School and Bicultural Factors as Mediators between Immigrant Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and Adolescents’ Depression in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background: Family Stress Model and Family Systems Theory

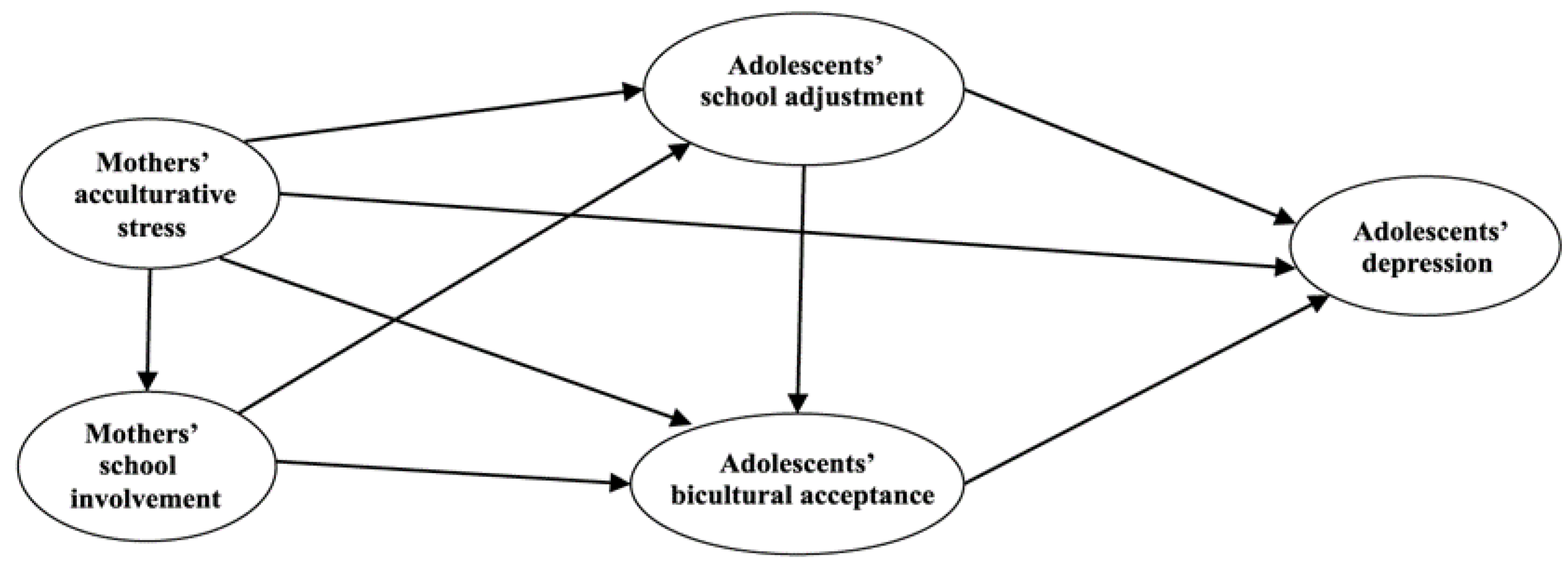

1.2. Direct and Indirect Pathways from Mothers’ Acculturative Stress to Adolescents’ Depression: Mediating Roles of Mothers’ School Involvement, Adolescents’ School Adjustment, and Adolescents’ Bicultural Acceptance

1.3. Differences in Structural Relationships According to the Sex of Adolescents

1.4. The Hypotheses and Research Question of this Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depression

2.2.2. Acculturative Stress

2.2.3. School Involvement

2.2.4. School Adjustment

2.2.5. Bicultural Acceptance

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

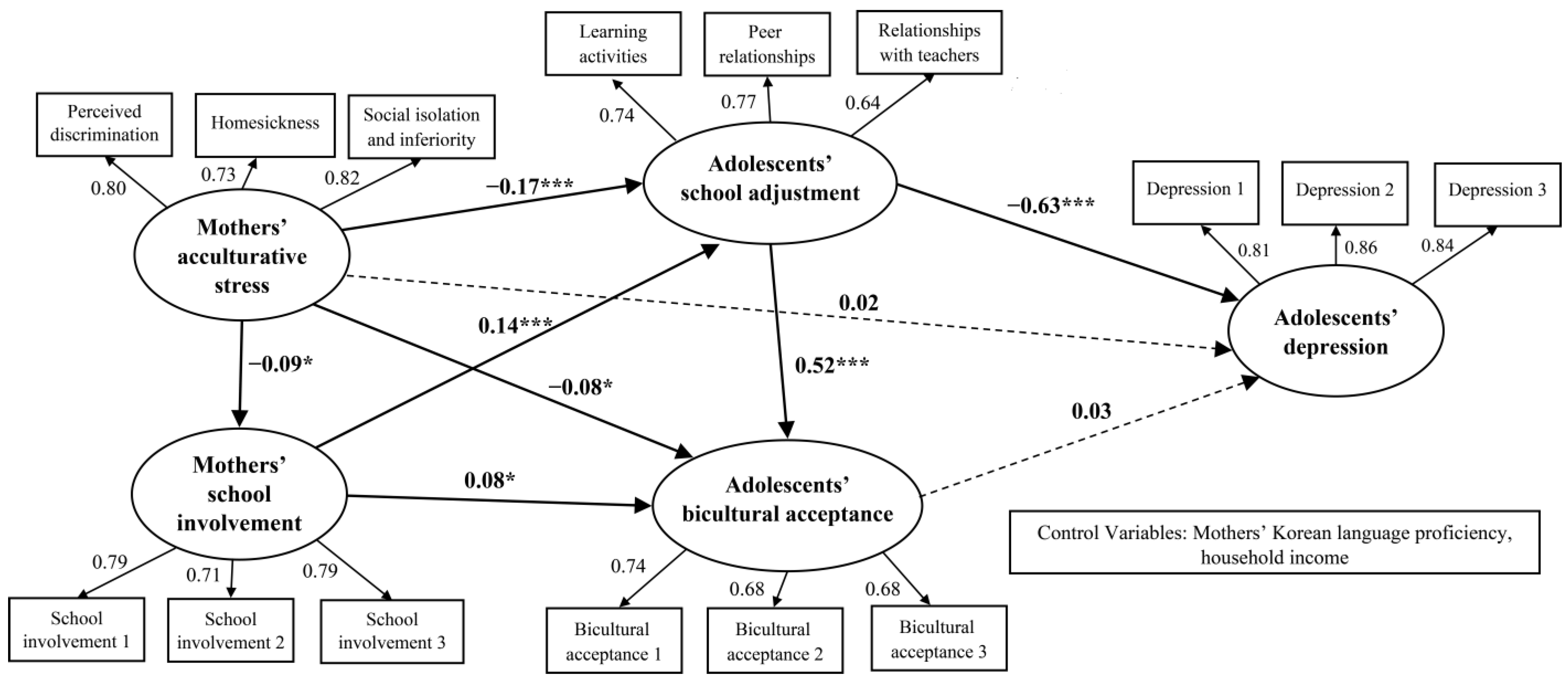

3.2. Direct and Indirect Relationships between Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and Adolescents’ Depression: Mediating Roles of Mothers’ School Involvement, Adolescents’ School Adjustment, and Adolescents’ Bicultural Acceptance

3.3. Differences in the Structural Relationships among Mothers’ Acculturative Stress, Mothers’ School Involvement, Adolescents’ School Adjustment, Adolescents’ Bicultural Acceptance, and Adolescents’ Depression according to the Sex of Adolescents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, H. Marriage Migration to South Korea: Issues, Problems, and Responses. Korea J. Popul. Stud. 2005, 28, 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Definition of Multicultural Family. Available online: http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0068878 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Kim, B. Current Status of Marriage Immigrants in Korea and Policy Tasks. Available online: http://www.nationsworld.kr/bbs/board.php?bo_table=academy&wr_id=55708&sst=wr_hit&sod=desc&sop=and&page=1 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Cho, H. Multiculturalism and Female Marriage Immigrants in Korea. J. Eurasian Stud. 2010, 7, 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Women’s Development Institute. Marriage Immigrants by Nationality in 2021. Available online: https://gsis.kwdi.re.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=338&tblId=DT_5CA0510N (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Korean Educational Statistics. Number of Multicultural Students. Available online: https://kess.kedi.re.kr/eng/index (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- Bao, J.; Greder, K. Economic Pressure and Parent Acculturative Stress: Effects on Rural Midwestern Low-Income Latinx Child Behaviors. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2023, 44, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Wang, Y. Parental Acculturative Stressors and Adolescent Adjustment through Interparental and Parent-Child Relationships in Chinese American Families. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y. Effect of Married Immigrant Women’s Acculturative Stress on School Adjustment in Adolescent Children: Mediating Roles of School Involvement and Parenting Efficacy. Korean J. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 28, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y. Relationship between Marriage Immigrant Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and their Adolescent Children’s Career Decidedness in South Korea: Mediating Roles of Parenting and School Adjustment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-H.; Lee, S.D. Exploring the Predictors of School Adjustment and Academic Achievement during Elementary to Middle-School Transition for Adolescents in Multicultural Families. Korean Educ. Inq. 2017, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S. Factors Affecting School Adjustment of Middle School Freshmen. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2008, 15, 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Youth Counseling & Welfare Institute. A Year after COVID-19, a Record of Changes in Adolescent Mental Health. Available online: https://www.kyci.or.kr/fileup/issuepaper/IssuePaper_202105.pdf (accessed on 29 December 2022).

- Kang, S. Adolescent Depression and Anxiety are Getting Worse… How to Regain “Healthy Mentality”? Chosun Media. 2022. Available online: https://health.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2022/08/12/2022081201904.html (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Kim, J.; Kong, B.; Kang, J.; Moon, J.; Jeon, D.; Kang, E.; Ju, H.; Lee, Y.; Jung, D. Comparative Study of Adolescents’ Mental Health between Multicultural Family and Monocultural Family in Korea. J. Korean Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 26, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner, M.K.; Van de Vijver, F.J.R.; Noack, P. Acculturation and School Adjustment of Early-Adolescent Immigrant Boys and Girls in Germany: Conditions in School, Family, and Ethnic Group. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 352–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. Mediated Effects of Acculturative Stress and Maternal Parenting Stress on Internalized Problems of Children in Multicultural Families: Focused on the Mediating Role of Mothers’ Depression. J. Sch. Soc. Work 2014, 27, 353–376. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Unger, J.B.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Szapocznik, J. Rethinking the Concept of Acculturation: Implications for Theory and Research. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lee, M. The Effects of Adolescents’ School Adjustment on Depression in their Transitional Period. J. Fam. Better Life 2014, 32, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- So, S.; Song, M.; Kim, C. The Effects of Perceived Parenting Behavior and School Adjustment on the Depression of Early Adolescent. Korean J. Youth Stud. 2010, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J.Y. A Study of School Adaptation among Children of Multicultural Families in the Subtypes of Bicultural Acceptance Attitudes. Korean J. Soc. Welf. Res. 2020, 65, 165–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nho, C.R.; Hong, J.J. Adaptation of Migrant Workers’ Children to Korean Society: About Adaptation of Mongolian Migrant Worker’s Children in Seoul, Gyeong gi Area. J. Korean Soc. Child Welf. 2006, 22, 127–160. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Yang, M.; Park, Y. Exploring the Longitudinal Changes of Multicultural Adolescents’ Achievement Motivation by the Developmental Patterns of their Bicultural Acceptance. J. Educ. Cult. 2020, 26, 663–689. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, L.; Choi, N.; Kang, S. Minority Language Proficiency of Multicultural Adolescents: The Effects of Bicultural Acceptance Attitudes, Parents’ Educational Support, and the Use of the Minority Language at Home. Fam. Environ. Res. 2021, 59, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-H.; Yun, J.-M.; Han, J.-Y. Verification of the Longitudinal Relationship between Mothers’ Cultural Adaptation Patterns, Multicultural Acceptability of Multicultural Adolescents, and National Identity: Focusing on the Mediating Effect of the Autoregressive Cross-Lagged Model. J. Digit. Converg. 2021, 19, 453–467. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.-Y.; Paik, J. The Effect of Bicultural Acceptance Attitude on Depression of Multicultural Adolescent: Mediating Effect of Social Withdrawal. J. Ind. Converg. 2022, 20, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Conger, R.D.; Elder, G.H.J. Families in Troubled Times: Adapting to Change in Rural America; Aldine: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Meca, A.; Unger, J.B.; Romero, A.; Gonzales-Backen, M.; Piña-Watson, B.; Cano, M.Á.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Des Rosiers, S.E.; Soto, D.W.; et al. Latino Parent Acculturation Stress: Longitudinal Effects on Family Functioning and Youth Emotional and Behavioral Health. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Spillover-Crossover Model. In New Frontiers in Work and Family Research; Grzywacz, J.G., Demerouti, E., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Salo, V.C.; Schunck, S.J.; Humphreys, K.L. Depressive Symptoms in Parents are Associated with Reduced Empathy toward Their Young Children. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Koo, Y.; Lee, K. The Effect of Parental School Involvement on Children’s School Adjustment: The Mediating Role of Parental Efficacy. Korean J. Hum. Dev. 2016, 23, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover-Dempsey, K.V.; Sandler, H.M. Parental Involvement in Children’s Education: Why does It Make a Difference? Teach. Coll. Rec. 1995, 97, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.E.; Taylor, L.C. Parental School Involvement and Children’s Academic Achievement: Pragmatics and Issues. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 13, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S. The Effects of Multicultural Families Parents Participation in School Activities to Children’s School Adaptation. Multicult. Diaspora Stud. 2019, 14, 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, H.; Mo, K.-H.; Seong, S.-H. A Study on How the School Activity Participation of Parents with Migrant Background can Affect their Parenting Efficacy. J. Educ. Cult. 2020, 26, 1239–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, B.; Kim, K.-K. Determinants of International Marriage Migrant Women’s Participation in School Activities at the Elementary School Level. Korean J. Sociol. Educ. 2012, 22, 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.S. Parents’ Involvement and Adolescents’ School Adjustment: Teacher-Student Relationships as a Mechanism of Change. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 34, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutland, A.; Cameron, L.; Jugert, P.; Nigbur, D.; Brown, R.; Watters, C.; Hossain, R.; Landau, A.; Le Touze, D. Group Identity and Peer Relations: A Longitudinal Study of Group Identity, Perceived Peer Acceptance, and Friendships amongst Ethnic Minority English Children. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 30, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikhonov, A.A.; Espinosa, A.; Huynh, Q.L.; Anglin, D.M. Bicultural Identity Harmony and American Identity are Associated with Positive Mental Health in U.S. Racial and Ethnic Minority Immigrants. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birman, D.; Weinstein, T.; Chan, W.; Beehler, S. Immigrant Youth in US Schools: Opportunities for Prevention. Prev. Res. 2007, 14, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Cho, S.-S.; Lee, S.-Y. The Relationship between Parental Monitoring and Support and Multicultural Acceptability Attitude among Multiethnic Adolescents: Focusing on the Self-Esteem. Multicult. Educ. Stud. 2022, 15, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silinskas, G.; Kiuru, N.; Aunola, K.; Metsäpelto, R.-L.; Lerkkanen, M.-K.; Nurmi, J.-E. Maternal Affection Moderates the Associations between Parenting Stress and Early Adolescents’ Externalizing and Internalizing Behavior. J. Early Adolesc. 2020, 40, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xue, Y.; Cheng, C.; Park, Y. Relationships among Immigrant Women’s Perceived Social Support, Acculturation Stress, and their Children’s School Adjustment. Korean J Educ. Methodol. Stud. 2017, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang-Schweig, M.; Miller, B.A. Examining the Interdependence of Parent-Adolescent Acculturation Gaps on Acculturation-Based Conflict: Using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, D.B.; Andrews, K. Processes of Adolescent Socialization by Parents and Peers. Int. J. Addict. 1987, 22, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radke-Yarrow, M.; Kochanska, G. Anger in Young Children. In Psychological and Biological Approaches to Emotion; Stein, N.L., Leventhal, B., Trabasso, T., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Güngör, D.; Bornstein, M.H. Gender and Developmental Pathways of Acculturation and Adaptation in Immigrant Adolescents. In Gender Roles in Immigrant Families; Chuang, S.S., Tamis-LeMonda, C.S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski, J.M.; Frank, E.; Young, E.; Shear, M.K. Adolescent Onset of the Gender Difference in Lifetime Rates of Major Depression: A Theoretical Model. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, J.P.; O’Connell, M. Gender Differences in Vulnerability to Maternal Depression during Early Adolescence: Girls Appear More Susceptible than Boys. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.P.; Kingree, J.B.; Desai, S. Gender Differences in Long-Term Health Consequences of Physical Abuse of Children: Data from a Nationally Representative Survey. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizeta, F.A.; Loureiro, S.R.; Pasian, S.R. Maternal Depression, Social Vulnerability and Gender: Prediction of Emotional Problems among Schoolchildren. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turjeman, H.; Mesch, G.; Fishman, G. The Effect of Acculturation on Depressive Moods: Immigrant Boys and Girls during their Transition from Late Adolescence to Early Adulthood. Int. J. Psychol. 2008, 43, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NYPI Youth and Children Data Archive. Multicultural Adolescents Panel Study. Available online: https://www.nypi.re.kr/archive/mps/program/examinDataCode/view?menuId=MENU00226&pageNum=1&titleId=146&schType=0&schText=&firstCategory=&secondCategory= (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Lee, K.; Baek, H.-J.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. The Annual Report of Korean Children and Youth Panel Survey 2010 (Research Report 11-R10); National Youth Policy Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010; pp. 1–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kim, J.; Won, H. Korean Manual of Symptom Checklist-90-Reversion; Juksung Publishers: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1984; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bandalos, D.L.; Finney, S.J. Item Parceling Issues in Structural Equation Modeling. In New Developments and Techniques in Structural Equation Modeling; Marcoulides, G.A., Schumacker, R.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 269–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu, D.S.; Asrabadi, B.R. Development of an Acculturative Stress Scale for International Students: Preliminary Findings. Psychol. Rep. 1994, 75, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R. A Study on Acculturative Stress among North Korean Defectors. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.K.; Baek, H.-J.; Lim, H.-J.; Lee, K.-O. Korea Children and Youth Panel Survey 2010 (Research Report 10-R01); National Youth Policy Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010; pp. 1–254. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.P. Concepts and Knowledge of Structural Equation Modeling; Hanarae Academy: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, B.R. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos 19: Principles and Practice; Chungram: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practices of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-H. Effect of Family Income on Academic Achievement, Depression Anxiety, and Aggression Focusing on Panel Comparison of Children and Adolescents. J. Sch. Soc. Work 2019, 45, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. The Effect of Parents’ Korean Proficiency on their Children’s Psychological Health within Multicultural Families: Focusing on the Mediated Effect of the Communication Level between Parents and their Children. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural Equation Models with Nonnormal Variables: Problems and Remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement Invariance Conventions and Reporting: The State of the Art and Future Directions for Psychological Research. Dev. Rev. 2016, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology. The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-Y.; Park, S.-K.; Kim, M.-S. Effects of Bicultural Characteristics and Social Capital on Psychological Adaptation. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2013, 13, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.M.; Rhee, C.-W. Community Participation Affects Marriage Immigrant Women’s Parenting Efficacy. Korean J. Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 55, 237–263. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, M.-W.; Ha, M.-J. A Study on Teachers’ Two-Fold Recognition of Students from Multicultural Family. Multicult. Educ. Stud. 2016, 9, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. Translation Service for Parents of Multicultural Families, Fully Expanded in Elementary, Middle and High Schools. Jejukyeongje Ilbo. 2023. Available online: http://www.jejukyeongje.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=30416 (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Gonida, E.N.; Cortina, K.S. Parental Involvement in Homework: Relations with Parent and Student Achievement-Related Motivational Beliefs and Achievement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, K.A. A Validation of the Family Involvement Questionnaire-High School Version. Ph.D. Thesis, Minnesota State University, Mankato, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J.; Ha, J.H.; Jue, J. Influences of the Differences Between Mothers’ and Children’s Perceptions of Parenting Styles. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 552585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Awareness of Gender Equality has Improved, But… The Problem of “Women-Centered Parenting” Still Persists. The Segye Times. 2022. Available online: http://www.segye.com/newsView/20220419510145?OutUrl=naver (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Oh, S.-H. The Study on the Eco-Systemic Variables Affecting Multicultural Family Adolescents’ Depression. J. Community Welf. 2016, 56, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogoro, M.; Minescu, A.; Moriarty, M. Cultural Identity in Bicultural Young Adults in Ireland: A Social Representation Theory Approach. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsakhurdia, V. Adaptation in a Dialogical Perspective—From Acculturation to Proculturation. Cult. Psychol. 2018, 24, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudmin, F. Constructs, Measurements and Models of Acculturation and Acculturative Stress. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.; Ram, A. Theorizing Identity in Transnational and Diaspora Cultures: A Critical Approach to Acculturation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Background Characteristics | Categories | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Age | Under 30 years old | 16 (1.2) |

| Between 30 and 39 years | 250 (20.2) | ||

| Between 40 and 49 years | 822 (66.4) | ||

| Between 50 and 59 years | 148 (12.0) | ||

| Above 60 years old | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Country of origin | Japan | 458 (36.9) | |

| Philippines | 313 (25.3) | ||

| Ethnic Koreans of China | 236 (19.1) | ||

| China | 85 (6.9) | ||

| Thailand | 47 (3.8) | ||

| Others (Vietnam, etc.) | 99 (8.0) | ||

| Final educational attainment | Middle school graduation or lower | 136 (11.0) | |

| High school graduation | 579 (46.8) | ||

| Second- or third-year college graduation or higher | 523 (42.2) | ||

| Korean language proficiency | High level | 830 (67.1) | |

| Medium level | 315 (25.4) | ||

| Low level | 93 (7.5) | ||

| Adolescents | Korean language proficiency | High level | 1207 (97.5) |

| Medium level | 19 (1.5) | ||

| Low level | 12 (1.0) | ||

| Proficiency in foreign mothers’ | High level | 210 (17.0) | |

| native language | Medium level | 149 (12.0) | |

| Low level | 879 (71.0) | ||

| Household income (KRW) | Under 2 million | 349 (28.2) | |

| Between 2 and 3.99 million | 754 (60.9) | ||

| Between 4 and 5.99 million | 122 (9.9) | ||

| Above 6 million | 13 (1.0) | ||

| Variables | 1-1. | 1-2. | 1-3. | 2. | 3-1. | 3-2. | 3-3. | 4. | 5. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1. DISC | |||||||||

| 1-2. HOM | 0.59 ** | ||||||||

| 1-3. SII | 0.66 ** | 0.59 ** | |||||||

| 2. SCHINV | −0.02 | −0.10 ** | −0.10 ** | ||||||

| 3-1. SLE | −0.07 * | −0.15 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.14 ** | |||||

| 3-2. SPE | −0.10 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.56 ** | ||||

| 3-3. STE | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.08 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.50 ** | |||

| 4. BICA | −0.07 * | −0.12 ** | −0.10 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.32 ** | ||

| 5. DEP | 0.07 * | 0.10 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.02 | −0.45 ** | −0.45 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.27 ** | |

| M | 2.63 | 2.37 | 2.32 | 1.43 | 2.88 | 3.18 | 3.11 | 2.93 | 1.64 |

| SD | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.57 | 0.39 | 0.54 |

| Skewness | 0.12 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 1.09 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.25 | 0.06 | 0.53 |

| Kurtosis | −0.56 | −0.27 | −0.37 | 0.85 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.34 | 0.76 | −0.41 |

| Paths | b | β | S.E. | C.R. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Mothers’ school involvement | −0.05 | −0.09 * | 0.02 | −2.58 |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ school adjustment | −0.09 | −0.17 *** | 0.02 | −4.82 |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ depression | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.78 |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance | −0.03 | −0.08 * | 0.01 | −2.41 |

| Mothers’ school involvement → Adolescents’ school adjustment | 0.15 | 0.14 *** | 0.04 | 3.97 |

| Mothers’ school involvement → Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance | 0.06 | 0.08 * | 0.03 | 2.21 |

| Adolescents’ school adjustment → Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance | 0.40 | 0.52 *** | 0.03 | 12.20 |

| Adolescents’ school adjustment → Adolescents’ depression | −0.84 | −0.63 *** | 0.06 | −13.67 |

| Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance → Adolescents’ depression | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.62 |

| Indirect Pathways | b |

|---|---|

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Mothers’ school involvement → Adolescents’ school adjustment → Adolescents’ depression | 0.01 * |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ school adjustment → Adolescents’ depression | 0.07 ** |

| Models | χ2 (df) | Δχ2 (Δdf) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 436.692 (214) | - | 0.969 | 0.961 | 0.029 |

| Full metric invariance model | 458.673 (224) | 21.981 (10) * | 0.967 | 0.960 | 0.029 |

| Partial metric invariance model | 443.594 (220) | 6.902 (6) | 0.969 | 0.962 | 0.029 |

| Structural invariance model | 462.191 (229) | 18.597 (9) * | 0.968 | 0.962 | 0.029 |

| Paths | Boys (n = 605) | Girls (n = 633) | χ2 (df) | Δχ2 (Δdf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (β) | b (β) | |||

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Mothers’ school involvement | −0.04 (−0.08) | −0.04 (−0.09) * | 443.595 (221) | 0.001 (1) |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ school adjustment | −0.08 (−0.15) ** | −0.10 (−0.19) *** | 443.740 (221) | 0.146 (1) |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ depression | −0.02 (−0.03) | 0.04 (0.05) | 445.119 (221) | 1.525 (1) |

| Mothers’ acculturative stress → Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance | −0.04 (−0.09) * | −0.05 (−0.10) * | 443.809 (221) | 0.215 (1) |

| Mothers’ school involvement → Adolescents’ school adjustment | 0.14 (0.14) ** | 0.15 (0.14) ** | 443.596 (221) | 0.002 (1) |

| Mothers’ school involvement → Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.09 (0.12) * | 445.431 (221) | 1.837 (1) |

| Adolescents’ school adjustment → Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance | 0.44 (0.53) *** | 0.37 (0.51) *** | 444.320 (221) | 0.726 (1) |

| Adolescents’ school adjustment → Adolescents’ depression | −0.66 (−0.52) *** | −0.99 (−0.71) *** | 454.687 (221) | 11.093 (1) ** |

| Adolescents’ bicultural acceptance → Adolescents’ depression | −0.18 (−0.12) * | 0.04 (0.05) | 452.448 (221) | 8.854 (1) ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, Y. School and Bicultural Factors as Mediators between Immigrant Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and Adolescents’ Depression in Korea. Children 2023, 10, 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061010

Lim Y. School and Bicultural Factors as Mediators between Immigrant Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and Adolescents’ Depression in Korea. Children. 2023; 10(6):1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Yangmi. 2023. "School and Bicultural Factors as Mediators between Immigrant Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and Adolescents’ Depression in Korea" Children 10, no. 6: 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061010

APA StyleLim, Y. (2023). School and Bicultural Factors as Mediators between Immigrant Mothers’ Acculturative Stress and Adolescents’ Depression in Korea. Children, 10(6), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061010