GalNAc-Transferases in Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

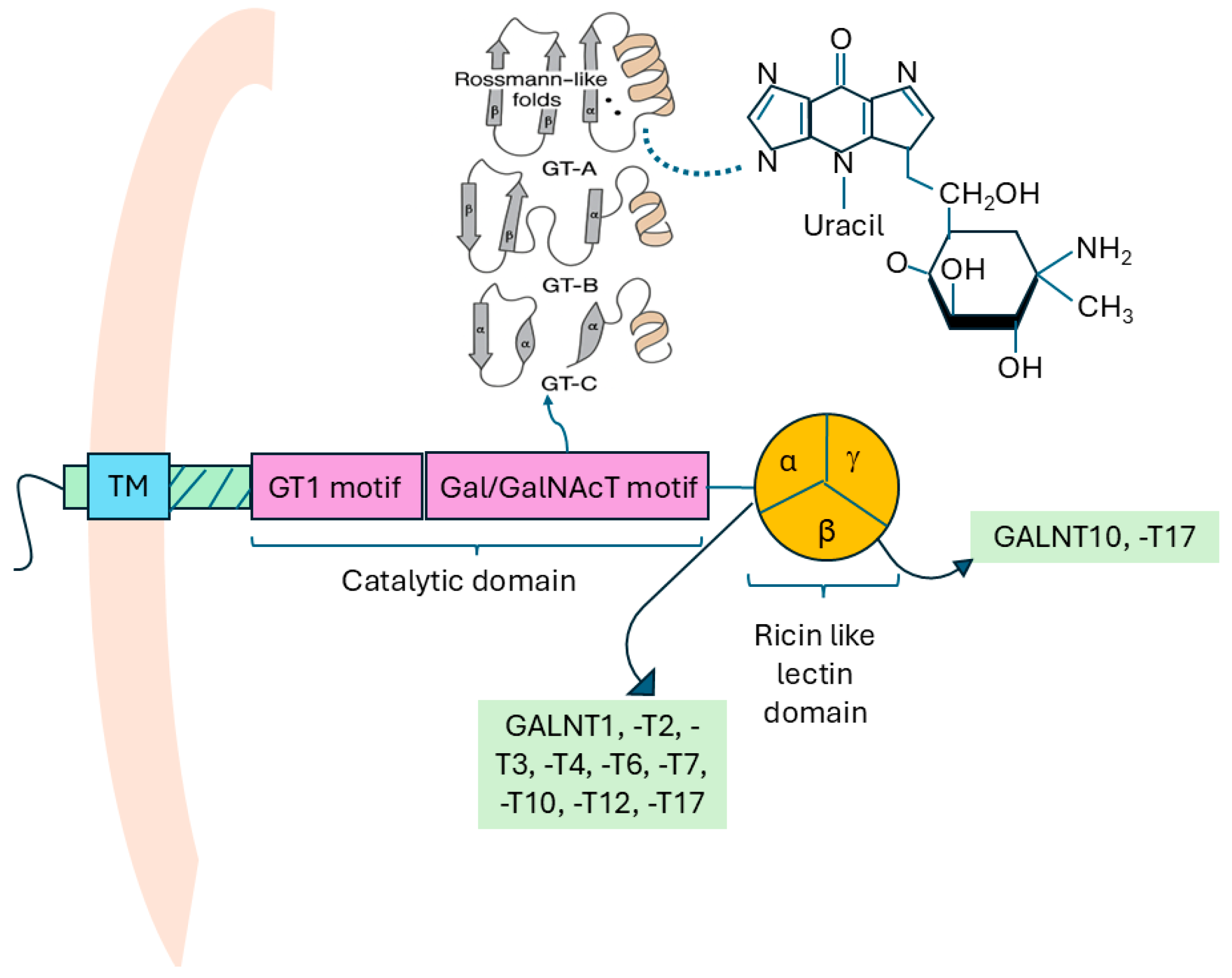

1.1. Structure of GALNTs

1.2. Types of GALNTs and the Human GALNT Gene Family

1.3. Substrate Specificities of GALNTs

1.4. Expression of GALNTs

1.5. Role of Golgi Apparatus in GALNT Activity

2. Role of GALNTs in Cancers

2.1. EGFR-Mediated Pathway

2.2. TGF-β Signaling Pathway and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

2.3. Notch Signaling and GALNTs

2.4. GALNT and Immune Evasion in Cancers

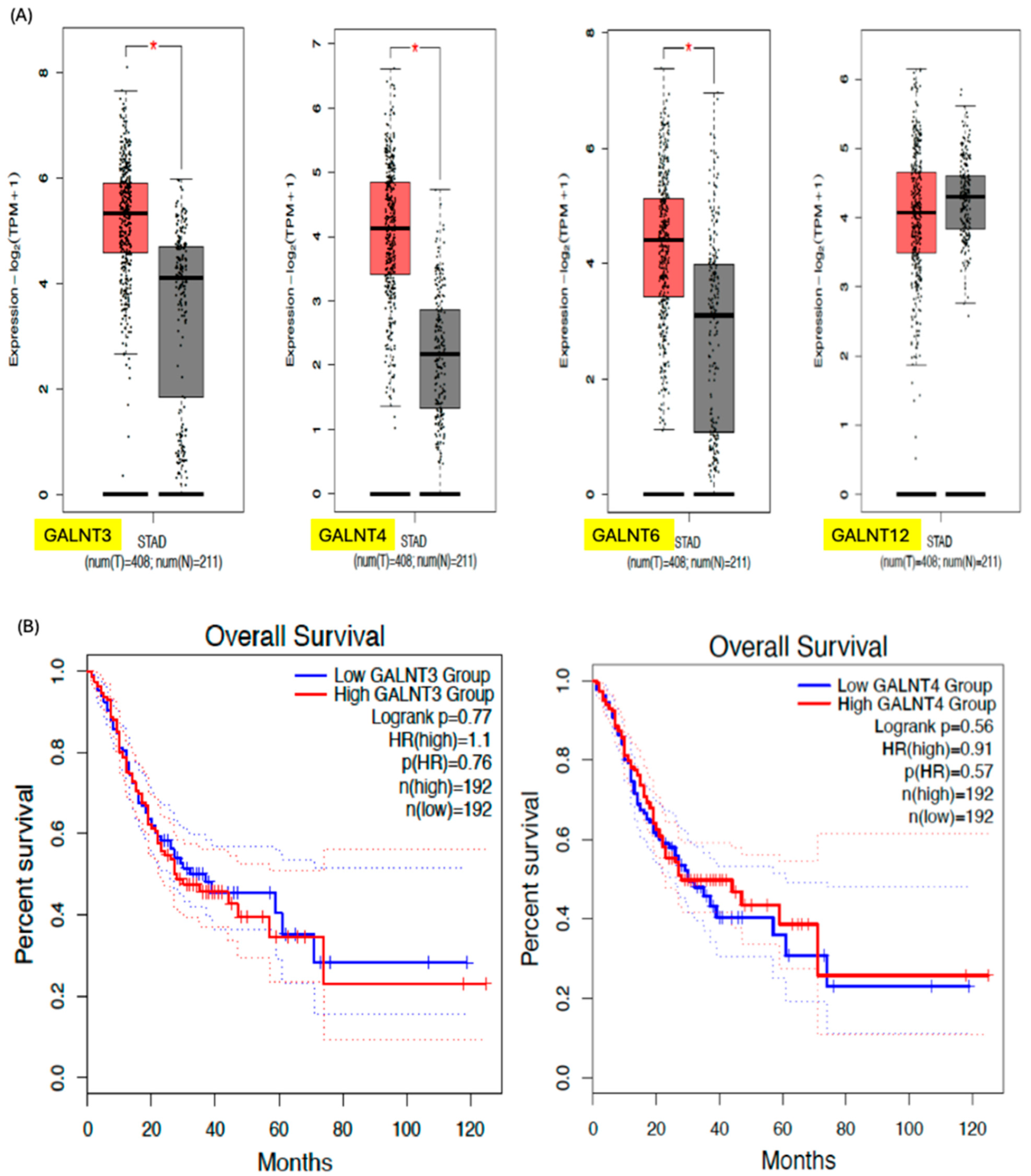

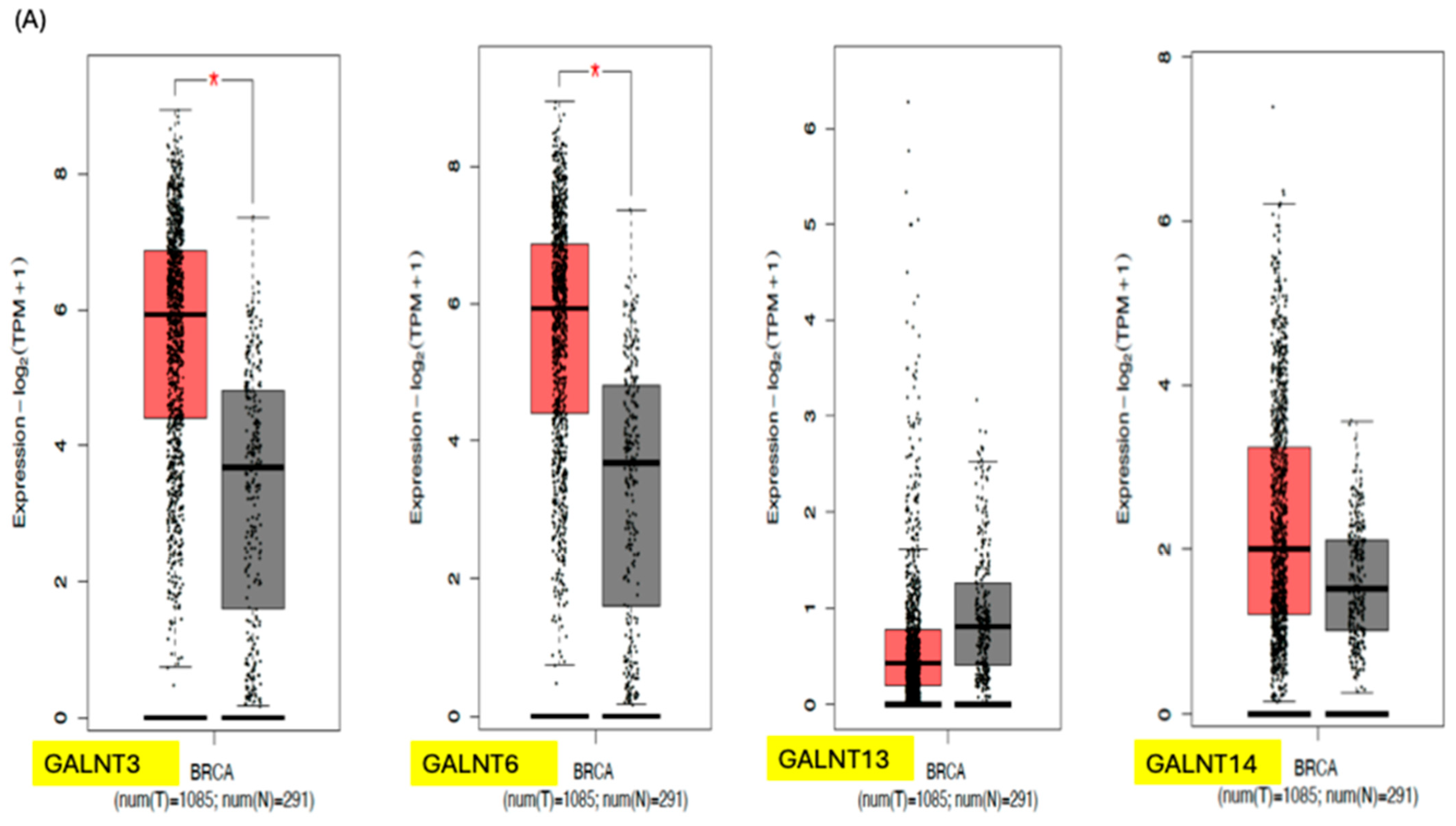

3. GALNTs as Prognostic Markers in Cancer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AKT | Ak strain transforming |

| BMP | Bone morphogenetic protein |

| C1GALT1 | Core 1 synthase, glycoprotein-N-acetylgalactosamine 3-beta-galactosyltransferase 1 |

| CCL5 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 5 |

| CGN | Cis-Golgi network |

| c-Jun | Transcription factor Jun |

| COPI | Coat Protein I |

| COSMC | Core-1 β1-3galactosyltransferase-specific chaperone 1 |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| CXCL10 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 |

| EGF | Epithelial growth factor |

| EGFR | Epithelial growth factor receptors |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ErbB | Erythroblastic oncogene B |

| ERK8 | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 8 |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box O1 transcription factor |

| FUT | Fucosyltransferase |

| GALA | GALNT activation |

| GALNT | N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase |

| GlcNAc | N-Acetylglucosamine |

| GMP-AMP | Guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate |

| GT | Glycosyltransferase |

| GT-A | Glycosyltransferase fold A |

| GT-B | Glycosyltransferase fold B |

| GT-C | Glycosyltransferase fold C |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Her2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| KRAS | Kirsten ras oncogene homolog |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MUC1 | Mucin-1 |

| NICD | Notch intracellular domain |

| onfFN | Oncofetal fibronectin |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| Ser | Serine |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| SLUG | SNAI2 gene |

| SNAIL | Zinc finger protein SNAI1 |

| ST3Gal | ST3 beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase 1 |

| STING | Stimulator of interferon genes |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| Thr | Threonine |

| Tn | Thomsen-nouveau |

| TGN | Trans-Golgi network |

| TME | Tumour microenvironment |

| UBE2C | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2C |

| UDP-GalNAc | Uridine diphosphate N-acetylgalactosamine |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VTC | Vesicular tubular clusters |

| VVA | Vicia villosa Lectin |

| ZEB1 | Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 |

References

- Eichler, J. Protein glycosylation. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R229–R231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, P.V.D.; Rudd, P.M.; Dwek, R.A.; Opdenakker, G. Concepts and principles of O-linked glycosylation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998, 33, 151–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounsell, E.F.; Davies, M.J.; Renouf, D.V. O-linked protein glycosylation structure and function. Glycoconj. J. 1996, 13, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.P.; Mandel, U.; Clausen, H.; Gerken, T.A.; Fritz, T.A.; Tabak, L.A. Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: A classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 736–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.; Parameswaran, R. Role of Truncated O-GalNAc Glycans in Cancer Progression and Metastasis in Endocrine Cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munkley, J.; Elliott, D.J. Hallmarks of glycosylation in cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 35478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meany, D.L.; Chan, D.W. Aberrant glycosylation associated with enzymes as cancer biomarkers. Clin. Proteom. 2011, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, J.C.; Colley, K.J. Glycosyltransferases: Structure, localization, and control of cell type-specific glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 17615–17618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, R.; Drickamer, K. Lectin-like proteins in model organisms: Implications for evolution of carbohydrate-binding activity. Glycobiology 2001, 11, 71R–79R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, F.K.; Hazes, B.; Raffo, R.; DeSa, D.; Tabak, L.A. Structure-Function Analysis of the UDP-N-acetyl-d-galactosamine: PolypeptideN-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase: Essential Residues Lie In A Predicted Active Site Cleft Resembling a Lactose Repressor Fold. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 6797–6803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, Y.; Henrissat, B. Glycoside hydrolases and glycosyltransferases: Families and functional modules. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001, 11, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A.; Cummings, R.D.; Esko, J.D.; Stanley, P.; Hart, G.W.; Aebi, M.; Darvill, A.G.; Kinoshita, T.; Packer, N.H.; Prestegard, J.H. Essentials of Glycobiology [Internet], 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Varki, A.; Cummings, R.D.; Esko, J.D.; Stanley, P.; Hart, G.W.; Aebi, M.; Mohnen, D.; Kinoshita, T.; Packer, N.H.; Prestegard, J.H. Essentials of Glycobiology [Internet], 4th ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, D.J.; Tham, K.M.; Chia, J.; Wang, S.C.; Steentoft, C.; Clausen, H.; Bard-Chapeau, E.A.; Bard, F.A. Initiation of GalNAc-type O-glycosylation in the endoplasmic reticulum promotes cancer cell invasiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E3152–E3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.; Wang, S.C.; Wee, S.; Gill, D.J.; Tay, F.; Kannan, S.; Verma, C.S.; Gunaratne, J.; Bard, F.A. Src activates retrograde membrane traffic through phosphorylation of GBF1. Elife 2021, 10, e68678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, S.; De Luca, V.; Parizadeh, S.; Russo, D.; Luini, A.; Di Martino, R. Endogenous and Exogenous Regulatory Signaling in the Secretory Pathway: Role of Golgi Signaling Molecules in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 833663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, K.G.T.; Fritz, T.A.; Tabak, L.A. All in the family: The UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 1r–16r. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, S.P.; Srinivasan, Y.; Labonte, J.W.; DeLisa, M.P.; Gray, J.J. Structural basis for peptide substrate specificities of glycosyltransferase GalNAc-T2. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 2977–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, T.A.; Raman, J.; Fritz, T.A.; Jamison, O. Identification of common and unique peptide substrate preferences for the UDP-GalNAc: Polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases T1 and T2 derived from oriented random peptide substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 32403–32416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerken, T.A.; Jamison, O.; Perrine, C.L.; Collette, J.C.; Moinova, H.; Ravi, L.; Markowitz, S.D.; Shen, W.; Patel, H.; Tabak, L.A. Emerging paradigms for the initiation of mucin-type protein O-glycosylation by the polypeptide GalNAc transferase family of glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 14493–14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Liu, C.H.; Hu, R.H.; Huang, M.J.; Lee, J.J.; Chen, C.H.; Huang, J.; Lai, H.S.; Lee, P.H.; Hsu, W.M.; et al. Mucin glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 regulates the malignant character of hepatocellular carcinoma by modifying the EGF receptor. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 7270–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, T.E.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Exploring the combined roles of GALNT1 and GALNT2 in hepatocellular carcinoma malignancy and EGFR modulation. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.-J.; Hu, R.-H.; Chou, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-L.; Liu, Y.-W.; Huang, J.; Hung, J.-S.; Lai, I.-R.; Juan, H.-F.; Yu, S.-L.; et al. Knockdown of GALNT1 suppresses malignant phenotype of hepatocellular carcinoma by suppressing EGFR signaling. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 5650–5665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Bachvarova, M.; Morin, C.; Plante, M.; Gregoire, J.; Renaud, M.C.; Sebastianelli, A.; Bachvarov, D. Role of the polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3 in ovarian cancer progression: Possible implications in abnormal mucin O-glycosylation. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheta, R.; Woo, C.M.; Roux-Dalvai, F.; Fournier, F.; Bourassa, S.; Droit, A.; Bertozzi, C.R.; Bachvarov, D. A metabolic labeling approach for glycoproteomic analysis reveals altered glycoprotein expression upon GALNT3 knockdown in ovarian cancer cells. J. Proteom. 2016, 145, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-w.; Liu, M.-b.; Jiang, X.; Song, T.; Feng, S.-x.; Wu, J.-y.; Deng, P.-f.; Wang, X.-y. GALNT14 Regulates Ferroptosis and Apoptosis of Ovarian Cancer Through the EGFR/mTOR Pathway. Future Oncol. 2022, 18, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, J.; Wei, S.; Xing, C. GALNT4-induced O-GalNAc glycosylation of MUC1 accelerates the invasive phenotype of PDAC. Pancreatology 2025, 25, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, S.; Hou, K.; Fan, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; et al. GALNT6 promotes breast cancer metastasis by increasing mucin-type O-glycosylation of α2M. Aging 2020, 12, 11794–11811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Katagiri, T.; Chung, S.; Kijima, K.; Nakamura, Y. Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 6 disrupts mammary acinar morphogenesis through O-glycosylation of fibronectin. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.; Hodgson, K.; Calle, B.; Turner, H.; Cheung, K.; Bermudez, A.; Marques, F.J.G.; Pye, H.; Yo, E.C.; Islam, K.; et al. Upregulation of GALNT7 in prostate cancer modifies O-glycosylation and promotes tumour growth. Oncogene 2023, 42, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkley, J.; Vodak, D.; Livermore, K.E.; James, K.; Wilson, B.T.; Knight, B.; McCullagh, P.; McGrath, J.; Crundwell, M.; Harries, L.W.; et al. Glycosylation is an Androgen-Regulated Process Essential for Prostate Cancer Cell Viability. EBioMedicine 2016, 8, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teslovich, T.M.; Musunuru, K.; Smith, A.V.; Edmondson, A.C.; Stylianou, I.M.; Koseki, M.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Ripatti, S.; Chasman, D.I.; Willer, C.J.; et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature 2010, 466, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schjoldager, K.T.; Narimatsu, Y.; Joshi, H.J.; Clausen, H. Global view of human protein glycosylation pathways and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, T.D.; Hansen, L.H.; Hintze, J.; Ye, Z.; Jebari, S.; Andersen, D.B.; Joshi, H.J.; Ju, T.; Goetze, J.P.; Martin, C.; et al. An atlas of O-linked glycosylation on peptide hormones reveals diverse biological roles. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuselmann, I.; Borsig, L. Altered tumor-cell glycosylation promotes metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ju, T.; Ding, X.; Xia, B.; Wang, W.; Xia, L.; He, M.; Cummings, R.D. Cosmc is an essential chaperone for correct protein O-glycosylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9228–9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, T.; Aryal, R.P.; Stowell, C.J.; Cummings, R.D. Regulation of protein O-glycosylation by the endoplasmic reticulum-localized molecular chaperone Cosmc. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 182, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, T.; Lanneau, G.S.; Gautam, T.; Wang, Y.; Xia, B.; Stowell, S.R.; Willard, M.T.; Wang, W.; Xia, J.Y.; Zuna, R.E.; et al. Human tumor antigens Tn and sialyl Tn arise from mutations in Cosmc. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, D.J.; Chia, J.; Senewiratne, J.; Bard, F. Regulation of O-glycosylation through Golgi-to-ER relocation of initiation enzymes. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, N.T.; Pinho, S.; Grandela, C.; Cruz, A.; Samyn-Petit, B.; Harduin-Lepers, A.; Almeida, R.; Silva, F.; Morais, V.; Costa, J.; et al. Role of the human ST6GalNAc-I and ST6GalNAc-II in the synthesis of the cancer-associated sialyl-Tn antigen. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7050–7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, D.; Mobley, R.J.; Shendy, N.A.M.; Perry, C.H.; Abell, A.N. GALNT3 Maintains the Epithelial State in Trophoblast Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3684–3697.e3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumperman, J. Architecture of the mammalian Golgi. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a005181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladinsky, M.S.; Mastronarde, D.N.; McIntosh, J.R.; Howell, K.E.; Staehelin, L.A. Golgi structure in three dimensions: Functional insights from the normal rat kidney cell. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 144, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szul, T.; Sztul, E. COPII and COPI traffic at the ER-Golgi interface. Physiology 2011, 26, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, A.; Kunii, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Sumi, T.; Kanda, S.; Zhang, Y.; Nadanaka, S.; Hirosawa, K.M.; Tokunaga, K.; Tojima, T.; et al. Dynamic movement of the Golgi unit and its glycosylation enzyme zones. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4514–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, J.; Taatjes, D.J.; Lucocq, J.M.; Weinstein, J.; Paulson, J.C. Demonstration of an extensive trans-tubular network continuous with the Golgi apparatus stack that may function in glycosylation. Cell 1985, 43, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röttger, S.; White, J.; Wandall, H.H.; Olivo, J.C.; Stark, A.; Bennett, E.P.; Whitehouse, C.; Berger, E.G.; Clausen, H.; Nilsson, T. Localization of three human polypeptide GalNAc-transferases in HeLa cells suggests initiation of O-linked glycosylation throughout the Golgi apparatus. J. Cell Sci. 1998, 111, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.K.; Varki, A. The biosynthesis of oligosaccharides in intact Golgi preparations from rat liver. Analysis of N-linked and O-linked glycans labeled by UDP-[6-3H]N-acetylgalactosamine. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 16170–16178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, D.J.; Clausen, H.; Bard, F. Location, location, location: New insights into O-GalNAc protein glycosylation. Trends Cell Biol. 2011, 21, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerken, T.A.; Owens, C.L.; Pasumarthy, M. Site-specific core 1 O-glycosylation pattern of the porcine submaxillary gland mucin tandem repeat. Evidence for the modulation of glycan length by peptide sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 26580–26588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaz, O.; Shurman, D.L.; Bergman, R.; Indelman, M.; Ratajczak, P.; Mizrachi, M.; Khamaysi, Z.; Behar, D.; Petronius, D.; Friedman, V.; et al. Mutations in GALNT3, encoding a protein involved in O-linked glycosylation, cause familial tumoral calcinosis. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 579–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockhausen, I. Mucin-type O-glycans in human colon and breast cancer: Glycodynamics and functions. EMBO Rep. 2006, 7, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, J.; Tay, F.; Bard, F. The GalNAc-T Activation (GALA) Pathway: Drivers and markers. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, J.; Tham, K.M.; Gill, D.J.; Bard-Chapeau, E.A.; Bard, F.A. ERK8 is a negative regulator of O-GalNAc glycosylation and cell migration. Elife 2014, 3, e01828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.R.; Hoessli, D.C.; Fang, M. N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases in cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 54067–54081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaman, E.-M.; Carter, D.R.F.; Brooks, S.A. GALNTs: Master regulators of metastasis-associated epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)? Glycobiology 2022, 32, 556–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaman, E.M.; Brooks, S.A. The extended ppGalNAc-T family and their functional involvement in the metastatic cascade. Histol. Histopathol. 2014, 29, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.T.; Yeh, C.C.; Liu, S.Y.; Huang, M.C.; Lai, I.R. The O-glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 suppresses the malignancy of gastric adenocarcinoma by reducing EGFR activities. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2018, 8, 1739–1751. [Google Scholar]

- Detarya, M.; Lert-Itthiporn, W.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Klaewkla, M.; Sorin, S.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Silsirivanit, A.; Seubwai, W.; Wongkham, C.; Araki, N.; et al. Emerging roles of GALNT5 on promoting EGFR activation in cholangiocarcinoma: A mechanistic insight. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 4140–4159. [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, S.; Meza, J.; Sheinin, Y.M.; Ponnusamy, M.P.; Batra, S.K. Loss of N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 3 in poorly differentiated pancreatic cancer: Augmented aggressiveness and aberrant ErbB family glycosylation. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dijke, P.T.; Wuhrer, M.; Zhang, T. Role of glycosylation in TGF-β signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Protein. Cell 2020, 12, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aashaq, S.; Batool, A.; Mir, S.A.; Beigh, M.A.; Andrabi, K.I.; Shah, Z.A. TGF-β signaling: A recap of SMAD-independent and SMAD-dependent pathways. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, H.; Ackland, M.L.; Blick, T.; Lawrence, M.G.; Clements, J.A.; Williams, E.D.; Thompson, E.W. Epithelial--mesenchymal and mesenchymal--epithelial transitions in carcinoma progression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 213, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; Weinberg, R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Q.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; Huang, T.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; et al. ppGalNAc-T4-catalyzed O-Glycosylation of TGF-β type II receptor regulates breast cancer cells metastasis potential. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Shun, C.T.; Hung, K.Y.; Juan, H.F.; Hsu, C.L.; Huang, M.C.; Lai, I.R. Mucin glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 suppresses malignancy in gastric adenocarcinoma by reducing MET phosphorylation. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 11251–11262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.Y.; Chuang, Y.T.; Lin, H.Y.; Lin, N.Y.; Hsu, T.W.; Hsieh, S.C.; Chen, S.T.; Hung, J.S.; Yang, H.J.; Liang, J.T.; et al. GALNT2 promotes invasiveness of colorectal cancer cells partly through AXL. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Tian, T.; Leng, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, S.; Lv, Y.; Liang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Shen, L.; et al. The O-glycosylating enzyme GALNT2 acts as an oncogenic driver in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huanna, T.; Tao, Z.; Xiangfei, W.; Longfei, A.; Yuanyuan, X.; Jianhua, W.; Cuifang, Z.; Manjing, J.; Wenjing, C.; Shaochuan, Q.; et al. GALNT14 mediates tumor invasion and migration in breast cancer cell MCF-7. Mol. Carcinog. 2015, 54, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-de-Lima, L.; Gelfenbeyn, K.; Ding, Y.; Mandel, U.; Clausen, H.; Handa, K.; Hakomori, S.I. Involvement of O-glycosylation defining oncofetal fibronectin in epithelial-mesenchymal transition process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17690–17695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, E.; Weller, M.; Macnair, W.; Eschbach, K.; Beisel, C.; Cordazzo, C.; Claassen, M.; Zardi, L.; Burghardt, I. TGF-β induces oncofetal fibronectin that, in turn, modulates TGF-β superfamily signaling in endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs209619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolós, V.; Blanco, M.; Medina, V.; Aparicio, G.; Díaz-Prado, S.; Grande, E. Notch signalling in cancer stem cells. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2009, 11, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, L.; Golde, T.; Osborne, B. Notch Signaling in Cancer. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Niknejad, N.; Jafar-Nejad, H. Multifaceted regulation of Notch signaling by glycosylation. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, N.; Kang, Y. Notch signalling in cancer progression and bone metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 1805–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskovski, M.T.; Yuan, S.; Pedersen, N.B.; Goth, C.K.; Makova, S.; Clausen, H.; Brueckner, M.; Khokha, M.K. The heterotaxy gene GALNT11 glycosylates Notch to orchestrate cilia type and laterality. Nature 2013, 504, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, R.; Zeng, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Cao, S.; Deng, S.; Meng, X.; Yang, S. GALNT2 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by activating the Notch/Hes1-PTEN-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. Life Sci. 2021, 276, 119439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, C.; Sun, R.; Ji, D.; Wu, M.; Fu, Q.; Mei, L.; Wu, Z. Mechanism of the GALNT family proteins in regulating tumorigenesis and development of lung cancer (Review). Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libisch, M.G.; Casás, M.; Chiribao, M.; Moreno, P.; Cayota, A.; Osinaga, E.; Oppezzo, P.; Robello, C. GALNT11 as a new molecular marker in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Gene 2014, 533, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.A.; Carter, T.M.; Bennett, E.P.; Clausen, H.; Mandel, U. Immunolocalisation of members of the polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase (ppGalNAc-T) family is consistent with biologically relevant altered cell surface glycosylation in breast cancer. Acta. Histochem. 2007, 109, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesche, F.; Kölbl, A.C.; Ilmer, M.; Hutter, S.; Jeschke, U.; Andergassen, U. Role of N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 6 in early tumorigenesis and formation of metastasis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 4309–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, Y.E.; Kato, T.; Jang, M.; Haga, Y.; Ueda, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Park, J.H. Morphological Changes, Cadherin Switching, and Growth Suppression in Pancreatic Cancer by GALNT6 Knockdown. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, J.; Marcos, N.T.; Berois, N.; Osinaga, E.; Magalhães, A.; Pinto-de-Sousa, J.; Almeida, R.; Gärtner, F.; Reis, C.A. Expression of UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-6 in gastric mucosa, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric carcinoma. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 57, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, L.; Lei, C.; Li, W.; Han, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. A Sweet Warning: Mucin-Type O-Glycans in Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Wu, H.; Tang, L.; Al-Danakh, A.; Jian, Y.; Gong, L.; Li, C.; Yu, X.; Zeng, G.; Chen, Q.; et al. GALNT6 promotes bladder cancer malignancy and immune escape by epithelial-mesenchymal transition and CD8(+) T cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, S.; Liu, Y.; Bian, Z.; Hu, D.; Guo, S.; Dong, C.; Zeng, J.; Fan, S.; Chen, X. GALNT6 dual regulates innate immunity STING signaling and PD-L1 expression to promote immune evasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cell. Signal. 2025, 134, 111942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Ji, L.; Lv, C.; Zhao, C.; Ma, R.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Pan, L. Integrated multi-omics analysis reveals PTM networks as key regulators of colorectal cancer progression and immune evasion. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.H.; Park, M.S.; Nandu, T.S.; Gadad, S.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, M.Y. GALNT14 promotes lung-specific breast cancer metastasis by modulating self-renewal and interaction with the lung microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Yang, A.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.K.; Roe, J.-s.; Park, M.-S.; Oh, M.J.; An, H.J.; Kim, M.-Y. GALNT3 suppresses lung cancer by inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cell infiltration and angiogenesis in a TNFR and c-MET pathway-dependent manner. Cancer Lett. 2021, 521, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Burdette, J.E.; Wang, J.-P. Integrative network analysis of TCGA data for ovarian cancer. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjoldager, K.T.; Joshi, H.J.; Kong, Y.; Goth, C.K.; King, S.L.; Wandall, H.H.; Bennett, E.P.; Vakhrushev, S.Y.; Clausen, H. Deconstruction of O-glycosylation--GalNAc-T isoforms direct distinct subsets of the O-glycoproteome. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, R.; Yoshimaru, T.; Matsushita, Y.; Matsuo, T.; Ono, M.; Park, J.H.; Sasa, M.; Miyoshi, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Katagiri, T. The GALNT6-LGALS3BP axis promotes breast cancer cell growth. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 56, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.; Ubillos, L.; Elgul, N.; Festari, M.F.; Mazal, D.; Pritsch, O.; Alonso, I.; Osinaga, E.; Berois, N. Polypeptide-GalNAc-Transferase-13 Shows Prognostic Impact in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibao, K.; Izumi, H.; Nakayama, Y.; Ohta, R.; Nagata, N.; Nomoto, M.; Matsuo, K.; Yamada, Y.; Kitazato, K.; Itoh, H.; et al. Expression of UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine-polypeptide galNAc N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase-3 in relation to differentiation and prognosis in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 2002, 94, 1939–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Lu, J.; Zou, X.; Zhang, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, F.; Shan, A.; Lu, J.; Zheng, M.; et al. The polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 4 exhibits stage-dependent expression in colorectal cancer and affects tumorigenesis, invasion and differentiation. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3041–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubillos, L.; Berriel, E.; Mazal, D.; Victoria, S.; Barrios, E.; Osinaga, E.; Berois, N. Polypeptide-GalNAc-T6 expression predicts better overall survival in patients with colon cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.M.; Chen, H.L.; Wang, G.M.; Zhang, Y.K.; Narimatsu, H. Expression of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-12 in gastric and colonic cancer cell lines and in human colorectal cancer. Oncology 2004, 67, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onitsuka, K.; Shibao, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Minagawa, N.; Hirata, K.; Izumi, H.; Matsuo, K.; Nagata, N.; Kitazato, K.; Kohno, K.; et al. Prognostic significance of UDP-N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-3 (GalNAc-T3) expression in patients with gastric carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2003, 94, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y. Clinical significance of polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase-5 (GalNAc-T5) expression in patients with gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2021–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Liu, B.; Guo, H. Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-6 expression in gastric cancer. Onco. Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Wu, Y.L.; Li, N.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.B.; Ming, H.; Zhang, Y. GALNT10 promotes the proliferation and metastatic ability of gastric cancer and reduces 5-fluorouracil sensitivity by activating HOXD13. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 11610–11619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Nakamori, S.; Tsujie, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Nagano, H.; Dono, K.; Umeshita, K.; Sakon, M.; Tomita, Y.; Hoshida, Y.; et al. Expression of uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-alpha-D-galactosamine: Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase 3 in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Pathobiology 2004, 71, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Gong, H.; Han, S.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. GALNT5 functions as a suppressor of ferroptosis and a predictor of poor prognosis in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2023, 13, 4579–4596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Yamada, S.; Inenaga, S.; Imamura, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Shimajiri, S.; Nakano, R.; Izumi, H.; Kohno, K.; et al. Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 6 expression in pancreatic cancer is an independent prognostic factor indicating better overall survival. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1882–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Ito, K.; Izumi, H.; Kohno, K.; Amano, J. Expression of polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferase-3 and its association with clinicopathological factors in thyroid carcinomas. Thyroid 2013, 23, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GALNT | Human Tissues Expressed in | Family Subclassification | Chromosome Locus |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Widely distributed | Ia | 18q12.1 |

| T2 | Widely distributed | Ib | 1q41–q42 |

| T3 | Bone, sperm | Ic | 2q24–q31 |

| T4 | Lung | IIa | 12q21.33 |

| T5 | Stomach | Id | 2q24.1 |

| T6 | Stomach, colon | Ic | 12q13 |

| T7 | Sublingual gland | IIb | 4q34.1 |

| T8 | Colon, testes | Ie | 12p13.3 |

| T9 | Brain | Ie | 12q24.33 |

| T10 | Kidney | IIb | 5q33.2 |

| T11 | Prostate | If | 7q36.1 |

| T12 | Colon | IIa | 9q22.33 |

| T13 | Brain | Ia | 2q24.1 |

| T14 | Kidney | Ib | 2p23.1 |

| T15 | Placenta | Id | 3p25.1 |

| T16 | Brain, heart | Ib | 14q24.1 |

| T17 | Brain, ovary | IIb | 4q34.1 |

| T18 | Widely distributed | Ie | 11p15.3 |

| T19 | Brain | Ie | 7q11.23 |

| T20 | Testes | If | 7q36.1 |

| GALNT Isoform | Tissue Involved | Substrate or Pathway Involved | Functional Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GALNT1 and -T2 | Hepatocellular cancer | EGFR | Modifies the activity of EGFR; dysregulation leads to malignant behavior | [21,22,23] |

| GALNT3 and -T14 | Ovarian cancer | MUC1; EGFR/mTOR | Increased activity leads to increased MUC1 expression, resulting in increased cell proliferation, cell migration, and invasion | [24,25,26] |

| GALNT4 | Pancreatic cancer | MUC1 | Induces O-GalNAc glycosylation of MUC1 to enhance MUC1 protein stability | [27] |

| GALNT6 | Breast cancer | MUC1 & MUC4, α2-macroglobulin | Drives clustered O-GalNAc addition; activates PI3K/Akt signaling to increase invasion and tumor growth | [28,29] |

| GALNT7 | Prostate cancer | FOXO1, androgen regulator | Upregulation affects immune activity and cell signaling | [30,31] |

| GALNT Isoform | Tumor Role | Mechanism | Primary Cancer | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GALNT1 | Oncogenic | Glycosylates Notch to induce EMT and metastasis | Breast | [56] |

| GALNT2 | Oncogenic | Activates Notch/Hes1-PI3K/ Akt axis | Lung | [77] |

| GALNT2 | Suppressive | Maintains glycan profile; suppresses invasion | Gastric | [58] |

| GALNT3 | Suppressive | Suppresses Wnt via TNFR1 and c-MET glycosylation | Lung | [89] |

| GALNT6 | Oncogenic | Alters mucin-type O-glycosylation, causing Wnt activation | Colorectal | [87] |

| GALNT10 | Suppressive | Cell surface glycoproteome remodeling, preventing EMT and migration | Ovarian | [90] |

| GALNT14 | Oncogenic | Enhances β-catenin glycosylation, causing Wnt activation | Lung | [78] |

| Primary Cancer | GALNT Expression Pattern | Prognostic Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast (BRCA) | High GALNT6, -T13, -T14 in advanced disease. |

| [28,88,93,94] |

| Colon | Low GALNT3, -T4, -T6, -T12 in advanced disease. |

| [95,96,97,98] |

| Gastric | GALNT3, -T5, -T6, -T10 have varying impacts on outcomes |

| [99,100,101,102] |

| Pancreatic | GALNT3, -T5, -T6 have varying impacts on outcomes |

| [103,104,105] |

| Thyroid | High GALNT3 expression in poor prognosis. |

| [106] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Iyer, S.C.; Srinivasan, D.K.; Parameswaran, R. GalNAc-Transferases in Cancer. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010005

Iyer SC, Srinivasan DK, Parameswaran R. GalNAc-Transferases in Cancer. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleIyer, Shruthi C., Dinesh Kumar Srinivasan, and Rajeev Parameswaran. 2026. "GalNAc-Transferases in Cancer" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010005

APA StyleIyer, S. C., Srinivasan, D. K., & Parameswaran, R. (2026). GalNAc-Transferases in Cancer. Biomedicines, 14(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010005