Amyloid Protein-Induced Remodeling of Morphometry and Nanomechanics in Human Platelets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Aβ42 Peptides and α-Syn Samples

2.3. PLT Isolation and Sample Preparation for AFM Experiments

2.4. AFM Images

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphological Profile of Platelets Interacting with Amyloid Aβ42

3.2. Nanomechanical Properties of Amyloid Aβ42-Treated Platelets

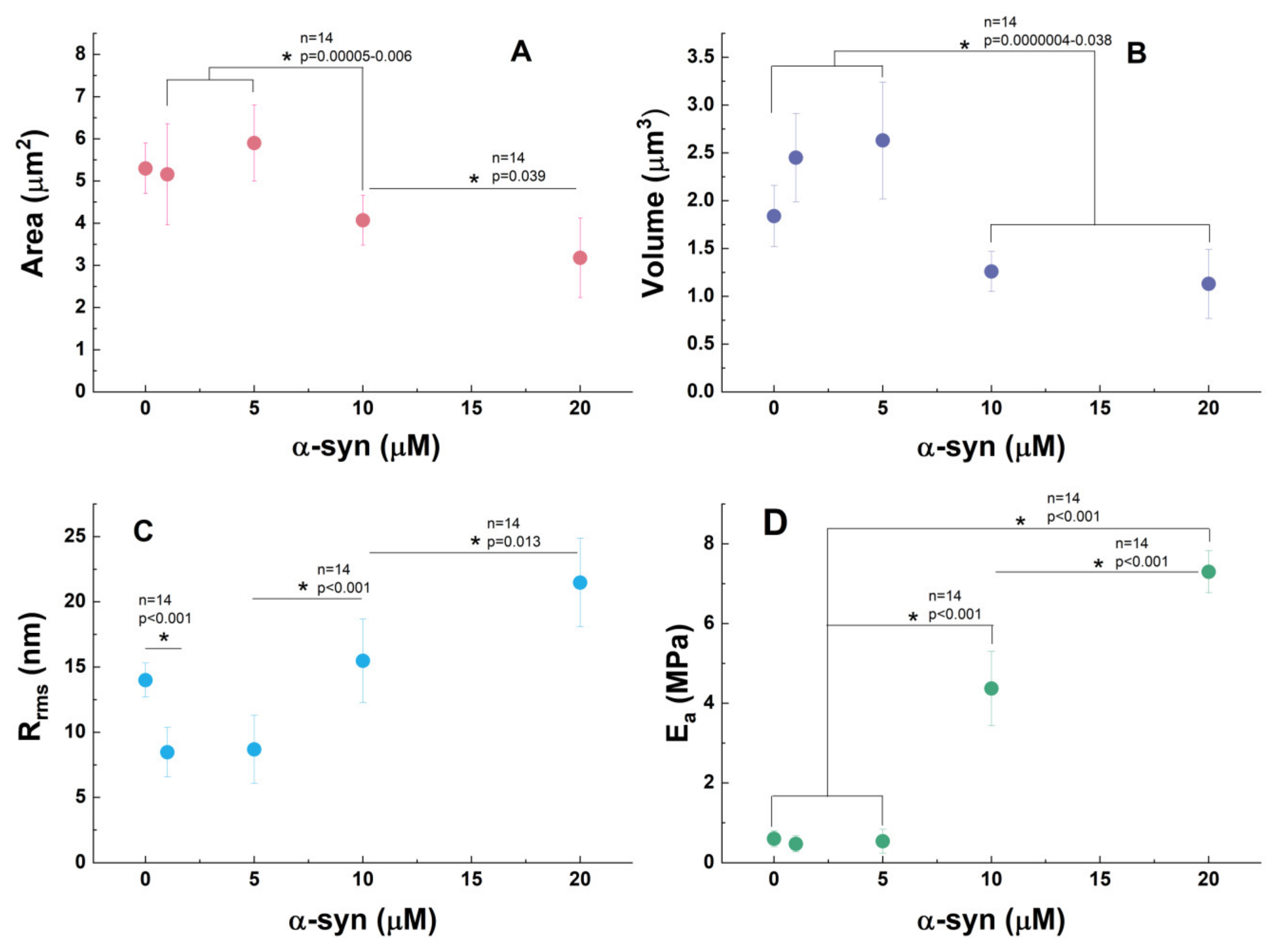

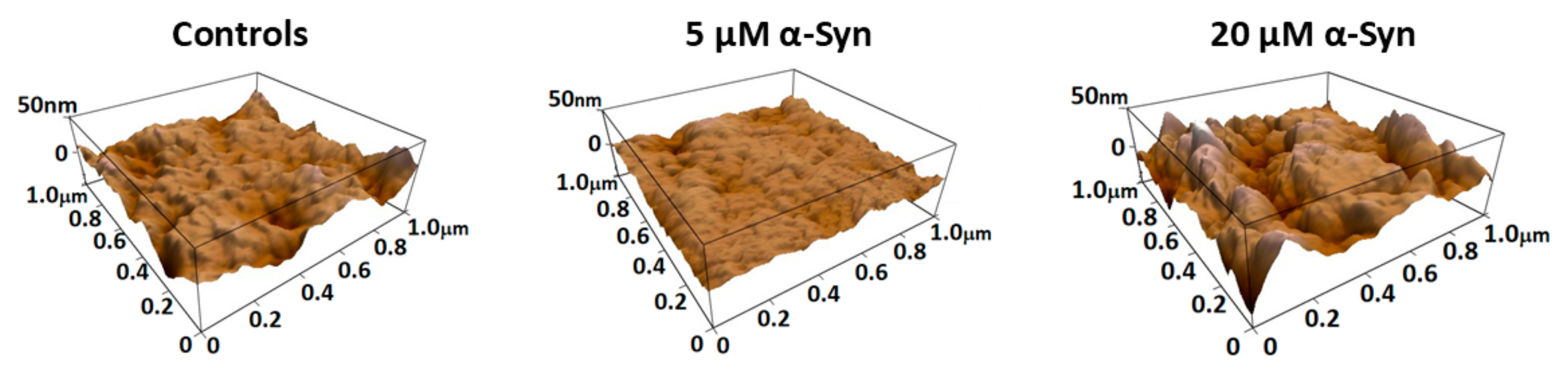

3.3. α-Synuclein Modifies PLT Morphometry and Nanomechanics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wojsiat, J.; Prandelli, C.; Laskowska-Kaszub, K.; Martín-Requero, A.; Wojda, U. Oxidative Stress and Aberrant Cell Cycle in Alzheimer’s Disease Lymphocytes: Diagnostic Prospects. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 46, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomelli, C.; Daniele, S.; Martini, C. Potential biomarkers and novel pharmacological targets in protein aggregation-related neurodegenerative diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 131, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolotti, A. Importance of the subcellular location of protein deposits in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 51, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiti, F.; Dobson, C.M. Protein Misfolding, Amyloid Formation, and Human Disease: A Summary of Progress Over the Last Decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.B.; Chaggar, P.; Kuhl, E.; Goriely, A. Protein-protein interactions in neurodegenerative diseases: A conspiracy theory. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldolesi, J. News about the Role of Fluid and Imaging Biomarkers in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiko, T.; Nakagawa, K.; Satoh, A.; Tsuduki, T.; Furukawa, K.; Arai, H.; Miyazawa, T. Amyloid levels in human red blood cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.D.; Binzer, M.; Stenager, E.; Gramsbergen, J.B. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2017, 135, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacci, F.; Daniele, S.; Piccarducci, R.; Giampietri, L.; Pietrobono, D.; Giorgi, F.S.; Nicoletti, V.; Frosini, D.; Libertini, P.; Lo Gerfo, A.; et al. Potential Diagnostic Value of Red Blood Cells α-Synuclein Heteroaggregates in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 6451–6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, A.B.; Beker, N.; Hulsman, M.; Sikkes, S.; Bank, N.B.; Scheltens, P.; Smit, A.B.; Rozemuller, A.J.; Hoozemans, J.J.; Holstege, H. Neuropathology and cognitive performance in self-reported cognitively healthy centenarians. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azargoonjahromi, A. The duality of amyloid-β: Its role in normal and Alzheimer’s disease states. Mol. Brain 2024, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Lendel, C. Extracellular protein components of amyloid plaques and their roles in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, A.; Lippa, C.F.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Lewy bodies in the amygdala: Increase of α-synuclein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases with tau-based inclusions. Arch. Neurol. 2004, 61, 1915–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozansoy, M.; Basak, A.N. The central theme of Parkinson’s disease: α-synuclein. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 47, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puspita, L.; Chung, S.Y.; Shim, J.-W. Oxidative stress and cellular pathologies in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Brain 2017, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brás, I.C.; Xylaki, M.; Outeiro, T.F. Mechanisms of alpha-synuclein toxicity: An update and outlook. Prog. Brain Res. 2020, 252, 91–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Chen, F.; Han, Z.; Yin, Z.; Ge, X.; Lei, P. Relationship Between Amyloid-β Deposition and Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021, 15, 69547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbarelli, A.; Lonati, E.; Brambilla, A.; Orlando, A.; Cazzaniga, E.; Piazza, F.; Ferrarese, C.; Masserini, M.; Sancini, G. Aβ42 production in brain capillary endothelial cells after oxygen and glucose deprivation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2012, 49, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wong, L.-W.; Su, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, N.; Chen, H.; Yi, C. Blood-brain barrier integrity in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 59, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.G.; Pagni, G.; Tagliarini, C.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Pomara, N. Can platelet activation result in increased plasma Aβ levels and contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease? Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Inestrosa, N.C.; Ross, G.S.; Fernandez, H.L. Platelets are the primary source of amyloid beta-peptide in human blood. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 213, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donner, L.; Fälker, K.; Gremer, L.; Klinker, S.; Pagani, G.; Ljungberg, L.U.; Lothmann, K.; Rizzi, F.; Schaller, M.; Gohlke, H.; et al. Platelets contribute to amyloid-β aggregation in cerebral vessels through integrin αIIbβ3–induced outside-in signaling and clusterin release. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giedraitis, V.; Sundelöf, J.; Irizarry, M.C.; Gårevik, N.; Hyman, B.T.; Wahlund, L.O.; Ingelsson, M.; Lannfelt, L. The normal equilibrium between CSF and plasma amyloid beta levels is disrupted in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2007, 427, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Grijalba, V.; Arbizu, J.; Romero, J.; Prieto, E.; Pesini, P.; Sarasa, L.; Guillen, F.; Monleón, I.; San-José, I.; Martínez-Lage, P.; et al. Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio alone or combined with FDG-PET can accurately predict amyloid-PET positivity: A cross-sectional analysis from the AB255 Study. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2019, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, L.; Liu, J.; Dang, L.; Wei, S.; Hu, N.; Gao, Y.; Peng, W.; Shang, S.; Huo, K.; et al. The Association of Plasma Amyloid-β and Cognitive Decline in Cognitively Unimpaired Population. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiao, F.; Shang, S.; Li, P.; Chen, C.; Dang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Huo, K.; Deng, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Elevation of Plasma Amyloid-β Level is More Significant in Early Stage of Cognitive Impairment: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulds, P.G.; Diggle, P.; Mitchell, J.D.; Parker, A.; Hasegawa, M.; Masuda-Suzukake, M.; Mann, D.M.; Allsop, D. A longitudinal study on α-synuclein in blood plasma as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Horng, H.E.; Yang, C.C.; Chieh, J.J.; Chen, H.H.; Liu, B.H.; Chiu, M.J. Plasma α-synuclein predicts cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2017, 88, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougea, A.; Stefanis, L.; Paraskevas, G.P.; Emmanouilidou, E.; Vekrelis, K.; Kapaki, E. Plasma α-synuclein levels in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, G.; Duan, Y.; Wang, F.; Lin, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, H.; Li, A.; Li, H. A Comparative Study of the Diagnostic Potential of Plasma and Erythrocytic α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 2019, 19, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Yang, S.-Y.; Yang, C.-C.; Chang, C.-W.; Wu, Y.-R. Plasma and Serum Alpha-Synuclein as a Biomarker of Diagnosis in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020, 10, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Pan, Y.T.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Yang, H.; Yu, S.-Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.H.; Wang, X.M. Systemic activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and plasma α-synuclein levels are correlated with motor severity and progression in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, A.S.L.; Tan, Y.J.; Yong, A.C.W.; Saffari, S.E.; Lu, Z.; Ng, E.Y.; Ng, S.Y.E.; Chia, N.S.Y.; Choi, X.; Heng, D.; et al. Utility of plasma Neurofilament light as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of the postural instability gait disorder motor subtype in early Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2020, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behari, M.; Shrivastava, M. Role of platelets in neurodegenerative diseases: A universal pathophysiology. Int. J. Neurosci. 2013, 123, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowert, N.S.; Donner, L.; Chatterjee, M.; Eisele, Y.S.; Towhid, S.T.; Münzer, P.; Walker, B.; Ogorek, I.; Borst, O.; Grandoch, M.; et al. Blood platelets in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitinger, M.; Varga, B.; Guterres, S.B.; Zellner, M. Platelets, a reliable source for peripheral Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers? Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, L.L.; Joaquim, H.P.; Forlenza, O.V. Platelet biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. World J. Psychiatry 2012, 2, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, R.; Ułamek-Kozioł, M. Lymphocytes, Platelets, Erythrocytes, and Exosomes as Possible Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Diagnosis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1118, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Italiano, J.E., Jr.; Richardson, J.L.; Patel-Hett, S.; Battinelli, E.; Zaslavsky, A.; Short, S.; Ryeom, S.; Folkman, J.; Klement, G.L. Angiogenesis is regulated by a novel mechanism: Pro- and antiangiogenic proteins are organized into separate platelet a-granules and differentially released. Blood 2008, 111, 1227–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perello, M.; Stuart, R.; Nillni, E.A. Prothyrotropin-releasing hormone targets its processing products to different vesicles of the secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 19936–19947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, A.I.; Martins, R.N.; Rumble, B.; Moir, R.; Fuller, S.; Milward, E.; Currie, J.; Ames, D.; Weidemann, A.; Fischer, P. The amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer’s disease is released by human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 15977–15983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndt, Q.X.; Li, M.C.; Bush, A.I.; Rumble, B.; Mackenzie, I.; Friedhuber, A.; Beyreuther, K.; Masters, C.L. Membrane-associated forms of the beta A4 amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease in human platelet and brain: Surface expression on the activated human platelet. Blood 1994, 84, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Catricala, S.; Torti, M.; Ricevuti, G. Alzheimer disease and platelets: How’s that relevant. Immun. Ageing 2012, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Raventos, P.; Beyer, K. Alternative platelet activation pathways and their role in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 159, 105512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nostrand, W.E.; Schmaier, A.H.; Farrow, J.S.; Cunningham, D.D. Protease nexin-II (amyloid beta-protein precursor): A platelet alpha-granule protein. Science 1990, 248, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Hynan, L.S.; Baskin, F.; Rosenberg, R.N. Platelet amyloid precursor protein processing: A bio-marker for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006, 240, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuner, D.; Eckman, C.; Jensen, M.; Song, X.; Citron, M.; Suzuki, N.; Bird, T.D.; Hardy, J.; Hutton, M.; Kukull, W.; et al. Secreted amyloid β–protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, L.; Elvers, M. Platelets and Neurodegenerative Diseases. In Platelets in Thrombotic and Non-Thrombotic Disorders; Gresele, P., Kleiman, N., Lopez, J., Page, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1209–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Di Luca, M.; Colciaghi, F.; Pastorino, L.; Borroni, B.; Padovani, A.; Cattabeni, F. Platelets as a peripheral district where to study pathogenetic mechanisms of alzheimer disease: The case of amyloid precursor protein. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 405, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.X.; Campbell, B.C.; McLean, C.A.; Thyagarajan, D.; Gai, W.P.; Kapsa, R.M.; Beyreuther, K.; Masters, C.L.; Culvenor, J.G. Platelet alpha- and gamma synucleins in Parkinson’s disease and normal control subjects. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2002, 4, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Agnaf, O.M.; Salem, S.A.; Paleologou, K.E.; Curran, M.D.; Gibson, M.J.; Court, J.A.; Schlossmacher, M.G.; Allsop, D. Detection of oligomeric forms of alpha synuclein protein in human plasma as a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R.; Kling, K.; Anderson, J.P.; Banducci, K.; Cole, T.; Diep, L.; Fox, M.; Goldstein, J.M.; Soriano, F.; Seubert, P.; et al. Red blood cells are the major source of alpha-synuclein in blood. Neurodegener. Dis. 2008, 5, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquasaliente, L.; Pontarollo, G.; Radu, C.M.; Peterle, D.; Artusi, I.; Pagotto, A.; Uliana, F.; Negro, A.; Simioni, P.; De Filippis, V. Exogenous human α-Synuclein acts in vitro as a mild platelet antiaggregant inhibiting α-thrombin-induced platelet activation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniuk, C.M.; Schlegelmilch, J.; Meyerson, H.J.; Harding, C.V.; Maitta, R.W. Initial assessment of α-synuclein structure in platelets. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2022, 53, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.J.; Sagara, Y.; Arroyo, A.; Rockenstein, E.; Sisk, A.; Mallory, M.; Wong, J.; Takenouchi, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Masliah, E. α-Synuclein promotes mitochondrial deficit and oxidative stress. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, P.C.; Kurzawa, M.; Blain, P.G.; Morris, C.M. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Dis. 2011, 2011, 716871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, M.; Das, T.K.; Behari, M.; Pati, U.; Vivekanandhan, S. Ultrastructural Variations in Platelets and Platelet Mitochondria: A Novel Feature in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2011, 35, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocer, A.; Yaman, A.; Niftaliyev, E.; Duruyen, H.; Eryilmaz, M.; Kocer, E. Assessment of platelet indices in patients with neurodegenerative diseases: Mean platelet volume was increased in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2013, 2013, 986254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Maitta, R.W. Alpha synuclein in hematopoiesis and immunity. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijkova, V.; Todinova, S.; Andreeva, T.; Langari, A.; Bogdanova, D.; Zlatareva, E.; Kalaydzhiev, N.; Milanov, I.; Taneva, S.G. Platelets’ Nanomechanics and Morphology in Neurodegenerative Pathologies. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneva, S.G.; Todinova, S.; Andreeva, T. Morphometric and Nanomechanical Screening of Peripheral Blood Cells with Atomic Force Microscopy for Label-Free Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, G.; Watanabe, C.; Puff, N.; Yordanova, V.; Seigneuret, M.; Angelova, M.I. Amyloid-β Interactions with Lipid Rafts in Biomimetic Systems: A Review of Laboratory Methods. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2187, 47–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, M.; Linse, S.; Nilsson, H.; Brundin, P.; Sparr, E. Membrane Interaction of α-Synuclein in Different Aggregation States. J. Park. Dis. 2011, 1, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robotta, M.; Gerding, H.R.; Vogel, A.; Hauser, K.; Schildknecht, S.; Karreman, C.; Leist, M.; Subramaniam, V.; Drescher, M. Alpha-Synuclein Binds to the Inner Membrane of Mitochondria in an α-Helical Conformation. Chembiochem 2014, 15, 2499–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagur, P.K.; McCoy, J.P., Jr. Collection, Storage, and Preparation of Human Blood Cells. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2015, 73, 5.1.1–5.1.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadelmawla, E.S.; Koura, M.M.; Macsoud, T.M.A.; Elewa, I.M.; Soliman, H.H. Roughness parameters. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 123, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girasole, M.; Dinarelli, S.; Boumis, G. Structure and function in native and pathological erythrocytes: A quantitative view from the nanoscale. Micron 2012, 43, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, I.N. The relation between load and penetration in the axisymmetric boussinesq problem for a punch of arbitrary profile. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1965, 3, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, J.H. The platelet: Form and function. Semin. Hematol. 2006, 43, S94–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlus, K.R.; Italiano, J.E., Jr. 2—Megakaryocyte Development and Platelet Formation. In Platelets, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.G. 3—The Structure of Resting and Activated Platelets. In Platelets, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bearer, E.L. Cytoskeletal Domains in the Activated Platelet. Cell Motil. Cytoskel. 1995, 30, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, S.; Conesa, J.J.; Cuervo, A.; Melero, R.; Martins, B.; Fernandez-Gimenez, E.; de Isidro-Gomez, F.P.; De la Morena, J.; Studt, J.D.; Sorzano, C.O.S.; et al. Structural analysis of receptors and actin polarity in platelet protrusions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2105004118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posch, S.; Neundlinger, I.; Leitner, M.; Siostrzonek, P.; Panzer, S.; Hinterdorfer, P.; Ebner, A. Activation induced morphological changes and integrin αIIbβ3 activity of living platelets. Methods 2013, 60, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachs, L.; Denker, C.; Greinacher, A.; Palankar, R. Quantifying single-platelet biomechanics: An outsider’s guide to biophysical methods and recent advances. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 4, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plooy, J.N.; Buys, A.; Duim, W.; Pretorius, E. Comparison of platelet ultrastructure and elastic properties in thrombo-embolic ischemic stroke and smoking using atomic force and scanning electron microscopy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.A.; Chaudhuri, O.; Crow, A.; Webster, K.D.; Li, T.D.; Kita, A.; Huang, J.; Fletcher, D.A. Mechanics and contraction dynamics of single platelets and implications for clot stiffening. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, T.; Komsa-Penkova, R.; Langari, A.; Krumova, S.; Golemanov, G.; Georgieva, G.B.; Taneva, S.G.; Giosheva, I.; Mihaylova, N.; Tchorbanov, A.; et al. Morphometric and nanomechanical features of platelets from women with early pregnancy loss provide new evidence of the impact of inherited thrombophilia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radmacher, M.; Fritz, M.; Kacher, C.M.; Cleveland, J.P.; Hansma, P.K. Measuring the viscoelastic properties of human platelets with the atomic force microscope. Biophys. J. 1996, 70, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, W.P. Platelet production, structure, and function. In Rodak’s Hematology, 6th ed.; Clinical Principles and Applications; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2020; pp. 136–153. [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Saenz, N.Z.; Serrano-Puente, A.; Gallegos-Flores, P.I.; Mendoza-Almanza, B.D.; Esparza-Ibarra, E.L.; Godina-González, S. Platelet Membrane: An Outstanding Factor in Cancer Metastasis. Membranes 2022, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Radmacher, M.; Gaub, H.E. Granula motion and membrane spreading during activation of human platelets imaged by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 1994, 66, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, D.L.; Troyer, M.D.; Nakamura, K.; Kubo, S.; Anthony, M.D.; Edwards, R.H. Lipid rafts mediate the synaptic localization of alpha-synuclein. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 6715–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Z.; Zhu, M.; Han, S.; Fink, A.L. GM1 specifically interacts with alpha-synuclein and inhibits fibrillation. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahyayauch, H.; Raab, M.; Busto, J.V.; Andraka, N.; Arrondo, J.R.; Masserini, M.; Tvaroska, I.; Goñi, F.M. Binding of β-amyloid (1-42) peptide to negatively charged phospholipid membranes in the liquid-ordered state: Modeling and experimental studies. Biophys. J. 2012, 103, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahyayauch, H.; de la Arada, I.; Masserini, M.E.; Arrondo, J.L.R.; Goñi, F.M.; Alonso, A. The Binding of Aβ42 Peptide Monomers to Sphingomyelin/Cholesterol/Ganglioside Bilayers Assayed by Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorahy, D.J.; Lincz, L.F.; Meldrum, C.J.; Burns, G.F. Biochemical isolation of a membrane microdomain from resting platelets highly enriched in the plasma membrane glycoprotein CD36. Biochem. J. 1996, 319, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, S.; Tronchère, H.; Payrastre, B. Lipid rafts are critical membrane domains in blood platelet activation processes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2003, 1610, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, E.; Ramlall, T.F.; Webb, W.W.; Eliezer, D. Quantification of α-synuclein binding to lipid vesicles using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 4692–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, A.S.; Chen, J.; Levine, R.L.; Bax, A. Site-Specific Interaction between α-Synuclein and Membranes Probed by NMR-Observed Methionine Oxidation Rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2943−2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, W.K.; De Simone, A.; Barritt, J.D.; Vendruscolo, M.; Dobson, C.M.; Fusco, G. A role of cholesterol in modulating the binding of a-synuclein to synaptic-like vesicles. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, S.; Camilleri, A.; Caruana, M.; Ruf, V.C.; Schmidt, F.; Leonov, A.; Ryazanov, S.; Griesinger, C.; Cauchi, R.J.; Kamp, F.; et al. Cardiolipin Promotes Pore-Forming Activity of Alpha-Synuclein Oligomers in Mitochondrial Membranes. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 3815–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, E.Y.; Frey, S.L.; Lee, K.Y.C. Ganglioside GM1-mediated amyloid beta fibrillogenesis and membrane disruption. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 1913–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefani, M.; Rigacci, S. Protein folding and aggregation into amyloid: The interference by natural phenolic compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 12411–12457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabik, D.; Chodaczek, G.; Kraszewskim, S. Effect of Amyloid-β Monomers on Lipid Membrane Mechanical Parameters-Potential Implications for Mechanically Driven Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herczenik, E.; Bouma, B.; Korporaal, S.J.; Strangi, R.; Zeng, Q.; Gros, P.; Van Eck, M.; Van Berkel, T.J.; Gebbink, M.F.; Akkerman, J.W.N. Activation of human platelets by misfolded proteins. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonkar, V.K.; Kulkarni, P.P.; Dash, D. Amyloid β peptide stimulates platelet activation through RhoA-dependent modulation of actomyosin organization. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canobbio, I.; Catricalà, S.; Di Pasqua, L.G.; Guidetti, G.; Consonni, A.; Manganaro, D.; Torti, M. Immobilized amyloid Aβ peptides support platelet adhesion and activation. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 2606–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elaskalani, O.; Khan, I.; Morici, M.; Matthysen, C.; Sabale, M.; Martins, R.N.; Verdile, G.; Metharom, P. Oligomeric and fibrillar amyloid beta 42 induce platelet aggregation partially through GPVI. Platelets 2018, 29, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, I.; Barrachina, M.N.; Hermida-Nogueira, L.; Casas, V.; Eble, J.A.; Carrascal, M.; Abián, J.; García, Á. Platelet membrane lipid rafts protein composition varies following GPVI and CLE receptors activation. J. Proteom. 2019, 195, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovskaya, I.D.; Aronova, M.A.; Kamykowski, J.A.; Prince, A.A.; Hoyne, J.D.; Calco, G.N.; Kuo, B.C.; He, Q.; Leapman, R.D.; Storrie, B. STEM tomography reveals that the canalicular system and α-granules remain separate compartments during early secretion stages in blood platelets. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, C.; Jia, W.; Khalil, J.S.; Hindle, M.S.; Coupland, C.; Calaminus, S.D.J.; Langer, J.D.; Frost, S.; Naseem, K.M.; Rivero, F.; et al. α-Synuclein Deletion Impairs Platelet Function: A Role for SNARE Complex Assembly. Cells 2024, 13, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, K.; Lee, M.; Morrell, C. Mechanism of Alpha-Synuclein Inhibition of Platelet Granule Exocytosis. Circulation 2007, 116, Abstract 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.N.; Joshi, S.; Chanzu, H.; Alfar, H.R.; Shravani Prakhya, K.; Whiteheart, S.W. α-Synuclein is the major platelet isoform but is dispensable for activation, secretion, and thrombosis. Platelets 2023, 34, 2267147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Jung, H.Y.; Kim, H.O.; Rhim, H.; Paik, S.R.; Chung, K.C.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J. Evidence that α-synuclein functions as a negative regulator of Ca-dependent α-granule release from human platelets. Blood 2002, 100, 2506–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, A.L. The aggregation and fibrillation of alpha-synuclein. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, E.R.; Rhoades, E. Effects of curvature and composition on α-synuclein binding to lipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pranke, I.M.; Morello, V.; Bigay, J.; Gibson, K.; Verbavatz, J.M.; Antonny, B.; Jackson, C.L. α-Synuclein and ALPS motifs are membrane curvature sensors whose contrasting chemistry mediates selective vesicle binding. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisi, N.; Feni, L.; Peqini, K.; Pérez-Peña, H.; Ongeri, S.; Pieraccini, S.; Pellegrino, S. α-Synuclein: An All-Inclusive Trip Around its Structure, Influencing Factors and Applied Techniques. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 666585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Li, J.; Souillac, P.; Millett, I.S.; Doniach, S.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M.; Fink, A.L. Biophysical properties of the synucleins and their propensities to fibrillate: Inhibition of alpha-synuclein assembly by beta- and gamma-synucleins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 11970–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliezer, D.; Kutluay, E.; Bussell, R., Jr.; Browne, G. Conformational properties of alpha-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 307, 1061–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, T.; Ahlstrom, L.S.; Leftin, A.; Kamp, F.; Haass, C.; Brown, M.F.; Beyer, K. The N-terminus of the intrinsically disordered protein α-synuclein triggers membrane binding and helix folding. Biophys. J. 2010, 99, 2116–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, O.V.; Nevzorova, T.A.; Mordakhanova, E.R.; Ponomareva, A.A.; Andrianova, I.A.; Le Minh, G.; Daminova, A.G.; Peshkova, A.D.; Alber, M.S.; Vagin, O.; et al. Fatal dysfunction and disintegration of thrombin-stimulated platelets. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 114; Chen, Z.; Tran, D.; Li, T.; Arias, K.; Griffith, B.P.; Wu, Z.J. The Role of a Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase Proteolysis and Mechanical Damage in Nonphysiological Shear Stress-Induced Platelet Receptor Shedding. ASAIO J. 2020, 66, 524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Visconte, C.; Canino, J.; Vismara, M.; Guidetti, G.F.; Raimondi, S.; Pula, G.; Torti, M.; Canobbio, I. Fibrillar amyloid peptides promote platelet aggregation through the coordinated action of ITAM- and ROS-dependent pathways. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 3029–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, I.; Baaten, C.C.F.M.J.; Jandrot-Perrus, M.; Gibbins, J.M.; Cate, T.H.; Heemskerk, J.W.M.; Jones, C.I.; van der Meijden, P.E.J. CoagulationFactor XIIIa and Activated Protein CActivate Platelets via GPVI and PAR1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzer, C.; Lassen, L.B.; Olsen, A.; Kofoed, R.H.; Reimer, L.; Gregersen, E.; Zheng, J.; Calì, T.; Gai, W.P.; Chen, T.; et al. Alpha-synuclein aggregates activate calcium pump SERCA leading to calcium dysregulation. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e44617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andreeva, T.D.; Todinova, S.; Langari, A.; Strijkova, V.; Katrova, V.; Taneva, S.G. Amyloid Protein-Induced Remodeling of Morphometry and Nanomechanics in Human Platelets. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123104

Andreeva TD, Todinova S, Langari A, Strijkova V, Katrova V, Taneva SG. Amyloid Protein-Induced Remodeling of Morphometry and Nanomechanics in Human Platelets. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123104

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndreeva, Tonya D., Svetla Todinova, Ariana Langari, Velichka Strijkova, Vesela Katrova, and Stefka G. Taneva. 2025. "Amyloid Protein-Induced Remodeling of Morphometry and Nanomechanics in Human Platelets" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123104

APA StyleAndreeva, T. D., Todinova, S., Langari, A., Strijkova, V., Katrova, V., & Taneva, S. G. (2025). Amyloid Protein-Induced Remodeling of Morphometry and Nanomechanics in Human Platelets. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123104