Toxic Stress as a Potential Factor Inducing Negative Emotions in Parents of Newborns and Infants with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- What are the levels of anxiety, depression and aggression in mothers and fathers of children with cyanotic heart disease depending on the stage of the patient’s cardiac surgery treatment?

- What is the level of perceived stress in mothers and fathers of children with cyanotic heart disease depending on the stage of the patient’s cardiac surgery treatment?

- What is the relationship between the negative emotions studied and the level of stress, and selected sociodemographic variables, the stage of treatment and the time of diagnosis of the defect in the child?

2.2. Sample, Setting & Data Collection

2.3. Participants and Public Involvement

2.4. Description of Research Tools

- -

- Self-designed questionnaire—regarding sociodemographic data: respondents’ age and gender, education, place of residence, child’s age, type of disease and its stage of treatment (e.g.: before cardiac surgery, after cardiac surgery).

- -

- The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), developed by Zigmond and Snaith [17], in the Polish adaptation by Majkowicz et al. [18]. It consists of three subscales assessing the occurrence of anxiety, depression and aggression/irritability among psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients who require assessment of their emotional state. Aggression examined with this tool should be understood as a state of emotional irritation or a feeling of aggression. The subscales can be interpreted separately or in total. The HADS scale was used due to its advantages, such as general availability, ease of use, possibility of use by nurses and doctors, and no need to involve psychologists, which significantly reduces the costs of using it. The analysis of the respondents’ answers was made in accordance with the instructions of the authors of the scale and the authors of the adaptation [17,18]: (i) no disorders: 0–7 pts.—depression/anxiety subscale, 0–2 pts.—aggression/irritability subscale; (ii) borderline states: 8–10 pts.—depression/anxiety subscale, 3 pts.—aggression subscale; (iii) observed disorders: 11–21 pts.—depression/anxiety subscale, 4–6 pts.—aggression subscale. For the purposes of the current study, each subscale was analyzed separately as well as in total.

- -

- The Perceived Stress Scale—10 (PSS-10), developed by Cohen et al. [19], in the Polish adaptation by Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik [20]. A screening scale is used to identify people requiring psychological support. The analysis of respondents’ answers and the calculation of results were consistent with the key developed by the authors of the tool and the authors of the adaptation [19,20]. Therefore, a result of 1 to 4 sten was considered as low, 5 to 6 sten was considered as average, and 7 to 10 sten was considered as high. A high score on the PSS scale is an indicator of the assessment of one’s own life situation as stressful and excessively burdensome.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Group

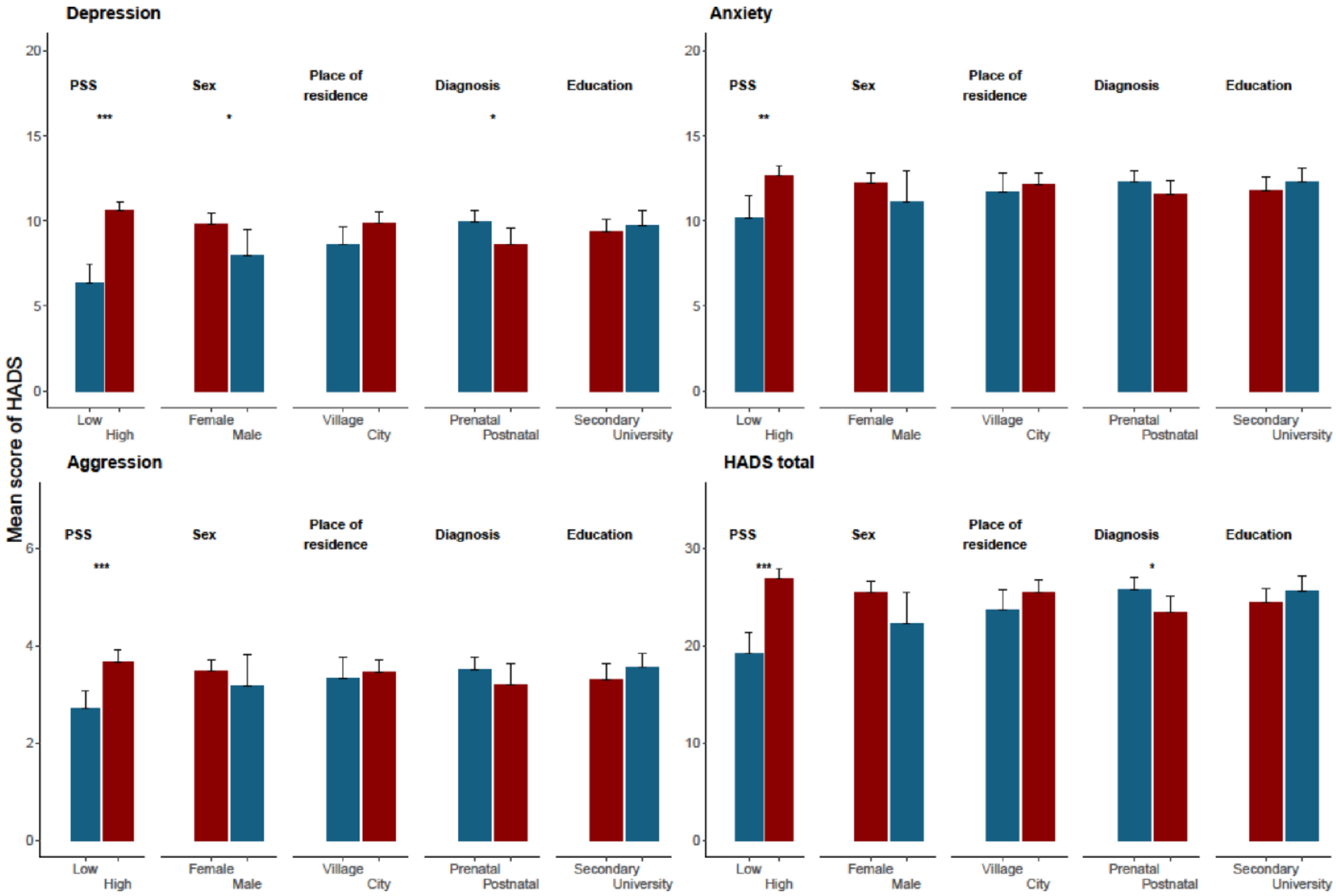

3.2. Anxiety, Depression and Aggression/Irritability Levels vs. Parental Stress Level and Selected Socio-Demographic and Clinical Variables

3.3. Probability of the Incidence of Anxiety, Depression and Aggression/Irritability Depending on Parents’ Stress Levels

3.4. The Assessment of the Relationship between PSS-10 Score and HADS Domains as Continuous Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Search Strategy and Selection

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rozkrut, D. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2022; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; p. 221. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; He, J.; Shao, X. Incidence and mortality trend of congenital heart disease at the global, regional, and national level, 1990–2017. Medicine 2020, 99, e20593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białkowski, J. Pediatric cardiology in Poland in 2019. Kardiol. Pol. 2020, 78, 950–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Ahn, J.A. Experiences of mothers facing the prognosis of their children with complex congenital heart disease. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalir, Z.; Heydari, A.; Kareshki, H.; Manzari, Z.S. Coping with caregiving stress in families of children with congenital heart disease: A qualitative study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2020, 8, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayeri, N.D.; Roddehghan, Z.; Mahmoodi, F.; Mahmoodi, P. Being parent of a child with congenital heart disease, what does it mean? A qualitative research. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.D.; Kazazian, V.; Ford, M.K.; Marii, D.; Millera, S.P.; Chau, V.; Seed, M.; Ly, L.G.; Williams, T.S.; Sananes, R. The association between parent stress, coping and mental health, and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants with congenital heart disease. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2021, 35, 948–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, F.; Sertcelik, T.; Sapmaz, S.Y.; Eser, E.; Coskun, S. Responses of mothers of children with CHD: Quality of life, anxiety and depression, parental attitudes, family functionality. Cardiol. Young 2017, 27, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaitis, G.A.; Meentken, M.G.; Utens, E.M.W.J. Mental health problems in parents of children with congenital heart disease. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsden, M.R.; Smith, D.M.; Twigg, E.; Guerrero, R.; Wittkowski, A. Children with single ventricle congenital heart defects: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the lived parent experience. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2020, 59, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, E.; Karpyn, A.; Demianczyk, A.C.; Ryan, J.; Delaplane, E.A.; Neely, T. Mothers and fathers experience stress of congenital heart disease differently: Recommendations for pediatric critical care. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 19, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, M.; Cohen, L.L.; Robbertz, A.S. Illness-related parenting stress and maladjustment in congenital heart disease: Mindfulness as a moderator. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golfenshtein, N.; Hanlon, A.L.; Deatrick, J.A.; Medoff-Cooper, B. Parenting stress trajectories during infancy in infants with congenital heart disease: Comparison of single-ventricle and biventricular heart physiology. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2019, 14, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, E.; Chang, Y.S. From surviving to thriving—Parental experiences of hospitalised infants with congenital heart disease undergoing cardiac surgery: A qualitative synthesis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2020, 51, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomi, M.; Pfammatter, J.P.; Spichiger, E. Parental emotional and hands-on work-experiences of parents with a newborn undergoing congenital heart surgery: A qualitative study. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 24, e12269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkowicz, M. Praktyczna ocena efektywności opieki paliatywnej—Wybrane techniki badawcze. In Ocena Jakości Opieki Paliatywnej Teorii i Praktyce; de Walden-Gałuszko, K., Majkowicz, M., Eds.; Akademia Medyczna Gdańsk, Zakład Medycyny Paliatywnej: Gdańsk, Poland, 2000; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juczyński, Z.; Ogińska-Bulik, N. Narzędzia Pomiaru Stresu i Radzenia Sobie ze Stresem; Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2009; pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Roscigno, C.I.; Hanson, C.C.; Swanson, K.M. Families of children with congenital heart disease: A literature review. Heart Lung 2015, 44, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.A.; De Waard, I.E.; Tooten, A.; Hoffenkamp, H.N.; Vingerhoets, A.J.; van Bakel, H.J. From the father’s point of view: How father’s representations of the infant impact on father-infant interaction and infant development. Early Hum. Dev. 2014, 90, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaudo, J.; Lawler, J.M.; Jester, J.M.; Riggs, J.; Erickson, N.L.; Stacks, A.M.; Brophy-Herb, H.; Muzik, M.; Rosenblum, K.L. Maternal history of adverse experiences and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms impact toddlers’ early socioemotional wellbeing: The benefits of infant mental health-home visiting. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 792989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutan, R.; Al-Saidi, N.A.; Latiff, Z.A.; Ibrahim, H.M. Coping strategies among parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Health 2017, 9, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharma, R.; Shyam, R.; Grover, S. Coping strategies used by parents of children diagnosed with cancer. Indian J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 34, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepuch, G.; Wojnar-Gruszka, K.; Gdańska, K. Emotional control versus anxiety, aggression, and depressive disorders in parents of children with malignant diseases. Psychoonkologia 2014, 18, 35–41. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, H.; Gebreyohannis, G.T.; Cherie, A. Depression and associated factors among parents of children diagnosed with cancer at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogman, M.; Garfield, C.F. Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: The role of pediatricians. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.F.; Karpyn, A.; Christofferson, J.; Neely, T.; McWhorter, L.G.; Demianczyk, A.C.; Mslis, R.J.; Hafer, J.; Kazak, A.E.; Sood, E. Fathers of children with congenital heart disease: Sources of stress and opportunities for intervention. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 21, e1002–e1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, A.K.; Prabhakaran, A.; Patel, P.; Ganjiwale, J.D.; Nimbalkar, S.M. Social, psychological and financial burden on caregivers of children with chronic illness: A cross-sectional study. Indian J. Pediatr. 2015, 82, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainberg, L.D.; Vardi, A.; Jacoby, R. The experiences of parents of children undergoing surgery for congenital heart defects: A holistic model of care. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf-King, S.E.; Anger, A.; Arnold, E.A.; Weiss, S.J.; Teitel, D. Mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects: A systematic review. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Składzień, T.; Wiśniowski, Z.; Jaworska, I.; Wójcik, E.; Mroczek, T.; Skalski, J.H. Anxiety, depressiveness and irritability in parentsof children treated surgically for congenital heart defects. Pol. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. Kardiochirurgia Torakochirurgia Polska 2011, 8, 479–482. [Google Scholar]

- Lisanti, A.J.; Kumar, A.; Quinn, R.; Chittams, J.L.; Medoff-Cooper, B.; Demianczyk, A.C. Role alteration predicts anxiety and depressive symptoms in parents of infants with congenital heart disease: A pilot study. Cardiol. Young 2021, 31, 1842–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, H.S.; Pituch, K.; Uzark, K.; Bhat, P.; Fifer, C.; Silveira, M.; Yu, S.; Welch, S.; Donohue, J.; Lowery, R.; et al. A randomised trial of early palliative care for maternal stress in infants prenatally diagnosed with single-ventricle heart disease. Cardiol. Young 2018, 28, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuben, J.D.; Shaw, D.S.; Brennan, L.; Dishion, T.J.; Wilson, M.N. A family-based intervention for improving children’s emotional problems through effects on maternal depressive symptoms. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 83, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisanti, A.J.; Allen, L.R.; Kelly, L.; Medoff-Cooper, B. Maternal stress and anxiety in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Am. J. Crit. Care 2017, 26, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golfenshtein, N.; Hanlon, A.L.; Deatrick, J.A.; Medoff-Cooper, B. Parenting stress in parents of infants with congenital heart disease and parents of healthy infants: The first year of life. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2017, 40, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kapse, K.; Jacobs, M.; Niforatos-Andescavage, N.; Donofrio, M.T.; Krishnan, A.; Vezina, G.; Wessel, D.; Plessis, A.D.; Limperopoulos, C. Association of maternal psychological distress with in utero brain development in fetuses with congenital heart disease. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e195316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, A.J.; Golfenshtein, N.; Medoff-Cooper, B. The pediatric cardiac intensive care unit parental stress model: Refinement using directed content analysis. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 40, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, S.; Andonian, C.; Beckmann, J.; Ewert, P.; Freilinger, S.; Nagdyman, N.; Kaemmerer, H.; Oberhoffer, R.; Pieper, L.; Neidenbach, R.C. Current research status on the psychological situation of parents of children with congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurr, S.; Danford, C.A.; Roberts, K.J.; Sheppard-LeMoine, D.; Machado Silva-Rodrigues, F.; Darezzo Rodrigues Nunes, M.; Darmofal, L.; Ersig, A.L.; Foster, M.; Giambra, B.; et al. Fathers’ experiences of caring for a child with a chronic illness: A systematic review. Children 2023, 10, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | female | 132 (85.71) |

| male | 22 (14.29) | |

| Age | ≤29 | 51 (33.12) |

| 30–34 | 53 (34.42) | |

| ≥35 | 50 (32.47) | |

| Place of residence | >500,000 | 26 (16.88) |

| 200–500,000 | 30 (19.48) | |

| 100–200,000 | 35 (22.73) | |

| <100,000 | 28 (18.18) | |

| village | 35 (22.73) | |

| Education | elementary | 2 (1.30) |

| vocational | 18 (11.69) | |

| secondary | 54 (35.06) | |

| high | 80 (51.95) | |

| Time of disease diagnosis: | prenatal | 111 (72.08) |

| postnatal | 43 (27.92) | |

| Type of disease | TOF | 42 (27.27) |

| TGA | 23 (14.94) | |

| HLHS | 39 (25.32) | |

| TA | 12 (7.79) | |

| TAC | 14 (9.09) | |

| PA | 12 (7.79) | |

| TAPVR | 10 (6.49) | |

| other cyanotic defects | 2 (1.30) | |

| Defect correction | complete | 24 (15.58) |

| incomplete | 82 (53.25) | |

| none | 48 (31.17) | |

| HADS Depression—categories | no disorder | 37 (24.03) |

| borderline | 53 (34.42) | |

| disorder | 64 (41.56) | |

| HADS Anxiety—categories | no disorder | 12 (7.79) |

| borderline | 37 (24.03) | |

| disorder | 105 (68.18) | |

| HADS Aggression/Irritability—categories | ≤3 | 80 (51.95) |

| ≥4 | 74 (48.05) | |

| HADS total | no disorder | 14 (9.09) |

| borderline | 38 (24.68) | |

| disorder | 102 (66.23) | |

| PSS-10 catergories | low | 3 (1.95) |

| average | 34 (22.08) | |

| high | 117 (75.97) |

| Variable | Categories | Depression | Anxiety | Aggression/ Irritability | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None + Borderline | Disorder | p | None + Borderline | Disorder | p | ≤3 pkt | ≥4 pkt | p | None + Borderline | Disorder | p | ||

| Gender | female | 74 (56.06) | 58 (43.94) | 0.217 | 39 (29.55) | 93 (70.45) | 0.216 | 67 (50.76) | 65 (49.24) | 0.621 | 42 (31.82) | 90 (68.18) | 0.313 |

| male | 16 (72.73) | 6 (27.27) | 10 (45.45) | 12 (54.55) | 13 (59.09) | 9 (40.91) | 10 (45.45) | 12 (54.55) | |||||

| Place of residence | village | 26 (74.29) | 9 (25.71) | 0.049 | 12 (34.29) | 23 (65.71) | 0.881 | 16 (45.71) | 19 (54.29) | 0.517 | 17 (48.57) | 18 (51.43) | 0.057 |

| city | 64 (53.78) | 55 (46.22) | 37 (31.09) | 82 (68.91) | 64 (53.78) | 55 (46.22) | 35 (29.41) | 84 (70.59) | |||||

| Education | other | 46 (62.16) | 28 (37.84) | 0.461 | 25 (33.78) | 49 (66.22) | 0.741 | 43 (58.11) | 31 (41.89) | 0.190 | 26 (35.14) | 48 (64.86) | 0.861 |

| higher | 44 (55.00) | 36 (45.00) | 24 (30.00) | 56 (70.00) | 37 (46.25) | 43 (53.75) | 26 (32.50) | 54 (67.50) | |||||

| Time of diagnosis | prenatal | 60 (54.05) | 51 (45.95) | 0.111 | 35 (31.53) | 76 (68.47) | 1.000 | 58 (52.25) | 53 (47.75) | 1.000 | 32 (28.83) | 79 (71.17) | 0.059 |

| postnatal | 30 (69.77) | 13 (30.23) | 14 (32.56) | 29 (67.44) | 22 (51.16) | 21 (48.84) | 20 (46.51) | 23 (53.49) | |||||

| Heart defect correction | complete | 16 (66.67) | 8 (33.33) | 0.268 | 8 (33.33) | 16 (66.67) | 0.695 | 14 (58.33) | 10 (41.67) | 0.786 | 10 (41.67) | 14 (58.33) | 0.152 |

| incomplete | 43 (52.44) | 39 (47.56) | 28 (34.15) | 54 (65.85) | 42 (51.22) | 40 (48.78) | 22 (26.83) | 60 (73.17) | |||||

| none | 31 (64.58) | 17 (35.42) | 13 (27.08) | 35 (72.92) | 24 (50.00) | 24 (50.00) | 20 (41.67) | 28 (58.33) | |||||

| PSS-10 categories | Low + average | 32 (86.49) | 5 (13.51) | <0.001 | 19 (51.35) | 18 (48.65) | 0.006 | 30 (81.08) | 7 (18.92) | <0.001 | 27 (72.97) | 10 (27.03) | <0.001 |

| high | 58 (49.57) | 59 (50.43) | 30 (25.64) | 87 (74.36) | 50 (42.74) | 67 (57.26) | 25 (21.37) | 92 (78.63) | |||||

| Parents’ age | ≤29 | 27 (52.94) | 24 (47.06) | 0.530 | 15 (29.41) | 36 (70.59) | 0.737 | 18 (35.29) | 33 (64.71) | 0.013 | 15 (29.41) | 36 (70.59) | 0.668 |

| 30–34 | 31 (58.49) | 22 (41.51) | 19 (35.85) | 34 (64.15) | 33 (62.26) | 20 (37.74) | 20 (37.74) | 33 (62.26) | |||||

| 3 ≥ 35 | 32 (64.00) | 18 (36.00) | 15 (30.00) | 35 (70.00) | 29 (58.00) | 21 (42.00) | 17 (34.00) | 33 (66.00) | |||||

| Depression | Anxiety | Aggression/Irritability | Total HADS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| PSS | low/ medium | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| high | 6.91 (2.42; 19.73) * | 7.09 (2.42; 20.77) * | 3.00 (1.37; 6.57) * | 3.12 (1.40; 6.96) * | 5.40 (2.15; 13.55) * | 5.22 (2.06; 13.21) * | 12.02 (4.74; 30.45) * | 13.75 (5.09; 37.14) * | |

| Gender | female | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| male | 0.39 (0.13; 1.19) | 0.39 (0.13; 1.19) | 0.50 (0.19; 1.33) | 0.50 (0.19; 1.33) | 0.97 (0.35; 2.65) | 0.96 (0.35; 2.65) | 0.42 (0.13; 1.30) | 0.41 (0.13; 1.32) | |

| Age | ≤29 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 30–34 | 1.05 (0.44; 2.50) | 1.05 (0.44; 2.53) | 0.90 (0.38; 2.14) | 0.96 (0.40; 2.33) | 0.35 (0.15; 0.82) * | 0.36 (0.15; 0.86) * | 0.92 (0.34; 2.44) | 0.87 (0.32; 2.39) | |

| ≥35 | 0.76 (0.31; 1.83) | 0.78 (0.32; 1.90) | 1.22 (0.49; 3.00) | 1.23 (0.49; 3.03) | 0.45 (0.19; 1.06) | 0.46 (0.19; 1.09) | 1.08 (0.40; 2.97) | 1.14 (0.41; 3.19) | |

| Place of residence | other | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| city | 2.81 (1.14; 6.94) * | 2.81 (1.13; 7.01) * | 1.14 (0.49; 2.65) | 1.19 (0.51; 2.79) | 0.62 (0.27; 1.46) | 0.62 (0.27; 1.46) | 2.67 (1.07; 6.64) * | 2.57 (1.00; 6.55) * | |

| Time of diagnosis | prenatal | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| postnatal | 0.44 (0.19; 0.99) * | 0.48 (0.21; 1.13) | 0.88 (0.40; 1.94) | 0.81 (0.36; 1.85) | 0.95 (0.44; 2.07) | 1.03 (0.46; 2.29) | 0.33 (0.14; 0.81) * | 0.36 (0.14; 0.90) * | |

| Parents’ education | other | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) |

| higher | - | 1.05 (0.50; 2.19) | - | 0.99 (0.48; 2.06) | - | 1.36 (0.67; 2.76) | - | 0.72 (0.31; 1.68) | |

| Heart defect correction | complete | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) | - | 1 (ref.) |

| incomplete | - | 1.84 (0.64; 5.27) | - | 0.97 (0.35; 2.68) | - | 1.43 (0.53; 3.90) | - | 2.06 (0.66; 6.46) | |

| none | - | 1.30 (0.41; 4.06) | - | 1.49 (0.49; 4.58) | - | 1.37 (0.47; 4.02) | - | 1.24 (0.37; 4.13) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cepuch, G.; Kruszecka-Krówka, A.; Lalik, A.; Micek, A. Toxic Stress as a Potential Factor Inducing Negative Emotions in Parents of Newborns and Infants with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. Children 2023, 10, 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121893

Cepuch G, Kruszecka-Krówka A, Lalik A, Micek A. Toxic Stress as a Potential Factor Inducing Negative Emotions in Parents of Newborns and Infants with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. Children. 2023; 10(12):1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121893

Chicago/Turabian StyleCepuch, Grażyna, Agnieszka Kruszecka-Krówka, Anna Lalik, and Agnieszka Micek. 2023. "Toxic Stress as a Potential Factor Inducing Negative Emotions in Parents of Newborns and Infants with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease" Children 10, no. 12: 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121893

APA StyleCepuch, G., Kruszecka-Krówka, A., Lalik, A., & Micek, A. (2023). Toxic Stress as a Potential Factor Inducing Negative Emotions in Parents of Newborns and Infants with Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease. Children, 10(12), 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121893