Proteomics Reveals Differential Diagnosis Biomarkers Between Sepsis and Hemophagocytic Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Ethical Commitment

2.2. Study Endpoints

2.3. Proteomic Study

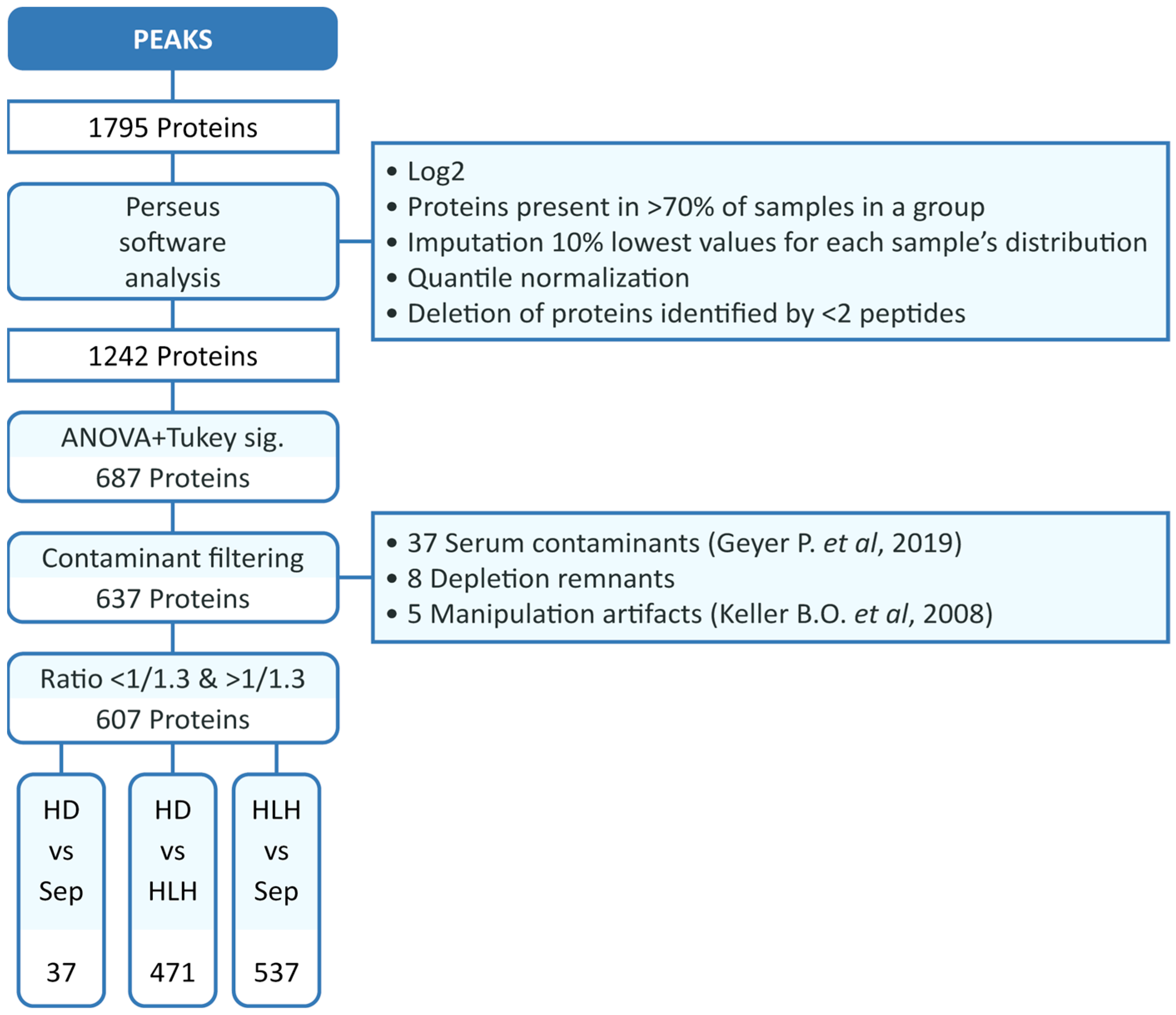

2.4. Analysis of the Serum Proteome Profile

2.5. Selection of Proteins for ELISA Validation

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Cohort

3.2. Expression Analysis of the Serum Proteome Profile

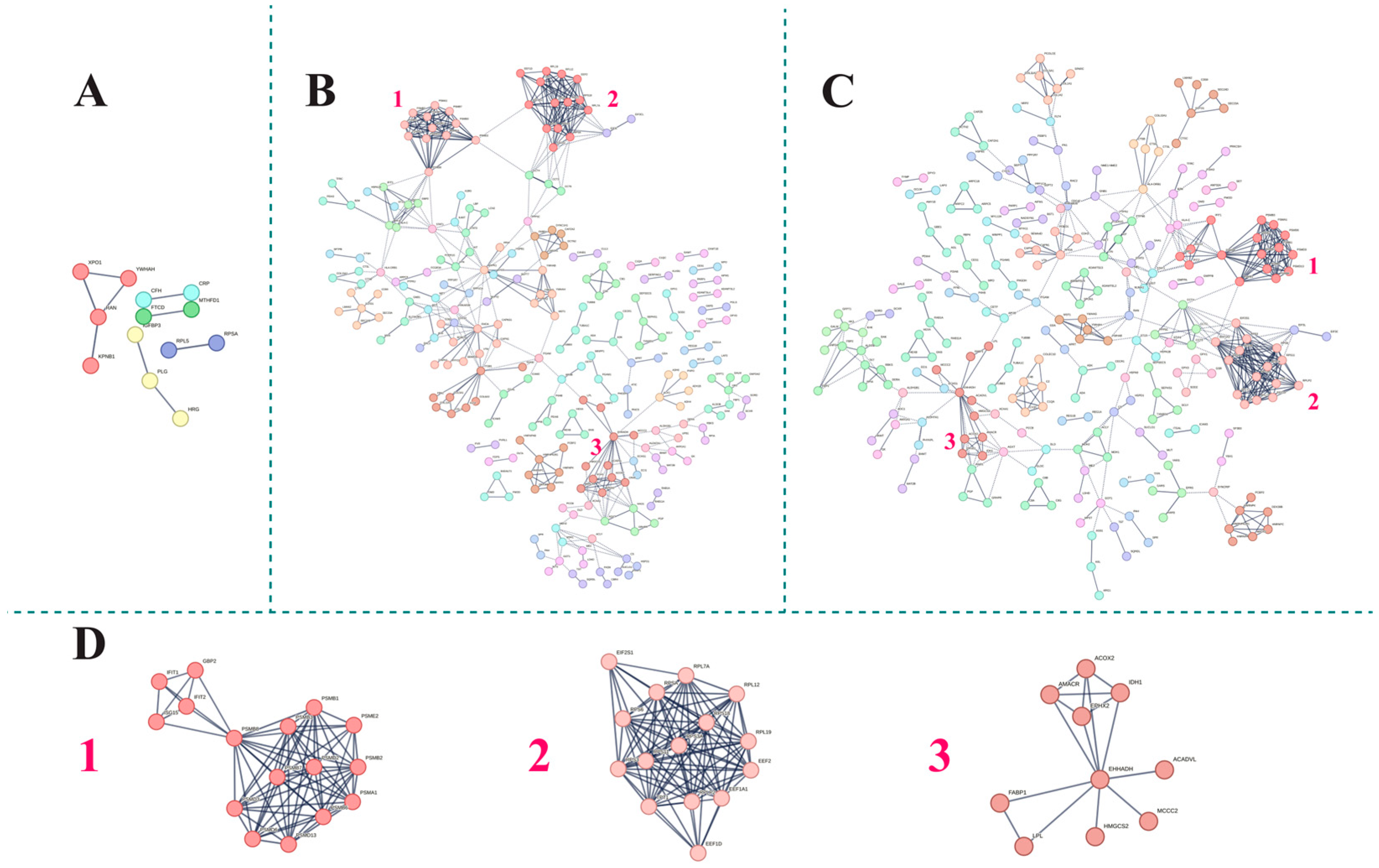

3.3. Functional Analysis of the Serum Proteome Profile

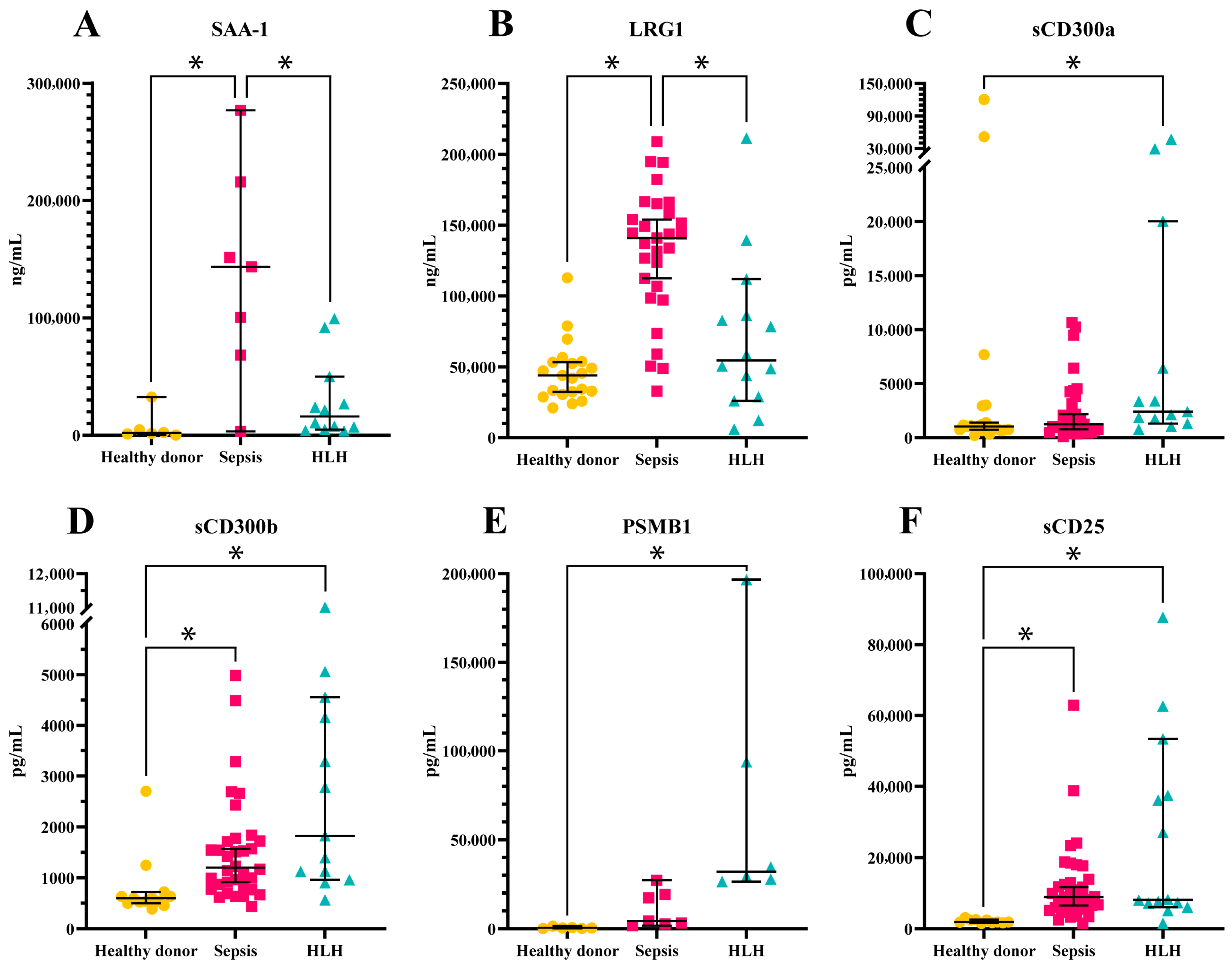

3.4. Validation of Candidate Biomarkers

3.5. ROC Analysis of Candidate Biomarkers

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HLH | Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis |

| DEP | Differentially expressed protein |

| MCL | Markov cluster algorithm |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| IPA | Ingenuity pathway analysis |

| HD | Healthy donors |

References

- Jordan, M.B.; Allen, C.E.; Greenberg, J.; Henry, M.; Hermiston, M.L.; Kumar, A.; Hines, M.; Eckstein, O.; Ladisch, S.; Nichols, K.E.; et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machowicz, R.; Janka, G.; Wiktor-Jedrzejczak, W. Similar but not the same: Differential diagnosis of HLH and sepsis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 114, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.J.; Ng, Z.Q.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Sultana, R.; Lee, J.H. Treatment and mortality of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in critically ill children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70, e30122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canna, S.W.; Marsh, R.A. Pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood 2020, 135, 1332–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henter, J.I.; Samuelsson-Horne, A.; Aricò, M.; Egeler, R.M.; Elinder, G.; Filipovich, A.H.; Gadner, H.; Imashuku, S.; Komp, D.; Ladisch, S.; et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood 2002, 100, 2367–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Scull, B.P.; Goldberg, B.R.; Abhyankar, H.A.; Eckstein, O.E.; Zinn, D.J.; Lubega, J.; Agrusa, J.; El Mallawaney, N.; Gulati, N.; et al. IFN-γ signature in the plasma proteome distinguishes pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis from sepsis and SIRS. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 3457–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henter, J.I.; Horne, A.; Aricó, M.; Egeler, R.M.; Filipovich, A.H.; Imashuku, S.; Ladisch, S.; McClain, K.; Webb, D.; Winiarski, J.; et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2007, 48, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; De Simone, G.; Boccia, G.; De Caro, F.; Pagliano, P. Sepsis and septic shock: New definitions, new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2017, 10, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, K.; Hoffmann, U.; Ansari, U.; Bertsch, T.; Borggrefe, M.; Akin, I.; Behnes, M. The Use of Biomarkers in Sepsis: A Systematic Review. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2017, 18, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann-Struzek, C.; Goldfarb, D.M.; Schlattmann, P.; Schlapbach, L.J.; Reinhart, K.; Kissoon, N. The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: A systematic review. Lancet Respir. Med. 2018, 6, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnatt, T.S.; Lilley, C.M.; Mirza, K.M. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 146, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosée, P.; Horne, A.; Hines, M.; von Bahr Greenwood, T.; Machowicz, R.; Berliner, N.; Birndt, S.; Gil-Herrera, J.; Girschikofsky, M.; Jordan, M.B.; et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood 2019, 133, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, M.R.; von Bahr Greenwood, T.; Beutel, G.; Beutel, K.; Hays, J.A.; Horne, A.; Janka, G.; Jordan, M.B.; van Laar, J.A.M.; Lachmann, G.; et al. Consensus-Based Guidelines for the Recognition, Diagnosis, and Management of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Critically Ill Children and Adults. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 50, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Reddy, P.J.; Jain, R.; Gollapalli, K.; Moiyadi, A.; Srivastava, S. Proteomic technologies for the identification of disease biomarkers in serum: Advances and challenges ahead. Proteomics 2011, 11, 2139–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Robinson, R.A. The role of proteomics in understanding biological mechanisms of sepsis. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2014, 8, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, J.R.; Zougman, A.; Nagaraj, N.; Mann, M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bai, J.; Bandla, C.; García-Seisdedos, D.; Hewapathirana, S.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Kundu, D.J.; Prakash, A.; Frericks-Zipper, A.; Eisenacher, M.; et al. The PRIDE database resources in 2022: A hub for mass spectrometry-based proteomics evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D543–D552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, P.E.; Voytik, E.; Treit, P.V.; Doll, S.; Kleinhempel, A.; Niu, L.; Müller, J.B.; Buchholtz, M.; Bader, J.M.; Teupser, D.; et al. Plasma Proteome Profiling to detect and avoid sample-related biases in biomarker studies. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e10427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, B.O.; Sui, J.; Young, A.B.; Whittal, R.M. Interferences and contaminants encountered in modern mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 627, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, X.; Turck, N.; Hainard, A.; Tiberti, N.; Lisacek, F.; Sanchez, J.-C.; Müller, M. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, T.M.; Whitlock, J.A.; Lu, X.; O’Brien, M.M.; Borowitz, M.J.; Devidas, M.; Raetz, E.A.; Brown, P.A.; Carroll, W.L.; Hunger, S.P. Bortezomib reinduction chemotherapy in high-risk ALL in first relapse: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 186, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanishi, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Izawa, K.; Isobe, M.; Ito, S.; Tsuchiya, A.; Maehara, A.; Kaitani, A.; Uchida, T.; Togami, K.; et al. A soluble form of LMIR5/CD300b amplifies lipopolysaccharide-induced lethal inflammation in sepsis. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, T.; Yan, H.; Xie, L.; Yang, Y.; Gong, L.; Tang, Z.; Tang, M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Pediatric Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: A Comparative Study with Healthy Controls, Sepsis, Critical Ill, and Active Epstein-Barr virus Infection to Identify Altered Pathways and Candidate Biomarkers. J. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 43, 1997–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilar-Orive, F.J.; Astigarraga, I.; Azkargorta, M.; Elortza, F.; Garcia-Obregon, S. A Three-Protein Panel to Support the Diagnosis of Sepsis in Children. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilli, C.; Hoeh, A.E.; De Rossi, G.; Moss, S.E.; Greenwood, J. LRG1: An emerging player in disease pathogenesis. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickle, R.A.; DeOca, K.B.; Garcia, B.L.; Mannie, M.D. Soluble CD25 imposes a low-zone IL-2 signaling environment that favors competitive outgrowth of antigen-experienced CD25high regulatory and memory T cells. Cell Immunol. 2023, 384, 104664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego, F. The CD300 molecules: An emerging family of regulators of the immune system. Blood 2013, 121, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avlas, S.; Kassis, H.; Itan, M.; Reichman, H.; Dolitzky, A.; Hazut, I.; Grisaru-Tal, S.; Gordon, Y.; Tsarfaty, I.; Karo-Atar, D.; et al. CD300b regulates intestinal inflammation and promotes repair in colitis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1050245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, O.H.; Murakami, Y.; Pena, M.Y.; Lee, H.-N.; Tian, L.; Margulies, D.H.; Street, J.M.; Yuen, P.S.; Qi, C.-F.; Krzewski, K.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced CD300b Receptor Binding to Toll-like Receptor 4 Alters Signaling to Drive Cytokine Responses that Enhance Septic Shock. Immunity 2016, 44, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebstein, F.; Kloetzel, P.M.; Krüger, E.; Seifert, U. Emerging roles of immunoproteasomes beyond MHC class I antigen processing. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 2543–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Niu, Z.; Zhou, B.; Li, P.; Qian, F. PSMB1 Negatively Regulates the Innate Antiviral Immunity by Facilitating Degradation of IKK-ε. Viruses 2019, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; Kosaka, M.; Saito, S.; Sano, T.; Tanaka, K.; Ichihara, A. Serum concentration and localization in tumor cells of proteasomes in patients with hematologic malignancy and their pathophysiologic significance. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1993, 121, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, G.A.; Moser, B.; Krenn, C.; Roth-Walter, F.; Hetz, H.; Richter, S.; Brunner, M.; Jensen-Jarolim, E.; Wolner, E.; Hoetzenecker, K.; et al. Heightened levels of circulating 20S proteasome in critically ill patients. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 35, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoeger, A.; Blau, M.; Egerer, K.; Feist, E.; Dahlmann, B. Circulating proteasomes are functional and have a subtype pattern distinct from 20S proteasomes in major blood cells. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 2079–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nissan, G.; Katzir, N.; Füzesi-Levi, M.G.; Sharon, M. Biology of the Extracellular Proteasome. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bseiso, O.; Zahdeh, A.; Isayed, O.; Mahagna, S.; Bseiso, A. The Role of Immune Mechanisms, Inflammatory Pathways, and Macrophage Activation Syndrome in the Pathogenesis of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Cureus 2022, 14, e33175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Ou, Y.; Min, W.; Liang, S.; Hua, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, P.; Yang, Z.; et al. Bortezomib inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NF-κB pathway to reduce psoriatic inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 206, 115326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; Hayden, P.J.; Will, A.; Wheatley, K.; Coyne, I. Bortezomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 4, CD010816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettari, R.; Previti, S.; Bitto, A.; Grasso, S.; Zappalà, M. Immunoproteasome-Selective Inhibitors: A Promising Strategy to Treat Hematologic Malignancies, Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Carey, H.K.; Pomatto, L.C.; Davies, K.J. The Immunoproteasome in oxidative stress, aging, and disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 51, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnsburg, K.; Kirstein-Miles, J. Interrelation between protein synthesis, proteostasis and life span. Curr. Genom. 2014, 15, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, S.; Srpan, K.; Lin, W.; Lee, M.; Delconte, R.B.; Owyong, M.; Carmeliet, P.; Davis, D.M.; Xavier, J.B.; Hsu, K.C.; et al. Fatty acid oxidation fuels natural killer cell responses against infection and cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2319254121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Kong, X.; Feng, Z.; Anthony, T.G.; Watford, M.; Hou, Y.; Wu, G.; et al. The role of leucine and its metabolites in protein and energy metabolism. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Healthy Donors (n = 21) | Septic Patients (n = 37) | HLH Patients (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 10 females 11 males | 21 females 16 males | 11 females 4 males |

| Median age (in years) | 6.54 | 3.66 | 2.92 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Prematurity | 2/37 | ||

| Neurological disease | 4/37 | 2/15 | |

| Heart disease | 3/37 | ||

| Chronic respiratory failure | 3/37 | 1/15 | |

| HIV | 1/15 | ||

| Chronic renal failure | |||

| Organ dysfunction at diagnosis | |||

| Renal failure | 7/37 | 3/15 | |

| Respiratory failure | 10/37 | 7/15 | |

| Coagulopathy | 6/37 | 6/15 | |

| Liver failure | 3/37 | 11/15 | |

| Heart failure | 34/37 | 1/15 | |

| Neurological failure | 4/37 | 2/15 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 3/37 | 1/15 |

| Cluster | Biological Process GO Term | FDR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLH vs. HD | HLH vs. Sepsis | ||

| 1 | Proteasomal ubiquitin-independent protein catabolic process (GO:0010499) | 7.16 × 10−16 | 1.08 × 10−14 |

| Regulation of cellular amino acid metabolic process (GO:0006521) | 6.04 × 10−26 | 1.08 × 10−22 | |

| 2 | SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane (GO:0006614) | 1.08 × 10−14 | 8.79 × 10−17 |

| Translational initiation (GO:0006413) | 1.38 × 10−15 | 1.46 × 10−17 | |

| 3 | Fatty acid beta oxidation using acyl-CoA oxidase (GO:0033540) | 1.16 × 10−7 | 5.28 × 10−5 |

| Protein targeting to peroxisome (GO:0006625) | 2.22 × 10−9 | 10−6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martin-Pestana, D.; Azkargorta, M.; Pilar-Orive, F.J.; Redondo, S.; Urrutia, J.; Calvo, C.; Elortza, F.; Astigarraga, I.; Garcia-Obregon, S. Proteomics Reveals Differential Diagnosis Biomarkers Between Sepsis and Hemophagocytic Syndrome. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123113

Martin-Pestana D, Azkargorta M, Pilar-Orive FJ, Redondo S, Urrutia J, Calvo C, Elortza F, Astigarraga I, Garcia-Obregon S. Proteomics Reveals Differential Diagnosis Biomarkers Between Sepsis and Hemophagocytic Syndrome. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123113

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartin-Pestana, David, Mikel Azkargorta, Francisco Javier Pilar-Orive, Silvia Redondo, Janire Urrutia, Cristina Calvo, Felix Elortza, Itziar Astigarraga, and Susana Garcia-Obregon. 2025. "Proteomics Reveals Differential Diagnosis Biomarkers Between Sepsis and Hemophagocytic Syndrome" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123113

APA StyleMartin-Pestana, D., Azkargorta, M., Pilar-Orive, F. J., Redondo, S., Urrutia, J., Calvo, C., Elortza, F., Astigarraga, I., & Garcia-Obregon, S. (2025). Proteomics Reveals Differential Diagnosis Biomarkers Between Sepsis and Hemophagocytic Syndrome. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3113. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123113