Feasibility of Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) as a Framework for Aquatic Activities: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aquatic Activities for Children with Developmental Delay

1.2. Possible Way Forward

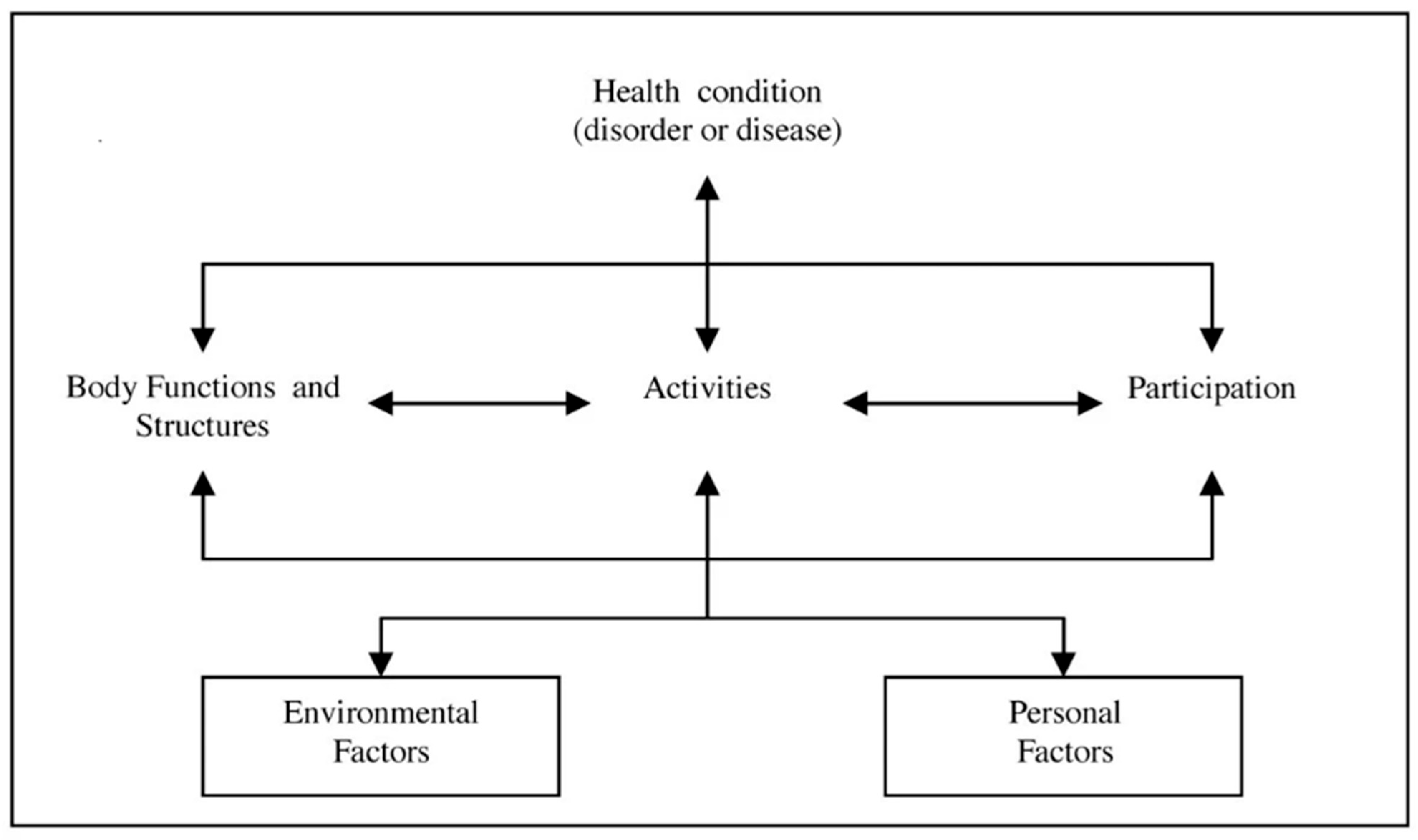

1.3. Background Rational for Using the ICF as a Unifying Framework and Language

1.4. What Is Known about the Extent to Which Linking Rules Are Used in Studies of AA for Children?

1.5. The Main Aim of This Study

- (A)

- Assessing the feasibility of linking—To examine whether the goals found to be positive in the selected articles can be linked to the language of the ICF-CY.

- (B)

- Reviewing the articles—To examine whether it is possible to review the results of the relevant articles with the unifying language of the ICF-CY framework.

2. Materials and Methods

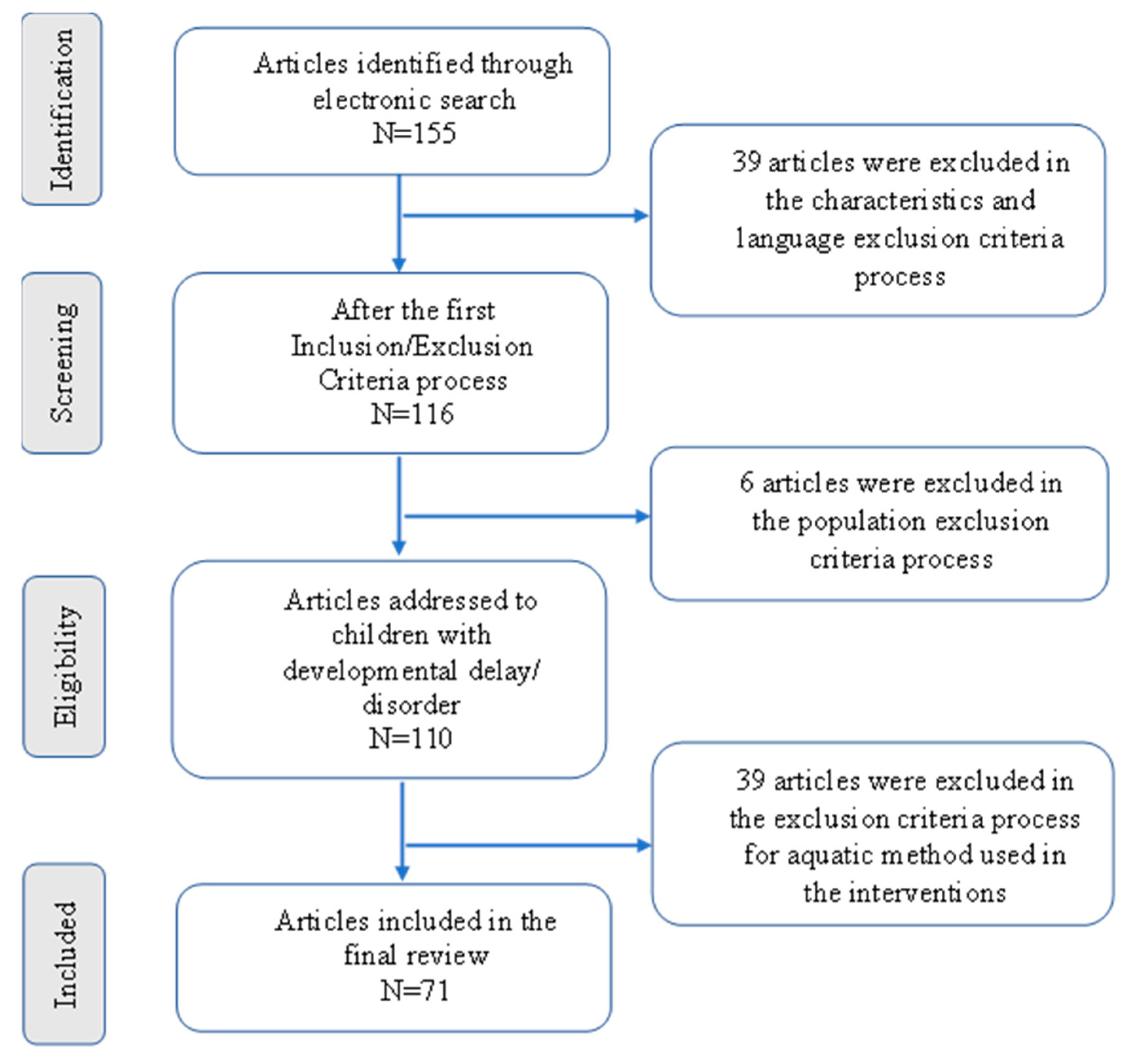

2.1. Study Design

- (1)

- Collecting all the appropriate studies between 1.1.2010 and 31.1.2020 and the selection of articles that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria established by the researchers.

- (2)

- Reviewing the selected articles for all the positive results.

- (3)

- Carrying out a linking process of all the “positive goals” to the ICF-CY framework.

- (4)

- A systematic review of the selected articles using the language of the ICF-CY framework.

2.2. Search Strategy

2.2.1. Article Selection

2.2.2. Electronic Databases

2.2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Analyzing and Linking Processes

2.3.1. Article Screening and AA Goal Selection

2.3.2. The ICF-CY Linking Process

2.4. A Short Systematic Review

3. Results

3.1. Articles Identification

3.2. Results of the Analysis

3.2.1. Article Screening and Selection of AA Positive Results

The Various Health Conditions/Diagnoses

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- Different developmental delays (DDs)—the DD group included all the studies that examined several disorders together in the same study—CP, Paresis, Spina Bifida/Myelomeningocele (SB/MMC), ASD, Down Syndrome, DD, Nonverbal Learning Disorder, Oto-Palatal-Digital Syndrome, Central and Peripheral Neurological Disorders, Psychomotor Delay, Musculoskeletal Disorders, ADHD, Noonan Syndrome [6,8,14,78,79,80,81];

- (4)

- (5)

- (6)

- (7)

- (8)

- Development Coordination Disorder (DCD) [9];

- (9)

- Down Syndrome [98];

- (10)

- Rett Syndrome [99].

Intervention Methods

Assessment Tools

Positive Intervention Results

3.3. The ICF-CY Linking Process Results

3.3.1. The ICF-CY Categories

3.3.2. The Most Used Components and Categories of the ICF-CY

4. Discussion

- -

- Quality of life is a very broad concept and is a very important subject in every person’s life [23]. According to the WHO, the definition of QoL depends on the perception of each person of their position in life within the context of their environment, such as their culture, the value systems they were raised under, and their standards, all of which are in relation to the person’s own life goals [22,25,100,101]. This important concept still does not have a structured and clear definition in the model. Thus, in our attempts to link different positive goals from the studies that referred to QOL, we had to expand each individual goal and identify the specific area of quality of life that the authors referred to in their article. The authors used many different tools, for example, the Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children (CPQOL) [43], Health-related quality of life—HRQOL [81] or the Short Form-36 items (SF-36), and the Burn Specific Health Scale Brief (BSHS-B) [102].

- -

- The definition of well-being in the framework of the ICF is very short and concise—“Well-being is a general term encompassing the total universe of human life domains, including physical, mental and social aspects, that make up what can be called a “good life” [22] (p. 227)”. Although this is a very important concept, there is not much reference to it in the model; references are only in areas related to health and health systems, and not in areas of employment, education, etc.

- -

- The goals connected to activities of daily living were very difficult to link. ADLs are defined as “tasks that are fundamental to supporting participation across school, home and community environments” [110] (p. 223). In the categories of the ICF-CY framework, each of these activities is defined separately within the components of “Activities and Participation”. There is no specific reference to this definition of functioning as a whole. For example, Zanobini and Solari [77], referred to the “self-help skill” goal from the ABC questionnaire. The areas they referred to focused on independence in toilets, eating, drinking, and dressing. To relate this goal to ICF-CY, it was necessary to refer to eight different ICF-CY categories.

- -

- Changes over time or due to interventions for a different health status or in various bodily functions, such as pain, muscle tone, etc., are impossible to link. Terms such as “improved”, “increased”, “more”, and “severity”, which indicate changes in the condition over time or intervention, do not have clear scales and definitions within the ICF-CY model [25,101]. For a linking process to be possible in these cases, in their study, the researchers must use the qualifiers which can offer information about the amount of change. Without specified qualifiers, these terms have no clear meaning in the ICF-CY framework. In addition, changes in movement characteristics such as in gait analysis, i.e., speed, stride length, dynamic balance, etc., do not have appropriate definitions within the ICF-CY framework.

- (a)

- The environment component: A gratifying finding was that environment as a whole became part of the areas which the researchers refer to, and especially areas related to the AE, the family, the friends, and the social connections. We found categories from the EF component only in the CP, ASD, and DIS health groups. Within the studies that examined the effect of AA on these three groups, 18 articles [6,8,14,28,33,37,39,43,45,47,49,52,53,57,65,74,75] found 22 different environmental categories that had a positive effect on children with DD who participated in AA. These 22 positive ICF-CY categories were extracted from all five chapters of this component (see Table A5 in Appendix A). The prominent areas were supports and relationships, and mainly focused on the categories related to the health professionals. Since the AE has unique properties that differ from those of land [111], it would make sense that the researchers would refer to this important issue in their studies. The AA techniques used in the studies were very diverse and included therapy, various functional activities, and participation. AA can be undertaken individually or in a group, in a controlled environment (therapy pool), or in a community pool, with therapists, friends, or family members. It is gratifying that the main reference in all studies was not only to the physical effects of this environment, but to the vital social aspects. This fact indicates that the researchers attach importance to AE as a factor affecting the social ability of children with DD.

- (b)

- The personal factor—A disturbing finding was the lack of reference to the children’s personality characteristics. These characteristics were mentioned in few studies, but were not examined at all as intervention goals in the study. The researchers Güeita-Rodríguez and associates [8,27,28] explained that their decision to ignore this component in their studies was due to the fact that it had not yet been classified in the ICF-CY. Fragala-Pinkham and her colleagues [47] recommended examining this area in future studies. Ballington and Naidoo [39] mentioned this component together with EF as factors that may influence children’s ability to participate in physical activity, but did not refer to it later in their article.

- (a)

- Movement and mobility—Within the wide variety of positive intervention goals, one can see from the results (Table 3) that the most frequently used categories in all the ICF-CY components were categories related to movement and mobility. The functions of the neuromuscular-skeletal and movement systems (BF), the structures related to movement (BS), and the mobility (A&P) chapters were the most frequently used chapters in the studies. These findings are not surprising, since the activity in the AE is considered to be an activity that stimulates movement and provides good balance control, due to AE properties such as buoyancy, up-thrust, and hydrostatic pressure [111]. This enable activities to be experienced that are sometimes very difficult on land for children with DD [4,5]. The properties of the AE, such as density, viscosity, and turbulence, along with the temperature of the water in the therapeutic pool (usually 32–34 °C), allows work on strengthening, cardiopulmonary endurance, and improving range of motion without much physical load on the skeleton and joints, and without the risk of falling [111].

- (b)

- Swimming—Notably, the field of swimming was the category that was tested the most in the various studies (21 times; Table 3). Swimming is a very important activity and a participation factor for children with developmental delays [44,114], both as a social and health factor. As Stubbs [115] concluded in his review from 2017: “Swimming remains one of the most popular forms of physical activity across the world and may offer a unique opportunity to promote, maintain and improve wellbeing across the lifespan, with potential to reach all individuals of society, regardless of gender, age, disability or socioeconomic status.” [115] (p. 27).

4.1. A Summary of the ICF-CY Review

4.2. Recommendations of the ICF-CY Review

4.3. Limitations of Our Research and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- Combining the different research studies’ results into a review with joint results and conclusions.

- (b)

- Promoting the uniformity of the outcome measures of the studies (when using the ICF-CY), which will enable researchers to examine the interrelationship between all interventions’ elements, and identify important domains within the AA goals of interventions.

- (c)

- Implementing the changes that apply among the children in terms of the various functioning components (i.e., BF, BS, A&P, EF, and PF), within the unique aquatic environment.

- (d)

- Using the ICF-CY language as a unifying factor between the various professionals working with the child in AA.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author and Year (Alphabetical Order) | Main Subject | Ages | Sample and Size | Aquatic Activity | Research Design |

| Adar, S. et al., 2017 [36] | CP | 4–17 | 32 | Conventional AT | RCT |

| Akinola, B.I. et al., 2019 [37] | CP | 1–12 | 30 | Conventional AT | RCT |

| Alaniz, M.L. et al., 2017 [58] | ASD | 3–7 | 7 | Group therapy | QE, NCG |

| Aleksandrović, M. et al., 2010 [78] | Neuromuscular Impairments—CP, Paresis, SB | 5–13 | 7 | Adapted swimming program, Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Badawy, W.M. et al., 2016 [38] | CP | 6–9 | 30 | Conventional AT | RCT |

| Ballington, S.J. & Naidoo, R. 2018 [39] | CP | 8–12 | 10 | Halliwick | RCT |

| Bayraktar, D. et al., 2019 [93] | JIA | 11–16 | 42 | Water-running program | QE, NRCT |

| Birkan, B. et al., 2010 [59] | ASD | 8–9 | 3 | Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Caputo, G. et al., 2018 [60] | ASD | 6–9 | 23 | Multisystem Aquatic Therapy | QE, NRCT |

| Carew, C. & Des, W.C. 2018 [88] | Asthma | 9–16 | 41 | Swimming | RCT |

| Chang, Y.K. et al., 2014 [96] | ADHD | 5–10 | 30 | Conventional AT—group | QE, NRCT |

| Christodoulaki, E. et al., 2018 [40] | CP | 5–15 | 8 | Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Chu, C. & Pan, C. 2012 [61] | ASD | 7–12 | 42 (21 ASD + 21 TD) | Halliwick | QE, NRCT |

| De la Cruz, R.D. & Robert, D. 2012 [41] | CP | 7–17 | 4 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Declerck, M. et al., 2013 [43] | CP | 5–13 | 7 | Halliwick | QE—A pilot study, NCG |

| Declerck, M. 2014 [44] | CP | 7–17 | 14 | Swimming intervention—Halliwick | RCT- A pilot study |

| Declerck, M. et al., 2016 [42] | CP | 7–17 | 14 | Swimming intervention—Halliwick | RCT |

| Dimitrijevic, L. et al., 2012 [45] | CP | 5–14 | 27 | Swimming intervention—Halliwick | RCT |

| Elnaggar, R. & Elshafey, M.A. 2016 [94] | JIA | 8–11 | 30 | Combined resistive underwater exercises and interferential current therapy | RCT |

| Ennis, E. 2011 [62] | ASD | 3–9 | 6 | Conventional AT, Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Fatorehchy S. et al., 2019 [46] | CP | 6–9 | 6 | Walking aquatic therapy program | QE, NCG |

| Ferreira, A.V.S. et al., 2015 [82] | DMD | 8–24 | 23 | Halliwick | QE retrospective study, NCG |

| Fragala-Pinkham, M. et al., 2010 [6] | Different disabilities—ASD, CP, DS, MMC, DD, NLD, OPTS | 6–12 | 16 | Pilot aquatic exercise program—swimming and Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Fragala-Pinkham, M.A. et al., 2011 [7] | ASD | 6–12 | 12 | Group aquatic exercise program—conventional AT | QE, NRCT |

| Fragala-Pinkham, M.A. et al., 2014 [47] | CP | 6–15 | 8 | Aquatic aerobic exercise program—individual | QE, NCG |

| Güeita-Rodríguez, J. et al., 2017 [8] | Children with Disabilities—ND, ASD, PMD, MD | children | -- | Aquatic physical therapy | EP (interview) |

| Güeita-Rodríguez, J. et al., 2018 [27] | CP | 0–18 | 34 parents | Aquatic physical therapy | EP (interview) |

| Hamed, S.A. & Fathy, K.A. 2015 [89] | Hemophilia | 7–10 | 30 | Swimming exercise program | QE, NCG |

| Hamed, S.A. et al., 2016 [98] | DS | 8–12 | 30 | Swimming training program, conventional AT | RCT |

| Hillier, S. et al., 2010 [9] | DCD | 5–8 | 12 | Halliwick | RCT |

| Hind, D. et al., 2017 [83] | DMD | 7–16 | at the end—9 | Standardized AT | QE, single-blind RCT, with nested qualitative research |

| Honório, S. et al., 2013 [84] | DMD | 9–11 | 7 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Honorio, S. et al., 2016 [85] | DMD | 9–11 | 3 | Conventional AT | QE, NRCT |

| Ilinca, I. et al., 2015 [79] | Children with Disabilities—DS, ASD, CP | 10–16 | 6 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Jorgić, B. et al., 2014 [48] | CP | 6–17 | 15 | Halliwick, backstroke swimming | QE, NCG |

| Jorgić, B. et al., 2012 [49] | CP | 8–10 | 7 | Halliwick, swimming | QE, NCG |

| Jull, S. & Mirenda, P. 2016 [63] | ASD | 5–8 | 8 | Swimming | QE, NCG |

| Kafkas, A.S. & Gökmen, Ö.Z.E.N. 2015 [64] | ASD | 8 | 1 | Swimming | QE, NCG, A Pilot Study |

| Kim, K.H. & Hwa, K.S. 2017 [50] | CP | 3–7 | 20 | Conventional AT | QE, one group pretest-posttest design |

| Kim, K.H. et al., 2018 [80] | Different Disabilities—not detailed | 5–20 | 10 | Swimming exercise program | QE, NCG |

| Lai, C.J. et al., 2015 [51] | CP | 4–12 | 24 | Halliwick | QE, NRCT |

| Lawson, L.M. & Little L, 2017 [67] | ASD | 5–12 | 10 | Sensory Enhanced Aquatics | QE, NCG |

| Lawson, L.M. et al., 2019 [65] | ASD | 4–18 | 14 children; 14 Parents | Family water activities | QE, NCG |

| Lawson, L.M. et al., 2014 [66] | ASD | 4–18 | 42 | Sensory-supported swimming® lessons | QE, NCG |

| Maniu, D.A. et al., 2013 [52] | CP | 8–16 | 24 | Aquatic therapy program | QE, NCG |

| Maniu, D.A. et al., 2013 [53] | CP | 8–16 | 24 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Wadu Mesthri, S. 2019 [56] | CP | 7–11 | 5 | Conventional AT | QE, pretest-posttest design, NCG |

| Mills, W. et al., 2020 [68] | ASD | 6–12 | 8 | Conventional AT | RCT, A Pilot Trial |

| Olama, K.A. et al., 2015 [54] | CP | 5–7 | 30 | Conventional AT | RCT |

| Oriel, K.N. et al., 2016 [69] | ASD | 6–11 | 8 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG, A Pilot Study |

| Oriel, K.N. et al., 2012 [81] | Different Disabilities—SB, ADHD, CP, ASD, NS | 7–18 | 23 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Pan, C.Y. 2010 [10] | ASD | 6–9 | 16 | Halliwick | QE, controlled single-blind design |

| Pan, C.Y. 2011 [70] | ASD | 7–12 | 15 with ASD, 15 siblings | Halliwick | QE, NRCT |

| Pushkarenko, K. et al., 2016 [71] | ASD | 11–17 | 3 | Conventional AT | QE, An interrupted time series design (A/B/A), A Pilot Study |

| Ramírez, N.P. et al., 2019 [95] | JIA | 8–18 | 46 | Watsu and conventional AT | RCT |

| Ryu, K. et al., 2016 [55] | CP | 8–48 (aquatic group—9–13) | 32 | Assisted aquatic movement | RCT |

| Salem, E.Y. et al., 2016 [90] | Asthma | 6–12 | 40 | Conventional AT | QE |

| Samhan, A. et al., 2020 [91] | Juvenile Dermatomyositis | 10–16 | 14 | Conventional AT | QE, A 2 × 2 Controlled-Crossover Trial |

| Santos, C.P.A. et al., 2016 [86] | CMD | 6 | 1 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG, A case study |

| Shams-Elden, M. 2017 [72] | ASD | 8–11 | 10 | Halliwick therapy | QE, NCG, A case report |

| Silva, K.M. 2012 [87] | DMD | 12 | 1 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG, A case study |

| Silva, L.A.D. et al., 2020 [97] | ADHD | 11–14 | 20 | Swimming–learning program | RCT |

| Stan, A.E. 2012 [92] | Overweight | 5–8 | 7 | Conventional AT, running, swimming | QE, NCG |

| Torres, L.E. et al., 2019 [99] | Rett syndrome | 4–7 | 3 | WaterFit MITAF program (Integral Method of Functional Aquatic Work) | QE, NCG, A case report |

| Vaščáková, T. et al., 2015 [14] | Severe Disabilities—CP, ASD | 4–7 | 10 | Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Wilson, K.E. 2019 [73] | ASD | 4–13 | 6 | Conventional AT | QE, NCG |

| Yanardag, M. et al., 2013 [74] | ASD | 6–8 | 3 | Aquatic play skills intervention—based on Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Yanardag, M. et al., 2015 [75] | ASD | 6 | 3 | Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Yilmaz, I. et al., 2010 [76] | ASD | 9 | 3 | Halliwick | QE, NCG |

| Zanobini, M. & Solari, S. 2019 [77] | ASD | 3–8 | 25 | “Water as a Mediator of Communication” program | QE |

| Zverev, Y. & Kurnikova, M. 2016 [57] | CP | 5–17 | 13 | Community-based group aquatic program—aimed to balance | QE, NCG |

| Measurement Tools | CP | ASD | DMD+ CMD | DD | Health Con. | JIA | ADHD | DCD | Down Syn. | Rett Syn. | Total | |

| 1 | A Gima Oxy-4 oximeter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | A goniometer | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 3 | A sleep log | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | A Spirometer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 5 | A survey for experts | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | Ability to increase and maintain swimming skill | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 7 | activity limitations measure (ACTIVLIM) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 8 | American Red Cross learn-to-swim levels | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 9 | Anthropometric circumference measurements | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 10 | Aquatic skills checklist (ASC) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11 | Balance Master System | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 12 | Barthel ADL Index | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | Basic Motor Ability Test-Revised (BMAT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 14 | Biodex balance system | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 15 | Biodex Gait Trainer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 16 | blood collection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | Brockport Physical Fitness Test (BPFT) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 18 | Carefussion PulmoLife spirometer | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 19 | Carer quality of life (CarerQoL) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 20 | Cerebral Palsy Quality-of-Life–parent proxy scale (CP QoL—parent) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 21 | Child Depression Inventory (CDI) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 22 | Child Health Utility 9D Index (CHU9D) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 23 | Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 24 | Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 25 | Children’s OMNI Scale of Perceived Exertion (OMNI RPE) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 26 | Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 27 | Compliance test | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 28 | Computerized Evaluation Protocol of Interactions in Physical Education (CEPI-PE) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 29 | Demographic form | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 30 | document investigation and observation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 31 | EKS—Egen Klassifikation Scale | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 32 | Electrically-braked cycle ergometers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 33 | Electroencephalograms | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 34 | electromyography (EMG) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 35 | Energy Expenditure Index (EEI) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 36 | Enjoyment regarding the swimming intervention | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 37 | forced vital capacity (FVC) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 38 | Functional Independence Measure (FIM) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 39 | functional reach test (FRT) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 40 | Health and social care resource-use questionnaire | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 41 | health-related quality of life (HRQoL) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 42 | Heart rate | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 43 | Hoffman reflex | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 44 | HUMAC NORM—Isokinetic Dynamometer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 45 | Humphries’ Assessment Of Aquatic Readiness (HAAR) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 46 | Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 47 | Isometric muscle strength | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 48 | Jamar Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 49 | Jebsen-Taylor Hand Function test | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 50 | Kinemtaic gait parameters | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 51 | Life Habits Short Form questionnaire (LIFE-H) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 52 | Lung pressures | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 53 | Measures of program acceptability and safety | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 54 | Mercury sphygmomanometer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 55 | Metabolic Gas Analysis Systems | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 56 | Modified Ashworth Spasticity (MAS) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 57 | Movement Assessment Battery for Children—Second Edition (Movement M-ABC, ABC-2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 58 | multidimensional fatigue scale (MFI) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 59 | North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 60 | 0ne—minute fast walk test | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 61 | Paediatric Escola Paulista de Medicina Range of Motion Scale (pEPM-ROM) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 62 | Patient Global Assessment (PGA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 63 | Pediatric Balance Scale (PBS) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 64 | Pediatric Evaluation of Disability—PEDI (PEDI-NL; M-pedi; PEDI-CAT) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 65 | Pediatric Reach Test (PRT) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 66 | Peer Sociometric Nomination Assessment (Friendship Questionnaire) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 67 | Percentage of fat mas | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 68 | Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale scores (PACES) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 69 | Physical Activity Index | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 70 | Pictorial Scale of Perceived Competence and Social Acceptance (PSPCSA) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 71 | Piers-Harris 2 Children’s Self-Concept Scale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 72 | Pool tests—20 m run, the standing broad jump test, Mushroom Float, and Walking | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 73 | Program satisfaction—evaluation questionnaire for parents/children | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 74 | Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children (CP QoL-Child) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 75 | Questionnaire for measuring quality of life in children and adolescents (KINDLR) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 76 | Questionnaire on Parent’s Perception of Changes in their Child’s Participation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 77 | School Social Behavior Scales (SSBS–2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 78 | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 79 | Sensory Profile Caregiver Questionnaire | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 80 | Shuttle Run Test (SRT-I & SRT-III) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 81 | six-min walk distance (6 MWD) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 82 | Six-Minute Walk Test (6 MWT) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 83 | Skin Disease Activity Score (Dasskin) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 84 | Skinfolds | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 85 | Social and ecological validity survey | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 86 | Social Responsiveness Scale, 2nd edition (SRS-2) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 87 | Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 88 | Social validity—parent questionnaires | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 89 | Spatial-temportal gait variables | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 90 | Sustainability of the aquatic exercise program | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 91 | Swimming Classification Scale (SCS) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 92 | Swimming skill acquisition | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 93 | Swimming With Independent Measure (SWIM) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 94 | Ten-joints Global range of motion score (GROMS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 95 | Ten-meter walking speed (10-MWT) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 96 | The 16-m modified PACER | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 97 | The amount of training time required to achieve a skill | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 98 | The anaerobic-to-aerobic power ratio | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 99 | The Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 100 | The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 101 | The Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOT) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 102 | The Carefussion MicroPeak flow meter | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 103 | The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 104 | The Feeling Scale | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 105 | The Felt Arousal Scale (FAS) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 106 | The Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM-88/GMFM-66) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 107 | The half mile walk/run | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 108 | The International Physical Activity Questionnaire—IPAQ—parents | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 109 | The Korean-trunk control measurement scale (K-TCMS) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 110 | The Körperkoordinations Test für Kinder (KTK) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 111 | The modified curl-up and isometric push-up tests | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 112 | The Motor Function Measurement (MFM) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 113 | The National Physical Fitness Survey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 114 | The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory quality of life (PedsQL-CP) | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 115 | The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 116 | The Progressive Aerobic cardiovascular fitness (PACER) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 117 | The sit-and-reach test | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 118 | the TAC Cancellation Attention Test | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 119 | The Timed Up and Go test (TUG) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 120 | The Trail Making Test (TMT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 121 | The Ventilatory Function Tests (VFTs) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 122 | The Vignos scale | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 123 | The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Faces Pain Scale (FPS-R) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 124 | The Wee Functional Independence measure (WeeFIM) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 125 | Timed Up and Down Stairs (TUDS) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 126 | Verbal evaluation Test | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 127 | Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 128 | Water Oriented Test Alyn (WOTA) | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 129 | Weight and BMI | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 130 | Wingate Test | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 131 | YMCA Water Skills Checklist | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 132 | Zigzag agility test | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total Measurements | 74 | 45 | 22 | 17 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 196 |

| N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category | N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category | N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category |

| 1 | b110 | Consciousness functions | 34 | b176 | Mental function of sequencing complex movements | 67 | b5253 | Faecal continence |

| 2 | b114 | Orientation functions | 35 | b180 | Experience of self and time functions | 68 | b530 | Weight maintenance functions |

| 3 | b1143 * | Orientation to objects | 36 | b210 | Seeing functions | 69 | b6202 | Urinary continence |

| 4 | b117 | Intellectual functions | 37 | b2300 * | Sound detection | 70 | b710 | Mobility of joint functions |

| 5 | b122 | Global psychosocial functions | 38 | b235 | Vestibular functions | 71 | b7101 | Mobility of several joints |

| 6 | b125 | Dispositions and intra-personal functions | 39 | b2350 | Vestibular function of position | 72 | b715 | Stability of joint functions |

| 7 | b1250 | Adaptability | 40 | b2351 | Vestibular function of balance | 73 | b720 | Mobility of bone functions |

| 8 | b1252 | Activity level | 41 | b2352 | Vestibular function of determination of movement | 74 | b730 | Muscle power functions |

| 9 | b1254 | Persistence | 42 | b250 | Taste function | 75 | b7300 | Power of isolated muscles and muscle groups |

| 10 | b126 | Temperament and personality functions | 43 | b255 | Smell function | 76 | b7301 | Power of muscles of one limb |

| 11 | b1263 | Psychic stability | 44 | b260 | Proprioceptive function | 77 | b7302 | Power of muscles of one side of the body |

| 12 | b1264 | Openness to experience | 45 | b265 | Touch function | 78 | b7303 | Power of muscles in lower half of the body |

| 13 | b1266 | Confidence | 46 | b270 | Sensory functions related to temperature and other stimuli | 79 | b7304 | Power of muscles of all limbs |

| 14 | b130 | Energy and drive functions | 47 | b2703 | Sensitivity to a noxious stimulus | 80 | b7305 | Power of muscles of the trunk |

| 15 | b1301 | Motivation | 48 | b280 | Sensation of pain | 81 | b7306 | Power of all muscles of the body |

| 16 | b1304 | Impulse control | 49 | b2800 | Generalized pain | 82 | b735 | Muscle tone functions |

| 17 | b134 | Sleep functions | 50 | b310 | Voice functions | 83 | b740 | Muscle endurance functions |

| 18 | b1340 | Amount of sleep | 51 | b330 | Fluency and rhythm of speech functions | 84 | b750 | Motor reflex functions |

| 19 | b1342 | Maintenance of sleep | 52 | b410 | Heart functions | 85 | b755 | Involuntary movement reaction functions |

| 20 | b1344 | Functions involving the sleep cycle | 53 | b415 | Blood vessel functions | 86 | b760 | Control of voluntary movement functions |

| 21 | b140 | Attention functions | 54 | b420 | Blood pressure functions | 87 | b7600 | Control of simple voluntary movements |

| 22 | b144 | Memory functions | 55 | b4302 | Metabolite-carrying functions of the blood | 88 | b7601 | Control of complex voluntary movements |

| 23 | b147 | Psychomotor functions | 56 | b435 | Immunological system functions | 89 | b7602 | Coordination of voluntary movements |

| 24 | b1470 | Psychomotor control | 57 | b440 | Respiration functions | 90 | b7603 | Supportive functions of arm or leg |

| 25 | b1471 | Quality of psychomotor functions | 58 | b4401 | Respiratory rhythm | 91 | b7608 | Control of voluntary movement functions, other specified- Half km/4 points |

| 26 | b152 | Emotional functions (happiness) | 59 | b4402 | Depth of respiration | 92 | b761 | Spontaneous movements |

| 27 | b1520 | Appropriateness of emotion | 60 | b445 | Respiratory muscle functions | 93 | b7611 | Specific spontaneous movements |

| 28 | b1522 | Range of emotion | 61 | b450 | Additional respiratory functions | 94 | b765 | Involuntary movement functions |

| 29 | b156 | Perceptual functions | 62 | b455 | Exercise tolerance functions | 95 | b7653 | Stereotypies and motor perseveration |

| 30 | b160 | Thought functions | 63 | b4550 | General physical endurance | 96 | b770 | Gait pattern functions |

| 31 | b163 | Basic cognitive functions | 64 | b4552 | Fatiguability | 97 | b780 | Sensations related to muscles and movement functions |

| 32 | b164 | Higher-level cognitive functions | 65 | b510 | Ingestion functions | 98 | b840 | Sensation related to the skin |

| 33 | b1643 | Cognitive flexibility | 66 | b525 | Defecation functions |

| N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category | N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category |

| 1 | d110 | Watching | 71 | d430 | Lifting and carrying objects |

| 2 | d115 | Listening | 72 | d4302 | Carrying in the arms |

| 3 | d120 | Other purposeful sensing | 73 | d435 | Moving objects with lower extremities |

| 4 | d1201 | Touching | 74 | d4351 | Kicking |

| 5 | d1202 | Smelling | 75 | d440 | Fine hand use |

| 6 | d1203 | Tasting | 76 | d4400 | Picking up |

| 7 | d129 | Purposeful sensory experiences, other specified and unspecified | 77 | d4402 | Manipulating |

| 8 | d130 | Copying | 78 | d445 | Hand and arm use |

| 9 | d131 | Learning through actions with objects | 79 | d4452 | Reaching |

| 10 | d1310 | Learning through simple actions with a single object | 80 | d4454 | Throwing |

| 11 | d132 | Acquiring information | 81 | d4455 | Catching |

| 12 | d135 | Rehearsing | 82 | d450 | Walking |

| 13 | d137 | Acquiring concepts | 83 | d4500 | Walking short distances |

| 14 | d140 | Learning to read | 84 | d4501 | Walking long distances |

| 15 | d145 | Learning to write | 85 | d4508 | Walking, other specified—walking in water |

| 16 | d155 | Acquiring skills | 86 | d455 | Moving around |

| 17 | d159 | Basic learning, other specified and unspecified | 87 | d4550 | Crawling |

| 18 | d160 | Focusing attention | 88 | d4551 | Climbing |

| 19 | d1601 | Focusing attention to changes in the environment | 89 | d4552 | Running |

| 20 | d161 | Directing attention | 90 | d4553 | Jumping |

| 21 | d170 | Writing | 91 | d4554 | Swimming |

| 22 | d175 | Solving problems | 92 | d4555 | Scooting and rolling |

| 23 | d177 | Making decisions | 93 | d4558 | Moving around, other specified -walking backwards/KN walk/with hand support |

| 24 | d210 | Undertaking a single task | 94 | d460 | Moving around in different locations |

| 25 | d2103 | Undertaking a single task in a group | 95 | d465 | Moving around using equipment |

| 26 | d220 | Undertaking multiple tasks | 96 | d469 | Walking and moving, other specified and unspecified |

| 27 | d2203 | Undertaking multiple tasks in a group | 97 | d510 | Washing oneself |

| 28 | d230 | Carrying out daily routine | 98 | d520 | Caring for body parts |

| 29 | d2300 | Following routines | 99 | d530 | Toileting |

| 30 | d2302 | Completing the daily routine | 100 | d540 | Dressing |

| 31 | d2303 | Managing one’s own activity level | 101 | d550 | Eating |

| 32 | d2304 | Managing changes in daily routine | 102 | d560 | Drinking |

| 33 | d240 | Handling stress and other psychological demands | 103 | d570 | Looking after one’s health |

| 34 | d2401 | Handling stress | 104 | d571 | Looking after one’s safety |

| 35 | d250 | Managing one’s own behavior | 105 | d598 | Self-care, other specified |

| 36 | d2500 | Accepting novelty | 106 | d599 | Self-care, unspecified |

| 37 | d2504 | Adapting activity level | 107 | d710 | Basic interpersonal interactions |

| 38 | d310 | Communicating with—receiving—spoken messages | 108 | d7101 | Appreciation in relationships—satisfaction |

| 39 | d3101 | Comprehending simple spoken messages | 109 | d7102 | Tolerance in relationships |

| 40 | d3102 | Comprehending complex spoken messages | 110 | d71041 | Maintaining social interactions |

| 41 | d315 | Communicating with—receiving—nonverbal messages | 111 | d7105 | Physical contact in relationships |

| 42 | d325 | Communicating with—receiving—written messages | 112 | d7106 | Differentiation of familiar persons |

| 43 | d330 | Speaking | 113 | d720 | Complex interpersonal interactions |

| 44 | d331 | Pre-talking | 114 | d7200 | Forming relationships |

| 45 | d332 | Singing | 115 | d7202 | Regulating behaviors within interactions |

| 46 | d335 | Producing nonverbal messages | 116 | d7203 | Interacting according to social rules |

| 47 | d3352 | Producing drawings and photographs | 117 | d730 | Relating with strangers |

| 48 | d345 | Writing messages | 118 | d740 | Formal relationships |

| 49 | d350 | Conversation | 119 | d7400 | Relating with persons in authority |

| 50 | d3500 | Starting a conversation | 120 | d7402 | Relating with equals |

| 51 | d355 | Discussion | 121 | d750 | Informal social relationships |

| 52 | d410 | Changing basic body position | 122 | d7504 | informal relationships with peers |

| 53 | d4100 | Lying down | 123 | d760 | Family relationships |

| 54 | d4101 | Squatting | 124 | d7600 | Parent-child relationships |

| 55 | d4102 | Kneeling | 125 | d7601 | Child-parent relationships |

| 56 | d4103 | Sitting | 126 | d7602 | Sibling relationships |

| 57 | d4104 | Standing | 127 | d8151 | Maintaining preschool educational program |

| 58 | d4105 | Bending | 128 | d820 | School education |

| 59 | d4106 | Shifting the body’s center of gravity | 129 | d8201 | Maintaining educational program |

| 60 | d4107 | Rolling over | 130 | d835 | School life and related activities |

| 61 | d4108 | Changing basic body position, other specified—from sitting to 4 points/from lying to 4 points/half kn./Turning | 131 | d880 | Engagement in play |

| 62 | d415 | Maintaining a body position | 132 | d8800 | Solitary play |

| 63 | d4152 | Maintaining a kneeling position | 133 | d910 | Community life |

| 64 | d4153 | Maintaining a sitting position | 134 | d9103 | Informal community life |

| 65 | d4154 | Maintaining a standing position | 135 | d920 | Recreation and leisure |

| 66 | d4155 | Maintaining head position | 136 | d9200 | Play |

| 67 | d4158 | Maintaining a body position, other specified—balance in the water/4 points/3 points/half kn./one leg | 137 | d9201 | Sports |

| 68 | d420 | Transferring oneself | 138 | d9205 | Socializing |

| 69 | d4200 | Transferring oneself while sitting | |||

| 70 | d429 | Changing and maintaining body position, other specified and unspecified |

| N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category |

| 1 | e115 | Products and technology for personal use in daily living |

| 2 | e130 | Products and technology for education |

| 3 | e150 | Design, construction and building products, and technology of buildings for public use |

| 4 | e225 | Climate |

| 5 | e240 | Light |

| 6 | e250 | Sound |

| 7 | e260 | Air quality |

| 8 | e310 | Immediate family |

| 9 | e315 | Extended family |

| 10 | e325 | Acquaintances, peers, colleagues, neighbors and community members |

| 11 | e330 | People in positions of authority |

| 12 | e355 | Health professionals |

| 13 | e410 | Individual attitudes of immediate family members |

| 14 | e420 | Individual attitudes of friends |

| 15 | e445 | Individual attitudes of strangers |

| 16 | e450 | Individual attitudes of health professionals |

| 17 | e455 | Individual attitudes of health-related professionals |

| 18 | e460 | Societal attitudes |

| 19 | e5301 | Utilities systems |

| 20 | e580 | Health services, systems and policies |

| 21 | e5802 | Health policies |

| 22 | e585 | Education and training services, systems and policies |

| N. | ICF-CY Code | ICF-CY Category |

| 1 | s240 | Structure of external ear |

| 2 | s250 | Structure of middle ear |

| 3 | s310 | Structure of nose |

| 4 | s430 | Structure of respiratory system |

| 5 | s710 | Structure of head and neck region |

| 6 | s720 | Structure of shoulder region |

| 7 | s730 | Structure of upper extremity |

| 8 | s740 | Structure of pelvic region |

| 9 | s750 | Structure of lower extremity |

| 10 | s760 | Structure of trunk |

| 11 | s770 | Additional musculoskeletal structures related to movement |

| 12 | s810 | Structure of areas of skin |

| 1 | s240 | Structure of external ear |

| 2 | s250 | Structure of middle ear |

| 3 | s310 | Structure of nose |

| 4 | s430 | Structure of respiratory system |

| 5 | s710 | Structure of head and neck region |

| 6 | s720 | Structure of shoulder region |

| 7 | s730 | Structure of upper extremity |

| 8 | s740 | Structure of pelvic region |

| 9 | s750 | Structure of lower extremity |

| 10 | s760 | Structure of trunk |

References

- Rohn, S.; Novak Pavlic, M.; Rosenbaum, P. Exploring the use of Halliwick aquatic therapy in the rehabilitation of children with disabilities: A scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2021, 47, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokaw, M.M. Aquatic Therapy: An Interprofessional Resource Focusing on Children with Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, ND, USA, 15 April 2022. Available online: https://commons.und.edu/ot-grad/493 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Mujawar, M.M. A systematic review of the effects of aquatic therapy on motor functions in children with cerebral palsy. Reabil. Moksl. slauga, Kineziter. Ergoter. 2022, 2, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Darrah, J. Aquatic exercise for children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2005, 47, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kārkliņa, B.; Declerck, M.; Daly, D.J. Quantification of aquatic interventions in children with disabilities: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2013, 7, 344–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M.; O’Neil, M.E.; Haley, S.M. Summative evaluation of a pilot aquatic exercise program for children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2010, 3, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M.A.; Haley, S.M.; O’Neil, M.E. Group swimming and aquatic exercise programme for children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. Dev. Neurorehabil 2011, 14, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güeita-Rodríguez, J.; García-Muro, F.; Cano-Díez, B.; Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.L.; Lambeck, J.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Identification of intervention categories for aquatic physical therapy in pediatrics using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health-Children and Youth: A global expert survey. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2017, 21, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, S.; McIntyre, A.; Plummer, L. Aquatic physical therapy for children with developmental coordination disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2010, 30, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.Y. Effects of water exercise swimming program on aquatic skills and social behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2010, 14, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, F. The individual physical health benefits of swimming: A literature review. In The Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Swimming; Cumming, I., Ed.; Swim England’s Swimming and Health Commission: London, UK, 2017; pp. 8–25. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/media/11765/health-and-wellbeing-benefits-of-swimming-report.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Scott, J.; Wozencroft, A.; Nocera, V.; Webb, K.; Anderson, J.; Blankenburg, A.; Watson, D.; Lowe, S. Aquatic therapy interventions and disability: A recreational therapy perspective. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2020, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Güeita-Rodríguez, J.; Ogonowska-Slodownik, A.; Morgulec-Adamowicz, N.; Martín-Prades, M.L.; Cuenca-Zaldívar, J.N.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Effects of aquatic therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder on social competence and quality of life: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaščáková, T.; Kudláček, M.; Barrett, U. Halliwick Concept of Swimming and its Influence on Motoric Competencies of Children with Severe Disabilities. Eur. J. Adapt. Phys. Act. 2015, 8, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.; Rosenbaum, P.; Gorter, J.W. Exploring the aquatic environment for disabled children: How we can conceptualize and advance interventions with the ICF. Crit. Rev. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 25, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, A.; Fayed, N.; Bickenbach, J.; Prodinger, B. Refinements of the ICF Linking Rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, A.; Geyh, S.; Chatterji, S.; Kostanjsek, N.; Ustun, B.; Stucki, G. ICF Linking Rules: An update based on lessons learned. J. Rehabil. Med. 2005, 37, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42407/9241545429.pdf;jsessionid=EFB5A18701A32C05186DECC5CD1CBEB2?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Madden, R.H.; Bundy, A. The ICF has made a difference to functioning and disability measurement and statistics. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustenberger, N.A.; Prodinger, B.; Dorjbal, D.; Rubinelli, S.; Schmitt, K.; Scheel-Sailer, A. Compiling standardized information from clinical practice: Using content analysis and ICF linking rules in a goal-oriented youth rehabilitation program. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Children and Youth Version: ICF-CY; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43737/1/9789241547321_eng.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Simeonsson, R.J.; Björck-Åkessön, E.; Lollar, D.J. Communication, disability, and the ICF-CY. Augment. Altern. Commun. 2012, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballert, C.S.; Hopfe, M.; Kus, S.; Mader, L.; Prodinger, B. Using the refined ICF Linking Rules to compare the content of existing instruments and assessments: A systematic review and exemplary analysis of instruments measuring participation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, J.; Wright, V.; Rosenbaum, P. The ICF model of functioning and disability: Incorporating quality of life and human development. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2010, 13, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Stewart, D.; Rosenbaum, P.; Baptiste, S.; De Camargo, O.K.; Gorter, J.W. Using the ICF in transition research and practice? Lessons from a scoping review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 72, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güeita-Rodríguez, J.; García-Muro, F.; Rodríguez-Fernández, ÁL.; Lambeck, J.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Palacios-Ceña, D. What areas of functioning are influenced by aquatic physiotherapy? Experiences of parents of children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2018, 21, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güeita-Rodríguez, J.; García-Muro, F.; Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.l.; Cano-Díez, B.; Chávez-Santacruz, D.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Preliminary aquatic physical therapy core sets for children and youth with neurological disorders: A consensus process. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 31, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiariti, V.; Klassen, A.F.; Cieza, A.; Sauve, K.; O’Donnell, M.; Armstrong, R.; Mâsse, L.C. Comparing contents of outcome measures in cerebral palsy using the International Classification of Functioning (ICF-CY): A systematic review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2014, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolfsson, M.; Sjöman, M.; Björck-Åkesson, E. ICF-CY as a framework for understanding child engagement in preschool. Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, A.-C.; Granlund, M.; Santacroce, S.J.; Enskär, K.; Carlstein, S.; Björk, M. Using ICF to describe problems with functioning in everyday life for children who completed treatment for brain tumor: An analysis based on professionals’ documentation. Front. Rehabilit. Sci. 2021, 2, 708265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadar-Frumer, M.; Ten Napel, H.; Yuste-Sánchez, M.J.; Rodríguez-Costa, I. The international classification of functioning, disability and health: Accuracy in aquatic activities reports among children with developmental delay. Children 2023, 10, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OʼNeil, M.E.; Fragala-Pinkham, M. Commentary on: “Preliminary aquatic physical therapy core sets for children and youth with neurological disorders: A consensus process”. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 31, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, L.E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccoby, E.E. Middle childhood in the context of the family. In Development during Middle Childhood: The Years from Six to Twelve; Collins, W.A., National Research Council, Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 184–239. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216771/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Adar, S.; Dündar, Ü.; Demirdal, Ü.S.; Ulaşlı, A.M.; Toktaş, H.; Solak, Ö. The effect of aquatic exercise on spasticity, quality of life, and motor function in cerebral palsy. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 63, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, B.I.; Gbiri, C.A.; Odebiyi, D.O. Effect of a 10-week aquatic exercise training program on gross motor function in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2019, 25, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, W.M.; Mohamed, B.I. Comparing the effects of aquatic and land-based exercises on balance and walking in spastic diplegic cerebral palsy children. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2016, 84, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ballington, S.J.; Naidoo, R. The carry-over effect of an aquatic-based intervention in children with cerebral palsy. Afr. J. Disabil. 2018, 7, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulaki, E.; Chandolias, K.; Hristara-Papadopoulou, A. The effect of hydrotherapy-Halliwick concept on the respiratory system of children with cerebral palsy. BAOJ Pediat 2018, 4, 063. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz, R.D. Effects of Aquatic Exercise on Gait Parameters in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Master’s Thesis, California State University, Northridge, CA, USA, 2012. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10211.2/1616 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Declerck, M.; Verheul, M.; Daly, D.; Sanders, R. Benefits and enjoyment of a swimming intervention for youth with cerebral palsy: An RCT study. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2016, 28, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, M.; Feys, H.; Daly, D. Benefits of swimming for children with cerebral palsy: A pilot study a pilot study. Serb. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 7, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Declerck, M. Swimming and the Physical, Social and Emotional Well-Being of Youth with Cerebral Palsy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, 4 July 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1842/9459 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Dimitrijevic, L.; Aleksandrovic, M.; Madic, D.; Okicic, T.; Radovanovic, D.; Daly, D. The effect of aquatic intervention on the gross motor function and aquatic skills in children with cerebral palsy. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 32, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatorehchy, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Rassafiani, M. The effect of aquatic therapy at different levels of water depth on functional balance and walking capacity in children with cerebral palsy. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res. 2019, 9, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragala-Pinkham, M.A.; Smith, H.J.; Lombard, K.A.; Barlow, C.; O’Neil, M.E. Aquatic aerobic exercise for children with cerebral palsy: A pilot intervention study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2014, 30, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgic, B.; Aleksandrović, M.; Dimitrijević, L.; Živković, D.; Özsari, M.; Arslan, D. The effects of a program of swimming and aquatic exercise on flexibility in children with cerebral palsy. Facta Univ. Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport. 2014, 12, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgić, B.; Dimitrijević, L.; Aleksandrović, M.; Okicic, T.; Madic, D.; Radovanovic, D. The swimming program effects on the gross motor function, mental adjustment to the aquatic environment, and swimming skills in children with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Spec. Edukac. Rehabil. 2012, 11, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Hwa, K.S. The effects of water-based exercise on postural control in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Phys. Ther. Rehabil. Sci. 2017, 6, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.J.; Liu, W.Y.; Yang, T.F.; Chen, C.L.; Wu, C.Y.; Chan, R.C. Pediatric aquatic therapy on motor function and enjoyment in children diagnosed with cerebral palsy of various motor severities. J. Child. Neurol. 2015, 30, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniu, D.A.; Maniu, E.A.; Benga, I. Effects of an aquatic therapy program on vital capacity, quality of life and physical activity index in children with cerebral palsy. Hum. Vet. Med. 2013, 5, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Maniu, D.A.; Maniu, E.A.; Benga, I. Influencing the gross motor function, spasticity and range of motion in children with cerebral palsy by an aquatic therapy intervention program. Stud. Univ. Babes-Bolyai Educ. Artis Gymnast. 2013, 58, 101–115. [Google Scholar]

- Olama, K.A.; Hala, I.K.; Shimaa, N.A. Impact of aquatic exercise program on muscle tone in spastic hemiplegic children with cerebral palsy. Clin. Med. J. 2015, 1, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Ali, A.; Kwon, M.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.; Lee, G.; Kim, J. Effects of assisted aquatic movement and horseback riding therapies on emotion and brain activation in patients with cerebral palsy. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 3283–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadu Mesthri, S. The Effects of an Individual Hydrotherapy Program on Static and Dynamic Balance in Children with Cerebral Palsy in Sri Lanka. Master’s Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 24 October 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1993/34361 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Zverev, Y.; Kurnikova, M. Adapted community-based group aquatic program for developing balance: A pilot intervention study involving children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2016, 16, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaniz, M.L.; Rosenberg, S.S.; Beard, N.R.; Rosario, E.R. The effectiveness of aquatic group therapy for improving water safety and social interactions in children with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot program. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 4006–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkan, B.; Yılmaz, İ.; Konukman, F.; Birkan, B.; Özen, A.; Yanardağ, M.; C̣amursoy, İ. Effects of constant time delay procedure on the Halliwick’s method of swimming rotation skills for children with autism. Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2010, 45, 124–135. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, G.; Ippolito, G.; Mazzotta, M.; Sentenza, L.; Muzio, M.R.; Salzano, S.; Conson, M. Effectiveness of a multisystem aquatic therapy for children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1945–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Pan, C. The effect of peer- and sibling-assisted aquatic program on interaction behaviors and aquatic skills of children with autism spectrum disorder and their peers/siblings. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1211–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennis, E. The effects of a physical therapy–directed aquatic program on children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Aquat. Phys. Ther. 2011, 19, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jull, S.; Mirenda, P. Effects of a staff training program on community instructors’ ability to teach swimming skills to children with autism. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2016, 18, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkas, A.; Gökmen, Ö.Z.E.N. Teaching of swimming technique to children with autism: A pilot study. J. Rehabil. Health Disabil. 2015, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, L.M.; D’Adamo, L.; Campbell, K.; Hermreck, B.; Holz, S.; Moxley, J.; Nance, K.; Nolla, M.; Travis, A. A qualitative investigation of swimming experiences of children with autism spectrum disorders and their families. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2019, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.M.; Foster, L.; Harrington, M.; Oxley, C. Effects of a swim program for children with autism spectrum disorder on skills, interest, and participation in swimming. Am. J. Recreat. Ther. 2014, 13, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.M.; Little, L. Feasibility of a swimming intervention to improve sleep behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorder. Ther. Recreat. J. 2017, 51, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, W.; Kondakis, N.; Orr, R.; Warburton, M.; Milne, N. Does hydrotherapy impact behaviours related to mental health and well-being for children with autism spectrum disorder? a randomised crossover-controlled pilot trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriel, K.N.; Kanupka, J.W.; DeLong, K.S.; Noel, K. The impact of aquatic exercise on sleep behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Focus. Autism Other Dev. Disabl. 2016, 31, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.Y. The efficacy of an aquatic program on physical fitness and aquatic skills in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushkarenko, K.; Reid, G.; Smith, V. Effects of enhanced structure in an aquatic’s environment for three boys with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. J. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 22, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Shams-Elden, M. Effect of aquatic exercises approach (Halliwick-therapy) on motor skills for children with autism spectrum disorders. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. Mov. Health 2017, 17, 490–496. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.E. The Effect of Swimming Exercise on Amount and Quality of Sleep for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Bachelor’s Thesis, The University of Akron in Akron, Akron, OH, USA, (Honors Research Projects. 986). April 2019. Available online: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/986 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Yanardag, M.; Akmanoglu, N.; Yilmaz, I. The effectiveness of video prompting on teaching aquatic play skills for children with autism. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanardag, M.; Erkan, M.; Yilmaz, I.; Arıcan, E.; Düzkantar, A. Teaching advance movement exploration skills in water to children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2015, 9, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, I.; Konukman, F.; Birkan, B.; Yanardag, M. Effects of most to least prompting on teaching simple progression swimming skill for children with autism. Educ. Train. Dev. Disabil. 2010, 45, 440–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zanobini, M.; Silvano, S. Effectiveness of the Program “acqua mediatrice di comunicazione” (water as a mediator of communication) on social skills, autistic behaviors and aquatic skills in ASD children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 4134–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrović, M.; Čoh, M.; Daly, D.; Madić, D.; Okičić, T.; Radovanović, D.; Dimitrijević, L.; Hadžović, M.; Jorgić, B.; Bojić, I. Effects of adapted swimming program on orientation in water of children with neuromuscular impairments. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress Youth Sport 2010, Ljubljana, Republika Slovenija, 2–4 December 2010; Kovač, M., Jurak, G., Starc, G., Eds.; Faculty of Sport, University of Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010; pp. 135–140. Available online: http://www.fsp.uni-lj.si/COBISS/Monografije/Proceedings1.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Ilinca, I.; Eugenia, R.; Germina, C.; Ligia, R. Effectiveness of aquatic exercises program to improve the level of physical fitness for children with disabilities. J. Sport Kinet. Mov. 2015, 2, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, B.A.; Oh, D.J. Effects of aquatic exercise on health-related physical fitness, blood fat, and immune functions of children with disabilities. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2018, 14, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriel, K.N.; Marchese, V.G.; Shirk, A.; Wagner, L.; Young, E.; Miller, L. The psychosocial benefits of an inclusive community-based aquatics program. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2012, 24, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.V.S.; Goya, P.S.A.; Ferrari, R.; Durán, M.; Franzini, R.V.; Caromano, F.A.; Favero, F.M.; Oliveira, A.S.B. Comparison of motor function in patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in physical therapy in and out of water: 2-year follow-up. Acta Fisiátrica 2015, 22, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hind, D.; Parkin, J.; Whitworth, V. Aquatic therapy for boys with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD): An external pilot randomized controlled trial. Pilot. Feasibility Stud. 2017, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honório, S.; Batista, M.; Martins, J. The influence of hydrotherapy on obesity prevention in individuals with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2013, 13, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honório, S.; Batista, M.; Paulo, R.; Mendes, P.; Santos, J.; Serrano, J.; Petrica, J.; Mesquita, H.; Faustino, A.; Martins, J. Aquatic influence on mobility of a child with duchenne muscular dystrophy: Case study. Ponte Acad. J. 2016, 72, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santos, C.P.A.; Hengles, R.C.; Cyrillo, F.N.; Rocco, F.M.; Braga, D.M. Aquatic physical therapy in the treatment of a child with merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy: Case report. Acta Fisiatr. 2016, 23, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.M.; Braga, D.M.; Hengles, R.C.; Beas, A.R.V.; Rocco, F.M. The impact of aquatic therapy on the agility of a non-ambulatory patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Fisiatr. 2012, 19, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carew, C.; Des, W.C. Laps or lengths? The effects of different exercise programs on asthma control in children. J. Asthma 2018, 55, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.A.; Fathy, K.A. Ventilatory function response to selected swimming program in hemophilic children. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2015, 83, 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, E.Y.; Salem, M.R.; Ahmed, M.M.; Hagag, A.A. Effect of land training versus aquatic therapy on pulmonary functions and activity tolerance on asthmatic children. Med. J. Cairo Univ. 2016, 84, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Samhan, A.; Mohamed, N.; Elnaggar, R.; Mahmoud, W. Assessment of the clinical effects of aquatic-based exercises in the treatment of children with juvenile dermatomyositis: A 2X2 controlled-crossover trial. Arch. Rheumatol. 2020, 35, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, E.E. The benefits of aerobic aquatic gymnastics on overweight children. Palestrica Third Millenn. Civiliz. Sport 2012, 13, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bayraktar, D.; Savci, S.; Altug-Gucenmez, O.; Manci, E.; Makay, B.; Ilcin, N.; Unsal, E. The effects of 8-week water-running program on exercise capacity in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A controlled trial. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, R.K.; Elshafey, M.A. Effects of combined resistive underwater exercises and interferential current therapy in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 95, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, N.P.; Cares, P.N.; Peñailillo, P.S.M. Effectiveness of Watsu therapy in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. A parallel, randomized, controlled and single-blind clinical trial. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2019, 90, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.K.; Hung, C.L.; Huang, C.J.; Hatfield, B.D.; Hung, T.M. Effects of an aquatic exercise program on inhibitory control in children with ADHD: A preliminary study. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014, 29, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.A.D.; Doyenart, R.; Henrique Salvan, P.; Rodrigues, W.; Felipe Lopes, J.; Gomes, K.; Thirupathi, A.; Pinho, R.A.; Silveira, P.C. Swimming training improves mental health parameters, cognition and motor coordination in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 30, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, S.A.; Osama, S.A.; Azab, A.S.R. Effect of aquatic program therapy on dynamic balance in Down’s syndrome children. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2016, 4, 9938–9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.E.; Sanders, M.E.; Benitez, C.B.; Ortega, A.M. Efficacy of an aquatic exercise program for 3 cases of rett syndrome. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 31, E6–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, J.; Wright, V.; Schmidt, J.; Miller, L.; Lowry, K. Applying the ICF framework to study changes in quality-of-life for youth with chronic conditions. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2011, 14, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Quality of Life Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHO-QOL): Development and general psychometric qualities. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 46, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirte, J.; Van Loey, N.E.E.; Maertens, K.; Moortgat, P.; Hubens, G.; Van Daele, U. Classification of quality of life subscales within the ICF framework in burn research: Identifying overlaps and gaps. Burns 2014, 40, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchan, J.F. Commentary: Where is the person in the ICF? Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2004, 6, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threats, T.; Worrall, L. Response: The ICF is all about the person, and more: A response to Duchan, Simmons-Mackie, Boles, and McLeod. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2004, 6, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyh, S.; Schwegler, U.; Peter, C.; Müller, R. Representing and organizing information to describe the lived experience of health from a personal factors perspective in the light of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF): A discussion paper. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1727–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotkamp, S.; Cibis, W.; Brüggemann, S.; Coenen, M.; Gmünder, H.; Keller, K.; Nüchtern, E.; Schwegler, U.; Seger, W.; Staubli, S. Personal factors classification revisited: A proposal in the light of the biopsychosocial model of the World Health Organization (WHO). Aust. J. Rehab Couns. 2020, 26, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhula, M.; Saukkonen, S.; Xiong, E.; Kinnunen, A.; Heiskanen, T.; Anttila, H. ICF Personal Factors Strengthen Commitment to Person-Centered Rehabilitation—A Scoping Review. Front. Rehabilit. Sci. 2021, 2, 709682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, M.J.; Craddock, G.; Mackeogh, T. The relationship of personal factors and subjective well-being to the use of assistive technology devices. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, J.R.; Shier, M.L. Social work practitioners and subjective well-being: Personal factors that contribute to high levels of subjective well-being. Int. Soc. Work 2010, 53, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; Ziviani, J.; Boyd, R. A systematic review of activities of daily living measures for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2014, 56, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, B.E. Aquatic therapy: Scientific foundations and clinical rehabilitation applications. PM&R 2009, 1, 859–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.D.; Jelsma, J.; Versfeld, P.; Smits-Engelsman, B.C.M. Using the ICF framework to explore the multiple interacting factors associated with developmental coordination disorder. Curr. Dev. Disord. Rep. 2014, 1, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, S.; Okawa, Y. The subjective dimension of functioning and disability: What is it and what is it for? Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorter, J.W.; Currie, S.J. Aquatic exercise programs for children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: What do we know and where do we go? Int. J. Pediatr. 2011, 2001, 712165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, B. The wellbeing benefits of swimming: A systematic review. In The Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Swimming; Cumming, I., Ed.; Swim England’s Swimming and Health Commission: London, UK, 2017; pp. 26–43. Available online: https://www.sportengland.org/media/11765/health-and-wellbeing-benefits-of-swimming-report.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

| and |

|

| The Investigated Diagnosis | CP | ASD | DD | Mus. D | GHC | JIA | ADHD | DCD | Down S. | Rett S. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | 22 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 85 | 76 | 78 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| 68 | 45 | 66 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| 14 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 175 | 125 | 167 | 22 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 18 |

| ICF-CY Component | BF | BS | A&P | EF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Chapters that were used | All eight chapters | Chapters s2, s3, s4, s7 and s8 | All but Chapter 6 | All five chapters |

| 2. The most frequently used chapter (the N. of times its categories have been used) | b7—Neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions (183) | s7—Structures related to movement (14) | d4—Mobility (258) | e3—Support and relationships (16) |

| 3. The most used category (the N. of times it has been used) | b755—Involuntary movement reaction functions (17) | There was no prominent category | d4554—Swimming (21) | e355—Health professionals (10) |

| 4. Health conditions/diagnoses that tested the most of the categories in this component (N. of times) | CP (206) | DD (12) | CP (237) | CP (23) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadar-Frumer, M.; Ten-Napel, H.; Yuste-Sánchez, M.J.; Rodríguez-Costa, I. Feasibility of Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) as a Framework for Aquatic Activities: A Scoping Review. Children 2023, 10, 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121856

Hadar-Frumer M, Ten-Napel H, Yuste-Sánchez MJ, Rodríguez-Costa I. Feasibility of Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) as a Framework for Aquatic Activities: A Scoping Review. Children. 2023; 10(12):1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121856

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadar-Frumer, Merav, Huib Ten-Napel, Maria José Yuste-Sánchez, and Isabel Rodríguez-Costa. 2023. "Feasibility of Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) as a Framework for Aquatic Activities: A Scoping Review" Children 10, no. 12: 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121856

APA StyleHadar-Frumer, M., Ten-Napel, H., Yuste-Sánchez, M. J., & Rodríguez-Costa, I. (2023). Feasibility of Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) as a Framework for Aquatic Activities: A Scoping Review. Children, 10(12), 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10121856