Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) Drives Tumorigenicity in Small Cell Lung Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Strains, Tumor Induction, and Allografts Procedures

2.2. Cells Culture, Proliferation Assays, and Soft Agar Assay

2.3. Lentiviral Vectors, shRNA Constructs and Virus Production

2.4. Histology, Immunostaining, Immunoblotting, and X-Gal Staining

2.5. Protein Synthesis Assay

2.6. Gene Expression Data Analysis from Public Microarray Datasets

2.7. Survival Analysis of ASNS Amplification in TCGA PanCancer Atlas

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

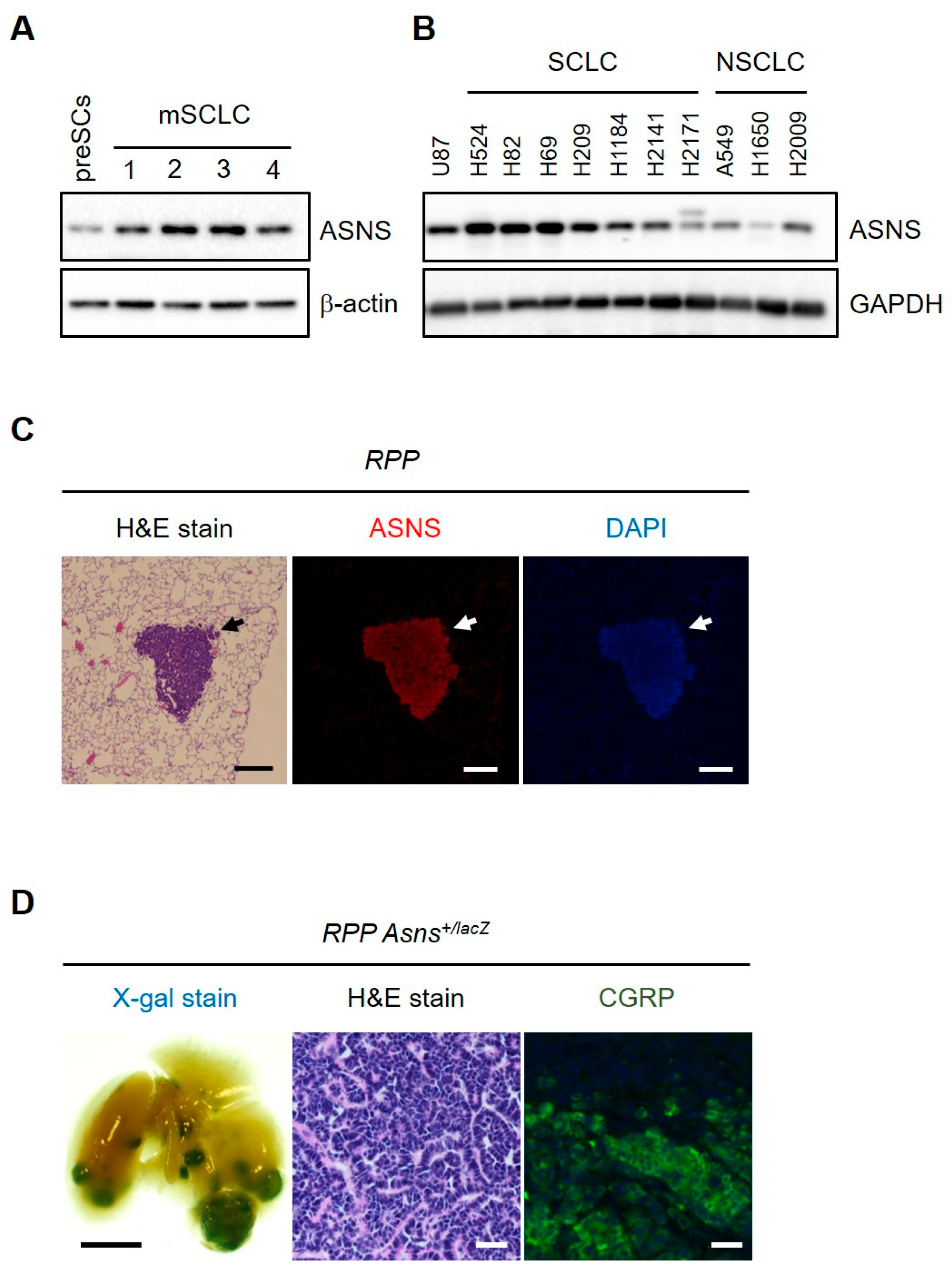

3.1. The Expression of ASNS Is Elevated in Small-Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC)

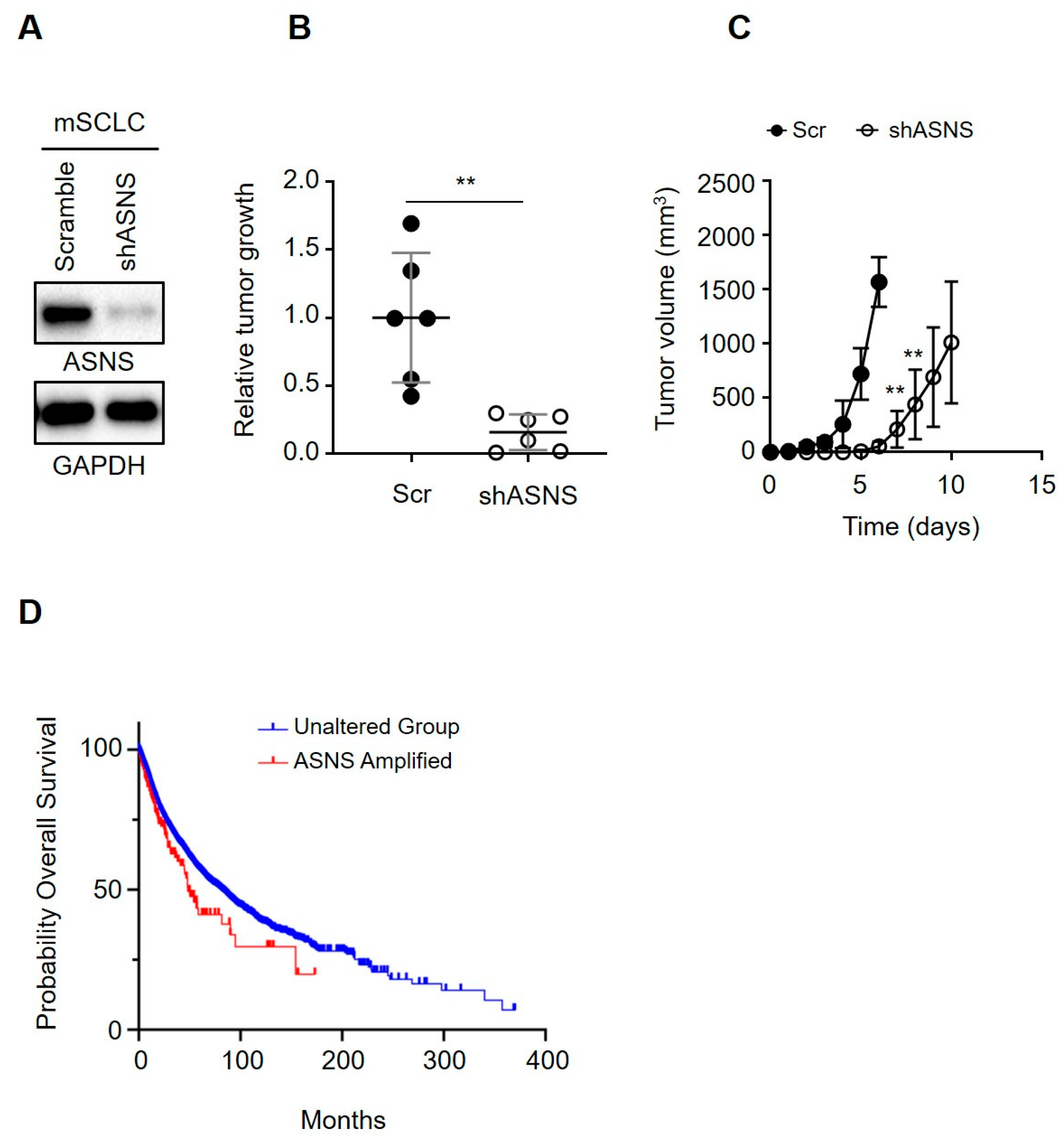

3.2. ASNS Is Required for SCLC Development

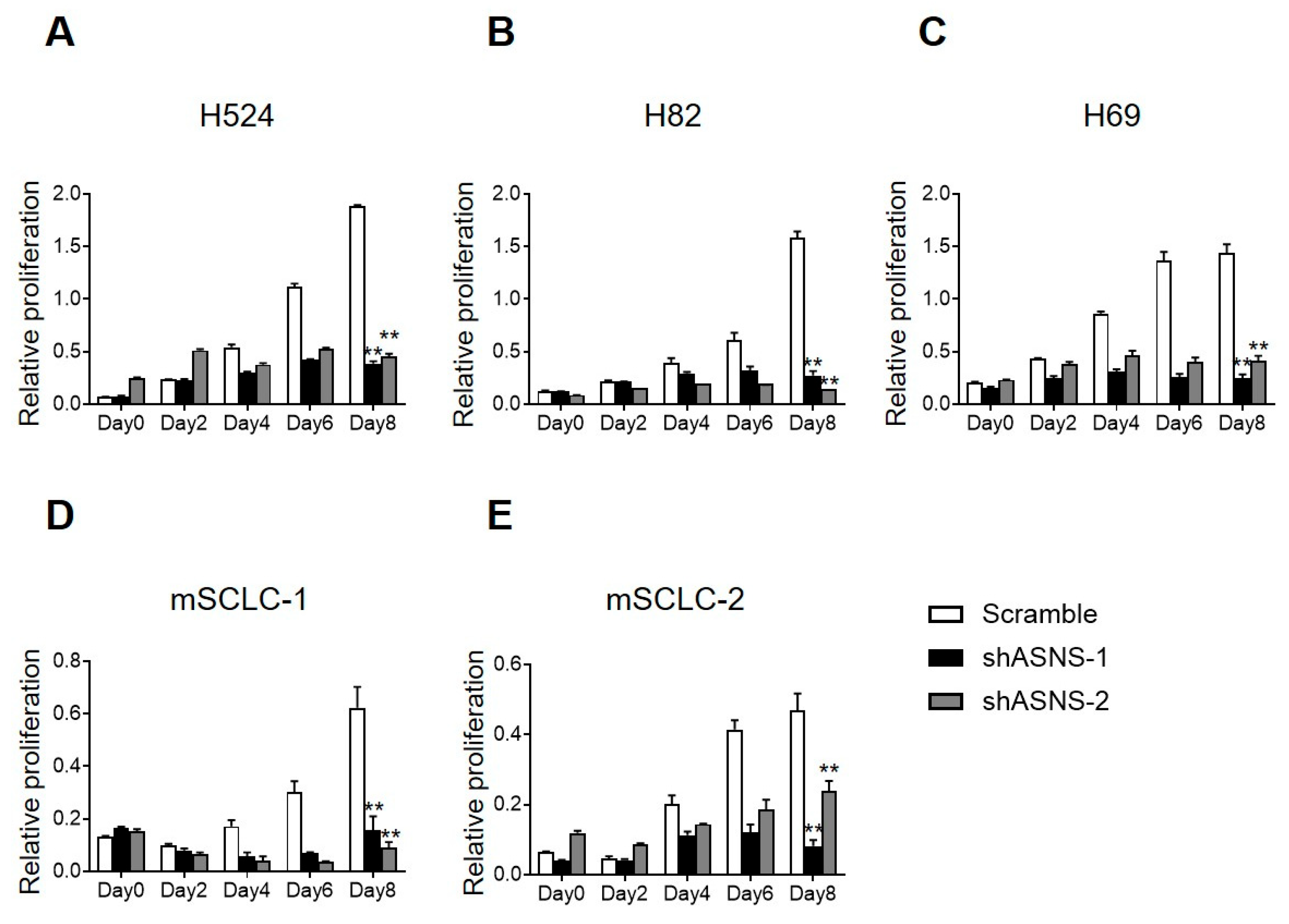

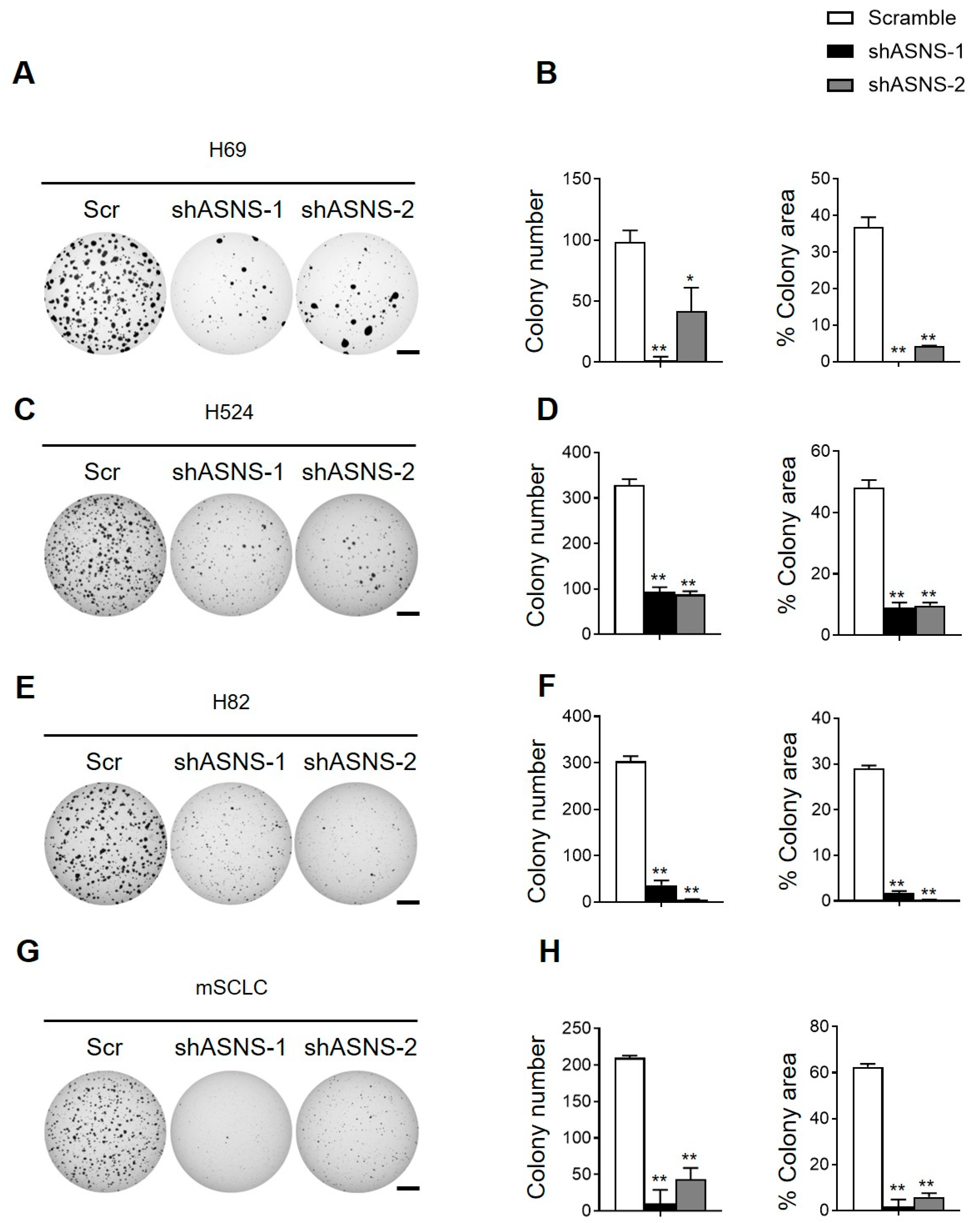

3.3. ASNS Promotes Tumorigenic Progression of Mouse and Human SCLC Cells

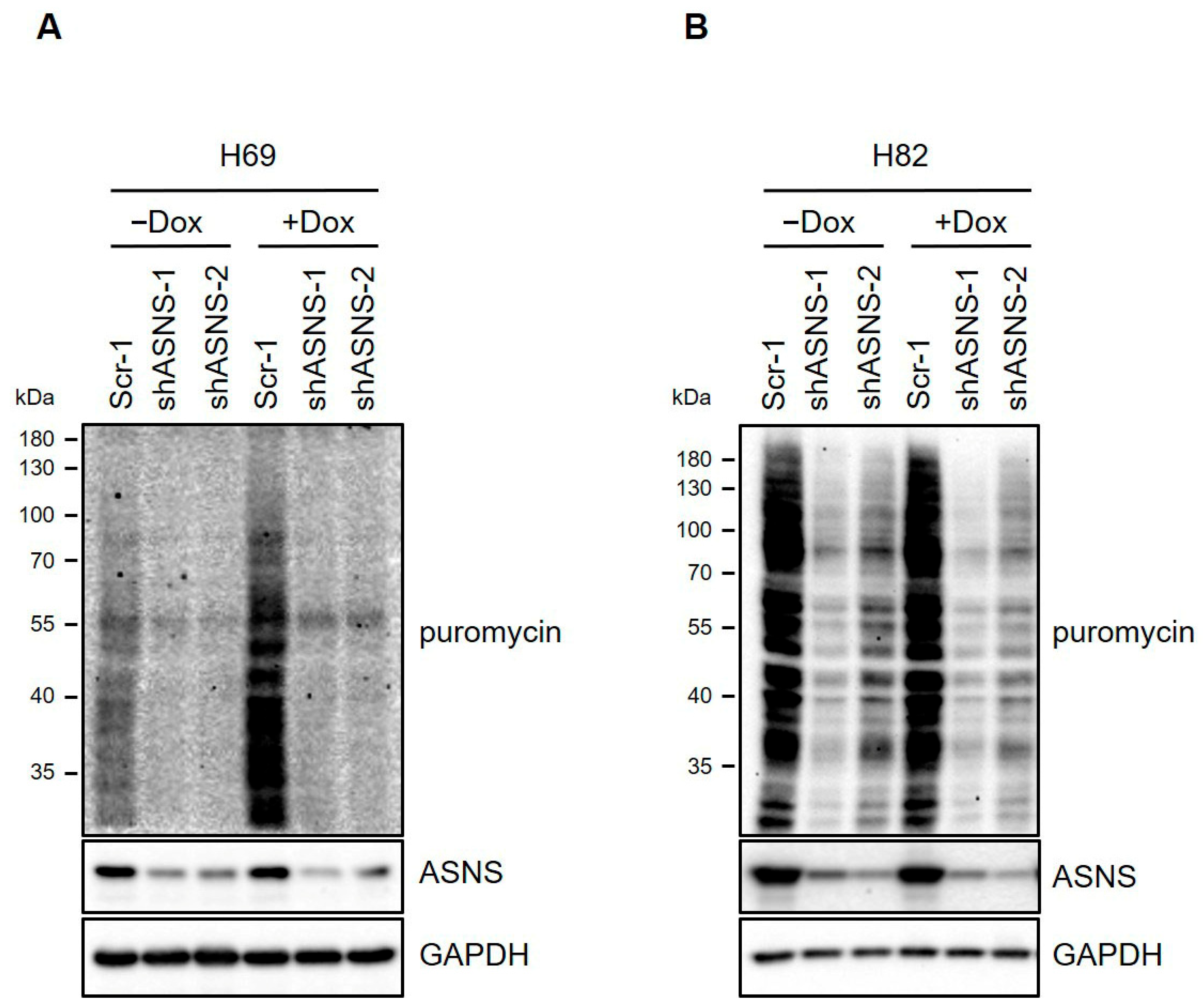

3.4. ASNS Is Required for SCLC Development and Cell Proliferation

3.5. Depletion of ASNS Reduces Ribosomal Transcription Programs in Human SCLC Cells

3.6. ASNS Drives Tumorigenic Progression of Mouse SCLC Cells

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gazdar, A.F.; Bunn, P.A.; Minna, J.D. Small-cell lung cancer: What we know, what we need to know and the path forward. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C.M.; Poirier, J.T.; Byers, L.A.; Dive, C.; Dowlati, A.; George, J.; Heymach, J.V.; Johnson, J.E.; Lehman, J.M.; MacPherson, D. Molecular subtypes of small cell lung cancer: A synthesis of human and mouse model data. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.; Ha, Y.; Lee, B.; Shin, J.; Rhim, T. Calnexin as a dual-role biomarker: Antibody-based diagnosis and therapeutic targeting in lung cancer. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.; Maas, L.; Abedpour, N.; Cartolano, M.; Kaiser, L.; Fischer, R.N.; Scheel, A.H.; Weber, J.-P.; Hellmich, M.; Bosco, G. Evolutionary trajectories of small cell lung cancer under therapy. Nature 2024, 627, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, M.; Chang, S.L.; Fishbane, N.; Davicioni, E.; Zhao, S.G.; Hartman, L.; Holmberg, E.; Feng, F.Y.; Speers, C.W.; Pierce, L.J. Clinicogenomic radiotherapy classifier predicting the need for intensified locoregional treatment after breast-conserving surgery for early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 3340–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, L.; Mansfield, A.S.; Szczęsna, A.; Havel, L.; Krzakowski, M.; Hochmair, M.J.; Huemer, F.; Losonczy, G.; Johnson, M.L.; Nishio, M. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2220–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, H.D.; Park, H.W. Emerging paradigms in cancer cell plasticity. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Lee, C.H. The contribution of the nervous system in the cancer progression. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, A.S.; Xu, S.; Graeber, T.G.; Braas, D.; Christofk, H.R. Asparagine promotes cancer cell proliferation through use as an amino acid exchange factor. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, S.R.; Wagenblast, E.; Khan, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Soto, M.; Wagner, M.; Turgeon, M.-O.; Fish, L.; Erard, N.; Gable, A.L. Asparagine bioavailability governs metastasis in a model of breast cancer. Nature 2018, 554, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Novoa, I.; Lu, P.D.; Calfon, M.; Sadri, N.; Yun, C.; Popko, B.; Paules, R. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilberg, M.S.; Shan, J.; Su, N. ATF4-dependent transcription mediates signaling of amino acid limitation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 20, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlova, N.N.; Hui, S.; Ghergurovich, J.M.; Fan, J.; Intlekofer, A.M.; White, R.M.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Thompson, C.B.; Zhang, J. As extracellular glutamine levels decline, asparagine becomes an essential amino acid. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 428–438. e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwinn, D.M.; Lee, A.G.; Briones-Martin-del-Campo, M.; Conn, C.S.; Simpson, D.R.; Scott, A.I.; Le, A.; Cowan, T.M.; Ruggero, D.; Sweet-Cordero, E.A. Oncogenic KRAS regulates amino acid homeostasis and asparagine biosynthesis via ATF4 and alters sensitivity to L-asparaginase. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 91–107. e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Gong, W.; Xiong, X.; Jia, X.; Xu, J. Asparagine: A key metabolic junction in targeted tumor therapy. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 206, 107292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, P.; Stazi, M.; Ballabio, C.; Margineanu, M.-B.; Li, Z.; Colón, C.I.; Hsieh, M.-S.; Pal Choudhuri, S.; Stastny, V.; Hamilton, S. Intrinsic electrical activity drives small-cell lung cancer progression. Nature 2025, 639, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.-J.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Bu, Y.; Li, L.; Deng, Y.-Z.; Sun, L.-Q.; Hu, C.-P.; Li, M. Asparagine synthetase regulates lung-cancer metastasis by stabilizing the β-catenin complex and modulating mitochondrial response. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, N.; He, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, M. Lung Cancer Cell-intrinsic Asparagine Synthetase Potentiates Anti-Tumor Immunity via Modulating Immunogenicity and Facilitating Immune Remodeling in Metastatic Tumor-draining Lymph Nodes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 6501–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Chu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, T.; Xu, M. Enhanced expression of asparagine synthetase under glucose-deprived conditions promotes esophageal squamous cell carcinoma development. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.; Taurino, G.; Bianchi, M.G.; Kilberg, M.S.; Bussolati, O. Asparagine synthetase in cancer: Beyond acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2020, 9, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, B.E.; Park, K.S.; Yiu, G.; Conklin, J.F.; Lin, C.; Burkhart, D.L.; Karnezis, A.N.; Sweet-Cordero, E.A.; Sage, J. Loss of p130 accelerates tumor development in a mouse model for human small-cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 3877–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPage, M.; Dooley, A.L.; Jacks, T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1064–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Wu, N.; Kim, Y.C.; Cheng, P.F.; Basom, R.; Kim, D.; Dunn, C.T.; Lee, A.Y.; Kim, K.; Lee, C.S.; et al. Genetic requirement for Mycl and efficacy of RNA Pol I inhibition in mouse models of small cell lung cancer. Genes. Dev. 2016, 30, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.M.; Miyaguchi, K.; Edwards, L.A.; Wang, H.; Wollebo, H.; Aiguo, L.; Murali, R.; Wang, Y.; Braas, D.; Michael, J.S.; et al. Elevated Asparagine Biosynthesis Drives Brain Tumor Stem Cell Metabolic Plasticity and Resistance to Oxidative Stress. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 1375–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Chung, Y.; Cheng, C.T.; Ouyang, C.; Fu, Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Chi, K.K.; Sadeghi, M.; Chu, P.; Kung, H.J.; et al. Autophagic reliance promotes metabolic reprogramming in oncogenic KRAS-driven tumorigenesis. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1481–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubert, B.; Solmonson, A.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science 2020, 368, eaaw5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, M.N.; Butterworth, E.A.; Kilberg, M.S. Asparagine synthetase: Regulation by cell stress and involvement in tumor biology. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E789–E799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Ding, L.; Yang, X.; Ding, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Hu, Q.; Ni, Y. Asparagine Synthetase-Mediated l-Asparagine Metabolism Disorder Promotes the Perineural Invasion of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 637226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, G.; Kawada, K.; Hanada, K.; Maekawa, H.; Itatani, Y.; Miyoshi, H.; Taketo, M.M.; Obama, K. Targeting Asparagine Synthetase in Tumorgenicity Using Patient-Derived Tumor-Initiating Cells. Cells 2022, 11, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzo, E.K.; Capo-Chichi, J.M.; Ben-Zeev, B.; Chitayat, D.; Mao, H.; Pappas, A.L.; Hitomi, Y.; Lu, Y.F.; Yao, X.; Hamdan, F.F.; et al. Deficiency of asparagine synthetase causes congenital microcephaly and a progressive form of encephalopathy. Neuron 2013, 80, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomelino, C.L.; Andring, J.T.; McKenna, R.; Kilberg, M.S. Asparagine synthetase: Function, structure, and role in disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 19952–19958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Gu, A.; Tang, N.; Zengin, G.; Li, M.Y.; Liu, Y. Patient-derived xenograft models in pan-cancer: From bench to clinic. Interdiscip. Med. 2025, 3, e20250016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Schalper, K.A.; Chiang, A. Mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance in small cell lung cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2024, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Sakai, K.; Hirano, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Hattori, A.; Dohmae, N.; Nishio, K.; Kakeya, H. Bisabosqual A: A novel asparagine synthetase inhibitor suppressing the proliferation and migration of human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 960, 176156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Jain, A.; Aladelokun, O.; Yan, H.; Gilbride, A.; Ferrucci, L.M.; Lu, L.; Khan, S.A.; Johnson, C.H. Asparagine, colorectal cancer, and the role of sex, genes, microbes, and diet: A narrative review. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 958666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Nambu, T.; Ebara, S.; Hasegawa, Y.; Toyoshima, K.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Tomita, D.; Fujimoto, J.; Kurasawa, O.; Takahara, C.; et al. Inhibition of GCN2 sensitizes ASNS-low cancer cells to asparaginase by disrupting the amino acid response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E7776–E7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, S.; Han, X.; Xiang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, T.; Tian, K.; Shen, K.; Yang, J.; Ma, X. Metabolic reprogramming in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutics. MedComm 2023, 4, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Kumanova, M.; Hart, L.S.; Sloane, K.; Zhang, H.; De Panis, D.N.; Bobrovnikova-Marjon, E.; Diehl, J.A.; Ron, D.; Koumenis, C. The GCN2-ATF4 pathway is critical for tumour cell survival and proliferation in response to nutrient deprivation. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 2082–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, K.; Kawada, K.; Obama, K. Targeting Asparagine Metabolism in Solid Tumors. Nutrients 2025, 17, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormerais, Y.; Massard, P.A.; Vucetic, M.; Giuliano, S.; Tambutté, E.; Durivault, J.; Vial, V.; Endou, H.; Wempe, M.F.; Parks, S.K. The glutamine transporter ASCT2 (SLC1A5) promotes tumor growth independently of the amino acid transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5). J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 2877–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Nagel, R.; Zaal, E.A.; Ugalde, A.P.; Han, R.; Proost, N.; Song, J.Y.; Pataskar, A.; Burylo, A.; Fu, H. SLC 1A3 contributes to L-asparaginase resistance in solid tumors. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwosu, Z.C.; Song, M.G.; di Magliano, M.P.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Kim, S.E. Nutrient transporters: Connecting cancer metabolism to therapeutic opportunities. Oncogene 2023, 42, 711–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.L.; Lu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Hu, C.; Lin, L.; Zhong, W. Expert consensus on treatment for stage III non-small cell lung cancer. Med. Adv. 2023, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargill, K.R.; Hasken, W.L.; Gay, C.M.; Byers, L.A. Alternative Energy: Breaking Down the Diverse Metabolic Features of Lung Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 757323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bermudez, J.; Williams, R.T.; Guarecuco, R.; Birsoy, K. Targeting extracellular nutrient dependencies of cancer cells. Mol. Metab. 2020, 33, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.A. Metabolic reprogramming of the tumor microenvironment to enhance immunotherapy. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solta, A.; Ernhofer, B.; Boettiger, K.; Lang, C.; Megyesfalvi, Z.; Mendrina, T.; Kirchhofer, D.; Timelthaler, G.; Szeitz, B.; Rezeli, M. Unveiling the powerhouse: ASCL1-driven small cell lung cancer is characterized by higher numbers of mitochondria and enhanced oxidative phosphorylation. Cancer Metab. 2025, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Dong, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, M.; Ding, Z.; Liu, L.; Jiang, T. Asparagine synthetase is an independent predictor of surgical survival and a potential therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Abdeljawaad, K.A.; Roshdy, E.; Mohamed, D.E.; Ali, T.F.; Gabr, G.A.; Jaragh-Alhadad, L.A.; Mekhemer, G.A.; Shawky, A.M.; Sidhom, P.A. In silico drug discovery of SIRT2 inhibitors from natural source as anticancer agents. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente, M.C.; Tamblay, N.; Herrada, J.; Maass, J.C. Prevalence and incidence of hearing loss in school-aged children in Santiago, Chile. Acta Oto-Laryngol 2025, 145, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastuzyn, E.D.; Day, C.E.; Kearns, R.B.; Kyrke-Smith, M.; Taibi, A.V.; McCormick, J.; Yoder, N.; Belnap, D.M.; Erlendsson, S.; Morado, D.R. The neuronal gene arc encodes a repurposed retrotransposon gag protein that mediates intercellular RNA transfer. Cell 2018, 172, 275–288.e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Han, P.; Li, X. Cemented versus cementless Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for the treatment of medial knee osteoarthritis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2024, 144, 4391–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karra, R.; Foglia, M.J.; Choi, W.-Y.; Belliveau, C.; DeBenedittis, P.; Poss, K.D. Vegfaa instructs cardiac muscle hyperplasia in adult zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8805–8810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, C.L.; Kennedy, D.A. What the reproductive number R0 can and cannot tell us about COVID-19 dynamics. Theor. Popul. Biol. 2021, 137, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joalland, B.; Shi, Y.; Patel, N.; Van Camp, R.; Suits, A.G. Dynamics of Cl+ propane, butanes revisited: A crossed beam slice imaging study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelschläger, H.A.; Buhl, E.H.; Dann, J.F. Development of the nervus terminalis in mammals including toothed whales and humans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987, 519, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathria, G.; Lee, J.S.; Hasnis, E.; Tandoc, K.; Scott, D.A.; Verma, S.; Feng, Y.; Larue, L.; Sahu, A.D.; Topisirovic, I. Translational reprogramming marks adaptation to asparagine restriction in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 1590–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, H.; Guo, D.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Chen, N.; Song, H.; Ji, X. Dual asparagine-depriving nanoparticles against solid tumors. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apfel, V.; Begue, D.; Cordo’, V.; Holzer, L.; Martinuzzi, L.; Buhles, A.; Kerr, G.; Barbosa, I.; Naumann, U.; Piquet, M. Therapeutic assessment of targeting ASNS combined with l-asparaginase treatment in solid tumors and investigation of resistance mechanisms. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieu, E.L.; Nguyen, T.; Rhyne, S.; Kim, J. Amino acids in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, M.; Kim, B.C.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, G.T.; Jang, S.-M.; Kim, K.-B. Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) Drives Tumorigenicity in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123087

Jeong M, Kim BC, Choi HJ, Lee GT, Jang S-M, Kim K-B. Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) Drives Tumorigenicity in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123087

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Minho, Beom Chang Kim, Hyoung Jin Choi, Gyu Tae Lee, Sang-Min Jang, and Kee-Beom Kim. 2025. "Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) Drives Tumorigenicity in Small Cell Lung Cancer" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123087

APA StyleJeong, M., Kim, B. C., Choi, H. J., Lee, G. T., Jang, S.-M., & Kim, K.-B. (2025). Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) Drives Tumorigenicity in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3087. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123087