The Complexity of the Relationship Between Mitral and Aortic Valve Annular Dimensions in the Same Healthy Adults: Detailed Insights from the Three-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiographic MAGYAR-Healthy Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

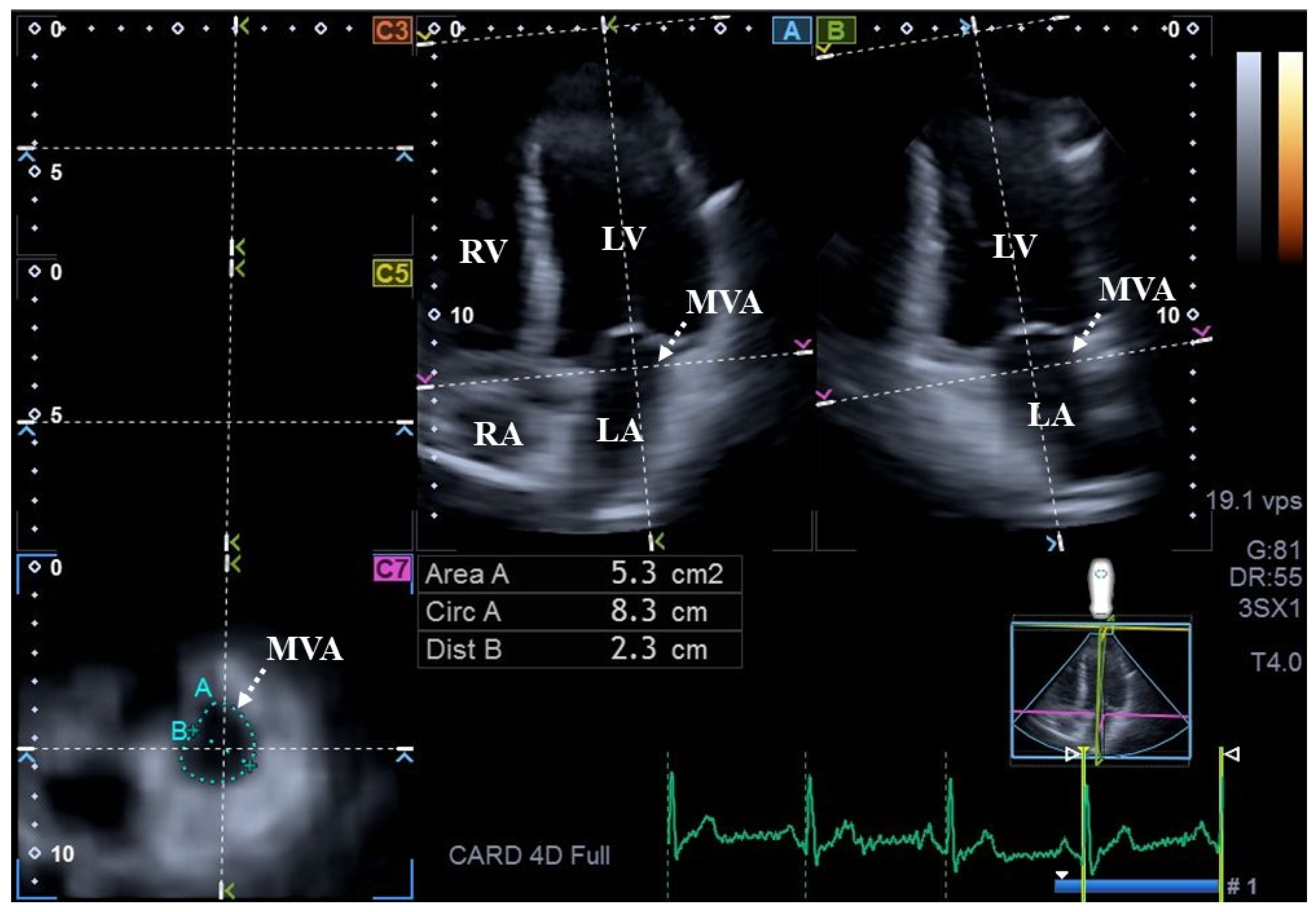

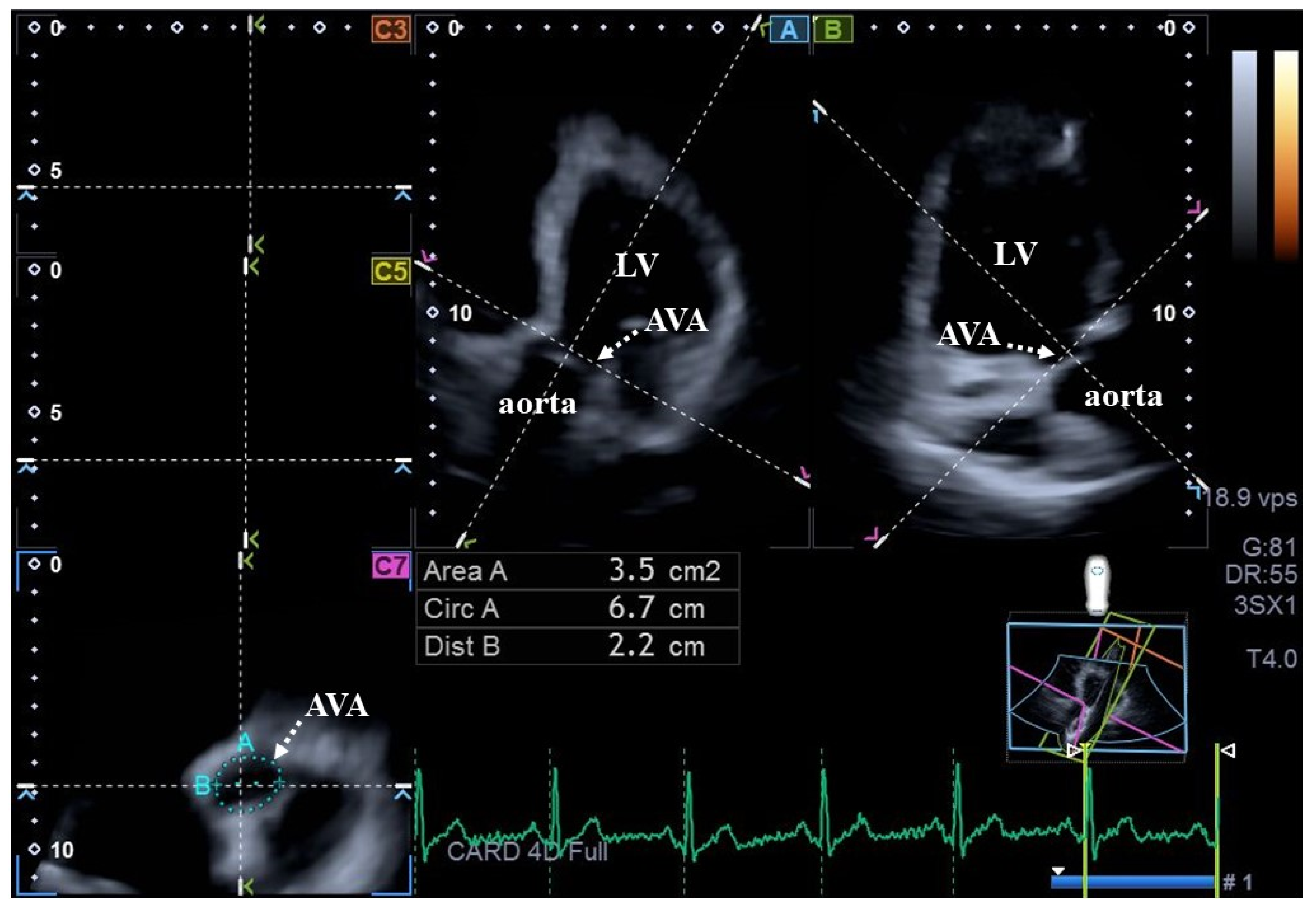

2. Subjects and Methods

3. Results

| Parameters | Measures |

|---|---|

| end-diastolic mitral valve annular diameter (MVA-D-D, cm) | 2.45 ± 0.41 * |

| end-diastolic mitral valve annular area (MVA-A-D, cm2) | 7.39 ± 2.19 * |

| end-diastolic mitral valve annular perimeter (MVA-P-D, cm) | 10.26 ± 1.49 * |

| end-systolic mitral valve annular diameter (MVA-D-S, cm) | 1.61 ± 0.38 * |

| end-systolic mitral valve annular area (MVA-A-S, cm2) | 3.47 ± 1.20 |

| end-systolic mitral valve annular perimeter (MVA-P-S, cm) | 7.11 ± 1.18 * |

| end-diastolic aortic valve annular diameter (AVA-D-D, cm) | 2.00 ± 0.34 |

| end-diastolic aortic valve annular area (AVA-A-D, cm2) | 3.13 ± 0.90 |

| end-diastolic aortic valve annular perimeter (AVA-P-D, cm) | 6.24 ± 0.94 |

| end-systolic aortic valve annular diameter (AVA-D-S, cm) | 2.03 ± 0.32 |

| end-systolic aortic valve annular area (AVA-A-S, cm2) | 3.30 ± 0.89 |

| end-systolic aortic valve annular perimeter (AVA-P-S, cm) | 6.45 ± 0.89 |

| MVA-D-D ≤ 2.01 cm (n = 24) | 2.01 cm < MVA-D-D < 2.86 cm (n = 88) | 2.86 cm ≤ MVA-D-D (n = 22) | MVA-A-D ≤ 5.20 cm2 (n = 21) | 5.20 cm2 < MVA-A-D < 9.58 cm2 (n = 77) | 9.58 cm2 ≤ MVA-A-D (n = 36) | MVA-P-D ≤ 8.77 cm (n = 23) | 8.77 cm < MVA-P-D < 11.75 cm (n = 89) | 11.75 cm ≤ MVA-P-D (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA-D-S (cm) | 1.44 ± 0.29 * | 1.63 ± 0.41 *,† | 1.71 ± 0.30 *,† | 1.43 ± 0.24 * | 1.61 ± 0.39 *,† | 1.72 ± 0.38 *,† | 1.46 ± 0.23 * | 1.59 ± 0.39 * | 1.78 ± 0.37 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-A-S (cm2) | 2.85 ± 0.79 | 3.50 ± 1.24 † | 4.08 ± 1.02 †,‡ | 2.54 ± 0.66 * | 3.46 ± 1.13 † | 4.04 ± 1.24 †,‡ | 2.53 ± 0.62 * | 3.47 ± 1.15 *,† | 4.36 ± 1.09 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-P-S (cm) | 6.64 ± 1.06 | 7.06 ± 1.17 * | 7.86 ± 0.93 *,†,‡ | 6.10 ± 0.92 | 7.12 ± 1.04 *,† | 7.69 ± 1.18 *,†,‡ | 6.06 ± 0.79 | 7.12 ± 1.08 *,† | 8.04 ± 0.99 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-D-D (cm) | 1.90 ± 0.15 | 2.05 ± 0.35 *,† | 3.09 ± 0.19 *,†,‡ | 2.00 ± 0.22 | 2.39 ± 0.33 *,† | 2.84 ± 0.29 *,†,‡ | 2.03 ± 0.20 | 2.43 ± 0.35 *,† | 2.91 ± 0.30 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-A-D (cm2) | 5.09 ±0.98 * | 7.35 ± 1.66 *,† | 10.16 ± 1.81 *,†,‡ | 4.40 ± 0.61 * | 6.92 ± 0.88 *,† | 10.28 ± 1.34 *,†,‡ | 4.47 ± 0.66 * | 7.22 ± 1.18 *,† | 10.88 ± 1.25 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-P-D (cm) | 8.84 ± 1.13 * | 10.28 ± 1.21 *,† | 11.86 ± 1.14 *,†,‡ | 8.07 ± 0.67 * | 10.02 ± 0.59 *,† | 12.17 ± 0.80 *,†,‡ | 8.05 ± 0.58 * | 10.23 ± 0.74 *,† | 12.55 ± 0.70 *,†,‡ |

| AVA-D-S (cm) | 1.98 ± 0.26 | 2.03 ± 0.32 | 2.10 ± 0.34 | 2.11 ± 0.31 | 1.98 ± 0.31 | 2.10 ± 0.32 ‡ | 2.09 ± 0.34 | 1.99 ± 0.30 | 2.12 ± 0.31 |

| AVA-A-S (cm2) | 3.12 ± 0.76 | 3.30 ± 0.90 | 3.56 ± 0.93 | 3.42 ± 0.85 | 3.15 ± 0.88 | 3.58 ± 0.89 ‡ | 3.39 ± 0.94 | 3.19 ± 0.86 | 3.61 ± 0.87 ‡ |

| AVA-P-S (cm) | 6.27 ± 0.76 | 6.46 ± 0.90 | 6.70 ± 0.93 | 6.56 ± 0.77 | 6.30 ± 0.89 | 6.75 ± 0.88 †,‡ | 6.50 ± 0.90 | 6.35 ± 0.86 | 6.79 ± 0.86 ‡ |

| AVA-D-D (cm) | 1.90 ± 0.29 | 2.02 ± 0.33 | 2.05 ± 0.35 | 1.97 ± 0.30 | 1.95 ± 0.34 | 2.12 ± 0.31 ‡ | 1.98 ± 0.31 | 1.97 ± 0.33 | 2.13 ± 0.33 ‡ |

| AVA-A-D (cm2) | 2.88 ± 0.98 | 3.17 ± 0.87 | 3.33 ± 0.88 | 3.17 ± 1.03 | 3.00 ± 0.86 | 3.37 ± 0.82 ‡ | 3.18 ± 1.02 | 3.07 ± 0.90 | 3.41 ± 0.89 |

| AVA-P-D (cm) | 5.77 ± 1.07 | 6.34 ± 0.86 † | 6.49 ± 0.91 † | 6.01 ± 1.18 | 6.17 ± 0.88 | 6.53 ± 0.81 †,‡ | 6.04 ± 1.17 | 6.16 ± 0.95 | 6.58 ± 0.87 ‡ |

| ES-AVA-A > ED-AVA-A (%) | 17 (71) | 51 (58) | 13 (59) | 16 (76) | 42 (55) | 23 (64) | 16 (70) | 50 (56) | 15 (63) |

| MVA-D-S ≤ 1.3 cm (n = 25) | 1.3 cm < MVA-D-S < 1.99 cm (n = 83) | 1.99 cm ≤ MVA-D-S (n = 26) | MVA-A-S ≤ 2.27 cm2 (n = 22) | 2.27 cm2 < MVA-A-S < 4.67 cm2 (n = 90) | 4.67 cm2 ≤ MVA-A-S (n = 22) | MVA-P-S ≤ 5.93 cm (n = 25) | 5.93 cm < MVA-P-S < 8.29 cm (n = 87) | 8.29 cm ≤ MVA-P-S (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA-D-S (cm) | 1.11 ± 0.11 * | 1.58 ± 0.19 *,† | 2.21 ± 0.17 *,†,‡ | 1.21 ± 0.14 * | 1.58 ± 0.31 *,† | 2.12 ± 0.25 †,‡ | 1.22 ± 0.15 * | 1.64 ± 0.33 *,† | 1.91 ± 0.41 †,‡ |

| MVA-A-S (cm2) | 2.32 ± 0.67 * | 3.36 ± 0.88 *,† | 5.03 ± 0.94 *,†,‡ | 1.90 ± 0.18 * | 3.37 ± 0.66 † | 5.47 ± 0.68 *,†,‡ | 2.04 ± 0.44 * | 3.45 ± 0.73 † | 5.14 ± 1.08 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-P-S (cm) | 6.13 ± 1.06 | 7.05 ± 0.96 *,† | 8.32 ± 0.88 *,†,‡ | 5.39 ± 0.34 * | 7.11 ± 0.71 *,† | 8.80 ± 0.68 *,†,‡ | 5.55 ± 0.63 * | 7.14 ± 0.66 *,† | 8.72 ± 0.87 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-D-D (cm) | 2.25 ± 0.38 * | 2.43 ± 0.41 * | 2.72 ± 0.28 *,†,‡ | 2.23 ± 0.29 * | 2.44 ± 0.43 *,† | 2.69 ± 0.29 *,†,‡ | 2.21 ± 0.27 * | 2.46 ± 0.42 *,† | 2.64 ± 0.37 *,† |

| MVA-A-D (cm2) | 6.64 ± 1.93 * | 7.14 ± 2.13 * | 8.98 ± 1.89 *,†,‡ | 6.07 ± 1.76 * | 7.29 ± 2.10 *,† | 9.10 ± 1.83 *,†,‡ | 6.04 ± 1.63 * | 7.33 ± 2.05 *,† | 9.10 ± 2.03 *,†,‡ |

| MVA-P-D (cm) | 9.84 ± 1.35 * | 10.12 ± 1.48 * | 11.17 ± 1.33 *,†,‡ | 9.40 ± 1.33 * | 10.20 ± 1.43 *,† | 11.39 ± 1.18 *,†,‡ | 9.39 ± 1.26 * | 10.20 ± 1.40 *,† | 11.50 ± 1.21 *,†,‡ |

| AVA-D-S (cm) | 2.03 ± 0.35 | 2.04 ± 0.31 | 1.99 ± 0.31 | 1.97 ± 0.36 | 2.04 ± 0.31 | 2.04 ± 0.29 | 1.99 ± 0.33 | 2.01 ± 0.31 | 2.10 ± 0.31 |

| AVA-A-S (cm2) | 3.29 ± 1.06 | 3.31 ± 0.87 | 3.27 ± 0.80 | 3.22 ± 1.03 | 3.29 ± 0.89 | 3.40 ± 0.72 | 3.20 ± 0.95 | 3.26 ± 0.89 | 3.46 ± 0.86 ‡ |

| AVA-P-S (cm) | 6.44 ± 1.03 | 6.47 ± 0.86 | 6.42 ± 0.87 | 6.36 ± 0.99 | 6.44 ± 0.89 | 6.60 ± 0.76 | 6.35 ± 0.92 | 6.40 ± 0.89 | 6.67 ± 0.85 ‡ |

| AVA-D-D (cm) | 2.03 ± 0.36 | 1.99 ± 0.32 | 1.98 ± 0.37 | 1.99 ± 0.32 | 1.97 ± 0.35 | 2.13 ± 0.28 ‡ | 2.01 ± 0.30 | 1.95 ± 0.34 | 2.13 ± 0.33 ‡ |

| AVA-A-D (cm2) | 3.04 ± 1.09 | 3.17 ± 0.81 | 3.06 ± 0.97 | 2.93 ± 1.01 | 3.11 ± 0.87 | 3.40 ± 0.84 | 2.96 ± 0.95 | 3.08 ± 0.86 | 3.41 ± 0.93 |

| AVA-P-D (cm) | 6.20 ± 1.07 | 6.27 ± 0.87 | 6.18 ± 1.03 | 6.09 ± 1.00 | 6.20 ± 0.94 | 6.57 ± 0.82 | 6.14 ± 0.94 | 6.16 ± 0.93 | 6.58 ± 0.91 ‡ |

| ES-AVA > ED-AVA (%) | 18 (72) | 47 (57) | 16 (62) | 18 (82) | 51 (57) | 12 (55) | 19 (76) | 48 (55) | 14 (64) |

| AVA-D-D ≤ 1.66 cm (n = 17) | 1.66 cm < AVA-D-D < 2.34 (n = 89) | 2.34 cm ≤ AVA-D-D (n = 28) | AVA-A-D ≤ 2.23 cm2 (n = 18) | 2.23 cm2 < AVA-A-D < 4.03 cm2 (n = 100) | 4.03 cm2 ≤ AVA-A-D (n = 16) | AVA-P-D ≤ 5.3 cm (n = 17) | 5.3 cm < AVA-P-D < 7.18 cm (n = 100) | 7.18 cm ≤ AVA-P-D (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA-D-S (cm) | 1.77 ± 0.41 | 1.58 ± 0.36 *,† | 1.60 ± 0.39 * | 1.71 ± 0.48 | 1.60 ± 0.36 * | 1.46 ± 0.33 * | 1.74 ± 0.48 | 1.60 ± 0.36 * | 1.54 ± 0.38 * |

| MVA-A-S (cm2) | 3.42 ± 0.96 * | 3.41 ± 1.16 | 3.69 ± 1.37 | 3.32 ± 1.19 * | 3.46 ± 1.15 | 3.58 ± 1.50 * | 3.34 ± 1.15 * | 3.45 ± 1.16 | 3.73 ± 1.45 * |

| MVA-P-S (cm) | 6.72 ± 1.03 * | 7.06 ± 1.13 * | 7.34 ± 1.38 | 6.78 ± 1.17 * | 7.11 ± 1.10 * | 7.32 ± 1.53 | 6.76 ± 1.11 * | 7.11 ± 1.12 * | 7.42 ± 1.47 |

| MVA-D-D (cm) | 2.31 ± 0.41 * | 2.44 ± 0.41 * | 2.55 ± 0.39 | 2.41 ± 0.44 * | 2.44 ± 0.39 * | 2.49 ± 0.44 | 2.38 ± 0.48 * | 2.44 ± 0.39 * | 2.54 ± 0.41 |

| MVA-A-D (cm2) | 7.42 ± 0.99 * | 7.38 ± 2.11 * | 7.88 ± 2.52 * | 7.07 ± 2.33 * | 7.32 ± 2.01 * | 7.88 ± 2.75 * | 7.14 ± 2.59 * | 7.32 ± 2.02 * | 8.05 ± 2.59 * |

| MVA-P-D (cm) | 6.96 ± 0.96 * | 10.27 ± 1.42 * | 10.58 ± 1.71 * | 9.95 ± 1.52 * | 10.23 ± 1.39 * | 10.64 ± 1.86 * | 9.99 ± 1.66 * | 10.24 ± 1.39 * | 10.72 ± 1.76 * |

| AVA-D-S (cm) | 1.68 ± 0.24 | 2.01 ± 0.26 † | 2.31 ± 0.27 †,‡ | 1.67 ± 0.20 | 2.03 ± 0.27 † | 2.41 ± 0.24 †,‡ | 1.74 ± 0.25 | 2.02 ± 0.28 † | 2.37 ± 0.26 †,‡ |

| AVA-A-S (cm2) | 2.39 ± 0.58 | 3.20 ± 0.72 † | 4.18 ± 0.84 †,‡ | 2.26 ± 0.37 | 3.26 ± 0.71 † | 4.60 ± 0.76 †,‡ | 2.34 ± 0.45 | 3.25 ± 0.71 † | 4.55 ± 0.77 †,‡ |

| AVA-P-S (cm) | 5.51 ± 0.66 | 6.37 ± 0.73 † | 7.32 ± 0.72 †,‡ | 5.37 ± 0.48 | 6.44 ± 0.70 † | 7.73 ± 0.59 † | 5.44 ± 0.57 | 6.42 ± 0.71 † | 7.68 ± 0.61 †,‡ |

| AVA-D-D (cm) | 1.44 ± 0.16 | 1.96 ± 0.16 † | 2.47 ± 0.16 †,‡ | 1.54 ± 0.21 | 2.00 ± 0.25 † | 2.47 ± 0.25 †,‡ | 1.55 ± 0.21 | 1.99 ± 0.24 † | 2.49 ± 0.23 †,‡ |

| AVA-A-D (cm2) | 1.95 ± 0.44 | 3.03 ± 0.66 † | 4.17 ± 0.66 †,‡ | 1.82 ± 0.29 | 3.10 ± 0.51 † | 7.43 ± 1.39 †,‡ | 2.01 ± 1.03 | 3.07 ± 0.51 † | 4.62 ± 0.54 †,‡ |

| AVA-P-D (cm) | 4.99 ± 0.57 | 6.13 ± 0.70 † | 7.34 ± 0.55 †,‡ | 4.89 ± 0.49 | 6.29 ± 0.53 † | 12.14 ± 0.54 †,‡ | 4.61 ± 0.69 | 6.27 ± 0.51 † | 7.72 ± 0.42 †,‡ |

| ES-AVA > ED-AVA (%) | 13 (76) | 55 (62) | 13 (46) | 15 (83) | 57 (57) | 9 (56) | 13 (76) | 59 (59) | 9 (53) |

| AVA-D-S ≤ 1.71 cm (n = 25) | 1.71 cm < AVA-D-S < 2.35 cm (n = 89) | 2.35 cm ≤ AVA-D-S (n = 20) | AVA-A-S ≤ 2.41 cm2 (n = 18) | 2.41 cm2 < AVA-A-S < 4.19 cm2 (n = 92) | 4.19 cm2 ≤ AVA-A-S (n = 24) | AVA-P-S ≤ 5.56 cm (n = 19) | 5.56 cm < AVA-P-S < 7.34 cm (n = 93) | 7.34 cm ≤ AVA-P-S (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA-D-S (cm) | 1.59 ± 0.34 | 1.63 ± 0.41 * | 1.55 ± 0.29 * | 1.59 ± 0.34 | 1.63 ± 0.40 * | 1.52 ± 0.32 * | 1.63 ± 0.37 * | 1.63 ± 0.39 * | 1.49 ± 0.33 * |

| MVA-A-S (cm2) | 3.11 ± 1.07 * | 3.60 ± 1.18 * | 3.34 ± 1.35 * | 3.14 ± 1.00 * | 3.56 ± 1.22 * | 3.39 ± 1.23 * | 3.24 ± 1.06 * | 3.52 ± 1.21 * | 3.45 ± 1.28 * |

| MVA-P-S (cm) | 6.67 ± 1.05 * | 7.25 ± 1.13 * | 7.02 ± 1.40 | 6.71 ± 1.02 * | 7.19 ± 1.17 * | 7.10 ± 1.26 * | 6.78 ± 1.05 * | 7.16 ± 1.16 * | 7.18 ± 1.33 |

| MVA-D-D (cm) | 2.44 ± 0.37 * | 2.44 ± 0.40 * | 2.48 ± 0.47 | 2.47 ± 0.40 * | 2.42 ± 0.40 * | 2.53 ± 0.45 | 2.51 ± 0.41 * | 2.40 ± 0.39 * | 2.60 ± 0.43 * |

| MVA-A-D (cm2) | 7.16 ± 1.72 * | 7.55 ± 2.11 * | 6.94 ± 2.86 * | 6.96 ± 1.42 * | 7.47 ± 2.17 * | 7.40 ± 2.66 * | 7.17 ± 1.65 * | 7.36 ± 2.18 * | 7.83 ± 2.54 * |

| MVA-P-D (cm) | 10.18 ± 1.24 * | 10.37 ± 1.44 *,† | 9.92 ± 1.91 * | 9.90 ± 1.07 * | 10.34 ± 1.47 * | 10.27 ± 1.79 * | 10.02 ± 1.15 * | 10.26 ± 1.51 * | 10.61 ± 1.59 * |

| AVA-D-S (cm) | 1.54 ± 0.13 | 2.05 ± 0.14 † | 2.53 ± 0.13 †,‡ | 1.58 ± 0.20 | 2.01 ± 0.20 † | 2.45 ± 0.20 †,‡ | 1.58 ± 0.20 | 2.02 ± 0.20 † | 2.46 ± 0.19 † |

| AVA-A-S (cm2) | 2.26 ± 0.50 | 3.29 ± 0.56 † | 4.65 ± 0.69 †,‡ | 1.94 ± 0.26 | 3.20 ± 0.45 † | 4.70 ± 0.50 †,‡ | 1.99 ± 0.32 | 3.23 ± 0.48 † | 4.71 ± 0.52 † |

| AVA-P-S (cm) | 5.31 ± 0.59 | 6.50 ± 0.56 † | 7.66 ± 0.62 †,‡ | 5.00 ± 0.38 | 6.40 ± 0.47 † | 7.54 ± 0.44 †,‡ | 5.02 ± 0.38 | 9.10 ± 0.55 † | 7.79 ± 0.42 † |

| AVA-D-D (cm) | 1.74 ± 0.30 | 2.00 ± 0.96 † | 2.32 ± 0.31 †,‡ | 1.64 ± 0.24 | 1.98 ± 0.28 † | 2.33 ± 0.29 †,‡ | 1.65 ± 0.24 | 6.43 ± 0.47 † | 2.36 ± 0.27 †,‡ |

| AVA-A-D (cm2) | 2.27 ± 0.54 | 3.17 ± 0.77 † | 4.00 ± 0.88 †,‡ | 2.06 ± 0.45 | 3.08 ± 0.72 † | 4.10 ± 0.76 †,‡ | 2.06 ± 0.44 | 3.09 ± 0.71 † | 4.15 ± 0.70 †,‡ |

| AVA-P-D (cm) | 5.43 ± 0.67 | 6.27 ± 0.85 † | 7.11 ± 0.79 †,‡ | 5.16 ± 0.61 | 6.20 ± 0.79 † | 7.22 ± 0.68 †,‡ | 5.16 ± 0.60 | 6.21 ± 0.78 † | 7.27 ± 0.63 †,‡ |

| ES-AVA > ED-AVA (%) | 15 (60) | 47 (53) | 19 (95) †,‡ | 7 (39) | 53 (58) | 21 (88) †,‡ | 8 (42) | 53 (57) | 20 (91) †,‡ |

4. Discussion

- -

- One of the most important technical limitations is the poorer image quality observed during 3DSTE as compared to that of 2D echocardiography, which still exists today. This may be due to the larger probe, stitching artifacts that may occur during the merging of digitally acquired 3D echocardiographic subvolumes, or the presence of arrhythmias, among other factors. Impact of sample rates and potential phase shifts on accurately capturing true maximum and minimum phases could significantly affect findings, which could be considered as the most important limitation of the present study [7,8,9,10,11].

- -

- -

- Moreover, chamber quantification of any atria and ventricles was not aimed to be performed either, due to the fact that the present study focused solely on the simultaneous measurement of valvular annuli.

- -

- -

- Valvular regurgitations were excluded only by visual assessment, and more advanced methods were not applied during assessments.

- -

- Due to the use of certain statistical methods, the results obtained can only be interpreted in light of them. First, given the large number of comparisons, the risk of a type I error (false positives) in this study was very high. Second, forced stratification of continuous variables results in substantial information loss and reduces statistical power.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ormiston, J.A.; Shah, P.M.; Tei, C.; Wong, M. Size and motion of the mitral valve annulus in man. I. A two-dimensional echocardiographic method and findings in normal subjects. Circulation 1981, 64, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbiger, J.J. Anatomy, mechanics, and pathophysiology of the mitral annulus. Am. Heart J. 2012, 164, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaila, S.; Muraru, D.; Miglioranza, M.H.; Piasentini, E.; Peluso, D.; Cucchini, U.; Iliceto, S.; Vinereanu, D.; Badano, L.U. Normal mitral annulus dynamics and its relationships with left ventricular and left atrial function. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015, 31, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbiger, J.J.; Bazaz, R. The anatomic substrate of mitral annular contraction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 306, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukas, M.; Bilinsky, E.; Bilinsky, S.; Blaak, C.; Tubbs, R.S.; Anderson, R.H. The anatomy of the aortic root. Clin. Anat. 2014, 27, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.H. Clinical anatomy of the aortic root. Heart 2000, 84, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemes, A.; Kormányos, Á.; Lengyel, C. Comparison of dimensions and functional features of mitral and tricuspid annuli in the same healthy adults: Insights from the three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiographic MAGYAR-Healthy Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2024, 14, 6780–6791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franke, A.; Kuhl, H.P. Second-generation real-time 3D echocardiography: A revolutionary new technology. MedicaMundi 2003, 47, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, K.A.; Paterick, T.E.; Khandheria, B.K.; Jan, M.F.; Kramer, C.; Umland, M.M.; Tercius, A.J.; Baratta, L.; Tajik, A.J. Myocardial mechanics: Understanding and applying three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in clinical practice. Echocardiography 2012, 29, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbano-Moral, J.A.; Patel, A.R.; Maron, M.S.; Arias-Godinez, J.A.; Pandian, N.G. Three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography: Methodological aspects and clinical potential. Echocardiography 2012, 29, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraru, D.; Niero, A.; Rodriguez-Zanella, H.; Cherata, D.; Badano, L. Three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography: Benefits and limitations of integrating myocardial mechanics with three-dimensional imaging. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 8, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemes, A.; Kormányos, Á.; Domsik, P.; Kalapos, A.; Gyenes, N.; Lengyel, C. Normal reference values of three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography-derived mitral annular dimensions and functional properties in healthy adults: Insights from the MAGYAR-Healthy Study. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2021, 49, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemes, A.; Ambrus, N.; Lengyel, C. Normal reference values of three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography-derived aortic valve annular dimensions in healthy adults-a detailed analysis from the MAGYAR-Healthy Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2025, 15, 6776–6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 16, 233–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigenbaum, H. (Ed.) Echocardiography, 5th ed.; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.C.; Mariani, J., Jr.; Falcão, B.A.A.; Filho, A.E.; Nomura, C.H.; Avila, L.F.R.; Parga, J.R.; Lemos Neto, P.A. Differences between systolic and diastolic dimensions of the aortic valve annulus in computed tomography angiography in patients undergoing percutaneous implantation of aortic valve prosthesis by catheter. Rev. Bras. Cardiol. Invasiva 2015, 23, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tamborini, G.; Fusini, L.; Muratori, M.; Cefalù, C.; Gripari, P.; Ali, S.G.; Pontone, G.; Andreini, D.; Bartorelli, A.L.; Alamanni, F.; et al. Feasibility and accuracy of three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography vs. multidetector computed tomography in the evaluation of aortic valve annulus in patient candidates to transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 15, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, A.M.; Soliman, O.I.; ten Cate, F.J.; Nemes, A.; McGhie, J.S.; Krenning, B.J.; van Geuns, R.J.; Galema, T.W.; Geleijnse, M.L. True mitral annulus diameter is underestimated by two-dimensional echocardiography as evidenced by real-time three-dimensional echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2007, 23, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemes, A.; Ambrus, N.; Lengyel, C. Does left ventricular rotational mechanics depend on aortic valve annular dimensions in healthy adults?—A three-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography-derived analysis from the MAGYAR-Healthy Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data | Measures |

|---|---|

| Clinical data | |

| n | 134 |

| Mean age (years) | 31.0 (16.0) |

| Males (%) | 73 (54) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 116 ± 7 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 ± 8 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72 ± 2 |

| Weight (kg) | 72.0 (19.0) |

| Height (cm) | 172.0 (14.3) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 (4.3) |

| Two-dimensional echocardiographic data | |

| LA diameter (mm) | 37.3 ± 3.6 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm) | 48.4 ± 3.7 |

| LV end-systolic diameter (mm) | 32.1 ± 3.1 |

| LV end-diastolic volume (mL) | 107.4 ± 23.7 |

| LV end-systolic volume (mL) | 37.9 ± 9.0 |

| Interventricular septum (mm) | 9.2 ± 1.2 |

| LV posterior wall (mm) | 9.4 ± 1.5 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 65.0 ± 3.9 |

| Early diastolic mitral inflow velocity—E (cm/s) | 79.4 (22.0) |

| Late diastolic mitral inflow velocity—A (cm/s) | 56.7 (15.2) |

| MVA-D-S | MVA-A-S | MVA-P-S | MVA-D-D | MVA-A-D | MVA-P-D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA-D-S | 1 | 0.787 (p < 0.001) | 0.652 (p < 0.001) | 0.328 (p < 0.001) | 0322 (p < 0.001) | 0.274 (p = 0.001) |

| MVA-A-S | 0.787 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.956 (p < 0.001) | 0.449 (p < 0.001) | 0.511 (p < 0.001) | 0.480 (p < 0.001) |

| MVA-P-S | 0.652 (p < 0.001) | 0.956 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.442 (p < 0.001) | 0.528 (p < 0.001) | 0511 (p < 0.001) |

| MVA-D-D | 0.328 (p < 0.001) | 0.449 (p < 0.001) | 0.442 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.805 (p < 0.001) | 0.701 (p < 0.001) |

| MVA-A-D | 0.322 (p < 0.001) | 0.511 (p < 0.001) | 0.528 (p < 0.001) | 0.805 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.967 (p < 0.001) |

| MVA-P-D | 0.274 (p = 0.001) | 0.480 (p < 0.001) | 0.511 (p < 0.001) | 0.701 (p < 0.001) | 0.967 (p < 0.001) | 1 |

| AVA-D-S | −0.069 (p = 0.429) | 0.087 (p = 0.317) | 0.115 (p = 0.184) | 0.089 (p = 0.308) | 0.057 (p = 0.510) | 0.041 (p = 0.642) |

| AVA-A-S | −0.052 (p = 0.552) | 0.081 (p = 0.351) | 0.102 (p = 0.241) | 0.112 (p = 0.198) | 0.096 (p = 0.269) | 0.087 (p = 0.316) |

| AVA-P-S | −0.056 (p = 0.518) | 0.104 (p = 0.231) | 0.125 (p = 0.149) | 0.106 (p = 0.223) | 0.115 (p = 0.184) | 0.112 (p = 0.197) |

| AVA-D-D | −0.057 (p = 0.515) | 0.124 (p = 0.154) | 0.137 (p = 0.114) | 0.180 (p = 0.036) | 0.188 (p = 0.030) | 0.186 (p = 0.032) |

| AVA-A-D | −0.062 (p = 0.479) | 0.140 (p = 0.107) | 0.166 (p = 0.055) | 0.153 (p = 0.078) | 0.136 (p = 0.118) | 0.136 (p = 0.118) |

| AVA-P-D | −0.038 (p = 0.662) | 0.168 (p = 0.052) | 0.194 (p = 0.025) | 0.202 (p = 0.019) | 0.184 (p = 0.033) | 0.187 (p = 0.030) |

| AVA-D-S | AVA-A-S | AVA-P-S | AVA-D-D | AVA-A-D | AVA-P-D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MVA-D-S | −0.069 (p = 0.429) | −0.052 (p = 0.552) | −0.056 (p = 0.518) | −0.057 (p = 0.514) | −0.062 (p = 0.479) | −0.038 (p = 0.662) |

| MVA-A-S | 0.087 (p = 0.317) | 0.081 (p = 0.351) | 0.104 (p = 0.231) | 0.124 (p = 0.154) | 0.140 (p = 0.107) | 0.168 (p = 0.052) |

| MVA-P-S | 0.115 (p = 0.184) | 0.102 (p = 0.241) | 0.125 (p = 0.149) | 0.137 (p = 0.114) | 0.166 (p = 0.055) | 0.194 (p = 0.025) |

| MVA-D-D | 0.089 (p = 0.308) | 0.112 (p = 0.198) | 0.106 (p = 0.223) | 0.180 (p = 0.038) | 0.153 (p = 0.078) | 0.202 (p = 0.019) |

| MVA-A-D | 0.057 (p = 0.510) | 0.096 (p = 0.269) | 0.115 (p = 0.184) | 0.188 (p = 0.030) | 0.136 (p = 0.118) | 0.184 (p = 0.033) |

| MVA-P-D | 0.041 (p = 0.642) | 0.087 (p = 0.316) | 0.112 (p = 0.197) | 0.186 (p = 0.032) | 0.136 (p = 0.118) | 0.187 (p = 0.030) |

| AVA-D-S | 1 | 0.866 (p < 0.001) | 0.878 (p < 0.001) | 0.636 (p < 0.001) | 0.685 (p < 0.001) | 0.603 (p < 0.001) |

| AVA-A-S | 0.866 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.986 (p < 0.001) | 0.696 (p < 0.001) | 0.777 (p < 0.001) | 0.738 (p < 0.001) |

| AVA-P-S | 0.878 (p < 0.001) | 0.986 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.704 (p < 0.001) | 0.792 (p < 0.001) | 0.741 (p < 0.001) |

| AVA-D-D | 0.636 (p < 0.001) | 0.696 (p < 0.001) | 0.704 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.836 (p < 0.001) | 0.811 (p < 0.001) |

| AVA-A-D | 0.685 (p < 0.001) | 0.777 (p < 0.001) | 0.792 (p < 0.001) | 0.836 (p < 0.001) | 1 | 0.785 (p < 0.001) |

| AVA-P-D | 0.603 (p < 0.001) | 0.738 (p < 0.001) | 0.741 (p < 0.001) | 0.811 (p < 0.001) | 0.785 (p < 0.001) | 1 |

| Intraobserver Agreement | Interobserver Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± 2SD Difference in Values Obtained by 2 Measurements of the Same Observer | ICC Between Measurements of the Same Observer | Mean ± 2SD Difference in Values Obtained by 2 Observers | ICC Between Independent Measurements of 2 Observers | |

| MVA-D-S (cm) | −0.03 ± 0.12 cm | 0.95 (p < 0.0001) | 0.04 ± 0.15 cm | 0.97 (p < 0.0001) |

| MVA-A-S (cm2) | −0.03 ± 0.20 cm2 | 0.97 (p < 0.0001) | −0.04 ± 0.59 cm2 | 0.96 (p < 0.0001) |

| MVA-P-S (cm) | 0.05 ± 0.79 cm | 0.97 (p < 0.0001) | 0.05 ± 0.51 cm | 0.96 (p < 0.0001) |

| MVA-D-D (cm) | 0.02 ± 0.16 cm | 0.96 (p < 0.0001) | 0.03 ± 0.18 cm | 0.98 (p < 0.0001) |

| MVA-A-D (cm2) | −0.03 ± 0.83 cm2 | 0.96 (p < 0.0001) | 0.04 ± 0.58 cm2 | 0.96 (p < 0.0001) |

| MVA-P-D (cm) | −0.03 ± 0.80 cm | 0.97 (p < 0.0001) | −0.08 ± 0.68 cm | 0.96 (p < 0.0001) |

| AVA-D-S (cm) | 0.03 ± 0.30 | 0.91 (p < 0.0001) | 0.04 ± 0.28 | 0.94 (p < 0.0001) |

| AVA-A-S (cm2) | 0.09 ± 0.72 | 0.91 (p < 0.0001) | 0.10 ± 0.74 | 0.93 (p < 0.0001) |

| AVA-P-S (cm) | −0.03 ± 0.58 | 0.91 (p < 0.0001) | 0.02 ± 0.49 | 0.93 (p < 0.0001) |

| AVA-D-D (cm) | −0.03 ± 0.23 | 0.89 (p < 0.0001) | −0.06 ± 0.18 | 0.90 (p < 0.0001) |

| AVA-A-D (cm2) | −0.10 ± 0.58 | 0.93 (p < 0.0001) | −0.11 ± 0.50 | 0.93 (p < 0.0001) |

| AVA-P-D (cm) | −0.07 ± 0.59 | 0.92 (p < 0.0001) | −0.11 ± 0.62 | 0.94 (p < 0.0001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nemes, A.; Bordács, B.; Ambrus, N.; Lengyel, C. The Complexity of the Relationship Between Mitral and Aortic Valve Annular Dimensions in the Same Healthy Adults: Detailed Insights from the Three-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiographic MAGYAR-Healthy Study. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020304

Nemes A, Bordács B, Ambrus N, Lengyel C. The Complexity of the Relationship Between Mitral and Aortic Valve Annular Dimensions in the Same Healthy Adults: Detailed Insights from the Three-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiographic MAGYAR-Healthy Study. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(2):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020304

Chicago/Turabian StyleNemes, Attila, Barbara Bordács, Nóra Ambrus, and Csaba Lengyel. 2026. "The Complexity of the Relationship Between Mitral and Aortic Valve Annular Dimensions in the Same Healthy Adults: Detailed Insights from the Three-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiographic MAGYAR-Healthy Study" Biomedicines 14, no. 2: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020304

APA StyleNemes, A., Bordács, B., Ambrus, N., & Lengyel, C. (2026). The Complexity of the Relationship Between Mitral and Aortic Valve Annular Dimensions in the Same Healthy Adults: Detailed Insights from the Three-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiographic MAGYAR-Healthy Study. Biomedicines, 14(2), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020304