Neuron–Glioma Synapses in Tumor Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Evolution of the Glioma Concept

3. Glioma Biology and Tumor Microenvironment Characteristics

4. Structural and Functional Evidence for Neuron–Glioma Synapses

5. Molecular Mechanisms of Synaptic Communication

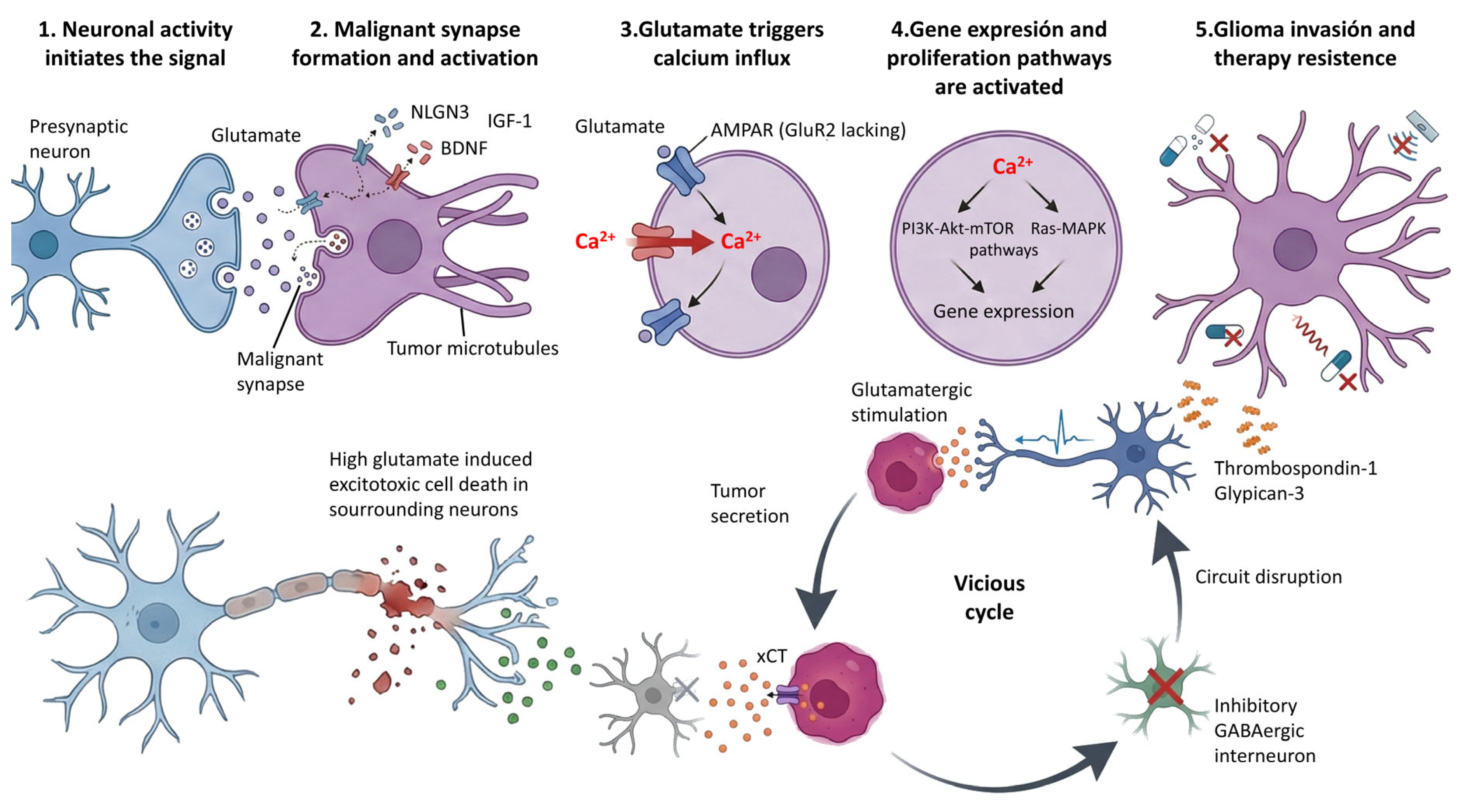

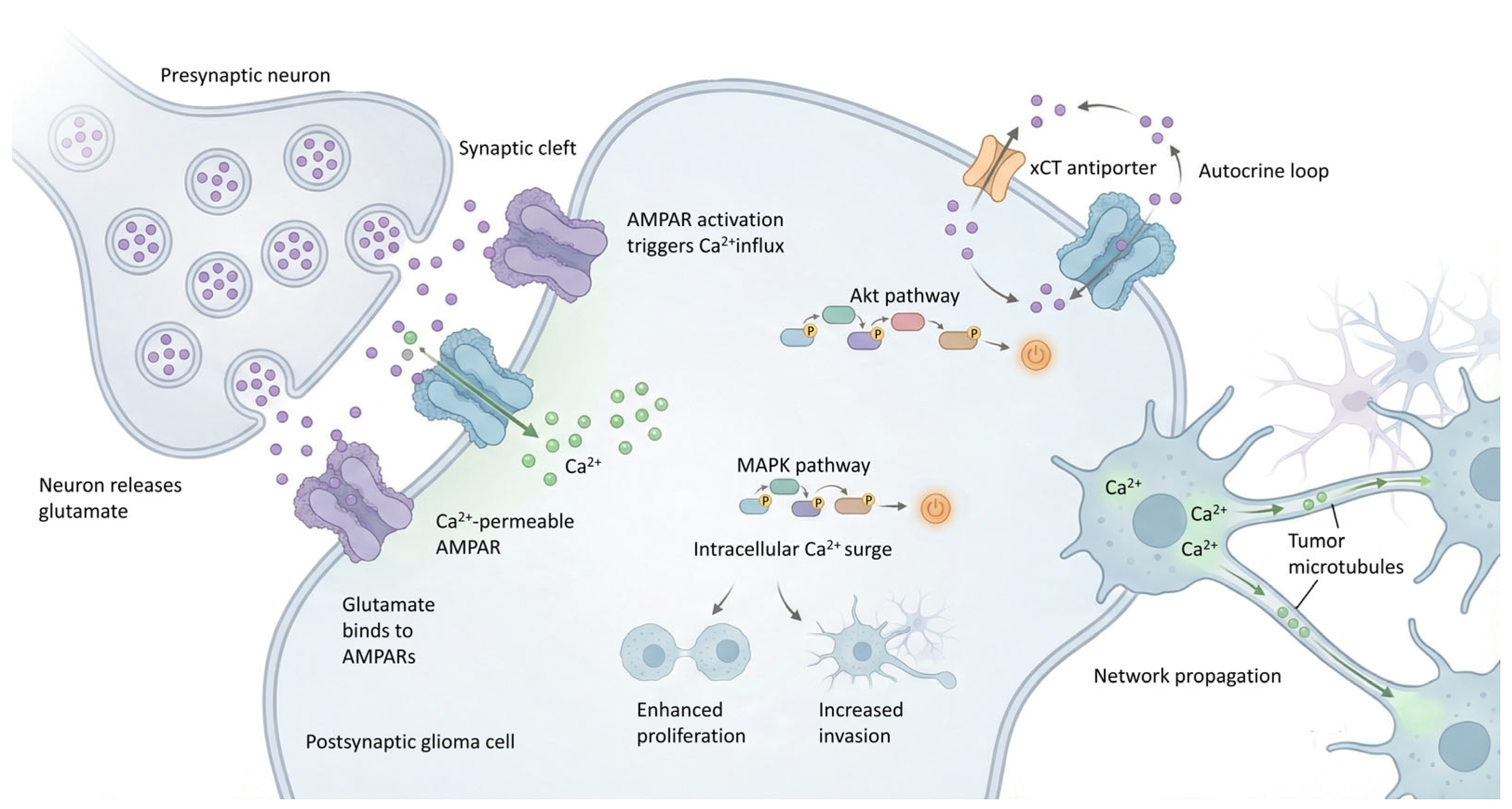

5.1. Glutamatergic Neurotransmission

| Mechanism/ Pathway | Description | Effect on Glioma or Microenvironment | Key Molecules, Receptors or Transporters | Pathological Outcome Relevant Glioma Type | Therapeutic Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamatergic synapse [4,63,71,72,73] | Neurons release glutamate at the neuron–glioma synapse, activating AMPA and NMDA receptors on tumor cells. Promotes depolarization and Ca2+ influx, triggering oncogenic signaling (MAPK, Akt, PI3K/Akt/mTOR). | EPSCs in glioma cells. AMPAR activation drives TMs formation and dynamics. Overall, promotes proliferation, invasion, and increased malignant plasticity. | AMPARs, often Ca2+ permeable due to lack of GluR2; NMDARs; TMs. | High-grade gliomas. Proliferation, invasion, TMs formation, increased malignant plasticity. | Perampanel AMPA antagonist. Disruption of TMsMemantine NMDA antagonist. |

| Autocrine or paracrine glutamate release [4,63,71,72,73] | Glioma cells secrete large amounts of glutamate into the extracellular space in an autocrine/paracrine manner. | Extracellular glutamate levels increased ~100-fold. Induces excitotoxicity in surrounding inhibitory GABAergic interneurons, shifting the excitatory-inhibitory balance, promoting neuronal hyperexcitability and glioma progression and invasion. | Cystine-glutamate antiporter xCT (SLC7A11 system). | General glioma/GBM. Promotes tumor growth, neuronal hyperexcitability, excitotoxicity, and therapeutic failure. | Sulfasalazine (xCT inhibitor). Riluzole/troriluzole (modulators of glutamate release). |

| GABAergic excitation [4,13,29,30,79] | Activation of GABAA receptors in tumor cells results in depolarization instead of inhibition due to high intracellular Cl−. | GABA-mediated depolarization caused by reversal of the chloride gradient. Promotes proliferation and tumor growth in DMGs, contributing to network hyperexcitability. | GABAARs; Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1 (overexpressed); KCC2 (reduced). | DMGs. Proliferation and hyperexcitability. | Bumetanide (NKCC1 inhibitor). GABA receptor inhibitors (e.g., flumazenil). |

| Synaptogenic paracrine factors [13,29,30,71,72,73,79] | Tumor and/or neuronal cells release synaptogenic factors that enhance neuron–glioma synaptogenesis and plasticity. | Neuroligin-3 (NLGN3) activates PI3K-mTOR signaling and promotes proliferation. BDNF enhances AMPAR trafficking and synaptic plasticity. TSP-1 and SPARCL1 promote synapse formation, increasing synaptogenesis, malignant plasticity, and tumor invasion. | Neuroligin-3 (NLGN3); BDNF/TrkB; Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1); SPARCL1; α2δ-1 subunit. | Proliferation, synaptogenesis, malignant plasticity, increased tumor invasion. | TrkB inhibitors (genetic/pharmacological). Gabapentin/Pregabalin (α2δ-1 binders). |

| Structural connectivity/Tumor network [29,30,63,71,72,73,79] | Glioma cells form multicellular networks via tumor microtubules and gap junctions, enabling structural and functional connectivity. | Propagation of Ca2+ waves across the tumor network, distribution of organelles and toxic metabolites among connected cells. Facilitates coordinated growth, invasion, and resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy. | TMs; Connexin 43 (Cx43) Gap Junctions. | Therapeutic resistance (chemo/radio), invasion, coordinated growth, increased malignant plasticity. | Gap junction inhibitors (e.g., meclofenamate). Agents disrupting TMs (e.g., Perampanel). |

| Cholinergic signaling [13,29,30,71,72,73,79] | Cholinergic neurons signal to DMG cells primarily through muscarinic receptors M1 and M3. DMG cells in turn enhance cholinergic circuit activity. | Cholinergic neuronal activity promotes DMG proliferation, Ca2+ transients, migration, and circuit-dependent growth. DMGs reciprocally increase cholinergic activity, creating a feed-forward loop between tumor and neuronal network. | Muscarinic receptors M1 (CHRM1) and M3 (CHRM3). | DMGs. Promotes proliferation, migration, and circuit-dependent growth. | M1/M3 receptor antagonists (e.g., VU0255035, 4-DAMP). |

| Dopaminergic signaling [4,29,30,71,72,73,79] | Dopamine signaling via DRD2 in GBM cells activates oncogenic pathways and modulates susceptibility to apoptosis-inducing ligands. | DRD2 activates MET signaling, supporting GBM stemness and clonogenic growth. DRD2 inhibition promotes interaction of MET with TRAIL receptors (DR4/5), sensitizing cells to apoptosis and reducing stem-like properties. | Dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2); MET receptor; TRAIL receptors DR4/5. | Promotes GBM stemness and clonogenic growth via DRD2-MET axis. DRD2 antagonists can induce apoptosis and reduce stem-like features. | DRD2 antagonists (e.g., Perphenazine, ONC201, ONC206). |

| Acid sensing [4,13,80] | Acidic tumor microenvironment activates neuronal ASIC1a channels, modulating neuronal activity and neurotransmitter release that impact glioma behavior. | Neuronal activation and neurotransmitter release induced by acidic TME support tumor growth. Genetic deletion or pharmacologic inhibition of neuronal ASIC1a reduces tumor size and prolongs survival in preclinical models. | Neuronal acid-sensing ion channel 1a (ASIC1a). | Tumor growth supported by acid-sensing-driven neuronal activity. Deletion or inhibition of ASIC1a reduces tumor burden and prolongs survival. | Pharmacological inhibition of neuronal ASIC1a. |

Modulation of Glutamate Metabolism

5.2. GABAergic Neurotransmission

5.3. Other Neurotransmitter and Neuromodulatory Systems

5.4. Secreted Factors and Paracrine Signaling

5.5. Ion Channels and Membrane Potential Regulation

6. Epigenetic and Transcriptional Regulation

7. Mechanisms of Facilitation of Tumor Invasion

7.1. Neuronal-like Phenotype and Non-Connected Cells

7.2. The Central Role of Tumor Microtubules (TMs)

7.3. Induction of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs)

7.4. Axonal Projections as Migration Pathways

7.5. Modification of Biomechanical Properties

8. Resistance to Therapies

9. Open Questions and Controversies in Neuron–Glioma Synapse Research

9.1. Context-Dependent Signaling and Tumor Heterogeneity

9.2. Unresolved Synaptic Characteristics

9.3. Methodological Limitations and Translational Challenges

9.4. Barriers of Therapeutic Translation

9.4.1. Limitations of Clinical Efficacy and Trial Design

9.4.2. Specificity Concerns and Adverse Effects

9.4.3. Impact of Tumor Heterogeneity

10. Impact on Survival

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPA | α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid receptor |

| AMPAR | AMPA receptor |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| ASIC1a | Acid-sensing ion channel 1a |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CaMKII | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| Cx43 | Connexin 43 |

| DMG | Diffuse midline glioma |

| ECoG | Electrocorticography |

| EGABA | GABA reversal potential |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EPSC | Excitatory postsynaptic current |

| Erk | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| GAP43 | Growth-associated protein 43 |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GABAAR | GABA type A receptor |

| GCaMP6s | Genetically encoded calcium indicator (variant 6s) |

| GluR2 | Glutamate receptor subunit 2 (GluA2) |

| HDI-WT | Hemispheric high-grade glioma, IDH-wildtype |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IGF-1R | Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor |

| IP3 | Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate |

| KCC2 | K+-Cl− cotransporter 2 |

| LTP | Long-term potentiation |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| mGlu3 | Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | mTOR complex 1 |

| NKCC1 | Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter 1 |

| NLGN3 | Neuroligin-3 |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate (receptor) |

| OPC | Oligodendrocyte precursor cell |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PSD95 | Postsynaptic density protein 95 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| SCLC | Small cell lung carcinoma |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 member 11 (xCT) |

| SRC | SRC proto-oncogene tyrosine kinase |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TM | Tumor microtube |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin receptor kinase B (NTRK2) |

| TSP-1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| VGLUT | Vesicular glutamate transporter |

| xCT | Cystine/glutamate antiporter (SLC7A11) |

References

- Aabedi, A.A.; Lipkin, B.; Kaur, J.; Kakaizada, S.; Valdivia, C.; Reihl, S.; Young, J.S.; Lee, A.T.; Krishna, S.; Berger, M.S.; et al. Functional alterations in cortical processing of speech in glioma-infiltrated cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2108959118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, T.; Shi, H.; Zhu, M.; Chen, C.; Su, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, Q.; Wang, H. Glioma-neuronal interactions in tumor progression: Mechanism, therapeutic strategies and perspectives (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2022, 61, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picart, T.; Hervey-Jumper, S. Central nervous system regulation of diffuse glioma growth and invasion: From single unit physiology to circuit remodeling. J. Neurooncol 2024, 169, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, M.; Baiardi, G.; Pasquariello, S.; Sacco, F.; Dellacasagrande, I.; Corsaro, A.; Mattioli, F.; Barbieri, F. Antitumor Potential of Antiepileptic Drugs in Human Glioblastoma: Pharmacological Targets and Clinical Benefits. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Schubert, M.C.; Kuner, T.; Wick, W.; Winkler, F.; Venkataramani, V. Brain Tumor Networks in Diffuse Glioma. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Jin, Z.; Ge, Q.; Pan, Y.; Du, J. Neuronal acid-sensing ion channel 1a regulates neuron-to-glioma synapses. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang-Hobbs, E.; Cheng, Y.T.; Ko, Y.; Luna-Figueroa, E.; Lozzi, B.; Taylor, K.R.; McDonald, M.; He, P.; Chen, H.C.; Yang, Y.; et al. Remote neuronal activity drives glioma progression through SEMA4F. Nature 2023, 619, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beichert, J.; Hoffmann, D.C.; Winkler, F.; Ratliff, M. Innovative Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the Network Architecture of Glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 2864–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, S.; Burghaus, I.; Gose, M.; Kessler, T.; Sahm, F.; Vollmuth, P.; Venkataramani, V.; Hoffmann, D.; Schlesner, M.; Ratliff, M.; et al. PerSurge (NOA-30) phase II trial of perampanel treatment around surgery in patients with progressive glioblastoma. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, L.H.; Bergstrom, C.K.; Laakkonen, P.M.; Le Joncour, V. Deciphering the Dialogue between Brain Tumors, Neurons, and Astrocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 2025, 195, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenge, A.; Castro-Vega, L.J.; Huberfeld, G. Reciprocal interactions between glioma and tissue-resident cells fueling tumor progression. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2025, 210, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamardani, K.; Taylor, K.R.; Barron, T.; Monje, M. Studying Synaptic Integration of Glioma Cells into Neural Circuits. In New Technologies for Glutamate Interaction;Neuromethods; Kukley, M., Ed.; Neuromethods; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 345–368. [Google Scholar]

- Drexler, R.; Drinnenberg, A.; Gavish, A.; Yalcin, B.; Shamardani, K.; Rogers, A.E.; Mancusi, R.; Trivedi, V.; Taylor, K.R.; Kim, Y.S.; et al. Cholinergic neuronal activity promotes diffuse midline glioma growth through muscarinic signaling. Cell 2025, 188, 4640–4657 e4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Mao, X.; Sun, H. Deciphering the CNS-glioma dialogue: Advanced insights into CNS-glioma communication pathways and their therapeutic potential. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2024, 16, 11795735241292188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstock, J.D.; Gerstl, J.V.E.; Chen, J.A.; Johnston, B.R.; Nonnenbroich, L.F.; Spanehl, L.; Gessler, F.A.; Valdes, P.A.; Lu, Y.; Srinivasan, S.S.; et al. The Case for Neurosurgical Intervention in Cancer Neuroscience. Neurosurgery 2025, 96, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Alfonso, J.; Monyer, H.; Wick, W.; Winkler, F. Neuronal signatures in cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 3281–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osswald, M.; Jung, E.; Sahm, F.; Solecki, G.; Venkataramani, V.; Blaes, J.; Weil, S.; Horstmann, H.; Wiestler, B.; Syed, M.; et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature 2015, 528, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelat, R.; Jihua, N.; Sanchez Trivino, C.A.; Pifferi, S.; Pozzi, D.; Manzati, M.; Mortal, S.; Schiavo, I.; Spada, F.; Zanchetta, M.E.; et al. The dual action of glioma-derived exosomes on neuronal activity: Synchronization and disruption of synchrony. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, T.; Yalcin, B.; Su, M.; Byun, Y.G.; Gavish, A.; Shamardani, K.; Xu, H.; Ni, L.; Soni, N.; Mehta, V.; et al. GABAergic neuron-to-glioma synapses in diffuse midline gliomas. Nature 2025, 639, 1060–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Nissen, I.; Vincent, C.A.; Hagglund, A.C.; Hornblad, A.; Remeseiro, S. Rewiring of the promoter-enhancer interactome and regulatory landscape in glioblastoma orchestrates gene expression underlying neurogliomal synaptic communication. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, S.; Winkler, F. Glioblastoma revisited: From neuronal-like invasion to pacemaking. Trends Cancer 2023, 9, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, S.; Choudhury, A.; Keough, M.B.; Seo, K.; Ni, L.; Kakaizada, S.; Lee, A.; Aabedi, A.; Popova, G.; Lipkin, B.; et al. Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature 2023, 617, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, E.; Cheng, J.; Ma, Y.; Yang, T.; Wu, J.; Sun, H.; et al. Glioma-derived SPARCL1 promotes the formation of peritumoral neuron-glioma synapses. J. Neurooncol. 2025, 173, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada-Perez, M.; Hernandez Garcia-Moreno, M.; Garcia-Ricote, I.; Casas-Tinto, S. Synaptic components are required for glioblastoma progression in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastall, M.; Roth, P.; Bink, A.; Fischer Maranta, A.; Laubli, H.; Hottinger, A.F.; Hundsberger, T.; Migliorini, D.; Ochsenbein, A.; Seystahl, K.; et al. A phase Ib/II randomized, open-label drug repurposing trial of glutamate signaling inhibitors in combination with chemoradiotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: The GLUGLIO trial protocol. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, J.; Huse, J.T. Neurotransmitter power plays: The synaptic communication nexus shaping brain cancer. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Hysinger, J.D.; Barron, T.; Schindler, N.F.; Cobb, O.; Guo, X.; Yalcin, B.; Anastasaki, C.; Mulinyawe, S.B.; Ponnuswami, A.; et al. NF1 mutation drives neuronal activity-dependent initiation of optic glioma. Nature 2021, 594, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchuk, S.; Gentry, K.; Wang, W.; Carleton, E.; Yalcin, B.; Liu, Y.; Pavarino, E.C.; LaBelle, J.; Toland, A.M.; Woo, P.J.; et al. Neuronal-Activity Dependent Mechanisms of Small Cell Lung Cancer Progression. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.R.; Barron, T.; Hui, A.; Spitzer, A.; Yalcin, B.; Ivec, A.E.; Geraghty, A.C.; Hartmann, G.G.; Arzt, M.; Gillespie, S.M.; et al. Glioma synapses recruit mechanisms of adaptive plasticity. Nature 2023, 623, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.R.; Monje, M. Neuron-oligodendroglial interactions in health and malignant disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobochnik, S.; Regan, M.S.; Dorotan, M.K.C.; Reich, D.; Lapinskas, E.; Hossain, M.A.; Stopka, S.; Meredith, D.M.; Santagata, S.; Murphy, M.M.; et al. Pilot Trial of Perampanel on Peritumoral Hyperexcitability in Newly Diagnosed High-grade Glioma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 5365–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Chen, M.B.; Cheng, K.W.; Qi, L.N.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Peng, Y.; Li, K.R.; Liu, F.; Chen, G.; et al. Neuronal-driven glioma growth requires Galphai1 and Galphai3. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8535–8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bhattarai, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Park, K.H.; Dong, W.; Hung, Y.F.; Yang, Q.; et al. Brain-wide neuronal circuit connectome of human glioblastoma. Nature 2025, 641, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beier, C.P.; Rasmussen, T.; Dahlrot, R.H.; Tenstad, H.B.; Aaro, J.S.; Sorensen, M.F.; Heimisdottir, S.B.; Sorensen, M.D.; Svenningsen, P.; Riemenschneider, M.J.; et al. Aberrant neuronal differentiation is common in glioma but is associated neither with epileptic seizures nor with better survival. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, A.L.; Ganesh, S.; Kula, T.; Irshad, M.; Ferenczi, E.A.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.C.; Hu, S.H.; Li, Z.; Joshi, S.; et al. Widespread neuroanatomical integration and distinct electrophysiological properties of glioma-innervating neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2417420121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, P.; Peng, X. Paracrine function amplifies pro-tumor electrochemical signal within neuron-glioma synapses. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 1318–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Monje, M. Neuron-Glial Interactions in Health and Brain Cancer. Adv. Biol. 2022, 6, e2200122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Menna, G.; Izzo, A.; D’Ercole, M.; Della Pepa, G.M.; Lauretti, L.; Pallini, R.; Olivi, A.; Montano, N. Neuromodulation for Brain Tumors: Myth or Reality? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wang, Y. Neural Influences on Tumor Progression Within the Central Nervous System. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e70097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleszewska, M.; Roura, A.J.; Dabrowski, M.J.; Draminski, M.; Wojtas, B. Decoding glioblastoma’s diversity: Are neurons part of the game? Cancer Lett. 2025, 620, 217666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvalaggio, A.; Pini, L.; Bertoldo, A.; Corbetta, M. Glioblastoma and brain connectivity: The need for a paradigm shift. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsching, H.G.; Weller, M. Does Neuronal Activity Promote Glioma Progression? Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, S.; Tao, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Shao, Y.; Yi, Y. Development and validation of a two glycolysis-related LncRNAs prognostic signature for glioma and in vitro analyses. Cell Div. 2023, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, S.; Monje, M. An active role for neurons in glioma progression: Making sense of Scherer’s structures. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radin, D.P.; Tsirka, S.E. Interactions between Tumor Cells, Neurons, and Microglia in the Glioma Microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Aaroe, A.; Liang, J.; Puduvalli, V.K. Tumor microenvironment in glioblastoma: Current and emerging concepts. Neurooncol Adv. 2023, 5, vdad009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varn, F.S.; Johnson, K.C.; Martinek, J.; Huse, J.T.; Nasrallah, M.P.; Wesseling, P.; Cooper, L.A.D.; Malta, T.M.; Wade, T.E.; Sabedot, T.S.; et al. Glioma progression is shaped by genetic evolution and microenvironment interactions. Cell 2022, 185, 2184–2199.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright-Jin, E.C.; Gutmann, D.H. Microglia as Dynamic Cellular Mediators of Brain Function. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Duan, S.; Apostolou, P.E.; Wu, X.; Watanabe, J.; Gallitto, M.; Barron, T.; Taylor, K.R.; Woo, P.J.; Hua, X.; et al. CHD2 Regulates Neuron-Glioma Interactions in Pediatric Glioma. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 1732–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, T.H.; Liu, J.; Wen, Q.; Yang, X.Y.; Deng, Y.; Duan, J.J.; Yu, S.C. Structural and material basis of neuron-glioma interactions. Cancer Lett. 2025, 628, 217843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.R.; Weaver, A.M. Astrocyte-derived small extracellular vesicles promote synapse formation via fibulin-2-mediated TGF-beta signaling. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbin, M.G.; Sturm, D. Gliomas in Children. Semin. Neurol. 2018, 38, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, R.; Wang, Q.; Schupp, P.G.; Nikolic, A.; Hilz, S.; Hong, C.; Grishanina, N.R.; Kwok, D.; Stevers, N.O.; Jin, Q.; et al. Glioblastoma evolution and heterogeneity from a 3D whole-tumor perspective. Cell 2024, 187, 446–463 e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neftel, C.; Laffy, J.; Filbin, M.G.; Hara, T.; Shore, M.E.; Rahme, G.J.; Richman, A.R.; Silverbush, D.; Shaw, M.L.; Hebert, C.M.; et al. An Integrative Model of Cellular States, Plasticity, and Genetics for Glioblastoma. Cell 2019, 178, 835–849.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolma, S.; Selvadurai, H.J.; Lan, X.; Lee, L.; Kushida, M.; Voisin, V.; Whetstone, H.; So, M.; Aviv, T.; Park, N.; et al. Inhibition of Dopamine Receptor D4 Impedes Autophagic Flux, Proliferation, and Survival of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, H.S. The neural regulation of cancer. Science 2019, 366, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimaschewski, L.; Claus, P. Fibroblast Growth Factor Signalling in the Diseased Nervous System. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 3884–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazi, M.; Muller, P.; Pitsch, J.; van Loo, K.M.J.; Quatraccioni, A.; Opitz, T.; Schoch, S.; Becker, A.J.; Cases-Cunillera, S. Neurochemical Profile of BRAFV600E/AktT308D/S473D Mouse Gangliogliomas Reveals Impaired GABAergic System Inhibition. Dev. Neurosci. 2023, 45, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantillo, E.; Vannini, E.; Cerri, C.; Spalletti, C.; Colistra, A.; Mazzanti, C.M.; Costa, M.; Caleo, M. Differential roles of pyramidal and fast-spiking, GABAergic neurons in the control of glioma cell proliferation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 141, 104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, E.; Funahashi, Y.; Faruk, M.O.; Ahammad, R.U.; Amano, M.; Yamada, K.; Kaibuchi, K. Rho-Kinase/ROCK Phosphorylates PSD-93 Downstream of NMDARs to Orchestrate Synaptic Plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, A.M.; Rosenfeld, S.S.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A. Altered glutamatergic and inflammatory pathways promote glioblastoma growth, invasion, and seizures: An overview. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 443, 120488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethe, E.A.; Deneen, B.; Noebels, J.; Rao, G. The Role of Hyperexcitability in Gliomagenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, F.; Wesslau, K.; Porath, K.; Hornschemeyer, M.F.; Bergner, C.; Krause, B.J.; Mullins, C.S.; Linnebacher, M.; Kohling, R.; Kirschstein, T. AMPA receptor antagonist perampanel affects glioblastoma cell growth and glutamate release in vitro. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobochnik, S.; Regan, M.S.; Dorotan, M.K.C.; Reich, D.; Lapinskas, E.; Hossain, M.A.; Stopka, S.; Santagata, S.; Murphy, M.M.; Arnaout, O.; et al. Pilot trial of perampanel on peritumoral hyperexcitability and clinical outcomes in newly diagnosed high-grade glioma. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hino, U.; Tamura, R.; Kosugi, K.; Ezaki, T.; Karatsu, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Tomioka, A.; Toda, M. Optimizing perampanel monotherapy for surgically resected brain tumors. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, H.B.; Wojkowski, J. Antiepileptic Strategies for Patients with Primary and Metastatic Brain Tumors. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2024, 25, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, J.; Cavallieri, F.; Bassi, M.C.; Biagini, G.; Rizzi, R.; Russo, M.; Bondavalli, M.; Iaccarino, C.; Pavesi, G.; Cozzi, S.; et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of Perampanel in Brain Tumor-Related Epilepsy: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffel, T.B.; Diz, F.M.; Wieck, A.; Begnini, K.R.; da Costa, J.C. The molecular landscape of glioblastoma-associated epilepsy. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 103, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabaee Damavandi, P.; Pasini, F.; Fanella, G.; Cereda, G.S.; Mainini, G.; DiFrancesco, J.C.; Trinka, E.; Lattanzi, S. Perampanel in Brain Tumor-Related Epilepsy: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Yu, Q.; Wu, H. The efficacy and safety of novel antiepileptic drugs in treatment of epilepsy of patients with brain tumors. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1344775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramani, V.; Tanev, D.I.; Kuner, T.; Wick, W.; Winkler, F. Synaptic input to brain tumors: Clinical implications. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramani, V.; Tanev, D.I.; Strahle, C.; Studier-Fischer, A.; Fankhauser, L.; Kessler, T.; Korber, C.; Kardorff, M.; Ratliff, M.; Xie, R.; et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature 2019, 573, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramani, V.; Yang, Y.; Schubert, M.C.; Reyhan, E.; Tetzlaff, S.K.; Wissmann, N.; Botz, M.; Soyka, S.J.; Beretta, C.A.; Pramatarov, R.L.; et al. Glioblastoma hijacks neuronal mechanisms for brain invasion. Cell 2022, 185, 2899–2917.e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, H.S.; Morishita, W.; Geraghty, A.C.; Silverbush, D.; Gillespie, S.M.; Arzt, M.; Tam, L.T.; Espenel, C.; Ponnuswami, A.; Ni, L.; et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature 2019, 573, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altas, B.; Tuffy, L.P.; Patrizi, A.; Dimova, K.; Soykan, T.; Brandenburg, C.; Romanowski, A.J.; Whitten, J.R.; Robertson, C.D.; Khim, S.N.; et al. Region-Specific Phosphorylation Determines Neuroligin-3 Localization to Excitatory Versus Inhibitory Synapses. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 96, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemben, M.A.; Nguyen, T.A.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Nicoll, R.A.; Roche, K.W. Isoform-specific cleavage of neuroligin-3 reduces synapse strength. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, D.P. AMPA Receptor Modulation in the Treatment of High-Grade Glioma: Translating Good Science into Better Outcomes. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, H.; Cui, Q. A Panel of Synapse-Related Genes as a Biomarker for Gliomas. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.R.; Monje, M. Invasive glioma cells: The malignant pioneers that follow the current. Cell 2022, 185, 2846–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemmie, J.A.; Taugher, R.J.; Kreple, C.J. Acid-sensing ion channels in pain and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastall, M.; Wolpert, F.; Gramatzki, D.; Imbach, L.; Becker, D.; Schmick, A.; Hertler, C.; Roth, P.; Weller, M.; Wirsching, H.G. Survival of brain tumour patients with epilepsy. Brain 2021, 144, 3322–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, D.; Lee, Y.; Tsuchiya, M.; Tahira, T.; Mizutani, H.; Ohara, N. Docosahexaenoic Acid Increases Vesicular Glutamate Transporter 2 Protein Levels in Differentiated NG108-15 Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 45, 1385–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sanchez, M.; Ramirez-Exposito, M.J.; Martinez-Martos, J.M. Pathophysiology, Clinical Heterogeneity, and Therapeutic Advances in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular Mechanisms, Diagnostic Challenges, and Multidisciplinary Management Strategies. Life 2025, 15, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzaki, M. Two Classes of Secreted Synaptic Organizers in the Central Nervous System. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2018, 80, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, S.L.; Robel, S.; Cuddapah, V.A.; Robert, S.; Buckingham, S.C.; Kahle, K.T.; Sontheimer, H. GABAergic disinhibition and impaired KCC2 cotransporter activity underlie tumor-associated epilepsy. Glia 2015, 63, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.M.; Oh, Y.T.; Shin, Y.J.; Chang, N.; Kim, D.; Woo, D.; Yeup, Y.; Joo, K.M.; Jo, H.; Yang, H.; et al. Dopamine receptor D2 regulates glioblastoma survival and death through MET and death receptor 4/5. Neoplasia 2023, 39, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudin, P.; Cousyn, L.; Navarro, V. The LGI1 protein: Molecular structure, physiological functions and disruption-related seizures. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 79, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremet, J.; El Far, O.; Ankri, N.; Irani, S.R.; Debanne, D.; Russier, M. An Epitope-Specific LGI1-Autoantibody Enhances Neuronal Excitability by Modulating Kv1.1 Channel. Cells 2022, 11, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fels, E.; Muniz-Castrillo, S.; Vogrig, A.; Joubert, B.; Honnorat, J.; Pascual, O. Role of LGI1 protein in synaptic transmission: From physiology to pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 160, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, N.S.; Choi, M.; Ko, S.Y.; Wang, S.E.; Jo, H.R.; Seo, J.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, H.Y.; et al. LGI1 governs neuritin-mediated resilience to chronic stress. Neurobiol. Stress. 2021, 15, 100373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugara, E.; Kaushik, R.; Leite, M.; Chabrol, E.; Dityatev, A.; Lignani, G.; Walker, M.C. LGI1 downregulation increases neuronal circuit excitability. Epilepsia 2020, 61, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit-Pedrol, M.; Sell, J.; Planaguma, J.; Mannara, F.; Radosevic, M.; Haselmann, H.; Ceanga, M.; Sabater, L.; Spatola, M.; Soto, D.; et al. LGI1 antibodies alter Kv1.1 and AMPA receptors changing synaptic excitability, plasticity and memory. Brain 2018, 141, 3144–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritzau-Jost, A.; Gsell, F.; Sell, J.; Sachs, S.; Montanaro, J.; Kirmann, T.; Maass, S.; Irani, S.R.; Werner, C.; Geis, C.; et al. LGI1 Autoantibodies Enhance Synaptic Transmission by Presynaptic K(v)1 Loss and Increased Action Potential Broadening. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 11, e200284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.A.; Gibon, J.; Chen, C.X.Q.; Chierzi, S.; Soubannier, V.G.; Baulac, S.; Seguela, P.; Murai, K.; Barker, P.A. The Nogo Receptor Ligand LGI1 Regulates Synapse Number and Synaptic Activity in Hippocampal and Cortical Neurons. eNeuro 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dazzo, E.; Pasini, E.; Furlan, S.; de Biase, D.; Martinoni, M.; Michelucci, R.; Nobile, C.; Group, P.S. LGI1 tumor tissue expression and serum autoantibodies in patients with primary malignant glioma. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 170, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.S.; Kim, H.; Han, K.S. Mechanisms of Invasion in Glioblastoma: Extracellular Matrix, Ca2+ Signaling, and Glutamate. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 663092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.E.; Echeandia Marrero, A.S.; Pan, Y. Disrupting neuron-tumor networking connections. Cell Chem. Biol. 2025, 32, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Qiu, W.; Wang, C.; Qi, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, S.; Zhao, R.; Cheng, B.; Han, X.; Du, H.; et al. Neuronal Activity Promotes Glioma Progression by Inducing Proneural-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Glioma Stem Cells. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horschitz, S.; Jabali, A.; Heuer, S.; Zillich, E.; Zillich, L.; Hoffmann, D.C.; Kumar, A.S.; Hausmann, D.; Azorin, D.D.; Hai, L.; et al. Development of a fully human glioblastoma-in-brain-spheroid model for accelerated translational research. J. Adv. Res. 2026, 79, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Source | Mechanism of Action/Receptor | Effect on Glioma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroligin-3 (NLGN3) [29,30,32,50,71,72,73,79] | Neurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). | Secreted in response to neuronal activity. Binds to receptors on tumor cells, activating oncogenic pathways (PI3K-mTOR, SRC, RAS). | Potent mitogen; promotes proliferation and growth. NLGN3 expression correlates inversely with overall survival. |

| Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [29,30,39,79] | Neurons. | Activates the BDNF/TrkB (NTRK2) pathway in glioma cells. Promotes AMPA receptor trafficking to the membrane. | Enhances proliferation, malignant synaptic plasticity, and increases the amplitude of glutamate-evoked currents. |

| Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) [5,22,29,30,79] | Glioblastoma cells. | Binds to the α2δ-1 receptor (VSCC component) on neurons. | Promotes the formation of new synapses, neuronal hyperexcitability, and TMs formation. |

| SPARCL1 (hevin) [23,26,29,30,79] | Glioma cells (especially astrocytic tumors). | Associated with synaptogenesis. Overexpression significantly increases neuron–glioma synapse formation on TMs. | Favors tumor growth and aberrant neuronal circuit formation. |

| Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) [27,29,30,37,39,79] | Specific neurons (e.g., olfactory bulb cells). | Released in response to sensory/neuronal activity. | Promotes tumor cell proliferation and gliomagenesis. |

| Target/Mechanism | Role in Glioma Interaction | Therapeutic Strategy | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMPARs [29,30,63,79] | Mediate most excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs); drive tumor microtubule (TM) formation and dynamics. | Perampanel (noncompetitive antagonist). | Reduces proliferation, invasion, and TMs formation. Under investigation for recurrent GBM (PerSurge trial). |

| xCT antiporter (SLC7A11) [5,29,30,79] | Responsible for massive non-synaptic glutamate release by glioma cells, causing excitotoxicity. | Sulfasalazine (inhibitor of xCT). | Reduces extracellular glutamate levels, decreasing tumor growth and alleviating excitotoxicity. Part of the GLUGLIO clinical trial. |

| NMDARs [6,29,30,79] | Activation promotes survival; antagonism increases radiosensitivity. | Memantine (noncompetitive antagonist). | May prevent neuron–glioma synapse formation. Being investigated in GLUGLIO trial. |

| NKCC1 cotransporter [30] | Overexpression in DMGs causes Cl− accumulation, making GABA signaling depolarizing/excitatory. | Bumetanide (NKCC1 inhibitor). | Counteracts the depolarizing effect of GABA, suggesting a pathway to reduce tumor growth. |

| ASIC1a channel [6] | Activated in surrounding neurons by the acidic tumor microenvironment (TME). Activation induces neurotransmitter release. | Genetic deletion or pharmacological inhibition of neuronal ASIC1a. | Deletion reduces tumor size and significantly prolongs survival in animal models. Effective against high-grade glioma progression. |

| α2δ-1 subunit (VSCC component) [22,29,30,79] | Receptor for synaptogenic factor TSP-1. Also binds gabapentinoids. | Gabapentin/Pregabalin. | Reduces synaptogenesis and proliferation. Included in the GLUGLIO trial. |

| KCa3.1 channel [30] | Responsible for rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations in “pacemaker-like” glioma cells. | Pharmacological blockade. | Suppresses autonomous network oscillations and prolongs survival in animal models. High expression associated with reduced survival in patients. |

| P2X7R [30] | Ligand-gated cation channel activated by extracellular ATP. Contributes to Ca2+ mobilization. | Antagonism or agonism (context dependent). | Activation increases proliferation/mobility and acts synergistically with AMPAR to increase Ca2+ influx. Inhibition can sometimes promote growth by upregulating EGFR. |

| T-type VGCCs (Cav3.1 channels) [30] | Ca2+ channels involved in proliferation and cell survival pathways (mTOR/Akt) in GBM stem-like cells. | Pharmacological blockade (e.g., Mibefradil). | Inhibition reduces cell survival/proliferation and induces apoptosis. Mibefradil was tested in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas. |

| Drug/Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Target Pathway | Clinical Trial Status | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perampanel [29,30,79] | Noncompetitive AMPAR antagonist. | AMPARs neuron–glioma synapse. | PerSurge trial (Phase II); Pilot trials in HGG. | Reduces proliferation, invasion, and TMs formation preclinically. Approved for seizures, safe perioperatively, but maintenance showed limited survival impact. |

| Sulfasalazine [5,30] | Inhibitor of glutamate release. | xCT antiporter (SLC7A11). | GLUGLIO trial (Phase Ib/II, combination). | Reduces pathological extracellular glutamate levels and excitotoxicity. Monotherapy lacked efficacy in Phase I. |

| Memantine [6,30] | Noncompetitive NMDAR antagonist. | NMDARs. | GLUGLIO trial (Phase Ib/II, combination). | May prevent synapse formation and increase radiosensitivity. Mild inhibitory effects may offer a better therapeutic window. |

| Gabapentin/Pregabalin [22,29,30,79] | α2δ-1 subunit binder. | Ca2+ channel auxiliary subunit TSP-1 signaling. | GLUGLIO trial (combination). | Reduces synaptogenesis, network synchrony, and proliferation by blocking TSP-1 binding to α2δ-1. |

| Bumetanide [30] | NKCC1 inhibitor. | NKCC1 Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter GABAergic depolarization. | Preclinical | Counteracts the depolarizing and growth-promoting effect of GABA in DMGs. |

| Antagonists (e.g., Perphenazine, ONC201) [30] | DRD2 inhibition. | DRD2. | Clinical trials (ONC201) in GBM. | Inactivates oncogenic MET/STAT3 signaling; induces TRAIL ligand-independent apoptosis by activating DR4/5 receptors. |

| Troriluzole [5,29,30,79] | Glutamate release modulator. | Glutamate reuptake Sodium channels. | GBM AGILE trial (Phase III) for GBM. | Reduces synaptic glutamate by enhancing reuptake and inhibiting release. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cueto-Ureña, C.; Ramírez-Expósito, M.J.; Martínez-Martos, J.M. Neuron–Glioma Synapses in Tumor Progression. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010072

Cueto-Ureña C, Ramírez-Expósito MJ, Martínez-Martos JM. Neuron–Glioma Synapses in Tumor Progression. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleCueto-Ureña, Cristina, María Jesús Ramírez-Expósito, and José Manuel Martínez-Martos. 2026. "Neuron–Glioma Synapses in Tumor Progression" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010072

APA StyleCueto-Ureña, C., Ramírez-Expósito, M. J., & Martínez-Martos, J. M. (2026). Neuron–Glioma Synapses in Tumor Progression. Biomedicines, 14(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010072