Asserting a Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder with a Complementary Diagnostic Approach: A Brief Report

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

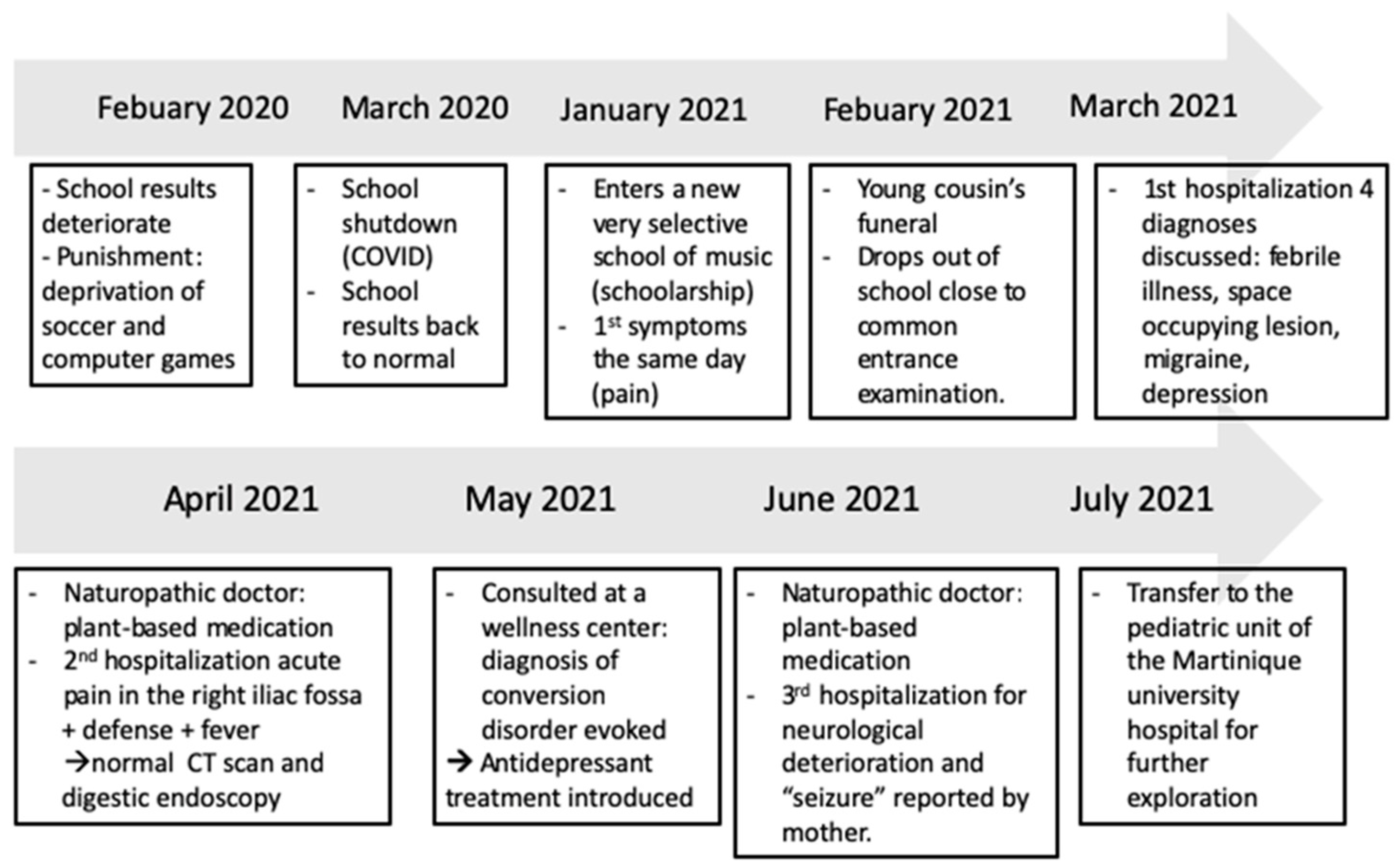

- Patient information

- Clinical findings

- Diagnostic assessment

- Therapeutic Intervention

- Follow-Up and outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- North, C.S. The Classification of Hysteria and Related Disorders: Historical and Phenomenological Considerations. Behav. Sci. 2015, 5, 496–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Malas, N.; Ortiz-Aguayo, R.; Giles, L.; Ibeziako, P. Pediatric Somatic Symptom Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallett, M.; Aybek, S.; Dworetzky, B.A.; McWhirter, L.; Staab, J.; Stone, J. Functional Neurological Disorder: New Phenotypes, Common Mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, D. Mesmer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 2002, 50, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.G.; Bonduelle, M.; Gelfand, T. Charcot: Constructing Neurology, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, N. Les Métamorphoses de L’hystérique; Découverte, L., Ed.; Presse Universitaire: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S.; Breuer, J. Studies on Hysteria; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1893; Available online: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/286589/studies-in-hysteria-by-sigmund-freud-and-joseph-breuer/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Johnson, B. Somatic Symptom Disorders in Children. BMH Med. J-ISSN 2348–392X 2017, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Khundadze, M.; Mkheidze, R.; Geladze, N.; Bakhtadze, S.; Khachapuridze, N. The causes and symptoms of somatoform disorders in children. Georgian Med. News. 2015, 246, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ludot, M.; Merlo, M.; Ibrahim, N.; Piot, M.A.; Lefèvre, H.; Carles, M.E.; Harf, A.; Moro, M.R. “Somatic symptom disorders” in adolescence—A systematic review of the recent literature. L’Encephale 2021, 47, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, E.; Müller, F.; Furaijat, G.; Hillermann, N.; Jablonka, A.; Happle, C.; Simmenroth, A. Does refugee status matter? Medical needs of newly arrived asylum seekers and resettlement refugees—A retrospective observational study of diagnoses in a primary care setting. Confl. Health. 2019, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallin, K.; Lagercrantz, H.; Evers, K.; Engström, I.; Hjern, A.; Petrovic, P. Resignation Syndrome: Catatonia? Culture-Bound? Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, P.; Mariman, A.; Lucza, L.; Sallay, V.; Weiland, A.; Stegers-Jager, K.M.; Vogelaers, D. Epidemiology and organisation of care in medically unexplained symptoms: A systematic review with a focus on cultural diversity and migrants. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowska, K.; Rampersad, R.; Cruz, C.; Shah, U.; Chudleigh, C.; Soe, S.; Gill, D.; Scher, S.; Carrive, P. The respiratory control of carbon dioxide in children and adolescents referred for treatment of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017, 26, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehna, T.; Hanif, R.; e Laila, U.; Ali, S.Z. Life stress and somatic symptoms among adolescents: Gender as moderator. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2016, 66, 1448–1451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chudleigh, C.; Savage, B.; Cruz, C.; Lim, M.; McClure, G.; Palmer, D.M.; Spooner, C.J.; Kozlowska, K. Use of respiratory rates and heart rate variability in the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with functional somatic symptoms. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2019, 24, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowska, K.; Palmer, D.M.; Brown, K.J.; McLean, L.; Scher, S.; Gevirtz, R.; Chudleigh, C.; Catherine, D.C.; Williams, L.M. Reduction of autonomic regulation in children and adolescents with conversion disorders. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 77, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowska, K.; Palmer, D.M.; Brown, K.J.; Scher, S.; Chudleigh, C.; Davies, F.; Williams, L.M. Conversion disorder in children and adolescents: A disorder of cognitive control. J. Neuropsychol. 2015, 9, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simas, C.; Munoz, N.; Arregoces, L.; Larson, H.J. HPV vaccine confidence and cases of mass psychogenic illness following immunization in Carmen de Bolivar, Colombia. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobian, A.D.; Elliott, L. A review of functional neurological symptom disorder etiology and the integrated etiological summary model. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. JPN 2019, 44, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, F.A.; Allcott-Watson, H.; Hadji-Michael, M.; McAllister, E.; Stark, D.; Reilly, C.; Bennett, S.D.; McWillliams, A.; Heyman, I. Cognitive-behavioural treatment of functional neurological symptoms (conversion disorder) in children and adolescents: A case series. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2019, 23, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, V.; Oakley, D.A.; Halligan, P.W.; Deeley, Q. Dissociation in hysteria and hypnosis: Evidence from cognitive neuroscience. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2011, 82, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeley, Q. Hypnosis as a model of functional neurologic disorders. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2016, 139, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuilleumier, P. Brain circuits implicated in psychogenic paralysis in conversion disorders and hypnosis. Neurophysiol. Clin. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 44, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Chastenet, A.M.J. (1751–1825; marquis de) A du texte. Mémoires Pour Servir à l’histoire et à L’établissement du Magnétisme Animal. 1820. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6460832j (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Lacocque, A. Le Complexe de Jonas; Presse universitaire, CERF: Cerf Island, Seychelles, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Fromm, E. The Forgotten Language: An Introduction to the Understanding of Dreams, Fairy Tailes and Myths; Henry Holt & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1951; Available online: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/156968 (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- More, J. The Prophet Jonah: The Story of an Intrapsychic process. Am. Imago. 1970, 27, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H.; Maslow, B.G.; Geiger, H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature, 1st ed.; Penguin/Arkana: Baxter County, AR, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux, G. Ethnopsychoanalysis: Psychoanalysis and Anthropology as Complementary Frames of Reference; University of California Press: Merced, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Guessoum, S.B.; Benoit, L.; Minassian, S.; Mallet, J.; Moro, M.R. Clinical Lycanthropy, Neurobiology, Culture: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 718101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.; Moro, M.R.; Benoit, L. Is early management of psychosis designed for migrants? Improving transcultural variable collection when measuring duration of untreated psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J. Fibromyalgia: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Time | Drug | Dose | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 January | 1 week | Paracetamol | 500 mg/6 h | Pain |

| 6 April | 1 week | Moringa (among others) | ||

| 19 May | 2 months | Fluoxetine | 20 mg/d | Depression |

| 1 June | 1 week | GABA, Melatonin, digestive enzymes, acidophilus, and mentat | ||

| 21 June + 9 August | 1 day | Clonazepam | 1 mg IR | “Seizure” |

| 26 July | 3 weeks | Clonazepam | 9 drops/6 h | Post lumbar puncture syndrome |

| 26 July | 3 weeks | Hydroxyzine | 75 mg/d | Post lumbar puncture syndrome |

| 26 July | 3 weeks | Amitriptyline | 30 mg/day | Post lumbar puncture syndrome |

| 9 August | 3 weeks | Levetiracetam | 750 mg/day | “Seizure” |

| 16 August | 3 weeks | Risperidone | 1 mg/day | Delusions |

| 25 August | 3 weeks | Diazepam | 15 mg/day | “Seizure” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogrizek, A.; Ros, T.; Ludot, M.; Moro, M.-R.; Hatchuel, Y.; Gomez, N.G.; Radjack, R.; Felix, A. Asserting a Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder with a Complementary Diagnostic Approach: A Brief Report. Children 2023, 10, 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101601

Ogrizek A, Ros T, Ludot M, Moro M-R, Hatchuel Y, Gomez NG, Radjack R, Felix A. Asserting a Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder with a Complementary Diagnostic Approach: A Brief Report. Children. 2023; 10(10):1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101601

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgrizek, Anais, Thomas Ros, Maude Ludot, Marie-Rose Moro, Yves Hatchuel, Nicolas Garofalo Gomez, Rahmeth Radjack, and Arthur Felix. 2023. "Asserting a Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder with a Complementary Diagnostic Approach: A Brief Report" Children 10, no. 10: 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101601

APA StyleOgrizek, A., Ros, T., Ludot, M., Moro, M.-R., Hatchuel, Y., Gomez, N. G., Radjack, R., & Felix, A. (2023). Asserting a Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder with a Complementary Diagnostic Approach: A Brief Report. Children, 10(10), 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101601