Reversing the Irreversible: miRNA-Targeting Mesyl Phosphoramidate Oligonucleotides Restore Sensitivity to Cisplatin and Doxorubicin of KB-8-5 Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Oligonucleotides

2.2. Cell Lines

2.3. Transfection of Tumor Cells with ASOs

2.4. Cell Viability Test (MTT)

2.5. xCelligence Real-Time Analysis of Cell Proliferation and Viability

2.6. qPCR

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Rhodamine 123 Accumulation Assay

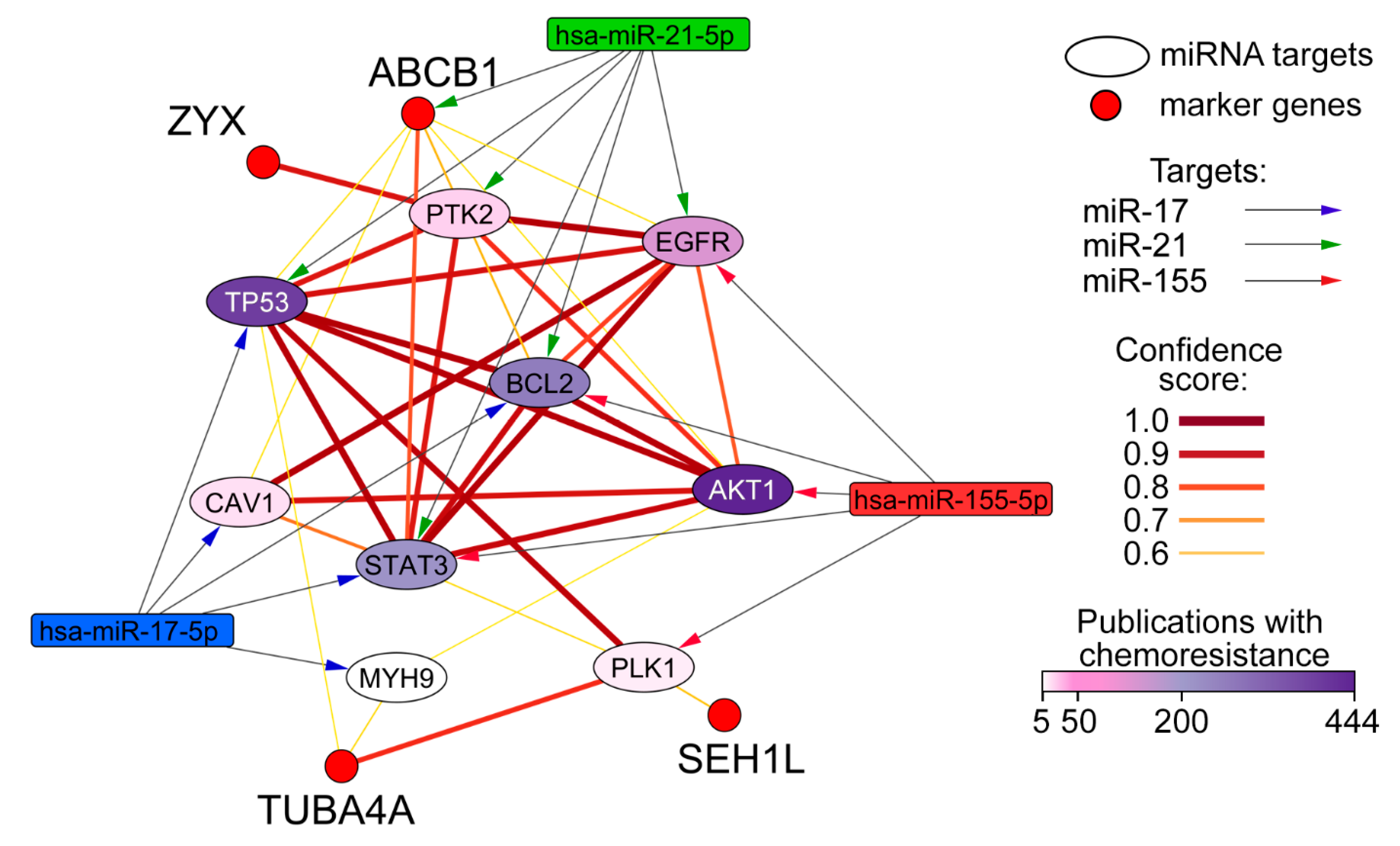

2.9. Reconstruction and Analysis of miRNA-Target Networks

2.10. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Optimal Scheme of Concurrent Application of µ-ASO Targeted to miR-17, miR-21, and miR-155 with Cytostatics (Cis/Dox)

- Simultaneous treatment, in which chemotherapeutic agents were added immediately after a 4 h cell incubation with µ-ASOs/2X3-DOPE lipoplexes needed for transfection (total incubation time with µ-ASO 48 h) (Scheme A, Figure S2a);

- Pre-treatment for 24 h, where cells were transfected with the oligonucleotide 24 h prior to cytostatic addition (total incubation time with µ-ASO 72 h) (Scheme B, Figure S2b);

- Pre-treatment for 48 h, where oligonucleotide transfection preceded drug exposure by 48 h (total incubation time with µ-ASO 96 h) (Scheme C, Figure S2c).

3.1.1. Regimens of Concurrent Application of μ-ASOs and Cisplatin

3.1.2. Regimens of Concurrent Application of μ-ASOs and Doxorubicin

3.2. Revealing the Type of Interaction Between µ-ASO and Cytostatics Applied Together on KB-8-5 Cells (Additive/Synergistic Effects)

3.3. Uncovering the Biological Effects of Concurrent Application of Cytostatics and μ-ASO in Optimal Concentrations

3.4. Evaluation of Possible Molecular Mechanisms Underlying µ-ASO Action Leading to the Sensitization of KB-8-5 Cells to the Cytostatics

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimization of Combination Regimens

4.2. Mechanistic Interplay Between µ-ASO and Cytostatics

4.2.1. Divergent Effects Exerted by µ-ASOs and Cytostatics

4.2.2. Complementary and Potentiating Interactions Between µ-ASOs and Cytostatic Agents

Coordinated Impact on Cell Cycle Regulation and DNA Repair

Complementary Modulation of Cellular Metabolism and Translational Acitivity

4.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2X3-DOPE | polycationic lipid 1,26-bis(cholest-5-en-3β-yloxycarbonylamino)-7,11,16,20-tetraazahexacosane tetrahydrochloride 2X3 and helper lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) |

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ABCB1, ABCC, BCRP (ABCG2) | ABC subfamily B member 1, subfamily C members, subfamily G member 2 |

| AKT1 | RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase |

| anti-miR | Antisense oligonucleotides targeting miR |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotides |

| ATG7 | Autophagy related 7 |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| Bcl-2 | BCL2 Apoptosis Regulator |

| BTG3 | BTG Anti-Proliferation Factor 3 |

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CHOP | Cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisone |

| Cis | Cisplatin |

| CPG | Controlled Pore Glass |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| DCK | Deoxycytidine kinase |

| DEDD | Death effector domain containing |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMTr | 5′-dimethoxytrityl |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| Dox | Doxorubucun |

| DUBR | DPPA2 upstream binding RNA |

| ECL | Excellent Chemiluminescent Substrate |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 |

| EZH1 | Enhancer of zeste 1 |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| FOXO3 | Forkhead box O3 |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| hMSH2 | Human DNA MutS homolog 2 |

| HOTAIR1 | HOX transcript antisense RNA 1 |

| HPRT1 | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 |

| HSA | Highest single agent |

| HS-qPCR | High sensitive quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| IC50 | Half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| mA | Milliampere |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCF-7 | Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 |

| MDA-MB-231 | M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Mammary Gland / Breast 231 |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| miRNA, miR | Micro ribonucleic acid |

| MMR | Mismatch repair |

| M-MuLV-RH-revertase | Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase with lacked RNase H activity |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| MRP1 | Multidrug-resistance like protein 1 |

| MSH2 | MutS Homolog 2 |

| MTT | Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide |

| MYD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 |

| MYH9 | Myosin heavy chain 9 |

| NF | Nuclear factor |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| NUP | Nucleoporins |

| ON | Oligonucleotide |

| PAGE | Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PDCD4 | Programmed cell death protein 4 |

| PLK1 | Polo like kinase 1 |

| PPI | Protein–protein interaction |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| PTK2 | Protein tyrosine kinase 2 |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| Rho123 | Rhodamine 123 |

| RhoA, B | Ras homolog family members A, B |

| RIPA | Radioimmunoprecipitation assay |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNase | Ribonuclease |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RTCA | Real-time cell analysis |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| SEH1L | SEH1 like nucleoporin |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TBST | TBS and Tween 20 mix |

| TFRC | Transferrin receptor |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| TIMP3 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 |

| TNFAIP8 | Tumor necrosis factor-α-inducible protein 8 |

| TP53 | Tumor protein p53 |

| TSPAN5 | Tetraspanin-5 |

| TUBA4A | Tubulin alpha-4A |

| ZYX | Zyxin |

| ΔΔCt | Delta delta cycle threshold |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Gupta, S. Cancer Treatment Therapies: Traditional to Modern Approaches to Combat Cancers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 9663–9676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Jin, G.; He, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, F.; Guo, H. Mechano-Assisted Strategies to Improve Cancer Chemotherapy. Life Sci. 2024, 359, 123178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, A.M.; Mott, J.L. Overview of MicroRNA Biology. Semin. Liver Dis. 2015, 35, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shi, S.; Xie, H.; Peng, X.; Yin, W.; Tao, Y.; et al. MiRNA-Based Biomarkers, Therapies, and Resistance in Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 2628–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudelot, K.; Gibier, J.B.; Pottier, N.; Hémon, B.; Van Seuningen, I.; Glowacki, F.; Leroy, X.; Cauffiez, C.; Gnemmi, V.; Aubert, S.; et al. Targeting MiR-21 Decreases Expression of Multi-Drug Resistant Genes and Promotes Chemosensitivity of Renal Carcinoma. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317707372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyan, W.; Yang, L. MicroRNA-21 Regulates the Sensitivity to Cisplatin in a Human Osteosarcoma Cell Line. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 185, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comincini, S.; Allavena, G.; Palumbo, S.; Morini, M.; Durando, F.; Angeletti, F.; Pirtoli, L.; Miracco, C. MicroRNA-17 Regulates the Expression of ATG7 and Modulates the Autophagy Process, Improving the Sensitivity to Temozolomide and Low-Dose Ionizing Radiation Treatments in Human Glioblastoma Cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2013, 14, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, J.; Jian, H.; Chang, H. Role of Micro-RNAs in Drug Resistance of Multiple Myeloma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Xia, M.; Niu, X. DUBR/MiR-17-3p/TFRC/HO-1 Axis Promotes the Chemosensitivity of Multiple Myeloma. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2025, 35, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Hou, J.; Liu, C.; Shan, F.; Xiong, X.; Qin, A.; Chen, J.; Ren, W. The Long Non-Coding RNA HOTAIRM1 Suppresses Cell Progression via Sponging Endogenous MiR-17-5p/ B-Cell Translocation Gene 3 (BTG3) Axis in 5-Fluorouracil Resistant Colorectal Cancer Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, S.; Yuan, J.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Lv, Z.; Yu, W.; Duan, S.; Hu, Y. Reverse Multidrug Resistance in Human HepG2/ADR by Anti-MiR-21 Combined with Hyperthermia Mediated by Functionalized Gold Nanocages. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 3767–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Ryu, Y.; Choi, J.; Park, D.; Lee, J.W.; Chi, S.G.; Kim, S.H.; Yang, Y. Targeting MiR-21 to Overcome P-Glycoprotein Drug Efflux in Doxorubicin-Resistant 4T1 Breast Cancer. Biomater. Res. 2024, 28, 0095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, L.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, K.; Fan, D. MicroRNA-21: A Therapeutic Target for Reversing Drug Resistance in Cancer. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2013, 17, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, F.; Dong, H.; Jia, X.; Guo, W.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y.; Ju, H.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y. Functionalized Graphene Oxide Mediated Adriamycin Delivery and MiR-21 Gene Silencing to Overcome Tumor Multidrug Resistance In Vitro. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wu, G. CircRNA-001241 Mediates Sorafenib Resistance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by Sponging MiR-21-5p and Regulating TIMP3 Expression. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 45, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Ren, L.; Lin, L.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, J. Effect of MicroRNA-21 on Multidrug Resistance Reversal in A549/DDP Human Lung Cancer Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayraktar, R.; Van Roosbroeck, K. MiR-155 in Cancer Drug Resistance and as Target for MiRNA-Based Therapeutics. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Y.; Yan, B.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C. Andrographis Modulates Cisplatin Resistance in Lung Cancer via MiR-155-5p/SIRT1 Axis. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, A.A.; Gondaliya, P.; Mali, M.; Pawar, A.; Bhat, P.; Khairnar, A.; Arya, N.; Kalia, K. MiR-155 Inhibitor-Laden Exosomes Reverse Resistance to Cisplatin in a 3D Tumor Spheroid and Xenograft Model of Oral Cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 3010–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Lv, M.; Chen, W.; Zhong, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Ma, T.; Tang, J.; Zhao, J. Role of MiR-155 in Drug Resistance of Breast Cancer. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Wu, X.J.; Liang, Y.; Ye, G.Q.; Che, Y.C.; Wu, X.Z.; Zhu, X.J.; Fan, H.L.; Fan, X.P.; Xu, J.F. MiR-155 Increases Stemness and Decitabine Resistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells by Inhibiting TSPAN5. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, T.; Yan, L.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, W.; Chen, C.; et al. MiR-155-3p Acts as a Tumor Suppressor and Reverses Paclitaxel Resistance via Negative Regulation of MYD88 in Human Breast Cancer. Gene 2019, 700, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastgoo, N.; Wu, J.; Liu, A.; Pourabdollah, M.; Atenafu, E.G.; Reece, D.; Chen, W.; Chang, H. Targeting CD47/TNFAIP8 by MiR-155 Overcomes Drug Resistance and Inhibits Tumor Growth through Induction of Phagocytosis and Apoptosis in Multiple Myeloma. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, S.; Patutina, O. Enhanced Inhibition of Tumorigenesis Using Combinations of MiRNA-Targeted Therapeutics. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, S.K.; Patutina, O.A.; Burakova, E.A.; Chelobanov, B.P.; Fokina, A.A.; Vlassov, V.V.; Altman, S.; Zenkova, M.A.; Stetsenko, D.A. Mesyl Phosphoramidate Antisense Oligonucleotides as an Alternative to Phosphorothioates with Improved Biochemical and Biological Properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patutina, O.; Gaponova, S.K.; Sen’kova, A.V.; Savin, I.A.; Gladkikh, D.V.; Burakova, E.A.; Fokina, A.A.; Maslov, M.A.; Shmendel’, E.V.; Wood, M.J.A.; et al. Mesyl Phosphoramidate Backbone Modified Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting MiR-21 with Enhanced in Vivo Therapeutic Potency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 32370–32379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaponova, S.; Patutina, O.; Sen’kova, A.; Burakova, E.; Savin, I.; Markov, A.; Shmendel, E.; Maslov, M.; Stetsenko, D.; Vlassov, V.; et al. Single Shot vs. Cocktail: A Comparison of Mono- and Combinative Application of MiRNA-Targeted Mesyl Oligonucleotides for Efficient Antitumor Therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engle, K.; Kumar, G. Cancer Multidrug-Resistance Reversal by ABCB1 Inhibition: A Recent Update. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 239, 114542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moralev, A.D.; Markov, O.V.; Zenkova, M.A.; Markov, A.V. Novel Cross-Cancer Hub Genes in Doxorubicin Resistance Identified by Transcriptional Mapping. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabilova, T.O.; Shmendel, E.V.; Gladkikh, D.V.; Chernolovskaya, E.L.; Markov, O.V.; Morozova, N.G.; Maslov, M.A.; Zenkova, M.A. Targeted Delivery of Nucleic Acids into Xenograft Tumors Mediated by Novel Folate-Equipped Liposomes. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 123, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshchepkova, A.; Chernikov, I.; Miroshnichenko, S.; Patutina, O.; Markov, O.; Savin, I.; Staroseletz, Y.; Meschaninova, M.; Puchkov, P.; Zhukov, S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle Mimetics as Delivery Vehicles for Oligonucleotide-Based Therapeutics and Plasmid DNA. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1437817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, B.; Lawlor, D.; Gillet, J.P.; Gottesman, M.; O’Leary, J.; Stordal, B. Collateral Sensitivity to Cisplatin in KB-8-5-11 Drug-Resistant Cancer Cells. PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24403508/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Stojanović, M.; Lalatović, J.; Milosavljević, A.; Savić, N.; Simms, C.; Radosavljević, B.; Ćetković, M.; Kravić Stevović, T.; Mrda, D.; Čolović, M.B.; et al. In Vivo Toxicity Evaluation of a Polyoxotungstate Nanocluster as a Promising Contrast Agent for Computed Tomography. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Higgins, B.; Ju, G.; Kolinsky, K.; Luk, K.C.; Packman, K.; Pizzolato, G.; Ren, Y.; Thakkar, K.; Tovar, C.; et al. Discovery of a Highly Potent, Orally Active Mitosis/Angiogenesis Inhibitor R1530 for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantari, H.; Dashtearjandi, A.A.; Kalantar, E. Genotoxicity Study of Hypiran and Chamomilla Herbal Drugs Determined by in Vivo Supervital Micronucleus Assay with Mouse Peripheral Reticulocytes. Acta Biol. Hung. 2009, 60, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, S.; Patutina, O.; Markov, A.; Kupryushkin, M.; Vlassov, V.; Zenkova, M. Biological performance and molecular mechanisms of mesyl microRNA-targeted oligonucleotides in colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, A. Hormetic Effects in Pharmacology: Pharmacological Inversions as Prototypes for Hormesis. Health Phys. 1987, 52, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L.; Glänzel, W.; Korch, C.; Capes-Davis, A. Widespread Use of Misidentified Cell Line KB (HeLa): Incorrect Attribution and Its Impact Revealed through Mining the Scientific Literature. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2784–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaussen, K.A.; Dunant, A.; Fouret, P.; Brambilla, E.; André, F.; Haddad, V.; Taranchon, E.; Filipits, M.; Pirker, R.; Popper, H.H.; et al. DNA Repair by ERCC1 in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer and Cisplatin-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.J.; Kasman, L.M.; Kelly, M.M.; Lu, P.; Spruill, L.; McDermott, P.J.; Voelkel-Johnson, C. Doxorubicin Generates a Pro-Apoptotic Phenotype by Phosphorylation of EF-2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senichkin, V.V.; Streletskaia, A.Y.; Gorbunova, A.S.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Kopeina, G.S. Saga of Mcl-1: Regulation from Transcription to Degradation. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletto, R.E.; Ofner, C.M. Cytotoxic Mechanisms of Doxorubicin at Clinically Relevant Concentrations in Breast Cancer Cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2022, 89, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makovec, T. Cisplatin and Beyond: Molecular Mechanisms of Action and Drug Resistance Development in Cancer Chemotherapy. Radiol. Oncol. 2019, 53, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, M.; Castilla, J.; Alonso, C.; Pérez, J. Cisplatin Biochemical Mechanism of Action: From Cytotoxicity to Induction of Cell Death through Interconnections between Apoptotic and Necrotic Pathways. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenska, M.; Balvan, J.; Fojtu, M.; Gumulec, J.; Masarik, M. Unexpected Therapeutic Effects of Cisplatin. Metallomics 2019, 11, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikov, S.V.; Söll, D.; Steitz, T.A.; Polikanov, Y.S. Insights into RNA Binding by the Anticancer Drug Cisplatin from the Crystal Structure of Cisplatin-Modified Ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 4978–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Tian, H.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X. MiRNA Oligonucleotide and Sponge for MiRNA-21 Inhibition Mediated by PEI-PLL in Breast Cancer Therapy. Acta Biomater. 2015, 25, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatami, F.; Matin, M.M.; Danesh, N.M.; Bahrami, A.R.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M. Targeted Delivery System Using Silica Nanoparticles Coated with Chitosan and AS1411 for Combination Therapy of Doxorubicin and AntimiR-21. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 266, 118111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Hwang, J.; Song, Y.; Kim, S.; Park, N. Anti-MiR21-Conjugated DNA Nanohydrogel for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Biomater. Adv. 2025, 169, 214160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Songlin, P.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jinhui, W. MiR-21 Inhibitor Sensitizes Human OSCC Cells to Cisplatin. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 5481–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Nie, W.; Qiu, B.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J. Inhibition of MicroRNA-17 Enhances Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis of Human Tongue Squamous Carcinoma Cell. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2021, 53, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.M.; Hong, X.W.; Wang, L.L.; Cui, X.F.; Lu, J.; Chen, G.Q.; Zheng, Y.L. MicroRNA-17 Inhibition Overcomes Chemoresistance and Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition through a DEDD-Dependent Mechanism in Gastric Cancer. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 102, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Ning, L.; Wang, L.; Ouyang, T.; Qi, L.; Yang, R.; Wu, Y. MiR-21 Inhibition Reverses Doxorubicin-Resistance and Inhibits PC3 Human Prostate Cancer Cells Proliferation. Andrologia 2021, 53, e14016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ASO | Sequence 5′-3′ |

|---|---|

| μ-17 | CμTμAμCμCμTμGμCμAμCμTμGμTμAμAμGμCμAμCμTμTμTμG |

| μ-21 | TμCμAμAμCμAμTμCμAμGμTμCμTμGμAμTμAμAμGμCμTμA |

| μ-155 | AμAμCμCμCμCμTμAμTμCμAμCμGμAμTμTμAμGμCμAμTμTμAμA |

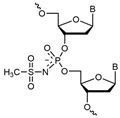

| μ-Scr (Scramble control) | CμAμAμGμTμCμTμCμGμTμAμTμGμTμAμGμTμGμGμTμT μ-oligonucleotide structure |

| PCR Primer | Sequence 5′-3′ |

| ABCB1-F | AATGGCTACATGAGAGCGGAG |

| ABCB1-R | AATGTTCTGGCTTCCGTTGC |

| HPRT-F | CATCAAAGCACTGAATAGAAAT |

| HPRT-R | TATCTTCCACAATCAAGACATT |

| SEH1L-F | ATAGCGACCAAAGATGTGAG |

| SEH1L-R | CGCCAGACCTGAGAATTATG |

| TUBA4A-F | ATCATTGACCCAGTGCTG |

| TUBA4A-R | CTTGCCATAGTCAACAGAGAG |

| ZYX-F | GCCCTGGACAAGAACTTC |

| ZYX-R | CATCTGCCTCAATCGACAG |

| GAPDH-F | TGCACCACCAAC TGCTTAGC |

| GAPDH-R | GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miroshnichenko, S.; Demirel, R.; Moralev, A.; Almieva, O.; Markov, A.; Burakova, E.; Stetsenko, D.; Maslov, M.; Vlassov, V.; Zenkova, M. Reversing the Irreversible: miRNA-Targeting Mesyl Phosphoramidate Oligonucleotides Restore Sensitivity to Cisplatin and Doxorubicin of KB-8-5 Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123118

Miroshnichenko S, Demirel R, Moralev A, Almieva O, Markov A, Burakova E, Stetsenko D, Maslov M, Vlassov V, Zenkova M. Reversing the Irreversible: miRNA-Targeting Mesyl Phosphoramidate Oligonucleotides Restore Sensitivity to Cisplatin and Doxorubicin of KB-8-5 Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123118

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiroshnichenko, Svetlana, Rabia Demirel, Arseny Moralev, Olga Almieva, Andrey Markov, Ekaterina Burakova, Dmitry Stetsenko, Mikhail Maslov, Valentin Vlassov, and Marina Zenkova. 2025. "Reversing the Irreversible: miRNA-Targeting Mesyl Phosphoramidate Oligonucleotides Restore Sensitivity to Cisplatin and Doxorubicin of KB-8-5 Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123118

APA StyleMiroshnichenko, S., Demirel, R., Moralev, A., Almieva, O., Markov, A., Burakova, E., Stetsenko, D., Maslov, M., Vlassov, V., & Zenkova, M. (2025). Reversing the Irreversible: miRNA-Targeting Mesyl Phosphoramidate Oligonucleotides Restore Sensitivity to Cisplatin and Doxorubicin of KB-8-5 Epidermoid Carcinoma Cells. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3118. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123118