Obesity Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Mortality and Readmission in Heart Failure Patients with Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Patients and Outcomes

2.3. Analysis Plan and Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.3. In-Hospital Outcomes

3.4. 1-Year Outcomes

3.5. Goodness of Fit and Calibration

4. Discussion

4.1. Obesity Paradox

4.2. Pathophysiology

4.3. Limitations

4.3.1. Selection Bias and Missing Parameters

4.3.2. COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. Strengths and Generalizability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFIB | Atrial fibrillation |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BP | Blood Pressure |

| CAD | Coronary Artery Disease |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| NRD | Nationwide Readmission Database |

| PVD | Peripheral Vascular disease |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| VFIB | Ventricular Fibrillation |

Appendix A

| Item No | Recommendation | Page No | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title and abstract | 1 | (a) Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | Pg. 1 2 |

| (b) Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was done and what was found | Pg. 1 | ||

| Introduction | |||

| Background/rationale | 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | Pg. 1 2 |

| Objectives | 3 | State specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | Pg. 2 |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Present key elements of study design early in the paper | Pg. 2 |

| Setting | 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | Pg. 2 |

| Participants | 6 | (a) Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants | Pg. 2 |

| Variables | 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | Pg. 2 3 |

| Data sources/measurement | 8 * | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | Pg. 2 3 |

| Bias | 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | NA |

| Study size | 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | NA |

| Quantitative variables | 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | Pg. 2 3 |

| Statistical methods | 12 | (a) Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | Pg. 2 3 |

| (b) Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | NA | ||

| (c) Explain how missing data were addressed | Pg. 2 3 | ||

| (d) If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | NA | ||

| (e) Describe any sensitivity analyses | Pg. 3 | ||

| Results | |||

| Participants | 13 * | (a) Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study—e.g., numbers potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, confirmed eligible, included in the study, completing follow-up, and analyzed | Pg. 3; Figure 1 |

| (b) Give reasons for non-participation at each stage | Pg. 3; Figure 1, Table A3 | ||

| (c) Consider use of a flow diagram | Pg. 3; Figure 1 | ||

| Descriptive data | 14 * | (a) Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, social) and information on exposures and potential confounders | Pg. 4; Table 1 |

| (b) Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | Pg. 3; Figure 1, Table A3 | ||

| Outcome data | 15 * | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures | Pg. 3 4 5 6; Table 1 and Table 2 |

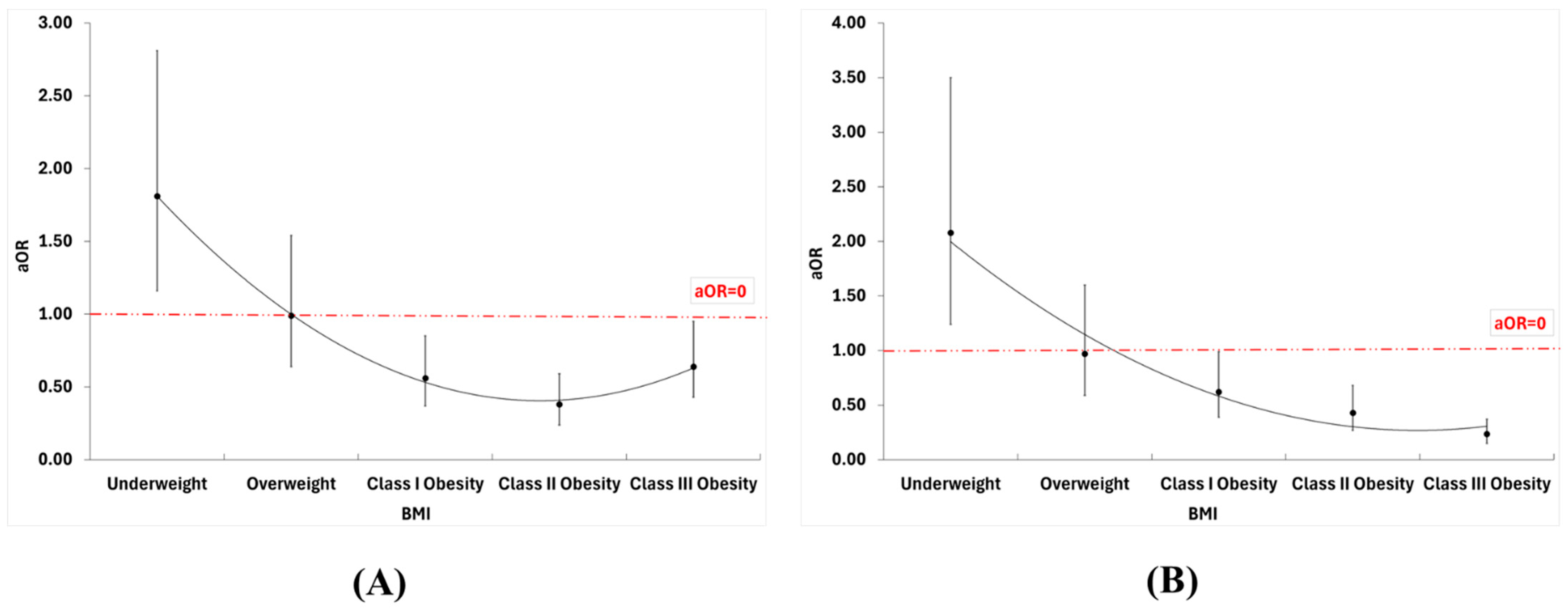

| Main results | 16 | (a) Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | Pg. 5 6; Table 2; Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4; Figure 2 and Figure 3 |

| (b) Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | Table 1 and Table 2; Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 | ||

| (c) If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | Pg. 6; Figure 3 | ||

| Other analyses | 17 | Report other analyses done—e.g., analyses of subgroups and interactions, and sensitivity analyses | Pg. 6; Figure A1 |

| Discussion | |||

| Key results | 18 | Summarize key results with reference to study objectives | Pg. 7 8 |

| Limitations | 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision. Discuss both direction and magnitude of any potential bias | Pg. 8 9 |

| Interpretation | 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | Pg. 7 8 9 |

| Generalizability | 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results | Pg. 9 |

| Other information | |||

| Funding | 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study and, if applicable, for the original study on which the present article is based | Pg. 10 |

| Variables | ICD-10 Codes |

|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | I480, I481, I482, I4891 |

| Acute renal failure | N170, N171, N172, N178, N179 |

| Body Mass Index | Underweight, [BMI] 19.9 or less: Z681 Normal Weight, [BMI] 20.0–24.9: Z6820, Z6821, Z6822, Z6823, Z6824 Overweight, [BMI] 25.0–29.9: Z6825, Z6826, Z6827, Z6828, Z6829 Class I Obesity, [BMI] 30.0–34.9: Z6830, Z6831, Z6832, Z6833, Z6834 Class II Obesity, [BMI] 35.0–39.9: Z6835, Z6836, Z6837, Z6838, Z6839 Class 3 Obesity, [BMI] 40 or greater: Z6840, Z6841, Z6842, Z6843, Z6844, Z6845 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | I2510, I2511, I252, I2582, I2584, Z955, Z951 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | N183, N184, N185, N186, N189, N19, Z4901, Z4902, Z9115, Z940, Z992, Z4931, Z4932 |

| Cardiogenic shock | R570 |

| Dyslipidemia | E785 |

| Heart Failure | I5020, I5021, I5022, I5023, I5030, I5031, I5032, I5033 |

| Hypertension | I10, I110, I119, I120, I129, I130, I1310, I1311, I132, I150, I151, I152, I158, I159, I674, O10011, O10012, O10013, O10019, O1002, O1003, O10111, O10112, O10113, O10119, O1012, O1013,O10211, O10212, O10213, O10219, O1022, O1023, O10311, O10312, O10313, O10319, O1032, O1033, O10411, O10412, O10413, O10419, O1042, O1043, O10911, O10912, O10913, O10919, O1092, O1093,O111, O112, O113, O119 |

| Peripheral Vascular disease | A5203, I050, I051, I052, I058, I059, I060, I061, I062, I068, I069, I070, I071, I072, I078, I079, I080, I081, I082, I083, I088, I089, I091, I0989, I340, I341, I342, I348, I349, I350, I351, I352, I358, I359, I360, I361, I362, I368, I369, I370, I371, I372, I378, I379, I38, I39, Q230, Q231, Q232, Q233, Z952, Z953, Z954 |

| Smoking | F17200, F17201, F17210, F17211, F17220, F17221, F17290, F17291, Z720, Z87891 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | E08x, E09x, E10x, E11x, E13x, O24.1x, O24.3x, O24.8, O24.9 |

| Ventricular Fibrillation | I4901 |

| BMI Data Available | Missing BMI Data | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26,199 (28.17%) | 66,803 (71.83%) | ||

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 66.05 (13.24) | 73.32 (12.44) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 12,463 (47.57) | 35,526 (53.18) | <0.001 |

| Income * | |||

| Low | 9128 (34.84) | 22,308 (33.39) | <0.001 |

| Low-middle | 7411 (28.29) | 18,043 (27.01) | |

| Middle-High | 5919 (22.59) | 15,592 (23.34) | |

| High | 3741 (14.28) | 10,860 (16.26) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| CAD | 11,352 (43.33) | 37,245 (55.75) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 19,691 (75.16) | 50,831 (76.09) | 0.003 |

| Smoking | 10,957 (41.82) | 25,800 (38.62) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 12,868 (49.12) | 33,157 (49.63) | 0.156 |

| PVD | 5677 (21.67) | 18,657 (27.93) | <0.001 |

| CKD | 7317 (27.93) | 22,289 (33.37) | <0.001 |

| Hospital Course | |||

| Length of stay (IQR days) | 4 (3–7) | 4 (2–6) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | Cardiogenic Shock | Ventricular Fibrillation | Atrial Fibrillation | Acute Renal Failure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| BMI | Normal | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Underweight | 1.81 (1.16–2.81) | 0.009 | 2.08 (1.24–3.50) | 0.006 | 2.38 (0.59–9.61) | 0.222 | 0.78 (0.63–0.96) | 0.021 | 0.90 (0.70–1.15) | 0.393 | |

| Overweight | 0.99 (0.64–1.54) | 0.967 | 0.97 (0.59–1.60) | 0.907 | 1.60 (0.44–5.88) | 0.476 | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 0.250 | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | 0.943 | |

| Class I Obesity | 0.56 (0.37–0.85) | 0.007 | 0.62 (0.39–0.99) | 0.043 | 0.39 (0.10–1.51) | 0.171 | 1.08 (0.92–1.27) | 0.357 | 0.92 (0.76–1.11) | 0.384 | |

| Class II Obesity | 0.38 (0.24–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.43 (0.27–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.10–1.41) | 0.146 | 1.16 (0.98–1.36) | 0.079 | 0.90 (0.75–1.08) | 0.265 | |

| Class III Obesity | 0.64 (0.43–0.95) | 0.026 | 0.24 (0.15–0.37) | <0.001 | 0.41 (0.12–1.40) | 0.154 | 1.39 (1.19–1.62) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.80–1.15) | 0.640 | |

| Age | 1.04 (1.03–1.05) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.95–0.96) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.05–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.198 | |

| Gender | Male | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Female | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | 0.021 | 0.64 (0.52–0.79) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.50–1.38) | 0.462 | 0.63 (0.60–0.67) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.83–0.95) | <0.001 | |

| Income | Low | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Low-Mid | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | 0.858 | 0.96 (0.74–1.24) | 0.733 | 0.63 (0.30–1.30) | 0.208 | 1.13 (1.06–1.21) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.82–0.95) | 0.001 | |

| High-Mid | 1.03 (0.81–1.32) | 0.805 | 1.21 (0.93–1.57) | 0.155 | 1.08 (0.56–2.09) | 0.822 | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.457 | |

| High | 1.00 (0.75–1.32) | 0.972 | 1.26 (0.94–1.69) | 0.117 | 1.75 (0.91–3.38) | 0.094 | 1.35 (1.25–1.47) | <0.001 | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 0.709 | |

| CAD | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 1.23 (1.02–1.49) | 0.031 | 1.69 (1.37–2.08) | <0.001 | 1.74 (1.03–2.98) | 0.040 | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | 0.909 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | 0.110 | |

| Hypertension | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 0.72 (0.58–0.90) | 0.003 | 0.50 (0.40–0.62) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.63–2.19) | 0.604 | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 0.002 | 0.96 (0.89–1.04) | 0.323 | |

| Smoking | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 0.046 | 0.76 (0.62–0.92) | 0.006 | 0.60 (0.35–1.02) | 0.060 | 0.92 (0.87–0.97) | 0.002 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.673 | |

| Dyslipidemia | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 0.72 (0.60–0.87) | 0.001 | 1.01 (0.82–1.24) | 0.949 | 1.23 (0.73–2.06) | 0.439 | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.414 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.311 | |

| PVD | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 1.07 (0.87–1.32) | 0.508 | 1.98 (1.61–2.43) | <0.001 | 2.21 (1.32–3.72) | 0.003 | 1.43 (1.34–1.52) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 0.007 | |

| CKD | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 1.67 (1.37–2.02) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.50–2.33) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.57–1.80) | 0.951 | 1.06 (0.99–1.12) | 0.073 | 4.88 (4.57–5.21) | <0.001 | |

| 1 Year Mortality | 1 Year Readmission for HF | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value * | aHR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value * | aHR (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| BMI | Normal | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Underweight | 1.41 (0.44–4.60) | 0.564 | 1.58 (0.49–5.15) | 0.447 | 0.92 (0.60–1.41) | 0.686 | 0.93 (0.61–1.43) | 0.754 | |

| Overweight | 0.64 (0.18–2.28) | 0.493 | 0.75 (0.21–2.68) | 0.663 | 0.89 (0.59–1.33) | 0.559 | 0.85 (0.57–1.28) | 0.440 | |

| Class I Obesity | 0.41 (0.14–1.19) | 0.101 | 0.59 (0.20–1.73) | 0.334 | 0.75 (0.53–1.06) | 0.104 | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 0.094 | |

| Class II Obesity | 0.48 (0.17–1.36) | 0.169 | 0.73 (0.26–2.07) | 0.553 | 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | 0.042 | 0.71 (0.50–0.99) | 0.049 | |

| Class III Obesity | 0.46 (0.17–1.25) | 0.130 | 0.80 (0.29–2.18) | 0.659 | 0.65 (0.47–0.91) | 0.013 | 0.68 (0.49–0.96) | 0.026 | |

| Age | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | <0.001 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.002 | |

| Gender | Male | Ref | - | - | - | Ref | - | - | - |

| Female | 0.91 (0.71–1.18) | 0.490 | - | - | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.416 | - | - | |

| Income | Low | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Low-Mid | 1.41 (1.03–1.95) | 0.034 | 1.36 (0.99–1.88) | 0.060 | 1.09 (1.00–1.19) | 0.058 | 1.08 (0.99–1.19) | 0.077 | |

| High-Mid | 1.25 (0.87–1.80) | 0.218 | 1.17 (0.82–1.69) | 0.384 | 1.16 (1.05–1.27) | 0.003 | 1.15 (1.04–1.26) | 0.005 | |

| High | 1.48 (1.00–2.19) | 0.049 | 1.36 (0.92–2.02) | 0.124 | 1.06 (0.95–1.19) | 0.287 | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.527 | |

| CAD | No | Ref | - | - | - | Ref | - | - | - |

| Yes | 1.07 (0.82–1.38) | 0.626 | - | - | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | 0.793 | - | - | |

| Hypertension | No | Ref | - | - | - | Ref | - | Ref | - |

| Yes | 0.92 (0.66–1.28) | 0.609 | - | - | 1.36 (1.22–1.51) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.21–1.50) | <0.001 | |

| Smoking | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | - | - |

| Yes | 0.79 (0.60–1.03) | 0.083 | 0.89 (0.68–1.17) | 0.401 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | 0.961 | - | - | |

| Dyslipidemia | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | - | - |

| Yes | 0.56 (0.43–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.51 (0.39–0.67) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.844 | - | - | |

| PVD | No | Ref | - | Ref | Ref | - | Ref | - | |

| Yes | 1.26 (0.93–1.71) | 0.143 | 1.16 (0.85–1.59) | 0.350 | 1.11 (1.02–1.21) | 0.021 | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 0.205 | |

| CKD | No | Ref | - | Ref | - | Ref | - | - | - |

| Yes | 1.82 (1.41–2.35) | <0.001 | 1.67 (1.29–2.17) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | 0.444 | - | - | |

References

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: A comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 118, 3272–3287, Erratum in Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 1453. [Google Scholar]

- Shahim, B.; Kapelios, C.J.; Savarese, G.; Lund, L.H. Global Public Hea lth Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Card. Fail. Rev. 2023, 9, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Khan, M.S.; Patel, K.V.; Bhatt, D.L.; Verma, S. Predicting and preventing heart failure in type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023, 11, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Manzanares, R.; Anguita-Gámez, M.; Muñiz, J.; Barrios, V.; Gimeno-Orna, J.A.; Pérez, A.; Rodríguez-Padial, L.; Anguita, M.; Investigators, D.-I.s. Prevalence and incidence of heart failure in type 2 diabetes patients: Results from a nationwide prospective cohort—The DIABET-IC study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyagaturu, H.S.; Bolton, A.R.; Li, S.; Kumar, A.; Shah, K.R.; Katz, D. Effect of diabetes mellitus on 30 and 90-day readmissions of patients with heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 155, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Pinto, A.; Giusti, A.M.; Lenzi, A.; Poggiogalle, E. Obesity or BMI Paradox? Beneath the Tip of the Iceberg. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Boyko, E.J. The Evidence for an Obesity Paradox in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 2018, 42, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, H.; Bodair, R.; Mahfoud, Z.; Dargham, S.; Al Suwaidi, J.; Jneid, H.; Abi Khalil, C. Overweight and obesity are associated with better survival in STEMI patients with diabetes. Obesity 2023, 31, 2834–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Rhee, C.M.; Chou, J.; Ahmadi, S.F.; Park, J.; Chen, J.L.; Amin, A.N. The Obesity Paradox in Kidney Disease: How to Reconcile it with Obesity Management. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haass, M.; Kitzman, D.W.; Anand, I.S.; Miller, A.; Zile, M.R.; Massie, B.M.; Carson, P.E. Body mass index and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: Results from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (I-PRESERVE) trial. Circ. Heart Fail. 2011, 4, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, E.K.; Ozkan, B.; Ndumele, C.E. Heart failure and obesity: The latest pandemic. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 78, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarese, G.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Lindberg, F.; Anker, M.S.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Bäck, M.; Braunschweig, F.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Butler, J.; Cannata, A. Heart failure and obesity: Translational approaches and therapeutic perspectives. A scientific statement of the Heart Failure Association of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elagizi, A.; Carbone, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Mehra, M.R.; Ventura, H.O. Implications of obesity across the heart failure continuum. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, S.; Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R. Obesity and heart failure: Focus on the obesity paradox. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwich, T.B.; Broderick, S.; Chen, L.; McCullough, P.A.; Strzelczyk, T.; Kitzman, D.W.; Fletcher, G.; Safford, R.E.; Ewald, G.; Fine, L.J. Relation among body mass index, exercise training, and outcomes in chronic systolic heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 1754–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøgh-Sørensen, S.; Campbell, R.T.; Claggett, B.L.; Lewis, E.F.; Docherty, K.F.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Lindner, M.; Biering-Sørensen, T.; Solomon, S.D.; Platz, E. The intersection of obesity and acute heart failure: Cardiac structure and function and congestion across BMI categories. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2025, 14, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, Y.; He, W.; Liu, X.; Zhu, W. Association of body mass index and prognosis in patients with HFpEF: A dose-response meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 361, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oga, E.A.; Eseyin, O.R. The Obesity Paradox and Heart Failure: A Systematic Review of a Decade of Evidence. J. Obes. 2016, 2016, 9040248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.R.; Ordóñez-Mena, J.M.; Roalfe, A.K.; Taylor, K.S.; Goyder, C.R.; Hobbs, F.R.; Taylor, C.J. Body mass index and survival in people with heart failure. Heart 2023, 109, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumayyaleh, M.; Demmer, J.; Krack, C.; Pilsinger, C.; El-Battrawy, I.; Aweimer, A.; Lang, S.; Mügge, A.; Akin, I. Incidence of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias in obese patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction treated with sacubitril/valsartan. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 2999–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, W.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, J.H.; Choi, K.H.; Park, T.K.; Lee, J.M.; Song, Y.B.; Hahn, J.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Ahn, C.M.; et al. Impact of the Obesity Paradox Between Sexes on In-Hospital Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, V.; Lambiase, P. Obesity and atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and novel therapeutic opportunities. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 2019, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuiman, M.; Briffa, T.; Divitini, M.; Chew, D.; Eikelboom, J.; McQuillan, B.; Hung, J. A cohort study examination of established and emerging risk factors for atrial fibrillation: The Busselton Health Study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 29, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, P.; Cleland, J.G.; Pellicori, P.; Clark, A.L.; Hepburn, D.; Kilpatrick, E.S.; Perrone-Filardi, P.; Zhang, J.; Atkin, S.L. The obesity paradox in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Relationship of body mass index to prognosis: A cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afghahi, H.; Nasic, S.; Svensson, J.; Rydell, H.; Wärme, A.; Peters, B. The association between body mass index and mortality in diabetic patients with end-stage renal disease is different in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2510549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Ha, K.H.; Kim, D.J. Body mass index and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome by diabetes status: The obesity paradox in a Korean national cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.A.; Heizer, G.; O’Connor, C.M.; Schulte, P.J.; Dickstein, K.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Armstrong, P.W.; Hasselblad, V.; Mills, R.M.; McMurray, J.J.V.; et al. Hypotension During Hospitalization for Acute Heart Failure Is Independently Associated With 30-Day Mortality. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphael, C.E.; Whinnett, Z.I.; Davies, J.E.; Fontana, M.; Ferenczi, E.A.; Manisty, C.H.; Mayet, J.; Francis, D.P. Quantifying the paradoxical effect of higher systolic blood pressure on mortality in chronic heart failure. Heart 2009, 95, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjola, V.P.; Mullens, W.; Banaszewski, M.; Bauersachs, J.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Chioncel, O.; Collins, S.P.; Doehner, W.; Filippatos, G.S.; Flammer, A.J.; et al. Organ dysfunction, injury and failure in acute heart failure: From pathophysiology to diagnosis and management. A review on behalf of the Acute Heart Failure Committee of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, A.L.; Meyer, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Lam, C.S.P.; Kaye, D.M. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology. Circulation 2018, 138, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.S.P.; Gamble, G.D.; Ling, L.H.; Sim, D.; Leong, K.T.G.; Yeo, P.S.D.; Ong, H.Y.; Jaufeerally, F.; Ng, T.P.; Cameron, V.A.; et al. Mortality associated with heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction in a prospective international multi-ethnic cohort study. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 1770–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, E.; Wang, Y. Protective Effects of Estrogen on Cardiovascular Disease Mediated by Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5523516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E. Gender differences in fat metabolism. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2001, 4, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Ferranti, S.; Mozaffarian, D. The perfect storm: Obesity, adipocyte dysfunction, and metabolic consequences. Clin. Chem. 2008, 54, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumayyaleh, M.; Koepsel, K.; Erath, J.W.; Kuntz, T.; Klein, N.; Kovacs, B.; Duru, F.; Saguner, A.M.; Blockhaus, C.; Shin, D.I. Association of BMI with adherence and outcome in heart failure patients treated with wearable cardioverter defibrillator. ESC Heart Fail. 2025, 12, 1295–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, J.; Lloji, A.; Khan, M.S.; Hooda, U.; Malik, A.; Sharma, D.; Shah, A.; Aronow, W.S.; Michos, E.D.; Naidu, S.S. Impact of Body Mass Index on Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 175, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, A.; Saad, M.; Batool, R.M.; Ibrahim, Z.S.; Waqas, S.A.; Ahmed, S.Z.; Ahsan, S.I.; Aisha, E.; Aamer, H.; Sohail, M.U.; et al. Obesity paradox in coronary artery disease: National inpatient sample analysis. Coron. Artery Dis. 2025, 36, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wleklik, M.; Uchmanowicz, I.; Jankowska-PolaÅ„ska, B.; Andreae, C.; Regulska-Ilow, B. The Role of Nutritional Status in Elderly Patients with Heart Failure. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Tousoulis, D. The molecular mechanisms of obesity paradox. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Li, X. Evaluating the obesity paradox in patients with sepsis and cancer. Int. J. Obes. 2025, 49, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wleklik, M.; Lee, C.S.; Lewandowski, Ł.; Czapla, M.; Jędrzejczyk, M.; Aldossary, H.; Uchmanowicz, I. Frailty determinants in heart failure: Inflammatory markers, cognitive impairment and psychosocial interaction. ESC Heart Fail. 2025, 12, 2010–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, N.; Aranyó, J.; Enjuanes, C.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Ruiz, S.; Gonzalez-Robledo, G.; Meroño, O.; De Ramon, M.; Moliner, P.; Bruguera, J. Differences in neurohormonal activity partially explain the obesity paradox in patients with heart failure: The role of sympathetic activation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 181, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.Y.; Chen, H.H.; Hsu, H.Y.; Tsai, M.C.; Hsu, L.Y.; Hwang, L.C.; Chien, K.L.; Lin, C.J.; Yeh, T.L. Obesity phenotypes and their relationships with atrial fibrillation. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, M.J.; German, C.A.; Carnethon, M.; Soliman, E.Z.; Bertoni, A.G.; Yeboah, J. Race, Body Mass Index, and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e018592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrasik, G.; Goldenberg, I.; McNITT, S.; Moss, A.J.; Zareba, W. Obesity as a risk factor for sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias in MADIT II patients. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2007, 18, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, B.; Nair, A.P.; Misra, A.; Scott, C.Z.; Mahar, J.H.; Fedson, S. Neprilysin Inhibitors in Heart Failure: The Science, Mechanism of Action, Clinical Studies, and Unanswered Questions. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2023, 8, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajjar, A.; Raju, A.K.; Gajjar, A.; Menon, M.; Shah, S.A.Y.; Dani, S.; Weinberg, A. SGLT2 Inhibitors and GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Cardiovascular–Kidney–Metabolic Syndrome. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oreopoulos, A.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; McAlister, F.A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Fonarow, G.C.; Norris, C.M.; Johnson, J.A.; Padwal, R.S. Association between direct measures of body composition and prognostic factors in chronic heart failure. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liang, W.; Dong, B.; Xue, R.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, W.; Huang, P. Association of Body-Weight Fluctuation With Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 689591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, M.R.; Mourilhe-Rocha, R.; Chang, H.-Y.; Volterrani, M.; Ban, H.N.; de Albuquerque, D.C.; Chung, E.; Fonseca, C.; Lopatin, Y.; Serrano, J.A.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on heart failure management: Global experience of the OPTIMIZE Heart Failure Care network. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 363, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, S.J.; Velicki, L.; Okwose, N.C.; Harwood, A.; McGregor, G.; Ristic, A.; Banerjee, P.; Seferovic, P.M.; MacGowan, G.A.; Jakovljevic, D.G. Insights into heart failure hospitalizations, management, and services during and beyond COVID-19. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodeski, E.Z.; Goyal, P.; Cox, Z.L.; Thibodeau, J.T.; Reay, R.E.; Rasmusson, K.; Rogers, J.G.; Starling, R.C. Virtual visits for care of patients with heart failure in the era of COVID-19: A statement from the Heart Failure Society of America. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromage, D.I.; Cannatà, A.; Rind, I.A.; Gregorio, C.; Piper, S.; Shah, A.M.; McDonagh, T.A. The impact of COVID-19 on heart failure hospitalization and management: Report from a Heart Failure Unit in London during the peak of the pandemic. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.E.; Vaduganathan, M.; Khan, M.S.; Papadimitriou, L.; Long, R.C.; Hernandez, G.A.; Moore, C.K.; Lennep, B.W.; Mcmullan, M.R.; Butler, J. Reductions in heart failure hospitalizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 26, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isath, A.; Malik, A.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Goel, A.; Hajra, A.; Dhand, A.; Lanier, G.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Lavie, C.J.; Gass, A.L. COVID-19, heart failure hospitalizations, and outcomes: A nationwide analysis. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2023, 48, 101541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severino, P.; D’Amato, A.; Saglietto, A.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Marini, C.; Schiavone, M.; Ghionzoli, N.; Pirrotta, F.; Troiano, F.; Cannillo, M. Reduction in heart failure hospitalization rate during coronavirus disease 19 pandemic outbreak. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 4182–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babapoor-Farrokhran, S.; Alzubi, J.; Port, Z.; Sooknanan, N.; Ammari, Z.; Al-Sarie, M.; Bozorgnia, B. Impact of COVID-19 on heart failure hospitalizations. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021, 3, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertagnin, E.; Greco, A.; Bottaro, G.; Zappulla, P.; Romanazzi, I.; Russo, M.D.; Presti, M.L.; Valenti, N.; Sollano, G.; Calvi, V. Remote monitoring for heart failure management during COVID-19 pandemic. IJC Heart Vasc. 2021, 32, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzuoli, A.; Metra, M.; Collins, S.P.; Adamo, M.; Ambrosy, A.P.; Antohi, L.E.; Ben Gal, T.; Farmakis, D.; Gustafsson, F.; Hill, L. Heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical, diagnostic, management, and organizational dilemmas. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 3713–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanbour, S.; Ageeb, R.A.; Malik, R.A.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Impact of bodyweight loss on type 2 diabetes remission: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.W.; Jakicic, J.M.; Blackburn, G.; Bloomquist, P.; Bray, G.A.; Clark, J.M.; Coday, M.; Curtis, J.M.; Egan, C.; Evans, M.; et al. Association of the magnitude of weight loss and changes in physical fitness with long-term cardiovascular disease outcomes in overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes: A post-hoc analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora, E.; Díez-López, C.; Lupón, J.; de Antonio, M.; Domingo, M.; Santesmases, J.; Troya, M.I.; Díez-Quevedo, C.; Altimir, S.; Bayes-Genis, A. Weight Loss in Obese Patients With Heart Failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J.; Shah, S.J.; Petrie, M.C.; Borlaug, B.A.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Davies, M.J.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kitzman, D.W.; Møller, D.V.; Verma, S.; et al. Semaglutide versus placebo in people with obesity-related heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A pooled analysis of the STEP-HFpEF and STEP-HFpEF DM randomised trials. Lancet 2024, 403, 1635–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhund, P.S.; Kondo, T.; Butt, J.H.; Docherty, K.F.; Claggett, B.L.; Desai, A.S.; Vaduganathan, M.; Gasparyan, S.B.; Bengtsson, O.; Lindholm, D.; et al. Dapagliflozin across the range of ejection fraction in patients with heart failure: A patient-level, pooled meta-analysis of DAPA-HF and DELIVER. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Underweight N (%) | Normal Weight N (%) | Overweight N (%) | Class I Obesity N (%) | Class II Obesity N (%) | Class III Obesity N (%) | p-Value 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 736 (2.81%) | 774 (2.95%) | 1412 (5.39%) | 4038 (15.41%) | 4928 (18.81%) | 14,311 (54.62%) | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 77.92 (11.21) | 76.01 (12.13) | 73.42 (11.90) | 69.95 (12.30) | 67.27 (12.37) | 63.65 (12.77) | <0.001 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 330 (44.84) | 437 (56.46) | 776 (54.96) | 2184 (54.09) | 2637 (53.51) | 6099 (42.62) | <0.001 |

| Income 2 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 239 (32.47) | 245 (31.65) | 445 (31.52) | 1356 (33.58) | 1642 (33.32) | 5201 (36.34) | <0.001 |

| Low-middle | 181 (24.59) | 194 (25.06) | 395 (27.97) | 1123 (27.81) | 1362 (27.64) | 4156 (29.04) | |

| Middle-High | 179 (24.32) | 179 (23.13) | 327 (23.16) | 927 (22.96) | 1157 (23.48) | 3150 (22.01) | |

| High | 137 (18.61) | 156 (20.16) | 245 (17.35) | 632 (15.65) | 767 (15.56) | 1804 (12.61) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| CAD | 378 (51.36) | 425 (54.91) | 824 (58.36) | 2172 (53.79) | 2391 (48.52) | 5162 (36.07) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 470 (63.86) | 511 (66.02) | 1093 (77.41) | 3100 (76.77) | 3839 (77.90) | 10,678 (74.61) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 293 (39.81) | 303 (39.15) | 608 (43.06) | 1896 (46.95) | 2219 (45.03) | 5638 (39.40) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 308 (41.85) | 374 (48.32) | 777 (55.03) | 2239 (55.45) | 2607 (52.90) | 6563 (45.86) | <0.001 |

| PVD | 267 (36.28) | 253 (32.69) | 463 (32.79) | 1081 (26.77) | 1191 (24.17) | 2422 (16.92) | <0.001 |

| CKD | 199 (27.04) | 256 (33.07) | 491 (34.77) | 1253 (31.03) | 1500 (30.44) | 3618 (25.28) | <0.001 |

| Hospital Course | |||||||

| Length of stay (IQR days) | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–9) | 4 (3–7) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–7) | <0.001 |

| Mortality | Cardiogenic Shock | Ventricular Fibrillation | Atrial Fibrillation | Acute Renal Failure | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OR | aOR | n | OR | aOR | n | OR | aOR | n | OR | aOR | n | OR | aOR | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | ||||||

| Underweight | 57 | 1.83 | 1.81 | 40 | 1.72 | 2.08 | 6 | 2.11 | 2.38 | 322 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 167 | 0.81 | 0.90 |

| (1.18–2.83) | (1.16–2.81) | (1.03–2.87) | (1.24–3.50) | (0.53–8.48) | (0.59–9.61) | (0.68–1.02) | (0.63–0.96) | (0.64–1.03) | (0.70–1.15) | ||||||

| Normal weight † | 34 | Ref | Ref | 25 | Ref | Ref | 3 | Ref | Ref | 374 | Ref | Ref | 205 | Ref | Ref |

| Overweight | 53 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 47 | 1.03 | 0.97 | 10 | 1.83 | 1.60 | 597 | 0.78 | 0.90 | 376 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| (0.55–1.32) | (0.64–1.54) | (0.63–1.69) | (0.59–1.60) | (0.50–6.68) | (0.44–5.88) | (0.66–0.93) | (0.75–1.08) | (0.83–1.23) | (0.80–1.23) | ||||||

| Class I Obesity | 74 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 90 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 7 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 1689 | 0.77 | 1.08 | 971 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| (0.27–0.61) | (0.37–0.85) | (0.44–1.07) | (0.39–0.99) | (0.12–1.73) | (0.10–1.51) | (0.66–0.90) | (0.92–1.27) | (0.74–1.05) | (0.76–1.11) | ||||||

| Class II Obesity | 54 | 0.24 | 0.38 | 83 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 9 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 1977 | 0.82 | 1.16 | 1153 | 0.85 | 0.90 |

| (0.16–3.73) | (0.24–0.59) | (0.33–0.81) | (0.27–0.68) | (0.13–1.74) | (0.10–1.41) | (0.62–0.83) | (0.98–1.36) | (0.71–1.01) | (0.75–1.08) | ||||||

| Class III Obesity | 215 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 141 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 29 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 5361 | 0.64 | 1.39 | 3213 | 0.80 | 0.96 |

| (0.23–0.48) | (0.43–0.95) | (0.19–0.46) | (0.15–0.37) | (0.16–1.72) | (0.12–1.40) | (0.55–0.74) | (1.19–1.62) | (0.68–0.95) | (0.80–1.15) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-Khoury, R.; Mahfoud, Z.; Dargham, S.; Pal, M.A.; Jayyousi, A.; Al Suwaidi, J.; Abi Khalil, C. Obesity Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Mortality and Readmission in Heart Failure Patients with Diabetes. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123086

El-Khoury R, Mahfoud Z, Dargham S, Pal MA, Jayyousi A, Al Suwaidi J, Abi Khalil C. Obesity Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Mortality and Readmission in Heart Failure Patients with Diabetes. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123086

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-Khoury, Rayane, Ziyad Mahfoud, Soha Dargham, Mujtaba Ashal Pal, Amin Jayyousi, Jassim Al Suwaidi, and Charbel Abi Khalil. 2025. "Obesity Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Mortality and Readmission in Heart Failure Patients with Diabetes" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123086

APA StyleEl-Khoury, R., Mahfoud, Z., Dargham, S., Pal, M. A., Jayyousi, A., Al Suwaidi, J., & Abi Khalil, C. (2025). Obesity Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Mortality and Readmission in Heart Failure Patients with Diabetes. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3086. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123086