Nasal Cytology Is Useful for Evaluating and Monitoring the Therapeutic Response to Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Clinical Assessment

- Score 0: no polyps;

- Score 1: small polyps in the middle meatus not extending below the inferior border of the middle turbinate;

- Score 2: polyps reaching below the lower border of the middle turbinate;

- Score 3: large polyps reaching the lower border of the inferior turbinate or polyps medial to the middle turbinate;

- Score 4: large polyps causing near-complete congestion or nasal obstruction of the inferior meatus.

2.5. Criteria for Selecting Biologics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

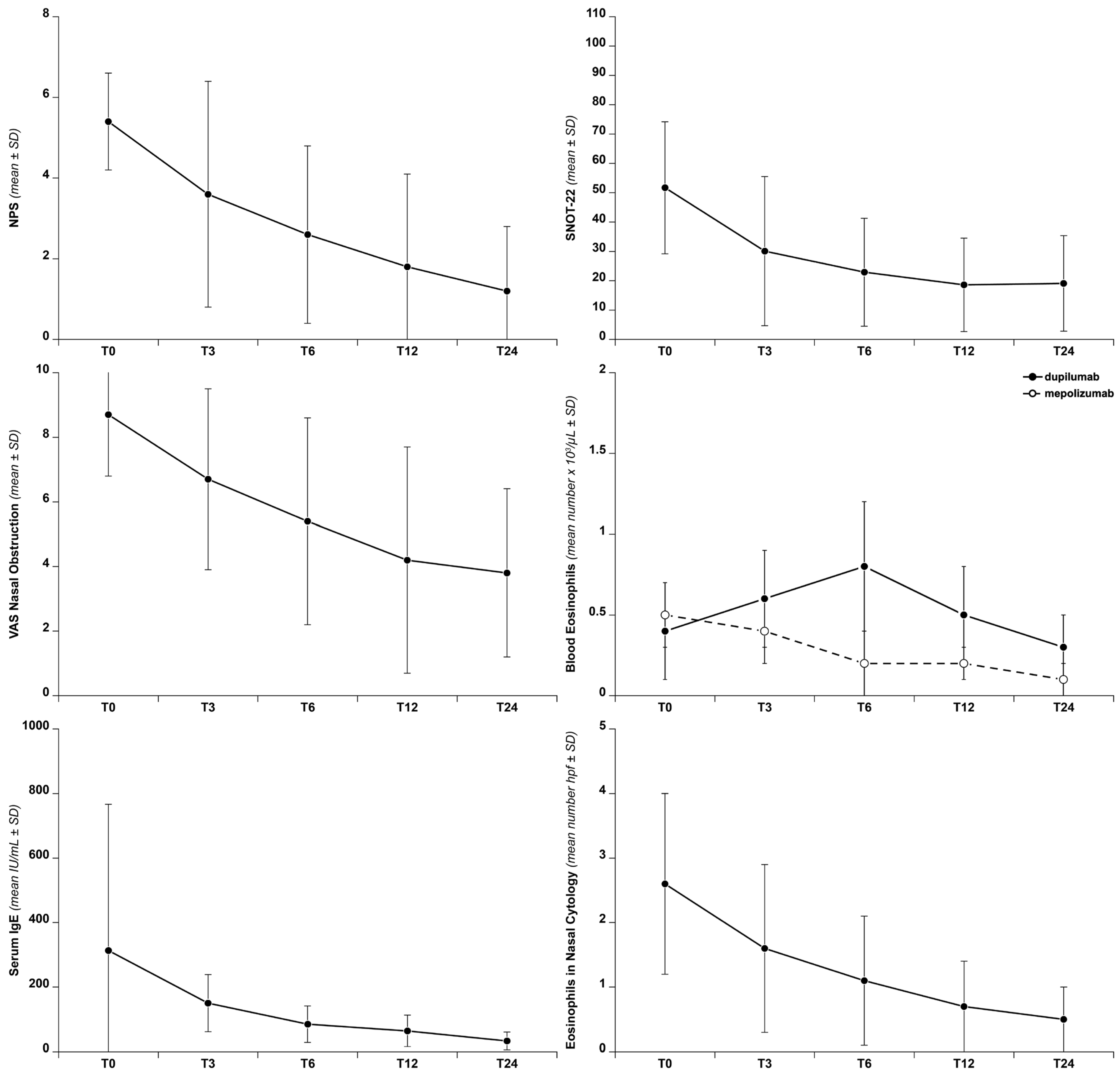

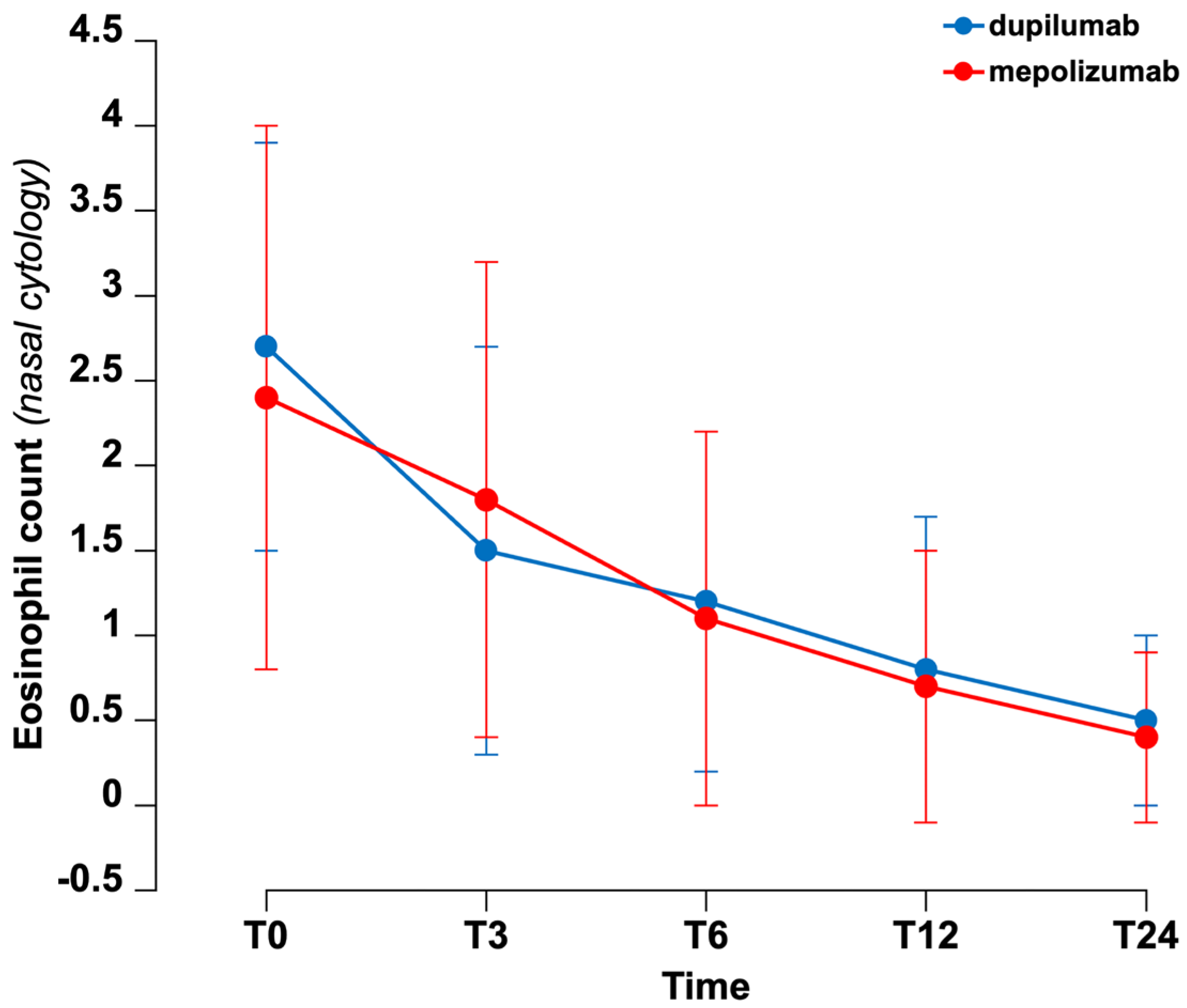

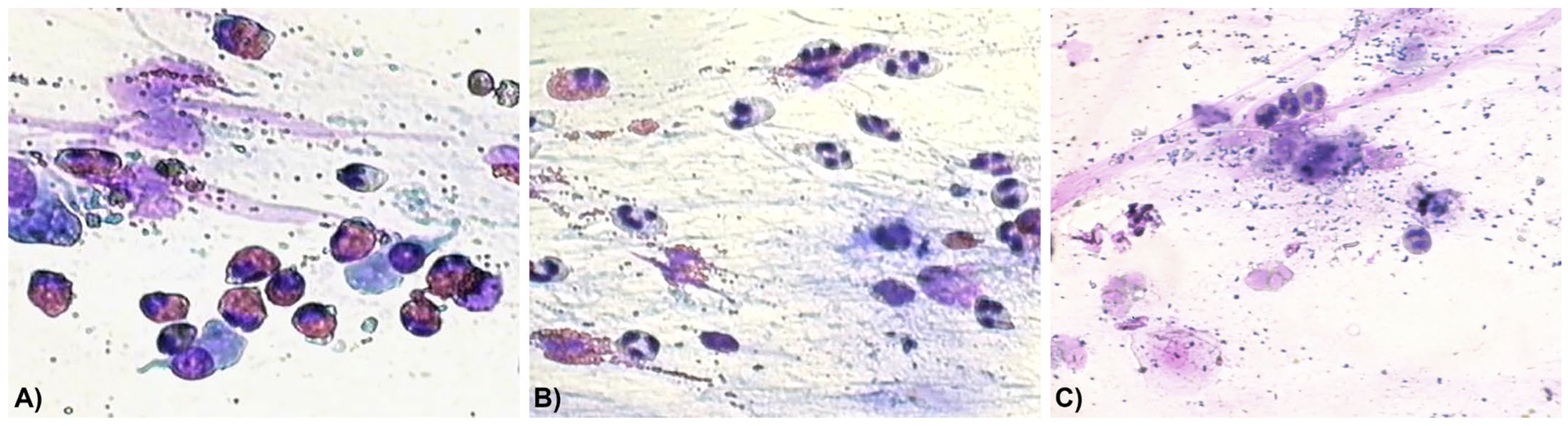

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRSwNP | Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis |

| OCS | Oral corticosteroids |

| INCS | Intranasal corticosteroids |

| NPS | Nasal Polyp Score |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| SNOT-22 | Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 |

| ACT | Asthma Control Test |

| CCG | Clinical Cytological Grading |

References

- De Corso, E.; Bellocchi, G.; De Benedetto, M.; Lombardo, N.; Macchi, A.; Malvezzi, L.; Motta, G.; Pagella, F.; Vicini, C.; Passali, D. Biologics for severe uncontrolled chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: A change management approach. Consensus of the Joint Committee of Italian Society of Otorhinolaryngology on biologics in rhinology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2022, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardell, L.O.; Stjarne, P.; Jonstam, K.; Bachert, C. Endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: Impact on management. J. All. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, L.Y.; Piromchai, P.; Sharp, S.; Snidvongs, K.; E Webster, K.; Philpott, C.; Hopkins, C.; Burton, M.J. Biologics for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 3, CD013513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre, M.; Bacci, E.; Seccia, V.; Bartoli, M.L.; Cardini, C.; Cianchetti, S.; Cristofani, L.; Di Franco, A.; Miccoli, M.; Puxeddu, I.; et al. Upper and lower airway inflammation in severe asthmatics: A guide for a precision biologic treatment. Ther. Adv. Resp. Dis. 2020, 14, 1753466620965151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleimer, R.P.; Berdnikovs, S. Etiology of epithelial barrier dysfunction in patients with type 2 inflammatory diseases. J. All. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIFA Treatment Plan for the Prescription of Dupixent (Dupilumab), Xolair (Omalizumab) and Nucala (Mepolizumab) in the Treatment of Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps (CRSwNP) (2024). Available online: www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2024/11/08/262/sg/pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Stoop, A.E.; Van Der Heijden, H.A.; Biewenga, J.; Van Der Baan, S. Eosinophils in nasal polyps and nasal mucosa: An immunohistochemical study. J. All. Clin. Immunol. 1993, 91, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, S.; Bandi, F.; Preti, A.; Facco, C.; Ottini, G.; Di Candia, F.; Mozzanica, F.; Saderi, L.; Sessa, F.; Reguzzoni, M.; et al. Exploring the role of nasal cytology in chronic rhinosinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, G.; Malvezzi, L.; Riccio, A.M.; Descalzi, D.; Pirola, F.; Russo, E.; De Ferrari, L.; Racca, F.; Ferri, S.; Messina, M.R.; et al. Nasal cytology as a reliable non-invasive procedure to phenotype patients with type 2 chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Worl All. Org. J. 2022, 15, 100700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelardi, M.; Iannuzzi, L.; Quaranta, N.; Landi, M.; Passalacqua, G. Nasal cytology: Pratical aspects and clinical relevance. Clin. Exp. All 2016, 46, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhar, H.N.; Tajudeen, B.A.; Mahdavinia, M.; Gattuso, P.; Ghai, R.; Batra, P.S. Inflammatory infiltrate and mucosal remodeling in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without polyps: Structured histopathologic analysis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, T.; Snidvongs, K.; Xie, M.; Banglawala, S.; Sommer, D. High tissue eosinophilia as a marker to predict recurrence for eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torretta, S.; Piatti, G.; Catalano, C.; Ferrucci, S.; Cavallini, M.; Rivolta, F.; Bellocchi, C.; D’aDda, A.; Battilocchi, L.; Tavecchio, S.; et al. Effectiveness of dupilumab treatment in patients with type 2 inflammation: A real-life integrated experience. Ther. Adv. All. Rhinol. 2025, 16, 27534030241312540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Viskens, A.S.; Backer, V.; Conti, D.; De Corso, E.; Gevaert, P.; Scadding, G.K.; Wagemann, M.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Chaker, A.; et al. EPOS/EUFOREA update on indication and evaluation of biologics in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps 2023. Rhinology 2023, 61, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitsma, S.; Adriaensen, G.F.J.P.M.; Cornet, M.E.; Van Haastert, R.M.; Raftopulos, M.; Fokkens, W. The Amsterdam Classification of Completeness of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (ACCESS): A new CT-based scoring system grading the extent of surgery. Rhinology 2020, 58, 538–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, V.J.; MacKay, I.S. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 1993, 31, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, C.; Gillett, S.; Slack, R.; Lund, V.J.; Browne, J.P. Psychometric validity of the 22-item Sinonasal Outcome Test. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2009, 34, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corso, E.; Corbò, M.; Montuori, C.; Fumo, D.; Seccia, V.; Di Cesare, T.; Pipolo, C.; Baroni, S.; Mastrapasqua, R.; Rizzuti, A.; et al. Blood and local nasal eosinophilia in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: Prevalence and correlation with severity of disease. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2025, 45, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelardi, M.; Piccininni, K.; Quaranta, N.; Quaranta, V.; Quaranta, V.; Silvestri, M.; Ciprandi, G. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is associated with clinical-cytological grading severity. Acta Otolaryngol. Ital. 2019, 39, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelardi, M.; Iannuzzi, L.; De Giosa, M.; Taliente, S.; De Candia, N.; Quaranta, N.; De Corso, E.; Seccia, V.; Ciprandi, G. Non-surgical management of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps based on clinical cytological grading: A precision medicine-based approach. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2017, 37, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, R.A.; Sorkness, C.A.; Kosinski, M.; Schatz, M.; Li, J.T.; Marcus, P.; Murray, J.J.; Pendergraft, T.B. Development of the Asthma Control Test: A survey for assessing asthma control. J. All. Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviano, G.; Saccardo, T.; Roccuzzo, G.; Bernardi, R.; Di Chicco, A.; Pendolino, A.L.; Scarpa, B.; Mairani, E.; Nicolai, P. Effectiveness of dupilumab in the treatment of patients with uncontrolled severe CRSwNP: A “real-life” observational study in naïve and post-surgical patients. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofalo, A.; Loperfido, A.; Baroncelli, S.; Masieri, S.; Bellocchi, G.; Caramia, R.; Cascone, F.; Filaferro, L.; Re, F.L.; Cavaliere, C. Comparison between clinical and cytological findings in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps treated with dupilumab. Eur. Arch. Oto Rhino Laryngol. 2024, 281, 6511–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danishman, Z.; Linxweiler, M.; Kuhn, J.P.; Linxweiler, B.; Solomayer, E.-F.; Wagner, M.; Wagenpfeil, G.; Schick, B.; Differential, S.B. nasal swab cytology represents a valuable tool for therapy monitoring but not prediction of therapy response in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps treated with dupilumab. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1127576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelardi, M.; Giancaspro, R.; Quaranta, V.N.; La Gatta, E.; Ruzza, A.; Cassano, M. Dupilumab’s impact on nasal cytology: Real life experience after 1 year of treatment. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detoraki, A.; Tremante, E.; D’Amato, M.; Calabrese, C.; Casella, C.; Maniscalco, M.; Poto, R.; Brancaccio, R.; Boccia, M.; Martino, M.; et al. Mepolizumab improves sino-nasal symptoms and asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps: A 12-month real-life study. Ther. Adv. Resp. Dis. 2021, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomasi, C.; Buonamico, E.; Dragonieri, S.; Iannuzzi, L.; Portacci, A.; Quaranta, N.; Carpagnano, G.E. Effects of benralizumab in a population of patients affected by severe eosinophilic asthma and chronic rhinosisnusitis with nasal polyps: A real-life study. Acta Biomed. 2023, 94, e20230028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, Y.E.; Kim, J.K.; Lim, H.-S.; Eun, K.M.; Yang, S.K.; Kim, D.W. Elastase-positive neutrophils are associated with refractoriness of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in an Asian population. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2020, 12, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.; Zhang, L. Understanding the role of neutrophils in refractoriness of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2020, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorari, G.; Piazza, F.; Borgione, M.; Prizio, C.; della Mantica, G.G.; Garetto, M.; Gedda, F.; Riva, G. The role of intranasal corticosteroids in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis treated with dupilumab. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2023, 44, 103927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondari, F.; Calvino-Sanles, E.; First, N.J.; Gestal, M.C. Eosinophils and bacteria, the beginning of a story. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaminck, S.; Acke, F.; Scadding, G.K.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Gevaert, P. Pathophysiology and clinical aspects of chronic rhinosinusitis: Current concepts. Front. Allergy 2021, 27, 741788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (45) | Dupilumab (23) | Mepolizumab (22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 21 (46.6) | 13 (56.5) | 8 (36.4) |

| Age (years) | 58.6 ± 13.2 | 58.9 ± 13.6 | 58.3 ± 13.1 |

| Family history of allergies | 19 (42.2) | 6 (26.1) | 13 (59.1) |

| NSAID intolerance | 17 (37.8) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (36.4) |

| Asthma | 32 (71.1) | 17 (73.9) | 15 (68.2) |

| ACT (0–25) | 20.4 ± 4.9 | 20.4 ± 4.8 | 20.3 ± 5.1 |

| Previous sinonasal surgeries | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

| Bilateral NPS (0–8) | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 5.7 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.3 |

| Lund-McKay score (0–24) | 12.6 ± 5.8 | 13.4 ± 6.2 | 11.8 ± 5.6 |

| Clinical Cytological Grading | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 1 | 4.5 ± 1.3 |

| SNOT-22 (0–110) | 51.7 ± 22.5 | 57.3 ± 17 | 46.1 ± 6.2 |

| VAS nasal obstruction (0–10) | 8.7 ± 1.9 | 9 ± 1.9 | 8.3 ± 2.3 |

| VAS smell (0–10) | 7.6 ± 2.5 | 7.8 ± 2.2 | 7.4 ± 2.8 |

| Blood eosinophils (×103/µL) | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| IgE level (IU/mL) | 313.2 ± 453.5 | 201.4 ± 370.4 | 425.2 ± 519.7 |

| Variables | r | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Blood eosinophils vs. nasal eosinophils | 0.03 | 0.89 |

| Blood eosinophils vs. SNOT-22 | −0.28 | 0.18 |

| Blood eosinophils vs. NPS | −0.19 | 0.32 |

| Nasal eosinophils vs. SNOT-22 | −0.03 | 0.89 |

| Nasal eosinophils vs. NPS | 0.18 | 0.31 |

| Nasal eosinophils vs. VAS nasal obstruction | −0.12 | 0.53 |

| Nasal eosinophils vs. CCG | 0.35 * | 0.02 |

| NPS vs. SNOT-22 | 0.21 | 0.32 |

| NPS vs. VAS nasal obstruction | 0.38 * | 0.05 |

| NPS vs. CCG | 0.05 | 0.76 |

| SNOT-22 vs. VAS nasal obstruction | 0.18 | 0.43 |

| SNOT-22 vs. CCG | 0.05 | 0.80 |

| SNOT-22 vs. ACT | −0.52 * | 0.01 |

| T0 | T3 | T6 | T12 | T24 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eosinophils | 11 (24.4) | 8 (17.7) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| Eosinophils + mast cells | 7 (15.6) | 5 (11.1) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Neutrophils | 9 (20) | 15 (33.3) | 16 (35.6) | 20 (44.4) | 22 (48.9) |

| Neutrophils + eosinophils | 18 (40) | 14 (31.1) | 11 (24.4) | 6 (13.3) | 0 (0) |

| Neutrophils + bacteria | 0 (0) | 2 (4.4) | 6 (13.3) | 9 (20) | 11 (24.4) |

| Negative nasal cytology | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (11.1) | 9 (20) | 12 (26.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Piatti, G.; Battilocchi, L.; Cozzi, A.; Gaini, L.M.; Aldè, M.; Pignataro, L.; Torretta, S. Nasal Cytology Is Useful for Evaluating and Monitoring the Therapeutic Response to Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010077

Piatti G, Battilocchi L, Cozzi A, Gaini LM, Aldè M, Pignataro L, Torretta S. Nasal Cytology Is Useful for Evaluating and Monitoring the Therapeutic Response to Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010077

Chicago/Turabian StylePiatti, Gioia, Ludovica Battilocchi, Anna Cozzi, Lorenzo Maria Gaini, Mirko Aldè, Lorenzo Pignataro, and Sara Torretta. 2026. "Nasal Cytology Is Useful for Evaluating and Monitoring the Therapeutic Response to Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010077

APA StylePiatti, G., Battilocchi, L., Cozzi, A., Gaini, L. M., Aldè, M., Pignataro, L., & Torretta, S. (2026). Nasal Cytology Is Useful for Evaluating and Monitoring the Therapeutic Response to Biologics in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis. Biomedicines, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010077