The Therapeutic Aspects of Embroidery in Art Therapy from the Perspective of Adolescent Girls in a Post-Hospitalization Boarding School

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Embroidery

1.2. Embroidery in Art Therapy

1.3. Mental Health Challenges Faced by Adolescent Girls: Understanding and Addressing the Issues

1.4. Out-of-Home Art Therapy That Addresses Mental Health Challenges in Adolescents

2. Method

2.1. The Research Approach

2.2. Participants

2.3. The Research Process

2.3.1. The Embroidery Session at the Open Studio Post-Hospitalization Boarding School

2.4. The YPAR Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

3. Findings

3.1. The Dialectic between Control and Release/Freedom: Use of Patterns as Opposed to Freestyle Embroidery

“The liberty I took when working with the cat is a recent development. Two years ago, when I started embroidering in the hospital, it took a long time before I even agreed to try. At first, I mostly used patterns for my projects. Later, I began choosing patterns for inspiration and sometimes ventured to create my designs. Ultimately, I started doing what I wanted. It was a process to get to this level of liberty.”

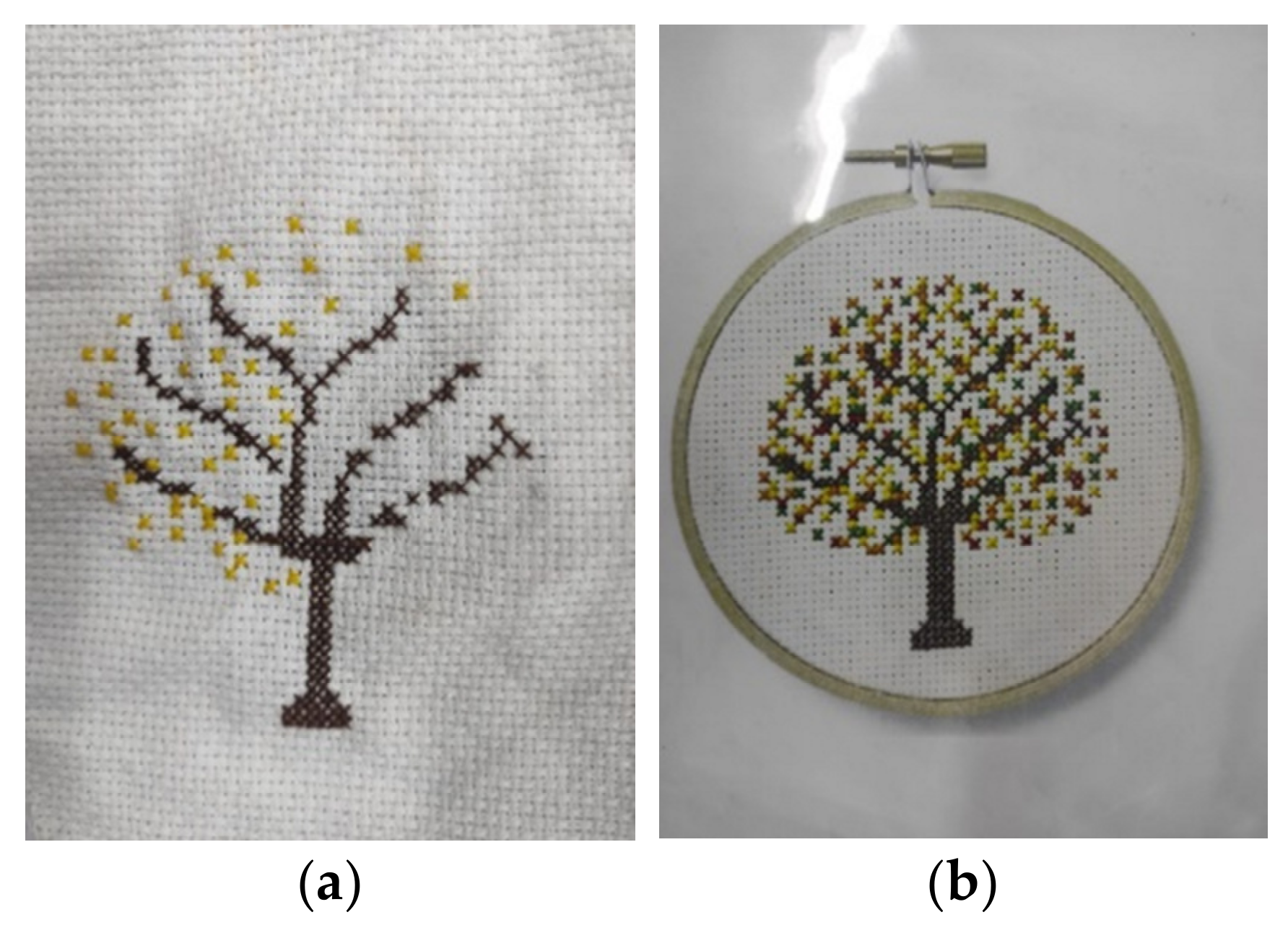

“I believe there’s a significant difference between cross stitching and freestyle embroidery. When doing cross-stitching, there are clear instructions on where to insert the needle and how to pull the thread. It can be easier in some ways because you know what you’re supposed to do. In the hospital, kids follow examples in books or use fabric with printed cross-stitch patterns, which makes it easier because then there are clear guidelines. But freestyle embroidery is more open-ended and there’s no set pattern to follow. For example, when I was working on the tree leaves, there were colorful flowers on the tree and it was difficult to know where to put them. The art therapists didn’t provide clear instructions and that was discouraging.”

“Listen, menstruation is not something that is neat and organized, is it? So obviously the stitches there on the pad that she sewed are not neat and organized either.”

“You can express everything here {in the group-W.N}, like embroidering on a pad, on a floor rag […]. It was really cool, like it’s not something normal, so to speak. As if you can do with it (embroidery) what you want. We had this activity of making each a small square. I just scribbled on mine. And I also wrote the “meow” {A cat’s mew from a children’s TV show-W.N} upside down, oh my, it’s terrible. And it is, for example, very inaccurate. But I had fun doing it too, it was wild to do such a thing. It was the opposite of doing the correct thing, I just went with the flow. It’s wild like that and it was cool.”

3.2. Calming—Repetitive, Focusing Action

“It’s very relaxing. {embroidery-W.N} Both the repeated action and focusing on one thing for a long time is very relaxing, it’s pausing everything and lets one focus on one thing.”Participant 5 (interview)

“Physically, it’s something fun to touch and mess with, it’s soft and cozy, and it’s comforting, and its touch calms a lot of people… The “click” of the needle, the sound of the needle moving through the fabric, it relaxes me, like white noise, like the sound of a waterfall.”Participant 9 (interview)

“I get into the zone, I am with myself, maybe it’s kind of pausing for a moment, from the day for something that is relaxing, some kind of situation with yourself… and we sit in a circle around the table, and it’s, like, it kind of focuses the group because everyone gets into some kind of similar mood…There are distractions in today’s culture, lots and lots of external things that interfere with our ability to take a second, to stop for a moment.”Participant 1 {While embroidering-W.N}

3.3. Being Exceptional versus Conventional

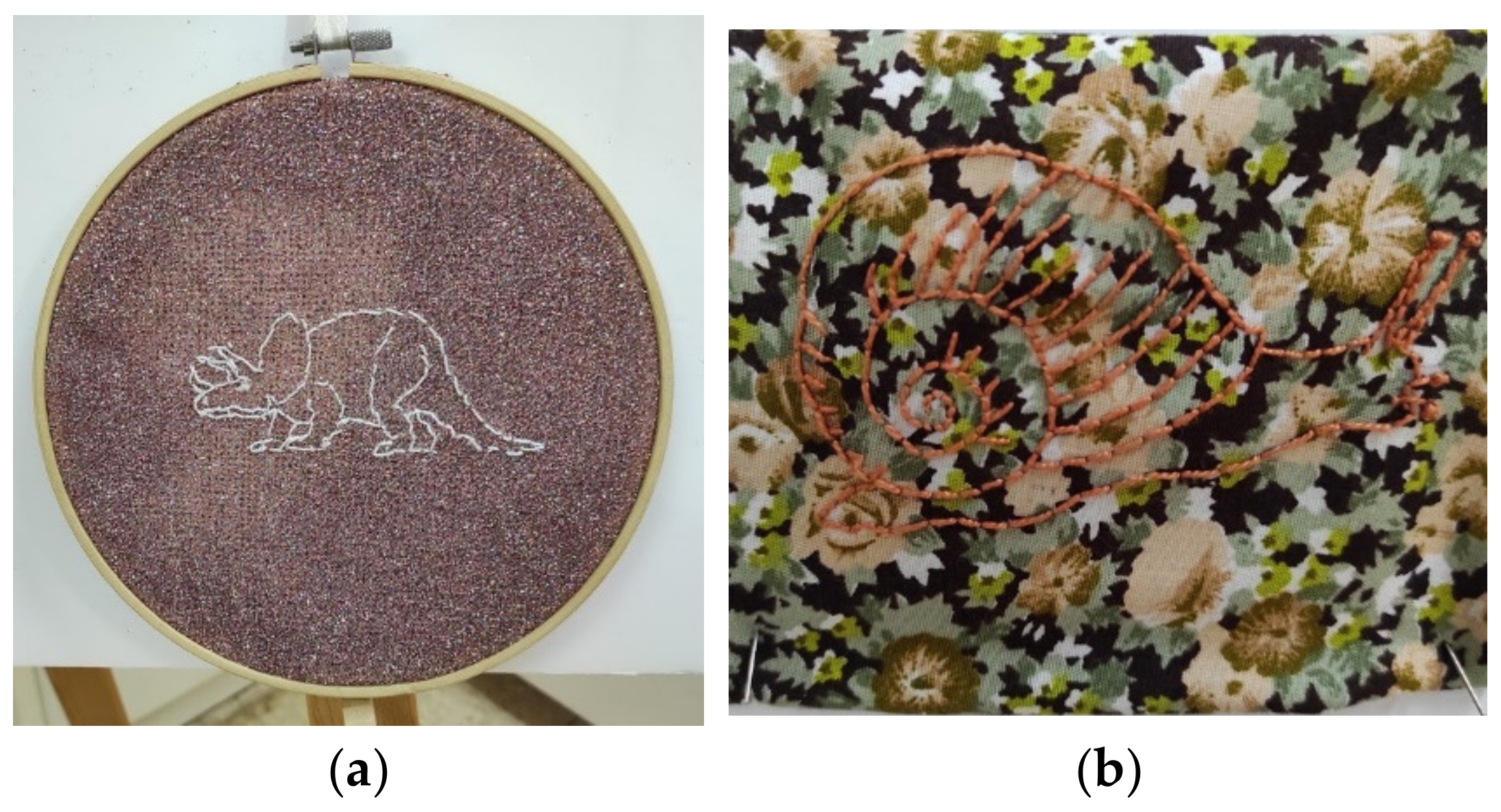

“I love animals and the combination of snails on a flowery, glittery background seems weird, but in a good way. Weird—nice because it’s the glitter fabric. It’s fun for me that it doesn’t connect. As if there is this game between a very specific thread and a very specific substrate of mine. It’s like everywhere I’ve been I’ve been a “different thread” in a “different substrate”, sometimes it connected well, sometimes it looked cool and sometimes it didn’t.”

“It was a special group. There were, absolutely, girls who came here and they didn’t stop until they got something perfect, absolutely, it’s like that with a lot of people in general. But here it is something that preoccupies us, mainly because perhaps we come from a background that made us more sensitive. I think we are very, very sensitive girls. We exhibit more sensitivity than other people. The sensitivity is very noticeable. Because I pay attention to every very small detail, I am sensitive to everything. Every terribly small detail seems bigger to me than to other people. Like in embroidery.”

“Because embroidering is “odd,” it is also the thing that makes it more special. Because it is valued. For example, it is rarer and more unique to see a greeting card in a store with embroidery on it, compared to a greeting card with a drawing on it. People see boarding schools as something (negative) different and strange, because most of the boarding schools you hear about are for teenagers who were kicked out of the house. This boarding school framework is unconventional.”

3.4. Stitch through Time—A Dialogue with the Past, Present, and Future

“I think that the repetitive and sisyphean process of embroidery is similar to those things we do repetitively where we may not always feel like we are making progress even though we are. I again compare it to the soul like going to therapy say once a week and again and again and again. And in the end, step by step, each treatment is like a stitch, in the end there is progress. There is progress at the end.”

“Embroidery is an activity that belongs to a time from many years ago, women used to do it. I think it’s worthy of appreciation, that I’m 17 and I embroider, wow, nice, I want to see more 17-year-old girls embroider. I don’t think it’s something that is commonly done in our times, today. There is no 17 years old girl who suddenly wakes up in the morning and says “Wow, I want to embroider.”

“You know that you have an hour like that, and you know that it {the embroidery W.N} relaxes you, and it does you good, it is good to take this break in the day. It’s such a pause […] and then concentrating on one thing. Chasing after money… I’m talking about life that isn’t really related to the boarding school. I’m talking about life in general: The pressure, the school system, feeling busy, pressure, the responsibility on children, family. Sometimes you need to breathe. There are many people who need this break. Maybe that’s (embroidery) what helps you to calm down, that focuses you that allows you to be centered.”

“And now you’ve stopped for commercials, wait—we’ll immediately return to the podcast of “Nurit of the Future”, Nurit, when you’ll edit it and listen to it, good luck, good luck with your research in embroidery… I left you a message.”

3.5. The Overt-Latent Layers of Consciousness

“Here I think I looked behind to see knots that I think were really my biggest problem—the knots from behind. I wouldn’t have noticed, and it would have gotten completely complicated, and it was impossible to solve it because it’s a crazy knot. It’s like the thing in front, everything looks perfect and in order, but you don’t see the back, you don’t see what’s going on inside the person, and sometimes you don’t understand why it (the embroidery) isn’t finished. But (this is exactly the problem) there are ties behind, and you don’t see it. But over time I embroidered more slowly, I looked at the back more often, I just learned to look back and see that everything is fine from time to time.”

“You can really see and feel the parts where we got angry, and the parts where we were like “Oh man, no no” {imitating someone who is dissatisfied and making the group laugh W.N} […] On the one hand, you can see the beauty and the investment, and on the other hand, you can see the irritation and the frustration. It’s seeing what’s behind the scenes, let’s say that in an acrylic painting, it’s very hard to see because everything is in layers, and you can’t see the back.”

“This text talks about once I’ll be mentally stable then ‘watch out’ I’m going to be the best (Some day in the future). This statement is more with myself, most of the things I create are just me with myself, but here maybe because I’ve been becoming more stable recently, I see that I’m gaining self-confidence, and I’m more myself, so when I say such a statement in embroidery, I also direct it to the environment. “It’s all for you”, for society in general. it’s like ‘watch out’.”

“Embroidery is good as a gift because it is handmade.”Participant 8

“Because you can create a lot of things with it, and it’s very beautiful, and the fact that it’s handmade shows that someone made an effort and made something special for someone else.”Participant 10

“You can really see as if from the back too, you can see the process. In fact, […] You can see the effort. I think you can feel it. So that’s what makes it such a meaningful gift. On the one hand you can see the beauty and the investment, and on the other hand you can see the irritation (laughing) and the frustration.”Participant 11

“In an embroidery group there is more intimate conversation, maybe because the act of embroidery is repetitive, and you don’t have to think all the time, and maybe because we are just girls. Here I feel that it is possible to open up and say what wasn’t good today, who annoyed me and who didn’t, which instructor annoyed me, which kid annoyed me, or vice versa. […] In other groups, I won’t say things like that, unless I feel comfortable. Most of the times in the other groups they are more like straightforward, learning and all the classes there are, like, I’m also in social psychology, philosophy and photography and there it’s not like that, it’s not intimate. […] Here we also advise each other. And it happens a lot. Giving advice in personal life as well, someone says, let’s say something happened, and also regarding the works themselves, if I wondered whether to do one thing or another in the embroidery and the girls helped me and it was like I went with it.”

“In the dorms, I once shouted that I was in pain because of my period, and they told me it was not appropriate […] In the embroidery group I started embroidering because it (menstruation) hurt me, really hurt me. Other girls identified with it. I knew there was something beyond that. It’s not just me who suffers from my period and it’s not just me who will connect to that.

Through embroidery, I can convey that I am in pain and I have my period and I, it’s difficult and yes, it’s something more feminist and it’s okay to talk about it, about menstrual pain and menstruation in general also in such a way, through embroidery, that is delicate and feminine, precise and sketched and [made using] such delicate motor skills. It is also possible to be a feminist in this. It doesn’t have to be masculine and rude and blunt; it can be strong and blunt anyway.”

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Conclusions

6. Practical Implications for Research and Clinical Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collier, A.F. The Well-Being of Women Who Create With Textiles: Implications for Art Therapy. Art Ther. 2011, 28, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlock, L.R. Stories in the Cloth: Art Therapy and Narrative Textiles. Art Ther. 2016, 33, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wilckens, L. Embroidery; Oxford Art Online: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, C. The Modern Embroidery Movement; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, J.; Binkley, L. Introduction: Stitching the Self. In Stitching the Self: Identity and the Needle Arts; Amos, J., Binkley, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, C.E.; Brooks, M. Silent Needles, Speaking Flowers: The Language of Flowers as a Tool for Communication in Women’s Embroidery in Victorian Britain. In Proceedings of the 11th Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, Honolulu, HI, USA, 24–27 September 2008; Volume 93. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, J. “From Prison to Citizenship,” 1910: The Making and Display of a Suffragist Banner. In Stitching the Self: Identity and the Needle Arts; Amos, J., Binkley, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2020; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBrinn, J. “Knitting Is the Saving of Life; Adrian Has Taken It up Too”: Needlework, Gender, and the Bloomsbury Group. In Stitching the Self: Identity and the Needle Arts; Amos, J., Binkley, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2020; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlo, J.C. Suturing My Soul: In Pursuit of the Broderie de Bayeux. In Stitching the Self: Identity and the Needle Arts; Amos, J., Binkley, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2020; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanbek, A.; Malhotra, B.; Kaimal, G. Indigenous and Traditional Arts in Art Therapy: Value, Meaning, and Clinical Implications. Arts Psychother. 2022, 77, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, L. Preface. In Craft in Art Therapy: Diverse Approaches to the Transformative Power of Craft Materials and Methods; Leone, L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, E.S. Embroidering Pieces of Place. In Craft in Art Therapy: Diverse Approaches to the Transformative power of Craft Materials and Methods; Leone, L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, H. Embroidered Palestine: A Stitched Narrative. Narrat. Cult. 2016, 3, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmahmann, B. Stitches as Sutures: Trauma and Recovery in Works by Women in the Mapula Embroidery Project. Afr. Arts 2005, 38, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoshevski, M.; Huss, E. Using Crafts in Art Therapy Through an Intersectional Feminist Lens: The Case of Bedouin Embroidery in Israel. In Craft in Art Therapy: Diverse Approaches to the Transformative Power of Craft Materials and Methods; Leone, L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J. Threading the Needle: When Embroidery Was Used to Treat-Shock. J. R. Army Med. Corps 2018, 164, 390–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggin, M.D. Stitching (for) His Life: Morris William Larkin’s Prisoner of war Sampler. J. Mod. Craft 2013, 6, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggin, M.D. Threads of Feeling: Embroidering Craftivism to Protest the disappearances and Deaths in the “war on Drugs” in Mexico. In New Insights into Rhetoric and Argumentation; Runjic-Stoilova, A., Varošanec-Škaric, G., Eds.; Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences: Split, Croatia, 2017; pp. 311–336. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, C.; Lacroix, L.; Bagilishya, D.; Heusch, N. Working with Myths: Creative Expression Workshops for immigrant and Refugee Children in a School Setting. Art Ther. 2003, 20, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, A. A Proposal for Culturally Informed Art Therapy With Syrian Refugee Women: The Potential for Trauma Expression Through Embroidery (Une Proposition d’art-Thérapie Adaptée à La Culture de Femmes Réfugiées Syriennes: Le Potentiel de La Broderie Pour l’expression Du Traumatisme). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 2018, 31, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, M. Hanging on by a Thread: Confronting Mental Illness and Manifesting through Embroidery. Master’s Thesis, Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeman, J.R.; Samuelson, S.J.; McEvoy, K.N. Analysis of a Silent Voice: A Qualitative Inquiry of Embroidery by a Patient with Schizophrenia. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2013, 51, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, A. Well-Being 2016 Co-Creating Pathways to Well-Being: Book of Proceeding: The Third Conference Exploring the Multi-Dimensions of Well-Being; Coles, R., Costa, S., Watson, S., Eds.; Birmingham City University: Birmingham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwein, B.H. Emotions: Some Historical Observations. Hist. Psychol. 2021, 24, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B. “Regular Progressive Work Occupies My Mind Best”: Needlework as a source of Entertainment, Consolation and Reflection. Text. J. Cloth Cult. 2016, 14, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.J. Embroidery, Resilience, and Discovery. In Healing Through the Arts for Non-Clinical Practitioners; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalo, P. Embroidery as Narrative: Black South African Women’s Experiences of Suffering and Healing. Agenda 2014, 28, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, R. Story Cloths as a Counter-archive: The Mogalakwena Craft Art Development Foundation Embroidery Project. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pretoria, Hatfield, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Or, E. Shimur Omanut Yotsey Etyopya [Ethiopian Art Conservation]. Etrog J. Educ. 2012, 54, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Huss, E.; Cwikel, J. Researching Creations: Applying Arts-Based Research to Bedouin Women’s Drawings Ephrat Huss and Julie Cwikel. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2005, 4, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.S. Masculine and Feminine: The Natural Flow of Opposites in the Psyche; Shambhala Publications: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kast, V.; Whitcombe, B. Anima/Animus. In The Handbook of Jungian psychology; Papadopoulo, R.K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzer, R. Al Hatarucah Rikmat Em of Ita Gartner [About the Exhibition’s Embroidery—Ita Gartner]. 2007. Available online: https://www.ruthnetzer.com/image/usrs/182625/ftp/my_files/att2/%D7%94%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%A7%D7%9E%D7%94%20%D7%A9%D7%9C%20%D7%90%D7%9E%D7%90.doc?id=8413773 (accessed on 1 May 2023). (In Hebrew).

- Netzer, R. Tseva Adom Yalda Shel Adva Drori [About the Exhibition “Red Color Girl!” of Adva Drori]. Bein Hamilim 2013. Available online: www.smkb.ac.il/us/college-publications/beyn-hamilim/volume8/red-color-girl/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Farber, L. Skin Aesthetics. Theory Cult. Soc. 2006, 23, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleci, R. Cut in the Body: From Clitoridectomy to Body Art. In Thinking Thorogh the Skin; Ahmed, S., Stacey, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, A.F.; von Károlyi, C. Rejuvenation in the “making”: Lingering Mood Repair in Textile Handcrafters. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2014, 8, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilton, G. Art Therapy and Flow: A Review of the Literature And. Art Ther. 2013, 30, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myzelev, A. Whip Your Hobby into Shape: Knitting, Feminism and Construction of Gender. Textile 2009, 7, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, B. Applying Principles of Neurodevelopment to Clinical Work with Maltreated and Traumatized Children: The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. In Working with Traumatized Youth in Child Welfare; Webb, N.B., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cape, E. Fibre Crafting as a Creative Intervention for Adolescent Low Self-Esteem; Counselling Psychology Research Project; Division of Arts and Sciences City University of Seattle: Seattle, WA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, S. Art Therapists’ Work with Textiles. Unpublished Thesis, Faculty of the Department of Marital and Family Therapy, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.H. Self-Identity and Self-Esteem during Different Stages of Adolescence: The Function of Identity Importance and Identity Firmness. Chin. J. Guid. Couns. 2019, 55, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the Life Cycle; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M. Role of Adolescent Development in the Transition Process. Prog. Transplant. 2006, 16, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, J.H.; Berkman, E.T. The Development of Self and Identity in Adolescence: Neural Evidence and Implications for a Value-Based Choice Perspective on Motivated Behavior. Child Dev. Perspect. 2018, 12, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisk, L.M.; Gee, D.G. Stress and Adolescence: Vulnerability and Opportunity during a Sensitive Window of Development. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascheroni, G.; Vincent, J.; Jimenez, E. “Girls Are Addicted to Likes so They Post Semi-Naked Selfies’’: Peer Mediation, Normativity and the Construction of Identity Online. Cyberpsychology 2015, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, L.H. Depression in Girls during the Transition to Adolescence: Risks and Effective Treatment. J. Child Adolesc. Couns. 2018, 4, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, D.A.; Vossen, H.G.M.; van der Kolk-van der Boom, P. Social Media and Body Dissatisfaction: Investigating the Attenuating Role of Positive Parent-Adolescent Relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stänicke, L.I.; Haavind, H.; Rø, F.G.; Gullestad, S.E. Discovering One’s Own Way: Adolescent Girls’ Different Pathways into and out of Self-Harm. J. Adolesc. Res. 2020, 35, 605–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, C.M.; Caporino, N.E.; Kendall, P.C. Comorbidity of Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents: 20 Years After. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 816–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, N.; MacQueen, G. Adolescence as a Unique Developmental Period. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, 40, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Elvidge, H. Adolescent Mental Health in Crisis. BMJ 2018, 361, k2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guessoum, S.B.; Lachal, J.; Radjack, R.; Carretier, E.; Minassian, S.; Benoit, L.; Moro, M.R. Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Lockdown. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, M.T.; Szenczy, A.K.; Klein, D.N.; Hajcak, G.; Nelson, B.D. Increases in Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 3222–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, M.; Shenaar-Golan, V.; Yatzker, U. Children and Adolescents’ Mental Health Following COVID-19: The Possible Role of Difficulty in Emotional Regulation. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 865435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, R.G.; Hall, J.A.; Christofferson, J.L. Conceptualizing Digital Stress in Adolescents and Young Adults: Toward the Development of an Empirically Based Model. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.B. Adolescent Girls in Crisis: Intervention and Hope; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N. Gender Differences in Associations between Digital Media Use and Psychological Well-Being: Evidence from Three Large Datasets. J. Adolesc. 2020, 79, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, J.; Skogens, L.; Schön, U.K. Young People’s Recovery Processes from Mental Health Problems—A Scoping Review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, C.A.; Hiance-Steelesmith, D.L.; Bridge, J.A.; Lester, N.; Sweeney, H.A.; Hurst, M.; Campo, J.V. Factors Associated with Timely Follow-up Care after Psychiatric Hospitalization for Youths with Mood Disorders. Psychiatr. Serv. 2016, 67, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D.; Harris, M. Adolescence: Talks and Papers by Donald Meltzer and Martha Harris. In Adolescence; Williams, M.H., Ed.; The Harris Meltzer Trust: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitch, M. Yeladim Venoar Eam Hafraot Nafshiot: Zchuiot Vesherutim Bemaarechet Habriut. Harevach Vehahinuch [Children and Adolescents with Mental Disorders]. In Rights and Services in the Health, Welfare, and Education Systems. The Research and the Information Center of Knesset; 2013. Available online: https://www.knesset.gov.il/committees/heb/material/data/yeled2015-07-13.doc (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Breuner, C.C.; Alderman, E.M.; Jewell, J.A.; Committee on Adolescence; Committee on Hospital Care. The Hospitalized Adolescent. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022060646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialkowski, A.; Shaffer, K.; Ball-Burack, M.; Brooks, T.L.; Trinh, N.H.T.; Potter, J.E.; Peeler, K.R. Trauma-Informed Care for Hospitalized Adolescents. Curr. Pediatr. Rep. 2022, 10, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, T. Adolescents’ Perspectives about Brief Psychiatric Hospitalization: What Is Helpful and What Is Not? Psychiatr. Q. 2011, 82, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetzel, K.B.; Scherer, D.G. Therapeutic Engagement with Adolescents in Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 2003, 40, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbett, S. Reaching the Hard to Reach: Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation of School-Based Arts Therapies with Young People with Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2016, 21, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uttley, L.; Scope, A.; Stevenson, M.; Rawdin, A.; Buck, E.T.; Sutton, A.; Stevens, J.; Kaltenthaler, E.; Dent-Brown, K.; Wood, C. Systematic Review and Economic Modelling of the Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Art Therapy among People with Non-Psychotic Mental Health Disorders. Health Technol. Assess. 2015, 19, 1–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slayton, S.C.; D’Archer, J.; Kaplan, F. Outcome Studies on the Efficacy of Art Therapy: A Review of Findings. Art Ther. 2010, 27, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, C. Effects of Art Therapy on Identity and Self-Esteem in Youths in the Foster Care System. Master’s Dissertation, Department of Art Therapy in the Graduate Program, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College, St Mary-Of-The-Woods, IN, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Naor-Inbar, N. Draw Your Story: The Main Themes That Arise from the Art of Adolescent Girls at Risk in an Open Studio in a Boarding School. Unpublished Thesis Master’s Dissertation, Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences, School of Arts Therapy. University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, F.; Isobel, S.; Starling, J. Evaluating the Use of Responsive Art Therapy in an Inpatient Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services Unit. Australas. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elul, H. Yetsugim Shel Bait, Em Veyeled Betipul Beomanut Bemisgeret Pnimia [Re presentations of Home, Mother and Child in Art Therapy within a Boarding School]. Bein Hamilim [Among the Words] 2010, 2. Available online: www.smkb.ac.il/us/college-publications/beyn-hamilim/volume2/hadas-elul/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kelemen, L.J.; Shamri-Zeevi, L. Art Therapy Open Studio and Teen Identity Development: Helping Adolescents Recover from Mental Health Conditions. Children 2022, 9, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuaf, H.; Orkibi, H. Community-Based Rehabilitation Programme for Adolescents with Mental Health Conditions in Israel: A Qualitative Study Protocol. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e032809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, D.; Harris, T.; Laing, S. Open Studio Process as a Model of Social Action: A Program for at-Risk Youth. Art Ther. 2005, 22, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, D.; Bat-Or, M. The Open Studio Approach to Art Therapy: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 568042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Ghazinour, M.; Hammarström, A. Different Uses of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory in Public Mental Health Research: What Is Their Value for Guiding Public Mental Health Policy and Practice? Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Baranowski, K.; Abdel-Salam, L.; McGinley, M. Youth Participatory Action Research: Agency and Unsilence as Anti-Classist Practice. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2018, 4, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P. Targets and Outcomes of Psychotherapies for Mental Disorders: An Overview. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M. On Research, Art, and Transformation: Multigenerational Participatory Research, Critical Positive Youth Development, and Structural Change. Qual. Psychol. 2016, 3, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindquist-Grantz, R.; Abraczinskas, M. Using Youth Participatory Action Research as a Health Intervention in Community Settings. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory Action Research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Designs and Data Collection. In Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P.; Fusch, G.E.; Ness, L.R. Denzin’s Paradigm Shift: Revisiting Triangulation in Qualitative Research. J. Soc. Change 2018, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. The Significance of Saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Naturalistic Inquiry and the Saturation Concept: A Research Note. Qual. Res. 2008, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufford, L.; Newman, P. Bracketing in Qualitative Research. Qual. Soc. Work 2012, 11, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillian, R. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin, M.; Drew, S. Questions of Process in Participant-Generated Visual Methodologies. Vis. Stud. 2010, 25, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M.; Cox, S. Audience Engagement and Impact: Ethical Considerations in Art-Based Health Research. J. Appl. Arts Health 2017, 8, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, G.; Hahn, M.; Recchia, H.; Wainryb, C. Rethinking Responses to Youth Rebellion: Recent Growth and Development of Restorative Practices in Schools. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 35, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. Making Restorative Sense with Deleuzian Morality, Art Brut and the Schizophrenic. Deleuze Stud. 2010, 4, 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keulemans, G. The Geo-Cultural Conditions of Kintsugi. J. Mod. Craft 2016, 9, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardi-Zonna, K. Finding Buddha in the Clay Studio: Lessons for Art Therapy. Art Ther. 2020, 37, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, N.; Barak, A.; Yaniv, D. Different Shades of Beauty: Adolescents’ Perspectives on Drawing From Observation. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, J.F.; Roll, S.J. Women, Poverty, and Trauma: An Empowerment Practice Approach. Soc. Work 2015, 60, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, S.K. Autistic Community and the Neurodiversity Movement: Stories from the Frontline; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2020; p. 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G.; Cann, A. Evaluating Resource Gain: Understanding and Misunderstanding Posttraumatic Growth. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 56, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bion, W.R. Two Papers: “The Grid” and “Caesura”, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9780946439775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieber, S. “Je Me Declare Dieu-Mère, Femme Créateur”: Johanna Wintsch’s Needlework at the Swiss Psychiatric Asylums Burghölzli and Rheinau, 1922–1925. In Stitching the Self: Identity and the Needle Arts; Amos, J., Binkley, L., Eds.; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2020; pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, S. The Eye of the Needle: Craftivism as an Emerging Mode of Civic Engagement and Cultural Participation. Doctoral Dissertation, Teachers College, New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nordenstam, A.; Wictorin, M.W. Comics Craftivism: Embroidery in Contemporary Swedish Feminist Comics. J. Graph. Nov. Comics 2022, 13, 174–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Bioecological Circle | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Control versus release/freedom | Micro | Most of the Participants |

| Meso | Most of the Participants | |

| Macro | Most of the Participants | |

| Calmness | Micro | Most of the Participants |

| Meso | Half of the Participants | |

| Macro | Half of the Participants | |

| Exceptional vs. conventional | Micro | Most of the Participants |

| Meso | Most of the Participants | |

| Macro | Half of the Participants | |

| Stitch through time | Micro | Most of the Participants |

| Meso | Half of the Participants | |

| Macro | Half of the Participants | |

| Overt-latent | Micro | Half of the Participants |

| Meso | Half of the Participants | |

| Macro | Few of the Participants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolk, N.; Bat Or, M. The Therapeutic Aspects of Embroidery in Art Therapy from the Perspective of Adolescent Girls in a Post-Hospitalization Boarding School. Children 2023, 10, 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061084

Wolk N, Bat Or M. The Therapeutic Aspects of Embroidery in Art Therapy from the Perspective of Adolescent Girls in a Post-Hospitalization Boarding School. Children. 2023; 10(6):1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061084

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolk, Nurit, and Michal Bat Or. 2023. "The Therapeutic Aspects of Embroidery in Art Therapy from the Perspective of Adolescent Girls in a Post-Hospitalization Boarding School" Children 10, no. 6: 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061084

APA StyleWolk, N., & Bat Or, M. (2023). The Therapeutic Aspects of Embroidery in Art Therapy from the Perspective of Adolescent Girls in a Post-Hospitalization Boarding School. Children, 10(6), 1084. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061084