Obesity Promotes Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis Independent of Sex in SS Leptin Receptor Mutant (SSLepR) Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Groups

2.2. Metabolic Characterization of Female and Male SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats

2.3. Urinary Biochemical Assays

2.4. Renal Histopathology

2.5. Immunohistochemistry Studies (IHC)

2.6. Caspase-1 Activity Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

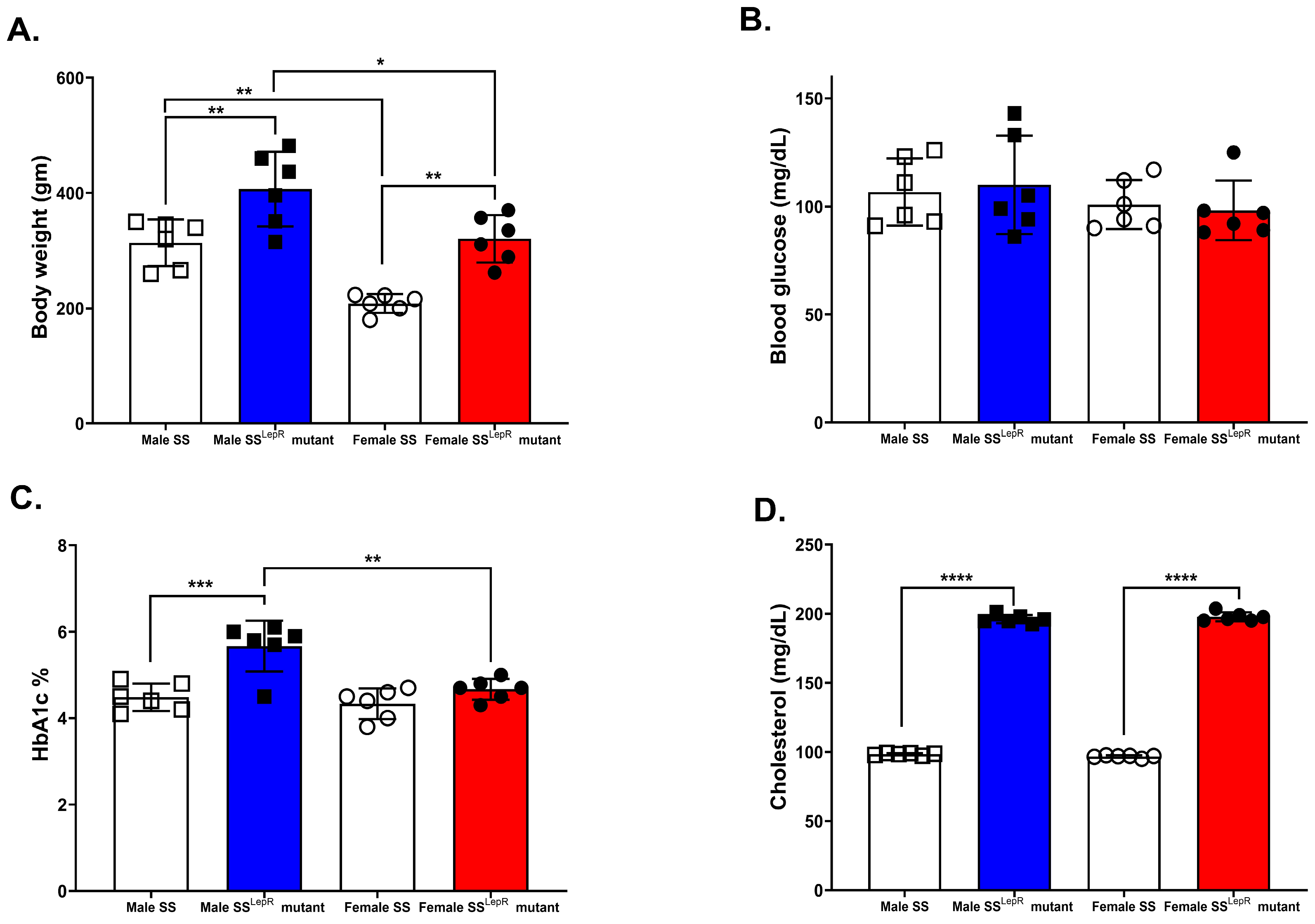

3.1. Body Weight, Blood Glucose, HbA1c, and Plasma Cholesterol in SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats in Both Sexes

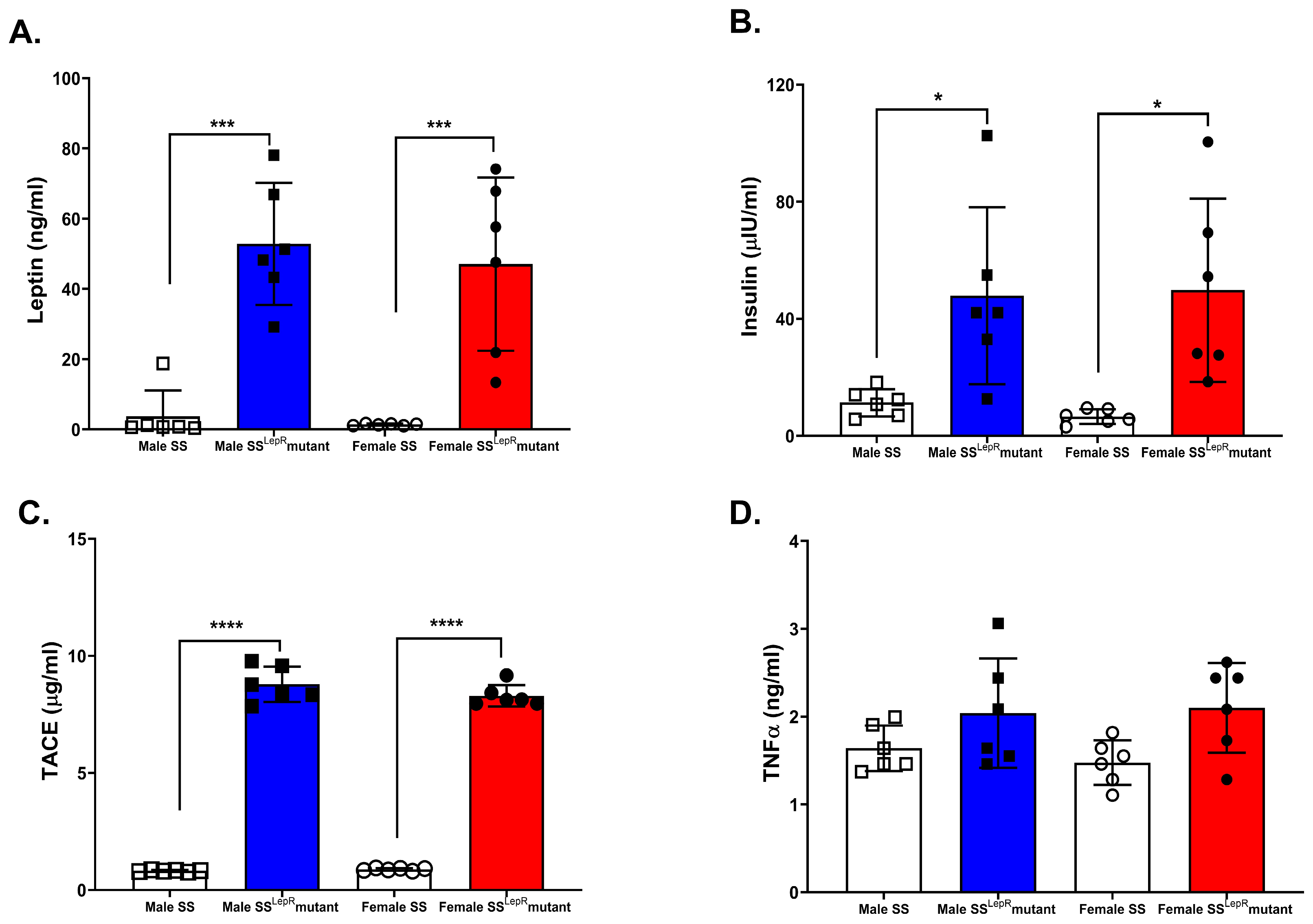

3.2. Plasma Leptin, Insulin, TACE, and TNF-α in SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats in Both Sexes

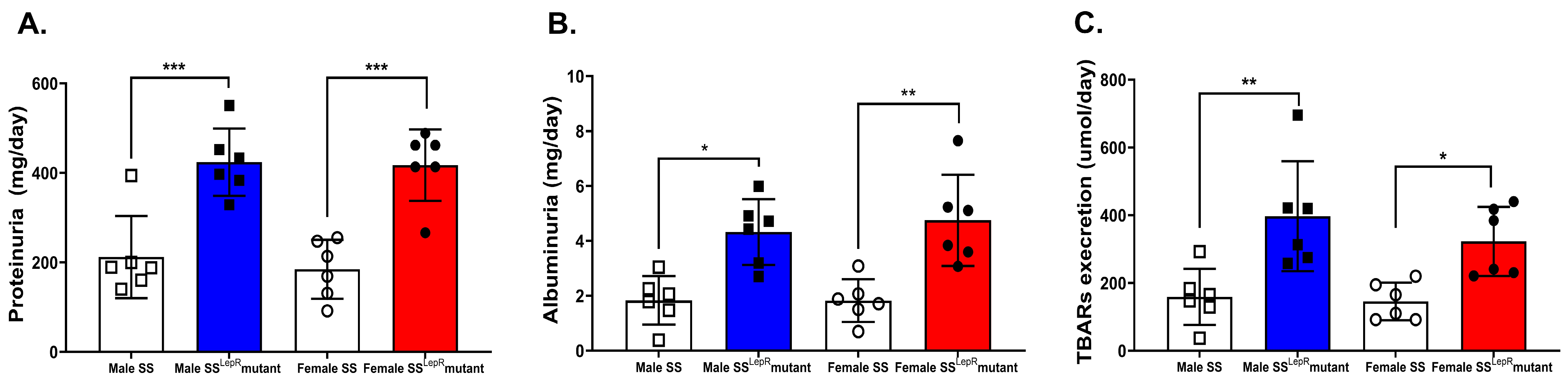

3.3. Total Proteinuria, Albuminuria, and Urinary TBARs in Male and Female SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats

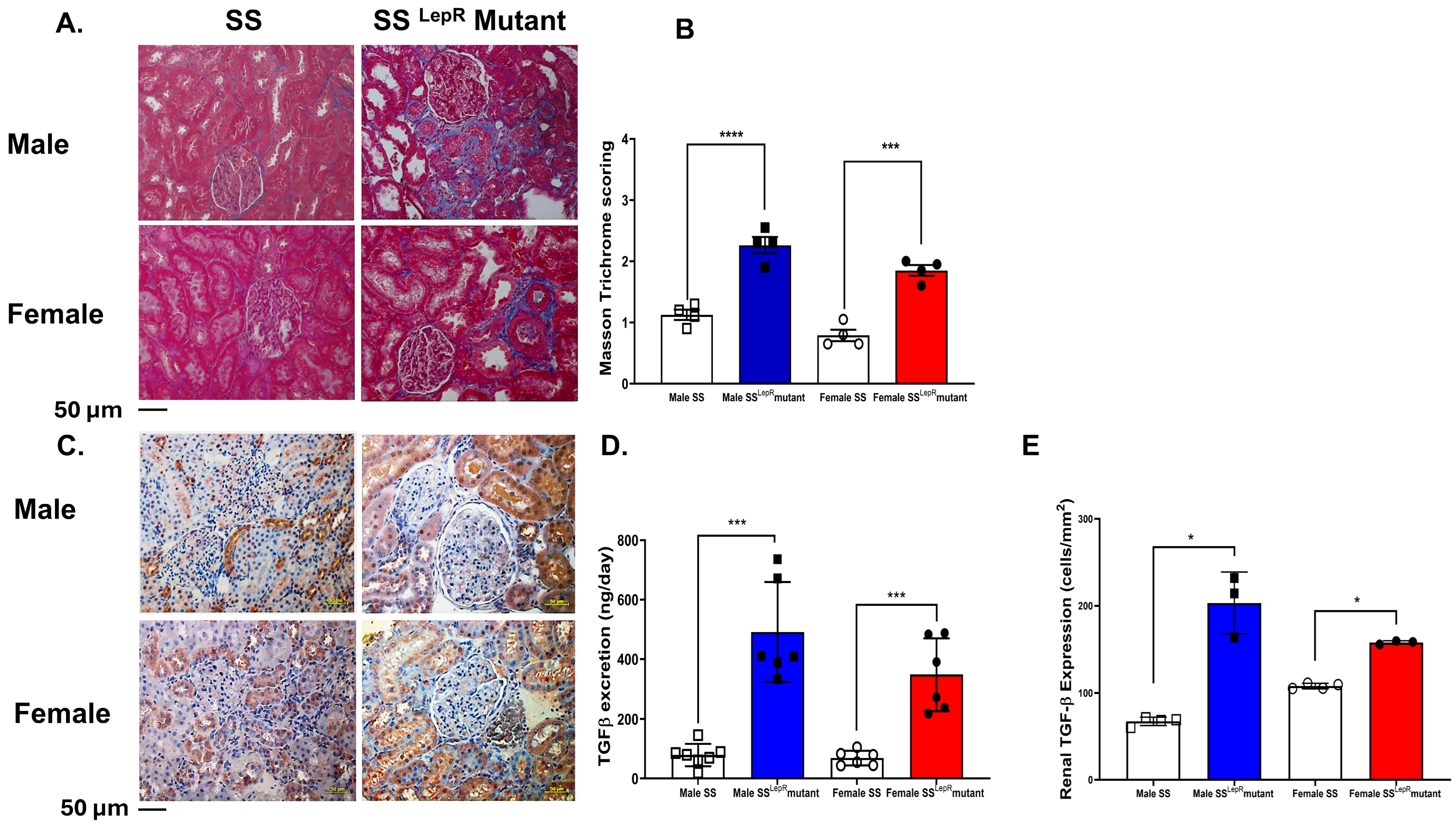

3.4. Masson Trichrome Scores and Renal TGF-β Expression in Male and Female SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats

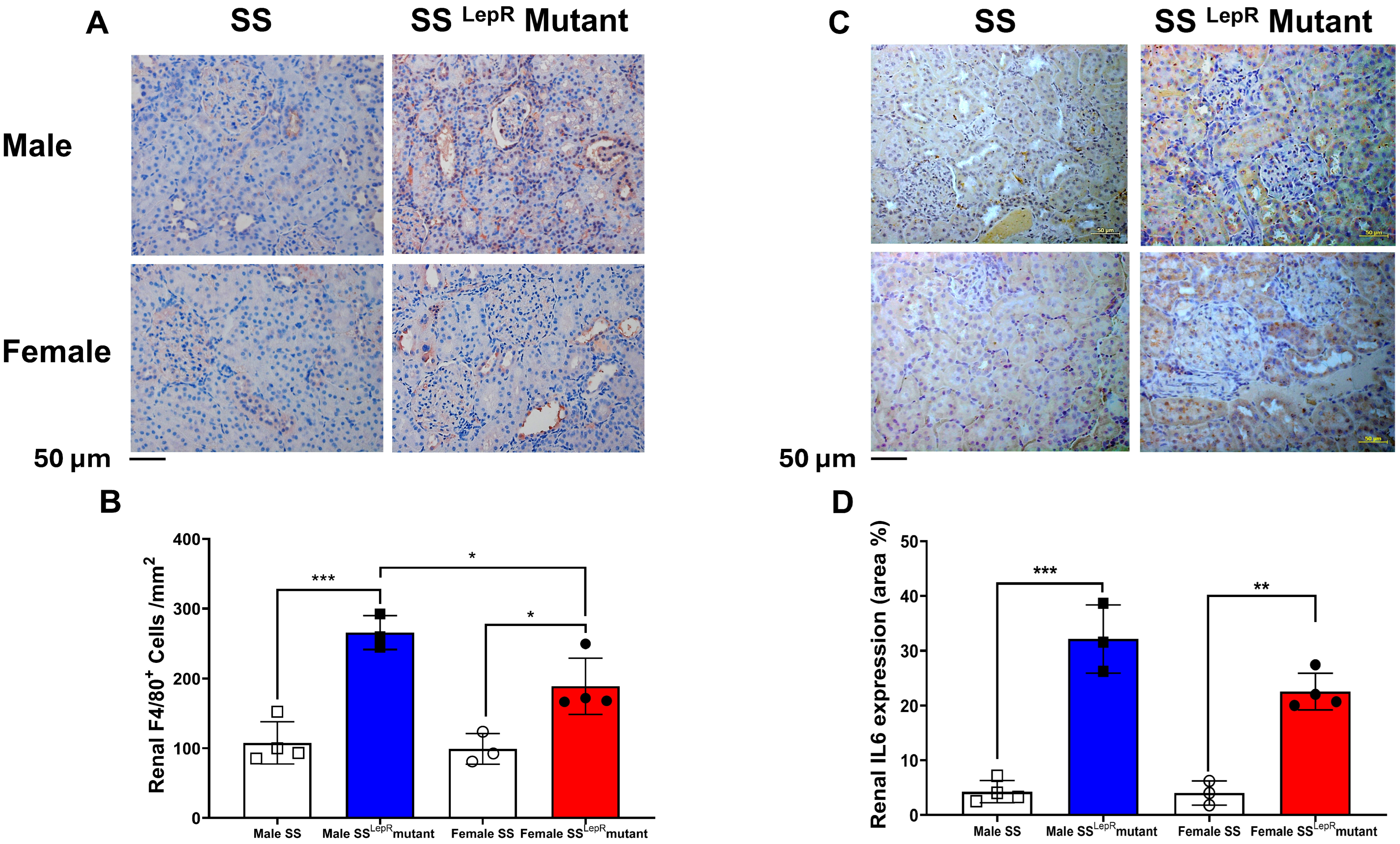

3.5. Renal F4/80, IL-6 Expression in Male and Female SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats

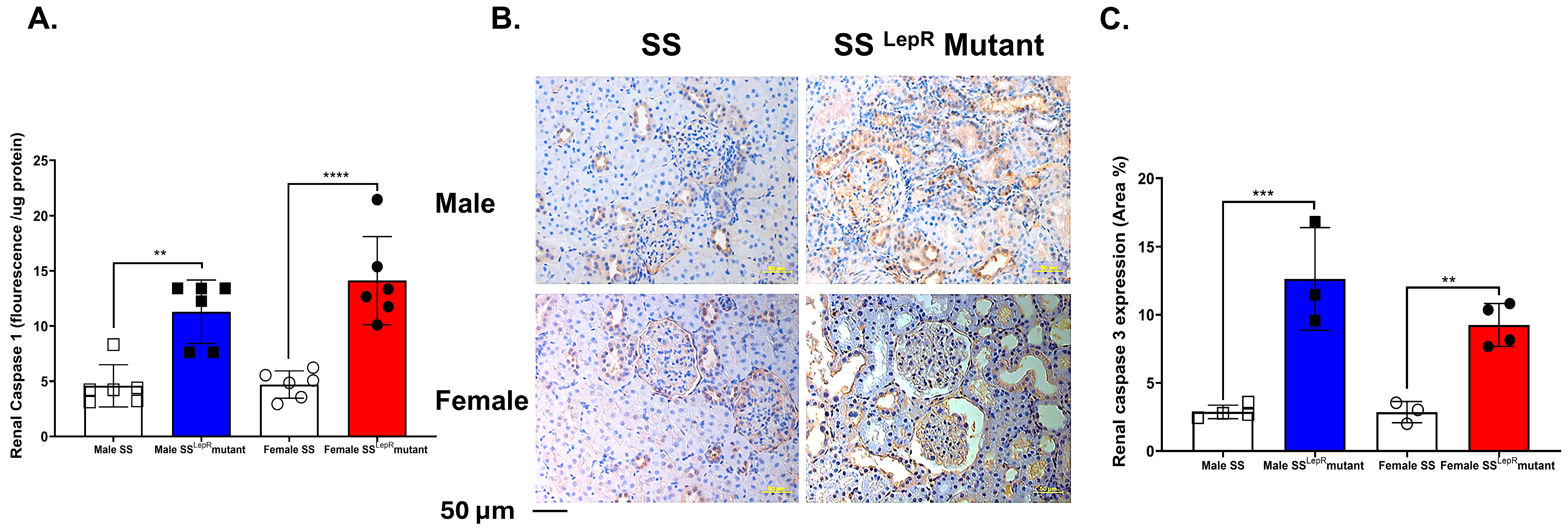

3.6. Renal Caspase-1 Activity and Caspase-3 Expression in SS and SSLepR Mutant Rats in Both Sexes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sweis, N.J. The economic burden of obesity in 2024: A cost analysis using the value of a statistical life. Crit. Public Health 2024, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Sultana, H.; Nazmul Hassan Refat, M.; Farhana, Z.; Abdulbasah Kamil, A.; Meshbahur Rahman, M. The global burden of overweight obesity and its association with economic status, benefiting from STEPs survey of WHO member states: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2024, 46, 102882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, G.; Boelsen-Robinson, T.; Hart, A.C.; Pesantes, M.A.; Sameeha, M.J.; Phulkerd, S.; Alsukait, R.F.; Thow, A.M. A comparative policy analysis of the adoption and implementation of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes (2016–2019) in 16 countries. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 543–564. [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, L.B. Weighing the Effect of Overweight/Obesity on Stroke Risk. Stroke 2024, 55, 1866–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-L.; Geukens, T.; Maetens, M.; Aparicio, S.; Bassez, A.; Borg, A.; Brock, J.; Broeks, A.; Caldas, C.; Cardoso, F.; et al. Obesity-associated changes in molecular biology of primary breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.Y.; Jin, E.H.; Chung, G.E.; Kim, Y.S.; Bae, J.H.; Yim, J.Y.; Han, K.-D.; Yang, S.Y. The risk of colorectal cancer according to obesity status at four-year intervals: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, C.; Chen, K.; Gu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Li, Q. Investigating the causal association between obesity and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and underlying mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boocock, M.; Naudé, Y.; Saywell, N.; Mawston, G. Obesity as a risk factor for musculoskeletal injury during manual handling tasks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 2024, 176, 106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.M.; Kaltsakas, G. Respiratory complications of obesity: From early changes to respiratory failure. Breathe 2023, 19, 220263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Sultana, R.; Greene, M.W. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, M.; Higashi, Y. Obesity and Endothelial Function. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weijie, Z.; Meng, Z.; Chunxiao, W.; Lingjie, M.; Anguo, Z.; Yan, Z.; Xinran, C.; Yanjiao, X.; Li, S. Obesity-induced chronic low-grade inflammation in adipose tissue: A pathway to Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Eagon, J.C.; Trujillo, M.E.; Scherer, P.E.; Klein, S. Visceral Fat Adipokine Secretion Is Associated with Systemic Inflammation in Obese Humans. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafili, K.; Kahl, S.; Mastrototaro, L.; Strassburger, K.; Pesta, D.; Herder, C.; Pützer, J.; Dewidar, B.; Hendlinger, M.; Granata, C.; et al. Mitochondrial respiration is decreased in visceral but not subcutaneous adipose tissue in obese individuals with fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1504–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, C.; Lu, F.; Liao, Y.; Cai, J.; Gao, J. Challenges and opportunities in obesity: The role of adipocytes during tissue fibrosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1365156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy-Matos, A.F.; Valério, C.M.; Júnior, W.S.S.; de Araujo-Neto, J.M.; Sposito, A.C.; Suassuna, J.H.R. CARDIAL-MS (CArdio-Renal-DIAbetes-Liver-Metabolic Syndrome): A new proposition for an integrated multisystem metabolic disease. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-G.; Kang, Y.-R.; Chang, Y.; Kim, J.; Sung, M.-K. Sex Disparities in Obesity: A Comprehensive Review of Hormonal and Genetic Influences on Obesity-Related Phenotypes. Obes. Rev. 2025, 30, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.M.; Salles, É.L.; Naeini, S.E.; Baban, B.; Abdelmageed, M.E.; Abdelaziz, R.R.; Suddek, G.M.; Elmarakby, A.A. Reno-protective effect of protocatechuic acid is independent of sex-related differences in murine model of UUO-induced kidney injury. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, S.-E.; Sung, M.-K. Sex and Gender Differences in Obesity: Biological, Sociocultural, and Clinical Perspectives. World J. Mens. Health 2025, 43, 758–772. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, B.; Shields, C.A.; Brown, A.K.; Ekperikpe, U.; Johnson, T.; Cornelius, D.C.; Williams, J.M. Depletion of macrophages slows the early progression of renal injury in obese Dahl salt-sensitive leptin receptor mutant rats. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2020, 318, F1489–F1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, B.; Shields, C.A.; Ekperikpe, U.S.; Brown, A.K.; Travis, O.K.; Maury, J.C.; Fitzgerald, S.; Smith, S.V.; Cornelius, D.C.; Williams, J.M. The SS(LepR) mutant rat represents a novel model to study obesity-induced renal injury before puberty. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2022, 322, R299–R308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, K.C.; Shields, C.A.; Poudel, B.; Fizer, B.; Pennington, A.; Szabo-Johnson, A.; Thompson, W.L.; Cornelius, D.C.; Williams, J.M. Impact of obesity as an independent risk factor for the development of renal injury: Implications from rat models of obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2019, 316, F316–F327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, H.; Che, R.; Zhang, A. Inflammasomes in the Pathophysiology of Kidney Diseases. Kidney Dis. 2015, 1, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.G.; Stratigou, T.; Voukali, M.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. The Kidney in Obesity: Current Evidence, Perspectives and Controversies. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 680–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, C.; Fan, Z.; Ding, X.; Tu, X.; Liu, Y. Associations between metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, abdominal obesity: A national retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozbek, L.; Abdel-Rahman, S.M.; Unlu, S.; Guldan, M.; Copur, S.; Burlacu, A.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. Exploring Adiposity and Chronic Kidney Disease: Clinical Implications, Management Strategies, Prognostic Considerations. Medicina 2024, 60, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scurt, F.G.; Ganz, M.J.; Herzog, C.; Bose, K.; Mertens, P.R.; Chatzikyrkou, C. Association of metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashim, A.; Capehart, K.; Tang, J.; Saad, K.M.; Abdelsayed, R.; Cooley, M.A.; Williams, J.M.; Elmarakby, A.A. Does Sex Matter in Obesity-Induced Periodontal Inflammation in the SSLepR Mutant Rats? Dent. J. 2025, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Mal, K.; Razaq, M.K.; Magsi, M.; Memon, M.K.; Memon, S.; Afroz, M.N.; Siddiqui, H.F.; Rizwan, A. Association of Leptin with Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Cureus 2020, 12, e12178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Zhang, D.; Lin, C.; He, H.; Xie, F.; Gan, L.; Fu, W.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y. TNF-alpha Antagonizes the Effect of Leptin on Insulin Secretion through FOXO1-Dependent Transcriptional Suppression of LepRb in INS-1 Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 9142798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.Y. Diverse roles of TGF-β/Smads in renal fibrosis and inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 7, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesmans, S.; Bouwknecht, J.A.; Ver Donck, L.; Langlois, X.; Acton, P.D.; De Haes, P.; Davoodi, N.; Meert, T.F.; Hellings, N.; Nuydens, R. Peripheral Administration of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Induces Neuroinflammation and Sickness but Not Depressive-Like Behavior in Mice. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 716920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Yan, H.; Zhuang, S. Inflammation and oxidative stress in obesity-related glomerulopathy. Int. J. Nephrol. 2012, 2012, 608397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Renal fibrosis: New insights into pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Yamamuro, D.; Wakabayashi, T.; Takei, A.; Takei, S.; Nagashima, S.; Okazaki, H.; Ebihara, K.; Yagyu, H.; Takayanagi, Y.; et al. Loss of myeloid lipoprotein lipase exacerbates adipose tissue fibrosis with collagen VI deposition and hyperlipidemia in leptin-deficient obese mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, P.; Luo, M. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: Recent advances in inflammatory mechanisms and related treatments. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2024, 115, 819–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Xu, M.; Chen, H.; Li, L.; Peng, T.; Zhao, K.; Zhuang, Y. Obesity-Related Glomerulopathy: From Mechanism to Therapeutic Target. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 4371–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Sheng, Z.; Yao, L. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: Pathogenesis, pathologic, clinical characteristics and treatment. Front. Med. 2017, 11, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kökény, G.; Calvier, L.; Hansmann, G. PPARγ and TGFβ—Major Regulators of Metabolism, Inflammation, and Fibrosis in the Lungs and Kidneys. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Tang, B.; Zhang, C. Signaling pathways of chronic kidney diseases, implications for therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; Mouton, A.J.; da Silva, A.A.; Omoto, A.C.M.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; do Carmo, J.M. Obesity, kidney dysfunction, and inflammation: Interactions in hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 117, 1859–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sánchez, A.; Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Bautista, M.; Esquivel-Soto, J.; Morales-González, Á.; Esquivel-Chirino, C.; Durante-Montiel, I.; Sánchez-Rivera, G.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Morales-González, J.A. Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 3117–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.E.; do Carmo, J.M.; da Silva, A.A.; Wang, Z.; Hall, M.E. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: Mechanistic links. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. Kidney Damage Caused by Obesity and Its Feasible Treatment Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castoldi, A.; Naffah de Souza, C.; Camara, N.O.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M. The Macrophage Switch in Obesity Development. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Hou, L. IL-6 and diabetic kidney disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1465625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; El Nahas, A.M.; Thomas, G.L.; Haylor, J.L.; Watson, P.F.; Wagner, B.; Johnson, T.S. Caspase-3 and apoptosis in experimental chronic renal scarring. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollberger, G.; Strittmatter, G.E.; Garstkiewicz, M.; Sand, J.; Beer, H.-D. Caspase-1: The inflammasome and beyond. Innate Immun. 2014, 20, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi, M.; Taghizadeh, S.; Kaviani, E.; Vakili, O.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; Tahamtan, M.; Savardashtaki, A. Caspase-3: Structure, function, and biotechnological aspects. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69, 1633–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.M.; Martinez, C.M.; de Jodar, C.; Reverte, V.; Bernabé, A.; Salazar, F.J.; Llinás, M.T. Gender differences in the renal changes induced by a prolonged high-fat diet in rats with altered renal development. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 77, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saad, K.M.; Gad, M.S.; Tang, J.; Capehart, K.; Abdelsayed, R.; Williams, J.M.; Elmarakby, A.A. Obesity Promotes Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis Independent of Sex in SS Leptin Receptor Mutant (SSLepR) Rats. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123105

Saad KM, Gad MS, Tang J, Capehart K, Abdelsayed R, Williams JM, Elmarakby AA. Obesity Promotes Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis Independent of Sex in SS Leptin Receptor Mutant (SSLepR) Rats. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123105

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaad, Karim M., Mohamed S. Gad, Jocelyn Tang, Kim Capehart, Rafik Abdelsayed, Jan M. Williams, and Ahmed A. Elmarakby. 2025. "Obesity Promotes Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis Independent of Sex in SS Leptin Receptor Mutant (SSLepR) Rats" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123105

APA StyleSaad, K. M., Gad, M. S., Tang, J., Capehart, K., Abdelsayed, R., Williams, J. M., & Elmarakby, A. A. (2025). Obesity Promotes Renal Inflammation and Fibrosis Independent of Sex in SS Leptin Receptor Mutant (SSLepR) Rats. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123105