Expression of Connexins 37/40 and Pannexin 1 in Early Human and Yotari (Dab1−/−) Meninges Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Tissue Collection and Preparation

2.2. Animal Model

2.3. Immunohistochemistry and Microscopy

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Semi-Quantitative Assessment of Staining Intensity

3. Results

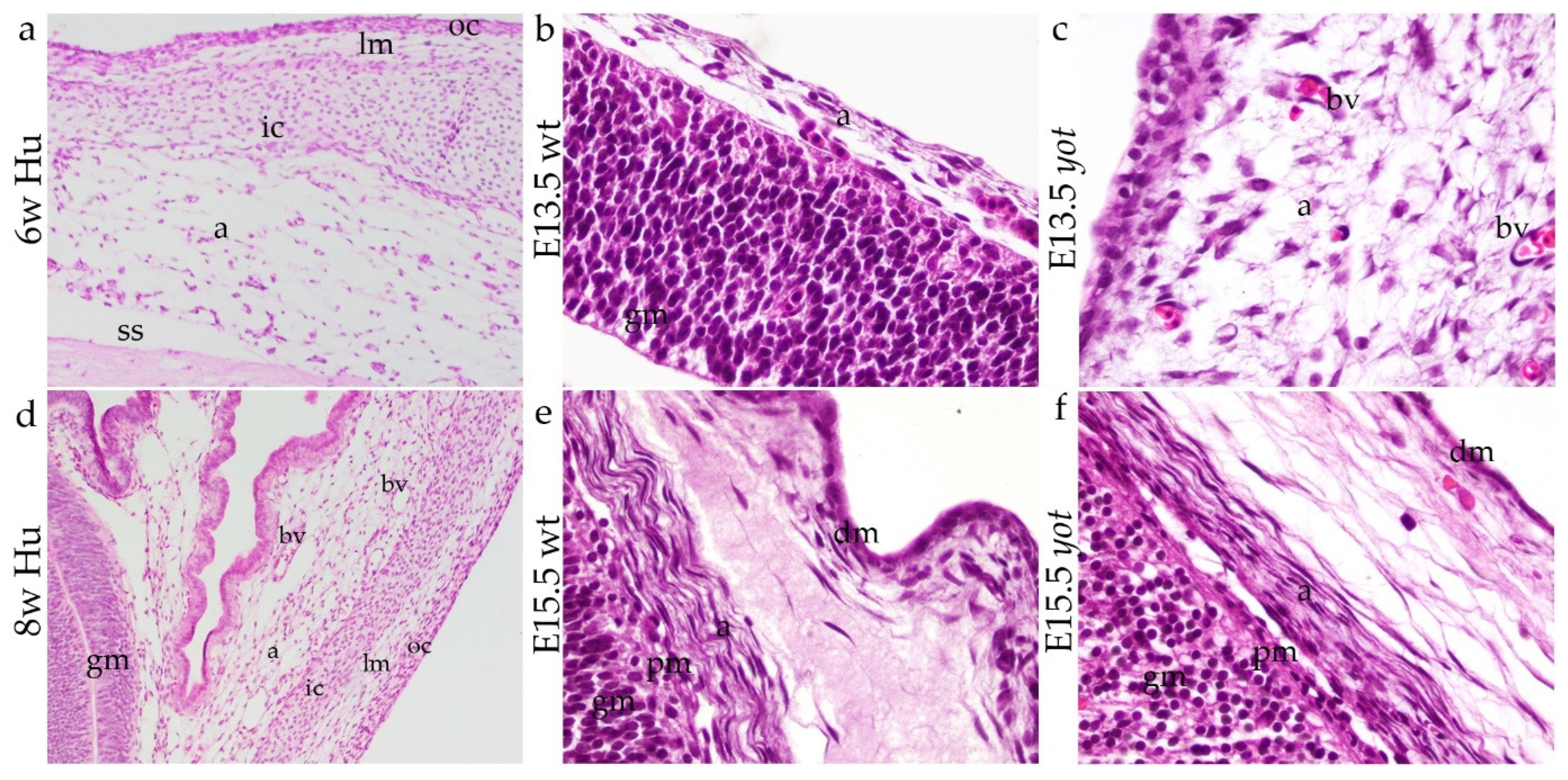

3.1. Development of Meninges

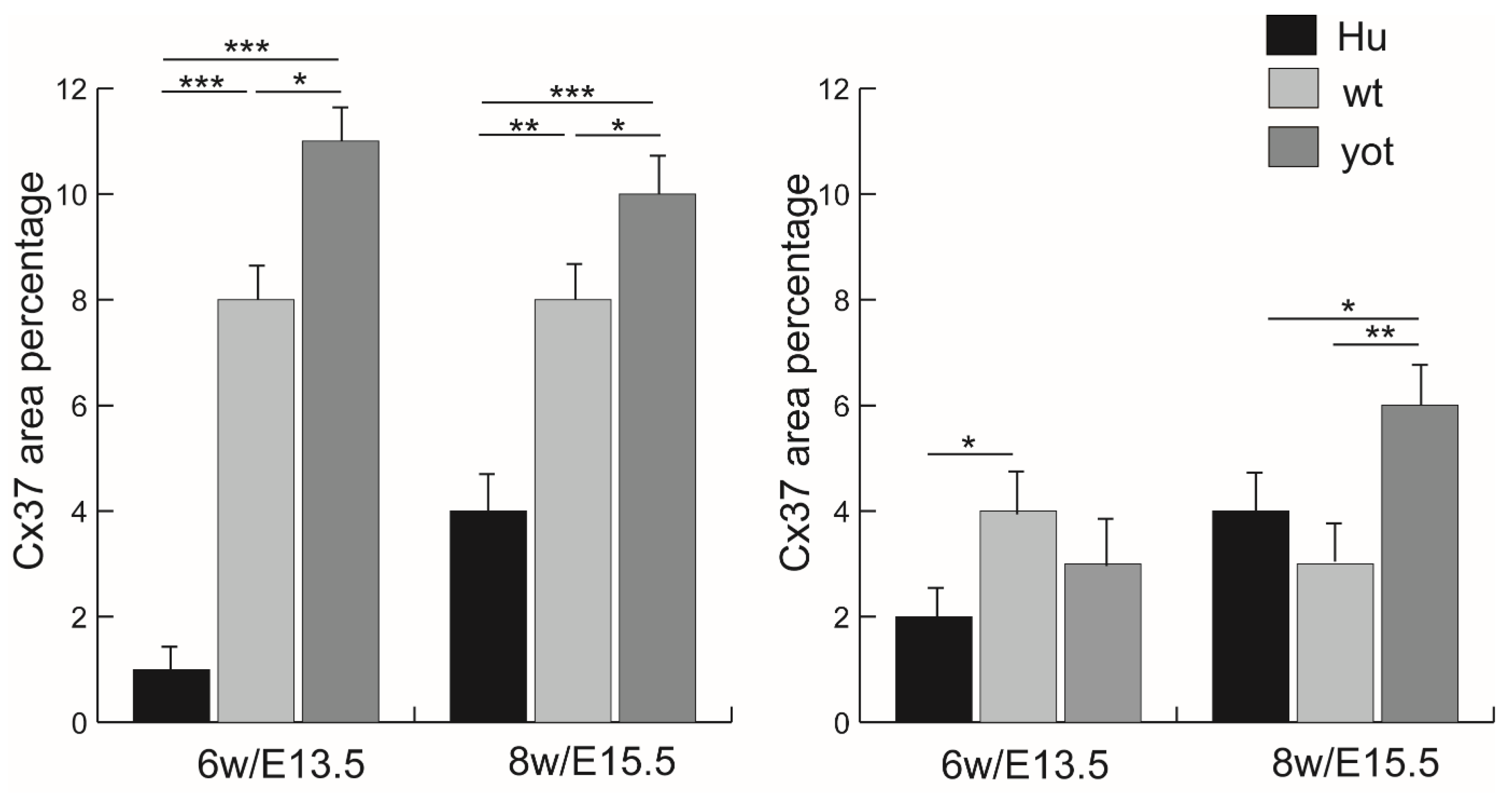

3.2. Immunofluorescence Staining with Cx37 Marker

3.3. Immunofluorescence Staining with Cx40 Marker

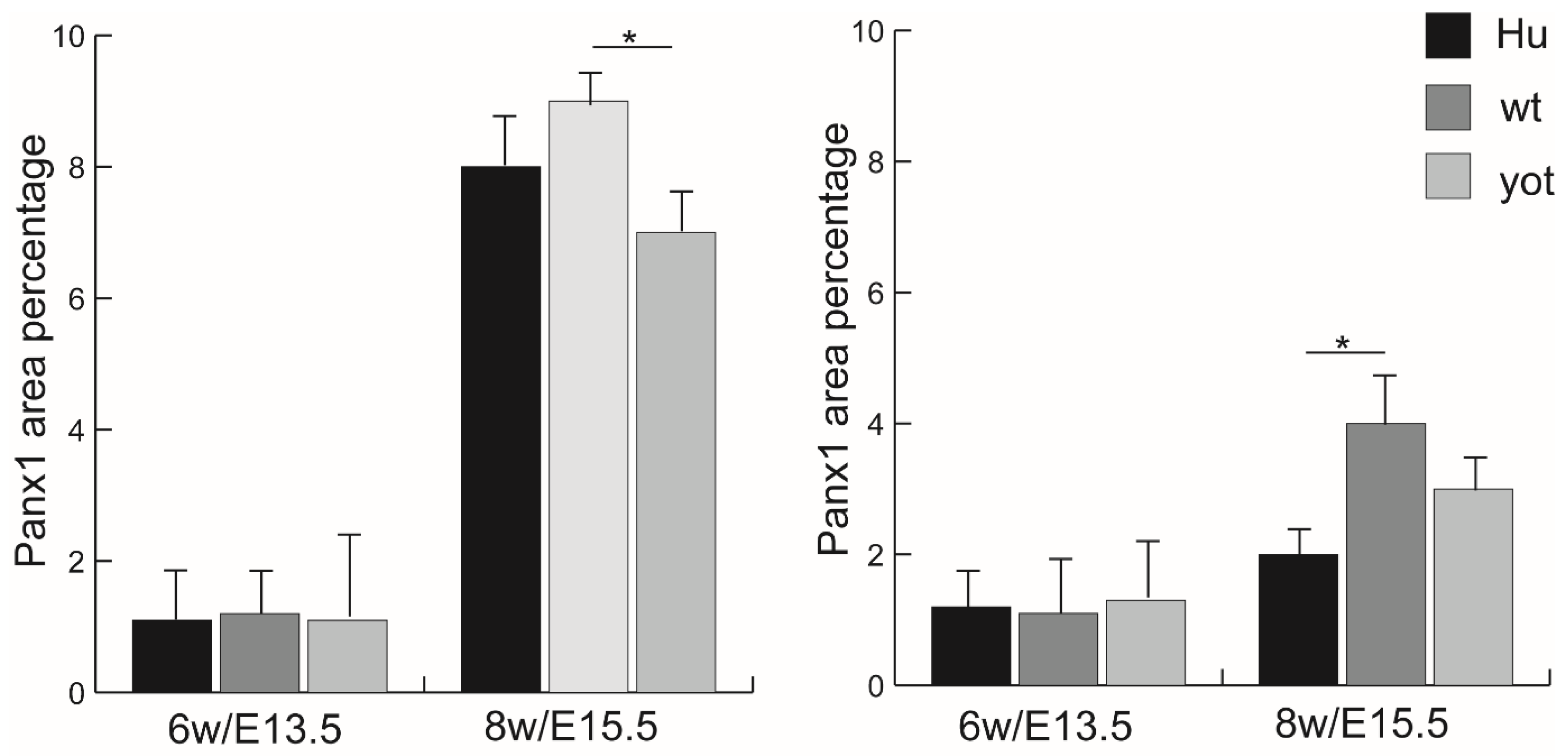

3.4. Immunofluorescence Staining with Panx1 Marker

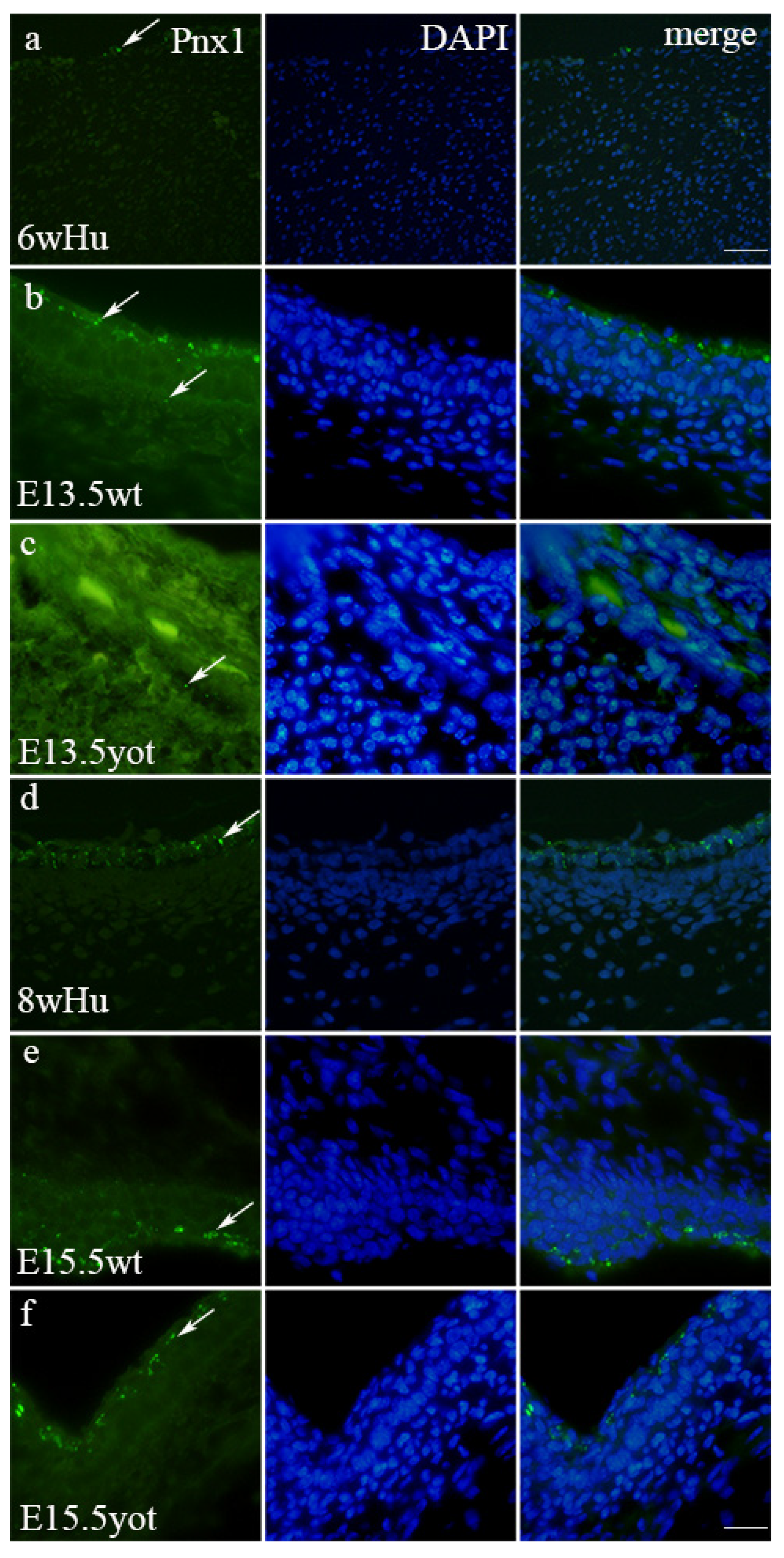

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| a | Arachnoid |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| bv | Blood vessel |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRL | Crown-rump length |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| Cx37 | Connexin 37 |

| Cx40 | Connexin 40 |

| Dab1 | Disabled-1 |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| dm | Dura mater |

| E | Embryonic day |

| GJ | Gap junctions |

| gm | Gray matter |

| HE | Hematoxylin eosin |

| HC | Hemichannels |

| HU | Human |

| ic | Inner mesenchymal condensation |

| lm | Loose mesenchyme |

| oc | Outer mesenchymal condensation |

| Panx1 | Pannexin1 |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| pm | Pia mater |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ss | Subarachnoid space |

| yot | Yotari |

| wt | Wild-type |

References

- Dasgupta, K.; Jeong, J. Developmental biology of the meninges. Genesis 2019, 57, e23288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, J.; Liu, C. A novel perspective of calvarial development: The cranial morphogenesis and differentiation regulated by dura mater. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1420891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decimo, I.; Fumagalli, G.; Berton, V.; Krampera, M.; Bifari, F. Meninges: From protective membrane to stem cell niche. Am. J. Stem Cells 2012, 1, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Derk, J.; Jones, H.E.; Como, C.; Pawlikowski, B.; Siegenthaler, J.A. Living on the Edge of the CNS: Meninges Cell Diversity in Health and Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 703944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; Chen, X. Reimagining the meninges from a neuroimmune perspective: A boundary, but not peripheral. J. Neuroinf 2024, 21, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talukdar, S.; Emdad, L.; Das, S.K.; Fisher, P.B. GAP junctions: Multifaceted regulators of neuronal differentiation. Tissue Barriers 2022, 10, 1982349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Acosta, F.M.; Jiang, J.X. Gap Junctions or Hemichannel-Dependent and Independent Roles of Connexins in Fibrosis, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions, and Wound Healing. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swayne, L.A.; Bennett, S.A. Connexins and pannexins in neuronal development and adult neurogenesis. BMC Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, M.; Decrock, E.; Wang, N.; Bol, M.; Vinken, M.; Bultynck, G.; Leybaert, L. The dual face of connexin-based astroglial Ca2+ communication: A key player in brain physiology and a prime target in pathology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2211–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.E.; Nagy, J.I. Connexin36 expression in major centers of the auditory system in the CNS of mouse and rat: Evidence for neurons forming purely electrical synapses and morphologically mixed synapses. Neuroscience 2015, 303, 604–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash, J.E.; Olson, C.O.; Davidson, K.G.; Yasumura, T.; Kamasawa, N.; Nagy, J.I. Identification of connexin36 in gap junctions between neurons in rodent locus coeruleus. Neuroscience 2007, 147, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jossin, Y. Reelin Functions, Mechanisms of Action and Signaling Pathways During Brain Development and Maturation. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneshima, H.; Nagata, E.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamada, M.; Nakajima, K.; Miyata, T.; Ogawa, M.; Mikoshiba, K. A novel neurological mutant mouse, yotari, which exhibits reeler-like phenotype but expresses CR-50 antigen/reelin. Neurosci. Res. 1997, 29, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Cooper, J.A. Optogenetic control of the Dab1 signaling pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segarra, M.; Aburto, M.R.; Cop, F.; Llao-Cid, C.; Hartl, R.; Damm, M.; Bethani, I.; Parrilla, M.; Husainie, D.; Schanzer, A.; et al. Endothelial Dab1 signaling orchestrates neuro-glia-vessel communication in the central nervous system. Science 2018, 361, eaao2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rahilly, R.; Gardner, E. The timing and sequence of events in the development of the human nervous system during the embryonic period proper. Z. Anat. Entwicklungsgeschichte 1971, 134, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rahilly, R. Early human development and the chief sources of information on staged human embryos. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1979, 9, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiler, K. The House Mouse: Atlas of Mouse Development; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Racetin, A.; Filipovic, N.; Lozic, M.; Ogata, M.; Gudelj Ensor, L.; Kelam, N.; Kovacevic, P.; Watanabe, K.; Katsuyama, Y.; Saraga-Babic, M.; et al. A Homozygous Dab1(−/−) Is a Potential Novel Cause of Autosomal Recessive Congenital Anomalies of the Mice Kidney and Urinary Tract. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastar, V.; Lozic, M.; Kelam, N.; Filipovic, N.; Bernard, B.; Katsuyama, Y.; Vukojevic, K. Connexin Expression Is Altered in Liver Development of Yotari (dab1 −/−) Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazic Maras, E.; Kelam, N.; Racetin, A.; Haque, E.; Drazic, M.; Vukojevic, K.; Katsuyama, Y.; Saraga-Babic, M.; Filipovic, N. Autophagy markers expression pattern in developing liver of the yotari (dab1(−/−)) mice and humans. Acta Histochem. 2025, 127, 152224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, P.; Maglica, M.; Kelam, N.; Filipovic, N.; Rizikalo, A.; Perutina, I.; Miskovic, J.; Katsuyama, Y.; Vukojevic, K. Loss of Dab1 Alters Expression Patterns of Endocytic and Signaling Molecules During Embryonic Lung Development in Mice. Life 2025, 15, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorovic, P.; Kelam, N.; Racetin, A.; Filipovic, N.; Katsuyama, Y.; Saraga-Babic, M.; Vukojevic, K. Expression Pattern of Dab1, Reelin, PGP9.5 and Sox2 in the Stomach of Yotari (Dab1(−/−)) Mice. Genes 2025, 16, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juric, M.; Zeitler, J.; Vukojevic, K.; Bocina, I.; Grobe, M.; Kretzschmar, G.; Saraga-Babic, M.; Filipovic, N. Expression of Connexins 37, 43 and 45 in Developing Human Spinal Cord and Ganglia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesko, J.; Rastovic, P.; Miskovic, J.; Soljic, V.; Pastar, V.; Zovko, Z.; Filipovic, N.; Katsuyama, Y.; Saraga-Babic, M.; Vukojevic, K. The Interplay of Cx26, Cx32, Cx37, Cx40, Cx43, Cx45, and Panx1 in Inner-Ear Development of Yotari (dab1−/−) Mice and Humans. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.S.; Angelov, S.N.; Simon, A.M.; Burt, J.M. Cx40 is required for, and cx37 limits, postischemic hindlimb perfusion, survival and recovery. J. Vasc. Res. 2012, 49, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, B.S.; Sparks, M.A.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Lopez Domowicz, D.A.; Zhu, H.; McMahon, T.J. Pannexin 1 channels control the hemodynamic response to hypoxia by regulating O(2)-sensitive extracellular ATP in blood. Am. J. Physiology Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H1055–H1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age (Weeks) | CRL (mm) | Carnegie Stage | No. | No. Karyotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 14 | 16 | 4 | 2 46, XX; 2 46, XY |

| 8 | 27 | 22 | 4 | 2 46, XX; 2 46, XY |

| Primary Antibodies’ Immunoreactivity in the Meninges at Two Developmental Periods | Cx37 | Cx40 | Pnx1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leptomeninges | Pachymeninges | Leptomeninges | Pachymeninges | Leptomeninges | Pachymeninges | ||

| 6w/E13.5 | Hu | −/+ | ++ | −/+ | + | + | + |

| wt | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | |

| yot | +++ | ++ | + | + | + | + | |

| 8w/E15.5 | Hu | +++ | +++ | ++ | + | +++ | + |

| wt | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | |

| yot | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | +++ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puljiz, M.; Filipović, N.; Kelam, N.; Racetin, A.; Katsuyama, Y.; Vukojević, K. Expression of Connexins 37/40 and Pannexin 1 in Early Human and Yotari (Dab1−/−) Meninges Development. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123088

Puljiz M, Filipović N, Kelam N, Racetin A, Katsuyama Y, Vukojević K. Expression of Connexins 37/40 and Pannexin 1 in Early Human and Yotari (Dab1−/−) Meninges Development. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123088

Chicago/Turabian StylePuljiz, Marko, Natalija Filipović, Nela Kelam, Anita Racetin, Yu Katsuyama, and Katarina Vukojević. 2025. "Expression of Connexins 37/40 and Pannexin 1 in Early Human and Yotari (Dab1−/−) Meninges Development" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123088

APA StylePuljiz, M., Filipović, N., Kelam, N., Racetin, A., Katsuyama, Y., & Vukojević, K. (2025). Expression of Connexins 37/40 and Pannexin 1 in Early Human and Yotari (Dab1−/−) Meninges Development. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3088. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123088