Rehabilitation in Patients Diagnosed with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion of Studies

- People diagnosed with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (AMC) of every age;

- Rehabilitation interventions or studies that reports results related to rehabilitation approaches;

- Any type of comparator (e.g., early treatment versus late treatment, multidisciplinary approach versus single approach, physiotherapy versus other treatments);

- Health status, joint contractures, joint deformities or independence in activities of daily living;

- Any type of study, in any language.

- Any associated neuromuscular disease;

- Any design of study that do not report results from included participants (e.g., protocol of study);

- Interventions focused only on surgery.

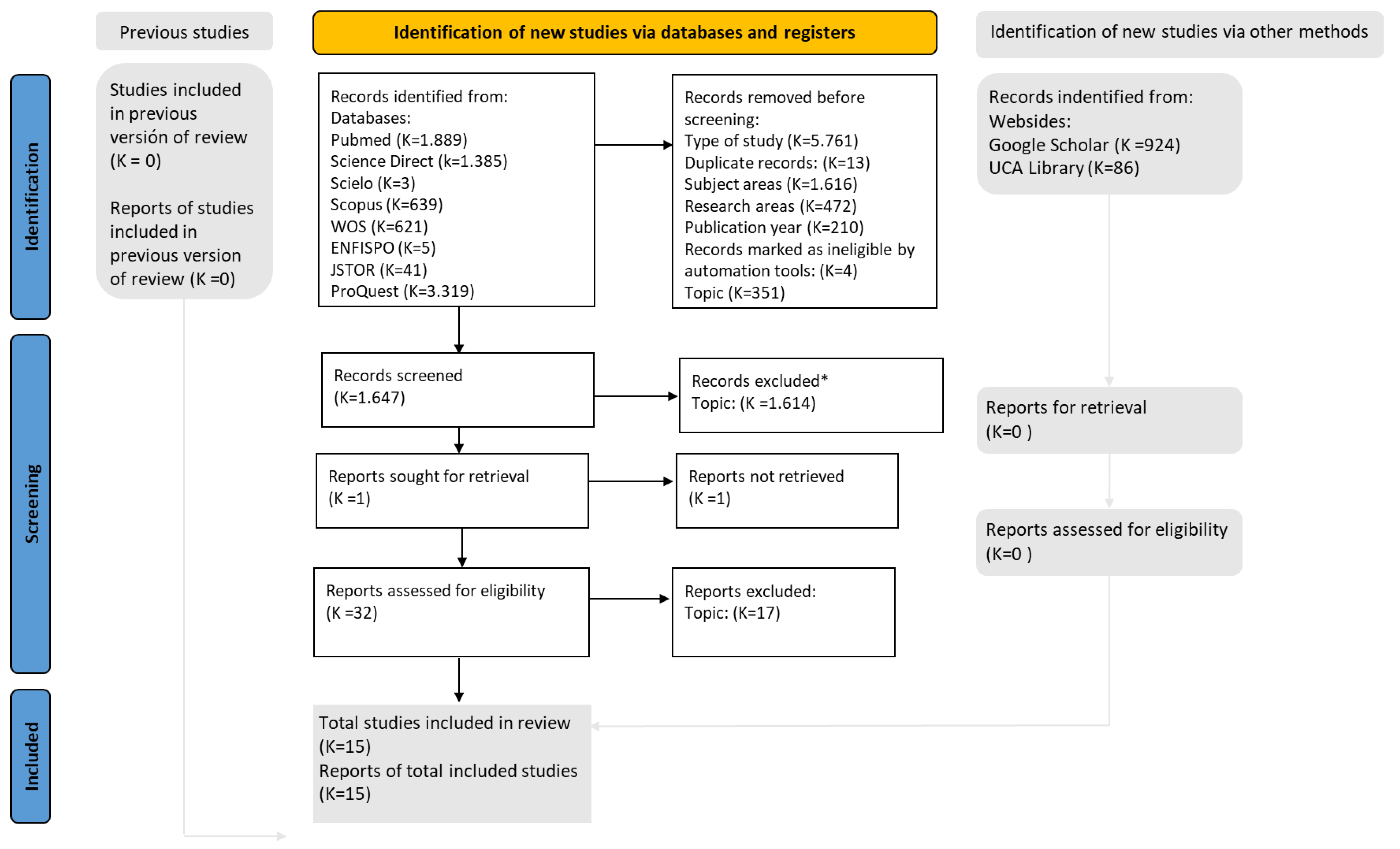

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

| Authors (Study Desing) | Participants | Intervention | Total Time | Variables | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elfassy, C. et al. [20], 2020. (Qualitative study based on grounded theory) | n = 27 ± 14–21 years old. G1 1: n = 6 ± Young people with arthrogryposis. G2 2: n = 11 ± Carers. G3 3: n = 10 ± Health professionals. | Interviews were conducted in person or by telephone and were digitally recorded and transcribed for later analysis. | 12 months. | CMOP-E 4: Elements on physical, cognitive, affective, environmental, occupational, national performance and activity, activity domains and participation. | Rehabilitation is beneficial from early childhood to late adolescence, as it helps to determine future treatment. Early initiation of rehabilitation is necessary. |

| Gagnon, M. et al. [25], 2021. (Single cohort study) | n = 10 ± 8–21 years old. | Individualised exercise programme carried out at home, conducted remotely using telerehabilitation. | 4 months. | APPT 5: Pain. GAS 6 PAQ-A 7: Physical activity. PODCI 8: Function. ROM 9: Joint range. | Statistically significant improvements were recorded for the pain and comfort domain, physical activity and function after intervention. |

| Valdés-Flores, M. et al. [18], 2016. (Cross-sectional study) | n = 50 ± 0–7 years old. n = 22 ± Men. n = 28 ± Women. | Specific rehabilitation and physiotherapy programmes for patients referred to the Genetics Department of the referred to the Genetics Department of the National Rehabilitation Institute of Mexico with a presumptive diagnosis of AMC. | 36 months. | Variety of diagnostic tests: physical and radiographic examinations, pregnancy and delivery data, family medical history and karyotype. | The importance of such programmes and the need for a multidisciplinary approach to improve these patients were multidisciplinary approach to improve these patients. |

| Rojo Osuna, DJ. et al. [13], 2016. (Case series study) | n = 17 ± 10 months-16 years old n = 8 ± Men. n = 9 ± Women. | The records of patients with a diagnosis of AMC. | 24 months. | Charting: To evaluate phenotypic characteristics reported in clinical records. | When arthrogryposis is diagnosed, treatment by a multidisciplinary team is essential. Amyloplasia is the most common type of AMC. |

| Gür, G. et al. [7], 2016. (Case report study) | n = 2. Case 1: 7-month-old baby. Case 2: 6-month-old infant. | Serial orthopaedic treatment was applied to reduce bilateral knee flexion contractures. | 12 months. | GMFCS 10: Ambulatory capacity of children. Universal goniometry: Range of motion of joints. | Bilateral passive extension limitation improved; in the first case, the increase in passive extension range was 75°, and in the second case it was 45°. |

| Hernández Antúnez, N. et al. [14], 2015. (Case series study) | n = 19: n = 14 ± Men. n = 5 ± Women. | Physiotherapy and transfer training | 60 months. | WeeFIM 11: Severity of disability and functionality in an objective manner. Data recording form: Sociodemographic and clinical variables, related to the treatments carried out and functionality. | Good scores were in cognitive and behavioural areas. Most of the children achieved independent walking, thanks to physiotherapy treatment. |

| Azbell, K. et al. [8], 2015. (Case report study) | n = 1 ± NB 12 11-day-old. | Regular home (parents) and clinic (physiotherapist and occupational therapist) programme of stretching, strengthening, splinting, casting and bilateral Achilles tenotomies. | 9 months. | PSFS 13: Functional changes and patient involvement. PDMS-2 14: Fine and gross motor skills. Norkin method: passive ROM 9. FLACC 15: Pain. | Improvements were observed in all components of the ICF 16. Its total score improved by 2.34 points. |

| Ayadi, K. et al. [15], 2015. (Case series study) | n = 23 ± Average age of 6.6 years n = 13 ± Men. n = 10 ± Women. | The records of children with AMC in the orthopaedic department of the Habib-Bourguiba University Hospital Centre in Sfax (Tunisia) were reviewed. Treatments were not specified | 144 months. | PODCI 8: Upper limb function, transfers and mobility, sport participation, pain, happiness and general function. | As a result of the treatments, an average functional score of 69.57 was obtained. Multidisciplinary care is necessary and should be provided early and continuously. |

| Águila Tejeda, G. et al. [9], 2013. (Case report study) | n = 1 ± 8-year-old girl. | Physiotherapy and psychotherapy (with family support). Rehabilitation was carried out at the CEPROMEDE 17. The physiotherapy treatment consisted of: breathing exercises, thermotherapy, massage, kinesitherapy, electrotherapy and adaptation to BADL 18. | 72 months. | Morpho-functional assessment of the patient and evaluation of the results after the treatments applied. | Lower limb limitations improved by 80% with physiotherapy and rehabilitation treatment, as well as quality of life, ambulation and performance of BADL. |

| Binkiewicz-Glinska, A. et al. [10], 2013. (Case report study) | n = 1 ± NB 3-weeks-old. | Physiotherapy based on massage therapy, kinesitherapy (wrist and fingers), positional therapy, proprioception and sucking reflex stimulation | 6 months. | ROM. | Improved range of motion and functionality of shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip and knee joints through early rehabilitation, comprehensive and multidisciplinary rehabilitation. |

| Beetar, P. [11], 2011. (Case report study) | n = 1 ± 2- month-old girl. | Physiotherapy with the help of the child’s mother. The routine consisted of kinesiotherapy, mat exercises for motor development, proprioception and gait training. | 120 months. | Various diagnostic tests: X-rays, muscle biopsies, electrophysiological studies, genetic studies or magnetic resonance imaging. | Early initiation of physiotherapy preserved and restored joint mobility, muscle tone and proprioception. |

| Dillon, ER. et al. [19], 2009. (Cross-sectional study) | n = 26 ± 5–18 years old. G1 y G2: n = 8 ± Men. n = 5 ± Women. G1: n = 4 ± Distal arthrogryposis. n = 9 ± Amyoplasia. G2: n = 13 ± Typical development. | Young people with amyloplasia or distal or distal arthrogryposis, and youngsters with typical development of the same age and sex. | 7 days. | Activity Monitor Step Watch 3: Frequency, duration, intensity of ambulatory activity and daily steps. Activity scale for children and performance questionnaires: Compares activity levels presented by the Step Watch 3. | Thanks to surgical interventions and rehabilitation, most of the children became ambulant, achieved relative independence in BADL and even attended school. |

| Taricco, LD. et al. [12], 2009. (Case report study) | n = 1 ± 35-year-old woman. | 15 sessions of physiotherapy, 5 sessions of hydrotherapy, 2 sessions of occupational therapy, 2 sessions of psychotherapy and 1 session of art therapy. 45 minutes 5 days a week. | 15 months. | VAS 19: Pain. Universal Goniometer: Range of motion of joints. | It is essential that orthopaedic and rehabilitative treatment and planning be carried out by an interdisciplinary team. |

| Morcuende, JA. et al. [16], 2008. (Case series study) | n = 16 ± 10 months-12 years old n = 11 ± Men. n = 5 ± Women. | Records of patients with clubfoot associated with arthrogryposis are reviewed. Ponseti’s method was performed in all these patients. | 144 months. | Patient’s age at first visit, previous treatment, number of casts used, possible surgeries and degree of ankle dorsiflexion after tenotomy were assessed. | The Ponseti method is very effective for early correction of clubfoot associated with arthrogryposis; it reduces the need for extensive corrective surgeries or talectomies. |

| De Miguel Benadiba, C. et al. [17], 1992. (Case series study) | n = 24 ± Average age 11.1 years n = 14 ± Men. n = 10 ± Women. | Physiotherapy by means of kinesitherapy and stretching, which were used before and after orthopaedic treatment. | 156 months. | Patient or family survey: functional capacity and social integration of patients. | Most patients become independent and able to advocate for themselves when they reach adulthood, thanks to early initiation of multidisciplinary treatment and family support. |

3.3. Methodological Quality Synthesis

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Langston, S.; Chu, A. Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita. Pediatr. Ann. 2020, 49, e299–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahan-Oliel, N.; Cachecho, S.; Barnes, D.; Bedard, T.; Davison, A.M.; Dieterich, K.; Donohoe, M.; Fąfara, A.; Hamdy, R.; Hjartarson, H.T.; et al. International Multidisciplinary Collaboration toward an Annotated Definition of Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulesa-Mrowiecka, M.; Piech, J.; Dowgierd, K.; Myśliwiec, A. Physical Therapy of Temporomandibular Disorder in a Child with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Case Report and Literature Review. CRANIO, 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Caporuscio, K.; Veilleux, L.; Hamdy, R.; Dahan-Oliel, N. Muscle and Joint Function in Children Living with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffman, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An Updated Guidelinefor Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Z.; Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E. The Updated Joanna Briggs Institute Model of Evidence-Based Healthcare. Int. J. Evid. Based. Healthc. 2019, 17, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, G.; Erel, S.; Yakut, Y.; Aksoy, C.; Uygur, F. One-Year Follow-up Study of Serial Orthotic Treatment in Two Cases with Arthrogrypotic Syndromes Who Have Bilateral Knee Flexion Contractures. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2016, 40, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azbell, K.; Dannemiller, L. A Case Report of an Infant With. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2015, 27, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Águila Tejeda, G.; Suárez Monzón, H.; Delgado Figueredo, R.; Suárez Collado, P.O. Proceso Rehabilitador de Artrogriposis Múltiple Congénita. Rev. Cuba. Ortop. Y Traumatol. 2013, 27, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Binkiewicz-Glinska, A.; Sobierajska-Rek, A.; Bakula, S.; Wierzba, J.; Drewek, K.; Kowalski, I.M.; Zaborowska-Sapeta, K. Arthrogryposis in Infancy, Multidisciplinary Approach: Case Report. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetar-Castro, P. Fisioterapia En Artrogriposis Múltiple Congénita: Caso Clínico. Cuest. Fisioter. 2011, 40, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Taricco, L.D.; Aoki, S.S. Rehabilitation of an Adult Patient with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita Treated with an External Fixator. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 88, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo Osuna, D.J.; Torres Flores, J. Descripción de Pacientes Con Artrogriposis Congénita En Un Centro de Fisioterapia Pediátrica En El Norte de México. Rev. Méd. Costa Rica Y Centroam. 2016, 73, 751–756. [Google Scholar]

- Antúnez Hernández, N.; González, C.; Cerisola, A.; Casamayou, D.; Barros, G.; De Castellet, L.; Camarot, T. Artrogriposis Múltiple Congénita. Rev. Méd. Del Urug. 2015, 31, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, K.; Trigui, M.; Abid, A.; Cheniour, A.; Zribi, M.; Keskes, H. L’arthrogrypose: Manifestations Cliniques et Prise En Charge. Arch. Pediatr. 2015, 22, 830–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcuende, J.A.; Dobbs, M.B.; Frick, S.L. Results of the Ponseti Method in Patients with Clubfoot Associated with Arthrogryposis. Iowa Orthop. J. 2008, 28, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel Benadiba, C.; Gil Agudo, A.; Salcedo Luengo, J.; Burgos Flores, J.; Amaya Alarcon, J. Enfoque Terapéutico de La Artrogriposis. Rehabilitation 1992, 26, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés-Flores, M.; Casas-Avila, L.; Hernández-Zamora, E.; Kofman, S.; Hidalgo-Bravo, A. Characterization of a Group Unrelated Patients with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita. J. Pediatr. 2016, 92, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, E.R.; Bjornson, K.F.; Jaffe, K.M.; Hall, J.G.; Song, K. Ambulatory Activity in Youth with Arthrogryposis: A Cohort Study. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2009, 29, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfassy, C.; Darsaklis, V.B.; Snider, L.; Gagnon, C.; Hamdy, R.; Dahan-Oliel, N. Rehabilitation Needs of Youth with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: Perspectives from Key Stakeholders. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2318–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, F.; Soledad, R.; Carolina, S.; Lerda, L.; María, A.; Metodológico, A. Protocolo de Atención Kinésica En Niños Con Artrogriposis Múltiple Congénita. Univ. Abierta Interam. 2003, 86, 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, H.A.; James, C.R.; Dendy, D.W.; Irwin, T.A.; Swiacki, C.A.; Thompson, L.D.; Camp, T.M.; Yang, H.S.; Cooper, K.J. Gait and Gross Motor Improvements in a Two-Year-Old Child With Arthrogryposis After Hippotherapy Intervention Using a Norwegian Fjord. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 67, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicollini-Panisson, R.D.; Hengles, R.C.; De Mattos, D.C.G. Atuação Da Fisioterapia Aquática Funcional No Deslocamento Na Postura Sentada Na Amioplasia Congênita: Relato de Caso. Sci. Med. 2015, 24, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, A.; Collins, J.; Sawatzky, B.; Hamdy, R.; Dahan-Oliel, N. Pain among Children and Adults Living with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2019, 181, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Collins, J.; Elfassy, C.; Marino Merlo, G.; Marsh, J.; Sawatzky, B.; Yap, R.; Hamdy, R.; Veilleux, L.-N.; Dahan-Oliel, N. A Telerehabilitation Intervention for Youths With Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: Protocol for a Pilot Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e18688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsch, K.; Pietrzak, S. Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita. Orthopade 2007, 36, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yu, X. Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: Classification, Diagnosis, Perioperative Care, and Anesthesia. Front. Med. 2017, 11, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Quiroz, P.; Yokoyama Rebollar, E. Abordaje Clínico y Diagnóstico de La Artrogriposis. Acta Pediátrica México 2019, 40, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Luan, W.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Qian, B.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Z. Improvement of Pulmonary Function in Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita Patients Undergoing Posterior Spinal Fusion Surgery for Concomitant Scoliosis: A Minimum of 3-Year Follow-Up. World Neurosurg. 2022, 157, e424–e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uehara, M.; Kosho, T.; Takano, K.; Inaba, Y.; Kuraishi, S.; Ikegami, S.; Oba, H.; Takizawa, T.; Munakata, R.; Hatakenaka, T.; et al. Proximal Junctional Kyphosis After Posterior Spinal Fusion for Severe Kyphoscoliosis in a Patient With PIEZO2-Deficient Arthrogryposis Syndrome. Spine 2020, 45, E600–E604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleich, S.J.; Tien, M.; Schroeder, D.R.; Hanson, A.C.; Flick, R.; Nemergut, M.E. Anesthetic Outcomes of Children with Arthrogryposis Syndromes: No Evidence of Hyperthermia. Anesth. Analg. 2017, 124, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giampietro, P.F.; Hall, J.G. 50 Years Ago in THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS: Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Clinical Investigation. J. Pediatr. 2020, 217, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gmuca, S.; Xiao, R.; Urquhart, A.; Weiss, P.F.; Gillham, J.E.; Ginsburg, K.R.; Sherry, D.D.; Gerber, J.S. The Role of Patient and Parental Resilience in Adolescents with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. J. Pediatr. 2019, 210, 118–126.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashcraft, L.E.; Asato, M.; Houtrow, A.J.; Kavalieratos, D.; Miller, E.; Ray, K.N. Parent Empowerment in Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Patient-Patient-Cent. Outcomes Res. 2019, 12, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, N.C.; de Almeida, C.S.; Smith, B.A. Effectiveness of a Home-Based Early Cognitive-Motor Intervention Provided in Daycare, Home Care, and Foster Care Settings: Changes in Motor Development and Context Affordances. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 151, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.A.; Wilson, K.S.; Castner, D.M.; Dumont-Driscoll, M.C. Changes in Health-Related Outcomes in Youth With Obesity in Response to a Home-Based Parent-Led Physical Activity Program. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2019, 65, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Gonzalo, V.; Pandiella Dominique, A.; Kürlander Arigón, G.; Simó Segovia, R.; Caballero, F.F.; Miret, M. Validación de La PDMS-2 En Población Española. Evaluación de La Intervención de Fisioterapia y La Participación de Los Padres En El Tratamiento de Niños Con Trastornos Del Neurodesarrollo. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 73, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toovey, R.A.M.; Harvey, A.R.; McGinley, J.L.; Lee, K.J.; Shih, S.T.F.; Spittle, A.J. Task-Specific Training for Bicycle-Riding Goals in Ambulant Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustad, T.; Fjørtoft, T.; Øberg, G.K. General Movement Optimality Score and General Movements Trajectories Following Early Parent-Administrated Physiotherapy in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 163, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, T.; Hegarty, F.; Powell, K.; Deasy, L.; Regan, M.O.; Sell, D. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Parent Led Therapist Supervised Articulation Therapy (PLAT) with Routine Intervention for Children with Speech Disorders Associated with Cleft Palate. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2020, 55, 639–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Haynes, S.C.; Favila-Meza, A.; Hoch, J.S.; Tancredi, D.J.; Bares, A.D.; Mouzoon, J.; Marcin, J.P. Parent Experience and Cost Savings Associated With a Novel Tele-Physiatry Program for Children Living in Rural and Underserved Communities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratte, G.; Couture, M.; Morin, M.; Berbari, J.; Tousignant, M.; Camden, C. Evaluation of a Web Platform Aiming to Support Parents Having a Child with Developmental Coordination Disorder: Brief Report. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2020, 23, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshanray, A.; Rayyani, M.; Dehghan, M.; Faghih, A. Comparative Effect of Mother’s Hug and Massage on Neonatal Pain Behaviors Caused by Blood Sampling: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2020, 66, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Yu, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Xiong, Y. The Positive Effect of Mother-Performed Infant Massage on Infantile Eczema and Maternal Mental State: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 10, 1068043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzopoulos, P.; Koutserimpas, C.; Begkas, D.; Markeas, N. An Educational Module for Pavlik Harness Application for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip: Study in a Greek Population. Kurume Med. J. 2019, 66, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutar Güven, Ş.; İşler Dalgiç, A.; Duman, Ö. Evaluation of the Efficiency of the Web-Based Epilepsy Education Program (WEEP) for Youth with Epilepsy and Parents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 111, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero-Pinto, E.; Romero-Galisteo, R.P.; Jiménez-Rejano, J.J.; Escobio-Prieto, I.; Peña-Salinas, M.; Luque-Moreno, C.; Palomo-Carrión, R. A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial on the Effectiveness of Infant Massage on the Acceptance, Commitment and Awareness of Influence in Parents of Babies with Down Syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2023, 67, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T. Important of Case-Reports/Series, in Rare Diseases: Using Neuroendocrine Tumors as an Example. World J. Clin. Cases 2014, 2, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampayo-Cordero, M.; Miguel-Huguet, B.; Malfettone, A.; Pérez-García, J.M.; Llombart-Cussac, A.; Cortés, J.; Pardo, A.; Pérez-López, J. The Value of Case Reports in Systematic Reviews from Rare Diseases. The Example of Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT) in Patients with Mucopolysaccharidosis Type II (MPS-II). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Results | Filters | Reviewed Articles | Selected Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed 1 | (“Arthrogryposis” [Mesh]) AND “Physical Therapy Modalities” [Mesh]) | |||

| 64 | Type of study | 2 | 1 | |

| ((“Arthrogryposis” [Mesh]) AND “Physical Therapy Modalities” [Mesh]) AND “Contracture” [Mesh]) | ||||

| 12 | - | 12 | 0 | |

| ((“Arthrogryposis” [Mesh]) AND “Rehabilitation” [Mesh]) | ||||

| 103 | Type of study | 12 | 1 | |

| ((“Arthrogryposis” [Mesh]) AND “Rehabilitation” [Mesh]) AND “Joints” [Mesh] | ||||

| 34 | Type of study | 34 | 0 | |

| ((“Arthrogryposis” [Mesh]) AND “Physical Therapy Modalities” [Mesh]) AND “Clubfoot” [Mesh] | ||||

| 10 | Type of study | 4 | 0 | |

| “Arthrogryposis AND Physical Therapy” | ||||

| 136 | Type of study | 4 | 2 | |

| “Physiotherapy in arthrogryposis” | ||||

| 971 | Type of study | 15 | 1 | |

| Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita AND treatment | ||||

| 376 | Type of study | 149 | 4 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 183 | Type of study | 3 | 0 | |

| ScienceDirect 2 | “Arthrogryposis AND Physical Therapy” | |||

| 1.385 | Type of study Subject areas | 302 20 | 2 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Scielo 3 | Fisioterapia en artrogriposis | |||

| 2 | - | 0 | 1 | |

| Arthrogryposis in physical therapy | ||||

| 1 | - | 0 | 1 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | - | 0 | 0 | |

| Scopus 4 | “Artrogriposis” | |||

| 69 | Type of study | 15 | 0 | |

| “Artrogriposis y fisioterapia” | ||||

| 2 | - | 0 | 1 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 568 | Subject area | 15 | 0 | |

| WOS 5 | Arthrogryposis AND physical therapy | |||

| 111 | Type of study | 30 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 510 | Research areas | 38 | 0 | |

| ENFISPO 6 | (Artrogriposis OR Artrogriposis–Fisioterapia OR Artrogriposis–Rehabilitacion OR Artrogriposis–Tratamiento OR Artrogriposis en niños–Fisio OR Artrogriposis en niños–Rehab) | |||

| 5 | - | 0 | 1 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| JSTOR 7 | Arthrogryposis AND Physical Therapy | |||

| 41 | Type of study | 32 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Google Schoolar | Fisioterapia en artrogriposis | |||

| 401 | Type of study | 386 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 523 | Publication year | 313 | 0 | |

| UCA Library 8 | Artrogriposis múltiple congénita tratamiento | |||

| 39 | Type of study | 31 | 0 | |

| Artrogriposis y contractura | ||||

| 47 | Type of study | 39 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ProQuest Research Library | Artrogriposis | |||

| 249 | Type of study | 26 | 0 | |

| Physical therapy in arthrogryposis | ||||

| 3.070 | Type of study | 444 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 1.159 | Tipo de estudio | 58 | 0 | |

| Cochrane Library | Arthrogryposis | |||

| 0 | - | 0 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 3 | - | 0 | 0 | |

| EBSCO 9 | Artrogriposis | |||

| 0 | - | 0 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | - | 0 | 0 | |

| PEDro 10 | Arthrogryposis | |||

| 0 | - | 0 | 0 | |

| (Arthrogryposis OR “Arthrogryposis multiplex congénita” OR Artrogriposis OR “Artrogriposis múltiple congénita”) AND (“Physical Therapy Modalities” OR Rehabilitation OR Physiotherapy OR Fisioterapia OR treatment OR “physical therapy” OR Rehabilitación OR Tratamiento OR Rehab* OR Fisio*) AND (Contracture OR Joints OR Clubfoot OR contractura) | ||||

| 0 | 0 | |||

| TOTAL | 10.074 | - | 1.984 | 15 |

| JBI Items/Studies | Aguila Tejada et al., 2013 [9] | Azbell et al., 2015 [8] | Beetar et al., 2011 [11] | Binkiewicz-Glinska et al., 2013 [10] | Gür et al., 2016 [7] | Taricco et al., 2009 [12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| U | Y | U | Y | U | Y |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| N | N | N | N | N | N |

| N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| JBI Items/Studies | Ayadi et al., 2015 [15] | De Miguel Benadabia et al., 1992 [17] | Hernández Antúnez et al., 2015 [14] | Morcuende et al., 2008 [16] | Rojo-Osuna et al., 2016 [13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | U | Y | U | U |

| Y | U | Y | Y | U |

| Y | U | Y | U | U |

| Y | U | Y | Y | U |

| Y | U | Y | U | U |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| U | U | U | Y | U |

| U | U | U | U | U |

| Y | U | U | U | U |

| JBI Items/Studies | Dillon et al., 2009 [19] | Valdes-Flores et al., 2016 [18] |

|---|---|---|

| Y | U |

| Y | Y |

| Y | Y |

| Y | Y |

| U | U |

| U | U |

| Y | Y |

| Y | Y |

| JBI Items/Studies | Efassy et al., 2009 [20] |

|---|---|

| Y |

| Y |

| Y |

| Y |

| N |

| N |

| Y |

| Y |

| Y |

| JBI Items/Studies | Gagnon et al., 2021 [25] |

|---|---|

| Y |

| Y |

| U |

| Y |

| Y |

| N |

| U |

| Y |

| U |

| U |

| Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García Aguilar, C.E.; García-Muñoz, C.; Carmona-Barrientos, I.; Vinolo-Gil, M.J.; Martin-Vega, F.J.; Gonzalez-Medina, G. Rehabilitation in Patients Diagnosed with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10, 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050768

García Aguilar CE, García-Muñoz C, Carmona-Barrientos I, Vinolo-Gil MJ, Martin-Vega FJ, Gonzalez-Medina G. Rehabilitation in Patients Diagnosed with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Systematic Review. Children. 2023; 10(5):768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050768

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía Aguilar, Catalina E., Cristina García-Muñoz, Ines Carmona-Barrientos, Maria Jesus Vinolo-Gil, Francisco Javier Martin-Vega, and Gloria Gonzalez-Medina. 2023. "Rehabilitation in Patients Diagnosed with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Systematic Review" Children 10, no. 5: 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050768

APA StyleGarcía Aguilar, C. E., García-Muñoz, C., Carmona-Barrientos, I., Vinolo-Gil, M. J., Martin-Vega, F. J., & Gonzalez-Medina, G. (2023). Rehabilitation in Patients Diagnosed with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita: A Systematic Review. Children, 10(5), 768. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050768