A Preliminary Longitudinal Study on Infant-Directed Speech (IDS) Components in the First Year of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Materials

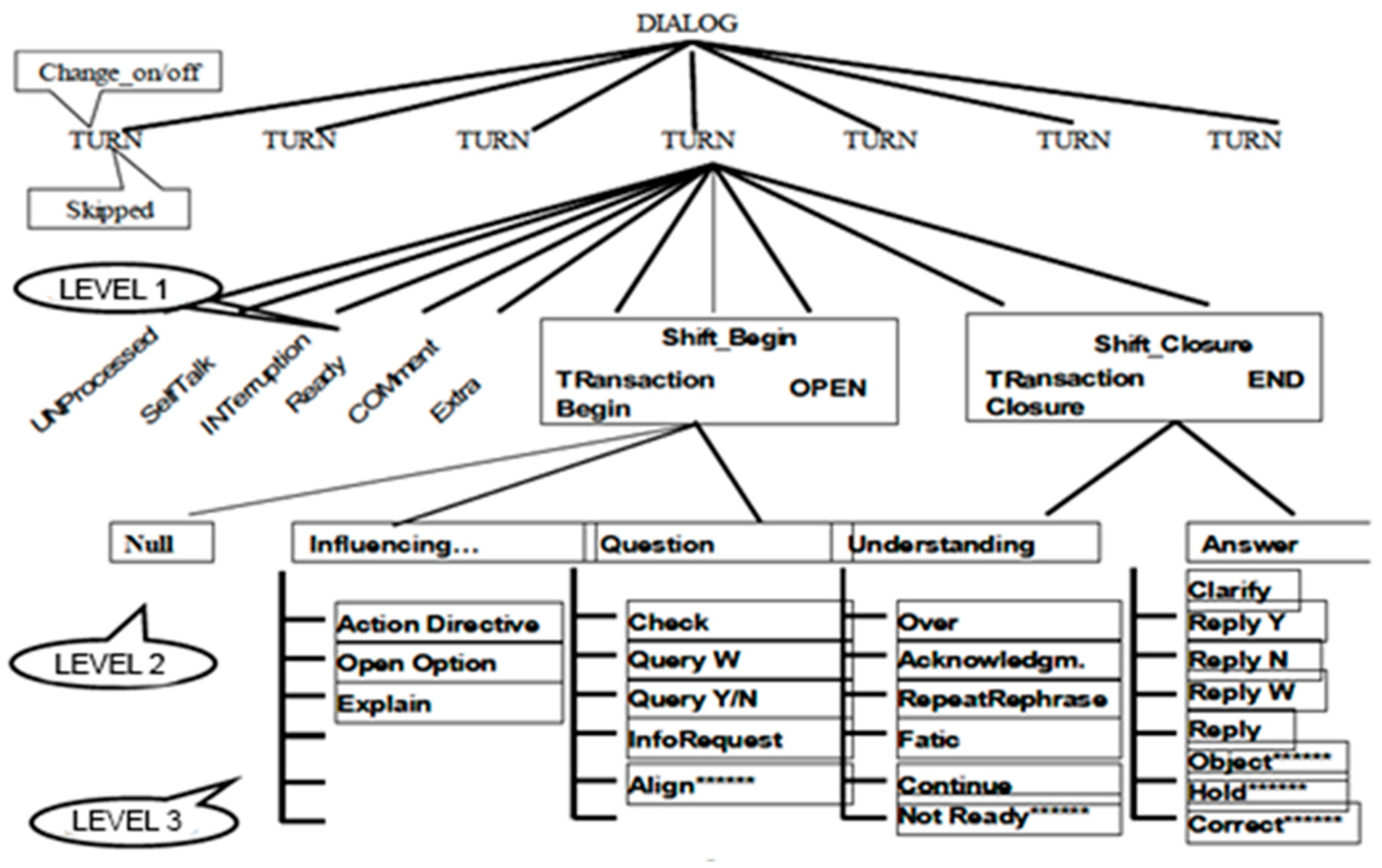

- (1)

- Null describes a move of alignment between the participants that serves to open the dialogical exchange.

- (2)

- Influencing provides participatory feedback to the action of the interlocutor in order to complete the task. This includes moves such as the Action Directive (in which the proposer instructs their interlocutor), the Open Options (in which one of the two participants in the communication exchange gives directions to continue the conversation), and the Explains (an explanation and direct description of what the subject of the exchange is).

- (3)

- Question requires communicative feedback relative to the interlocutor compared to the previous move. These include polar and non-polar questions (Query Y/N and Query Wh), requests for information (Info Request), confirmation requests (Check), and an alignment by the subjects who are interacting (Align).

- (4)

- Understanding underlines the reception of the message by the interlocutor via acknowledgment signals, anticipatory completion (Continue), a time take-up using repetition (Repeat_Rephrase), a phatic expression (Phatic), a manifestation of understanding and solution of the game (Over), and its misunderstanding (Not_Ready).

- (5)

- Answer realizes a communicative contribution from the requested interlocutor both explicitly and implicitly. As a result, there will be explicit answers to the questions previously asked (Reply Y/N; Reply Wh), clarifying answers to what has been said (Clarify), objections (Objects) or corrections (Correct), and answers that indicate doubts and uncertainties (Hold).

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

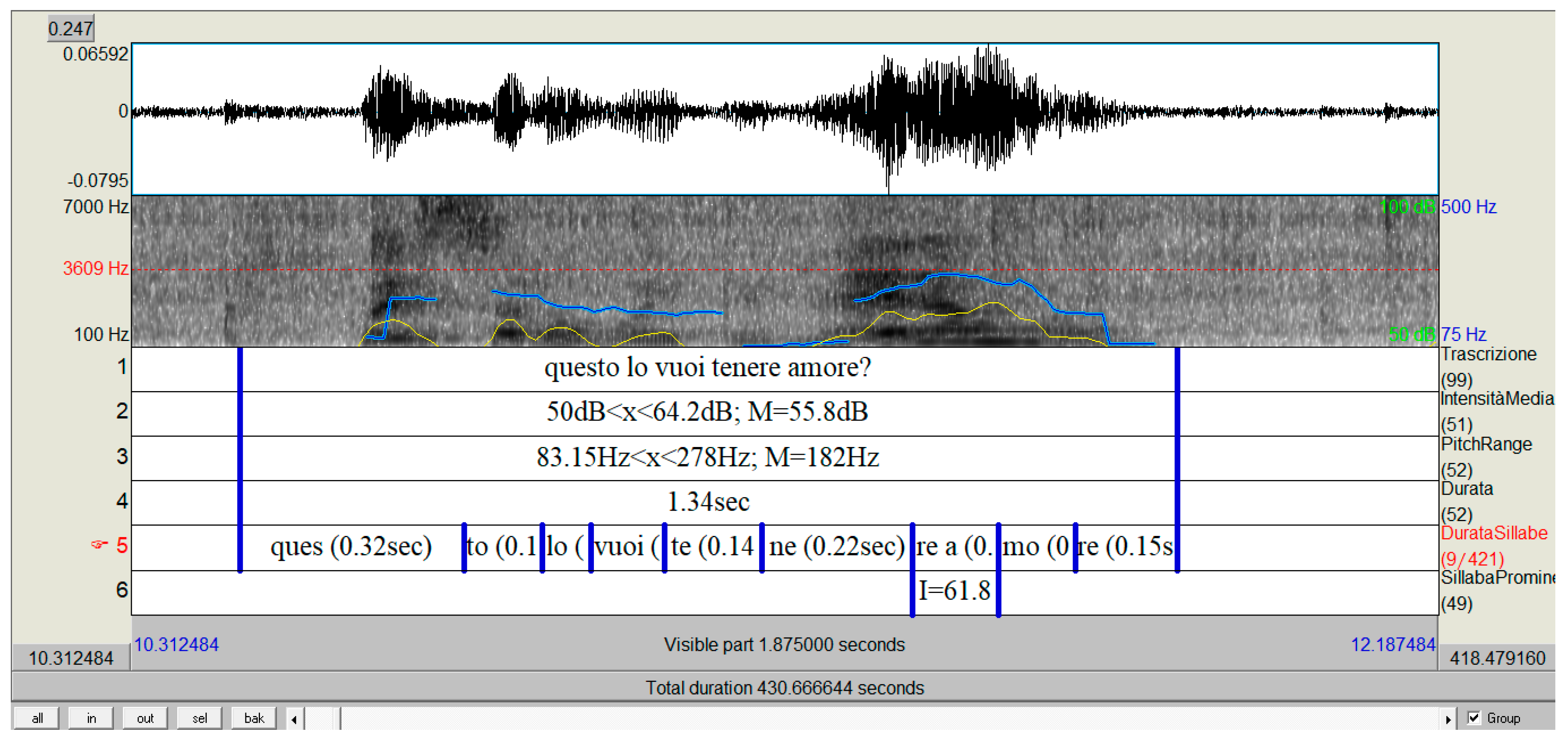

3.1. Speech Analysis

3.2. Behavior in the Communication Exchange (Code of the Evaluation of Shift Alternation)

3.3. Dialogical Moves (Pra.Ti.D.)

3.4. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kugiumutzakis, G.; Trevarthen, C. Neonatal Imitation. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 16, pp. 481–488. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, B.; Messinger, D.; Bahrick, L.E.; Margolis, A.; Buck, K.A.; Chen, A. A Systems View of Mother–Infant Face-to-Face Communication. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolis, A.E.; Lee, S.H.; Peterson, B.S.; Beebe, B. Profiles of infant communicative behavior. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 1594–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messinger, D.; Mahoor, M.; Chow, S.; Haltigan, J.D.; Cadavid, S.; Cohn, J.F. Early Emotional Communication: Novel Approaches to Interaction. In Social Emotions in Nature and Artifact: Emotions in Human and Human Computer Interaction; Gratch, J., Marsella, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 162–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rautakoski, P.; Ursin, P.A.; Carter, A.S.; Kaljonen, A.; Nylund, A.; Pihlaja, P. Communication skills predict social-emotional competencies. J. Commun. Disord. 2021, 9, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, B.; Kovack-Lesh, K.; McEchron, W. Infant directed speech and the development of speech perception: Enhancing development or an unintended consequence? Cognition 2013, 129, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.C.; Clayton, K.R.H.; Reynolds, G.D. Infant selective attention to native and non-native audiovisual speech. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.M.; Ratner, N.B.; Newman, R.S. Infant-directed speech (IDS) vowel clarity and child language outcomes. J. Child Lang. 2017, 4, 1140–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernald, A. Four-month-old infants prefer to listen to motherese. Infant Behav. Dev. 1985, 8, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C.J.; Gorman, E.; Hamby, D.W. Preference for infant-directed speech in preverbal young children. Cent. Early Lit. Learn. 2012, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Outters, V.; Schreiner, M.S.; Behne, T.; Mani, N. Maternal input and infants’ response to infant-directed speech. Infancy 2020, 25, 478–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Georges, C.; Chetouani, M.; Cassel, R.; Apicella, F.; Mahdhaoui, A.; Muratori, F.; Cohen, D. Motherese in interaction: At the cross-road of emotion and cognition? (A systematic review). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 78103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V.; Nagy, E. Fetal Behavioural Responses to Maternal Voice and Touch. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgács, B.; Parise, E.; Csibra, G.; Gergely, G.; Jacquey, L.; Gervain, J. Fourteen-month-old infants track the language comprehension of communicative partners. Dev. Sci. 2019, 22, e12751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Fyfield, R.; Baibazarova, E.; van Goozen, S.; Culling, J.F.; Hay, D.F. Parental speech at 6 months predicts joint attention at 12 months. Infancy 2013, 18 (Suppl. S1), E1–E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, M.; Carpenter, M.; Call, J.; Behne, T.; Moll, H. Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28, 675–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundy, P. A review of joint attention and social-cognitive brain systems in typical development and autism spectrum disorder. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 47, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, A.E.; Power, M. Influences of infants’ and mothers’ contingent vocal responsiveness on young infants’ vocal social bids in the Still Face Task. Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 69, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrace, H.S.; Bigelow, A.E.; Beebe, B. Intersubjectivity and the Emergence of Words. Front Psychol. 2022, 13, 693139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezia, M.; Messinger, D.S.; Thorp, D.; Mundy, P. The development of anticipatory smiling. Infancy 2004, 6, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrup, J.B.; Iverson, J.M. Multimodal coordination of vocal and gaze behavior in mother-infant dyads across the first year of life. Infancy 2020, 25, 952–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Aureli, T.; Coppola, G.; Ponzetti, S.; Lionetti, F.; Scialpi, V.; Fasolo, M. Verbal—Prosodic association when narrating early caregiving experiences during the adult attachment interview: Differences between secure and dismissing individuals. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2022, 24, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, E Statistical language learning: Computational, maturational, and linguistic constraints. Lang. Cogn. 2016, 8, 447–461. [CrossRef]

- Papoušek, M.; Papoušek, H.; Haekel, M. Didactic adjustments in fathers’ and mothers’ speech to their 3-month-old infants. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 1987, 16, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, A.; Kuhl, P.K. Acoustic determinants of infant preference for motherese speech. Infant Behav. Dev. 1987, 10, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnot, M.; Orbello, D.; Riccardo, L.; Sikka, S.; Ross, E. Acoustic analysis support subjective judgments of vocal emotion. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2003, 1000, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröer, L.; Çetin, D.; Vacaru, S.V.; Addabbo, M.; van Schaik, J.E.; Hunnius, S. Infants’ sensitivity to emotional expressions in actions: The contributions of parental expressivity and motor experience. Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 68, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Esparza, N.; García-Sierra, A.; Kuhl, P.K. Look Who’s Talking NOW! Parentese Speech, Social Context, and Language Development Across Time. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casillas, M.; Brown, P.; Levinson, S.C. Early Language Experience in a Tseltal Mayan Village. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 1819–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casillas, M.; Brown, P.; Levinson, S.C. Early language experience in a Papuan community. J. Child Lang. 2021, 48, 792–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuti, P.; Gnisci, A.; Marcone, R.; Senese, V.P. Simmetria nel gioco madre-bambino: Analisi sequenziale di scambi interattivi [Symmetry in the mother-child play: Sequential analysis of interactive exchanges]. DiPav 2001, 2, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gnisci, A.; Bakeman, R. L’osservazione e L’analisi Sequenziale Dell’Interazione [The Observation and the Sequential Analysis of the Interaction]; Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia e Diritto (LED): Milan, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Weighted Kappa: Nominal Scale Agreement Provision for Scaled Disagreement or Partial Credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 70, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeman, R.; Gottman, J.M. Observing Interaction: An Introduction to Sequential Analysis; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Castagneto, M. Il sistema di annotazione Pra.Ti.D tra gli altri sistemi di annotazione pragmatica. Le ragioni di un nuovo schema. In Annali del Dipartimento di Studi Letterari, Linguistici e Comparati-Sezione Linguistica; Silvestri, D., Manco, A., Eds.; Open Archives; Università “L’Orientale”: Napoli, Italy, 2012; pp. 105–148. ISSN 2281-6585. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt-Reed, M.M.; Long, H.L.; Bowman, D.D.; Bene, E.R.; Oller, D.K. The origin of language and relative roles of voice and gesture in early communication development. Infant Behav. Dev. 2021, 65, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leclère, C.; Viaux, S.; Avril, M.; Achard, C.; Chetouani, M.; Missonnier, S.; Cohen, D. Why synchrony matters during mother-child interactions: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, S.; Lange, T.; Hansen, G.F.; Væver, M.; Køppe, S. A longitudinal study of coordination in mother-infant vocal interaction from age 4 to 10 months. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, L.R.; Bornstein, M.H. Synchrony in mother-infant vocal interactions revealed through timed event sequences. Infant Behav. Dev. 2021, 64, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrup, J.B.; Iverson, J.M. The development of mother-infant coordination across the first year of life. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratier, M.; Devouche, E.; Guella, B.; Infanti, R.; Yilmaz, E.; Parlato-Oliveira, E. Early development of turn-taking in vocal interaction between mothers and infants. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räsänen, O.; Kakouros, S.; Soderstrom, M. Is infant-directed speech interesting because it is surprising?—Linking properties of IDS to statistical learning and attention at the prosodic level. Cognition 2018, 178, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, M.; Fogel, A. Interdyad differences in early mother-infant face-to-face communication: Real-time dynamics and developmental pathways. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 2257–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, E.; Dick, F. Language, gesture, and the developing brain. Dev. Psychobiol. 2002, 40, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.R.; Vigil, D.C.; Carlson, R. Frequency of Gesture Use and Language in Typically Developing Prelinguistic Children. Infant Behav. Dev. 2021, 62, 101527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gros-Louis, J. Infants’ prelinguistic communicative acts and maternal responses: Relations to linguistic development. First Lang. 2014, 34, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novack, M.A.; Brentari, D.; Goldin-Meadow, S.; Waxman, S. Sign language, like spoken language, promotes object categorization in young hearing infants. Cognition 2021, 215, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variabile | Months | M. | D.S. | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

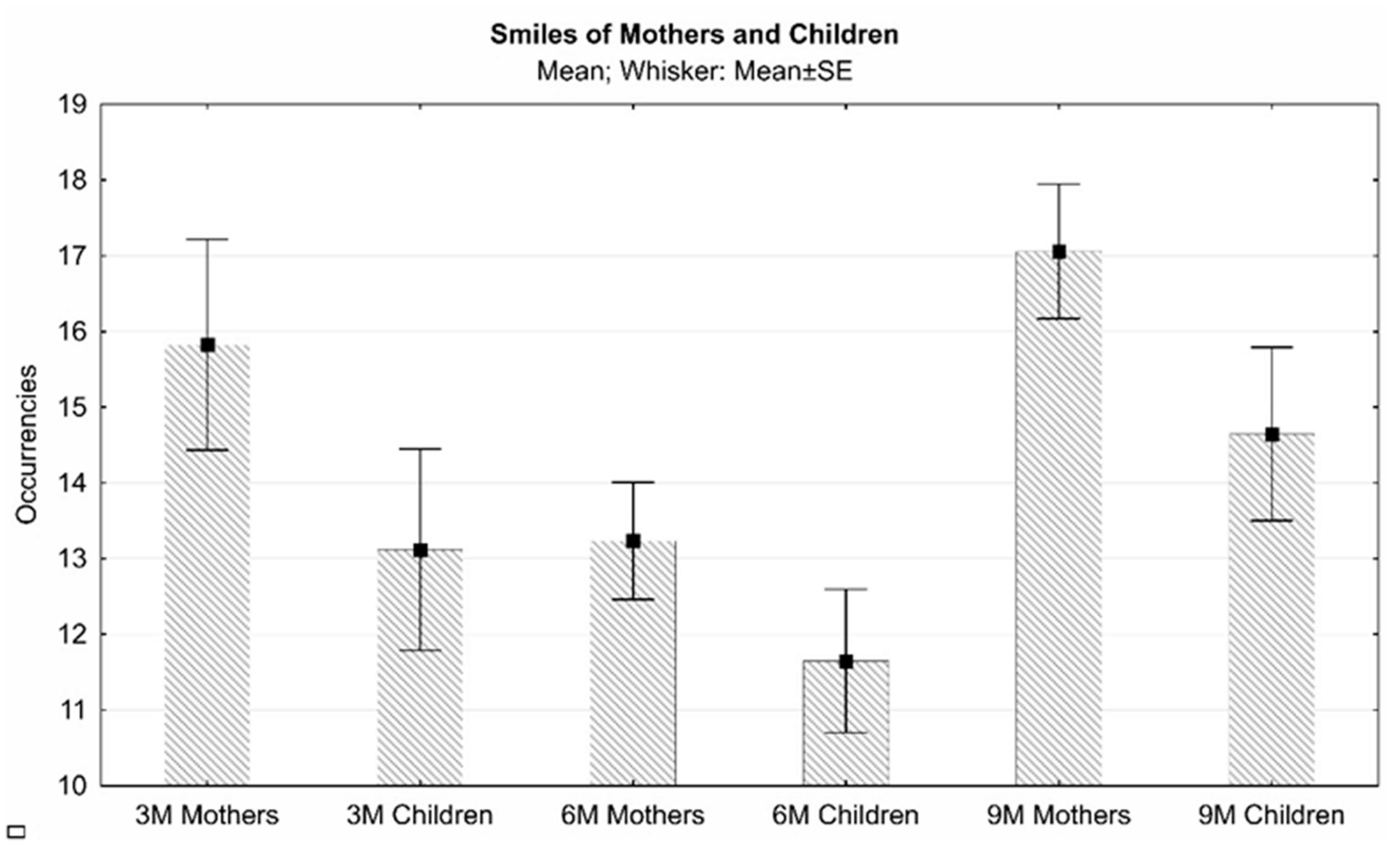

| Maternal Smile (occurrences) | 3 | 15.82 | 5.74 | 7–14 |

| 6 | 13.24 | 3.19 | 7–18 | |

| 9 | 17.06 | 3.67 | 10–23 | |

| Child Smile (occurrences) | 3 | 13.12 | 5.48 | 5–24 |

| 6 | 11.65 | 3.90 | 7–18 | |

| 9 | 14.65 | 4.72 | 6–23 | |

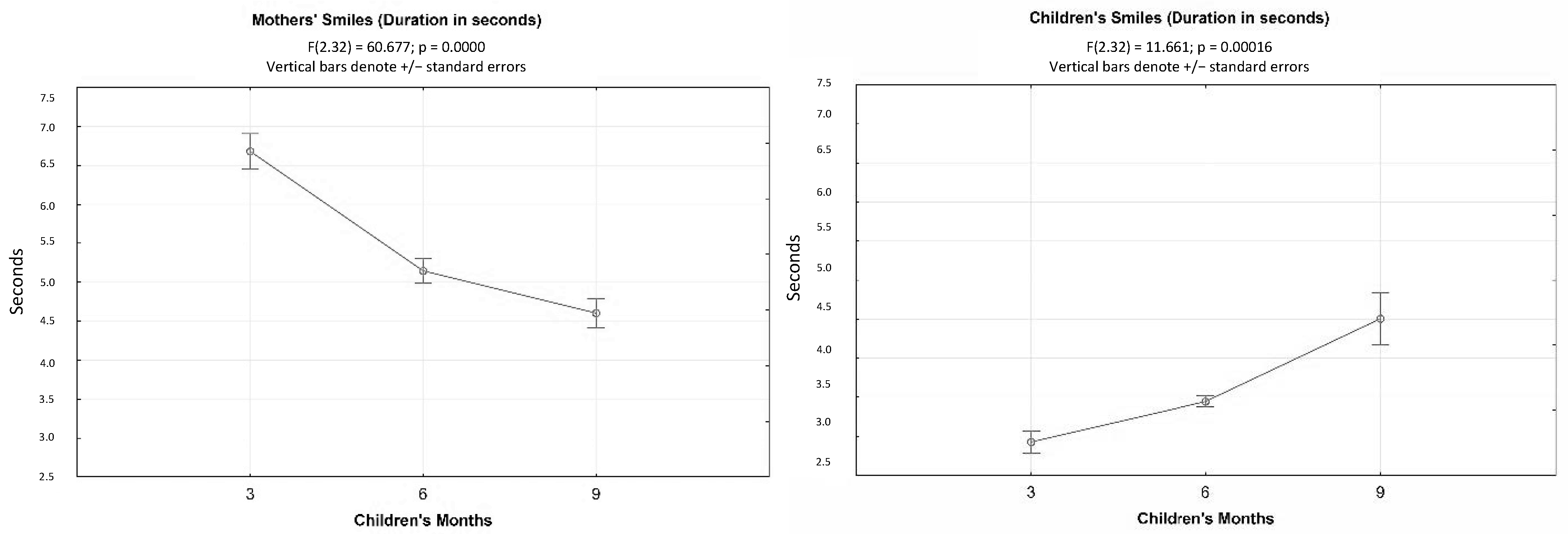

| Maternal smile (durations) | 3 | 6.68 | 0.93 | 5.50–8.40 |

| 6 | 5.15 | 0.67 | 4.60–6.78 | |

| 9 | 4.60 | 0.79 | 3.70–5.90 | |

| Child Smile (durations) | 3 | 2.93 | 0.59 | 2.30–4.30 |

| 6 | 3.45 | 0.30 | 3.00–3.87 | |

| 9 | 4.51 | 1.38 | 2.87–6.65 | |

| Contact (occurrences) | 3 | 7.59 | 5.05 | 1–19 |

| 6 | 6.77 | 2.28 | 3–10 | |

| 9 | 9.18 | 2.77 | 4–14 | |

| Look at the object (occurrences) | 3 | 5.53 | 2.70 | 1–11 |

| 6 | 4.88 | 2.62 | 1–9 | |

| 9 | 5.94 | 2.88 | 2–11 | |

| Unrequited smile (occurrences) | 3 | 2.24 | 2.49 | 0–8 |

| 6 | 1.59 | 2.50 | 0–8 | |

| 9 | 6.82 | 2.74 | 0–9 | |

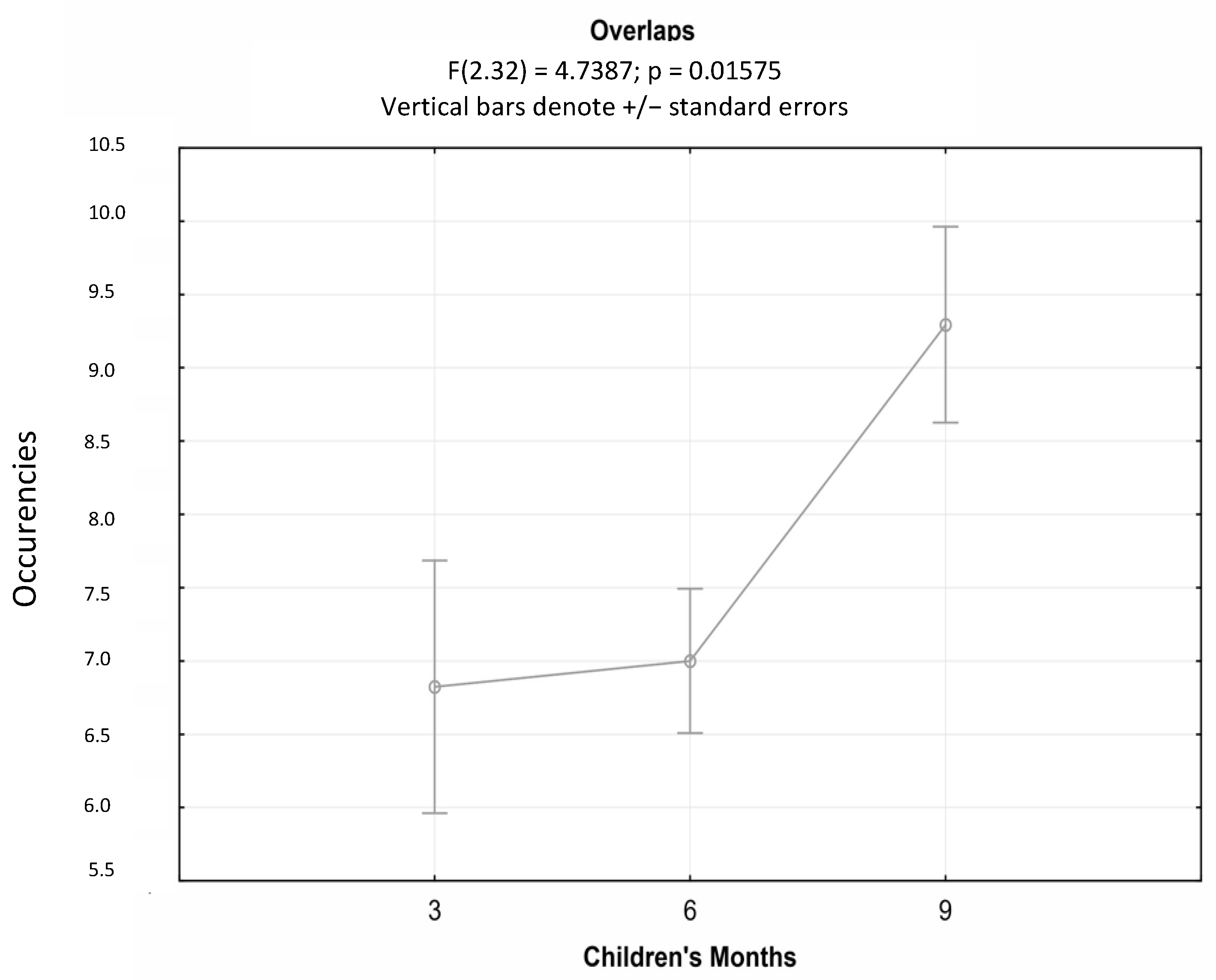

| Overlaps (occurrences) | 3 | 6.82 | 3.56 | 1–14 |

| 6 | 7.00 | 2.03 | 4–10 | |

| 9 | 9.24 | 2.76 | 2–14 |

| Variable | Month | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influencing | ||||

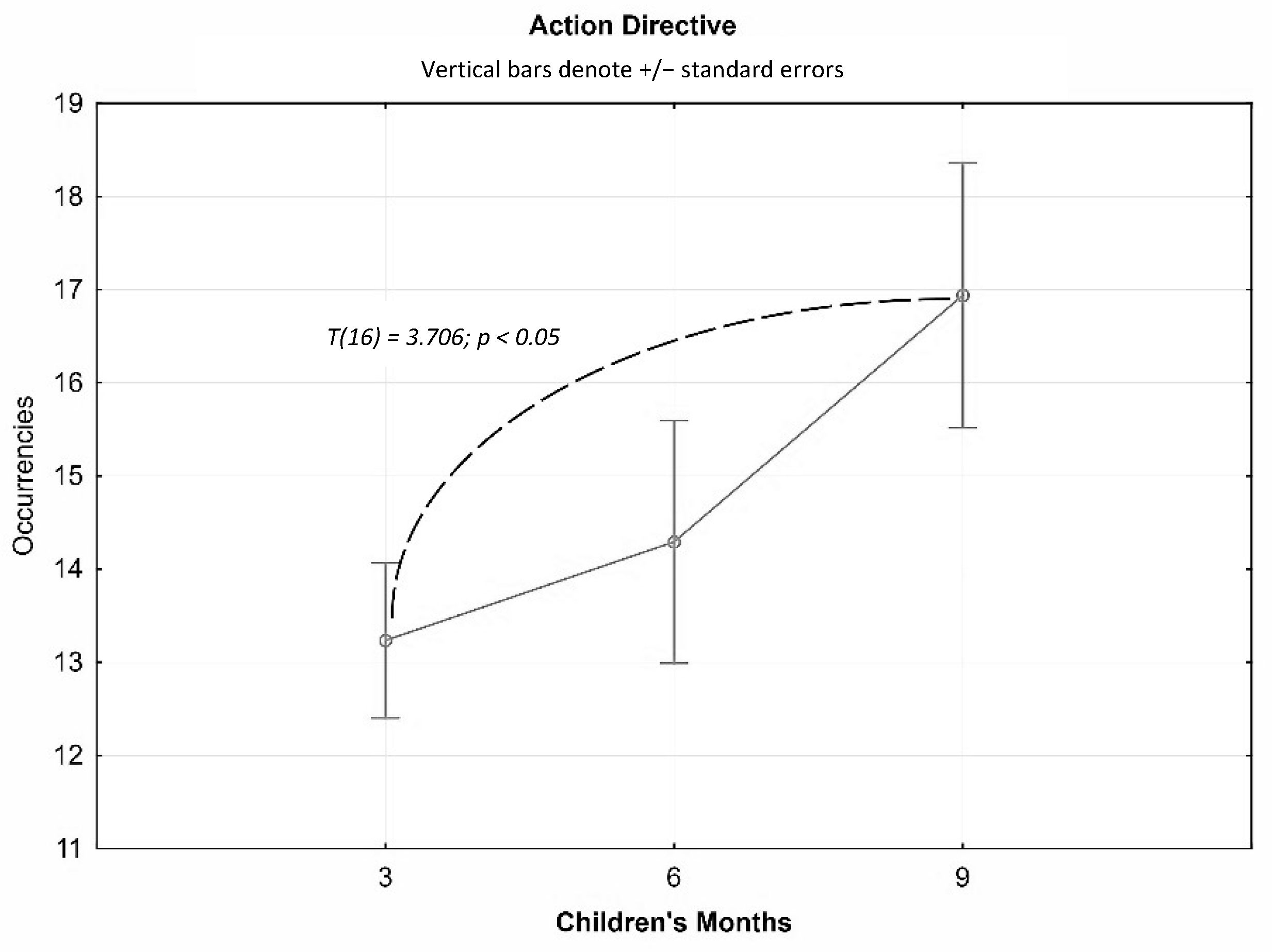

| Action Directive | 3 | 13.23 | 3.44 | 4–19 |

| 6 | 14.29 | 5.37 | 5–21 | |

| 9 | 16.94 | 5.87 | 7–25 | |

| Open Option | 3 | 11.76 | 7.13 | 1–22 |

| 6 | 10.47 | 6.62 | 0–23 | |

| 9 | 12.41 | 6.17 | 2–25 | |

| Explain | 3 | 9.24 | 6.48 | 0–21 |

| 6 | 9.12 | 4.73 | 1–20 | |

| 9 | 8.53 | 5.93 | 0–23 | |

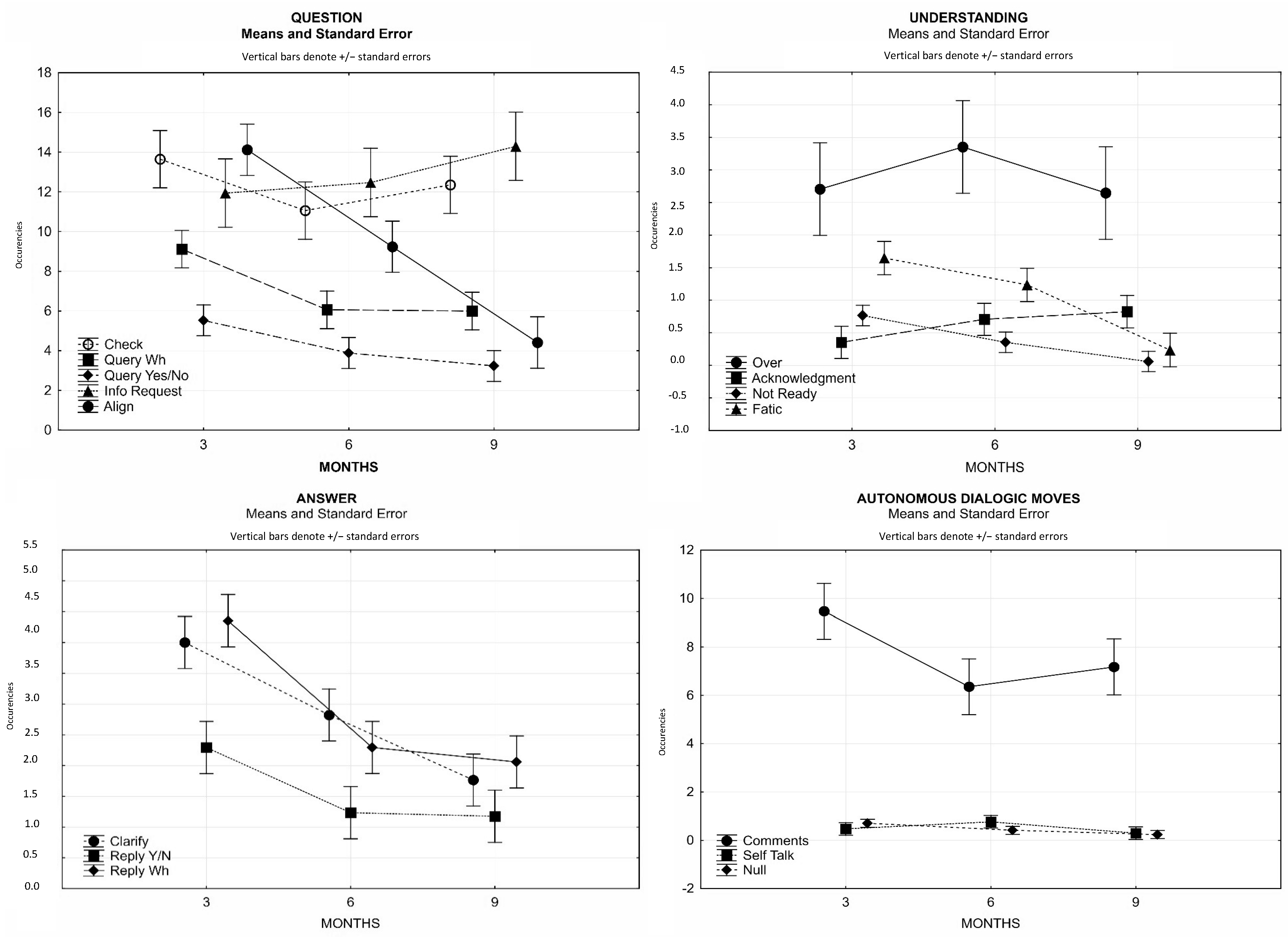

| Question | ||||

| Query Y/N | 3 | 5.53 | 2.90 | 0–11 |

| 6 | 3.88 | 2.52 | 1–9 | |

| 9 | 3.24 | 4.01 | 0–13 | |

| Query Wh | 3 | 9.12 | 3.20 | 5–15 |

| 6 | 6.06 | 3.07 | 1–13 | |

| 9 | 6.00 | 5.09 | 1–15 | |

| Info Request | 3 | 11.94 | 6.00 | 1–19 |

| 6 | 12.47 | 7.84 | 0–24 | |

| 9 | 14.29 | 7.29 | 1–25 | |

| Check | 3 | 13.65 | 6.04 | 3–22 |

| 6 | 11.06 | 4.72 | 4–18 | |

| 9 | 12.35 | 6.86 | 2–25 | |

| Align | 3 | 14.12 | 6.88 | 4–25 |

| 6 | 9.24 | 5.61 | 0–19 | |

| 9 | 4.41 | 2.50 | 0–9 | |

| Understanding | ||||

| Acknowledgment | 3 | 0.35 | 1.06 | 0–4 |

| 6 | 0.71 | 0.85 | 0–2 | |

| 9 | 0.83 | 1.13 | 0–3 | |

| Phatic | 3 | 1.65 | 0.86 | 0–3 |

| 6 | 1.24 | 1.56 | 0–5 | |

| 9 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0–1 | |

| Over | 3 | 2.71 | 2.23 | 0–8 |

| 6 | 3.35 | 3.10 | 0–9 | |

| 9 | 2.65 | 3.35 | 0–13 | |

| Not Ready | 3 | 0.76 | 0.90 | 0–3 |

| 6 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0–2 | |

| 9 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0–1 | |

| Answer | ||||

| Reply Y/N | 3 | 2.29 | 1.93 | 0–6 |

| 6 | 1.24 | 1.44 | 0–5 | |

| 9 | 1.18 | 1.85 | 0–7 | |

| Reply Wh | 3 | 4.35 | 1.84 | 1–8 |

| 6 | 2.29 | 1.10 | 0–5 | |

| 9 | 2.06 | 2.14 | 0–5 | |

| Clarify | 3 | 4.00 | 2.24 | 0–7 |

| 6 | 2.82 | 1.42 | 0–5 | |

| 9 | 1.76 | 1.44 | 0–5 | |

| Autonomous Moves | ||||

| Comments | 3 | 9.47 | 4.12 | 3–15 |

| 6 | 6.35 | 4.20 | 0–17 | |

| 9 | 7.18 | 5.79 | 0–21 | |

| Self Talk | 3 | 0.47 | 1.12 | 0–4 |

| 6 | 0.76 | 1.39 | 0–5 | |

| 9 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0–1 | |

| Null | 3 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0–3 |

| 6 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0–1 | |

| 9 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0–1 |

| (3 M) [6 M] {9 M} | OO | Ex | Ch | Q Wh | Q Y/N | IR | Al | Ov | Ac | Fa | Cl | R Y/N | R Wh | Co | Ho | Null |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | (0.50 *) | (0.49 *) | (−0.48 *) | |||||||||||||

| [0.52 *] | [0.51 *] | |||||||||||||||

| {0.65 **} | {0.66 **} | {0.65 **} | ||||||||||||||

| OO | (0.72 ***) | (0.74 ***) | (0.61 **) | (0.73 ***) | (0.61 **) | |||||||||||

| [0.62 **] | ||||||||||||||||

| {0.67 **} | {0.55 *} | |||||||||||||||

| Ex | (0.60 *) | (0.69 **) | (0.55 *) | (0.53 *) | (0.60 *) | |||||||||||

| [−0.57 *] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ch | (0.63 **) | (0.53 *) | (0.87 ***) | (0.45 *) | ||||||||||||

| [0.63 **] | [0.51 *] | |||||||||||||||

| {0.70 **} | ||||||||||||||||

| QWh | (0.78 ***) | (0.65 **) | (0.76 ***) | (0.62 **) | (0.62 **) | |||||||||||

| [0.73 ***] | ||||||||||||||||

| {0.56 *} | {−0.60 *} | {0.60 *} | {0.64 **} | |||||||||||||

| QY/N | (0.51 *) | (0.63 **) | (0.78 ***) | |||||||||||||

| [0.59 *] | ||||||||||||||||

| {0.68 **} | ||||||||||||||||

| IR | (0.76 ***) | (0.51 *) | (0.65 **) | |||||||||||||

| [0.63 **] | [−0.54 *] | [0.68 **] | [0.50 *] | |||||||||||||

| {0.49 *} | ||||||||||||||||

| Al | (0.52 *) | (−0.53 *) | (0.71 **) | |||||||||||||

| {0.59 *} | ||||||||||||||||

| Ov | ||||||||||||||||

| {0.63 **} | ||||||||||||||||

| Ac | (0.56 *) | (0.62 **) | ||||||||||||||

| [−0.51 *] | ||||||||||||||||

| Ph | (0.52 *) | |||||||||||||||

| RY/N | ||||||||||||||||

| {0.52 *} |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tenuta, F.; Marcone, R.; Graziano, E.; Craig, F.; Romito, L.; Costabile, A. A Preliminary Longitudinal Study on Infant-Directed Speech (IDS) Components in the First Year of Life. Children 2023, 10, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030413

Tenuta F, Marcone R, Graziano E, Craig F, Romito L, Costabile A. A Preliminary Longitudinal Study on Infant-Directed Speech (IDS) Components in the First Year of Life. Children. 2023; 10(3):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030413

Chicago/Turabian StyleTenuta, Flaviana, Roberto Marcone, Elvira Graziano, Francesco Craig, Luciano Romito, and Angela Costabile. 2023. "A Preliminary Longitudinal Study on Infant-Directed Speech (IDS) Components in the First Year of Life" Children 10, no. 3: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030413

APA StyleTenuta, F., Marcone, R., Graziano, E., Craig, F., Romito, L., & Costabile, A. (2023). A Preliminary Longitudinal Study on Infant-Directed Speech (IDS) Components in the First Year of Life. Children, 10(3), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030413