Psychological Profiles in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Distinct Emotional and Behavioral Patterns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Design

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Data and Code Availability Statement

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Sociodemographic Data and Clinical Data

3.2. Personality Characteristics of UC and CD Patients

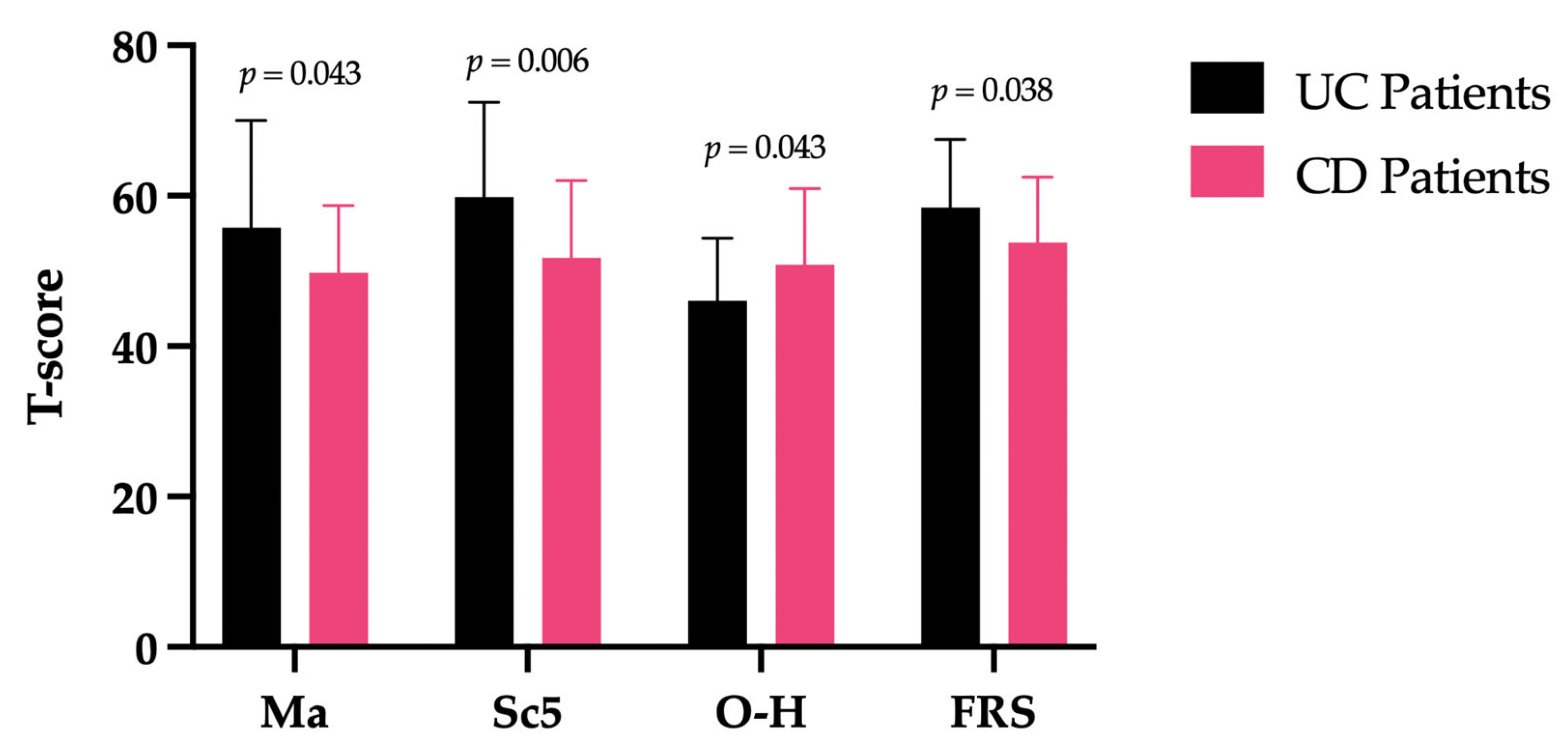

3.3. Differences Between UC and CD Patients in the MMPI-2 Scales Scores

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogler, G.; Singh, A.; Kavanaugh, A.; Rubin, D.T. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Concepts, Treatment, and Implications for Disease Management. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, S.R.; Keefer, L.; Wilding, H.; Hewitt, C.; Graff, L.A.; Mikocka-Walus, A. Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses—Part II. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuendorf, R.; Harding, A.; Stello, N.; Hanes, D.; Wahbeh, H. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aszalós, Z. Neurological and psychiatric aspects of some gastrointestinal diseases. Orvosi Hetil. 2008, 149, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, K.L. MMPI correlates of ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Psychol. 1970, 26, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, A.W.; Schmitt, P.; Patterson, J.F.; Rothman, E. Personality Differences Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients and Their Healthy Siblings. Psychosom. Med. 1973, 35, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, R.; Freyberger, H.; Zepf, S. Personality Features of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Psychother. Psychosom. 1977, 28, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathmann, P.; Linzmayer, L.; Grünberger, J. Contribution to the objective evaluation of the personality features of the colitis patient (author’s transl). Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 1981, 131, 421–425. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, H.; Minozzi, S.; Kopylov, U.; Verstockt, B.; Chaparro, M.; Buskens, C.; Warusavitarne, J.; Agrawal, M.; Allocca, M.; Atreya, R.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 1531–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbord, M.; Eliakim, R.; Bettenworth, D.; Karmiris, K.; Katsanos, K.; Kopylov, U.; Kucharzik, T.; Molnár, T.; Raine, T.; Sebastian, S.; et al. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2: Current Management. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2017, 11, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tontini, G.E.; Vecchi, M.; Pastorelli, L.; Neurath, M.F.; Neumann, H. Differential diagnosis in inflammatory bowel disease colitis: State of the art and future perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Mehandru, S.; Colombel, J.-F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2017, 389, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, S.; Fiocchi, C. Ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabéu Juan, P.; Cabezos Sirvent, P.; Sempere Robles, L.; van-der Hofstadt Gomis, A.; Rodríguez Marín, J.; van-der Hofstadt Román, C.J. Differences in the Quality of Life of Patients Recently Diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavani, P.; Ravella, B.; Patel, K.H.; Sikdar, N.; Kancherla, N.; Zahdeh, T.; Nerella, R. Management of Crohn’s Disease and Its Complexities: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e67499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumery, M.; Singh, S.; Dulai, P.S.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Sandborn, W.J. Natural History of Adult Ulcerative Colitis in Population-based Cohorts: A Systematic Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 343–356.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordi, S.B.U.; Lang, B.M.; Auschra, B.; von Känel, R.; Biedermann, L.; Greuter, T.; Schreiner, P.; Rogler, G.; Krupka, N.; Sulz, M.C.; et al. Depressive Symptoms Predict Clinical Recurrence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 28, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.N.; Graham, J.R.; Ben-Porath, Y.S. MMPI-2 (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2): Manual for Administration, Scoring, and Interpretation; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, J.N.; Williams, C.L.; Fowler, R.D. Fondamenti per L’interpretazione del MMPI-2 e del MMPI-A, 2nd ed.; Giunti OS Organizzazioni Speciali: Florence, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, J.D.; Chuai, S.; Nessel, L.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Aberra, F.N.; Ellenberg, J.H. Use of the noninvasive components of the mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, W.R. Predicting the Crohnʼs disease activity index from the harvey-bradshaw index. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2006, 12, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burisch, J. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Occurrence, course and prognosis during the first year of disease in a European population-based inception cohort. Dan. Med. J. 2014, 61, B4778. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Blanco, B.L.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Hernández, E.G. The influence of personality factors on health-related quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 62, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuffrida, E.; Mangia, M.; Lavagna, A.; Morello, E.; Cosimato, M.; Rocca, R.; Daperno, M. Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Prevention and Monitoring Strategies According with Risk Factors. Clin. Manag. Issues 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.J.; Bagby, R.M. New Trends in Alexithymia Research. Psychother. Psychosom. 2004, 73, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.; Naegeli, A.N.; Lukanova, R.; Shan, M.; Wild, R.; Hennessy, F.; Kommoju, U.J.; Bleakman, A.P.; Gibble, T.H. Rectal Urgency Among Patients with Ulcerative Colitis or Crohn’s Disease: Analyses from a Global Survey. Crohn’s Colitis 360 2023, 5, otad052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, C.; Sin, J.; Fear, N.T.; Chalder, T. A systematic review of the psychological correlates of adjustment outcomes in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 47, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Barbera, D.; Bonanno, B.; Rumeo, M.V.; Alabastro, V.; Frenda, M.; Massihnia, E.; Morgante, M.C.; Sideli, L.; Craxì, A.; Cappello, M.; et al. Alexithymia and personality traits of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabova, K.; Bednarikova, H.; Meier, Z.; Tavel, P. Exploring intimacy and family planning in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A qualitative study. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2401610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R. MMPI-2: Assessing Personality and Psychopathology, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hyphantis, T.; Antoniou, K.; Tomenson, B.; Tsianos, E.; Mavreas, V.; Creed, F. Is the personality characteristic “impulsive sensation seeking” correlated to differences in current smoking between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients? Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2010, 32, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horenstein, A.; Heimberg, R.G. Anxiety disorders and healthcare utilization: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 81, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, L.; Todd, J.; Scott, A.; Gatzounis, R.; Menzies, R.E.; Meulders, A. Safety behaviours or safety precautions? The role of subtle avoidance in anxiety disorders in the context of chronic physical illness. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 92, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrass, K.M.; Lovatt, J.; Barberio, B.; Yuan, Y.; Gracie, D.J.; Ford, A.C. Bidirectional brain–gut axis effects influence mood and prognosis in IBD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2022, 71, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroie, T.; Preda, C.; Istratescu, D.; Ciora, C.; Croitoru, A.; Diculescu, M. Anxiety and depression in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease: The role of fatigue and health-related quality of life. Medicine 2023, 102, e33713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaldaferri, F.; D’onofrio, A.M.; Chiera, E.; Gomez-Nguyen, A.; Ferrajoli, G.F.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Petito, V.; Laterza, L.; Pugliese, D.; Napolitano, D.; et al. Impact of Psychopathology and Gut Microbiota on Disease Progression in Ulcerative Colitis: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navabi, S.; Gorrepati, V.S.; Yadav, S.; Chintanaboina, J.; Maher, S.; Demuth, P.; Stern, B.; Stuart, A.; Tinsley, A.; Clarke, K.; et al. Influences and Impact of Anxiety and Depression in the Setting of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 2303–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrass, K.M.; Guthrie, E.A.; Black, C.J.; Selinger, C.P.; Gracie, D.J.; Ford, A.C. Characteristics and Effect of Anxiety and Depression Trajectories in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 118, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greywoode, R.; Ullman, T.; Keefer, L. National Prevalence of Psychological Distress and Use of Mental Health Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banovic, I.; Montreuil, L.; Derrey-Bunel, M.; Scrima, F.; Savoye, G.; Beaugerie, L.; Gay, M.-C. Toward Further Understanding of Crohn’s Disease-Related Fatigue: The Role of Depression and Emotional Processing. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, L.S.; Slaughter, J.C.; Horst, S.N.; Schwartz, D.A.; Beaulieu, D.B.; Haman, K.L.; Wang, L.; Martin, C.F.; Long, M.D.; Sandler, R.S.; et al. Association Between Affective-Cognitive Symptoms of Depression and Exacerbation of Crohn’s Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Raine, T.; Hendy, P.A.; Smith, P.J.; Limdi, J.K.; Hayee, B.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Parkes, G.C.; Selinger, C.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019, 68, s1–s106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UC Patients | CD Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 29 (44.61%) | 36 (55.39%) |

| Male/Female ratio | 21/8 (72.41–27.58%) | 17/19 (47.22–52.77%) |

| Mean age ± SD | 42.8 ± 15.2 | 43.7 ± 14.8 |

| Disease activity | Active = 14 (48.27%) Inactive = 12 (41.37%) In remission = 3 (10.34%) | Active = 23 (63.88%) Inactive = 8 (22.22%) In remission = 5 (13.88%) |

| Years of illness | Early-onset = 13 (44.82%) Late-onset = 16 (55.17%) | Early-onset = 16 (44.44%) Late-onset = 20 (55.55%) |

| Biological therapy | Yes = 14 (48.27%) No = 15 (51.72%) | Yes = 17 (47.22%) No = 19 (52.77%) |

| UC Patients (Mean Score + SD) | CD Patients (Mean Score + SD) | F(df) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma | 55.76 + 14.25 | 49.78 + 8.89 | 4.281(1) | 0.043 |

| Sc5 | 59.82 + 12.60 | 51.78 + 10.26 | 8.028(1) | 0.006 |

| O-H | 46.00 + 8.35 | 50.83 + 10.11 | 4.271(1) | 0.043 |

| FRS | 58.45 + 9.05 | 53.75 + 8.78 | 4.473(1) | 0.038 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Onofrio, A.M.; Maggio, E.; Milo, V.; Ferrajoli, G.F.; Ferrarese, D.; Chieffo, D.P.R.; Luciani, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Sani, G.; Scaldaferri, F.; et al. Psychological Profiles in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Distinct Emotional and Behavioral Patterns. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13071694

D’Onofrio AM, Maggio E, Milo V, Ferrajoli GF, Ferrarese D, Chieffo DPR, Luciani M, Gasbarrini A, Sani G, Scaldaferri F, et al. Psychological Profiles in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Distinct Emotional and Behavioral Patterns. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(7):1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13071694

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Onofrio, Antonio Maria, Eleonora Maggio, Valentina Milo, Gaspare Filippo Ferrajoli, Daniele Ferrarese, Daniela Pia Rosaria Chieffo, Massimiliano Luciani, Antonio Gasbarrini, Gabriele Sani, Franco Scaldaferri, and et al. 2025. "Psychological Profiles in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Distinct Emotional and Behavioral Patterns" Biomedicines 13, no. 7: 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13071694

APA StyleD’Onofrio, A. M., Maggio, E., Milo, V., Ferrajoli, G. F., Ferrarese, D., Chieffo, D. P. R., Luciani, M., Gasbarrini, A., Sani, G., Scaldaferri, F., Calia, R., & Camardese, G. (2025). Psychological Profiles in Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: Distinct Emotional and Behavioral Patterns. Biomedicines, 13(7), 1694. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13071694