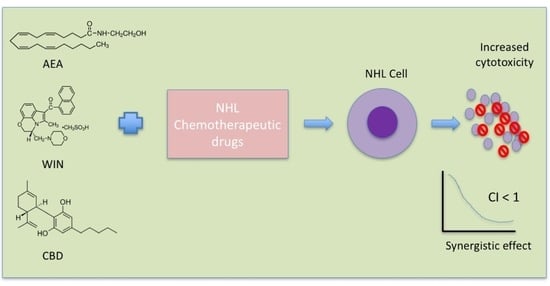

Cytotoxicity of Cannabinoids in Combination with Traditional Lymphoma Chemotherapeutic Drugs Against Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Chemicals

2.2. Cell Maintenance

2.3. IC50 Calculation

2.4. Drug Combination

2.5. Cell Viability

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Determination of IC50 for Cannabinoids and NLC Drugs in 1771 Lymphoma Cells

3.2. Combination of CBs and NLC Drugs Synergistically Caused the Death of 1771 B Lymphoma Cells

- Combination index plots for CBs + DOX:The AEADOX plot includes five data points, with four showing synergism (CI < 1) and one showing antagonism (CI > 1). CBDDOX similarly presents five data points, three being synergistic and two antagonistic. The WINDOX plot contains six data points, five demonstrating synergism and one showing an additive effect.

- Combination index plots for CBs + CYC:Both AEACYC and CBDCYC plots contain five data points, all demonstrating synergism (CI < 1), though all are at Fa > 0.5. The WINCYC plot shows six data points, five being synergistic and one antagonistic, again all simulated at Fa > 0.5.

- Combination index plots for CBs + VIN:The AEAVIN plot includes seven data points: four synergistic, two additive, and one antagonistic. CBDVIN presents six data points, with three showing synergism, one being additive, and two being antagonistic. The WINVIN plot includes six data points, five being synergistic and one antagonistic.

- Combination index plots for CBs + LOM:The AEALOM plot contains six data points, five being synergistic and one antagonistic, with the antagonistic point occurring at a low Fa value. CBDLOM shows six data points, four being synergistic, one being additive, and one being antagonistic. The WINLOM plot includes six data points, with three being synergistic and three antagonistic.

- Combination index plots for CBs + PRD:The AEAPRD plot includes seven data points, five being synergistic and two additive. CBDPRD presents six data points, all being synergistic (CI < 1). The WINPRD plot includes seven data points, with six demonstrating synergism and one being antagonistic.

3.3. CBs Combined with NLC Drugs at IC50 Synergistically Inhibited 1771 B-Cell Lymphoma Cell Growth

- CBs + DOX at IC50:CBD significantly potentiated DOX-induced inhibition of 1771 cell growth, demonstrating a synergistic effect at IC50. In contrast, AEA and WIN did not show synergistic activity with DOX at this concentration.

- CBs + CYC at IC50:No significant potentiating or synergistic effect of any CB on CYC-induced cytotoxicity was observed when the drugs were combined at their IC50 concentrations.

- CBs + VIN at IC50:All three CBs—AEA, CBD, and WIN—significantly enhanced VIN-induced inhibition of 1771 cell viability, indicating a synergistic effect at IC50.

- CBs + LOM at IC50:AEA, CBD, and WIN each significantly potentiated LOM-induced cytotoxicity in 1771 cells when combined at IC50.

- CBs + PRD at IC50:All three CBs significantly increased PRD-induced inhibition of 1771 cell growth at IC50.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBs | Cannabinoids |

| NHL | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| CHOP | Traditional chemotherapeutic regimen for NHL |

| AEA | Linear dichroism |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| WIN | WIN-55 212 22 |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| CYC | Cyclophosphamide |

| LOM | Lomustine |

| VIN | Vincristine |

| PRD | Prednisolone |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| CI | Combination index |

| MTT | Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide |

References

- Meng, J.; Guo, F.; Xu, H.; Liang, W.; Wang, C.; Yang, X.-D. Combination therapy using co-encapsulated resveratrol and paclitaxel in liposomes for drug resistance reversal in breast cancer cells in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galustian, C.; Dalgleish, A.G. Article Commentary: The power of the web in cancer drug discovery and clinical trial design: Research without a laboratory? Cancer Inform. 2010, 9, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehne, G. P-glycoprotein as a drug target in the treatment of multidrug resistant cancer. Curr. Drug Targets 2000, 1, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavi, O.; Gottesman, M.M.; Levy, D. The dynamics of drug resistance: A mathematical perspective. Drug Resist. Updates 2012, 15, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-M.J.; Zhang, L. Nanoparticle-based combination therapy toward overcoming drug resistance in cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiss, D.C.; Gabriels, G.A.; Folb, P.I. Combination of tunicamycin with anticancer drugs synergistically enhances their toxicity in multidrug-resistant human ovarian cystadenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2007, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, T. Clinical application of drug delivery systems in cancer chemotherapy: Review of the efficacy and side effects of approved drugs. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummar, S.; Chen, H.X.; Wright, J.; Holbeck, S.; Millin, M.D.; Tomaszewski, J.; Zweibel, J.; Collins, J.; Doroshow, J.H. Utilizing targeted cancer therapeutic agents in combination: Novel approaches and urgent requirements. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoya, K.; Kisseberth, W.C.; Lord, L.K.; Alvarez, F.J.; Lara-Garcia, A.; Kosarek, C.E.; London, C.A.; Couto, C.G. Comparison of COAP and UW-19 protocols for dogs with multicentric lymphoma. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2007, 21, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.S.; DesMarteau, P.; Hamilton, B.; Patthoff, S. Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; University of Richmond, Robins School of Business: Richmond, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mouhssine, S.; Maher, N.; Matti, B.F.; Alwan, A.F.; Gaidano, G. Targeting BTK in B cell malignancies: From mode of action to resistance mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehn, L.H.; Herrera, A.F.; Flowers, C.R.; Kamdar, M.K.; McMillan, A.; Hertzberg, M.; Assouline, S.; Kim, T.M.; Kim, W.S.; Ozcan, M.; et al. Polatuzumab vedotin in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budde, L.E.; Sehn, L.H.; Matasar, M.; Schuster, S.J.; Assouline, S.; Giri, P.; Kuruvilla, J.; Canales, M.; Dietrich, S.; Fay, K.; et al. Safety and efficacy of mosunetuzumab, a bispecific antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, S.S.; Locke, F.L.; Bartlett, N.L.; Lekakis, L.J.; Miklos, D.B.; Jacobson, C.A.; Braunschweig, I.; Oluwole, O.O.; Siddiqi, T.; Lin, Y.; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizeri, J.A.; Howell, K.; McKeever, K.P.; Crow, S.E. The role of rituximab in the treatment of canine lymphoma: An ex vivo evaluation. Vet. J. 2006, 171, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandvliet, M. Canine lymphoma: A review. Vet. Q. 2016, 36, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, A.; Witkowska, M.; Mędra, A.; Zwolińska, M.; Bogusz, J.; Cebula-Obrzut, B.; Darzynkiewicz, Z.; Robak, T.; Smolewski, P. In vitro cytotoxicity of ranpirnase (onconase) in combination with components of R-CHOP regimen against diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell line. Adv. Hyg. Exp. Med./Postep. Hig. Med. Dosw. 2013, 67, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M. Cannabinoids: Potential anticancer agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 745–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B.; Ramer, R. Anti-tumour actions of cannabinoids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramer, R.; Hinz, B. Cannabinoids as anticancer drugs. Adv. Pharmacol. 2017, 80, 397–436. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, M.L.; Panetta, J.A.; Hoskins, J.M.; Bebawy, M.; Roufogalis, B.D.; Allen, J.D.; Arnold, J.C. The effects of cannabinoids on P-glycoprotein transport and expression in multidrug resistant cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.; Pathak, S.; Nadar, R.; Bowen, D.; Sandey, M.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Pondugula, S.; Mansour, M.; Boothe, D. Validating the anti-lymphoma pharmacodynamic actions of the endocannabinoids on canine non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Life Sci. 2023, 327, 121862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.; Pathak, S.; Mansour, M.; Nadar, R.; Bowen, D.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Pondugula, S.R.; Boothe, D. Effects of cannabidiol, ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol, and WIN 55-212-22 on the viability of canine and human non-Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, F.; Schafer, D. The Statistical Sleuth: A Course in Methods of Data Analysis; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R.N. Sas. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2011, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-C. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.-C.; Talalay, P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: The combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 1984, 22, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, G.; Hernández-Tiedra, S.; Dávila, D.; Lorente, M. The use of cannabinoids as anticancer agents. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 64, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, S.A.; Stone, N.L.; Bellman, Z.D.; Yates, A.S.; England, T.J.; O’Sullivan, S.E. A systematic review of cannabidiol dosing in clinical populations. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 1888–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, A.; Lindgren, J.E.; Andersson, S.; Agurell, S.; Gillespie, H.; Hollister, L.E. Single-dose kinetics of deuterium-labelled cannabidiol in man after smoking and intravenous administration. Biomed. Env. Mass. Spectrom. 1986, 13, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.-y.; Pei, L.; Liu, Q.; Chen, S.; Dou, H.; Shu, G.; Yuan, Z.-x.; Lin, J.; Peng, G.; Zhang, W. Isobologram analysis: A comprehensive review of methodology and current research. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C.; Blume, L.C.; Dalton, G.D. CB(1) cannabinoid receptors and their associated proteins. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Jarocka-Karpowicz, I.; Skrzydlewska, E. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties of cannabidiol. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Hajj, K.A.; Knapp, C.M.; Whitehead, K.A. Development of a clinically relevant chemoresistant mantle cell lymphoma cell culture model. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, S.B.; Lindgren, T.; Jonsson, M.; Jacobsson, S.O. Cannabinoid receptor-independent cytotoxic effects of cannabinoids in human colorectal carcinoma cells: Synergism with 5-fluorouracil. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2009, 63, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andradas, C.; Byrne, J.; Kuchibhotla, M.; Ancliffe, M.; Jones, A.C.; Carline, B.; Hii, H.; Truong, A.; Storer, L.C.; Ritzmann, T.A. Assessment of cannabidiol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabiol in mouse models of medulloblastoma and ependymoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, T.; Rauvolfova, J.; Jackson, E.; Pham, L.V.; Bryant, J. Synergistic effect of cannabidiol with conventional chemotherapy treatment. Blood 2018, 132, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cannabinoids (CBs) Panel | NHL Chemotherapy Drugs Panel (NLC) |

|---|---|

Anandamide (AEA)—Endocannabinoid | Doxorubicin (DOX) |

Cyclophosphamide (CYC) | |

Cannabidiol (CBD)—Phytocannabinoid | Lomustine (LOM) |

Vincristine (VIN) | |

WIN 55-212 22 (WIN)—Synthetic Cannabinoid | Prednisolone (PRD) |

| Drug Combinations | CI Values at Corresponding Doses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | |

| AEA/DOX | 1.61992 | 0.66614 | 0.36450 | 0.42845 | 0.87930 | 2.02629 | 5.70658 |

| CBD/DOX | 1.76727 | 2.57811 | 0.95555 | 0.27889 | 0.56966 | 1.40582 | 12.9357 |

| WIN/DOX | 0.92142 | 0.50069 | 0.18778 | 0.25971 | 0.48934 | 1.08157 | 2.66036 |

| AEA/CYC | 0.23358 | 0.1704 | 0.30561 | 0.55785 | 0.94597 | 2.31856 | 4.33812 |

| CBD/CYC | 0.3133 | 0.17504 | 0.33841 | 0.50016 | 0.89482 | 2.00064 | 12.3526 |

| WIN/CYC | 0.36316 | 0.2129 | 0.26403 | 0.50293 | 0.93256 | 1.8816 | 2.77754 |

| AEA/VIN | 0.69691 | 1.07749 | 0.62071 | 0.29664 | 1.0893 | 0.829 | 1.76577 |

| CBD/VIN | 1.05909 | 1.29037 | 0.40006 | 0.57188 | 0.51804 | 1.20373 | 4.38346 |

| WIN/VIN | 0.96306 | 0.60887 | 0.28864 | 0.51851 | 0.77303 | 1.25329 | 2.03859 |

| AEA/LOM | 0.62206 | 0.73607 | 0.92653 | 0.75897 | 0.94603 | 1.20716 | 2.4846 |

| CBD/LOM | 0.80517 | 1.05218 | 0.97975 | 0.65612 | 0.6996 | 1.47968 | 5.22987 |

| WIN/LOM | 1.25745 | 1.19752 | 0.49299 | 0.59787 | 0.87586 | 1.23573 | 2.37321 |

| AEA/PRD | 0.3966 | 0.63436 | 1.1947 | 1.11198 | 0.35895 | 0.2973 | 0.81838 |

| CBD/PRD | 0.34493 | 0.46539 | 0.48758 | 0.31461 | 0.44162 | 0.92014 | 2.60304 |

| WIN/PRD | 0.70135 | 0.36793 | 0.16719 | 0.26345 | 0.39777 | 0.58383 | 1.25507 |

| Combination Index (CI) at 50–95% Effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Combination | ED50 | ED75 | ED90 | ED95 |

| AEA/DOX | 0.78232 | 0.34562 | 0.17554 | 0.11614 |

| CBD/DOX | 0.62255 | 0.28710 | 0.13356 | 0.07974 |

| WIN/DOX | 0.45266 | 0.21730 | 0.10565 | 0.06518 |

| AEA/CYC | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CBD/CYC | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| WIN/CYC | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AEA/VIN | 0.66737 | 0.52721 | 0.41795 | 0.35757 |

| CBD/VIN | 0.66684 | 0.43908 | 0.28932 | 0.21794 |

| WIN/VIN | 0.46094 | 0.28730 | 0.18033 | 0.13186 |

| AEA/LOM | 0.98415 | 0.75361 | 0.57993 | 0.48661 |

| CBD/LOM | 0.92988 | 0.58054 | 0.36441 | 0.26628 |

| WIN/LOM | 0.92655 | 0.78793 | 0.67335 | 0.60671 |

| AEA/PRD | 0.41611 | 34.6162 | 10311.2 | 497964. |

| CBD/PRD | 0.46768 | 0.89025 | 4.48310 | 14.9966 |

| WIN/PRD | 0.26785 | 0.59590 | 6.96326 | 42.1908 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Omer, S.; Mansour, M.; Pondugula, S.R.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Matz, B.; Khan, O.; Boothe, D. Cytotoxicity of Cannabinoids in Combination with Traditional Lymphoma Chemotherapeutic Drugs Against Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010003

Omer S, Mansour M, Pondugula SR, Dhanasekaran M, Matz B, Khan O, Boothe D. Cytotoxicity of Cannabinoids in Combination with Traditional Lymphoma Chemotherapeutic Drugs Against Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmer, Saba, Mahmoud Mansour, Satyanarayana R Pondugula, Muralikrishnan Dhanasekaran, Brad Matz, Omer Khan, and Dawn Boothe. 2026. "Cytotoxicity of Cannabinoids in Combination with Traditional Lymphoma Chemotherapeutic Drugs Against Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010003

APA StyleOmer, S., Mansour, M., Pondugula, S. R., Dhanasekaran, M., Matz, B., Khan, O., & Boothe, D. (2026). Cytotoxicity of Cannabinoids in Combination with Traditional Lymphoma Chemotherapeutic Drugs Against Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Biomedicines, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010003