL-90). | 15% of the patients had been bullied. Self-perceived dental appearance was more important to orthognathic quality-of-life and body image than an orthodontist’s assessment. |

| Bauss and Vassis 2021 [40] | Germany 2015–2019 | 1020 | 7–17 years | Orthodontic practices | Dentofacial features targeted in the victims of bullying | Anonymous questionnaires | Anonymous questionnaires | Initiator of treatment, desire for orthodontic treatment, treatment motivation, treatment expectations, and general physical characteristics targeted in the victims of bullying. | Bullied subjects identified teeth and weight as the main targets for bullying. Victims who experienced bullying due to malocclusion initiate orthodontic treatment more often themselves and expect therapy to prevent them from experiencing further bullying. |

| Bazan-Serrano and Carruitero 2017 [35] | Peru NS | 218 | 11–16 years | Schools | Appearance of teeth/targeted by bullying | Question from Al Bitar et al., questionnaire (2013) | Validated questionnaire (from Oliveros et al.) | - | The frequency of general bullying was 32.57%, and bullying due to dental appearance was 18.81%. General and tooth-related bullying was more frequent among students in public schools. |

| Chikaodi et al., 2017 [32] | Nigeria 2016 | 835 | 12–17 years | Schools | Dentofacial features targeted in the victims of bullying | Structured anonymous self-administered questionnaire modified from that used by Al Bitar et al., (2013) | Same questionnaire was modified from that used by Al Bitar et al., (2013). | -General physical characteristics targeted in the victims of bullying. -Feelings toward school and school attendance. -Perceived effect on grades. | About 43% of respondents reported being victims of bullying, while about 32% had bullied someone else. Bullies frequently targeted general physical and dentofacial appearance. |

| Duarte Rodrigues et al., 2020 [34] | Brazil NS | 390 | 8–10 years | Schools | -Malocclusion -Dental fluorosis -Developmental Defects of Enamel | -Dental Aesthetics Index (DAI) -Modified Dean index -Modified Developmental Defects of Enamel index | One question from the CPQ-8-10 index | -Untreated caries: DMFT/dmft. -Clinical consequences of untreated caries: PUFA/pufa. | A severe malocclusion, a greater maxillary misalignment and the presence of a tooth with pulp exposure were significantly associated with the occurrence of verbal bullying. |

| Fleming et al., 2008 [41] | United Kingdom 2003–2004 | 328 | 8–17 years or over | Orthodontic department | Appearance of teeth targeted by bullying | Children and parents’ anonymous questionnaires | Children and parents’ anonymous questionnaires | Motivation, understanding and expectation of orthodontic treatment | 38% reported teasing related to their dental appearance (of these, only 10% were untroubled by the teasing). Teasing was a commonly reported consequence of malocclusion with a negative psychosocial impact. |

| Gatto et al., 2019 [7] | Brazil 2014 | 815 | 11–16 years | Schools | Malocclusion | DAI | Kidscape questionnaire | -Oral Health related Quality of Life: OHIP-14. -Previous orthodontic treatment. -Desire to fix the teeth to improve one’s appearance. | The need for orthodontic treatment was not associated with the OHRQoL; however, bullying and previous orthodontic treatment had a statistically significant association with this variable. |

| Helm et al., 1985 [20] | Denmark 1981 | 758 (maloc-clusion: 606/normoc-clusion: 152) | 13–19 years when the occurrence of malocclusion was recorded/28–34 years when question-naires sent | Schools | Malocclusion Dental appearance | Questionnaire | Questionnaire | Orthodontic treatment. Functional disorders. Tooth loss. Body image. | Schoolmates’ teasing occurred seven times more often in the presence of malocclusion. |

| Carruitero and Julca-Ching 2019 [33] | Peru NS | 147 | 12–18 years | Schools | Need for orthodontic treatment | DAI | Questionnaire from Al Bitar (2013) | -Self esteem: Rosenberg test. | The need for orthodontic treatment in schoolchildren showed no impact on academic performance, self-esteem and bullying. The need for orthodontic treatment did not prove to be a determining factor in the presence of such variables in schoolchildren. |

| Kilpeläinen et al., 1993 [24] | USA 1989–1990 | 313 | Parents of children under 16 years | Orthodontic clinic | Overjet Alignment | Professional assessment | Self-reported questionnaire | Initiator of treatment, treatment motivation. | 44% of the parents reported their child had been teased about the appearance of their teeth. Overjet and misalignment were observed to be significant predictors of the parent’s report of the child being teased. |

| Murillo et al,. 2015 [21] | Costa Rica NS | 18 | 16–35 years | Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Costa Rica | Amelogenesis Imperfecta | Professional diagnostic | Questionnaire | Emotional aspect and dental treatment. | 100% had been teased and had suffered social rejection. Dental professionals need to understand AI not only as defective tooth enamel structures demanding specialist clinical management but also the negative impacts of the condition on the lives of their patients. |

| Onyeaso and Sanu 2005 [39] | Nigeria NS | 614 (malocclusion: 279/normocclusion: 335) | 12–18 years | Schools | -Malocclusion -Dental appearance | -DAI -Questionnaire | Questionnaire modified from Helm (1985) | Body image | Teasing had no significant difference between the two groups [without malocclusion vs with malocclusion]. Teasing was mostly reported for the following traits: anterior maxillary irregularity, midline diastema, crowding (maxillary and mandibular segments) and spacing (maxillary and mandibular segments). |

| Ramos et al., 2022 [9] | Brazil NS | 494 | 12–15 years | Schools | -Self-perceived need for orthodontic treatment -Malocclusion | -IOTN-AC -DAI | Questionnaire used in the National Survey of School Health (PeNSE) | -Socioeconomic conditions -Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (CPQ11–14) | Malocclusion did not correlate with bullying history. However, increased maxillary overjet influences adolescent self-perception, suggesting a potential condition for bullying events. |

| Rwakatema et al., 2006 [37] | Tanzania NS | 298 | 12–15 years | Schools | Dentofacial features | Self-administered questionnaires from Ng’ang’a et al. | Self-administered questionnaires from Ng’ang’a et al. | - | 25.8% of the children reported having been teased due to their malocclusion. |

| Seehra et al., 2011 [31] | United Kingdom 2007–2008 | 336 | 10–14 years | Orthodontic clinics | Orthodontic treatment need | -IOTN-DHC -IOTN-AC | Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire | -Self-esteem (Harter’s Self Perception Profile for Children) -Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (CPQ11–14) | The prevalence of bullying was 12.8%. Being bullied was significantly associated with Class II Division 1 incisor relationship, increased overbite, increased overjet and a high need for orthodontic treatment assessed using AC IOTN. Significant relationships also exist between bullying, self-esteem and OHRQoL. |

| Seehra et al., 2013 [30] | United Kingdom 2010–2011 | 27 | Mean age: 14.6 years, standard deviation 1.5 | Orthodontic clinic | Orthodontic treatment need | -IOTN-DHC -IOTN-AC | Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire | -Self-esteem (Harter’s Self Perception Profile for Children) -Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (CPQ11–14) | Following the commencement of orthodontic treatment, 21 (78 %) participants reported they were currently no longer being bullied due to the presence of their malocclusion. Orthodontic treatment may have a positive effect on adolescents experiencing bullying related to their malocclusion and their OHRQoL. |

| Sujak et al., 2004 [42] | Malaysia NS | 1024 | 16 years | Schools | Developmental defects of enamel | Modified Developmental Defects of Enamel Index (FDI, 1992) | Self-administered questionnaire | - | About two-thirds of the sample (67.1%) had at least one tooth affected by enamel defects. Only 5.7% had experienced being teased by their friends about the problem. |

| Veiga Da Silva Siqueira et al., 2019 [43] | Brazil NS | 381 | 12–15 years | Schools | Self-perception about oral health | Questionnaire | Questionnaire | Self-perception about body image (questionnaire) | The prevalence of bullying was 29.6%. Those who indicated that they were criticised due to the condition of their teeth had a 4.37 times greater chance of victimisation. Those who felt that oral health had little effect on their relationship with other people had a 2.2 times greater chance of suffering from bullying than those who did not. It was possible to observe an association between bullying and dissatisfaction with oral health and body image. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Broutin, A.; Blanchet, I.; Canceill, T.; Noirrit-Esclassan, E. Association between Dentofacial Features and Bullying from Childhood to Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10, 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060934

Broutin A, Blanchet I, Canceill T, Noirrit-Esclassan E. Association between Dentofacial Features and Bullying from Childhood to Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Children. 2023; 10(6):934. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060934

Chicago/Turabian StyleBroutin, Alice, Isabelle Blanchet, Thibault Canceill, and Emmanuelle Noirrit-Esclassan. 2023. "Association between Dentofacial Features and Bullying from Childhood to Adulthood: A Systematic Review" Children 10, no. 6: 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060934

APA StyleBroutin, A., Blanchet, I., Canceill, T., & Noirrit-Esclassan, E. (2023). Association between Dentofacial Features and Bullying from Childhood to Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Children, 10(6), 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060934