Spinal Cord Stimulation in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Advances, Outcomes, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Spinal Cord Stimulation and Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Study Selection

3. Evidence of Clinical Efficacy

3.1. Pain Intensity Reduction (VAS/NRS)—Subjective Outcomes at Short-, Medium-, and Long-Term Follow-Up

3.2. Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC)

3.3. Quality of Life (EQ-5D, EQ VAS) and Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs)

3.4. Sleep Quality—Subjective, Short-, and Medium-Term

3.5. Neurological Function and Sensory Improvement—Objective, Short-, Medium-, and Long-Term

3.6. Peripheral Circulation (PtcO2, ABI, Vasodilation)—Objective, Short- and Medium-Term

3.7. Glucose Control Improvement—Objective, Short-, Medium-, and Long-Term

4. Economic Evaluation of SCS in PDN

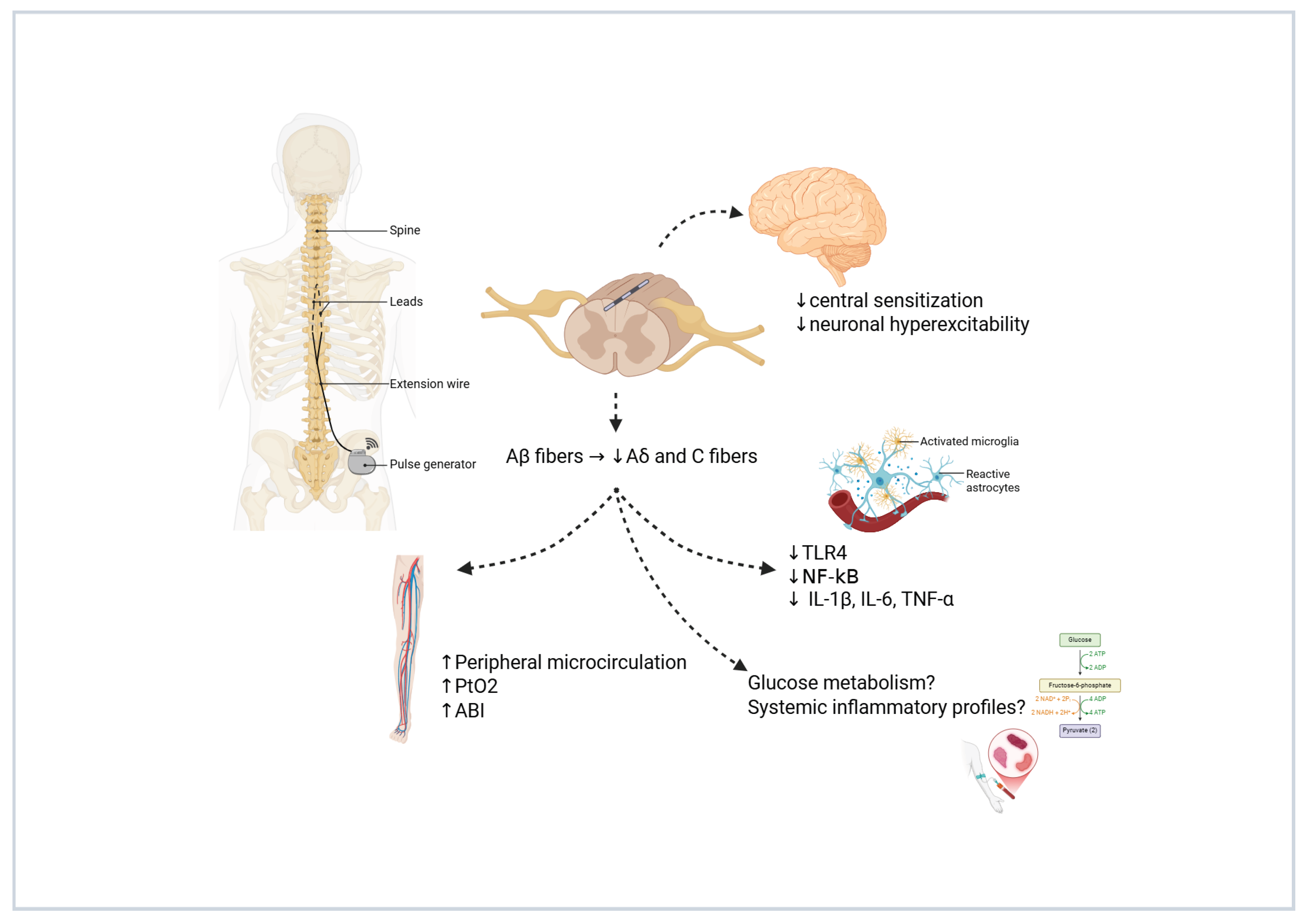

5. Mechanisms of Action and Hypotheses on Spinal Cord Stimulation in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy

6. Patient Selection and Exclusion Criteria for SCS in PDN

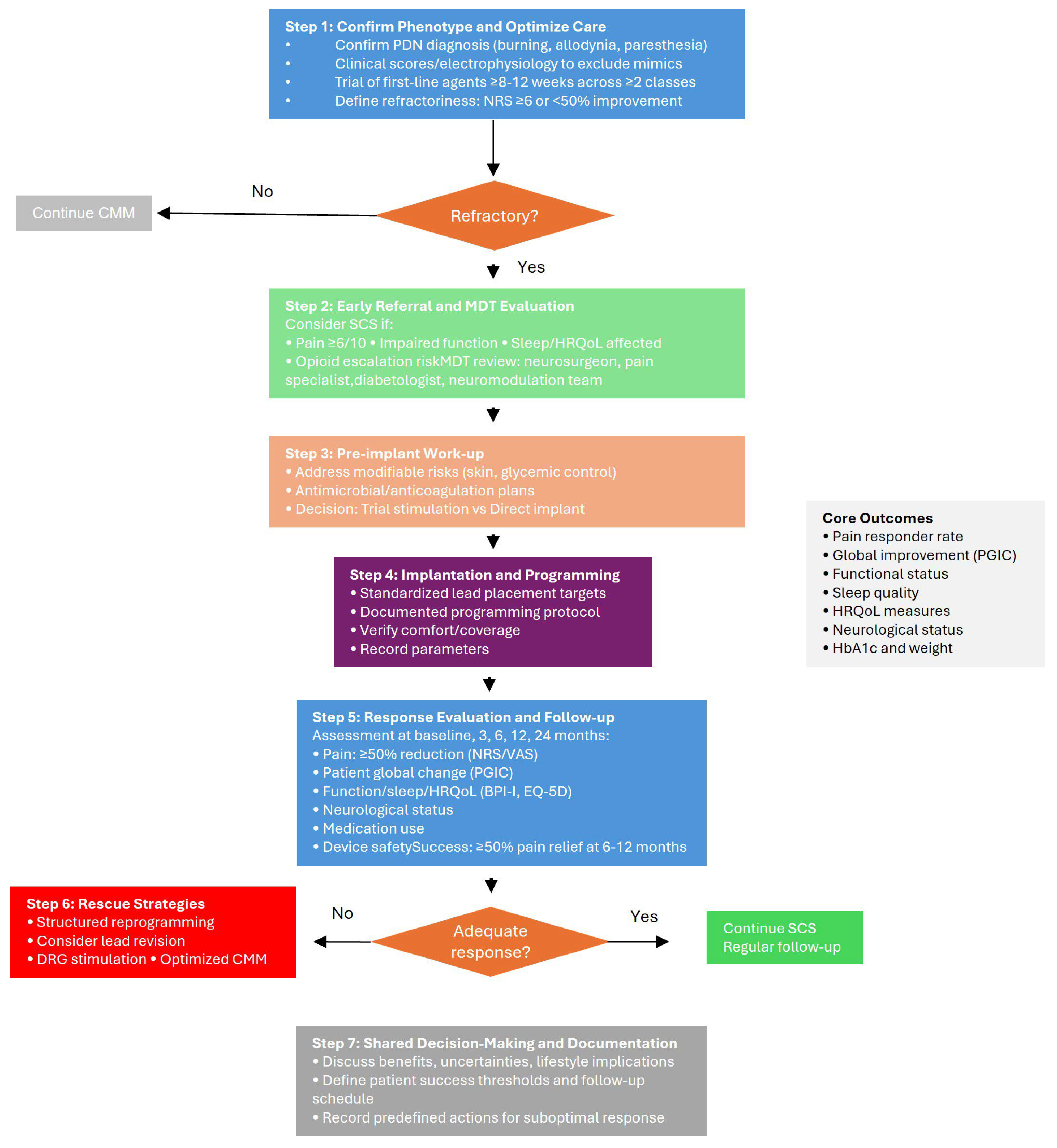

7. Proposed Clinical Decision Algorithm for SCS in Refractory PDN

Proposed Clinical Algorithm for the Management of PDN

- (1)

- Confirm the phenotype and optimize conventional care for a diagnostic confirmation of PDN. Ensure a typical distal symmetric neuropathic pain phenotype (burning, allodynia, paresthesia), supported, when feasible, by clinical scores and/or electrophysiology to exclude mimics (radiculopathy, vasculopathy, entrapment). Optimize CMM documenting a structured trial of first-line agents (e.g., duloxetine, pregabalin/gabapentin, tricyclics as appropriate) and adjuvants (topicals), including dose adequacy, adherence, and tolerability. Then, define refractoriness: persistent moderate–severe pain (e.g., NRS ≥ 6) and/or <50% improvement after adequate CMM (typically ≥8–12 weeks across ≥2 classes) constitutes failure of conservative therapy.

- (2)

- Early referral and multidisciplinary evaluation. Consider SCS referral when (1) pain remains ≥6/10 or function is impaired; (2) sleep/HRQoL are significantly affected; (3) opioid escalation is anticipated or ongoing; (4) neuropathic exam suggests progressive sensory deficits despite CMM. Multidisciplinary review must be performed with neurosurgeon, pain specialist, diabetologist/endocrinologist, and where available a neuromodulation team review to check infection risk, glycemic control, ulceration/foot risk, anticoagulation status, psychological readiness, and realistic expectations (paresthesia-free vs. paresthesia-based paradigms, reprogramming needs).

- (3)

- Pre-implant work-up and choice of implantation strategy. Pre-implant optimization may address modifiable risks (e.g., skin integrity, glycemic control as clinically appropriate) and provide antimicrobial/anticoagulation plans per local policy. Trial stimulation or direct implant must be addressed, selecting a pathway consistent with institutional practice and payer requirements. A short trial stimulation can support shared decision-making in ambiguous cases; single-stage implant may be preferred where trials are not mandated and infection/lead-migration risks weigh against an additional procedure.

- (4)

- Implantation and initial programming. For lead placement and initial programming standardized targets and a documented programming protocol may be used. For paresthesia-free paradigms, verify comfort across common postures; for paresthesia-based paradigms, verify coverage of the painful area. Record initial parameters for reproducibility.

- (5)

- Response evaluation and longitudinal follow-up. Core outcomes should be evaluated at baseline and at follow-up visits occurring approximately at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months (and beyond, where applicable). The assessed domains include the following:

- (a)

- Pain: responder rate (≥50% reduction from baseline) and mean change on NRS or VAS;

- (b)

- Patient-reported global impression of change (PGIC);

- (c)

- Function and interference (e.g., BPI-I), sleep quality, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (e.g., EQ-5D);

- (d)

- Neurological status (e.g., TCNS or MDNS, with optional QST or NCS when feasible);

- (e)

- Concomitant analgesic/opioid use and device-related safety outcomes (e.g., adverse events, lead migration, infection, explantation);

- (f)

- Metabolic and systemic parameters, including HbA1c and body weight/BMI, as exploratory markers of broader health impact.

- (6)

- Reprogramming, rescue strategies, and alternative targets. Stepwise reprogramming should be undertaken when clinical response diminishes. Before labeling a therapy as ineffective, structured reprogramming—including parameter sweeps, waveform adjustments (e.g., tonic, burst, high-frequency), and spatial reconfiguration—should be systematically pursued. If inadequate response persists, lead revision or transition to dorsal root ganglion (DRG) stimulation may be appropriate, particularly in patients with focal or distal pain distributions. In selected phenotypes, combined or sequential stimulation strategies may serve as rescue options.

- -

- Novel antidiabetic agents with potential neuroprotective effects (e.g., GLP-1 receptor agonists, SGLT2 inhibitors, dual incretin agonists);

- -

- Next-generation neuropathic pain therapeutics, such as selective sodium channel blockers (NaV1.7, NaV1.8 inhibitors), anti-NGF antibodies, or gene- and RNA-based analgesic therapies;

- -

- Innovative neuromodulation technologies, including closed-loop or adaptive stimulation platforms.

- (7)

- Shared decision-making and documentation. Discuss expected benefits, uncertainties (e.g., long-term durability, device management), and lifestyle implications (charging/maintenance). Patient-level thresholds for success, follow-up schedule, and predefined actions for suboptimal response to minimize therapeutic drift should be recorded.

8. Complications Associated with SCS: Incidence, Early and Late Events

9. High Prevalence of PDN and Low Rates of SCS Implantation: Challenges and Strategies

10. Future Perspectives in the Management of PDN with SCS

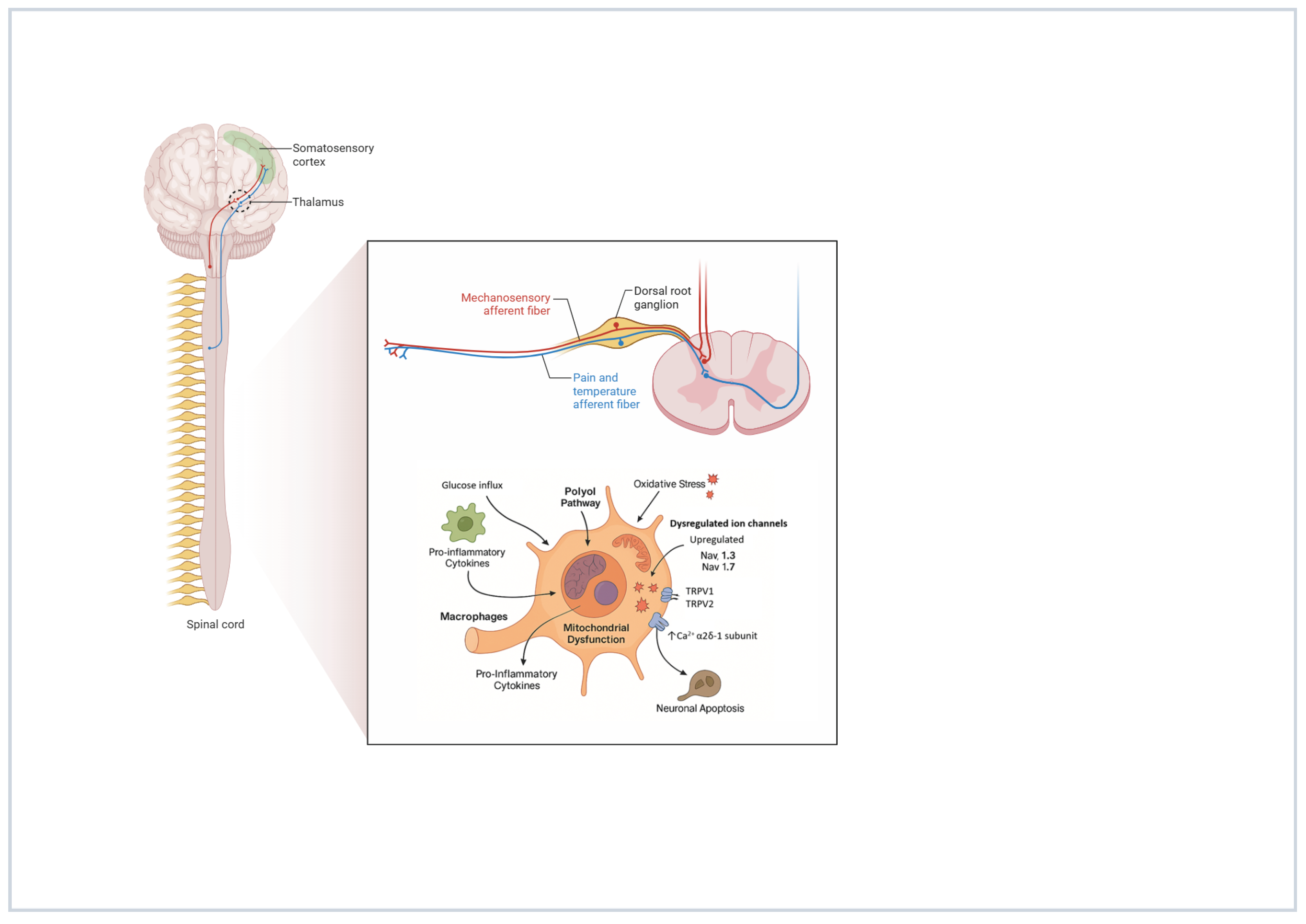

Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) Involvement in PDN: From Pathogenesis to Neuromodulation

11. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABI | Ankle-Brachial Index |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ALA | Alpha-Lipoic Acid |

| ALC | Acetyl-L-Carnitine |

| BMT | Best Medical Treatment |

| CMM | Conventional Medical Management |

| CMP | Conventional Medical Practice |

| CMT | Conventional Medical Therapy |

| DTM | Differential Target Multiplexed |

| DN | Diabetic Neuropathy |

| EQ-5D-5L | EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level Scale |

| EQ VAS | EuroQol Visual Analog Scale |

| GLA | Gamma-Linolenic Acid |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| ICER | Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MDNS | Michigan Diabetic Neuropathy Score |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NNH | Number Needed to Harm |

| NNT | Number Needed to Treat |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-light-chain-enhancer of Activated B cells |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scale |

| PEA | Palmitoylethanolamide |

| PDN | Painful Diabetic Neuropathy |

| PGIC | Patient Global Impression of Change |

| PtcO2 | Transcutaneous Oxygen Pressure |

| QALY | Quality-Adjusted Life Year |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SCS | Spinal Cord Stimulation |

| SNRI | Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor |

| TDC | Traditional Debridement Care |

| TLR4 | Toll-like Receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

References

- Feldman, E.L.; Callaghan, B.C.; Pop-Busui, R.; Zochodne, D.W.; Wright, D.E.; Bennett, D.L.; Bril, V.; Russell, J.W.; Viswanathan, V. Diabetic neuropathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, M.J.; Gibbs, L.M.; Lindsay, T.J. Treating Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: An Update. Am. Fam. Physician 2016, 94, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Lan, H.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Cao, P. Diabetic neuropathy: Cutting-edge research and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zochodne, D.W. Diabetic polyneuropathy: An update. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008, 21, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleman, C.J.M.; Westerhout, K.Y.; Hensen, M.; Chambers, C.; Stoker, M.; Long, S.; van Nooten, F.E. Humanistic and economic burden of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Europe: A review of the literature. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 109, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, N.; Moisset, X.; Ferraro, M.C.; de Andrade, D.C.; Baron, R.; Belton, J.; Bennett, D.L.H.; Calvo, M.; Dougherty, P.; Gilron, I.; et al. Pharmacotherapy and non-invasive neuromodulation for neuropathic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Bell, R.F.; Straube, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Aldington, D.; Moore, R.A. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD007076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Bell, R.F.; Rice, A.S.; Tölle, T.R.; Phillips, T.; Moore, R.A. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD007938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultan, A.; Gaskell, H.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Duloxetine for painful diabetic neuropathy and fibromyalgia pain: Systematic review of randomised trials. BMC Neurol. 2008, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarto, T.; Wiffen, P.J. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 2007, CD005454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, M.; Treadwell, J.R.; Tregear, S.J.; Coates, V.H.; Wiffen, P.J.; Akafomo, C.; Schoelles, K.M. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, CD006605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, M.L.G.; Mercieri, M.; Viswanath, O.; Cascella, M.; Rekatsina, M.; Pasqualucci, A.; Varrassi, G. Neuropathic Pain: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends, Contributions, and Future Directions. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2025, 29, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, G.; Alam, U.; Selvarajah, D.; Tesfaye, S. The Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2022, 18, e070721194556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, R.-Y.; Huang, I.-C.; Chen, C.; Sung, J.-Y. Effects of Oral Alpha-Lipoic Acid Treatment on Diabetic Polyneuropathy: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, E.; Ledermann, H.; Köpcke, W. Benfotiamine in the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy—A three-week randomized, controlled pilot study (BEDIP study). Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 43, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, G.; Di Lionardo, A.; Galosi, E.; Truini, A.; Cruccu, G. Acetyl-L-carnitine in painful peripheral neuropathy: A systematic review. J. Pain Res. 2019, 12, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, U.; Fawwad, A.; Shaheen, F.; Tahir, B.; Basit, A.; Malik, R.A. Improvement in Neuropathy Specific Quality of Life in Patients with Diabetes after Vitamin D Supplementation. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 7928083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, H.; Payan, J.; Allawi, J.; Walker, J.; Jamal, G.A.; Weir, A.I.; Henderson, L.M.; Bissessar, E.A.; Watkins, P.J.; Sampson, M.; et al. Treatment of diabetic neuropathy with gamma-linolenic acid. The gamma-Linolenic Acid Multicenter Trial Group. Diabetes Care 1993, 16, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrassi, G.; Rekatsina, M.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Cascella, M.; Finco, G.; Sardo, S.; Corno, C.; Tiso, D.; Schweiger, V.; Fornasari, D.M.M.; et al. A Decades-Long Journey of Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) for Chronic Neuropathic Pain Management: A Comprehensive Narrative Review. Pain Ther. 2024, 14, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, M.; van Golen, R.F.; Broekgaarden, M.; Michel, M.C. The molecular basis for the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin and its metabolites in relation to cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 222–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuyubamba, O.; Braga, C.P.; Swift, D.; Stickney, J.T.; Viel, C. The Combination of Neurotropic Vitamins B1, B6, and B12 Enhances Neural Cell Maturation and Connectivity Superior to Single B Vitamins. Cells 2025, 14, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Husinat, L.; Obeidat, S.; Azzam, S.; Al-Gwairy, Y.; Obeidat, F.; Al Sharie, S.; Haddad, D.; Haddad, F.; Rekatsina, M.; Leoni, M.L.G.; et al. Role of Cannabis in the Management of Chronic Non-Cancer Pain: A Narrative Review. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, C.C.; Meier, K.; Zaalberg, P.B.; Nijhuis, H.J.A.; Duyvendak, W.; Vesper, J.; Enggaard, T.P.; Lenders, M.W. Spinal cord stimulation in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy: A multicentre randomized clinical trial. Pain 2014, 155, 2426–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slangen, R.; Schaper, N.C.; Faber, C.G.; Joosten, E.A.; Dirksen, C.D.; van Dongen, R.T.; Kessels, A.G.; van Kleef, M. Spinal cord stimulation and pain relief in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A prospective two-center randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 3016–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.A.; Stauss, T.G.; Scowcroft, J.A.; Brooks, E.S.; White, J.L.; Sills, S.M.; Amirdelfan, K.; Guirguis, M.N.; Xu, J.; Yu, C.; et al. Effect of High-frequency (10-kHz) Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients with Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidema, X.; van Daal, E.; van Geel, I.; de Geus, T.J.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; de Galan, B.E.; de Meij, N.; Van Zundert, J. Long-Term Evaluation of Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients with Painful Diabetic Polyneuropathy: An Eight-to-Ten-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Neuromodulation 2023, 26, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.-B.; Sun, H.-T.; Bao, M. Comparative Analysis of the Efficacy of Spinal Cord Stimulation and Traditional Debridement Care in the Treatment of Ischemic Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Neurosurgery 2024, 95, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.V.; Andronis, L.; Lenders, M.W.P.M.; de Vos, C.C. Quality of life increases in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy following treatment with spinal cord stimulation. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canós-Verdecho, Á.; Bermejo, A.; Castel, B.; Izquierdo, R.; Robledo, R.; Gallach, E.; Argente, P.; Peraita-Costa, I.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M. Effects of Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients with Small Fiber and Associated Comorbidities from Neuropathy After Multiple Etiologies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekhail, N.A.; Argoff, C.E.; Taylor, R.S.; Nasr, C.; Caraway, D.L.; Gliner, B.E.; Subbaroyan, J.; Brooks, E.S. High-frequency spinal cord stimulation at 10 kHz for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: Design of a multicenter, randomized controlled trial (SENZA-PDN). Trials 2020, 21, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.A.; Stauss, T.G.; Scowcroft, J.A.; Brooks, E.S.; White, J.L.; Sills, S.M.; Amirdelfan, K.; Guirguis, M.N.; Xu, J.; Yu, C.; et al. Durability of High-Frequency 10-kHz Spinal Cord Stimulation for Patients With Painful Diabetic Neuropathy Refractory to Conventional Treatments: 12-Month Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, e3–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.A.; Stauss, T.G.; Scowcroft, J.A.; Brooks, E.S.; White, J.L.; Sills, S.M.; Amirdelfan, K.; Guirguis, M.N.; Xu, J.; Yu, C.; et al. High-Frequency 10-kHz Spinal Cord Stimulation Improves Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Refractory Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: 12-Month Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2022, 6, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.A.; Stauss, T.G.; Scowcroft, J.A.; Jaasma, M.J.; Brooks, E.S.; Edgar, D.R.; White, J.L.; Sills, S.M.; Amirdelfan, K.; Guirguis, M.N.; et al. Long-term efficacy of high-frequency (10 kHz) spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: 24-Month results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 203, 110865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.S.; Lad, S.P.; White, J.L.; Stauss, T.G.; Healey, B.E.; Sacks, N.C.; McLin, R.; Patil, S.; Jaasma, M.J.; Caraway, D.L.; et al. Health care resource utilization and costs in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy treated with 10 kHz spinal cord stimulation therapy. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2023, 29, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argoff, C.E.; Armstrong, D.G.; Kagan, Z.B.; Jaasma, M.J.; Bharara, M.; Bradley, K.; Caraway, D.L.; Petersen, E.A.; For Investigators. Improvement in Protective Sensation: Clinical Evidence From a Randomized Controlled Trial for Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy With 10 kHz Spinal Cord Stimulation. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2025, 19, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonoff, D.C.; Levy, B.L.; Jaasma, M.J.; Bharara, M.; Edgar, D.R.; Nasr, C.; Caraway, D.L.; Petersen, E.A.; Armstrong, D.G. Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy with 10 kHz Spinal Cord Stimulation: Long-Term Improvements in Hemoglobin A1c, Weight, and Sleep Accompany Pain Relief for People with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Pain Res. 2024, 17, 3063–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.A.; Sills, S.M.; Stauss, T.G.; Province-Azalde, R.; Jaasma, M.J.; Edgar, D.R.; White, J.L.; Scowcroft, J.A.; Yu, C.; Xu, J.; et al. Long-term efficacy of 10 kHz spinal cord stimulation in managing painful diabetic neuropathy: A post-study survey. Pain Pract. 2025, 25, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapural, L.; Yu, C.; Doust, M.W.; Gliner, B.E.; Vallejo, R.; Sitzman, B.T.; Amirdelfan, K.; Morgan, D.M.; Yearwood, T.L.; Bundschu, R.; et al. Novel 10-kHz High-frequency Therapy (HF10 Therapy) Is Superior to Traditional Low-frequency Spinal Cord Stimulation for the Treatment of Chronic Back and Leg Pain: The SENZA-RCT Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2015, 123, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, H.; Sun, K.; Gong, H.J.; Luo, C. Spinal cord stimulation induces Neurotrophin-3 to improve diabetic foot disease. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2025, 58, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, M.; Geurts, J.W.; Slangen, R.; Schaper, N.C.; Faber, C.G.; Joosten, E.A.; Dirksen, C.D.; van Dongen, R.T.; Kessels, A.G.; van Kleef, M. Severity of Neuropathy Is Associated with Long-term Spinal Cord Stimulation Outcome in Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: Five-Year Follow-up of a Prospective Two-Center Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzeri, R.; Occhigrossi, F.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Martino, M.; Schiaffini, R. Therapeutic role of Differential Target Multiplexed (DTM) spinal cord stimulation in painful diabetic neuropathy. Case Rep. Pain Manag. 2025, 15, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, N.H.; Burkey, A.R. Neuromodulation in the Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: A Review of Evidence for Spinal Cord Stimulation. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2022, 16, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, A.L.B.; Parker, T.; Aziz, T.Z.; Green, A.L.; Hadjipavlou, G.; Rea, R.; FitzGerald, J.J. Invasive Electrical Neuromodulation for the Treatment of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuromodulation 2021, 24, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, L.; Terranova, G.; Innamorato, M.A.; Dario, A.; Sofia, M.; Angelini, C.; Duse, G.; Costantini, A.; Leoni, M.L.G. Comparison of Tonic vs. Burst Spinal Cord Stimulation During Trial Period. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y. Spinal Cord Stimulation Alleviates Pain Hypersensitivity by Attenuating Neuroinflammation in a Model of Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2023, 22, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzeri, R.; Castrucci, T.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Mercieri, M.; Occhigrossi, F. Spinal Cord Stimulation for Intractable Chronic Limb Ischemia: A Narrative Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzeri, R.; Mosca, J.; Occhigrossi, F.; Mercieri, M.; Galarza, M.; Leoni, M.L.G. Spinal Cord Stimulation for Refractory Angina Pectoris: Current Status and Future Perspectives, a Narrative Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Bianco, G.; Papa, A.; Schatman, M.E.; Tinnirello, A.; Terranova, G.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Shapiro, H.; Mercadante, S. Practical Advices for Treating Chronic Pain in the Time of COVID-19: A Narrative Review Focusing on Interventional Techniques. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanthanna, H.; Eldabe, S.; Provenzano, D.A.; Bouche, B.; Buchser, E.; Chadwick, R.; Doshi, T.L.; Duarte, R.; Hunt, C.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; et al. Evidence-based consensus guidelines on patient selection and trial stimulation for spinal cord stimulation therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Reg. Anesth. Pain. Med. 2023, 48, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Negri, P.; Paz-Solis, J.F.; Rigoard, P.; Raoul, S.; Kallewaard, J.-W.; Gulve, A.; Thomson, S.; Canós-Verdecho, M.A.; Love-Jones, S.; Williams, A.; et al. Real-world outcomes of single-stage spinal cord stimulation in chronic pain patients: A multicentre, European case series. Interv. Pain Med. 2023, 2, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, R.V.; Thomson, S. Trial Versus No Trial of Spinal Cord Stimulation for Chronic Neuropathic Pain: Cost Analysis in United Kingdom National Health Service. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadwick, R.; McNaughton, R.; Eldabe, S.; Baranidharan, G.; Bell, J.; Brookes, M.; Duarte, R.V.; Earle, J.; Gulve, A.; Houten, R.; et al. To Trial or Not to Trial Before Spinal Cord Stimulation for Chronic Neuropathic Pain: The Patients’ View From the TRIAL-STIM Randomized Controlled Trial. Neuromodulation 2021, 24, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldabe, S.; Nevitt, S.; Griffiths, S.; Gulve, A.; Thomson, S.; Baranidharan, G.; Houten, R.; Brookes, M.; Kansal, A.; Earle, J.; et al. Does a Screening Trial for Spinal Cord Stimulation in Patients with Chronic Pain of Neuropathic Origin Have Clinical Utility (TRIAL-STIM)? 36-Month Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, A.H.; McDonald, C.L.; Basques, B.A.; Hershman, S.H. Perioperative Management of Spinal Cord Stimulators and Intrathecal Pain Pumps. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, e1095–e1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, K.; Catanzaro, J.N.; Elayi, C.; Esquer Garrigos, Z.; Sohail, M.R. Antibiotic-eluting Envelopes to prevent Cardiac-implantable electronic device infection: Past, present and future. Cureus 2021, 13, e13088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J.V.; Varhabhatla, N.C.; Bebic, Z.; Kaye, A.D.; Yong, R.J.; Urman, R.D.; Merkow, J.S. Spinal Cord Stimulation for Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review. Pain Ther. 2021, 10, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco, G.; Al-Kaisy, A.; Natoli, S.; Abd-Elsayed, A.; Matis, G.; Papa, A.; Kapural, L.; Staats, P. Neuromodulation in chronic pain management: Addressing persistent doubts in spinal cord stimulation. J. Anesth. Analg. Crit. Care 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.G.; Bonanno, M.; Manuli, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Improving Outcomes in People with Spinal Cord Injury: Encouraging Results from a Multidisciplinary Advanced Rehabilitation Pathway. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieppo Francio, V.; Polston, K.F.; Murphy, M.T.; Hagedorn, J.M.; Sayed, D. Management of Chronic and Neuropathic Pain with 10 kHz Spinal Cord Stimulation Technology: Summary of Findings from Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Van Buyten, J.-P. 10-kHz High-Frequency SCS Therapy: A Clinical Summary. Pain Med. 2015, 16, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Bayona, S.; Mattar, S.; Arce-Martinez, M.P.; Miranda-Acosta, Y.; Guillen-Burgos, H.F.; Maloof, D. High frequency spinal cord stimulation for chronic back and leg pain. Interdiscip. Neurosurg. 2021, 23, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatheway, J.A.; Mangal, V.; Fishman, M.A.; Kim, P.; Shah, B.; Vogel, R.; Galan, V.; Severyn, S.; Weaver, T.E.; Provenzano, D.A.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy of a Novel Spinal Cord Stimulation Clinical Workflow Using Kilohertz Stimulation: Twelve-Month Results From the Vectors Study. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2021, 24, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.J.; Tavakkolizadeh, M.; Love-Jones, S.; Patel, N.K.; Gu, J.W.; Bains, A.; Doan, Q.; Moffitt, M. Effects of Rate on Analgesia in Kilohertz Frequency Spinal Cord Stimulation: Results of the PROCO Randomized Controlled Trial. Neuromodul. Technol. Neural Interface 2018, 21, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, A.M.; Huang, J.; Nguyen, K.T.; Xu, N.Y.; Hughes, L.T.; Agrawal, B.K.; Ejskjaer, N.; Klonoff, D.C. Spinal Cord Stimulation for Painful Diabetic Neuropathy. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2024, 18, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.Z.; Fishman, M.A. Differential target multiplexed spinal cord stimulator: A review of preclinical/clinical data and hardware advancement. Pain Manag. 2023, 13, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, N.; Torpey, A.; Devitt, C.; Wen, G.A.; Doh, C.; Gupta, A. Closed-Loop Spinal Cord Stimulation in Chronic Pain Management: Mechanisms, Clinical Evidence, and Emerging Perspectives. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cascella, M.; Leoni, M.L.G.; Shariff, M.N.; Varrassi, G. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Diagnostic Processes and Comprehensive Multimodal Models in Pain Medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, V.; Yadav, D.; Patel, S.; Song, M. Effects of a Diabetic Microenvironment on Neurodegeneration: Special Focus on Neurological Cells. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- González, P.; Lozano, P.; Ros, G.; Solano, F. Hyperglycemia and Oxidative Stress: An Integral, Updated and Critical Overview of Their Metabolic Interconnections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hushmandi, K.; Einollahi, B.; Aow, R.; Suhairi, S.B.; Klionsky, D.J.; Aref, A.R.; Reiter, R.J.; Makvandi, P.; Rabiee, N.; Xu, Y.; et al. Investigating the interplay between mitophagy and diabetic neuropathy: Uncovering the hidden secrets of the disease pathology. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 208, 107394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hameed, S. Nav1.7 and Nav1.8: Role in the pathophysiology of pain. Mol. Pain 2019, 15, 1744806919858801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, N.; Ohishi, Y. Molecular Diversity of Structure and Function of the Voltage-Gated Na+ Channels. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 45, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, S.; Sakurai, K.; Shibuya, K.; Isose, S.; Kanai, K.; Ogino, J.; Ishikawa, K.; Kuwabara, S. Neuropathic Pain is Associated with Increased Nodal Persistent Na + Currents in Human Diabetic Neuropathy. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2009, 14, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ta, L.E.; Bieber, A.J.; Carlton, S.M.; Loprinzi, C.L.; Low, P.A.; Windebank, A.J. Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 is Essential for Cisplatin-Induced Heat Hyperalgesia in Mice. Mol. Pain 2010, 6, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.D.; Calcutt, N.A.; Higuera, E.S.; Valder, C.R.; Song, Y.H.; Svensson, C.I.; Myers, R.R. Injury Type-Specific Calcium Channel α2δ-1 Subunit Up-Regulation in Rat Neuropathic Pain Models Correlates with Antiallodynic Effects of Gabapentin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 303, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhave, G.; Hu, H.J.; Glauner, K.S.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H.; Brasier, D.J.; Oxford, G.S.; Gereau, R.W., IV. Protein Kinase C Phosphorylation Sensitizes But Does Not Activate the Capsaicin Receptor Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12480–12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves dos Santos, G.; Delay, L.; Yaksh, T.L.; Corr, M. Neuraxial Cytokines in Pain States. Front. Immunol. 2020, 20, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopmeiners, A.S.; Mueller, S.; Kramer, J.; Hogan, Q.H. Effect of electrical field stimulation on dorsal root ganglion neuronal function. Neuromodulation 2013, 16, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.B.; Sayed, D.; Lamer, T.; Hunter, C.; Weisbein, J.; Patel, K.V.; Dickerson, D.; Hagedorn, J.M.; Lee, D.W.; Amirdelfan, K.; et al. Best Practices for Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation for Chronic Pain: Guidelines from the American Society of Pain and Neuroscience. J. Pain Res. 2023, 16, 839–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eldabe, S.; Espinet, A.; Wahlstedt, A.; Kang, P.; Liem, L.; Patel, N.K.; Vesper, J.; Kimber, A.; Cusack, W.; Kramer, J. Retrospective Case Series on the Treatment of Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy with Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation. Neuromodulation 2018, 21, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franken, G.; Douven, P.; Debets, J.; Joosten, E.A.J. Conventional Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation in an Experimental Model of Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Quantitative Immunocytochemical Analysis of Intracellular γ-Aminobutyric Acid in Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons. Neuromodulation 2021, 24, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Franken, G.; Debets, J.; Joosten, E.A.J. Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation in Experimental Painful Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: Burst vs. Conventional Stimulation Paradigm. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han, Y.F.; Cong, X. Comparison of the efficacy of spinal cord stimulation and dorsal root ganglion stimulation in the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A prospective, cohort-controlled study. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1366796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Author, Year | Journal | Study Design | Sample Size | Primary Outcome | SCS Parameters | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Vos et al. 2014 [23] | Pain | Multicenter randomized clinical trial | 60 patients | ✓ Proportion of patients with 50% pain reduction Primary outcome obtained at 6 months follow-up | ✗ Stimulation parameters not reported. | ✗ High (Lack of blinding for a subjective pain outcome; allocation concealment not clearly reported) |

| Slangen et al. 2014 [24] | Diabetes Care | Prospective two-center randomized controlled trial | 36 patients | ✓ Proportion of patients with 50% pain reduction 59% of SCS patients obtained primary outcome at 6 months follow-up | ✗ Stimulation parameters not reported. | ✗ High (Open-label design with subjective pain outcome and small sample size) |

| Petersen et al. 2021 [25] | JAMA Neurology | Randomized clinical trial | 216 patients | ✓ 50% pain reduction and no deterioration on neurological examination 79% of SCS patients obtained primary outcome at 6 months follow-up | ✓ 10 kHz frequency, 30 μs pulse width delivered via bipole, amplitude range of 0.5 to 3.5 mA | ✗ High (Pain outcome measured without participant/outcome-assessor blinding, despite otherwise strong methodology) |

| Zuidema et al. 2023 [26] | Neuromodulation | Prospective cohort study | 19 patients | ✓ Pain intensity reduction (day and night) >50% of patients, the pain reduction was >30% at eight-to-ten-year follow-up | ✓ Bipool configuration, pulse width 150–450 μm. Fewer differences were present in stimulation frequency, with most (65%) patients frequency of 30 Hz, although higher frequencies up to 60 Hz were also used. | ✗ Critical (Uncontrolled confounding; no randomized comparator) |

| Zhou et al. 2024 [27] | Neurosurgery | Retrospective cohort study | 141 patients | ✓ Comparison of amputation rates between SCS and TDC groups. Odds of amputation at 12 months: OR = 0.17 (95% CI, 0.08–0.37) | ✓ Voltage, 0.5 V; pulse width, 180–240 μs; frequency, 40 Hz | ◐ Serious (Treatment allocation based on patient preference; limited statistical adjustment) |

| Duarte et al. 2016 [28] | Quality of Life Research | Multicenter randomized controlled trial | 60 patients (CMP = 20, SCS = 40) | ✓ SCS vs. CMP at 6 months (QALY gain) QALY gain—adjusted for baseline EQ-5D score = 0.258 | ✗ Stimulation parameters not reported. | ✗ High (Shares the parent trial’s lack of blinding; quality-of-life outcome self-reported) |

| Canós-Verdecho et al. 2025 [29] | Journal Clinical Medicine | Prospective observational cohort study | 20 patients (6DPN) | ◐ Pain intensity reduction and potential small fiber re-growth | ✓ Combination of paresthesia-based stimulation and Contour© (50 Hz, ~300 μs pulse-width, ~40% of perception threshold), or FAST (90 Hz frequency, ~250 μs pulse-wid, 40% of perception threshold) | ◐ Serious (non-randomized; small N; mixed etiologies) |

| Author, Year | Journal | Study Type | Dataset Phase | Sample Size | Follow Up | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mekhail, 2020 [30] | Trials | Trial protocol/design (SENZA-PDN RCT) | Design | Planned RCT; design paper | Describes 3–6 months primary, longer-term extensions | Protocol for RCT comparing 10 kHz SCS + CMM vs. CMM in refractory PDN |

| Petersen, 2021 [25] | JAMA Neurology | Randomized clinical trial (primary outcomes) | Randomization | 216 randomized; 187 assessed at 6 months | Primary endpoint at 3 months; 6-months randomized phase | ≥50% pain relief: 85% SCS vs. 5% CMM at 6 months; HRQoL and sleep improved; acceptable safety |

| Petersen, 2022 [31] | Diabetes Care | RCT follow-up | 12 months | Original SCS: 84; CMM → SCS crossover: 58 | 12 months | Durable pain relief; high responder rates; neurological improvement persists; crossover similar after implant |

| Petersen, 2022 [32] | Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes | RCT outcomes analysis (patient-centered outcomes) | 12 months | RCT cohort | 12 months | HRQoL (EQ-5D) and satisfaction improved alongside large pain reductions |

| Petersen, 2023 [33] | Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice | RCT extended outcomes | 24 months | 142 with SCS (84 initial + 58 crossover) | 24 months | Mean pain −79.9%; 90.1% ≥50% relief; 65.7% neurological improvement; HRQoL and sleep improved; 3.2% explants (infection) |

| Taylor, 2023 [34] | J Manag Care Spec Pharm | Health economics/utilization (RCT) | 0–6 months randomized phase | RCT resource-use dataset | 6 months (annualized costs) | Lower hospitalizations and total healthcare costs with 10 kHz SCS + CMM vs. CMM |

| Argoff, 2025 [35] | J Diabetes Sci Technol | Subanalysis: protective sensation/ulceration risk | 3-, 6-, 12-, 24-months assessments | RCT cohort incl. crossover | Up to 24 months | More sensate monofilament sites; low-risk ulceration class roughly doubled by 3 months and sustained to 24 months |

| Klonoff, 2024 [36] | Journal of Pain Research | Post hoc subanalysis: metabolic and sleep outcomes | 24 months | SENZA-PDN participants with T2D | 24 months | HbA1c and body weight reduced (largest in higher baseline HbA1c/BMI); sleep interference reduced |

| Petersen, 2025 [37] | Pain Practice | Post-study survey (real-world, long-term) | ≈4.1 years post-implant | Implanted SENZA-PDN patients (survey) | ≈4.1 years | Sustained pain relief and HRQoL; no explants for loss of efficacy; weight and HbA1c reductions vs. 24 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gazzeri, R.; Mosca, J.; Occhigrossi, F.; Galarza, M.; Schiaffini, R.; Varrassi, G.; Mercieri, M.; Leoni, M.L.G. Spinal Cord Stimulation in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Advances, Outcomes, and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123063

Gazzeri R, Mosca J, Occhigrossi F, Galarza M, Schiaffini R, Varrassi G, Mercieri M, Leoni MLG. Spinal Cord Stimulation in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Advances, Outcomes, and Future Directions. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123063

Chicago/Turabian StyleGazzeri, Roberto, Jacopo Mosca, Felice Occhigrossi, Marcelo Galarza, Riccardo Schiaffini, Giustino Varrassi, Marco Mercieri, and Matteo Luigi Giuseppe Leoni. 2025. "Spinal Cord Stimulation in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Advances, Outcomes, and Future Directions" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123063

APA StyleGazzeri, R., Mosca, J., Occhigrossi, F., Galarza, M., Schiaffini, R., Varrassi, G., Mercieri, M., & Leoni, M. L. G. (2025). Spinal Cord Stimulation in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: Advances, Outcomes, and Future Directions. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3063. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123063