Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolic Disorders in the Occurrence and Development of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Implications for Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Association Between Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and AAD

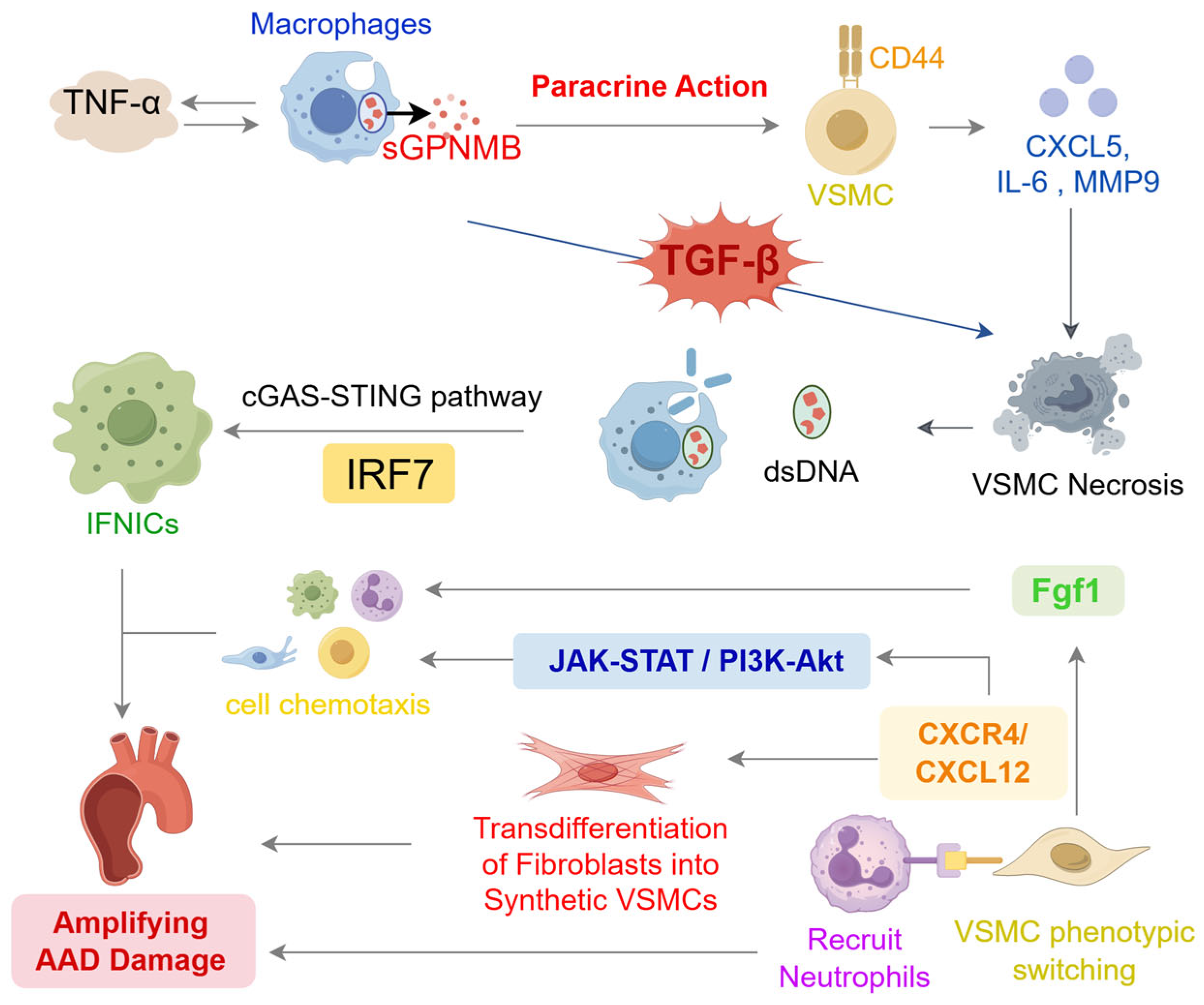

2.1. Physiological Functions of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in the Aorta

2.2. Pathological Changes of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in AAD

2.2.1. Phenotypic Switching of VSMC in AAD

2.2.2. Programmed Cell Death in VSMC Associated with AAD Progression

2.2.3. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling Mediated by VSMCs in AAD

3. Regulation of Epigenetic Modifications on the Core Functions of VSMCs

3.1. TET2-Mediated DNA Demethylation Maintains the Contractile Program of VSMCs

3.2. Histone Modification Programs Governing VSMC Identity

3.3. MicroRNA-Mediated Epigenetic Regulation in AAD

3.4. Outstanding Knowledge Gaps in Epigenetic Control of VSMCs in AAD

4. VSMCs Heterogeneity and Cell–Cell Communication Revealed

5. Metabolic Abnormalities of VSMC in AAD

5.1. Metabolic Reprogramming of Glucose Pathways in VSMCs and Its Role in AAD

5.2. Abnormal Amino Acid Metabolism in VSMCs

5.3. Lipid Metabolism Dysregulation and Its Impact on VSMC Function in AAD

5.4. Related Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

5.4.1. AMPK: A Central Metabolic Regulator

5.4.2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and TCA Cycle Metabolites in AAD Pathogenesis

5.4.3. GSDMD–CHOP–ODC1-Putrescine Axis in AAD

5.4.4. HMGB2 and PPARγ Regulation of VSMC Function

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, J.; Cao, H.; Hu, G.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Cui, H.; Lu, H.S.; Zheng, L. The mechanism and therapy of aortic aneurysms. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Du, W.; Ren, L.; Hamblin, M.H.; Becker, R.C.; Chen, Y.E.; Fan, Y. Vascular smooth muscle cells in aortic aneurysm: From genetics to mechanisms. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e023601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halushka, M.K.; Angelini, A.; Bartoloni, G.; Basso, C.; Batoroeva, L.; Bruneval, P.; Buja, L.M.; Butany, J.; d’Amati, G.; Fallon, J.T.; et al. Consensus statement on surgical pathology of the aorta from the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology and the Association for European Cardiovascular Pathology: II. Noninflammatory degenerative diseases—Nomenclature and diagnostic criteria. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2016, 25, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, K.; Zhan, R.; Zhao, M.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Fu, Y.; He, Q.; Tang, P.C.; et al. Untargeted metabolomics identifies succinate as a biomarker and therapeutic target in aortic aneurysm and dissection. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 4373–4385, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 1844–1845. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; LeMaire, S.A.; Shen, Y.H. Programmed cell death in aortic aneurysm and dissection: A potential therapeutic target. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2022, 163, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Zheng, Z.; Ye, W.; Jin, M.; Yang, P.; Little, P.J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z. Targeting the smooth muscle cell KEAP1-Nrf2-STING axis with pterostilbene attenuates abdominal aortic aneurysm. Phytomedicine 2024, 130, 155696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Cifu, A.S.; Vallabhajosyula, P. Management of Thoracic Aortic Dissection. JAMA 2023, 329, 756–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, N.J.; Wu, W.W.; Schermerhorn, M.L. Open and Endovascular Management of Aortic Aneurysms. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xiao, X.; Chang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, H.; Ding, H.; Lu, W.; Li, T.; Tao, Y. Berberine inhibits abdominal aortic aneurysm formation and vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching by regulating the Nrf2 pathway. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Xuan, X.; Hu, J.; Zhang, R.; Jin, H.; Dong, H. How vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype switching contributes to vascular disease. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2022, 20, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, C.M.; Futschik, M.E.; Huang, J.; Bai, W.; Sargurupremraj, M.; Teumer, A.; Breteler, M.M.B.; Petretto, E.; Ho, A.S.R.; Amouyel, P.; et al. Genome-wide associations of aortic distensibility suggest causality for aortic aneurysms and brain white matter hyperintensities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.; Mieremet, A.; de Vries, C.J.M.; Micha, D.; de Waard, V. Six shades of vascular smooth muscle cells illuminated by KLF4 (krüppel-like factor 4). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2693–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Bai, P.; Weng, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Ma, X.; Hu, K.; Sun, A.; Ge, J. Legumain is an endogenous modulator of integrin αvβ3 triggering vascular degeneration, dissection, and rupture. Circulation 2022, 145, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Huang, T.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, Z.; Chi, Y.; Meng, S.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xia, L.; et al. Branched-chain amino acid catabolic defect in vascular smooth muscle cells drives thoracic aortic dissection via mTOR hyperactivation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 210, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.H.; LeMaire, S.A.; Webb, N.R.; Cassis, L.A.; Daugherty, A.; Lu, H.S. Part I: Dynamics of aortic cells and extracellular matrix in aortic aneurysms and dissections. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, e37–e46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khachigian, L.M.; Black, B.L.; Ferdinandy, P.; De Caterina, R.; Madonna, R.; Geng, Y.-J. Transcriptional regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, differentiation and senescence: Novel targets for therapy. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2022, 146, 107091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Li, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, C.; Huang, H. Large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel β1-subunit maintains the contractile phenotype of vascular smooth muscle cells. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1062695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ren, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Xue, L.; Cui, S.; Sang, W.; Xu, T.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; et al. Prevention of aortic dissection and aneurysm via an ALDH2-mediated switch in vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2442–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli-Leonard, F.; Saddic, L.; Aikawa, E. Double-edged sword of ALDH2 mutations: One polymorphism can both benefit and harm the cardiovascular system. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2453–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Fan, W.; Zeng, Q.; Wan, H.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, Z.; Qu, S. The TGF-β pathway plays a key role in aortic aneurysms. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 501, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ren, P.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Azares, A.R.; Zhang, M.; Guo, J.; Ghaghada, K.B.; et al. Critical role of cytosolic DNA and its sensing adaptor STING in aortic degeneration, dissection, and rupture. Circulation 2020, 141, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Rebello, K.R.; Li, S.; Xu, S.; Vasquez, H.G.; Zhang, L.; Luo, W.; et al. Epigenetic induction of smooth muscle cell phenotypic alterations in aortic aneurysms and dissections. Circulation 2023, 148, 959–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Yi, X.; Wei, X.; Huo, B.; Guo, X.; Cheng, C.; Fang, Z.-M.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Zheng, P.; et al. EZH2 inhibits autophagic cell death of aortic vascular smooth muscle cells to affect aortic dissection. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miteva, K. On target inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypic transition underpins TNF-OXPHOS-AP-1 as a promising avenue for anti-remodelling interventions in aortic dissection and rupture. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yi, X.; He, Y.; Huo, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, R.; et al. Targeting Ferroptosis as a Novel Approach to Alleviate Aortic Dissection. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4118–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wu, K. Ferrostatin-1 inhibits ferroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells and alleviates abdominal aortic aneurysm formation through activating the SLC7A11/GPX4 axis. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yi, X.; Huo, B.; He, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, X.; Feng, X.; Fang, Z.-M.; Zhu, X.-H.; et al. BRD4770 functions as a novel ferroptosis inhibitor to protect against aortic dissection. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 106122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, M.; Chappell, J.; Raffort, J.; Lareyre, F.; Vandestienne, M.; Taylor, A.L.; Finigan, A.; Harrison, J.; Bennett, M.R.; Bruneval, P.; et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell plasticity and autophagy in dissecting aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 1149–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganizada, B.H.; Veltrop, R.J.A.; Akbulut, A.C.; Koenen, R.R.; Accord, R.; Lorusso, R.; Maessen, J.G.; Reesink, K.; Bidar, E.; Schurgers, L.J. Unveiling cellular and molecular aspects of ascending thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2024, 119, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Pearce, S.W.A.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Niu, K.; Liu, C.; Luo, J.; Li, D.; Shao, Y.; et al. Causal role for neutrophil elastase in thoracic aortic dissection in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 1900–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo Iniguez, A.; Du, M.; Zhu, M.-J. α-ketoglutarate for preventing and managing intestinal epithelial dysfunction. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Yu, T.; Fu, X. Epigenomics in aortic dissection: From mechanism to therapeutics. Life Sci. 2023, 335, 122249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Lan, Z.; Ye, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liang, Q.; Li, M.; Feng, L.; Chen, A.; Dong, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. The metabolite alpha-ketoglutarate inhibits vascular calcification partially through modulation of TET2/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway. Kidney Int. 2025, 108, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.; Jorgensen, H.F. Epigenetic regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2025, 401, 119085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Espinosa-Diez, C.; Mahan, S.; Du, M.; Nguyen, A.T.; Hahn, S.; Chakraborty, R.; Straub, A.C.; Martin, K.A.; Owens, G.K.; et al. H3K4 di-methylation governs smooth muscle lineage identity and promotes vascular homeostasis by restraining plasticity. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 2765–2782.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xia, C.; Yang, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, R.; Yuan, M. DNA methylation and histone post-translational modifications in atherosclerosis and a novel perspective for epigenetic therapy. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2023, 21, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunstein, M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature 1997, 389, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Tempst, P.; Jones, R.S.; Zhang, Y. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 2002, 298, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, D.; Shankman, L.L.; Nguyen, A.T.; Owens, G.K. Detection of histone modifications at specific gene loci in single cells in histological sections. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, J.L.; Dobnikar, L.; Chappell, J.; Stokell, B.G.; Dalby, A.; Foote, K.; Finigan, A.; Freire-Pritchett, P.; Taylor, A.L.; Worssam, M.D.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Histone H3 Lysine 9 Dimethylation Attenuates Target Gene-Induction by Inflammatory Signaling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 2289–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajuluri, L.P.; Guo, Y.Y.; Lee, S.; Christof, M.; Malhotra, R. Epigenetic regulation of human vascular calcification. Genes 2025, 16, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bure, I.V.; Nemtsova, M.V.; Kuznetsova, E.B. Histone modifications and non-coding RNAs: Mutual epigenetic regulation and role in pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winski, G.; Chernogubova, E.; Busch, A.; Eken, S.M.; Jin, H.; Lindquist Liljeqvist, M.; Khan, T.; Bäcklund, A.; Paloschi, V.; Roy, J.; et al. MicroRNA-15a-5p mediates abdominal aortic aneurysm progression and serves as a potential diagnostic and prognostic circulating biomarker. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhong, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, Y.; Sun, L.; Yuan, A.; Liu, J.; Chen, A.F.; Pu, J. LXRα promotes abdominal aortic aneurysm formation through UHRF1 epigenetic modification of miR-26b-3p. Circulation 2024, 150, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Liu, Y.; Hou, J.; Song, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Ji, Y.; Yan, C.; et al. miR-3154: Novel pathogenic and therapeutic target in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ. Res. 2025, 137, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-L.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.-J.; Shi, M.-M.; Fu, M.-X.; Li, Z.-Q.; Ning, D.-S.; Zeng, X.-M.; Liu, X.; Cui, Q.-H.; et al. Aging aggravates aortic aneurysm and dissection via miR-1204-MYLK signaling axis in mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depuydt, M.A.C.; Prange, K.H.M.; Slenders, L.; Örd, T.; Elbersen, D.; Boltjes, A.; de Jager, S.C.A.; Asselbergs, F.W.; de Borst, G.J.; Aavik, E.; et al. Microanatomy of the Human Atherosclerotic Plaque by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1437–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, W.; Xing, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, H.; Zhao, N.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals differential cell subpopulations and distinct phenotype transition in normal and dissected ascending aorta. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Cho, C.-S.; Liu, H.; Hwang, Y.; Si, Y.; Kim, M.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xue, C.; Guo, Y.; et al. Single-cell spatial transcriptomics unravels the cellular landscape of abdominal aortic aneurysm. JCI Insight 2025, 10, e190534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Du, Y.; Wang, D.; Luo, J.; Yang, P.; Ran, S.; Hu, P.; Chen, M.; et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies interferon-inducible monocytes/macrophages as a cellular target for mitigating the progression of abdominal aortic aneurysm and rupture risk. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Zhu, G.; Yang, H.; Li, W.; Luo, M.; Shu, C.; Zhou, Z. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies an Il1rn+/Trem1+ macrophage subpopulation as a cellular target for mitigating the progression of thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Yang, Z. The pathophysiological role of vascular smooth muscle cells in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cells 2025, 14, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-S.; Yang, R.-R.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, W.-W.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Zu, M.-M.; Gao, Y.-H.; Huo, M.-Q.; Jiang, Y.-T.; Li, B.-Y. Fluoride impairs vascular smooth muscle A7R5 cell lines via disrupting amino acids metabolism. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, J.; Cheng, W.; He, W.; Dai, S.-S. Independent and interactive roles of immunity and metabolism in aortic dissection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, L.; Chen, L. Involvement of the warburg effect in non-tumor diseases processes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 2839–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Mao, C.; Ma, Z.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; Ma, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Yu, F.; Sun, Y.; et al. PHB2 maintains the contractile phenotype of VSMCs by counteracting PKM2 splicing. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, X.; He, X.; Li, X.; Wei, H.; Tan, Y.; Min, J.; Azam, T.; Xue, M.; et al. TRAP1 drives smooth muscle cell senescence and promotes atherosclerosis via HDAC3-primed histone H4 lysine 12 lactylation. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4219–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Fan, X.; Cheng, L.; Chen, Z.; Yi, Y.; Liang, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, N.; Yin, J.; Guo, W.; et al. Metabolism-driven posttranslational modifications and immune regulation: Emerging targets for immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, F.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, T.; Fan, R.; Pei, F.; Luo, S.; et al. GMRSP encoded by lncRNA H19 regulates metabolic reprogramming and alleviates aortic dissection. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.E.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Wu, L.; Chen, H.; Zhu, T.; Lin, J.; Xiong, S.; Wang, Y.; et al. MarcH2 alleviates aortic aneurysm/dissection by regulating PKM2 polymerization. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, e73–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, F.; Williams, H.C.; Quintana, R.A.; San Martin, A. Mitochondrial protein Poldip2 (polymerase delta interacting protein 2) controls vascular smooth muscle differentiated phenotype by O-linked GlcNAc (N-acetylglucosamine) transferase-dependent inhibition of a ubiquitin proteasome system. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.S.; Ryter, S.W.; Plataki, M.; Price, D.R.; Choi, A.M.K. Mitochondria in health, disease, and aging. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 2349–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.-Z.; Li, X.-X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.-T.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.-P.; Yin, M.; Qu, J.; Lei, Q.-Y. Acetylation promotes BCAT2 degradation to suppress BCAA catabolism and pancreatic cancer growth. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Qin, X.; Xiang, M.; Deng, J. PRMT1 upregulates SIRT6 by enhancing arginine methylation of E2F7 to inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell senescence in aortic dissection. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Alonso, A.; Toral, M.; Alfayate, A.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, M.J.; Bonzón-Kulichenko, E.; Teixido-Tura, G.; Martínez-Martínez, S.; Méndez-Olivares, M.J.; López-Maderuelo, D.; González-Valdés, I.; et al. Aortic disease in Marfan syndrome is caused by overactivation of sGC-PRKG signaling by NO. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, I.; He, X.; Liu, J.; Dong, K.; Wen, T.; Zhang, F.; Yu, L.; Hu, G.; Xin, H.; Zhang, W.; et al. TEAD1 (TEA domain transcription factor 1) promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation through upregulating SLC1A5 (solute carrier family 1 member 5)-mediated glutamine uptake. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1309–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, L.; He, L.; Liu, H.; Yang, S.; Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; et al. ANK deficiency-mediated cytosolic citrate accumulation promotes aortic aneurysm. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 1175–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunaga, H.; Matsui, H.; Anjo, S.; Syamsunarno, M.R.A.A.; Koitabashi, N.; Iso, T.; Matsuzaka, T.; Shimano, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Kurabayashi, M. Elongation of long-chain fatty acid family member 6 (Elovl6)-driven fatty acid metabolism regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype through AMP-activated protein kinase/krüppel-like factor 4 (AMPK/KLF4) signaling. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e004014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Li, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chang, F.; Du, J.; Zhang, X.; Bao, K.; Zhang, C.; Shi, L.; et al. Ganglioside GM3 protects against abdominal aortic aneurysm by suppressing ferroptosis. Circulation 2024, 149, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Zarif, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; He, J.; Xie, L.; Wu, Q.; Lin, X.; Chen, K.; Tian, Y.; et al. Hepatic Abnormal Secretion of Apolipoprotein C3 Promotes Inflammation in Aortic Dissection. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e037172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, G.; Cao, X.; Shao, L.; Shen, H.; Guo, X.; Gao, Y.; Su, C.; Fan, H.; Yu, Y.; Shen, Z. Progress and perspectives of metabolic biomarkers in human aortic dissection. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Mechanisms of cellular energy sensing and restoration of metabolic balance. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase ablated the formation of aortic dissection by suppressing vascular inflammation and phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 112, 109177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.-Y.; Lyu, Y.-Y.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Shen, Z.; Lin, G.-Q.; Geng, N.; Wang, Y.-L.; Huang, L.; Feng, Z.-H.; Guo, X.; et al. Nuclear receptor NR1D1 regulates abdominal aortic aneurysm development by targeting the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme aconitase-2. Circulation 2022, 146, 1591–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Han, X.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Qu, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, B. The role of oxidative stress in aortic dissection: A potential therapeutic target. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1410477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branchetti, E.; Poggio, P.; Sainger, R.; Shang, E.; Grau, J.B.; Jackson, B.M.; Lai, E.K.; Parmacek, M.S.; Gorman, R.C.; Gorman, J.H.; et al. Oxidative stress modulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype via CTGF in thoracic aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 100, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavris, B.S.; Peters, A.S.; Böckler, D.; Dihlmann, S. Mitochondrial dysfunction and increased DNA damage in vascular smooth muscle cells of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA-SMC). Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2023, 2023, 6237960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, R.A.; Taylor, W.R. Cellular Mechanisms of Aortic Aneurysm Formation. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.-J.; Sun, J.-Y.; Zhang, W.-C.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lin, W.-Z.; Liu, T.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.-L.; Shao, S.; et al. NCOR1 maintains the homeostasis of vascular smooth muscle cells and protects against aortic aneurysm. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Feng, J.; Zhu, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, S.; Jing, Z.; Zhou, J.; Niu, H.; et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate ameliorates abdominal aortic aneurysm via inhibiting PXDN/HOCL/ERK signaling pathways. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Lv, W.; Zeng, X.; Belosludtsev, K.N.; et al. α-ketoglutarate prevents hyperlipidemia-induced fatty liver mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress by activating the AMPK-pgc-1α/Nrf2 pathway. Redox Biol. 2024, 74, 103230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yesitayi, G.; Liu, B.; Siti, D.; Ainiwan, M.; Aizitiaili, A.; Ma, X. Targeting metabolism in aortic aneurysm and dissection: From basic research to clinical applications. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 3869–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, L.; Huang, F.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, S.; Liu, X. Abstract 2015: Pyruvate carboxylase-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell mitochondrial dysfunction activates cgas-sting signaling in aortic dissection. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, A2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C. Role of Nrf2 and its activators in cardiocerebral vascular disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 4683943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Xu, Y.; Xie, X.; Guo, Y.; Yang, N.; Zhang, X.; et al. Gasdermin D deficiency in vascular smooth muscle cells ameliorates abdominal aortic aneurysm through reducing putrescine synthesis. Adv. Sci. 2022, 10, 2204038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yao, M.; Chen, S.; Li, J.; Wei, X.; Qiu, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L. HMGB2 promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation through PPAR-γ/PGC-1α pathway-mediated glucose changes in aortic dissection. Atherosclerosis 2024, 399, 119044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaigne, D.; Butruille, L.; Staels, B. PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvier, L.; Chouvarine, P.; Legchenko, E.; Hoffmann, N.; Geldner, J.; Borchert, P.; Jonigk, D.; Mozes, M.M.; Hansmann, G. PPARγ links BMP2 and TGFβ1 pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells, regulating cell proliferation and glucose metabolism. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1118–1134.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.-Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhai, W.-H.; Zhao, J.-J.; Yang, Y.-H.; Kang, Y.-Y.; Huang, Q.-F.; Zhang, W.; Rong, W.-W.; Deng, Q.-W.; et al. Deficiency of NPR-C triggers high salt-induced thoracic aortic dissection by impairing mitochondrial homeostasis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Lingala, B.; Baiocchi, M.; Tao, J.J.; Toro Arana, V.; Khoo, J.W.; Williams, K.M.; Traboulsi, A.A.R.; Hammond, H.C.; Lee, A.M.; et al. Type A Aortic Dissection—Experience Over 5 Decades: JACC Historical Breakthroughs in Perspective. JACC 2020, 76, 1703–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, R.O.; Tang, G.H.L.; Barnes, H.J.; Mousavi, I.; Kovacic, J.C.; Faries, P.; Olin, J.W.; Marin, M.L.; Adams, D.H. Optimal Treatment of Uncomplicated Type B Aortic Dissection: JACC Review Topic of the Week. JACC 2019, 74, 1494–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzounian, M.; Tadros, R.O.; Svensson, L.G.; Lyden, S.P.; Oderich, G.S.; Coselli, J.S. Thoracoabdominal aortic disease and repair: JACC focus seminar, part 3. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 845–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalihasan, N.; Limet, R.; Defawe, O.D. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet 2005, 365, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Xie, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, G. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolic Disorders in the Occurrence and Development of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Implications for Therapy. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3072. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123072

Shi Y, Xie X, Sun Y, Chen Y, Chen G. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolic Disorders in the Occurrence and Development of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Implications for Therapy. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3072. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123072

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yuqing, Xianghuan Xie, Yang Sun, Yanghui Chen, and Guangzhi Chen. 2025. "Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolic Disorders in the Occurrence and Development of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Implications for Therapy" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3072. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123072

APA StyleShi, Y., Xie, X., Sun, Y., Chen, Y., & Chen, G. (2025). Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolic Disorders in the Occurrence and Development of Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections: Implications for Therapy. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3072. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123072