Abstract

Background/Objective: Prostate cancer (PCa) represents the second-most common cancer among men worldwide. Obesity is generally considered as a risk factor for cancer and it has been associated with a 20–30% increased risk of PCa death. The present systematic review and meta-analyses aimed to highlight any existing trends between prostate neoplasm stages according to normal weight, overweight and obesity conditions. Methods: All interventional records such as randomized clinical trials, quasi-experimental studies and observational studies were included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis which reported PCa stages according to Gleason (GS) or TNM scores according to the BMI-related incidence, as normal weight, overweight and obesity groups. Results: Twenty-nine studies were included in the present study. As regards the GS scoring system, 1.09% of high grade in GS was reported among PCa normal weights. Among PCa overweights, 0.98% of low grade was registered in GS. The same trend was recorded among obese PCa patients, since 0.79% of low grade in GS was also registered. As regards TNM scores, both normal weight, overweight and obese PCa patients registered a significant incidence in non-advanced TNM score, without any significant differences considering higher TNM assessments. Conclusions: Although the literature seemed to be more in favor of associations between BMI and GS, no specific mechanisms were highlighted between obesity and PCa progression. In this regard, the low androgen microenvironment in obese men could play an important role, but further studies will be necessary in this direction.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents the second most frequent cancer and the fifth cause of death among men all around the world, encountering more than 1,460,000 estimated cases and 396,000 deaths in 2022 [1], until 2040 encountering around 2.4 million cases and 712,000 deaths, also due to aging and increasing worldwide population [2]. In Italy, prostate cancer is the most frequent malignancy in men (19.8% of all cancers in men), with an estimated 41,100 new diagnoses in 2023 and an estimated 8200 deaths in 2022. Its incidence increases with advancing age, predominantly affecting males after age 50 with a peak incidence around age 70. The prognosis of this cancer depends on a number of factors and, in particular, on the extent of the neoplasm at the time of diagnosis and the age of the patient [3]. Thanks to surgery improvements and treatment approaches, PCa patients have ameliorated both their duration and quality of life [4,5].

Obesity has been associated with a 20–30% increased risk of PCa death [6]. However, there is very little evidence suggesting a linkage between body mass index (BMI) and PCa [7,8]. Conversely, further evidence suggests an increased risk of PCa or death among patients with a high BMI [9,10].

PCa diagnosis is performed thanks to prostate biopsy and histology, which give important biochemical characteristics of the disease. The Gleason system (GS) represents a histologic scoring system for PCa through structural characteristics [11]. In GS, histologic features defined as grades are recognized, which vary from GS grade 1, indicating the well-differentiated with the best prognosis to GS grade 5, indicating the grimmest prognosis [11,12]. The GS score varies from 2 to 10 and indicates the level of aggressiveness of PCa [11,12,13].

Another cancer scoring system is the TNM classification, which suggests prompt information on cancer extension for its general control [14]. The TNM system aims to control and surveil the cancer [9], helping clinicians in their clinical care and decision making [9]. Evidence suggested that obesity is linked to the frequency of cancers, unfortunate treatment goals and elevated death rates [15,16]. Especially, obesity has been suggested to have a positive and direct correlation with the PCa aggressiveness with also higher GS scores [17,18,19]. Greater BMI values supply a more advantageous microenvironment for PCa onset and development, which embrace dysfunctions in the endocrine system, such as testosterone, estrogen and insulin-like growth factor-I serum levels [20,21]. Particularly, PCa interferes with adipose metabolism and testosterone, highlighting a mutual relationship between periprostatic adipose tissue and cancers [22]. PCa also modulates the leptin secretion linked to the quality of periglandular adipose tissue [23]. Adipocytes and PCa cells are also associated with paracrine cytokines inducing lipolysis in adipocytes and enhancing free fatty acids secretion [24].

Dyslipidemia and saturated fatty acids assumptions seem to be associated with an increased recurrence and risk of death in PCa men [25,26] and are involved in producing numerous elements that enhance PCa cell proliferation and disease advancement, embracing extracellular vesicles [27], pro-inflammatory cytokines [28] and other adipokines [29]. Obesity directly modifies cytokines secretion in adipocytes, impacting cancer growth and progression and enhancing tumor survival [30].

The present systematic review and meta-analyses aimed to highlight any existing trends between prostate neoplasm stages according to normal weight, overweight and obesity conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Research

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out thanks to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) [31]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO no. CRD42024580302. Keywords were searched through the MeSH terminology and mixed thanks to Boolean operators (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strings carried out to perform this systematic and meta-analysis study.

Additionally, a research question was formulated using the PIO methodology (Table 2).

Table 2.

The PIO tool for the present systematic review and meta-analysis.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To include a more extensive number of studies, we included all interventional records of specifically randomized clinical trials, quasi-experimental studies and also observational ones. All the selected studies reported PCa stages according to Gleason or TNM scores according to the BMI-related incidence, as normal weight, overweight and obesity groups. Thus, only frequencies and percentages in BMI-related groups according to the PCa stages were collected. Finally, all records written in English language and available in their full text versions were included. On the other hand, records including pediatric patients or healthy participants were excluded for further analysis.

2.3. Manuscripts Selection

At the beginning, articles were recognized thanks to systematic research in Embase, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases and a reference management software uploaded full-text versions and removed duplicates. Two independent reviewers (E.V. and A.R.) read the title and abstract of the selected manuscripts, and those which were classified as unsuitable were removed for further readings. Then, screened records were uploaded and assessed more deeply for their potential eligibility. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved clarifying any doubts and reaching consensus. If the disagreement persisted, another reviewer was consulted (K.H.) and a final decision was reached. Data were extracted including study characteristics, as author, year of publication, aim, design, sample size, cancer stage and incidence of PCa stages according to patients’ BMI conditions.

2.4. Selected Records

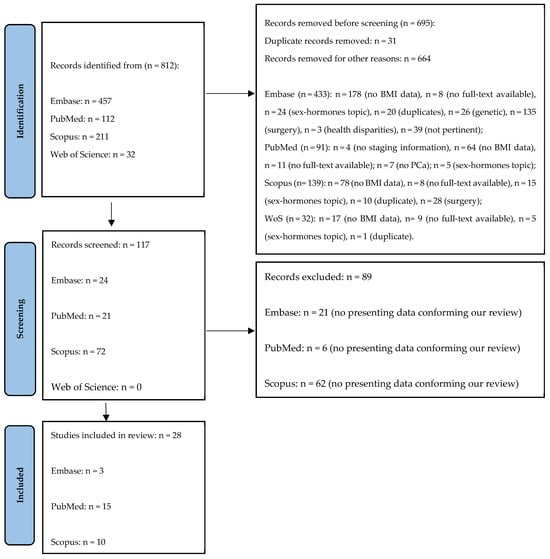

A total of 812 records were identified, specifically 457 from Embase, 112 from PubMed, 211 from Scopus and 32 from Web of Science. Of these, 695 records were removed, as 31 were duplicates and 664 were excluded for other reasons, as shown in Figure 1. From the remaining 111 records, a further 88 were excluded and a total of 29 records were finally included in the present study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Prisma flow diagram.

2.5. Interventions and Outcomes

The systematic review and meta-analysis included all studies among prostatic cancer patients both assessing the incidence of cases of prostate cancer and its relating staging according to Gleason and TNM score, among normal weight, overweight and obese patients.

Staging was based on the metastases at the tumor node (TNM) classification representing a scoring tool in PCa according to its extension. Specifically, in the initial stage, at the precancerous stage, the tumor was classified at stage T1 and progressively to the T2 stage, in which cancer cells started to rapidly grow and differentiate in tumor forms until reaching stages T3 and T4, in which cancer cells spread to the PCa microenvironments in their tissues and lymph nodes [32]. In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, we gathered the first and the second stage of TNM in the non-advanced stage and the third and the fourth stage of TNM in the advanced stage. Gleason score was assessed thanks to the International Society of Urological Pathology modified Gleason grading system that recommended this scoring system [33], which corresponded well with patient prognosis, and it seemed to be very easy to use in clinical practice [33]. Substantially, a Gleason score less than 6 was associated with a low grade of PCa and a Gleason score more than 7 was associated with high-grade prostate cancer [34]. Finally, body mass index (BMI) was assessed as body weight divided by the square of the height (kg/m2) and it was grouped into three main groups, as normal weight (BMI ≤ 24.99), overweight (25.00 ≤ BMI ≥ 29.99) and obese (BMI ≥ 30.00) groups according to the classification of obesity of the World Health Organization [35].

2.6. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

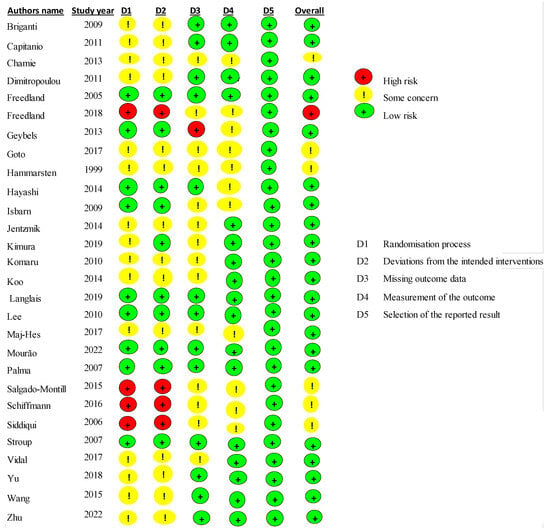

Publication bias was evaluated thanks to the risk bias tool which displayed bias risk assessments as well as underlying bias due to the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data and in their related assessments and bias in selection of the reporting approaches [36] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary of the included studies [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

For each study included in the present review, the authors compared their judgements and then reached these assessments. Overall, the given agreements had low risk for most of the included studies (only 5 out 29 studies had some item of high risk).

2.7. Data Analysis

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess the risk of prostate cancer among normal weight, overweight and obese patients. The body weight was categories-based BMI scores, whereas TNM and Gleason grading were performed as low and high grades. The retrieved data from the original studies were manually entered into Microsoft Excel. Heterogeneity among studies was analyzed using the chi-square test (χ2) with 95% (p < 0.05) and magnitude of heterogenicity between studies was determined using the I2 test values and categorized as high (>75%), medium (50–75%) and low (<50%) heterogeneity. To balance the observed heterogenicity, we employed the random effects model. The effect size for the dichotomous variable was expressed as relative risk, also known as risk ratio, with 95% confidence interval (CI). The pooled data were analyzed using RevMan (Version 5.4. Copenhagen: the Cochrane Collaboration, 2020).

3. Results

3.1. Selected Studies

Twenty-nine studies were included in the present study as meeting the above-mentioned inclusion criteria [34,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. Table 3 shows all the main characteristics for each study included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis, specifically study design and PCa assessment, whether it included GS or TNM or both, the aim of the study, the sample size and the achieved findings.

Table 3.

The main characteristics of the studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis (n = 29).

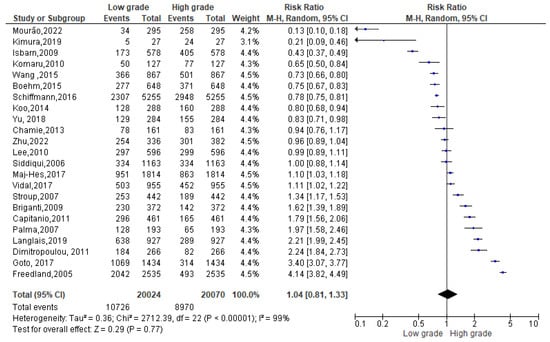

3.2. Meta-Analysis According to Gleason Scores

A total of 57,554 events were registered. Of these, 19,460 reported a normal weight condition, 11,389 an overweight one and 26,705 an obese condition. Among normal weight events reported (Figure 3), 10,791 events belonged to a Gleason low-grade score and 8669 to a Gleason high-grade one. Since the Cochrane Q test showed high heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.36 and Chi2 = 2712.39 with I2 = 99%), PCa patients recording a normal weight condition also registered 1.04% of high grade in Gleason score, at 95% confidence intervals [1.04 (0.81,1.33) p = 0.00] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Gleason scores in normal weight PCa patients [34,37,38,39,40,42,44,47,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

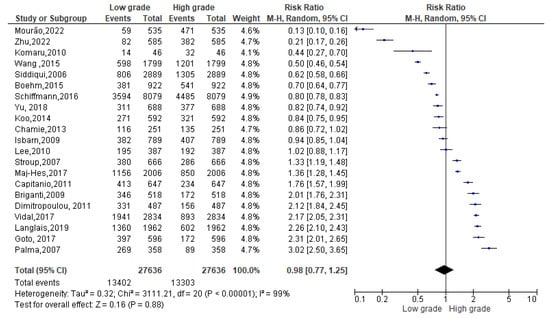

Among 26,705 overweight events reported (Figure 4), 13,402 events belonged to a Gleason low-grade score and 13,303 to a Gleason high-grade one. Since the Cochrane Q test showed high heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.32 and Chi2 = 3111.21 with I2 = 99%), PCa patients recording an overweight condition, conversely, registered 0.98% of low-grade Gleason score rather than a high one [0.98 (0.77,1.25), p = 0.00] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Gleason scores in overweight PCa patients [34,37,38,39,40,44,47,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

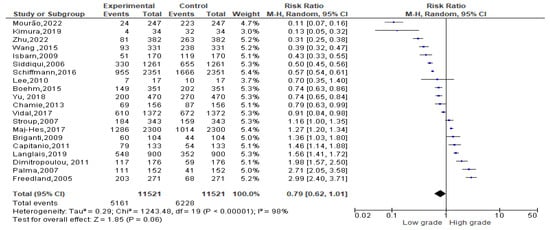

Among 11,389 obese events recorded, 5161 events belonged to a low-grade Gleason score and 6228 to a high-grade Gleason score. Since the Cochrane Q test showed high heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.29 and Chi2 = 1243.48 with I2 = 98%), PCa patients recording an obesity condition registered 0.79% of low-grade Gleason score rather than a high one [0.79 (0.62, 1.01), p = 0.00] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Gleason scores in obese PCa patients [34,37,38,39,40,41,47,50,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

3.3. Meta-Analysis According to TNM Scores

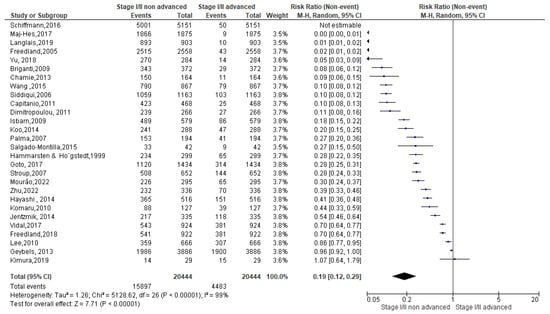

A total of 61,202 events were registered. Of these, 20,444 reported a normal weight condition, 28,285 an overweight one and 12,473 an obese condition. Among normal weight events recorded (Figure 6), 15,897 events belonged to non-advanced TNM score and 4483 to advanced TNM score. Since the Cochrane Q test showed high heterogeneity (Tau2 = 1.26 and Chi2 = 5128.62 with I2 = 99%), PCa patients recording normal weight condition registered a significant incidence in non-advanced TNM score in their PCa conditions [0.19 (0.12, 0.29), p = 0.00] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

TNM scores in normal weight PCa patients [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

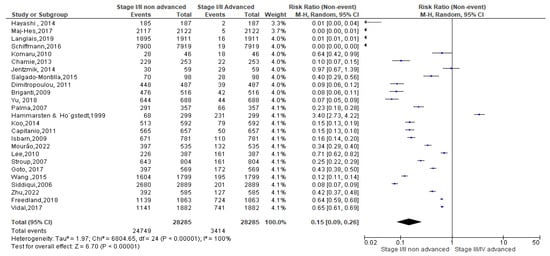

As regards the overweight condition, a total of 28,285 events were registered. Of these, 24,749 events belonged to non-advanced TNM score and 3414 to advanced TNM score. Since the Cochrane Q test showed high heterogeneity (Tau2 = 1.97 and Chi2 = 6804.65 with I2 = 100%), overweight PCa patients registered a significant incidence in non-advanced TNM score in their PCa conditions [0.15(0.09, 0.26), p = 0.00] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

TNM scores in overweight PCa patients [37,38,39,40,42,44,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

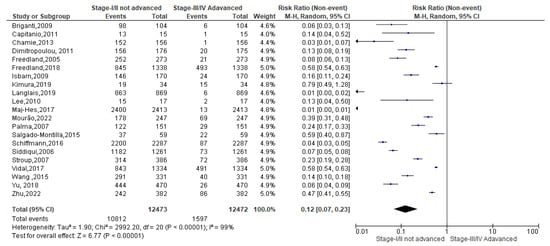

Finally, as regards the obese condition, a total of 12,473 events were registered. Of these, 10,812 events belonged to non-advanced TNM score and 1597 to advanced TNM score. Since the Cochrane Q test showed high heterogeneity (Tau2 = 1.90 and Chi2 = 2992.20 with I2 = 99%), obese PCa patients registered a significant incidence in non-advanced TNM score in their PCa conditions [0.19 (0.07, 0.23), p = 0.00] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

TNM scores in obese PCa patients [37,38,39,40,41,42,47,49,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

4. Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analyses aimed to highlight any existing trends between prostate neoplasm stages according to normal weight, overweight and obesity conditions. As regards the GS scoring system, 1.09% of high-grade GS was reported among PCa normal weights. Conversely, among PCa with overweight, it was 0.98% of low-grade GS was registered. The same trend was recorded among obese PCa patients, since 0.79% of low-grade GS was also registered. In this regard, evidence confirmed the same trend between BMI scores and GS ones, as a direct association was observed between BMI and the GS scores, specifically between higher BMI values and higher GS ones and also between normal BMI scores and low GS ones. These trends were comparable to data reported by Gioia et al. [65] among Caucasian men, and Liang et al. [5] in a cohort study assessing Selenium and Vitamin E for PCa prevention (SELECT), suggesting a relationship between higher BMI values and higher PCa grade risks, more specifically among men with a PCa family history. Obesity was also suggested as a likely risk factor for aggressive PCa and tumor recurrence [11] and race and high BMI were considered as independent of PCa’s high grade. These findings were also confirmed among Americans [11], wherein 72.4% of the patients with higher GS values were associated with higher BMI values, as also suggested by Zhou et al. [12] and by Kryvenko et al. [13], in which nearly 5118 PCa patients recorded higher GS values and also higher BMI ones. Additionally, Amling et al. [15] explained the impact of obesity on men undergoing radical prostatectomy, who reported the BMI variable as independent from GS scores and biochemical recurrence. Additional studies agreed to associate higher BMI values to worse prostate biopsy [1,11], while no associations were reported between obesity and PCa among European men [47,65].

In this regard, the PCa risk associated with higher BMI values might depend on different countries of origin and there was a lack of available evidence to consider the relationship between BMI and PCa growth and progression [16]. On the other hand, further evidence suggested that BMI was not associated with a raised risk of PCa at biopsy [66]. However, these results needed to be confirmed with additional studies among comparable populations also considering additional elements, such as the patient’s behaviors and serum hormone levels, especially in testosterone linked to obesity, which could favor the growth and progression of PCa aggressiveness [21]. As regards TNM scores, both normal weight, overweight and obese PCa patients registered a significant incidence in non-advanced TNM score, without any significant differences considering higher TNM assessments (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). However, the literature showed discordant evidence in this aspect, as Harrison et al. [22] observed no associations between BMI and PCa risk, which seemed to be in contrast to our present findings. However, Cao and Ma [24] underlined high heterogeneity among the reviewed studies and additional stratification of their data suggested a positive association between BMI and PCa mortality rates. These findings were consistent with those reported in another meta-analysis [19], which highlighted an inverse association between higher BMI scores and localized PCa and a positive association between higher BMI scores and advanced PCa. Thus, obese PCa men seemed to be more likely to develop an aggressive PCa with also a high tumor volume. Additionally, obese PCa men reported a significantly higher risk of disease recurrence, as well as an increase in mortality rate compared to normal weight PCa men [24]. On the other hand, previous analyses have suggested that obesity may not significantly influence the risk or aggressiveness of PCa, or that the association could depend on other factors, like hormonal status, race and timing of diagnosis [67]. Obese patients, although not presenting with more extensive disease initially, could have more aggressive histologic tumors. Thus, obesity could be considered a risk factor for high-grade tumors, even if not for greater local extension [68]. In this regard, the low androgen microenvironment in obese men could play an important role, but further studies will be necessary in this direction [28,29,30].

Eating lifestyles played a pivotal role in PCa biology and its related etiopathogenesis, on both the growth and progression of PCa. On the other hand, numerous nutrients and herbs played a promising role in decelerating PCa progression and decreasing the risk of morbidity and mortality, also adding benefits for the cardiovascular system, bone health and for the prevention of other cancers [69].

However, no specific mechanisms were highlighted between obesity and PCa progression [48], despite hyperinsulinemia, higher levels of growth factors, inflammation and its related cytokines and chemokines, alterations in steroid hormones and adiponectin levels and other factors (dysfunctions in microbiome, angiogenesis) have been mentioned [70,71]. In the obesity condition, especially in abdominal obesity, an increase in white adipose tissue (WAT) has been highlighted and several studies supported the linkage between PCa progression in the excessive presence of WAT [72,73]. Additionally, increased WAT concentrations could boost a latent chronic inflammation condition, known as an inducing role in the obesity–cancer relationship [74], also due to the interaction with cancer cells inducing cancer associated with adipocytes and contributing to the development of aggressive PCa [75]. Hence, the present systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted important implications in BMI in PCa staging, while at the same time, had some limitations. First of all, data included several study designs and it could be helpful to have a major number of cases. However, this methodological choice could negatively impact the quality of evidence or the comparability of data, due to the very high heterogeneity among the included data and the lack of adjustment for potential confounding factors.

A limitation of this meta-analysis is the use of BMI alone as a proxy for overweight and obesity. Although BMI is a valuable tool for population surveys and primary care screening, it has limitations when used as the sole tool for predicting chronic disease risk and assessing excess fat. BMI cut-off values should be reconsidered in populations of varying body build, age and/or ethnicity. Given that overweight individuals diagnosed by BMI are sometimes physically and physiologically fit by other measures, individuals overweight by, e.g., BMI should be more comprehensively assessed, diagnosed and monitored with anthropometric parameters relating to the amount of lean mass and fat mass adjusted for age, height and ethnicity. We have not evaluated the effect of being “underweight” on PCa prevalence; however, a meta-analysis including fewer studies (13 studies) reported that underweight PCa patients exhibited a tendency to present a decreased risk of PCa compared to those with normal weight; however, the effect was not statistically significant [76].

5. Conclusions

Obesity has been associated with a 20–30% increased risk of PCa death. The present systematic review and meta-analyses aimed to highlight any existing trends between prostate neoplasm stages (Gleason score, GS) according to normal weight, overweight and obesity conditions. As regards the GS scoring system, 1.09% of high-grade GS was reported among PCa normal weights. Among overweight PCa, a 0.98% of low-grade GS was registered. The same trend was recorded among obese PCa patients, since 0.79% of low-grade GS was also registered. Future studies, preferably prospective observational studies or patient-level pooled analyses, will investigate in greater depth the relationship between obesity and prostate cancer aggressiveness, ideally incorporating biological variables such as hormonal markers and inflammation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V.; methodology, K.H. and A.P.S.; software, K.H. and A.P.S.; validation, K.H. and A.P.S.; formal analysis, K.H. and A.P.S.; investigation, E.V., A.R., K.H. and A.P.S.; resources, O.C.; data curation, K.H. and A.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.V.; writing—review and editing, E.V.; visualization, O.C. and A.R.; supervision, O.C., F.M., M.S. and E.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from first co-authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors affiliated to the IRCCS Istituto Tumori “Giovanni Paolo II”, Bari are responsible for the views expressed in this article, which do not necessarily represent the Institute.

References

- Withrow, D.; Pilleron, S.; Nikita, N.; Ferlay, J.; Sharma, S.; Nicholson, B.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Lu-Yao, G. Current and projected number of years of life lost due to prostate cancer: A global study. Prostate 2022, 82, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute. Un Nuovo Approccio Dell’ue Allo Screening dei Tumori: Programmi di Diagnosi Precoce del Tumore Polmonare e Della Prostata. 2023. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/prevenzioneTumori/dettaglioContenutiPrevenzioneTumori.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=6151&area=prevenzioneTumori&menu=screening (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Guo, S.B.; Hu, L.S.; Huang, W.J.; Zhou, Z.Z.; Luo, H.Y.; Tian, X.P. Comparative investigation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy versus adjuvant immunotherapy in perioperative patients with cancer: A global-scale, cross-sectional, and large-sample informatics study. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 4660–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ketchum, N.S.; Goodman, P.J.; Klein, E.A.; Thompson, I.M., Jr. Is there a role for body mass index in the assessment of prostate cancer risk on biopsy? J. Urol. 2014, 192, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Calle, E.E.; Rodriguez, C.; Walker-Thurmond, K.; Thun, M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1625–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, A.G.; Goldbohm, R.A.; Dorant, E.; van den Brandt, P.A. Anthropometry in relation to prostate cancer risk in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atan, A. Metabesity and urological cancers. Turk J. Urol. 2017, 43, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Patel, A.V.; Calle, E.E.; Jacobs, E.J.; Chao, A.; Thun, M.J. Body mass index, height, and prostate cancer mortality in two large cohorts of adult men in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2001, 10, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci, E.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C. Height, body weight, and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1997, 6, 557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Freedland, S.J.; Bañez, L.L.; Sun, L.L.; Fitzsimons, N.J.; Moul, J.W. Obese men have higher-grade and larger tumors: An analysis of the duke prostate center database. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009, 12, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, X.; Pu, J.; Ouyang, J.; Li, G.; Ping, J.; Lu, Y.; Hou, J.; Han, Y. Correlation between body mass index (BMI) and the Gleason score of prostate biopsies in Chinese population. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 63338–63341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryvenko, O.N.; Epstein, J.I.; Meier, F.A.; Gupta, N.S.; Menon, M.; Diaz, M. Correlation of High Body Mass Index with More Advanced Localized Prostate Cancer at Radical Prostatectomy Is Not Reflected in PSA Level and PSA Density but Is Seen in PSA Mass. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2015, 144, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, B.; Brierley, J.; Byrd, D.; Bosman, F.; Kehoe, S.; Kossary, C.; Piñeros, M.; Van Eycken, E.; Weir, H.K.; Gospodarowicz, M. The TNM classification of malignant tumours-towards common understanding and reasonable expectations. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amling, C.L.; Riffenburgh, R.H.; Sun, L.; Moul, J.W.; Lance, R.S.; Kusuda, L.; Sexton, W.J.; Soderdahl, D.W.; Donahue, T.F.; Foley, J.P.; et al. Pathologic variables and recurrence rates as related to obesity and race in men with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nunzio, C.; Freedland, S.J.; Miano, L.; Finazzi Agrò, E.; Bañez, L.; Tubaro, A. The uncertain relationship between obesity and prostate cancer: An Italian biopsy cohort analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 37, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avogaro, A. Diabetes and obesity: The role of stress in the development of cancer. Endocrine 2024, 86, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.H.; Chen, X.Y.; Yan, Y.; Cheng, A.Y.; Lin, J.Y.; Jiang, Y.X.; Chen, H.Z.; Jin, J.M.; Luan, X. Targeting metabolism to enhance immunotherapy within tumor microenvironment. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 2011–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, B.; Iiritano, S.; Nocera, A.; Possidente, K.; Nevolo, M.T.; Ventura, V.; Foti, D.; Chiefari, E.; Brunetti, A. Insulin resistance and cancer risk: An overview of the pathogenetic mechanisms. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012, 2012, 789174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baio, R.; Napodano, G.; Caruana, C.; Molisso, G.; Di Mauro, U.; Intilla, O.; Pane, U.; D’Angelo, C.; Francavilla, A.B.; Guarnaccia, C.; et al. Association between obesity and frequency of high-grade prostate cancer on biopsy in men: A single-center retrospective study. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 17, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.E.; Oelfke, U.; McNair, H.A.; Tree, A.C. GI factors, potential to predict prostate motion during radiotherapy; a scoping review. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2023, 40, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Tilling, K.; Turner, E.L.; Martin, R.M.; Lennon, R.; Lane, J.A.; Donovan, J.L.; Hamdy, F.C.; Neal, D.E.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the associations between body mass index, prostate cancer, advanced prostate cancer, and prostate-specific antigen. Cancer Causes Control 2020, 31, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Chen, J.; Zheng, Q.; Xie, Y.; Cao, Y. Causal association between obesity and hypothyroidism: A two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1287463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ma, J. Body mass index, prostate cancer-specific mortality, and biochemical recurrence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, L.C.; Chery, L.J.; Hu, E.Y.; Zeliadt, S.B.; Holt, S.K.; Lin, D.W.; Porter, M.P.; Gore, J.L.; Wright, J.L. Metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia and prostate cancer recurrence after primary surgery or radiation in a veterans cohort. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015, 18, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, M.J.; Clark, A.K.; Selth, L.A.; Haynes, V.R.; Lister, N.; Rebello, R.; Porter, L.H.; Niranjan, B.; Whitby, S.T.; Lo, J.; et al. Suppressing fatty acid uptake has therapeutic effects in preclinical models of prostate cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaau5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, F.; Anselmi, M.; Carollo, E.; Sartori, P.; Procacci, P.; Carter, D.; Limonta, P. Adipocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Promote Prostate Cancer Cell Aggressiveness by Enabling Multiple Phenotypic and Metabolic Changes. Cells 2022, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Hu, M.B.; Bai, P.D.; Zhu, W.H.; Liu, S.H.; Hou, J.Y.; Xiong, Z.Q.; Ding, Q.; Jiang, H.W. Proinflammatory cytokines in prostate cancer development and progression promoted by high-fat diet. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 249741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Scherer, P.E. Update on Adipose Tissue and Cancer. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Liang, C. Exosomes That Have Different Cellular Origins Followed by the Impact They Have on Prostate Tumor Development in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Rep. 2024, 7, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Y.X.; Wang, Y.S.; Zhou, J.L. Lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and prostate cancer: A crucial metabolic journey. Asian J. Androl. 2024, 26, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J.I.; Egevad, L.; Amin, M.B.; Delahunt, B.; Srigley, J.R.; Humphrey, P.A.; Grading Committee. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma: Definition of Grading Patterns and Proposal for a New Grading System. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, K.; Sun, M.; Larcher, A.; Blanc-Lapierre, A.; Schiffmann, J.; Graefen, M.; Sosa, J.; Saad, F.; Parent, M.É.; Karakiewicz, P.I. Waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, body mass index, and prostate cancer risk: Results from the North-American case-control study Prostate Cancer & Environment Study. Urol. Oncol. 2015, 33, 494.e1–494.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briganti, A.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Chun, F.K.; Suardi, N.; Gallina, A.; Abdollah, F.; Freschi, M.; Doglioni, C.; Rigatti, P.; Montorsi, F. Obesity does not increase the risk of lymph node metastases in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy and extended pelvic lymph node dissection. Int. J. Urol. 2009, 16, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capitanio, U.; Suardi, N.; Briganti, A.; Gallina, A.; Abdollah, F.; Lughezzani, G.; Salonia, A.; Freschi, M.; Montorsi, F. Influence of obesity on tumour volume in patients with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012, 109, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamie, K.; Oberfoell, S.; Kwan, L.; Labo, J.; Wei, J.T.; Litwin, M.S. Body mass index and prostate cancer severity: Do obese men harbor more aggressive disease on prostate biopsy? Urology 2013, 81, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulou, P.; Martin, R.M.; Turner, E.L.; Lane, J.A.; Gilbert, R.; Davis, M.; Donovan, J.L.; Hamdy, F.C.; Neal, D.E. Association of obesity with prostate cancer: A case-control study within the population-based PSA testing phase of the ProtecT study. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, S.J.; Isaacs, W.B.; Mangold, L.A.; Yiu, S.K.; Grubb, K.A.; Partin, A.W.; Epstein, J.I.; Walsh, P.C.; Platz, E.A. Stronger association between obesity and biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy among men treated in the last 10 years. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 2883–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedland, S.J.; Branche, B.L.; Howard, L.E.; Hamilton, R.J.; Aronson, W.J.; Terris, M.K.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Amling, C.L.; Kane, C.J.; SEARCH Database Study Group. Obesity, risk of biochemical recurrence, and prostate-specific antigen doubling time after radical prostatectomy: Results from the SEARCH database. BJU Int. 2019, 124, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geybels, M.S.; Verhage, B.A.; Arts, I.C.; van Schooten, F.J.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. Dietary flavonoid intake, black tea consumption, and risk of overall and advanced stage prostate cancer. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Nagamatsu, H.; Teishima, J.; Kohada, Y.; Fujii, S.; Kurimura, Y.; Mita, K.; Shigeta, M.; Maruyama, S.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Body mass index as a classifier to predict biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy in patients with lower prostate-specific antigen levels. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hammarsten, J.; Högstedt, B. Clinical, haemodynamic, anthropometric, metabolic and insulin profile of men with high-stage and high-grade clinical prostate cancer. Blood Press 2004, 13, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, N.; Matsushima, M.; Kido, M.; Naruoka, T.; Furuta, A.; Furuta, N.; Takahashi, H.; Egawa, S. BMI is associated with larger index tumors and worse outcome after radical prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014, 17, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbarn, H.; Jeldres, C.; Budäus, L.; Salomon, G.; Schlomm, T.; Steuber, T.; Chun, F.K.; Ahyai, S.; Capitanio, U.; Haese, A.; et al. Effect of body mass index on histopathologic parameters: Results of large European contemporary consecutive open radical prostatectomy series. Urology 2009, 73, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentzmik, F.; Schnoeller, T.J.; Cronauer, M.V.; Steinestel, J.; Steffens, S.; Zengerling, F.; Al Ghazal, A.; Schrader, M.G.; Steinestel, K.; Schrader, A.J. Corpulence is the crucial factor: Association of testosterone and/or obesity with prostate cancer stage. Int. J. Urol. 2014, 21, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Yamada, M.; Ohji, S.; Ishiyama, D.; Nishio, N.; Otobe, Y.; Koyama, S.; Suzuki, M.; Ichikawa, T.; Ito, D.; et al. Presence of sarcopenic obesity and evaluation of the associated muscle quality in Japanese older men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2019, 10, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaru, A.; Kamiya, N.; Suzuki, H.; Endo, T.; Takano, M.; Yano, M.; Kawamura, K.; Imamoto, T.; Ichikawa, T. Implications of body mass index in Japanese patients with prostate cancer who had undergone radical prostatectomy. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 40, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, K.C.; Yoon, Y.E.; Rha, K.H.; Chung, B.H.; Yang, S.C.; Hong, S.J. Low body mass index is associated with adverse oncological outcomes following radical prostatectomy in Korean prostate cancer patients. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2014, 46, 1935–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlais, C.S.; Cowan, J.E.; Neuhaus, J.; Kenfield, S.A.; Van Blarigan, E.L.; Broering, J.M.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Carroll, P.; Chan, J.M. Obesity at Diagnosis and Prostate Cancer Prognosis and Recurrence Risk Following Primary Treatment by Radical Prostatectomy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Ritch, C.; Desai, M.; Benson, M.C.; McKiernan, J.M. The interaction of body mass index and race in predicting biochemical failure after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2011, 107, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maj-Hes, A.B.; Mathieu, R.; Özsoy, M.; Soria, F.; Moschini, M.; Abufaraj, M.; Briganti, A.; Roupret, M.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Klatte, T.; et al. Obesity is associated with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy: A multi-institutional extended validation study. Urol. Oncol. 2017, 35, 460.e1–460.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourão, T.C.; de Oliveira, R.A.R.; Favaretto, R.L.; Santana, T.B.M.; Sacomani, C.A.R.; Bachega, W., Jr.; Guimarães, G.C.; Zequi, S.C. Should obesity be associated with worse urinary continence outcomes after robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy? a propensity score matching analysis. Int. Braz J. Urol. 2022, 48, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, D.; Pickles, T.; Tyldesley, S.; Prostate Cohort Outcomes Initiative. Obesity as a predictor of biochemical recurrence and survival after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007, 100, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado-Montilla, J.; Soto Salgado, M.; Surillo Trautmann, B.; Sánchez-Ortiz, R.; Irizarry-Ramírez, M. Association of serum lipid levels and prostate cancer severity among Hispanic Puerto Rican men. Lipids Health Dis. 2015, 14, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffmann, J.; Salomon, G.; Tilki, D.; Budäus, L.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Leyh-Bannurah, S.R.; Pompe, R.S.; Haese, A.; Heinzer, H.; Huland, H.; et al. Radical prostatectomy neutralizes obesity-driven risk of prostate cancer progression. Urol. Oncol. 2017, 35, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Inman, B.A.; Sengupta, S.; Slezak, J.M.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Leibovich, B.C.; Zincke, H.; Blute, M.L. Obesity and survival after radical prostatectomy: A 10-year prospective cohort study. Cancer 2006, 107, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroup, S.P.; Cullen, J.; Auge, B.K.; L’Esperance, J.O.; Kang, S.K. Effect of obesity on prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer as measured by the 2006 Radiation Therapy Oncology Group-American Society for Therapeutic Radiation and Oncology (RTOG-ASTRO) Phoenix consensus definition. Cancer 2007, 110, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, A.C.; Howard, L.E.; Sun, S.X.; Cooperberg, M.R.; Kane, C.J.; Aronson, W.J.; Terris, M.K.; Amling, C.L.; Freedland, S.J. Obesity and prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy: Results from the Shared Equal Access Regional Cancer Hospital (SEARCH) database. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017, 20, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Murphy, C.T.; Ruth, K.; Zaorsky, N.G.; Smaldone, M.C.; Sobczak, M.L.; Kutikov, A.; Viterbo, R.; Horwitz, E.M. Impact of obesity on outcomes after definitive dose-escalated intensity-modulated radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer 2015, 121, 3010–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.D.; Byun, S.S.; Lee, S.E.; Hong, S.K. Impact of Body Mass Index on Oncological Outcomes of Prostate Cancer Patients after Radical Prostatectomy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Toker, M.; Shyr, W.; Fram, E.; Watts, K.L.; Agalliu, I. Association of Obesity and Diabetes with Prostate Cancer Risk Groups in a Multiethnic Population. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2022, 20, 299–299.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, A.C.; Manco, R.; Tirabassi, G.; Balercia, G.; Tirabassi, G. Relationship between BMI, PSA and Histopathological Tumor Grade in a Caucasian Population Affected by Prostate Cancer. Glob. J. Med. Clin. Case Rep. 2014, 1, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gallina, A.; Karakiewicz, P.I.; Hutterer, G.C.; Chun, F.K.; Briganti, A.; Walz, J.; Antebi, E.; Shariat, S.F.; Suardi, N.; Graefen, M.; et al. Obesity does not predispose to more aggressive prostate cancer either at biopsy or radical prostatectomy in European men. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, E.; Rizzo, A.; Santa, K.; Jirillo, E. Associations between “Cancer Risk”, “Inflammation” and “Metabolic Syndrome”: A Scoping Review. Biology 2024, 13, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, C.; Meier, M.; Schmid, H.P. Nutrition, dietary supplements and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Maturitas 2011, 70, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, P.J.; Katz, A.E. Diet and prostate cancer—A holistic approach to management. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2011, 64, 720–734. [Google Scholar]

- Srihari, S.; Kwong, R.; Tran, K.; Simpson, R.; Tattam, P.; Smith, E. Metabolic deregulation in prostate cancer. Mol. Omics 2018, 14, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Kolonin, M.G.; DiGiovanni, J. Obesity and prostate cancer—Microenvironmental roles of adipose tissue. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2023, 20, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nunzio, C.; Albisinni, S.; Freedland, S.J.; Miano, L.; Cindolo, L.; Finazzi Agrò, E.; Autorino, R.; De Sio, M.; Schips, L.; Tubaro, A. Abdominal obesity as risk factor for prostate cancer diagnosis and high grade disease: A prospective multicenter Italian cohort study. Urol. Oncol. 2013, 31, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, B.A.; Martin, E.C.; Matossian, M.D.; Brock, C.K.; Nguyen, K.; Collins-Burow, B.; Burow, M.E. The effect of obesity on adipose-derived stromal cells and adipose tissue and their impact on cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2022, 41, 549–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegfried, G.; Descarpentrie, J.; Evrard, S.; Khatib, A.M. Proprotein convertases: Key players in inflammation-related malignancies and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2020, 473, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancel, M.; Pouillot, W.; Mahéo, K.; Fontaine, A.; Crottès, D.; Fromont, G. Interplay between Prostate Cancer and Adipose Microenvironment: A Complex and Flexible Scenario. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadani, F.G.; Perdana, N.R.; Ringoringo, D.R.L. Body mass index, obesity and risk of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cent. Eur. J. Urol. 2024, 77, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).