Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Treatment of Neurosarcoidosis in Northern Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Outcome Variables

2.3. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

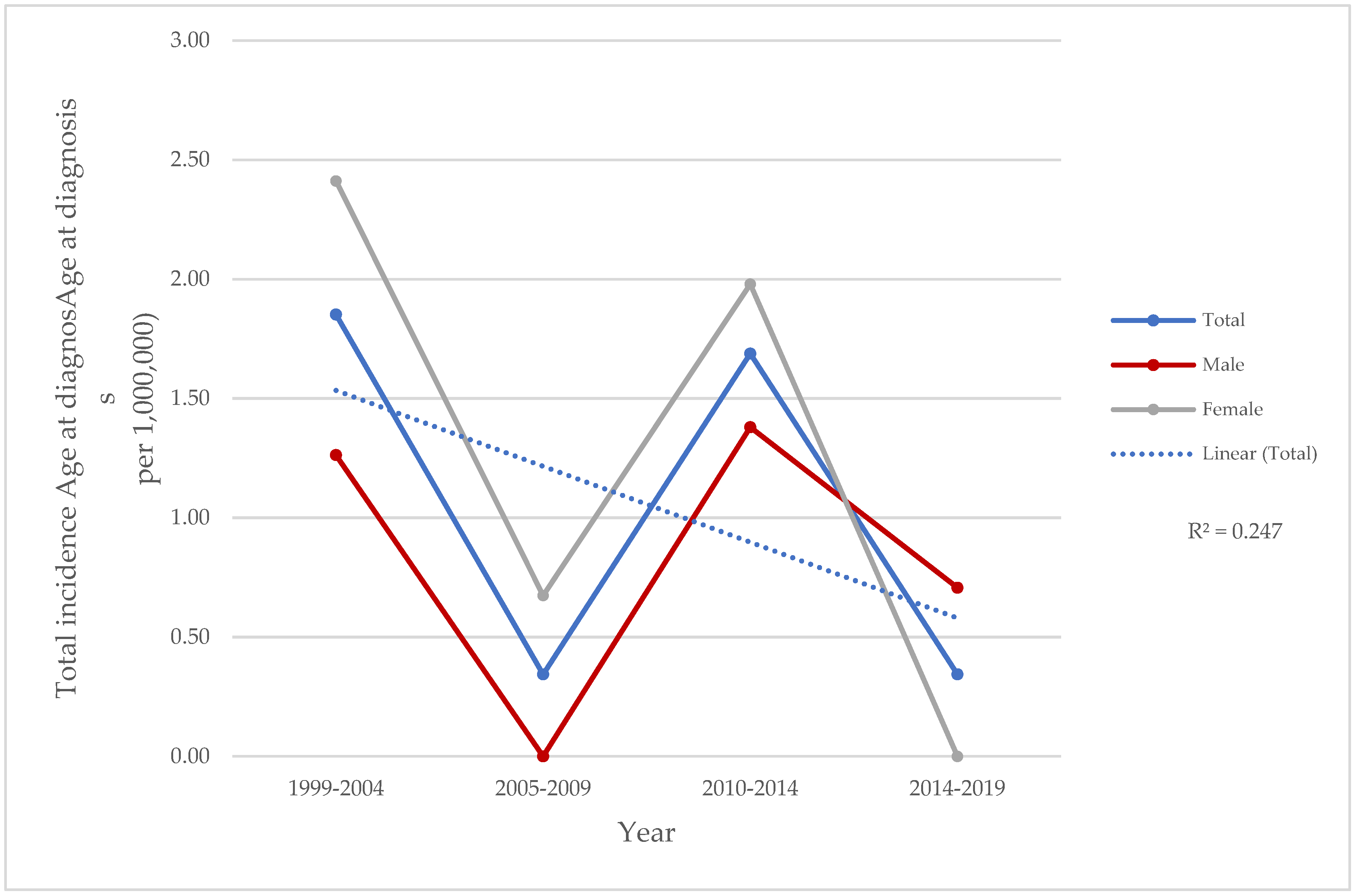

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Clinical Features at Baseline

3.3. Multisystemic Involvement

3.4. Biopsies, Imaging and Laboratory Findings

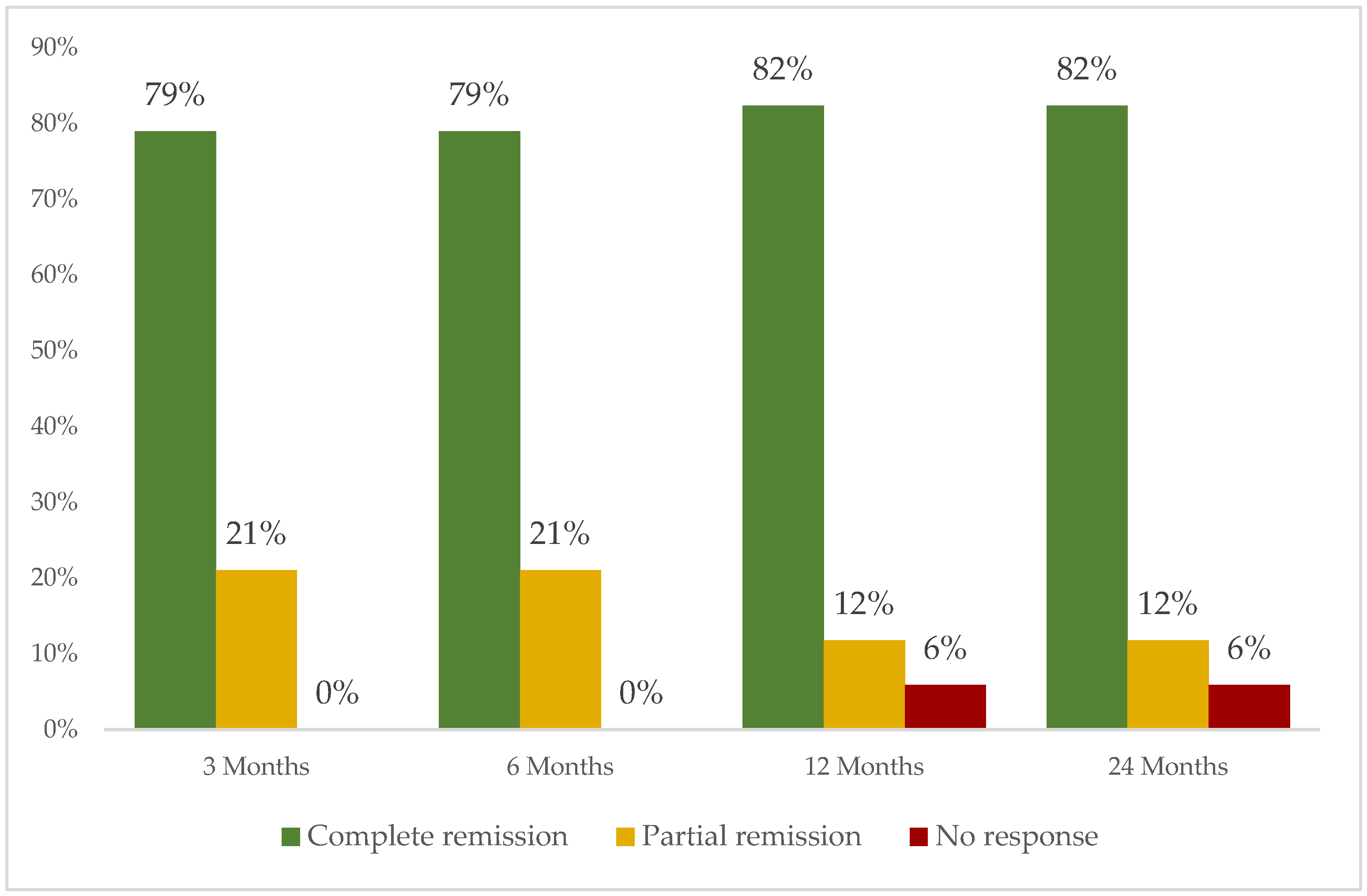

3.5. Treatment Administered

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ungprasert, P.; Matteson, E.L. Neurosarcoidosis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. 2017, 43, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valeyre, D.; Prasse, A.; Nunes, H.; Uzunhan, Y.; Brillet, P.-Y.; Müller-Quernheim, J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet 2014, 383, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ramón, R.; Gaitán-Valdizán, J.J.; Martín-Varillas, J.L.; Demetrio-Pablo, R.; Ferraz-Amaro, I.; Castañeda, S.; Blanco, R. Clinical Phenotypes of Sarcoidosis Using Cluster Analysis: A Spanish Population-Based Cohort Study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2024, 42, 2150–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Pawate, S.; Sparks, J.A. A Comprehenisve Guide to Immune Mediated Disorders of the Nervous System. In Neurorheumatology; Cho, T.A., Bhattacharyya, S., Helfgott, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Neurosarcoidosis; pp. 73–85. ISBN 978-3-030-16928-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sambon, P.; Sellimi, A.; Kozyreff, A.; Gheysens, O.; Pothen, L.; Yildiz, H.; van Pesch, V. Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Treatment, and Outcome of Neurosarcoidosis: A Mono-Centric Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 970168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, T.; Palace, J. Effects of Immunotherapies and Clinical Outcomes in Neurosarcoidosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 2466–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, D.; van de Beek, D.; Brouwer, M.C. Clinical Features, Treatment and Outcome in Neurosarcoidosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Neurol. 2016, 16, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namsrai, T.; Phillips, C.; Desborough, J.; Gregory, D.; Kelly, E.; Cook, M.; Parkinson, A. Diagnostic Delay of Sarcoidosis: Protocol for an Integrated Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0269762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Pawate, S.; Koth, L.L.; Cho, T.A.; Gelfand, J.M. Neurosarcoidosis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 8, e1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabel, U.; Hunninghake, G.W. ATS/ERS/WASOG Statement on Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Eur. Respir. J. 1995, 14, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B.J.; Royal, W.; Gelfand, J.M.; Clifford, D.B.; Tavee, J.; Pawate, S.; Berger, J.R.; Aksamit, A.J.; Krumholz, A.; Pardo, C.A.; et al. Definition and Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Neurosarcoidosis: From the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkema, E.V.; Cozier, Y.C. Sarcoidosis Epidemiology: Recent Estimates of Incidence, Prevalence and Risk Factors. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreras, P.; Stern, B.J. Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Neurosarcoidosis—Review Article. J. Neuroimmunol. 2022, 368, 577871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosselin, J.; Roy-Hewitson, C.; Bullis, S.S.M.; DeWitt, J.C.; Soares, B.P.; Dasari, S.; Nevares, A. Neurosarcoidosis: Phenotypes, Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2022, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungprasert, P.; Sukpornchairak, P.; Moss, B.P.; Ribeiro Neto, M.L.; Culver, D.A. Neurosarcoidosis: An Update on Diagnosis and Therapy. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2022, 22, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nozaki, K.; Judson, M.A. Neurosarcoidosis: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis and Treatment. Presse Med. 2012, 41, e331–e348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savale, L.; Huitema, M.; Shlobin, O.; Kouranos, V.; Nathan, S.D.; Nunes, H.; Gupta, R.; Grutters, J.C.; Culver, D.A.; Post, M.C.; et al. WASOG Statement on the Diagnosis and Management of Sarcoidosis-Associated Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022, 31, 210165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, M.A.; Baughman, R.P.; Costabel, U.; Flavin, S.; Lo, K.H.; Kavuru, M.S.; Drent, M. Efficacy of Infliximab in Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis: Results from a Randomised Trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen Aubart, F.; Bouvry, D.; Galanaud, D.; Dehais, C.; Mathey, G.; Psimaras, D.; Haroche, J.; Pottier, C.; Hie, M.; Mathian, A.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Refractory Neurosarcoidosis Treated with Infliximab. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ramón, R.; Gaitán-Valdizán, J.J.; Sánchez-Bilbao, L.; Martín-Varillas, J.L.; Martínez-López, D.; Demetrio-Pablo, R.; González-Vela, M.C.; Cifrián, J.; Castañeda, S.; Llorca, J.; et al. Epidemiology of Sarcoidosis in Northern Spain, 1999–2019: A Population-Based Study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 91, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd Edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascón-Bayarri, J.; Mañá, J.; Martínez-Yélamos, S.; Murillo, O.; Reñé, R.; Rubio, F. Neurosarcoidosis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 22, e125–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonhard, S.E.; Fritz, D.; Eftimov, F.; van der Kooi, A.J.; van de Beek, D.; Brouwer, M.C. Neurosarcoidosis in a Tertiary Referral Center: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study. Medicine 2016, 95, e3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, B.; Chapelon-Abric, C.; Biard, L.; Saadoun, D.; Demeret, S.; Dormont, D.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Cacoub, P. Association of Prognostic Factors and Immunosuppressive Treatment With Long-Term Outcomes in Neurosarcoidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, J.; Anadure, R.; Gupta, S.; Wilson, V.; Saxena, R.; Sahu, S.; Mutreja, D. A Study of the Clinical Profile, Radiologic Features, and Therapeutic Outcomes in Neurosarcoidosis from Two Tertiary Care Centers in Southern India. Neurol. India 2020, 68, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byg, K.-E.; Illes, Z.; Sejbaek, T.; Nguyen, N.; Möller, S.; Lambertsen, K.L.; Nielsen, H.H.; Ellingsen, T. A Prospective, One-Year Follow-up Study of Patients Newly Diagnosed with Neurosarcoidosis. J. Neuroimmunol. 2022, 369, 577913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorman, J.; Warrior, L.; Pandya, V.; Sun, Y.; Ninan, J.; Trick, W.; Zhang, H.; Ouyang, B. Neurosarcoidosis in a Public Safety Net Hospital: A Study of 82 Cases. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2019, 36, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affan, M.; Mahajan, A.; Rehman, T.; Kananeh, M.; Schultz, L.; Cerghet, M. The Effect of Race on Clinical Presentation and Outcomes in Neurosarcoidosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 417, 117073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voortman, M.; Fritz, D.; Vogels, O.J.M.; Van De Beek, D.; De Vries, J.; Brouwer, M.C.; Drent, M. Clinical Manifestations of Neurosarcoidosis in the Netherlands. J. Neurol. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, R.P.; Teirstein, A.S.; Judson, M.A.; Rossman, M.D.; Yeager, H.J.; Bresnitz, E.A.; DePalo, L.; Hunninghake, G.; Iannuzzi, M.C.; Johns, C.J.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Patients in a Case Control Study of Sarcoidosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 1885–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Sellarés, J.; Bosch, X.; Hernández, F.; Kostov, B.; Sisó-Almirall, A.; Casany, C.L.; Santos, J.M.; Paradela, M.; Sanchez, M.; et al. Epidemiologic Patterns of Disease Expression in Sarcoidosis: Age, Gender and Ethnicity-Related Differences. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2016, 34, 380–388. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, A.D.; Rifkin, L.M. Sarcoidosis: Sex-Dependent Variations in Presentation and Management. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 2014, 236905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebel, R.; Dubaniewicz-Wybieralska, M.; Dubaniewicz, A. Overview of Neurosarcoidosis: Recent Advances. J. Neurol. 2015, 262, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, J.; Paz Soldan, M.M.; Galli, J.; Salzman, K.L.; Kresser, J.; Bacharach, R.; DeWitt, L.D.; Klein, J.; Rose, J.; Greenlee, J.; et al. Neurosarcoidosis: Longitudinal Experience in a Single-Center, Academic Healthcare System. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelfand, J.M.; Bradshaw, M.J.; Stern, B.J.; Clifford, D.B.; Wang, Y.; Cho, T.A.; Koth, L.L.; Hauser, S.L.; Dierkhising, J.; Vu, N.; et al. Infliximab for the Treatment of CNS Sarcoidosis: A Multi-Institutional Series. Neurology 2017, 89, 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.; Hospital, M.G.; Barreras, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Hospital, W.; Hutto, S. Consensus Recommendations for the Management of Neurosarcoidosis A Delphi Survey of Experts Across the United States. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, e200429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ramón, R.; Gaitán-Valdizán, J.J.; González-Mazón, I.; Sánchez-Bilbao, L.; Martín-Varillas, J.L.; Martínez-López, D.; Demetrio-Pablo, R.; González-Vela, M.C.; Ferraz-Amaro, I.; Castañeda, S.; et al. Systemic Treatment in Sarcoidosis: Experience over Two Decades. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 108, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Characteristics | Total (n = 29) | Female (n = 18) | Male (n = 11) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic parameters | ||||

| 42.3 ± 15.1 11.9 ± 6.6 27 (93.1) 2 (6.9) 7 (24.1) | 46 ± 16.1 11.5 ± 6.1 16 (88.9) 2 (11.1) 2 (11.1) | 35.7 ± 12.2 12.5 ± 7.7 11 (100) 0 5 (45.5) | 0.350 0.174 0.265 0.265 0.023 |

| Non-neurological systemic involvement, n (%) | 27 (96.6) | 18 (100) | 9 (81.1) | 0.054 |

| 22 (75.9) 15 (51.7) 12 (41.4) 10 (34.5) 4 (13.8) | 15 (83.3) 11 (61.1) 7 (38.9) 7 (38.9) 3 (16.7) | 7 (54.5) 4 (36.4) 5 (26.3) 3 (27.3) 1 (9.1) | 0.199 0.256 0.643 0.417 0.028 |

| Neurological involvement, n (%) | 29 (100) | 18 (100) | 11 (100) | 0.164 |

| 10 (34.5) 7 (24.1) 4 (13.8) 3 (10.3) 3 (10.3) 2 (6.9) | 6 (33.3) 2 (11.1) 4 (22.2) 3 (16.7) 2 (11.1) 1 (5.6) | 4 (36.4) 5 (45.5) 0 0 1 (9.1) 2 (18.2) | 0.979 0.029 0.102 0.165 0.900 0.685 |

| Laboratory findings, n (%) | ||||

| 22/25 (88) 5/23 (21.7) 1/26 (3.8) 1/24 (4.2) | 15/17 (81.2) 3/14 (21.4) 0 0 | 7/8 (87.5) 2/9 (22.2) 1/9 (11.1) 1/8 (12.5) | 0.958 0.808 0.197 0.149 |

| Biopsy, n (%) | 23/27 (85.2) | 14/17 (82.4) | 9/10 (90) | 0.629 |

| 10/23 (43.5) 3/23 (13) 10/23 (43.5) | 6/14 (42.9) 1/14 (7.1) 7/14 (50) | 4/9 (44.4) 2/9 (22.2) 3/9 (33.3) | 0.831 0.265 0.341 |

| Imaging, n (%) | ||||

| 23/27 (85.2) 23/26 (88.5) 16/25 (64) | 14/17 (82.4) 14/16 (87.5) 9/16 (56.3) | 9/10 (90) 9/10 (90) 6/9 (66.7) | 0.629 0.888 0.696 |

| NS Subtype | N (%) | Other Clinical Manifestations | Conventional Immunosuppressant, N = 22 | Monoclonal Anti-TNFα, N = 22 | ETN, N = 1 N (%) | TCZ, N = 1 N (%) | SCK, N = 1 N (%) | RTX N = 1 N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic headache | 10 (34.5) | Articular (n = 7, 70%) Lung (n = 6, 60%) Skin (n = 3, 30%) Ocular (n = 3, 30%) GI (n = 2, 20%) | MTX (n = 5, 50%) AZA (n = 1, 10%) | GLM (n = 1, 10%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (10) | 0) |

| Cranial neuropathy | 7 (24.1) | Lung (n = 5, 71.4%) Ocular (n = 5, 71.4%) Articular (n = 3, 42.9%) Skin (n = 3, 42.9%) GI (n = 1, 14.3%) | MTX (n = 5, 71.4%) AZA (n = 5, 71.4%) | IFX (n = 3, 42.9%) ADA (n = 3, 42.9%) GLM (n = 1, 14.3%) | 1 (14.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myelitis | 4 (13.8) | Lung (n = 4, 100%) Ocular (n = 1, 25%) Skin (n = 1, 25%) Articular (n = 1, 25%) | MTX (n = 2, 50%) | IFX (n = 2, 50%) GLM (n = 1, 25%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 3 (10.3) | Lung (n = 3, 100%) Ocular (n = 1, 33.3%) Articular (n = 1, 33.3%) | MTX (n = 1, 33.3%) AZA (n = 1, 33.3%) | IFX (n = 1, 33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic headache and cranial neuropathy | 3 (10.3) | Lung (n = 3, 100%) Skin (n = 3, 100%) Articular (n = 3, 100%) Ocular (n = 2, 66.7%) GI (n = 1, 33.3%) | MTX (n = 2, 66.7%) | ADA (n = 2, 66.7%) IFX (n = 1, 33.3%) | 0 | 0) | 0 | 1 (33.3) |

| Aseptic meningitis | 2 (6.9) | Lung (n = 1, 50%) | MTX (n = 1, 50%) | IFX (n = 1, 50%) ADA (n = 1, 50%) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 | 0 |

| Total (n = 29) | 29 (100) | Lung (n = 22, 75.9%) Articular (n = 15, 51.7%) Ocular (n = 12, 41.4%) Skin (n = 10, 34.5%) GI (n = 4, 13.8%) | MTX (n = 15, 51.7%) AZA (n = 7, 24.1%) | IFX (n = 8, 27.6%) ADA (n = 6, 20.7%) GLM (n = 3, 10.3%) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.4) |

| Author, Year | Country | Cases | Male, N (%) | Age at Onset Years, Mean ± SD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | NS | % | S | NS | S | NS | ||

| Gascón-Bayarri et al., 2011 [22] | Spain | 445 | 30 | 6.7 | ND | 10 (33.4) | ND | 48.3 ± ND |

| Leonhard et al., 2016 [23] | The Netherlands | ND | 52 | ND | ND | 22 (48.0) | 44 ± ND | 43.0 ± ND |

| Joubert et al., 2017 [24] | France | 690 | 234 | 33.9 | ND | 117 (50) | ND | 31.5 ± ND |

| Dorman et al., 2019 [27] | USA | 1706 | 82 | 4.8 | 691 (40.6) | 43 (52.4) | 49 ± 10.8 | 45.0 ± 11.4 |

| Arun et al., 2020 [6] | UK | ND | 80 | ND | ND | 35 (44) | ND | 47.8 ± ND |

| Goel et al., 2020 [25] | India | ND | 12 | ND | ND | 4 (33.4) | ND | 44.0 ± 9.2 |

| Sambon et al., 2022 [5] | Belgium | 180 | 22 | 12.2 | ND | 14 (64) | ND | 40.5 ± ND |

| Byg et al., 2022 [26] | Denmark | ND | 20 | ND | ND | 11 (55) | ND | 51.6 ± ND |

| Present study, 2025 | Spain | 342 | 29 | 8.5 | 165 (48.2) | 11 (37.9) | 47.7 ± 15.1 | 42.3 ± 15.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrero-Morant, A.; Fernández-Ramón, R.; Prieto-Peña, D.; Martín-Varillas, J.L.; Castañeda, S.; Blanco, R. Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Treatment of Neurosarcoidosis in Northern Spain. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061360

Herrero-Morant A, Fernández-Ramón R, Prieto-Peña D, Martín-Varillas JL, Castañeda S, Blanco R. Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Treatment of Neurosarcoidosis in Northern Spain. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(6):1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061360

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrero-Morant, Alba, Raúl Fernández-Ramón, Diana Prieto-Peña, José Luis Martín-Varillas, Santos Castañeda, and Ricardo Blanco. 2025. "Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Treatment of Neurosarcoidosis in Northern Spain" Biomedicines 13, no. 6: 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061360

APA StyleHerrero-Morant, A., Fernández-Ramón, R., Prieto-Peña, D., Martín-Varillas, J. L., Castañeda, S., & Blanco, R. (2025). Epidemiology, Clinical Features and Treatment of Neurosarcoidosis in Northern Spain. Biomedicines, 13(6), 1360. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061360