Bladder Neoplasia in Pediatric Patients—A Single-Center Experience Including a Case Series

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

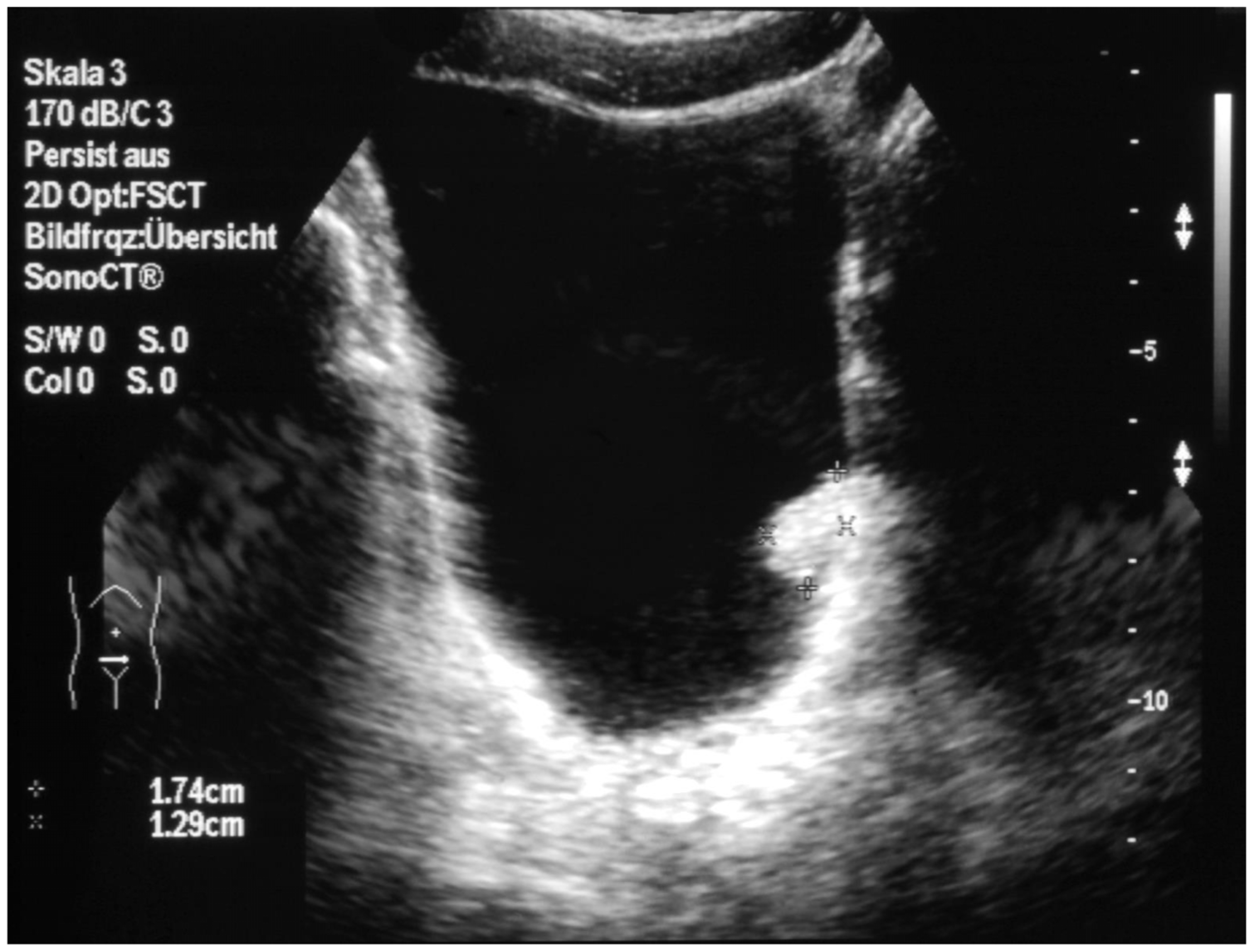

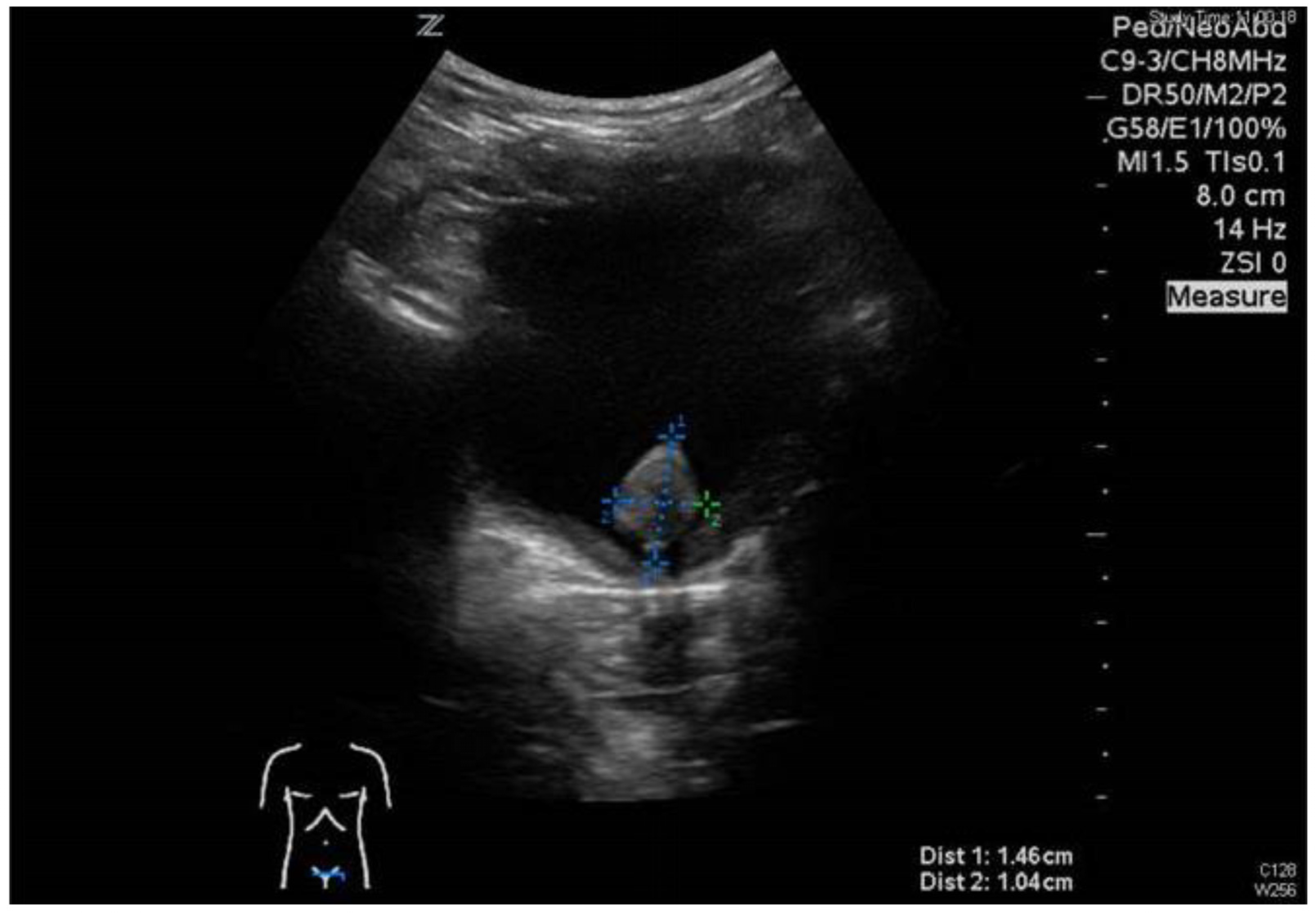

3.1. Patient No. 1

3.2. Patient No. 2

4. Discussion

5. Papillary Urothelial Neoplasia of Low Malignant Potential (PUNLMP)

6. Fibroepithelial Polyp (FEP)

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lezama-del Valle, P.; Jerkins, G.R.; Rao, B.N.; Santana, V.M.; Fuller, C.; Merchant, T.E. Aggressive bladder carcinoma in a child. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2004, 43, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, S.W.; Humphrey, P.A.; Dehner, L.P.; Amin, M.B.; Epstein, J.I. Urothelial neoplasms in patients 20 years or younger: A clinicopathological analysis using the world health organization 2004 bladder consensus classification. J. Urol. 2005, 174, 1967–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demircan, M.; Ceran, C.; Karaman, A.; Uguralp, S.; Mizrak, B. Urethral polyps in children: A review of the literature and report of two cases. Int. J. Urol. 2006, 13, 841–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Goebel, J.; Pacheco, M.R.; Sheldon, C. Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential in a pediatric renal transplant recipient (PUNLMP): A case report. Pediatr. Transplant. 2007, 11, 680–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lall, A.; Webb, N.J.A.; Dickson, A. Episodic painless hematuria of unusual etiology—A case report and review of literature. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2007, 42, 1460–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsheh, A.; Prat, O.; Shenfeld, O.Z.; Reinus, C.; Chertin, B. Fibroepithelial polyp of the bladder neck in children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2008, 24, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eziyi, A.K.; Helmy, T.E.; Sarhan, O.M.; Eissa, W.M.; Ghaly, M.A. Management of male urethral polyps in children: Experience with four cases. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2009, 6, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerena, J.; Krauel, L.; Garcia-Aparicio, L.; Vallasciani, S.; Sunol, M.; Rodo, J. Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder in children and adolescents: Six-case series and review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2010, 6, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, P.; Manchanda, V.; Mohta, A.; Gupta, C.R.; Das, P.; Srivastav, S. Urothelial polyps from anterior urethra in a prepubertal female child: A rare entity. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2012, 47, e13–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, M.; Winiker, H.; Aebersold Keller, F.; Caduff, J. Akuter Harnverhalt bei einem 3-jährigen Jungen mit Phimose. Monatschr. Kinderheilkd. 2013, 161, 786–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, A.; Khorramirouz, R.; Kajbafzadeh, A.M. Congenital urethral polyps in children: Report of 18 patients and review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 835–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apoznanski, W.; Rysiakiewicz, J.; Polok, M.; Rysiakiewicz, K.; Siekanowicz, P.; Hilger, T.; Zagierski, J.; Hilger, M.; Nowak, I.; Koleda, P.; et al. Transurethral resection of the bladder tumour as a treatment method in children with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder—Analysis of our material and literature review. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 24, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrettini, A.; Castagnetti, M.; Salerno, A.; Nappo, S.G.; Manzoni, G.; Rigamonti, W.; Caione, P. Bladder urothelial neoplasms in pediatric age: Experience at three teriary centers. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2015, 11, 26.e1–26.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltsman, J.A.; Malek, M.M.; Reuter, V.E.; Hammond, W.J.; Danzer, E.; Herr, H.W.; LaQuaglia, M.P. Urothelial neoplasms in pediatric and young adult patients: A large single-center series. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurizi, P.; Capozza, M.A.; Triarico, S.; Perrotta, M.L.; Briganti, V.; Ruggiero, A. Relapsed papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) of the young age: A case report and a review of the literature. BMC Urol. 2019, 19, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSharnoby, O.; Fraser, N.; Williams, A.; Scriven, S.; Shenoy, M. Bladder urothelial cell carcinoma as a rare cause of haematuria in children: Our experience and review of current literature. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanee, S.; Shukla, A.R. Bladder malignancies in children aged <18 years: Results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. BJU Int. 2010, 106, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, T.D.; Cheng, L. Papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant potential: Evolving terminology and concepts. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 1995–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, P.A.; Moch, H.; Cubilla, A.L.; Ulbright, T.M.; Reuter, V.E. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, H.; Miller, J.S.; Fajardo, D.A.; Lee, T.K.; Netto, G.J.; Epstein, J. Non-invasive papillary urothelial neoplasms: The 2004 WHO/ISUP classification system. Pathol. Int. 2010, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.L.; Chaux, A.; Karram, S.; Miyamoto, H.; Miller, J.S.; Fajardo, D.A.; Epstein, J.I.; Netto, G.J. Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential of the bladder: Clinicopathologic and outcome analysis from a single academic center. Hum. Pathol. 2011, 42, 1799–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, S.R.; Wang, M.; Montironi, R.; Eble, J.N.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Zhang, S.; Fan, R.; Wang, L.; Osunkoya, A.O.; Koch, M.O.; et al. Molecular characteristics of urothelial neoplasms in children and young adults: A subset of tumors from young patients harbors chromosomal abnormalities but not FGFR3 or TP53 gene mutations. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, M.R.; Ahmadnia, H. P53 overexpression in bladder urothelial neoplasms: New aspect on World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology classification. Urol. J. 2007, 4, 230–233. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, P.J.; Giedl, J.; Stoehr, R.; Junker, K.; Boehm, S.; van Oers, J.M.; Zwarthoff, E.C.; Blaszyk, H.; Fine, S.W.; Humphrey, P.A.; et al. Genomic aberrations are rare in urothelial neoplasms of patients 19 years or younger. J. Pathol. 2007, 211, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritschler, S.; Zaak, D.; Knuechel, R.; Stief, C.G. urine cytology and urine markers—Significance for clinical practice. Urologe 2006, 45, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, G.V.; Bochner, B.H.; Vickers, A.; Teper, E.; Lin, O.; Donat, S.M.; Herr, H.; Dalbagni, G. Association between urinary cytology and pathology for transitional cell malignancies of the urinary tract. J. Urol. 2006, 175, 2038–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaak, D.; Karl, A.; Stepp, H.; Trischler, S.; Tilki, D.; Burger, M.; Knuechel, R.; Stief, C. Fluorescence cystoscopy at bladder cancer, Present trials. Urologe 2007, 46, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haecker, F.-M.; Bruder, E. Bladder Neoplasia in Pediatric Patients—A Single-Center Experience Including a Case Series. Children 2023, 10, 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101596

Haecker F-M, Bruder E. Bladder Neoplasia in Pediatric Patients—A Single-Center Experience Including a Case Series. Children. 2023; 10(10):1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101596

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaecker, Frank-Martin, and Elisabeth Bruder. 2023. "Bladder Neoplasia in Pediatric Patients—A Single-Center Experience Including a Case Series" Children 10, no. 10: 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101596

APA StyleHaecker, F.-M., & Bruder, E. (2023). Bladder Neoplasia in Pediatric Patients—A Single-Center Experience Including a Case Series. Children, 10(10), 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10101596