Involving Children in Health Literacy Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

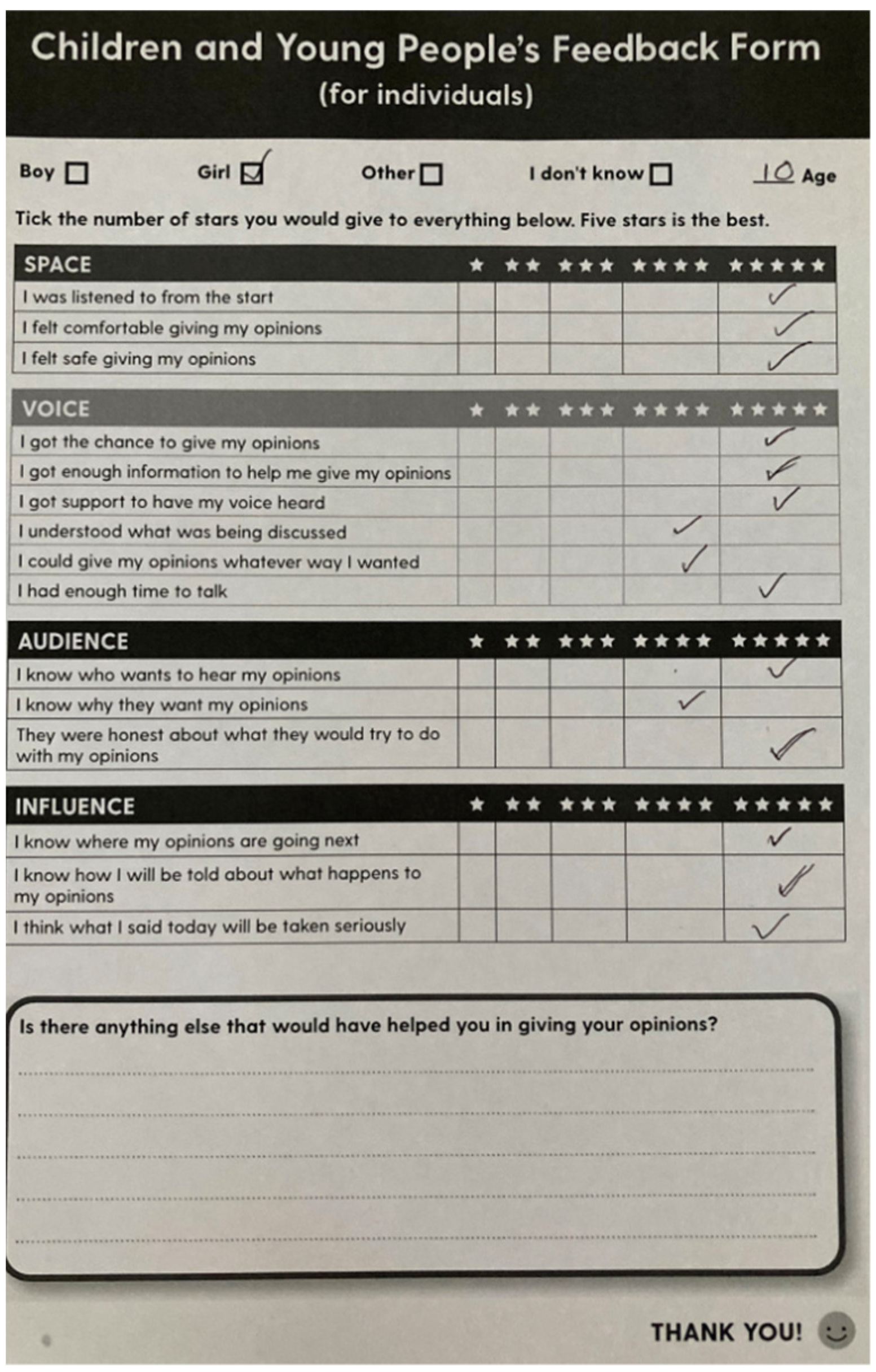

2. Consulting a Children’s Advisory Group to Involve and Engage Children in Health Literacy Research

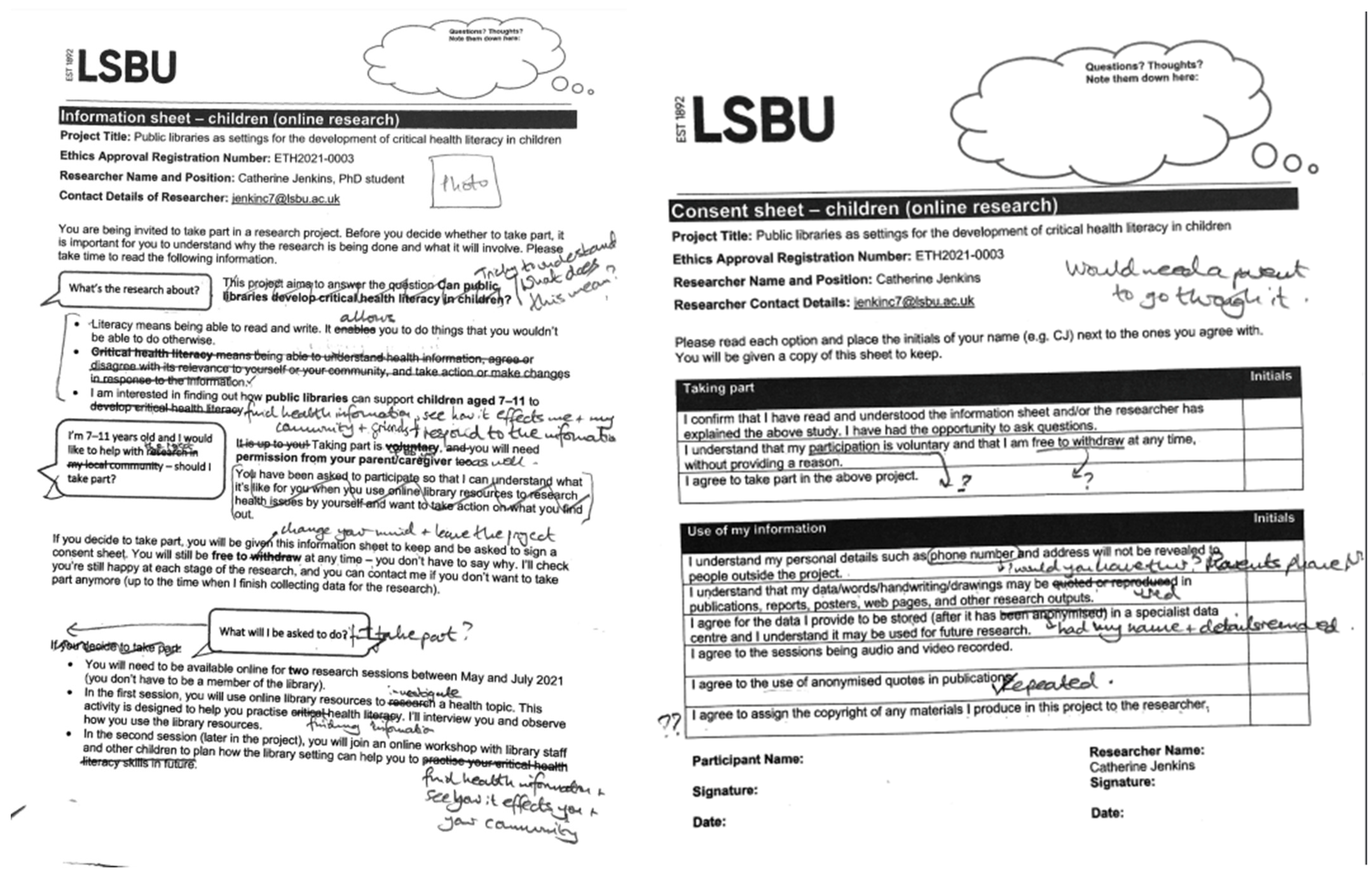

2.1. Ethics, Recruitment, and Structure of Consultations

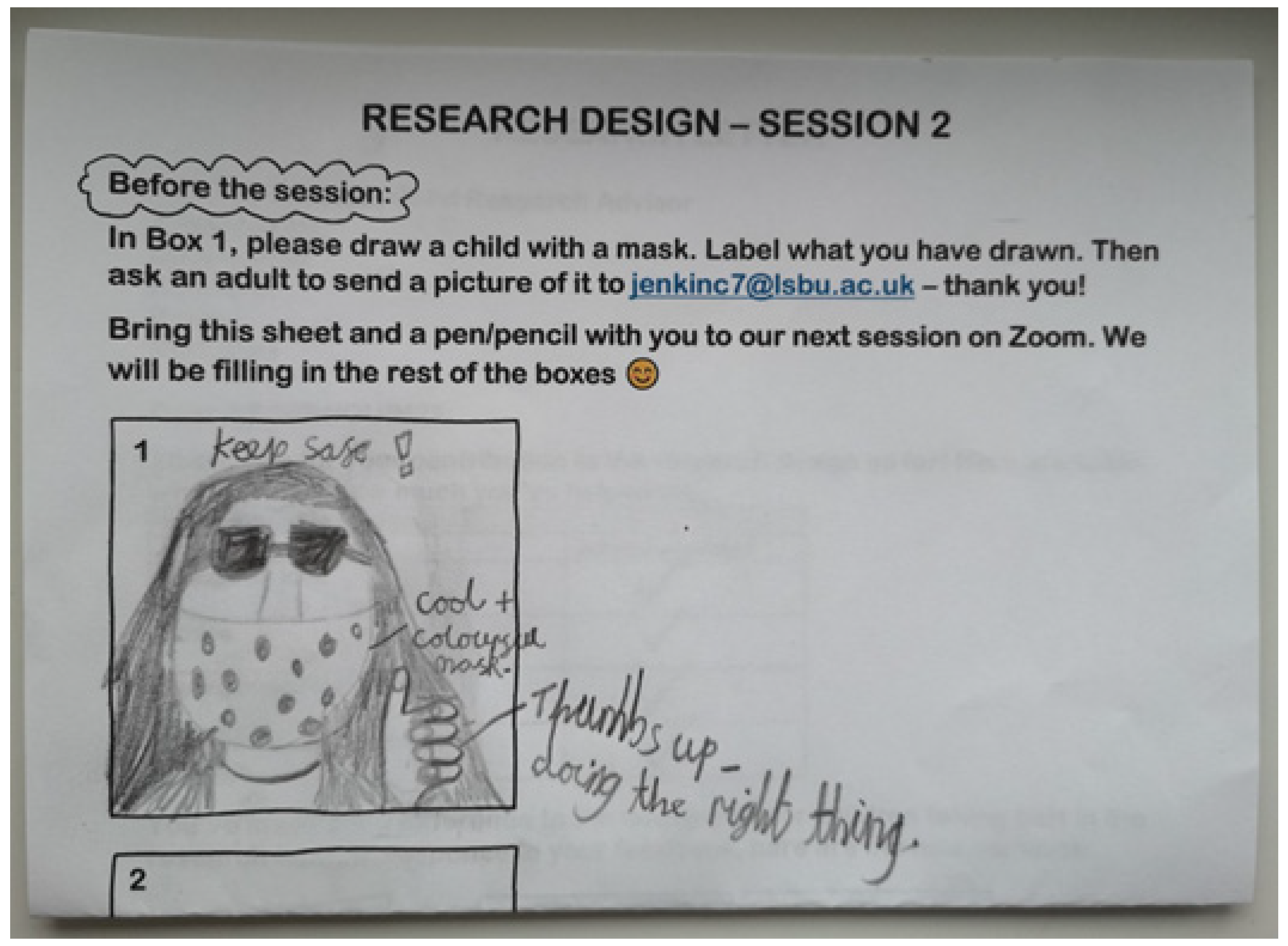

2.2. Listening to and Applying Children’s Methodological Contributions

3. Insights from Consulting a Children’s Advisory Group

3.1. Safeguarding Children’s Involvement and Engagement in Health Literacy Research

I’m pretty sure my mum did that. I don’t remember doing it.(Jar Jar Binks)

Catherine said any questions!(White Hole, to parent)

You’re going to have your work cut out here.(Parent, to Catherine [the researcher])

For homeschooling, they’ve not been allowed to type stuff in chat […] [to Tigerlilly] you might type opinions in chat mightn’t you rather than saying them?(Parent)

[Tigerlilly whispers in Parent’s ear]

Yeah, so it might be, so it’d be good if Catherine can make this feel like not school.(Parent)

Wait, was does critical mean again?(White Hole)

[…]

What’s the word again? It’s the word that that tells you questioning if it’s real, or not.(White Hole)

Okay, so she [Tigerlilly] thinks it sounds like it will be really useful, but they still don’t quite absolutely understand what it will, what that what it would look like.(Parent)

the critical bit.(Tigerlilly)

3.2. Consulting as Part of a Collective Is Valued by Children

Only thing I would say is I wish we could be there together.(ASDPENGUIN22)

I’d like to see the other people.(Jar Jar Binks)

Include like what we’ve thought of, stuff we’ve come up with.(KSI)

3.3. Methods That Work for Facilitating Children’s Participation in the Health Literacy Research Process

cos then you can design it like, if they [adult researchers] designed it might be something like, it likes reading books. But you wanted yours to be, like, not doing that.(Tigerlilly)

It’s like explaining to someone that’s not educated. And I think that if there’s an alien in there, it makes the story more interesting.(ASDPENGUIN22)

3.4. Challenges in Equity-Focused Research with Children

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samerski, S. Health literacy as a social practice: Social and empirical dimensions of knowledge on health and healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 226, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Health Literacy Development for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Volume 1: Overview; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. 2022. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/364203 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Bánfai-Csonka, H.; Betlehem, J.; Deutsch, K.; Derzsi-Horváth, M.; Bánfai, B.; Fináncz, J.; Podráczky, J.; Csima, M. Health literacy in early childhood: A systematic review of empirical studies. Children 2022, 9, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, M.S.M.; Wong, T.K.S. What does health literacy mean to children? Contemp. Nurse 2002, 13, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Bruland, D.; Schlupp, S.; Bollweg, T.M.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; Bond, E.; Sørensen, K.; Bitzer, E.-M.; et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: A systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maindal, H.T.; Aagaard-Hansen, J. Health literacy meets the life-course perspective: Towards a conceptual framework. Glob. Health Action 2020, 13, 1775063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsangi, A.; Semakula, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Austvoll-Dahlgren, A.; Oxman, M.; Rosenbaum, S.; Morelli, A.; Glenton, C.; Lewin, S.; Kaseje, M.; et al. Effects of the Informed Health Choices primary school intervention on the ability of children in Uganda to assess the reliability of claims about treatment effects: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, K.; Howard, D.E.; Aldoory, L. The relationship between health literacy and health conceptualizations: An exploratory study of elementary school-aged children. Health Commun. 2018, 33, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papen, U. Literacy, learning and health: A social practices view of health literacy. Lit. Numer. Stud. 2009, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velardo, S.; Drummond, M. Emphasizing the child in child health literacy research. J. Child Health Care 2017, 21, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilstadius, M.; Gericke, N. Defining contagion literacy: A Delphi study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 2261–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Schlupp, S.; Pinheiro, P. Advancing perspectives on health literacy in childhood and youth. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 35, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otten, C.E.; Moltow, D.; Kemp, N.; Nash, R.E. The imperative to develop health literacy: An ethical evaluation of HealthLit4Kids. J. Child Health Care 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paakkari, L.; George, S. Ethical underpinnings for the development of health literacy in schools: Ethical premises (‘why’), orientations (‘what’) and tone (‘how’). BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbrother, H.; Curtis, P.; Goyder, E. Making health information meaningful: Children’s health literacy practices. SSM—Popul. Health 2016, 2, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fage-Butler, A.M. Challenging violence against women: A Scottish critical health literacy initiative. Health Promot. Int. 2019, 34, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwig, M.; Tiberg, I.; Hallström, I. Elucidating the child’s perspective in health promotion: Children’s experiences of child-centred health dialogue in Sweden. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 36, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, S.; Wills, J. Critical health literacy for the marginalised: Empirical findings. In International Handbook of Health Literacy: Research, Practice and Policy Across the Lifespan; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, H.; Curtis, P.; Kirkcaldy, A. Children’s learning from a Smokefree Sports programme: Implications for health education. Health Educ. J. 2020, 79, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.P.; Auld, M.E. Is further research on the Newest Vital Sign in children necessary? Health Lit. Res. Pr. 2019, 3, e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, L.; Carter, B.; Blake, L.; Saron, H.; Kirton, J.A.; Robichaud, F.; Avila, M.; Ford, K.; Nafria, B.; Forsner, M.; et al. “People play it down and tell me it can’t kill people, but I know people are dying each day”. Children’s health literacy relating to a global pandemic (COVID-19): An international cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Spencer, G.; Curtis, P. Children’s perspectives and experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic and UK public health measures. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccarella, L.; Guo, S. A health equity implementation approach to child health literacy interventions. Children 2022, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, C.L.; Sykes, S.; Wills, J. Public libraries as supportive environments for children’s development of critical health literacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.E. Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-7591-0502-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mullan, K. A Child’s Day: A Comprehensive Analysis of Children’s Time Use in the UK; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-5292-0169-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gaches, S.; Gallagher, M. Children as research consultants: The ethics and rights of no research about them. In The Routledge International Handbook of Young Children’s Rights; Murray, J., Swadener, B.B., Smith, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 484–503. [Google Scholar]

- Bisaillon, L.; Rankin, J. Navigating the politics of fieldwork using institutional ethnography: Strategies for practice. Forum Qual. Soz./Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 2013, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, E.; Rawlings, V. Children as active participants in health literacy research and practice? From rhetoric to rights. In International Handbook of Health Literacy: Research, Practice and Policy Across the Lifespan; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 587–600. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhalovskiy, E.; Armstrong, P.; Armstrong, H.; Bourgeault, I.; Choiniere, J.; Lexchin, J.; Peters, S.; White, J. Qualitative research and the politics of knowledge in an age of evidence: Developing a research-based practice of immanent critique. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannion, G. Going spatial, going relational: Why ‘listening to children’ and children’s participation needs reframing. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2007, 28, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, G.; Fairbrother, H.; Thompson, J. Privileges of power: Authenticity, representation and the ‘problem’ of children’s voices in qualitative health research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facca, D.; Gladstone, B.; Teachman, G. Working the limits of “giving voice” to children: A critical conceptual review. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderbäck, M.; Coyne, I.; Harder, M. The importance of including both a child perspective and the child’s perspective within health care settings to provide truly child-centred care. J. Child Health Care 2011, 15, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.C. Antiracism discourse: The ideological circle in a child world. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2003, 30, 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tegtmejer, T.; Hjörne, E.; Säljö, R. Diagnoses and special educational support. A study of institutional decision-making of provision of special educational support for children at school. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stooke, R.; McKenzie, P.J. Leisure and work in library and community programs for very young children. Libr. Trends 2009, 57, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.L.; Lingard, L.; Hibbert, K.; Regan, S.; Phelan, S.; Stooke, R.; Meston, C.; Schryer, C.; Manamperi, M.; Friesen, F. Supporting children with disabilities at school: Implications for the advocate role in professional practice and education. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 2282–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, A.C.E. When texts become action. The institutional circuit of early childhood intervention. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 25, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, N.; Campbell, M. A child’s death: Lessons from health care providers’ texts. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2003, 30, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Canas, E.; Wathen, N.; Berman, H.; Reaume-Zimmer, P.; Iyer, S.N. Our roles are not at ease: The work of engaging a youth advisory council in a mental health services delivery organization. Health Expect 2021, 24, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, N.; Braimoh, J. Community safety, housing precariousness and processes of exclusion: An institutional ethnography from the standpoints of youth in an ‘unsafe’ urban neighbourhood. Crit. Sociol. 2018, 44, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.S. Vanskelige Forbindelser: En Institutionel Etnografi Om Børns Bevægelse Fra Børnehave Til Skole Difficult Connections. An Institutional Ethnography About Children’s Movement from Kindergarten to Elementary School. Ph.D. Thesis, Danmarks Pædagogiske Universitet, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. Available online: https://www.ucviden.dk/da/publications/vanskelige-forbindelser-en-institutionel-etnografi-om-b%C3%B8rns-bev%C3%A6g (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Balter, A.-S.; Feltham, L.E.; Parekh, G.; Douglas, P.; Underwood, K.; Van Rhijn, T. Re-imagining inclusion through the lens of disabled childhoods. SI 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C. Investigating homework as a family practice in Canada: The capital needed. Education 3-13 2021, 50, 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murru, S. “The Homework House”: Exploring the Social Organisation of Shared Physical Custody in Italy. Exploring the Potential of Institutional Ethnography. Experiences, Reflections and New Pathways from and for the European Context. University of Antwerp. 2021. Available online: https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal:260081 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Murru, S. A Reflexive Analysis on the Use of Social Spatial Network Games (SSNG) and Pictures for Institutional Ethnography: The Case of Children Living Under Shared Custody Agreements; Toronto. 2018. Available online: https://dial.uclouvain.be/pr/boreal/object/boreal:215565 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- INVOLVE Briefing Notes for Researchers: Involving the Public in NHS, Public Health and Social Care Research; INVOLVE: Eastleigh. 2012. Available online: http://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/INVOLVEBriefingNotesApr2012.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- NIHR Involving Children and Young People as Advisors in Research. Learning for Involvement. 2021. Available online: https://www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/?opportunity=nihr-involving-children-and-young-people-as-advisors-in-research (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Pinter, A.; Zandian, S. ‘I thought it would be tiny little one phrase that we said, in a huge big pile of papers’: Children’s reflections on their involvement in participatory research. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidonde, J.; Vanstone, M.; Schwartz, L.; Abelson, J. An institutional ethnographic analysis of public and patient engagement activities at a national health technology assessment agency. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2021, 37, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.M.; Jamieson, L.; Wright, L.H.V.; Rizzini, I.; Mayhew, A.; Narang, J.; Tisdall, E.K.M.; Ruiz-Casares, M. Involving child and youth advisors in academic research about child participation: The Child and Youth Advisory Committees of the International and Canadian Child Rights Partnership. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 109, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, F.; Saunders, C.; Elmer, A.; Badger, S. ‘A group of totally awesome people who do stuff’—A qualitative descriptive study of a children and young people’s patient and public involvement endeavour. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, M. Children as researchers: What we can learn from them about the impact of poverty on literacy opportunities? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2009, 13, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, M.; Forrest, R.; Dent, N.; Ward, S. ‘Just teach us the skills please, we’ll do the rest’: Empowering ten-year-olds as active researchers. Child. Soc. 2004, 18, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouncefield-Swales, A.; Harris, J.; Carter, B.; Bray, L.; Bewley, T.; Martin, R. Children and young people’s contributions to public involvement and engagement activities in health-related research: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Rights Coalition Asia; ChildFund Korea Child Participation Guidelines on Online Discussions with Children. 2021. Available online: https://www.crcasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Child-Participation-Guidelines-on-Online-Discussions-with-Children-CRC-Asia-2021.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Pothong, K.; Livingstone, S. Navigating the Ethical Challenges of Consulting Children Via Zoom. 5Rights|Digital Futures Commision. 2021. Available online: https://digitalfuturescommission.org.uk/blog/navigating-the-ethical-challenges-of-consulting-children-via-zoom/ (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Bammer, G. Stakeholder Engagement in Research: The Research-Modified IAP2 Spectrum. Available online: https://i2insights.org/2020/01/07/research-modified-iap2-spectrum/ (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Chan, W.; Thurairajah, P.; Butcher, N.; Oosterwijk, C.; Wever, K.; Eichler, I.; Thompson, C.; Junker, A.; Offringa, M.; Preston, J. Guidance on development and operation of Young Persons’ Advisory Groups. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simovska, V.; Jensen, B.B. Conceptualizing Participation—The health of Children and Young People. In A Report Prepared for the European Commission Conference on Youth Health, Brussels, Belgium, 9–10 July 2009; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kalnins, I.; McQueen, D.V.; Backett, K.C.; Curtice, L.; Currie, C.E. Children, empowerment and health promotion: Some new directions in research and practice. Health Promot. Int. 1992, 7, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, D. The case for catalytic validity: Building health and safety through knowledge transfer. Policy Pract. Health Saf. 2007, 5, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Literacy in the Context of Health, Well-Being and Learning Outcomes—The Case of Children and Adolescents in Schools. Concept Paper; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344901 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Jensen, B.B. Environmental and health education viewed from an action-oriented perspective: A case from Denmark. J. Curric. Stud. 2004, 36, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessnack, M. Draw-and-tell conversations with children about fear. Qual. Health Res. 2006, 16, 1414–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartel, J. Draw-and-Write Techniques. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: http://www.jennahartel.info/uploads/8/3/3/8/8338986/draw-and-write_techniques.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Horstman, M.; Aldiss, S.; Richardson, A.; Gibson, F. Methodological issues when using the draw and write technique with children aged 6 to 12 years. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backett-Milburn, K.; McKie, L. A critical appraisal of the draw and write technique. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolini, D. Articulating practice through the Interview to the Double. Manag. Learn. 2009, 40, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, A. Following the red thread of information in information literacy research: Recovering local knowledge through Interview to the Double. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2014, 36, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, D.W.; Smith, D.E.; Smith, W. Manufacturing Meltdown: Reshaping Steel Work; Fernwood Pub: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2011; ISBN 978-1-55266-402-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tartari, M. Reflexivity, responsibilities, and self: Analyzing the legal transition from double to single parenthood and suggesting changes in policy. Paper presented at SSSP Annual Meeting. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dieumegard, G.; Cunningham, E. The implementation of participatory approaches in interviews involving adolescents. In Proceedings of the 18th Biennial EARLI Conference for Research on Learning and Instruction; RWTH Aachen: Aachen, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02069092 (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Lundy, L. Involving children in decision-making: The Lundy Model. Sharing Good Practice to Make a Difference, North East and North Cumbria’s Child Health and Wellbeing Network Huddle. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lundy, L.; Hub na nÓg. Participation Framework. Hub na nÓg: Young Voices in Decision Making. 2021. Available online: https://hubnanog.ie/participation-framework/ (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Lima, L.; Lemos, M.S. de The importance of the instructions in the use of draw-and-write techniques for understanding children’s health and illness concepts. Psychol. Community Health 2014, 3, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abel, T.; Benkert, R. Critical health literacy: Reflection and action for health. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daac114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, L.; Appleton, V.; Sharpe, A. ‘If I knew what was going to happen, it wouldn’t worry me so much’: Children’s, parents’ and health professionals’ perspectives on information for children undergoing a procedure. J. Child Health Care 2019, 23, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medforth, N. “Our Unified Voice to Implement Change and Advance the View of Young Carers and Young Adult Carers.” An Appreciative Evaluation of the Impact of a National Young Carer Health Champions Programme. Soc. Work Public Health 2022, 37, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, L.; Blake, L.; Protheroe, J.; Nafria, B.; de Avila, M.A.G.; Ångström-Brännström, C.; Forsner, M.; Campbell, S.; Ford, K.; Rullander, A.-C.; et al. Children’s pictures of COVID-19 and measures to mitigate its spread: An international qualitative study. Health Educ. J. 2021, 80, 811–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Mazur, J.; Boberova, Z.; Sudeck, G.; Kalman, M.; Paakkari, O. A comparative study on adolescents’ health literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessnack, M.; Chung, S.; Perkhounkova, E.; Hein, M. Using the “Newest Vital Sign” to assess health literacy in children. J. Pediatric Health Care 2014, 28, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varpio, L.; Ajjawi, R.; Monrouxe, L.V.; O’Brien, B.C.; Rees, C.E. Shedding the cobra effect: Problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med. Educ. 2017, 51, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Child Advisor Pseudonym | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Luna Starshine | 7 | M |

| Jar Jar Binks | 8 | M |

| White Hole | 8 | M |

| ASDPENGUIN22 | 9 | F |

| Ronaldo | 9 | M |

| KSI | 10 | M |

| Tigerlilly | 10 | F |

| Willowshot Ebony | 11 | F |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jenkins, C.L.; Wills, J.; Sykes, S. Involving Children in Health Literacy Research. Children 2023, 10, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010023

Jenkins CL, Wills J, Sykes S. Involving Children in Health Literacy Research. Children. 2023; 10(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleJenkins, Catherine L., Jane Wills, and Susie Sykes. 2023. "Involving Children in Health Literacy Research" Children 10, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010023

APA StyleJenkins, C. L., Wills, J., & Sykes, S. (2023). Involving Children in Health Literacy Research. Children, 10(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10010023