Microbiota-Driven Immune Dysregulation Along the Gut–Lung–Vascular Axis in Asthma and Atherosclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

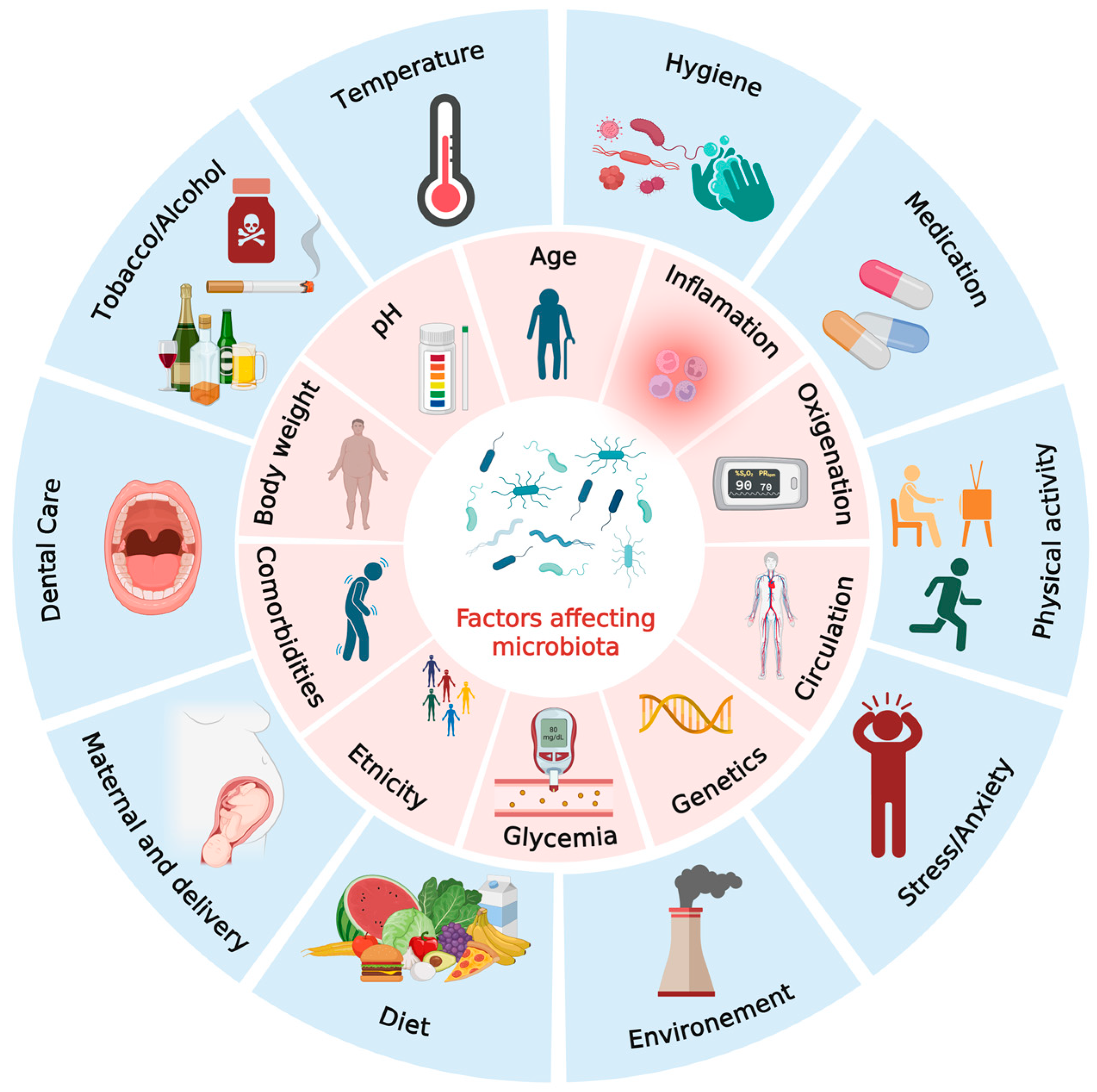

2. Microbiota: An Overview

2.1. Diet

2.2. Medication Use

2.3. Age

2.4. Host Genetics and Physiology

2.5. Maternal Microbiota and Early-Life Microbial Exposures

2.6. Environmental Exposures

2.7. Chronic Conditions

2.8. Lifestyle Factors

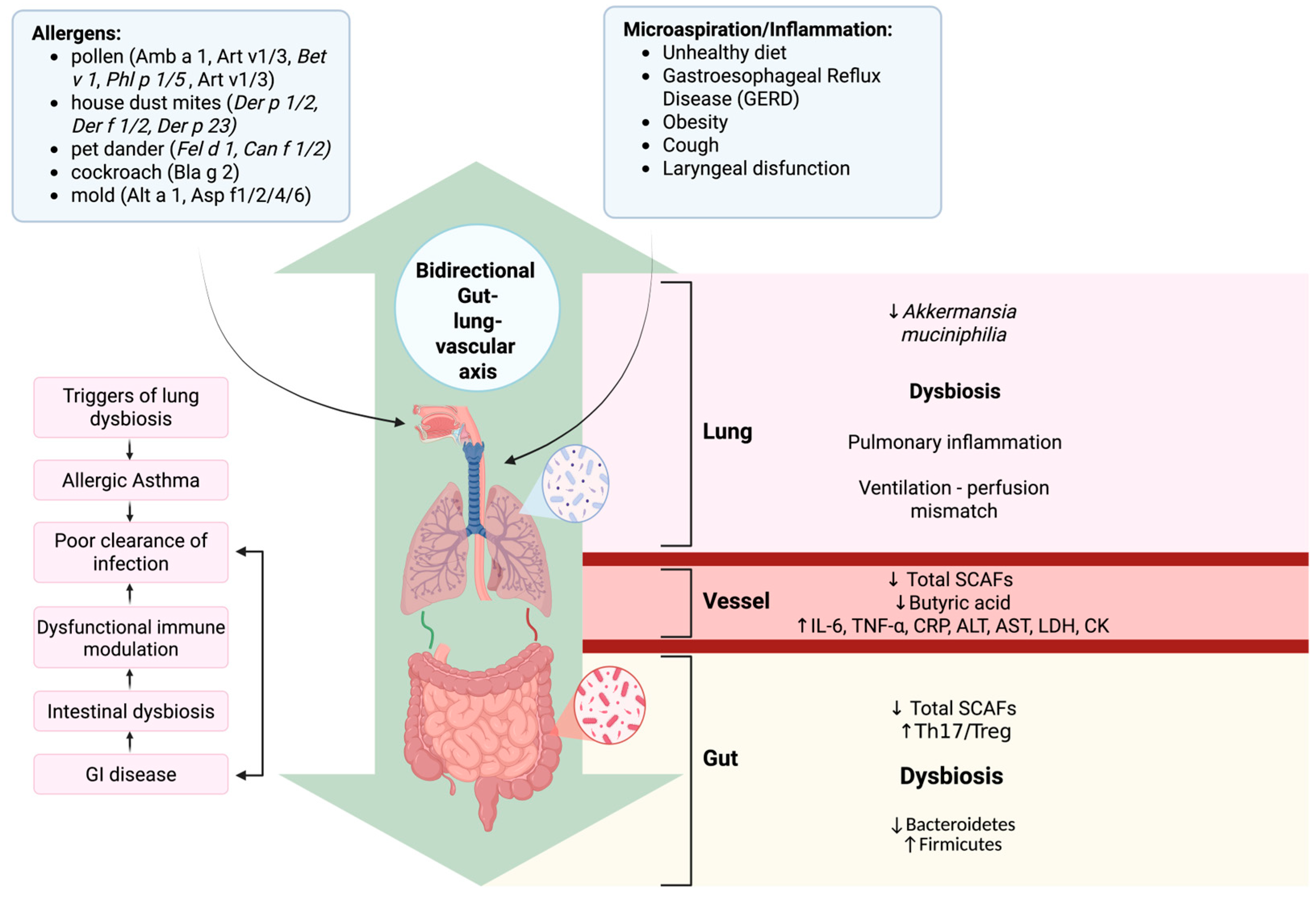

3. Microbiota in Allergic Asthma

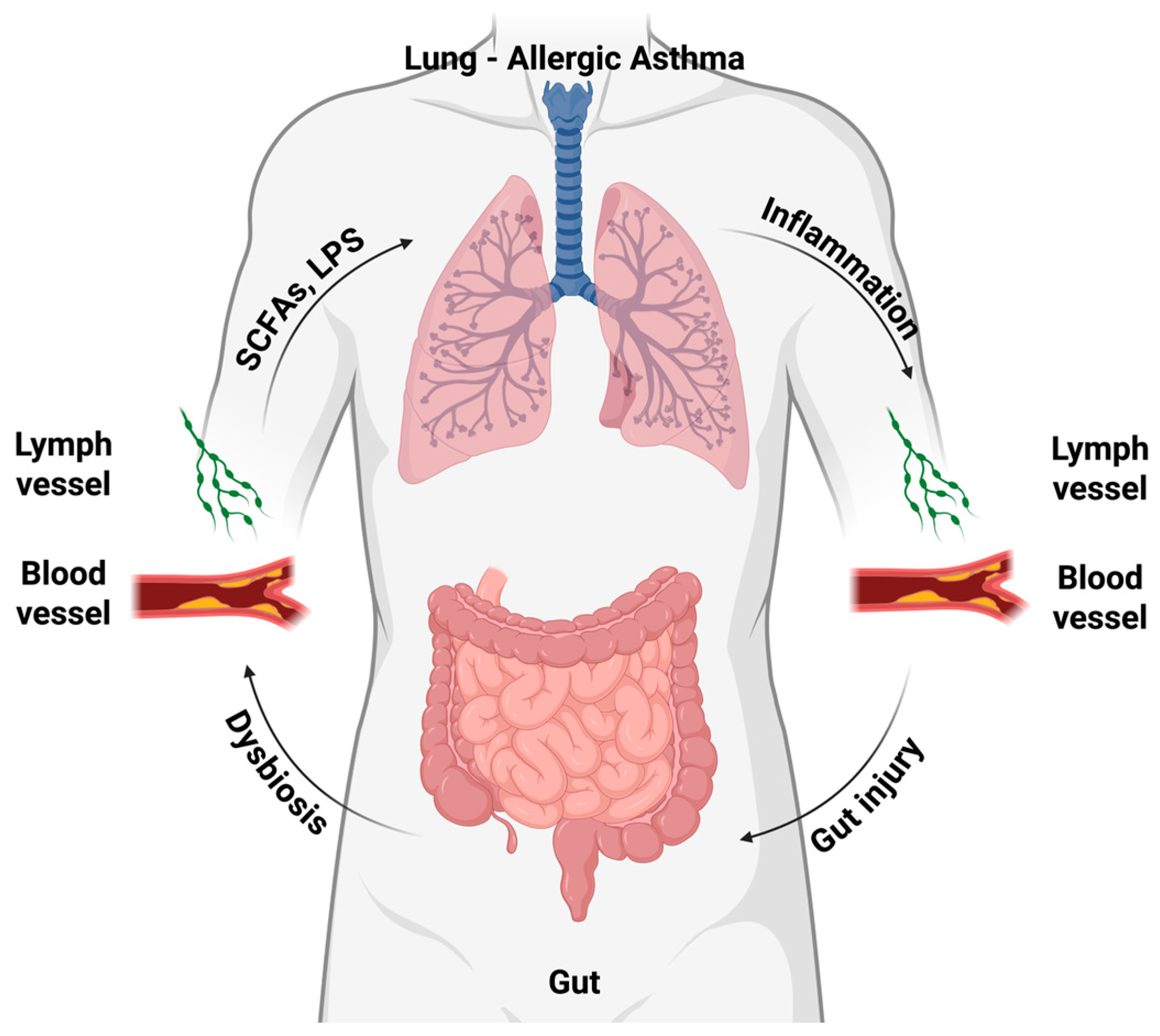

3.1. Evidence for the Gut–Lung Axis in Asthma

3.2. Microbial Taxa Associated with Allergic Asthma

- Airway Microbiome

- Gut Microbiome

3.3. Mechanisms: Immune Modulation and Metabolite Signaling

- SCFAs such as acetate, propionate and butyrate are fermentation products of dietary fibers by Clostridia species. SCFAs enhance Treg expansion, suppress airway eosinophilia and modulate gene expression through histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibition and G-protein-coupled receptor (GPR41, GPR43, GPR109A) activation [146]. Early-life exposure to propionate, including through breast milk, has been associated with reduced airway inflammation, while short-chain fatty acids modulate immune responses through HDAC and activation of G-protein-coupled receptors [147,148,149]. Recent studies also show that butyrate can selectively inhibit Tfh13 cells involved in allergic sensitization [136,148,149].

- Tryptophan metabolites, particularly indole derivatives, act as ligands for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), promoting epithelial integrity and limiting allergic inflammation [31]. Recent studies in asthma show that type-2 inflammation perturbs tryptophan metabolism and that exogenous indoles restore microbial diversity, reduce OVA-IgE/cytokines and ameliorate airway disease in vivo through AhR-dependent signaling [150].

- Secondary bile acids generated by gut microbial metabolism may also exert systemic immunoregulatory effects, though their contribution to asthma pathophysiology remains less well characterized [138]. Secondary BA supplementation has been shown to reduce allergen-driven airway inflammation, but evidence in human asthma remains limited and inconsistent [28].

3.4. Microbiota-Targeted Interventions: Probiotics, Prebiotics and Dietary Modulation

- Probiotics: Supplementation with Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Lachnospira or Akkermansia strains has shown potential to reduce airway inflammation and improve asthma control, though clinical results remain heterogeneous and strain-specific [151]. The PRObiotics in Pediatric Asthma Management (PROPAM) study evaluated the efficacy of a probiotic formulations containing Ligilactobacillus salivarius LS01 + Bifidobacterium breve B632. A reduction in both the incidence and severity of asthma exacerbations was observed among the children receiving probiotic supplementation [152]. Multistrain formulations containing Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species have been shown to enhance asthma symptom control and modulate inflammatory biomarkers, although their impact on lung function parameters remains variable across studies [151]. Recent review on gut–lung axis modulation identifies Lachnospira as a short-chain fatty acid-producing genus associated with protective, anti-inflammatory effects in asthma, though direct clinical evidence from supplementation trials remains limited [19].

- Prebiotics and dietary modulation: High-fiber diets enhance SCFA production, improve mucosal immune tolerance and reduce airway hyperresponsiveness in animal models [19]. In murine allergic asthma models, a high-fiber diet (or cellulose-enriched diet) attenuated airway inflammation and symptoms, altered gut microbial composition toward beneficial taxa and in some cases increased SCFAs [153]. Human observational data associate higher fiber intake with reduced biomarkers of airway inflammation and better asthma control, though prospective evidence is limited [154]. Increasing the intake of fermentable foods are being explored as adjuncts in asthma therapy with the aim of modulating the gut–lung axis via microbiota and metabolite pathways [19,155]. Higher fiber intake during mid-childhood appears to be associated with a lower risk of allergen sensitization later in life, although part of this association may reflect reduced exposure to dietary allergens due to food avoidance in sensitized individuals [154]. Dietary interventions targeting microbiota composition are being actively explored as adjunctive strategies for asthma management.

- Advanced approaches: Innovative microbiome-based approaches, including fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and helminth-derived immunomodulators, have recently attracted interest as potential adjunctive strategies for restoring immune balance in allergic asthma. Experimental studies indicate that transferring gut microbial communities from healthy donors can ameliorate airway hyperresponsiveness, reduce eosinophilic infiltration and normalize intestinal microbial diversity in murine asthma models, largely through the enhancement of SCFAs synthesis and expansion of regulatory T-cell populations [156]. Clinical evidence remains preliminary, with only limited human data and no proven efficacy in asthma management. Research on helminth-derived molecules shows immunoregulatory activity through suppression of Th2/Th17 inflammation, induction of IL-10-producing Tregs and modulation of TLR-mediated signaling [157,158].

4. Microbiota in Atherosclerosis

4.1. Role of the Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Disease

4.2. Microbial Metabolites Implicated in Atherosclerosis

- SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) are major fermentation products of dietary fiber in the gut [164]. SCFAs exert pleiotropic cardiovascular effects, improving endothelial function and blood pressure control while attenuating systemic inflammation [164,165]. Recent studies indicate that increasing SCFAs levels attenuate risk factors for atherosclerosis by promoting eubiosis and reinforcing intestinal barrier integrity [164,165,166]. Dysregulation of acetyl-CoA metabolism, essential for SCFA synthesis, has been reported in hypertensive individuals, whereas Bacteroides acidifaciens-derived acetate and propionate have shown cardioprotective effects [167,168]. Likewise, butyrate-producing bacteria such as Roseburia intestinalis reduce vascular inflammation and ACVD by preserving mucosal integrity and limiting systemic endotoxin translocation [169,170]. SCFAs act primarily via G-protein-coupled receptors (OLFR78, GPR41 and GPR43) that regulate vascular tone and immune balance [148,171]. Propionate signaling through GPR41/OLFR78 elicits antihypertensive effects, whereas butyrate and acetate enhance nitric oxide bioavailability, supporting endothelial homeostasis [171,172,173]. High dietary fiber intake correlates with lower blood pressure and improved vascular outcomes in humans, in part due to the anti-inflammatory activity of SCFAs [174]. Butyrate maintains epithelial barrier integrity and inhibits histone deacetylases, leading to epigenetic suppression of pro-inflammatory mediators, thereby reducing cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α in experimental models [175,176,177]. However, excessive circulating SCFA levels, especially under high-protein/high-fiber diets, have been associated with unfavorable lipid profiles, indicating that SCFA effects depend on dietary composition and microbial context [178].

- TMAO represents one of the most extensively characterized gut–vascular co-metabolites [179]. Formed from choline, L-carnitine and phosphatidylcholine via microbial trimethylamine (TMA) synthesis and hepatic oxidation, elevated TMAO levels consistently correlate with higher atherosclerotic burden and cardiovascular risk [163,179]. Meta-analyses of large cohorts (>26,000 participants) reveal a dose-dependent association between TMAO and adverse cardiovascular outcomes [179,180]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that transplanting TMAO-producing microbiota into ApoE−/− mice accelerates plaque development, while TMAO suppression reverses these effects [181,182]. TMAO formation is diet-dependent, with omnivorous diets producing more TMAO than vegetarian or vegan diets [182]. Mechanistically, TMAO promotes atherosclerosis through foam cell formation, platelet hyperreactivity and increased inflammatory signaling [164,177,179]. Elevated TMAO levels associate with upregulated C-reactive protein, IL-1β and vascular nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) activation, contributing to plaque instability [177,179,183]. Microbial enzyme TMA lyase inhibition has shown promise in reducing TMAO-driven vascular injury [184,185].

- Bile acids (BAs) are another class of microbiota-influenced metabolites. They are saturated or hydroxylated steroids that aid absorption of dietary fats, lipophilic vitamins and metabolic regulation of lipids, glucose and systemic metabolic signaling [163,164,186]. Gut microbiota convert hepatic primary BAs into secondary BAs through deconjugation and dehydroxylation reactions, largely involving Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Enterococcus and Clostridium spp. [164,177]. BA signaling through Farnesoid X-activated receptors (FXR) and G-protein-coupled bile acid receptors (TGR5) modulates cholesterol biosynthesis and inflammatory pathways relevant to CVD [177,187]. FXR activation regulates lipid metabolism and flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), a key enzyme in TMAO synthesis, whereas TGR5 activation exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects via nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) inhibition [188]. In contrast, pregnane X receptor (PXR) signaling may enhance macrophage CD36 expression and lipid uptake, promoting plaque growth [189]. Emerging data point to altered bile acid profiles and gut microbiota-derived LPS/leaky gut endotoxaemia as additional mechanisms linking microbial ecology to vascular inflammation and cholesterol metabolism [177].

- Emerging evidence suggests that, in addition to hepatic bile acid synthesis, the gut microbiota actively participates in cholesterol metabolism by converting dietary or endogenous cholesterol into coprostanol, a sterol that is poorly absorbed and therefore eliminated in feces [177,190]. This transformation is primarily mediated by bacterial species from the Eubacterium and Bacteroides genera, such as E. coprostanoligenes and Bacteroides strain D8, although other microbial contributors are likely yet to be identified [190]. Experimental studies in animal models have shown that supplementation with coprostanol-producing bacteria can substantially lower plasma cholesterol concentrations, with effects persisting for several weeks after treatment discontinuation [191]. In contrast, human investigations remain inconclusive due to small study populations, limited microbial isolation success and demographic variability [192]. Moreover, the specific microbial genes and enzymes driving intestinal cholesterol conversion are not fully defined, emphasizing the need for further mechanistic studies to clarify the role of these pathways in cholesterol regulation and cardiovascular protection [192].

- Additional microbial metabolites, including succinate, imidazole propionate (ImP) and tryptophan (Trp) derivatives, also modulate vascular inflammation. Succinate acts as a pro-inflammatory ligand for SUCNR1/GPR91, stimulating HIF-1α, IL-1β and ROS generation [177,193]. Elevated serum succinate correlates with coronary inflammation and enhanced NLRP3 inflammasome activation, linking metabolic stress to vascular damage [177,194]. Similarly, ImP, produced from histidine by specific Clostridioides species, interferes with insulin and AMPK signaling, promoting endothelial dysfunction and metabolic inflammation [179,195]. Finally, Trp metabolism yields multiple bioactive compounds, such as indole-3-propionic acid (IPA) and kynurenine pathway intermediates, that engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling to regulate macrophage activity and immune tolerance [196,197,198,199]. Reduced IPA and Peptostreptococcus-mediated Trp conversion correlate with impaired ABCA1/miR-142-5p signaling, increased foam-cell formation and aggravated atherosclerosis [199].

4.3. Microbial Taxa of Interest

- Gut microbiome: An elevated Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, indicative of dysbiosis, has been recurrently observed in patients with atherosclerotic disease and associated metabolic comorbidities [159]. Taxa in the Enterobacteriaceae family (e.g., Escherichia coli) are enriched in atherosclerosis and correlate with pro-inflammatory gene expression [200]. Veillonella and Streptococcus spp., which appear enriched in plaque samples and peripheral circulation, are emerging as potential biomarkers of atherogenic microbiota [201,202,203].

- Oral microbiome: Periodontal pathogens including Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans have been linked to vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis through mechanisms such as molecular mimicry, direct invasion of vascular tissues and induction of systemic inflammatory responses [40,204,205,206,207].

5. Shared Mechanisms Linking Allergic Asthma and Atherosclerosis via Microbiota

5.1. Dysbiosis as a Common Inflammatory Driver

5.2. Microbial Metabolites Bridging Lung and Vascular Physiopathology

5.3. Convergent Immune and Cytokine Pathways

5.4. Microbial Signatures Across Respiratory and Vascular Systems

5.5. Integrative Concept: The Gut–Lung–Vascular Axis

| Condition | Key Microbial Taxa | Key Metabolites | Functional Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic Asthma | Haemophilus Moraxella Streptococcus | - | Enriched in airway microbiomes of children with asthma; associated with wheezing/exacerbations and disease severity. | [229] |

| - | SCFAs (butyrate, acetate, propionate) | Linked with protection against allergic disease and dampen airway inflammation via Tregs/MDSCs. | [31,146] | |

| Clostridia Bacteroidetes | SCFAs | Early-life depletion of SCFA-producing taxa is associated with atopy/asthma; restoration is protective. | [31] | |

| Bifidobacterium Lachnospira Veillonella Faecalibacterium | SCFAs lactate | Lower early-life abundance of these gut commensals predicts increased risk of wheezing and childhood asthma; their presence supports epithelial barrier integrity and tolerogenic immune programming. | [237] | |

| - | Tryptophan metabolites (indole-3-carbinol, indole-3-acetic acid, kynurenine) | Activate AhR pathways to reduce airway inflammation and improve asthma outcomes. | [238] | |

| - | Secondary bile acids | Bile acid-FXR/TGR5 signaling modulates lung immunity and suppresses type-2 inflammation. | [28] | |

| Atherosclerosis | Firmicutes Bacteroidetes | SCFAs | SCFAs exert anti-inflammatory and vascular-protective effects; reduced SCFA tone linked to CVD risk. | [239] |

| Enterobacteriaceae | TMAO | Microbial conversion of choline/carnitine to TMAO promotes atherosclerosis and adverse cardiovascular events. | [240] | |

| Streptococcus Veilonella Porphyromonas gingivalis | LPS | Oral taxa present in plaques; endotoxin signaling (TLR4) drives vascular inflammation and lesion progression. | [201,230] | |

| Enterobacteriaceae Clostridia | Secondary bile acids | Microbiota-modified bile acids regulate lipid metabolism and vascular inflammation via FXR/TGR5 pathways. | [239] | |

| Aromatic amino acid–metabolizing gut consortia | Phenylacetylglutamine (PAGln) | PAGln, derived from microbial phenylalanine metabolism, enhances platelet reactivity through adrenergic receptors and is associated with higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events. | [241,242] |

| Study (Year) | Model/ Population | Main Findings | Key Microbial/ Metabolic Changes | Proposed Mechanisms/ Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim YC et al. (2024) [32] | Human cohort review | Provides overview of clinical and experimental evidence demonstrating that gut microbial imbalance correlates with asthma severity and exacerbations. | Depletion of SCFA-producers (Faecalibacterium, Roseburia); lower fecal SCFAs. | ↓ SCFAs → impaired Treg induction, enhancedTh2 inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. |

| Boulund U. et al. (2025) [93] | Review (focus on early-life cohorts) | Microbial exposures during infancy and early gut colonization patterns are strong determinants of subsequent asthma susceptibility | ↓ Bifidobacterium and other early colonizers; disrupted microbial succession during the first months of life. | Early dysbiosis interferes with immune maturation → higher allergic sensitization and increased risk of childhood asthma. |

| Zheng XW et al. (2024) [243] | Human cohort/genetics integration (Mendelian randomization) | Identified genetic links between gut microbial traits and asthma risk; complex taxa associations (some complex and sometimes inconsistent associations across taxa). | Context-dependent patterns, including reduced abundance of certain SCFA-producing genera but variable signals for taxa (e.g., Roseburia). | Indicates that host–microbe interactions in asthma are multifactorial and cannot be reduced to simple, linear taxon-to-effect relationships. |

| Ramar et al. (2025) [244] | Mechanistic humanized/cell-report studies | Provide emerging causal evidence that defined gut microbial communities can shape susceptibility to asthma, particularly when hosts are exposed to environmental particulate triggers. | Specific live bacterial consortia were shown to modulate airway inflammatory responses in colonized hosts. | Supports causality: gut microbes can prime lung immunity through epigenetic pathways, such as DNA methylation changes in dendritic cells, thereby driving asthma-like phenotypes. |

| Study (Year) | Model/ Population | Main Findings | Key Microbial/ Metabolic Changes | Proposed Mechanisms/ Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu Y. et al. (2020) [245] | Review integrating experimental and preclinical evidence | Proposed central role of TMA/TMAO pathway and other metabolites in promoting endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis. | ↑ TMAO levels associated with increased activity of TMA-producing taxa such as Clostridia and Desulfovibrio, together with disruptions in BA metabolism. | TMAO enhances foam cell formation, promotes vascular inflammation and contributes to pro-thrombotic remodeling of the vessel wall. |

| Li X. et al. (2021) [246] | ApoE−/− mouse model | Antibiotic treatment or targeted modulation of the gut microbiota can alter atherosclerotic plaque burden by influencing TMA/TMAO production. | ↓ TMA-generating bacterial taxa accompanied by decreased circulating TMAO levels. | Lower TMAO limits macrophage foam cell formation and vascular inflammatory pathways → smaller atherosclerotic lesions. |

| Pala B. et al. (2024) [247] | Human carotid intima–media thickness (IMT) cohort | Gut microbiome composition correlated with carotid IMT and plaque characteristics, linking microbial patterns to early vascular remodeling. | ↑ Prevotella spp., altered Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratios; ↑ LPS-associated microbial pathways. | Microbially derived LPS and related metabolites correlate with endothelial dysfunction and markers of subclinical atherosclerosis. |

| Mao Y. et al. (2024) [165] | Review/multi-study synthesis | Integrative overview of how gut microbial alterations contribute to different stages of atherosclerosis, emphasizing the role of key microbial metabolites (TMAO, SCFAs, BA). | ↓ SCFAs (anti-inflammatory), ↑ TMAO and specific BA derivatives in patients with increased cardiovascular risk. | Metabolite shifts modulate vascular inflammation, lipid metabolism and immune cell recruitment, thereby shaping atherosclerotic disease progression. |

| Jarmukhanov Z. et al. (2024) [248] | Systematic review/meta-analysis | ↑ TMAO consistently associated with higher CVD and atherosclerosis risk across multiple human cohorts. | ↑ circulating TMAO across cohorts; microbial taxa linked to TMA production (e.g., Escherichia/Shigella, Klebsiella). | Supports the concept of a microbe–metabolite–vascular risk pathway, with TMAO emerging as a prognostic biomarker for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. |

| Zhou Y. et al. (2024) [249] | Mechanistic review/multi-omics | Multi-omics evidence links gut microbial metabolome (TMAO, BA) to vascular NF-κB and inflammasome activation. | ↑ TMAO and pro-inflammatory BA; ↓ protective SCFAs. | Activation of endothelial inflammatory signaling (NF-κB, NLRP3) → plaque development, progression and destabilization. |

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wecker, H.; Tizek, L.; Ziehfreund, S.; Kain, A.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Zimmermann, G.S.; Scala, E.; Elberling, J.; Doll, A.; Boffa, M.J.; et al. Impact of Asthma in Europe: A Comparison of Web Search Data in 21 European Countries. World Allergy Organ. J. 2023, 16, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, K.; Bansal, V.; Mahmood, R.; Kanagala, S.G.; Jain, R. Asthma and Cardiovascular Diseases: Uncovering Common Ground in Risk Factors and Pathogenesis. Cardiol. Rev. 2025, 33, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, T. Asthma as Risk for Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Its Subtypes. Hypertens. Res. 2023, 46, 2056–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbru, R.-I.; Zimbru, E.-L.; Bojin, F.-M.; Haidar, L.; Andor, M.; Harich, O.O.; Tănasie, G.; Tatu, C.; Mailat, D.-E.; Zbîrcea, I.-M.; et al. Connecting the Dots: How MicroRNAs Link Asthma and Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, M.C.; Guo, M.; Korcarz, C.E.; Gepner, A.D.; Kaufman, J.D.; Liu, K.J.; Barr, R.G.; Donohue, K.M.; McClelland, R.L.; Delaney, J.A.; et al. Asthma Predicts Cardiovascular Disease Events: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazzola, M.; Hanania, N.A.; Rogliani, P.; Matera, M.G. Cardiovascular Disease in Asthma Patients: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implications. Kardiol. Pol. 2023, 81, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, X.; Yu, D.; Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shen, Y. Asthma and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2025, 19, 17534666251333965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Z.-F.; An, Z.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.-Y.; Hao, M.-D.; Jin, Y.-J.; Li, D.; Song, A.-J.; Ren, Q.; et al. Association Between Asthma and All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease Morbidity and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 861798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Samarraie, A.; Pichette, M.; Rousseau, G. Role of the Gut Microbiome in the Development of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Hu, H.; Hu, J.; Liu, M.; Yang, Q.; Gu, P.; Li, J.; et al. Gut–X Axis. iMeta 2025, 4, e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.M.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.S.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V.; et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Waters, J.L.; Poole, A.C.; Sutter, J.L.; Koren, O.; Blekhman, R.; Beaumont, M.; Van Treuren, W.; Knight, R.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Human Genetics Shape the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2014, 159, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.K.; Ye, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Xia, Y.; Wong, S.H.-S.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y. Exercised Gut Microbiota Improves Vascular and Metabolic Abnormalities in Sedentary Diabetic Mice through Gut-vascular Connection. J. Sport Health Sci. 2025, 14, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, X.; Shi, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, K.; Wang, S. Gut Microbiota Regulate Atherosclerosis via the Gut-Vascular Axis: A Scoping Review of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1606309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandrescu, L.; Suceveanu, A.P.; Stanigut, A.M.; Tofolean, D.E.; Axelerad, A.D.; Iordache, I.E.; Herlo, A.; Nelson Twakor, A.; Nicoara, A.D.; Tocia, C.; et al. Intestinal Insights: The Gut Microbiome’s Role in Atherosclerotic Disease: A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.E.; Vargas, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, T.; Encío, I.J.; Cabello-Olmo, M.; Barajas, M. Human Microbiota Network: Unveiling Potential Crosstalk between the Different Microbiota Ecosystems and Their Role in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Shukla, S.D.; Rehman, S.F.; Bowerman, K.L.; Keely, S.; Hugenholtz, P.; Armstrong-James, D.P.H.; Adcock, I.M.; Chotirmall, S.H.; Chung, K.F.; et al. Functional Effects of the Microbiota in Chronic Respiratory Disease. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Zhou, G.; Chen, R.; Bai, C.; Shi, F. Innovative Therapeutic Strategies for Asthma: The Role of Gut Microbiome in Airway Immunity. J. Asthma Allergy 2025, 18, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Yao, H.; Wei, P. Advances in Research on Gut Microbiota and Allergic Diseases in Children. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 8, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colucci, R.; Moretti, S. Implication of Human Bacterial Gut Microbiota on Immune-Mediated and Autoimmune Dermatological Diseases and Their Comorbidities: A Narrative Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 11, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, F. Role of Intestinal Microbiota on Gut Homeostasis and Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 8167283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, K. Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Multiple Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttiah, B.; Hanafiah, A. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Diseases: Unraveling the Role of Dysbiosis and Microbial Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogal, A.; Valdes, A.M.; Menni, C. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Interplay between Gut Microbiota and Diet in Cardio-Metabolic Health. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1897212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Pei, C.; Peng, W.; Zheng, Y.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Microbiota-Derived Butyrate Alleviates Asthma via Inhibiting Tfh13-Mediated IgE Production. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druszczynska, M.; Sadowska, B.; Kulesza, J.; Gąsienica-Gliwa, N.; Kulesza, E.; Fol, M. The Intriguing Connection Between the Gut and Lung Microbiomes. Pathogens 2024, 13, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, K.; Yang, D. Gut-Lung Axis Mediates Asthma Pathogenesis: Roles of Dietary Patterns and Their Impact on the Gut Microbiota. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2025, 142, 104964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suslov, A.V.; Panas, A.; Sinelnikov, M.Y.; Maslennikov, R.V.; Trishina, A.S.; Zharikova, T.S.; Zharova, N.V.; Kalinin, D.V.; Pontes-Silva, A.; Zharikov, Y.O. Applied Physiology: Gut Microbiota and Antimicrobial Therapy. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 124, 1631–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ney, L.-M.; Wipplinger, M.; Grossmann, M.; Engert, N.; Wegner, V.D.; Mosig, A.S. Short Chain Fatty Acids: Key Regulators of the Local and Systemic Immune Response in Inflammatory Diseases and Infections. Open Biol. 2023, 13, 230014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Suaini, N.H.A.; Afghani, J.; Heye, K.N.; O’Mahony, L.; Venter, C.; Lauener, R.; Frei, R.; Roduit, C. Systematic Review of the Association between Short-chain Fatty Acids and Allergic Diseases. Allergy 2024, 79, 1789–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-C.; Sohn, K.-H.; Kang, H.-R. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Its Impact on Asthma and Other Lung Diseases: Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 746–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagiakrishnan, K.; Morgadinho, J.; Halverson, T. Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Dysbiosis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1330903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleniewska, P.; Pawliczak, R. The Link Between Dysbiosis, Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Asthma—The Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Antioxidants. Nutrients 2024, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, H.; Kuwahara, Y.; Takahashi, K. Gut–Lung Axis in Asthma and Obesity: Role of the Gut Microbiome. Front. Allergy 2025, 6, 1618466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the Human Gut Microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, A.; Marchesi, N.; Marelli, C.; Coppola, A.; Luzi, L.; Govoni, S.; Giustina, A.; Gazzaruso, C. Microbiota and Metabolic Diseases. Endocrine 2018, 61, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego-Ruiz, A.; Borrego, J.J. Early-Life Gut Microbiome Development and Its Potential Long-Term Impact on Health Outcomes. Microbiome Res. Rep. 2025, 4, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Edwards, D.J.; Spaine, K.M.; Edupuganti, L.; Matveyev, A.; Serrano, M.G.; Buck, G.A. The Association of Maternal Factors with the Neonatal Microbiota and Health. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Xie, X.; Wu, Q. Gut Microbiota: A Novel Strategy Affecting Atherosclerosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e00482-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Angarita, L.; Morillo, V.; Navarro, C.; Martínez, M.S.; Chacín, M.; Torres, W.; Rajotia, A.; Rojas, M.; Cano, C.; et al. Microbiota and Diabetes Mellitus: Role of Lipid Mediators. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espírito Santo, C.; Caseiro, C.; Martins, M.J.; Monteiro, R.; Brandão, I. Gut Microbiota, in the Halfway between Nutrition and Lung Function. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durack, J.; Lynch, S.V. The Gut Microbiome: Relationships with Disease and Opportunities for Therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malesza, I.J.; Malesza, M.; Walkowiak, J.; Mussin, N.; Walkowiak, D.; Aringazina, R.; Bartkowiak-Wieczorek, J.; Mądry, E. High-Fat, Western-Style Diet, Systemic Inflammation, and Gut Microbiota: A Narrative Review. Cells 2021, 10, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Costello, E.K.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Stombaugh, J.; Knights, D.; Gajer, P.; Ravel, J.; Fierer, N.; et al. Moving Pictures of the Human Microbiome. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremaroli, V.; Bäckhed, F. Functional Interactions between the Gut Microbiota and Host Metabolism. Nature 2012, 489, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on Health and Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Wolters, M.; Weyh, C.; Krüger, K.; Ticinesi, A. The Effects of Lifestyle and Diet on Gut Microbiota Composition, Inflammation and Muscle Performance in Our Aging Society. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D.; Petitfils, C.; De Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; El-Omar, E.M. What Defines a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gut 2024, 73, 1893–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Maiti, T.K.; Mahajan, D.; Das, B. Human Gut Microbiota and Drug Metabolism. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowen, R.; Gamal, A.; Di Martino, L.; McCormick, T.S.; Ghannoum, M.A. Modulating the Microbiome for Crohn’s Disease Treatment. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Bays, D.J.; Savage, H.P.; Bäumler, A.J. The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease: Time for a New Chapter? Infect. Immun. 2024, 92, e00302-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonetti, T.; Saggioratto, M.C.; Grande, A.J.; Colonetti, L.; Junior, J.C.D.; Ceretta, L.B.; Roever, L.; Silva, F.R.; Da Rosa, M.I. Gut and Vaginal Microbiota in the Endometriosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 2675966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldán, M.; Argalášová, Ľ.; Hadvinová, L.; Galileo, B.; Babjaková, J. The Effect of Dietary Types on Gut Microbiota Composition and Development of Non-Communicable Diseases: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merra, G.; Noce, A.; Marrone, G.; Cintoni, M.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Capacci, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Influence of Mediterranean Diet on Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Chierico, F.; Vernocchi, P.; Dallapiccola, B.; Putignani, L. Mediterranean Diet and Health: Food Effects on Gut Microbiota and Disease Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 11678–11699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagpal, R.; Shively, C.A.; Register, T.C.; Craft, S.; Yadav, H. Gut Microbiome-Mediterranean Diet Interactions in Improving Host Health. F1000Research 2019, 8, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Bibiloni, R.; Knauf, C.; Waget, A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Burcelin, R. Changes in Gut Microbiota Control Metabolic Endotoxemia-Induced Inflammation in High-Fat Diet–Induced Obesity and Diabetes in Mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuke, N.; Nagata, N.; Suganuma, H.; Ota, T. Regulation of Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Endotoxemia with Dietary Factors. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamun, M.A.A.; Rakib, A.; Mandal, M.; Singh, U.P. Impact of a High-Fat Diet on the Gut Microbiome: A Comprehensive Study of Microbial and Metabolite Shifts During Obesity. Cells 2025, 14, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Dong, H.; Chen, Z.; Jin, M.; Yin, J.; Li, H.; Shi, D.; Shao, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota Mediates High-Fructose and High-Fat Diets to Induce Chronic Intestinal Inflammation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 654074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomova, A.; Bukovsky, I.; Rembert, E.; Yonas, W.; Alwarith, J.; Barnard, N.D.; Kahleova, H. The Effects of Vegetarian and Vegan Diets on Gut Microbiota. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rew, L.; Harris, M.D.; Goldie, J. The Ketogenic Diet: Its Impact on Human Gut Microbiota and Potential Consequent Health Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2022, 15, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gong, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X. Ketogenic Diet and Gut Microbiota: Exploring New Perspectives on Cognition and Mood. Foods 2025, 14, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Bäckhed, F. The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.N.; Walsh, C.J.; Maiden, M.J.; Stinear, T.P.; Deane, A.M. Effect of Dietary Fibre on the Gastrointestinal Microbiota during Critical Illness: A Scoping Review. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2025, 14, 98241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W. Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Van Treuren, W.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-Microbiota-Targeted Diets Modulate Human Immune Status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuwendaal, N.K.; Stanton, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Beresford, T.P. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, W. Drug-Microbiota Interactions: An Emerging Priority for Precision Medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Shi, Y.; Qiao, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Multi-Omics Study Reveals That Statin Therapy Is Associated with Restoration of Gut Microbiota Homeostasis and Improvement in Outcomes in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5778–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Sun, L.; Yu, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhuo, X.; Guo, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; et al. A Gut Feeling of Statin. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2415487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lan, Q.; Deng, H.; Han, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhong, J. Interactions between Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Drugs: Effects on Drug Therapeutic Effect and Side Effect. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1570008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbru, R.-I.; Grijincu, M.; Tănasie, G.; Zimbru, E.-L.; Bojin, F.-M.; Buzan, R.-M.; Tamaș, T.-P.; Cotarcă, M.-D.; Harich, O.O.; Pătrașcu, R.; et al. Breaking Barriers: The Detrimental Effects of Combined Ragweed and House Dust Mite Allergen Extract Exposure on the Bronchial Epithelium. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Mousa, W.K. The Interplay between Gut Microbiota and Oral Medications and Its Impact on Advancing Precision Medicine. Metabolites 2023, 13, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltak, S.N.; Steen, T.Y. The Impact of Antibiotic Use on the Human Gut Microbiome: A Review. Georget. Med. Rev. 2025, 143628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patangia, D.V.; Anthony Ryan, C.; Dempsey, E.; Paul Ross, R.; Stanton, C. Impact of Antibiotics on the Human Microbiome and Consequences for Host Health. MicrobiologyOpen 2022, 11, e1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ju, D.; Zeng, X. Mechanisms and Clinical Implications of Human Gut Microbiota-Drug Interactions in the Precision Medicine Era. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyte Sjödin, K.; Vidman, L.; Rydén, P.; West, C.E. Emerging Evidence of the Role of Gut Microbiota in the Development of Allergic Diseases. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 16, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.Y.; Inoue, T.; Leone, V.A.; Dalal, S.; Touw, K.; Wang, Y.; Musch, M.W.; Theriault, B.; Higuchi, K.; Donovan, S.; et al. Using Corticosteroids to Reshape the Gut Microbiome: Implications for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Tian, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Ma, S. Effects of High-Dose Glucocorticoids on Gut Microbiota in the Treatment of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e02467-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcik, W.; Boutin, R.C.T.; Sokolowska, M.; Finlay, B.B. The Role of Lung and Gut Microbiota in the Pathology of Asthma. Immunity 2020, 52, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Qin, Z.; Huang, C.; Liang, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, W. The Gut Microbiota Modulates Airway Inflammation in Allergic Asthma through the Gut-Lung Axis Related Immune Modulation: A Review. Biomol. Biomed. 2024, 25, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, J. Gut-Lung Axis in Allergic Asthma: Microbiota-Driven Immune Dysregulation and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1617546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhann, F.; Bonder, M.J.; Vich Vila, A.; Fu, J.; Mujagic, Z.; Vork, L.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Jankipersadsing, S.A.; Cenit, M.C.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Affect the Gut Microbiome. Gut 2016, 65, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Xia, S.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Xiao, X. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Oral–Gut Microbiota: From Mechanism to Clinical Significance. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-B.; Chu, X.-J.; Cao, N.-W.; Wang, H.; Fang, X.-Y.; Fan, Y.-G.; Li, B.-Z.; Ye, D.-Q. Proton Pump Inhibitors Induce Changes in the Gut Microbiome Composition of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuteja, S.; Ferguson, J.F. Gut Microbiome and Response to Cardiovascular Drugs. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2019, 12, e002314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Hu, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, L.; Wu, M. Targets of Statins Intervention in LDL-C Metabolism: Gut Microbiota. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 972603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bastard, Q.; Berthelot, L.; Soulillou, J.-P.; Montassier, E. Impact of Non-Antibiotic Drugs on the Human Intestinal Microbiome. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn 2021, 21, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skillington, O.; Mills, S.; Gupta, A.; Mayer, E.A.; Gill, C.I.R.; Del Rio, D.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cryan, J.F.; Ross, R.P.; Stanton, C. The Contrasting Human Gut Microbiota in Early and Late Life and Implications for Host Health and Disease. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2021, 6, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattaroni, C.; Marsland, B.J.; Harris, N.L. Early-Life Host–Microbial Interactions and Asthma Development: A Lifelong Impact? Immunol. Rev. 2025, 330, e70019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulund, U.; Thorsen, J.; Trivedi, U.; Tranæs, K.; Jiang, J.; Shah, S.A.; Stokholm, J. The Role of the Early-Life Gut Microbiome in Childhood Asthma. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2457489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E.; Haran, J. The Human Gut Microbiome and Aging. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2359677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, M.; Rio, P.; Marrone, A.; Giambra, V.; Gasbarrini, A.; Gambassi, G.; Cianci, R. Inflammaging: The Next Challenge—Exploring the Role of Gut Microbiota, Environmental Factors, and Sex Differences. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, Q.; Duan, R.; Ma, X.; Li, L.; Shu, Z.; Miao, Y.; Shen, H.; Lv, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiome Dynamics and Functional Shifts in Healthy Aging: Insights from a Metagenomic Study. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1629811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, G.; Gloor, G.B.; Gong, A.; Jia, C.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. The Gut Microbiota of Healthy Aged Chinese Is Similar to That of the Healthy Young. mSphere 2017, 2, e00327-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, E.N.; Surette, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M.E. The Gut Microbiota and Unhealthy Aging: Disentangling Cause from Consequence. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Torralba, M.G.; Moncera, K.J.; DiLello, L.; Petrini, J.; Nelson, K.E.; Pieper, R. Gastro-Intestinal and Oral Microbiome Signatures Associated with Healthy Aging. GeroScience 2019, 41, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, J.P.; Bucci, V.; Dutta, P.; Ward, D.; McCormick, B. The Nursing Home Elder Microbiome Stability and Associations with Age, Frailty, Nutrition and Physical Location. J. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 67, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, J.P.; Bhattarai, S.K.; Foley, S.E.; Dutta, P.; Ward, D.V.; Bucci, V.; McCormick, B.A. Alzheimer’s Disease Microbiome Is Associated with Dysregulation of the Anti-Inflammatory P-Glycoprotein Pathway. mBio 2019, 10, e00632-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemis, J.H.; Linke, V.; Barrett, K.L.; Boehm, F.J.; Traeger, L.L.; Keller, M.P.; Rabaglia, M.E.; Schueler, K.L.; Stapleton, D.S.; Gatti, D.M.; et al. Genetic Determinants of Gut Microbiota Composition and Bile Acid Profiles in Mice. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzior, D.V.; Quinn, R.A. Review: Microbial Transformations of Human Bile Acids. Microbiome 2021, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubier, J.A.; Chesler, E.J.; Weinstock, G.M. Host Genetic Control of Gut Microbiome Composition. Mamm. Genome 2021, 32, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieneisen, L.; Dasari, M.; Gould, T.J.; Björk, J.R.; Grenier, J.-C.; Yotova, V.; Jansen, D.; Gottel, N.; Gordon, J.B.; Learn, N.H.; et al. Gut Microbiome Heritability Is Nearly Universal but Environmentally Contingent. Science 2021, 373, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurilshikov, A.; Medina-Gomez, C.; Bacigalupe, R.; Radjabzadeh, D.; Wang, J.; Demirkan, A.; Le Roy, C.I.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; Finnicum, C.T.; Liu, X.; et al. Large-Scale Association Analyses Identify Host Factors Influencing Human Gut Microbiome Composition. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, M.; Di Salvo, E.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Microbiota and microRNAs in Lung Diseases: Mutual Influence and Role Insights. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 13000–13008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaspa, M.; Bassat, Q.; Medeiros, M.M.; Muñoz-Almagro, C. Respiratory Microbiota and Lower Respiratory Tract Disease. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; De Vos, W.M. Infant Gut Microbiota Restoration: State of the Art. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2118811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Nimwegen, F.A.; Penders, J.; Stobberingh, E.E.; Postma, D.S.; Koppelman, G.H.; Kerkhof, M.; Reijmerink, N.E.; Dompeling, E.; Van Den Brandt, P.A.; Ferreira, I.; et al. Mode and Place of Delivery, Gastrointestinal Microbiota, and Their Influence on Asthma and Atopy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 948–955.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edouard, S.; Million, M.; Bachar, D.; Dubourg, G.; Michelle, C.; Ninove, L.; Charrel, R.; Raoult, D. The Nasopharyngeal Microbiota in Patients with Viral Respiratory Tract Infections Is Enriched in Bacterial Pathogens. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.-C.; Stiemsma, L.T.; Dimitriu, P.A.; Thorson, L.; Russell, S.; Yurist-Doutsch, S.; Kuzeljevic, B.; Gold, M.J.; Britton, H.M.; Lefebvre, D.L.; et al. Early Infancy Microbial and Metabolic Alterations Affect Risk of Childhood Asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 307ra152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, K.E.; Sitarik, A.R.; Havstad, S.; Lin, D.L.; Levan, S.; Fadrosh, D.; Panzer, A.R.; LaMere, B.; Rackaityte, E.; Lukacs, N.W.; et al. Neonatal Gut Microbiota Associates with Childhood Multisensitized Atopy and T Cell Differentiation. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1187–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, A.; Gio-Batta, M.; Hesselmar, B.; Imberg, H.; Rabe, H.; Nowrouzian, F.L.; Johansen, S.; Törnhage, C.-J.; Lindhagen, G.; Ceder, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Markers in Early Childhood Are Linked to Farm Living, Pets in Household and Allergy. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtimäki, J.; Thorsen, J.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Hjelmsø, M.; Shah, S.; Mortensen, M.S.; Trivedi, U.; Vestergaard, G.; Bønnelykke, K.; Chawes, B.L.; et al. Urbanized Microbiota in Infants, Immune Constitution, and Later Risk of Atopic Diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.; Lee, S.; Piperata, B.A.; Garabed, R.; Choi, B.; Lee, J. Household Environment and Animal Fecal Contamination Are Critical Modifiers of the Gut Microbiome and Resistome in Young Children from Rural Nicaragua. Microbiome 2023, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Z.; Lei, F.; Liu, W.; Lin, L.; Sun, T.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Cai, J.; Li, H. Association of Urban Environments with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study in the UK Biobank. Environ. Int. 2024, 193, 109110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.R.G.; Baptiste, P.J.; Hajmohammadi, H.; Nadarajah, R.; Gale, C.P.; Wu, J. Impact of Neighbourhood and Environmental Factors on the Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 32, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, A.-A.; Mornoş, C. The Impact of Meteorological Factors and Air Pollutants on Acute Coronary Syndrome. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2022, 24, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansaldo, E.; Farley, T.K.; Belkaid, Y. Control of Immunity by the Microbiota. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 449–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianci, R.; Franza, L.; Massaro, M.G.; Borriello, R.; Tota, A.; Pallozzi, M.; De Vito, F.; Gambassi, G. The Crosstalk between Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Immunological Niche and Visceral Adipose Tissue as a New Model for the Pathogenesis of Metabolic and Inflammatory Diseases: The Paradigm of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3189–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F.; Barone, M.; Tavella, T.; Rampelli, S.; Brigidi, P.; Turroni, S. Host Microbiomes in Tumor Precision Medicine: How Far Are We? Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3202–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccioni, A.; Cicchinelli, S.; Valletta, F.; De Luca, G.; Longhitano, Y.; Candelli, M.; Ojetti, V.; Sardeo, F.; Navarra, S.; Covino, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Diseases: A Charming Real World Together with Probiotics. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3147–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassini, C.; Zatti, P.H.; Angeli, V.W.; Branco, C.S.; Salvador, M. Mutual Effects of Free and Nanoencapsulated Phenolic Compoundson Human Microbiota. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 3160–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldanzi, G.; Sayols-Baixeras, S.; Ekblom-Bak, E.; Ekblom, Ö.; Dekkers, K.F.; Hammar, U.; Nguyen, D.; Ahmad, S.; Ericson, U.; Arvidsson, D.; et al. Accelerometer-Based Physical Activity Is Associated with the Gut Microbiota in 8416 Individuals in SCAPIS. eBioMedicine 2024, 100, 104989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aya, V.; Jimenez, P.; Muñoz, E.; Ramírez, J.D. Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Gut Microbiota Composition and Function in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotti, S.; Dinu, M.; Colombini, B.; Amedei, A.; Sofi, F. Circadian Rhythms, Gut Microbiota, and Diet: Possible Implications for Health. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 33, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, L.; Gong, C.; Li, T.; Xia, Y. The Diversity of the Intestinal Microbiota in Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder and Its Relationship to Alcohol Consumption and Cognition. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1054685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zeng, G.; Sun, L.; Jiang, C. When Smoke Meets Gut: Deciphering the Interactions between Tobacco Smoking and Gut Microbiota in Disease Development. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Yan, Y.; Webb, R.J.; Li, Y.; Mehrabani, S.; Xin, B.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Mazidi, M. Psychological Stress and Gut Microbiota Composition: A Systematic Review of Human Studies. Neuropsychobiology 2023, 82, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Song, X.; Qian, Y.; Liao, Z.; Sui, L.; Ai, L.; Xia, Y. Understanding the Connection between Gut Homeostasis and Psychological Stress. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N.; Chida, Y.; Aiba, Y.; Sonoda, J.; Oyama, N.; Yu, X.; Kubo, C.; Koga, Y. Postnatal Microbial Colonization Programs the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal System for Stress Response in Mice. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N. Role of Gut Microbiota in Brain Function and Stress-Related Pathology. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2019, 38, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beurel, E. Stress in the Microbiome-Immune Crosstalk. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2327409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofani, G.S.S.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. I “Gut” Rhythm: The Microbiota as a Modulator of the Stress Response and Circadian Rhythms. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 1454–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashique, S.; De Rubis, G.; Sirohi, E.; Mishra, N.; Rihan, M.; Garg, A.; Reyes, R.-J.; Manandhar, B.; Bhatt, S.; Jha, N.K.; et al. Short Chain Fatty Acids: Fundamental Mediators of the Gut-Lung Axis and Their Involvement in Pulmonary Diseases. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, W.; Hughes, M.R.; Li, Y.; Cait, A.; Hirst, M.; Mohn, W.W.; McNagny, K.M. Butyrate Shapes Immune Cell Fate and Function in Allergic Asthma. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 628453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, M.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Shen, S.; You, Y.; Xue, Z. The Role of Gut Microbiome in the Complex Relationship between Respiratory Tract Infection and Asthma. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1219942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenzel, A.; Geiger, A.; Nendel, E.; Yang, Z.; Krammer, S.; Leberle, A.; Brunst, A.-K.; Trump, S.; Mittler, S.; Rauh, M.; et al. Fiber Rich Food Suppressed Airway Inflammation, GATA3 + Th2 Cells, and FcεRIα+ Eosinophils in Asthma. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1367864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Golovko, S.; Golovko, M.Y.; Singh, S.; Darland, D.C.; Combs, C.K. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Short Chain Fatty Acids in the AppNL-G-F Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 76, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hougee, S.; Vriesema, A.J.M.; Wijering, S.C.; Knippels, L.M.J.; Folkerts, G.; Nijkamp, F.P.; Knol, J.; Garssen, J. Oral Treatment with Probiotics Reduces Allergic Symptoms in Ovalbumin-Sensitized Mice: A Bacterial Strain Comparative Study. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 151, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angurana, S.K.; Bansal, A.; Singhi, S.; Aggarwal, R.; Jayashree, M.; Salaria, M.; Mangat, N.K. Evaluation of Effect of Probiotics on Cytokine Levels in Critically Ill Children With Severe Sepsis: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, E.-K.; Chang, W.-W.; Jhong, J.-H.; Tsai, W.-H.; Chou, C.-H.; Wang, I.-J. Lacticaseibacillus Paracasei GM-080 Ameliorates Allergic Airway Inflammation in Children with Allergic Rhinitis: From an Animal Model to a Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Cells 2023, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Bunyavanich, S. Microbial Influencers: The Airway Microbiome’s Role in Asthma. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e184316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbru, R.-I.; Zimbru, E.-L.; Ordodi, V.-L.; Bojin, F.-M.; Crîsnic, D.; Grijincu, M.; Mirica, S.-N.; Tănasie, G.; Georgescu, M.; Huțu, I.; et al. The Impact of High-Fructose Diet and Co-Sensitization to House Dust Mites and Ragweed Pollen on the Modulation of Airway Reactivity and Serum Biomarkers in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-T.; Chiu, C.-J.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Lee, Y.-R.; Liu, W.-L.; Chuang, H.-L.; Huang, M.-T. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Ameliorate Allergic Airway Inflammation via Sequential Induction of PMN-MDSCs and Treg Cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Glob. 2023, 2, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shibata, R.; Sato, N.; Jinnohara, T.; Suzuki, S.; Suda, W.; Hattori, M.; Kimura, I.; Nakano, T.; et al. The Propionate-GPR41 Axis in Infancy Protects from Subsequent Bronchial Asthma Onset. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2206507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shao, J.; Liao, Y.-T.; Wang, L.-N.; Jia, Y.; Dong, P.; Liu, Z.; He, D.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Regulation of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1186892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Han, B.; Hou, Y.; Ai, X. Microbial Short Chain Fatty Acids: Effective Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors in Immune Regulation (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med 2025, 57, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Zhong, C.; Bao, S.; Wei, K.; Wang, W.; Li, N.; Bai, C.; Chen, W.; Tang, H. Impaired Tryptophan Metabolism by Type 2 Inflammation in Epithelium Worsening Asthma. iScience 2024, 27, 109923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, D.; Baral, T.; Manu, M.K.; Mohapatra, A.K.; Miraj, S.S. Efficacy of Probiotics as Adjuvant Therapy in Bronchial Asthma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2024, 20, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; Cioffi, L.; Giuliano, M.; Pane, M.; Ciprandi, G.; The PROPAM Study Group. A Post Hoc Analysis on the Effects of a Probiotic Mixture on Asthma Exacerbation Frequency in Schoolchildren. ERJ Open Res. 2022, 8, 00020–02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Yuan, G.; Li, C.; Xiong, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, X. High Cellulose Dietary Intake Relieves Asthma Inflammation through the Intestinal Microbiome in a Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdona, E.; Ekström, S.; Andersson, N.; Håkansson, N.; Wolk, A.; Westman, M.; Van Hage, M.; Kull, I.; Melén, E.; Bergström, A. Dietary Fibre in Relation to Asthma, Allergic Rhinitis and Sensitization from Childhood up to Adulthood. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2022, 12, e12188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębińska, A.; Sozańska, B. Fermented Food in Asthma and Respiratory Allergies—Chance or Failure? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Qiu, R.; Zhou, J.; Ren, L.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, G. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Alleviates Airway Inflammation in Asthmatic Rats by Increasing the Level of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Intestine. Inflammation 2025, 48, 1538–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, P.; Aravindhan, V.; Mukherjee, S. Helminth-Derived Biomacromolecules as Therapeutic Agents for Treating Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases: What Lessons Do We Get from Recent Findings? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feary, J.R.; Venn, A.J.; Mortimer, K.; Brown, A.P.; Hooi, D.; Falcone, F.H.; Pritchard, D.I.; Britton, J.R. Experimental Hookworm Infection: A Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial in Asthma. Clin Exp. Allergy 2010, 40, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.V.A.; Hwangbo, H.; Lai, Y.; Hong, S.B.; Choi, Y.-J.; Park, H.-J.; Ban, K. The Gut-Heart Axis: Updated Review for The Roles of Microbiome in Cardiovascular Health. Korean Circ. J. 2023, 53, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, R.; Chen, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, F.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.; Fang, F.; Li, Y.; Shen, X. Characterization of Gut Microbiota in Adults with Coronary Atherosclerosis. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonch-Cerbu, A.-K.; Boicean, A.-G.; Stoia, O.-M.; Teodoru, M. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Atherosclerosis: Pathways, Biomarkers, and Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Zang, G.; Zhang, L.; Shao, C.; Wang, Z. Gut Microbiota and Atherosclerosis—Focusing on the Plaque Stability. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 668532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.; Weeks, T.L.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Gérard, P. Diet-Gut Microbiota Interactions on Cardiovascular Disease. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1528–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Kong, C.; Zang, T.; You, L.; Wang, L.; Shen, L.; Ge, J. Impact of the Gut Microbiome on Atherosclerosis. mLife 2024, 3, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; He, C.; An, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Shan, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. The Role of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Body Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaric, B.L.; Radovanovic, J.N.; Gluvic, Z.; Stewart, A.J.; Essack, M.; Motwalli, O.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Atherosclerosis Linked to Aberrant Amino Acid Metabolism and Immunosuppressive Amino Acid Catabolizing Enzymes. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 551758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.Z.; Nelson, E.; Chu, P.-Y.; Horlock, D.; Fiedler, A.; Ziemann, M.; Tan, J.K.; Kuruppu, S.; Rajapakse, N.W.; El-Osta, A.; et al. High-Fiber Diet and Acetate Supplementation Change the Gut Microbiota and Prevent the Development of Hypertension and Heart Failure in Hypertensive Mice. Circulation 2017, 135, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, K.; Krautkramer, K.A.; Org, E.; Romano, K.A.; Kerby, R.L.; Vivas, E.I.; Mehrabian, M.; Denu, J.M.; Bäckhed, F.; Lusis, A.J.; et al. Interactions between Roseburia Intestinalis and Diet Modulate Atherogenesis in a Murine Model. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomaeus, H.; Balogh, A.; Yakoub, M.; Homann, S.; Markó, L.; Höges, S.; Tsvetkov, D.; Krannich, A.; Wundersitz, S.; Avery, E.G.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Propionate Protects From Hypertensive Cardiovascular Damage. Circulation 2019, 139, 1407–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortelote, G.G. Therapeutic Strategies for Hypertension: Exploring the Role of Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Kidney Physiology and Development. Pediatr. Nephrol 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Vera, I.; Toral, M.; De La Visitación, N.; Aguilera-Sánchez, N.; Redondo, J.M.; Duarte, J. Protective Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by Angiotensin II. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Moore, B.N.; Pluznick, J.L. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Receptors and Blood Pressure Regulation: Council on Hypertension Mid-Career Award for Research Excellence 2021. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2127–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, A.; Banpouri, S.; Ziaei, R.; Talebi, S.; Vajdi, M.; Nattagh-Eshtivani, E.; Barghchi, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Askari, G. Effect of Soluble Fiber on Blood Pressure in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsten, S.G.P.J.; Vromans, H.; Garssen, J.; Willemsen, L.E.M. Butyrate Protects Barrier Integrity and Suppresses Immune Activation in a Caco-2/PBMC Co-Culture Model While HDAC Inhibition Mimics Butyrate in Restoring Cytokine-Induced Barrier Disruption. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, E.C.; Leonel, A.J.; Teixeira, L.G.; Silva, A.R.; Silva, J.F.; Pelaez, J.M.N.; Capettini, L.S.A.; Lemos, V.S.; Santos, R.A.S.; Alvarez-Leite, J.I. Butyrate Impairs Atherogenesis by Reducing Plaque Inflammation and Vulnerability and Decreasing NFκB Activation. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffelner, D.K.; Hendrikx, T. Emerging Therapy Targets to Modulate Microbiome-Mediated Effects Evident in Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1631841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, N.T.; Zhang, M.; Juraschek, S.P.; Miller, E.R.; Appel, L.J. Effects of High-Fiber Diets Enriched with Carbohydrate, Protein, or Unsaturated Fat on Circulating Short Chain Fatty Acids: Results from the OmniHeart Randomized Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakaroun, R.M.; Olsson, L.M.; Bäckhed, F. The Potential of Tailoring the Gut Microbiome to Prevent and Treat Cardiometabolic Disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiattarella, G.G.; Sannino, A.; Toscano, E.; Giugliano, G.; Gargiulo, G.; Franzone, A.; Trimarco, B.; Esposito, G.; Perrino, C. Gut Microbe-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide as Cardiovascular Risk Biomarker: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2948–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.C.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Zhu, W.; Wagner, M.A.; Bennett, B.J.; Li, L.; DiDonato, J.A.; et al. Transmission of Atherosclerosis Susceptibility with Gut Microbial Transplantation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 5647–5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; Buffa, J.A.; Org, E.; Sheehy, B.T.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota Metabolism of L-Carnitine, a Nutrient in Red Meat, Promotes Atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Vajdi, M. Novel Findings of the Association between Gut Microbiota–Derived Metabolite Trimethylamine N- Oxide and Inflammation: Results from a Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2801–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Roberts, A.B.; Buffa, J.A.; Levison, B.S.; Zhu, W.; Org, E.; Gu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zamanian-Daryoush, M.; Culley, M.K.; et al. Non-Lethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine Production for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Cell 2015, 163, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, A.B.; Gu, X.; Buffa, J.A.; Hurd, A.G.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Gupta, N.; Skye, S.M.; Cody, D.B.; Levison, B.S.; et al. Development of a Gut Microbe–Targeted Nonlethal Therapeutic to Inhibit Thrombosis Potential. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Eckardstein, A.; Binder, C.J. (Eds.) Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis: Improving State-of-the-Art Management and Search for Novel Targets. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 270. [Google Scholar]

- Charach, G.; Argov, O.; Geiger, K.; Charach, L.; Rogowski, O.; Grosskopf, I. Diminished Bile Acids Excretion Is a Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease: 20-Year Follow up and Long-Term Outcome. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1756283X17743420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveter, K.M.; Mezhibovsky, E.; Wu, Y.; Roopchand, D.E. Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling: Emerging Pharmacological Targets of Dietary Polyphenols. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 248, 108457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukkanen, J.; Küblbeck, J.; Hakkola, J.; Rysä, J. Nuclear Receptors CAR and PXR as Cardiometabolic Regulators. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 219, 107892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriaa, A.; Bourgin, M.; Potiron, A.; Mkaouar, H.; Jablaoui, A.; Gérard, P.; Maguin, E.; Rhimi, M. Microbial Impact on Cholesterol and Bile Acid Metabolism: Current Status and Future Prospects. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juste, C.; Gérard, P. Cholesterol-to-Coprostanol Conversion by the Gut Microbiota: What We Know, Suspect, and Ignore. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.J.; Plichta, D.R.; Shungin, D.; Koppel, N.; Hall, A.B.; Fu, B.; Vasan, R.S.; Shaw, S.Y.; Vlamakis, H.; Balskus, E.P.; et al. Cholesterol Metabolism by Uncultured Human Gut Bacteria Influences Host Cholesterol Level. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 245–257.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Yu, B.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Qin, W.; Zhou, Z.; Su, M.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. SUCNR 1 Promotes Atherosclerosis by Inducing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Mediated ER-Mito Crosstalk. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Ma, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Gao, C. Succinate Metabolism and Its Regulation of Host-Microbe Interactions. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2190300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, A.; Mannerås-Holm, L.; Yunn, N.-O.; Nilsson, P.M.; Ryu, S.H.; Molinaro, A.; Perkins, R.; Smith, J.G.; Bäckhed, F. Microbial Imidazole Propionate Affects Responses to Metformin through P38γ-Dependent Inhibitory AMPK Phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 643–653.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.-K.; Kwon, B. Immune Regulation through Tryptophan Metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.K.; Vyavahare, S.; Duchesne Blanes, I.L.; Berger, F.; Isales, C.; Fulzele, S. Microbiota-Derived Tryptophan Metabolism: Impacts on Health, Aging, and Disease. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 183, 112319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chajadine, M.; Laurans, L.; Radecke, T.; Mouttoulingam, N.; Al-Rifai, R.; Bacquer, E.; Delaroque, C.; Rytter, H.; Bredon, M.; Knosp, C.; et al. Harnessing Intestinal Tryptophan Catabolism to Relieve Atherosclerosis in Mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, K.; Yang, Y.; Ling, W. Gut Microbially Produced Indole-3-Propionic Acid Inhibits Atherosclerosis by Promoting Reverse Cholesterol Transport and Its Deficiency Is Causally Related to Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Xia, H.; Zhong, S.-L.; Feng, Q.; Li, S.; Liang, S.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, H.; et al. The Gut Microbiome in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, O.; Spor, A.; Felin, J.; Fåk, F.; Stombaugh, J.; Tremaroli, V.; Behre, C.J.; Knight, R.; Fagerberg, B.; Ley, R.E.; et al. Human Oral, Gut, and Plaque Microbiota in Patients with Atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4592–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayols-Baixeras, S.; Dekkers, K.F.; Baldanzi, G.; Jönsson, D.; Hammar, U.; Lin, Y.-T.; Ahmad, S.; Nguyen, D.; Varotsis, G.; Pita, S.; et al. Streptococcus Species Abundance in the Gut Is Linked to Subclinical Coronary Atherosclerosis in 8973 Participants From the SCAPIS Cohort. Circulation 2023, 148, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-L.; Chen, B.-Y.; Feng, Z.-H.; Zhou, L.-J.; Liu, T.; Lin, W.-Z.; Zhu, H.; Xu, S.; Bai, X.-B.; Meng, X.-Q.; et al. Roles of Oral and Gut Microbiota in Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 74, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, Q.; Guan, P.; Qi, W.; Li, J.; Xi, M.; Xiao, L.; Zhong, S.; Ma, D.; Ni, J. Porphyromonas Gingivalis Regulates Atherosclerosis through an Immune Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1103592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Qin, Z.; Ling, Z.; Ge, X.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.; Liu, L.; Zheng, K.; Jiang, H.; Xu, R. Oral Pathogen Aggravates Atherosclerosis by Inducing Smooth Muscle Cell Apoptosis and Repressing Macrophage Efferocytosis. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzoon, S.; Amiri, M.A.; Mohebbi, M.; Hamedani, S.; Farshidfar, N. A Systematic Review of the Impact of Porphyromonas Gingivalis on Foam Cell Formation: Implications for the Role of Periodontitis in Atherosclerosis. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kurita-Ochiai, T.; Hashizume, T.; Du, Y.; Oguchi, S.; Yamamoto, M. Aggregatibacter Actinomycetemcomitans Accelerates Atherosclerosis with an Increase in Atherogenic Factors in Spontaneously Hyperlipidemic Mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.S.; Valdes, A.M. Evidence for Clinical Interventions Targeting the Gut Microbiome in Cardiometabolic Disease. BMJ 2023, 383, e075180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Chen, M.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Xie, X.; et al. Therapeutic Applications of Gut Microbes in Cardiometabolic Diseases: Current State and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, S.J. The Association between Dietary Fibre Deficiency and High-Income Lifestyle-Associated Diseases: Burkitt’s Hypothesis Revisited. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, D.P. Related Disease—Related Cause? Lancet 1969, 294, 1229–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkitt, D. Relationship as a Clue to Causation. Lancet 1970, 296, 1237–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Q.; Shen, L.; Guo, X.; Zhai, C.; Hu, H. Targeting Trimethylamine N-Oxide: A New Therapeutic Strategy for Alleviating Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 864600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.N.; Akerman, A.P.; Mann, J. Dietary Fibre and Whole Grains in Diabetes Management: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.M.; Kabisch, S.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Weickert, M.O. The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.-H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.-M.; Wang, W.-X.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, Y.-P.; Yue, S.-J. Intestinal Permeability in Human Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1361126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, C.D.; Gleeson, M.; Sulaiman, I. The Role of the Respiratory Microbiome in Asthma. Front. Allergy 2023, 4, 1120999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Molina, J.; García-Marcos, L. Microbiome and Asthma: Microbial Dysbiosis and the Origins, Phenotypes, Persistence, and Severity of Asthma. Nutrients 2023, 15, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roduit, C.; Frei, R.; Ferstl, R.; Loeliger, S.; Westermann, P.; Rhyner, C.; Schiavi, E.; Barcik, W.; Rodriguez-Perez, N.; Wawrzyniak, M.; et al. High Levels of Butyrate and Propionate in Early Life Are Associated with Protection against Atopy. Allergy 2019, 74, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, S.; Bertin, L.; Bonazzi, E.; Lorenzon, G.; De Barba, C.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Maniero, D.; Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Cammisotto, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Pignatelli, P.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C. Gut-Derived Low-Grade Endotoxaemia, Atherothrombosis and Cardiovascular Disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, B.; Khatibiyan Feyzabadi, Z.; Nouri, A.; Azadfallah, A.; Mahdizade Ari, M.; Hemmati, M.; Darban, M.; Alavi Toosi, P.; Banihashemian, S.Z. Atherosclerosis and Toll-Like Receptor4 (TLR4), Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein-1 (LOX-1), and Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type9 (PCSK9). Mediat. Inflamm. 2024, 2024, 5830491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Luo, K.; Dong, T. Association between Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Prognosis of Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1334730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losol, P.; Wolska, M.; Wypych, T.P.; Yao, L.; O’Mahony, L.; Sokolowska, M. A Cross Talk between Microbial Metabolites and Host Immunity: Its Relevance for Allergic Diseases. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2024, 14, e12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dhalla, N.S. The Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Ley, K. Immunity and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kral, M.; Van Der Vorst, E.P.C.; Surnov, A.; Weber, C.; Döring, Y. ILC2-Mediated Immune Crosstalk in Chronic (Vascular) Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1326440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Ingram, J.L.; Que, L.G. Effects of Oxidative Stress on Airway Epithelium Permeability in Asthma and Potential Implications for Patients with Comorbid Obesity. J. Asthma Allergy 2023, 16, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Beveren, G.J.; Said, H.; Van Houten, M.A.; Bogaert, D. The Respiratory Microbiome in Childhood Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 152, 1352–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razeghian-Jahromi, I.; Elyaspour, Z.; Zibaeenezhad, M.J.; Hassanipour, S. Prevalence of Microorganisms in Atherosclerotic Plaques of Coronary Arteries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 8678967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-saadawi, A.A.; Hafez, M.R.; Ibrahim, R.S.; Eid, H.A.; Sakr, L.K. Study of Atherosclerosis in Bronchial Asthma Patients. J. Recent Adv. Med. 2024, 5, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegati, L.M.; De Oliveira, E.E.; Oliveira, B.D.C.; Macedo, G.C.; De Castro E Silva, F.M. Asthma, Obesity, and Microbiota: A Complex Immunological Interaction. Immunol. Lett. 2023, 255, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Luo, S.; Wang, M.; Huang, Q.; Deng, Z.; De Febbo, C.; Daoui, A.; Liew, P.X.; Sukhova, G.K.; et al. IgE Contributes to Atherosclerosis and Obesity by Affecting Macrophage Polarization, Macrophage Protein Network, and Foam Cell Formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbru, E.-L.; Zimbru, R.-I.; Ordodi, V.-L.; Bojin, F.-M.; Crîsnic, D.; Andor, M.; Mirica, S.-N.; Huțu, I.; Tănasie, G.; Haidar, L.; et al. Rosuvastatin Attenuates Vascular Dysfunction Induced by High-Fructose Diets and Allergic Asthma in Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; He, S.; Song, Z.; Chen, S.; Lin, X.; Sun, H.; Zhou, P.; Peng, Q.; Du, S.; Zheng, S.; et al. Macrophage Polarization States in Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1185587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, L.; Bănărescu, C.F.; Uța, C.; Zimbru, E.-L.; Zimbru, R.-I.; Tîrziu, A.; Pătrașcu, R.; Șerb, A.-F.; Georgescu, M.; Nistor, D.; et al. Beyond the Skin: Exploring the Gut–Skin Axis in Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria and Other Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldriwesh, M.G.; Al-Mutairi, A.M.; Alharbi, A.S.; Aljohani, H.Y.; Alzahrani, N.A.; Ajina, R.; Alanazi, A.M. Paediatric Asthma and the Microbiome: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; He, Y.; Dang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lu, W. Gut Microbiota-Derived Tryptophan Metabolites Alleviate Allergic Asthma Inflammation in Ovalbumin-Induced Mice. Foods 2024, 13, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, N.; Mahmoudi, M.; Halperin, F.; Wu, J.C.; Pakpour, S. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Opportunities and Challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]