Association between Soccer Participation and Liking or Being Proficient in It: A Survey Study of 38,258 Children and Adolescents in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Division

2.3. Selection of Questions

2.4. Proceduce

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

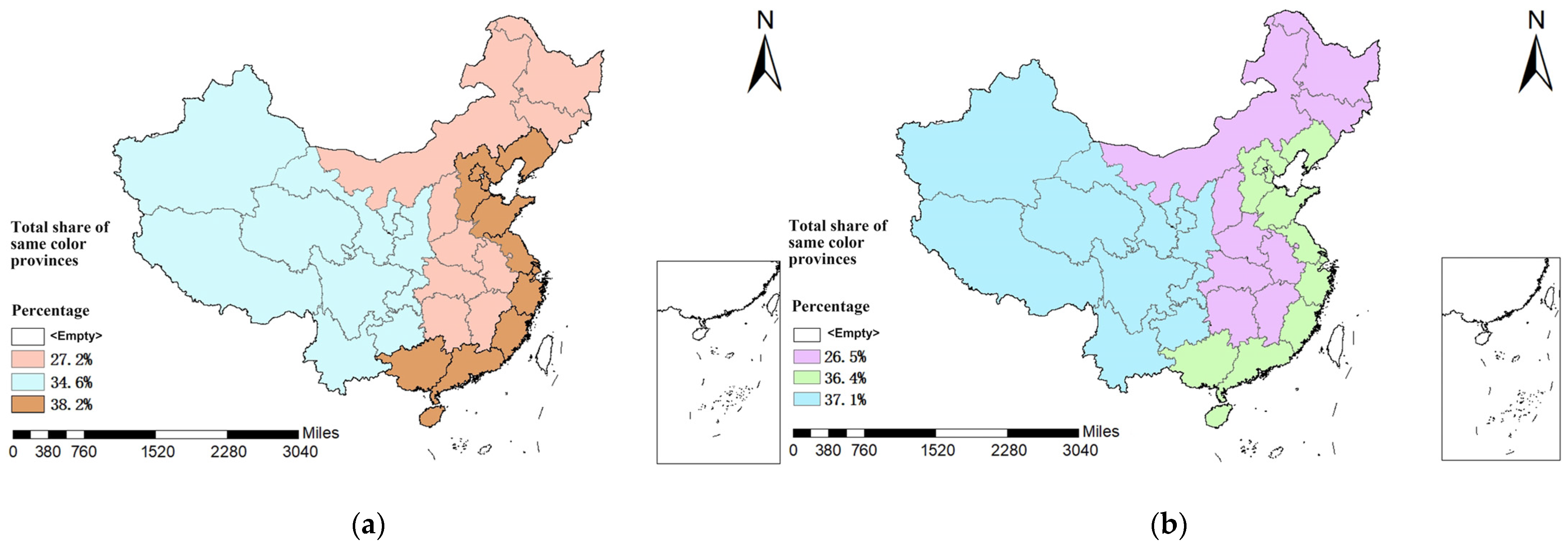

3.1. Overview of the Distribution of the Three Major Divisions

3.2. Uneven Distribution across Regions with a Strong Correlation with the Natural Environment of Each Region

3.3. Correlation Factors Affecting Children and Adolescents’ Participation in Soccer

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janda, D.H.; Bir, C.A.; Cheney, A.L. An evaluation of the cumulative concussive effect of soccer heading in the youth population. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2002, 9, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Wan, B.; Bu, T.; Luo, Y.; Ma, W.; Huang, S.; Gang, L.; Deng, W.; Liu, Z. Chinese physical fitness standard for campus football players: A pilot study of 765 children aged 9 to 11. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1023910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giulianotti, R.; Robertson, R. The globalization of football: A study in the glocalization of the ‘serious life’. Br. J. Sociol. 2004, 55, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Sprot of China. Steadily Promote Healthy and Orderly-2014 Campus Football. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n20001280/n20745751/n20767277/c21438835/content.html (accessed on 5 December 2022). (In Chinese)

- Hulteen, R.M.; Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Barnett, L.M.; Hallal, P.C.; Colyvas, K.; Lubans, D.R. Global participation in sport and leisure-time physical activities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2017, 95, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The General Office of the State Council issued a Notice on the Overall Plan for the Reform and Development of Chinese Football. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-03/16/content_9537.htm (accessed on 5 December 2022). (In Chinese)

- General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Several Opinions of The State Council on Accelerating the Anti-War Sports Exhibition Industry to Promote Sports Consumption. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-10/20/content_9152.htm (accessed on 5 December 2022). (In Chinese)

- Ministry of Education of the people’s Republic of China. The Ministry of Education and Other Six Departments on Accelerating the Development of Youth Suggestions on the Implementation of Campus Football. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A17/moe_938/s3276/201501/t20150112_189308.html (accessed on 5 December 2022). (In Chinese)

- Oja, P.; Titze, S.; Kokko, S.; Kujala, U.M.; Heinonen, A.; Kelly, P.; Koski, P.; Foster, C. Health benefits of different sport disciplines for adults: A systematic review of observational and intervention studies with meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabra, A.; Katzmarzyk, P.; Carvalho, M.J.; Seabra, A.; Coelho-E-Silva, M.; Abreu, S.; Vale, S.; Póvoas, S.; Nascimento, H.; Belo, L.; et al. Effects of 6-month soccer and traditional physical activity programmes on body composition, cardiometabolic risk factors, inflammatory, oxidative stress markers and cardiorespiratory fitness in obese boys. J. Sports Sci. 2016, 34, 1822–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seabra, A.; Marques, E.; Brito, J.; Krustrup, P.; Abreu, S.; Oliveira, J.; Rego, C.; Mota, J.; Rebelo, A. Muscle strength and soccer practice as major determinants of bone mineral density in adolescents. Jt. Bone Spine 2012, 79, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L.; Radnor, J.M.; Rhodes, B.C.; Faigenbaum, A.D.; Myer, G.D. Relationships between functional movement screen scores, maturation and physical performance in young soccer players. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 33, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krustrup, P.; Williams, C.A.; Mohr, M.; Hansen, P.R.; Helge, E.W.; Elbe, A.-M.; De Sousa, M.; Dvorak, J.; Junge, A.; Hammami, A.; et al. The “Football is Medicine” platform-scientific evidence, large-scale implementation of evidence-based concepts and future perspectives. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28 (Suppl. S1), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaller, P.H.; Fürmetz, J.; Chen, F.; Degen, N.; Manz, K.M.; Wolf, F. Bowlegs and Intensive Football Training in Children and Adolescents. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2018, 115, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.N.; Elbe, A.-M.; Madsen, M.; Madsen, E.E.; Ørntoft, C.; Ryom, K.; Dvorak, J.; Krustrup, P. An 11-week school-based ‘health education through football programme’ improves health knowledge related to hygiene, nutrition, physical activity and well-being—And it’s fun! A scaled-up, cluster-RCT with over 3000 Danish school children aged 10–12 years old. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, M.; Elbe, A.; Madsen, E.E.; Ermidis, G.; Ryom, K.; Wikman, J.M.; Lind, R.R.; Larsen, M.N.; Krustrup, P. The “11 for Health in Denmark” intervention in 10- to 12-year-old Danish girls and boys and its effects on well-being—A large-scale cluster RCT. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krustrup, P.; Nielsen, J.J.; Krustrup, B.; Christensen, J.F.; Pedersen, H.; Randers, M.B.; Aagaard, P.; Petersen, A.-M.; Nybo, L.; Bangsbo, J. Recreational soccer is an effective health-promoting activity for untrained men. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faude, O.; Kerper, O.; Multhaupt, M.; Winter, C.; Beziel, K.; Junge, A.; Meyer, T. Football to tackle overweight in children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Goenka, S. Built environment for physical activity—An urban barometer, surveillance, and monitoring. Obes. Rev. 2019, 21, e12938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.-K.; Kang, D.; Choi, J.-Y. Correlates associated with participation in physical activity among adults: A systematic review of reviews and update. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.E.; Reis, R.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Wells, J.C.; Loos, R.J.F.; Martin, B.W.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet 2012, 380, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, N.; Humpel, N.; Owen, N.; Leslie, E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity A review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Craike, M.J.; Symons, C.M.; Payne, W.R. Family support and ease of access link socio-economic status and sports club membership in adolescent girls: A mediation study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurka, J.M.; Adams, M.A.; Todd, M.; Colburn, T.; Sallis, J.F.; Cain, K.L.; Glanz, K.; Frank, L.D.; Saelens, B.E. Patterns of neighborhood environment attributes in relation to children’s physical activity. Health Place 2015, 34, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boone-Heinonen, J.; Roux, A.V.D.; Kiefe, C.I.; Lewis, C.E.; Guilkey, D.K.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Neighborhood socioeconomic status predictors of physical activity through young to middle adulthood: The CARDIA study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, G. When Will China Win the World Cup? A Study of China’s Youth Football Development. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2017, 34, 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, I.; Hughes, D.C.; Greeves, J.P.; Fraser, W.D.; Sale, C. Increased Training Volume Improves Bone Density and Cortical Area in Adolescent Football Players. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanfeng, Z.; Chong-min, J.; Rui, C.; Dong-ming, W.; Ji-jing, L. Regional Characteristics of the National Physical Activity Level in China. China Sport Sci. 2012, 32, 3–10+22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wei, M.; Wei, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Xiang, K.; Feng, Y.; Yin, G. Preoperatively Predicting the Central Lymph Node Metastasis for Papillary Thyroid Cancer Patients with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 713475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Chen, W.Z.; Li, Y.C.; Chen, J.; Zeng, Z.Q. Sleep and hypertension. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2020 National Fitness Activity Status Survey Bulletin. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n315/n329/c24335053/content.html (accessed on 3 March 2022). (In Chinese)

- Barnett, L.M.; Morgan, P.J.; Van Beurden, E.; Beard, J.R. Perceived sports competence mediates the relationship between childhood motor skill proficiency and adolescent physical activity and fitness: A longitudinal assessment. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Cliff, D.P.; Barnett, L.M.; Okely, A.D. Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents: Review of associated health benefits. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 1019–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahov, E.; Baghurst, T.M.; Mwavita, M. Preschool Motor Development Predicting High School Health-Related Physical Fitness: A Prospective Study. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2014, 119, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Lai, S.K.; Veldman, S.L.C.; Hardy, L.L.; Cliff, D.P.; Morgan, P.J.; Zask, A.; Lubans, D.R.; Shultz, S.P.; Ridgers, N.D.; et al. Correlates of Gross Motor Competence in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1663–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petlichkoff, L.M. Youth Sport Participation and Withdrawal: Is It Simply a Matter of FUN? Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 1992, 4, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, T.K.; Carpenter, P.J.; Simons, J.P.; Schmidt, G.W.; Keeler, B. An Introduction to the Sport Commitment Model. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1993, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galobardes, B.; Lynch, J.; Smith, G.D. Measuring socioeconomic position in health research. Br. Med. Bull. 2007, 81–82, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumuid, D.; Olds, T.S.; Lewis, L.K.; Maher, C. Does home equipment contribute to socioeconomic gradients in Australian children’s physical activity, sedentary time and screen time? BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelishadi, R.; Qorbani, M.; Motlagh, M.E.; Ardalan, G.; Heshmat, R.; Hovsepian, S. Socioeconomic Disparities in Dietary and Physical Activity Habits of Iranian Children and Adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV Study. Arch. Iran. Med. 2016, 19, 530–537. [Google Scholar]

- Toftegaard-Støckel, J.; Nielsen, G.A.; Ibsen, B.; Andersen, L.B. Parental, socio and cultural factors associated with adolescents’ sports participation in four Danish municipalities. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, Y.; Wang, L.; Cao, Z.-B.; Chen, P. Physical activity, screen viewing time, and overweight/obesity among Chinese children and adolescents: An update from the 2017 physical activity and fitness in China—The youth study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, P. Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Dev. 1985, 56, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Fredricks, J.A. Family Socialization, Gender, and Sport Motivation and Involvement. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2005, 27, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, J.E.; Sarrazin, P.G.; Brustad, R.J.; Trouilloud, D.O.; Cury, F. Elementary schoolchildren’s perceived competence and physical activity involvement: The influence of parents’ role modelling behaviours and perceptions of their child’s competence. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2005, 6, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z.; Feng, D.; Liu, Y.; Esperat, M.C. Sedentary Behaviors among Hispanic Children: Influences of Parental Support in a School Intervention Program. Am. J. Health Promot. 2012, 26, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, B.P.; Orr, M.; Kellison, T. Sport Ecology: Conceptualizing an Emerging Subdiscipline Within Sport Management. J. Sport Manag. 2020, 34, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnode, C.D.; Lytle, L.A.; Erickson, D.J.; Sirard, J.R.; Barr-Anderson, D.; Story, M. The relative influence of demographic, individual, social, and environmental factors on physical activity among boys and girls. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaykamp, G.; Oldenkamp, M.; Breedveld, K. Starting a sport in the Netherlands: A life-course analysis of the effects of individual, parental and partner characteristics. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2012, 48, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Jamner, M.S.; Cooper, D.M. Assessing the perceived environment among minimally active adolescent girls: Validity and relations to physical activity outcomes. Am. J. Health Promot. 2003, 18, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudrak, J.; Slepicka, P.; Slepickova, I. Sport motivation and doping in adolescent athletes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.; Stronks, K.; Maas, J.; Wingen, M.; Kunst, A.E. Social neighborhood environment and sports participation among Dutch adults: Does sports location matter? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.; Saunders, T.J.; Bremer, E.; Tremblay, M.S. Long-term importance of fundamental motor skills: A 20-year follow-up study. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2014, 31, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicher, T.J.; Rice, J.A.; Hambrick, M.E. Understanding the Relationship Between Motivation, Sport Involvement and Sport Event Evaluation Meanings as Factors Influencing Marathon Participation. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2017, 2, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, S.; Kemp, L.; Bunde-Birouste, A.; MacKenzie, J.; Evers, C.; Shwe, T.A. “We wouldn’t of made friends if we didn’t come to Football United”: The impacts of a football program on young people’s peer, prosocial and cross-cultural relationships. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Song, Y. What Affects Sports Participation and Life Satisfaction Among Urban Residents? The Role of Self-Efficacy and Motivation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 884953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age Group | Participated in Sports and Exercise Programs (People) | Participated in Soccer Sports Programs (People) | Liking or Proficiency in Physical Exercise Programs (People) | Liking or Proficiency in Soccer Sports Programs (People) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7–9 years | 9290 | 2106 | 8569 | 1224 |

| 10–12 years | 9488 | 2567 | 16,542 | 1456 |

| 13–18 years | 16,875 | 4082 | 16,425 | 2194 |

| Three Regions | Provinces, Cities, Autonomous Regions and Municipalities Directly under the Central Government |

|---|---|

| Eastern Region | Beijing, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hebei, Jiangsu, Liaoning, Shandong, Shanghai, Tianjin, Zhejiang |

| Central Region | Anhui, Heilongjiang, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Inner Mongolia, Jiangxi, Jilin, Shanxi |

| Western Region | Chongqing, Gansu, Guizhou, Ningxia, Qinghai, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Tibet, Xinjiang, Yunnan |

| Level | Code | Question | Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | Daily participation in sports is soccer | 1 = Yes, 2 = No | |

| Family | Y1 | Have you purchased any sports-related products or services for your child in the past year? | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| Y2 | Do the parents live with the child? | 1 = Yes, 2 = No | |

| Y3 | An issue that is often discussed at home is soccer | 1 = Yes, 2 = No | |

| Y4 | Do your parents often encourage you to participate in sports and activities? | 1 = Yes, 2 = No | |

| School | Y5 | Will you keep doing the exercise program you learned in school? | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| community | Y6 | How convenient is it to go from your home to a nearby venue suitable for you and your friends to exercise? | 1 = very convenient, 2 = more convenient, 3 = average, 4 = not very convenient, 5 = very inconvenient |

| Y7 | How satisfied are you with the sports facilities in your community or village? | 1 = very satisfied, 2 = more satisfied, 3 = average, 4 = not very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied | |

| Y8 | The degree of security in your home community or village | 1 = very safe, 2 = more safe, 3 = average, 4 = not very safe, 5 = very unsafe | |

| Individual | Y9 | For the last year, the sport that has been consistently practiced is soccer | 1 = Yes, 2 = No |

| Y10 | Physical exercise can help you find more friends | 1 = absolutely agree, 2 = somehow agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = somehow disagree, 5 = absolutely disagree | |

| Y11 | Physical exercise can help you lose weight | 1 = absolutely agree, 2 = somehow agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = somehow disagree, 5 = absolutely disagree |

| Age Group | Participation | Liking or Proficiency | Participation and Liking or Proficiency | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Χ2 | p | % | Χ2 | p | Χ2 | p | ||

| Eastern Region | 7–9 | 24.7 | 12.295 | <0.001 | 14.0 | 4.21 | 0.040 | 133.191 | <0.001 |

| 10–12 | 28.4 | 15.7 | 164.891 | <0.001 | |||||

| 7–9 | 24.7 | 0.177 | 0.674 | 14.0 | 3.709 | 0.054 | |||

| 13–18 | 25.1 | 12.6 | 292.871 | <0.001 | |||||

| 10–12 | 28.4 | 12.096 | 0.001 | 15.7 | 17.766 | <0.001 | |||

| 13–18 | 25.1 | 12.6 | |||||||

| Central Region | 7–9 | 21.1 | 11.901 | 0.001 | 12.3 | 1.463 | 0.226 | 71.658 | <0.001 |

| 10–12 | 25.2 | 13.4 | 119.796 | <0.001 | |||||

| 7–9 | 21.1 | 3.325 | 0.068 | 12.3 | 0.009 | 0.924 | |||

| 13–18 | 23.0 | 12.4 | 194.418 | <0.001 | |||||

| 10–12 | 25.2 | 4.588 | 0.032 | 13.4 | 1.716 | 0.19 | |||

| 13–18 | 23.0 | 12.4 | |||||||

| Western Region | 7–9 | 21.5 | 30.432 | <0.001 | 12.9 | 18.077 | <0.001 | 80.919 | <0.001 |

| 10–12 | 27.5 | 16.7 | 107.965 | <0.001 | |||||

| 7–9 | 21.5 | 8.932 | 0.003 | 12.9 | 4.421 | 0.036 | |||

| 13–18 | 24.3 | 14.5 | 186.419 | <0.001 | |||||

| 10–12 | 27.5 | 11.266 | 0.001 | 16.7 | 7.836 | 0.005 | |||

| 13–18 | 24.3 | 14.5 | |||||||

| National | 7–9 | 22.7 | 40.866 | <0.001 | 13.2 | 19.042 | <0.001 | 284.616 | <0.001 |

| 10–12 | 27.2 | 15.4 | 389.773 | <0.001 | |||||

| 7–9 | 22.7 | 3.826 | 0.050 | 13.2 | 0.021 | 0.884 | |||

| 13–18 | 24.2 | 13.2 | 665.182 | <0.001 | |||||

| 10–12 | 27.2 | 28.365 | <0.001 | 15.4 | 23.629 | <0.001 | |||

| 13–18 | 24.2 | 13.2 | |||||||

| 7–18 | Eastern Region | 25.9 | 24.39 | <0.001 | 13.9 | 7.494 | 0.006 | 587.22 | <0.001 |

| Central Region | 23.1 | 12.6 | 384.106 | <0.001 | |||||

| Eastern Region | 25.9 | 7.662 | 0.006 | 13.9 | 3.271 | 0.071 | |||

| Western Region | 24.4 | 14.7 | 374.491 | <0.001 | |||||

| Central Region | 23.1 | 5.263 | 0.022 | 12.6 | 19.457 | <0.001 | |||

| Western Region | 24.4 | 17.7 | |||||||

| National | 24.6 | 13.8 | 374.491 | <0.001 | |||||

| Aged 7–9 | Aged 10–12 | Aged 13–18 | Aged 7–18 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation | Liking or Proficiency | Participation | Liking or Proficiency | Participation | Liking or Proficiency | Participation | Liking or Proficiency | ||

| National | X | 0.430 * | 0.355 * | 0.403 * | 0.186 | 0.113 | −0.088 | 0.314 | 0.138 |

| Y | 0.165 | 0.258 | 0.156 | 0.353 | 0.472 ** | 0.638 * | 0.315 | 0.487 * | |

| Z | −0.109 | −0.171 | −0.132 | −0.333 | −0.365 * | −0.449 * | −0.241 | −0.367 * | |

| Eastern Region | X | 0.651 * | 0.641 * | 0.641 * | 0.514 | 0.597 | 0.494 | 0.652 * | 0.591 * |

| Y | 0.016 | −0.017 | 0.154 | 0.069 | 0.266 | 0.253 | 0.159 | 0.100 | |

| Z | 0.347 | 0.049 | 0.250 | −0.095 | 0.251 | −0.071 | 0.296 | −0.039 | |

| Central Region | X | −0.088 | −0.055 | −0.023 | −0.159 | −0.190 | −0.330 | −0.129 | −0.237 |

| Y | 0.545 | 0.639 | 0.492 | 0.795 * | 0.804 ** | 0.882 ** | 0.691 * | 0.850 ** | |

| Z | −0.735 * | −0.694 * | −0.723 * | −0.755 * | −0.717 * | −0.620 * | −0.753 * | −0.709 * | |

| Western Region | X | −0.013 | −0.188 | 0.385 | −0.132 | 0.288 | 0.052 | 0.246 | 0.086 |

| Y | 0.380 | 0.466 | 0.099 | 0.409 | 0.338 | 0.589 | 0.326 | 0.543 | |

| Z | −0.287 | −0.139 | −0.022 | −0.061 | −0.395 | −0.525 | −0.303 | −0.461 | |

| Level | Variables | β | Wald | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Y1 | 0.563 | 457.197 | 0.000 | 1.756 | 1.668 | 1.849 |

| Y2 | 0.177 | 12.987 | 0.000 | 1.194 | 1.084 | 1.314 | |

| Y3 | 2.247 | 5400.495 | 0.000 | 0.106 | 0.100 | 0.112 | |

| Y4 | 0.627 | 05.371 | 0.020 | 1.871 | 1.102 | 3.179 | |

| School | Y5 | 0.394 | 105.310 | 0.000 | 0.675 | 0.626 | 0.727 |

| Community | Y6-1 | 0.558 | 27.326 | 0.000 | 1.748 | 1.418 | 2.155 |

| Y6-2 | 0.336 | 9.990 | 0.002 | 1.399 | 1.136 | 1.723 | |

| Y7-1 | 0.350 | 13.757 | 0.000 | 1.419 | 1.179 | 1.707 | |

| Y7-2 | 0.238 | 6.502 | 0.011 | 1.269 | 1.057 | 1.523 | |

| Y8 | 0.316 | 13.138 | 0.000 | 0.729 | 0.614 | 0.865 | |

| Individual | Y9 | 4.104 | 5781.784 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.015 | 0.018 |

| Y10 | 0.439 | 19.834 | 0.000 | 0.645 | 0.532 | 0.782 | |

| Y11 | 0.455 | 8.705 | 0.003 | 0.634 | 0.469 | 0.858 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Pan, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; Deng, P.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, A.; He, J.; Zhang, Y. Association between Soccer Participation and Liking or Being Proficient in It: A Survey Study of 38,258 Children and Adolescents in China. Children 2023, 10, 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030562

Gao Y, Pan X, Wang H, Wu D, Deng P, Jiang L, Zhang A, He J, Zhang Y. Association between Soccer Participation and Liking or Being Proficient in It: A Survey Study of 38,258 Children and Adolescents in China. Children. 2023; 10(3):562. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030562

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yibo, Xiang Pan, Huan Wang, Dongming Wu, Pengyu Deng, Lupei Jiang, Aoyu Zhang, Jin He, and Yanfeng Zhang. 2023. "Association between Soccer Participation and Liking or Being Proficient in It: A Survey Study of 38,258 Children and Adolescents in China" Children 10, no. 3: 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030562

APA StyleGao, Y., Pan, X., Wang, H., Wu, D., Deng, P., Jiang, L., Zhang, A., He, J., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Association between Soccer Participation and Liking or Being Proficient in It: A Survey Study of 38,258 Children and Adolescents in China. Children, 10(3), 562. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030562