Cutaneous Adverse Events of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Endocrine Tumors: Clinical Features, Mechanisms, and Management Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction and Scope of the Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Design

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Definitions and Grading

2.7. Synthesis Approach

2.8. Ethics

3. Background

4. Major Manifestations

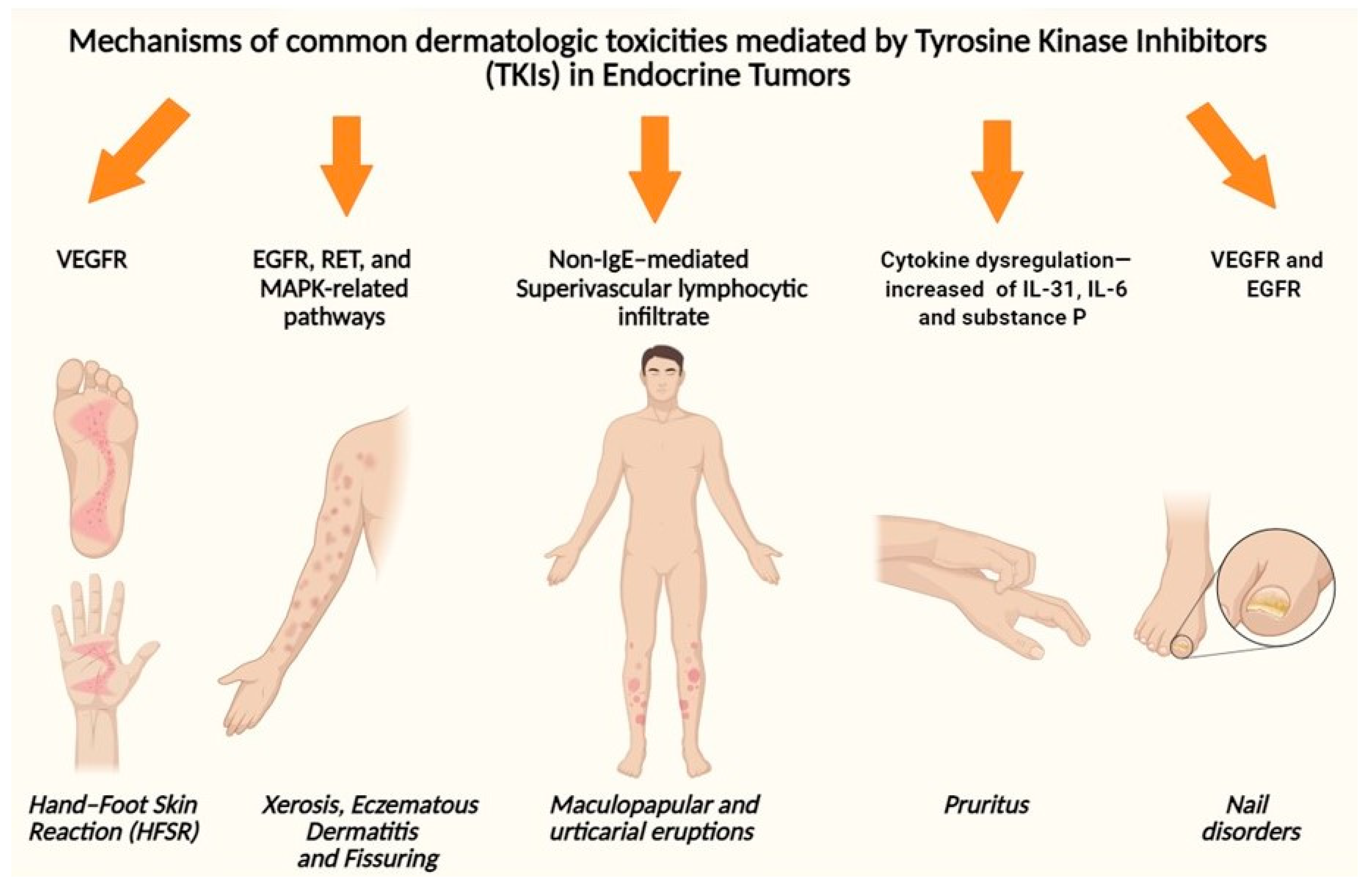

4.1. Hand–Foot Skin Reaction (HFSR)

4.2. Xerosis, Eczematous Dermatitis, and Fissuring

4.3. Maculopapular and Urticarial Eruptions

4.4. Pruritus

4.5. Nail Disorders and Paronychia

5. Rare but Severe Events

5.1. Stevens–Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

5.2. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia

5.3. Cutaneous Small-Vessel Vasculitis

6. Main Pathogenetic Mechanisms of TKI-Related CAEs

7. Differential Diagnosis and Clinical Workflow

8. Practical Management by Manifestation and Dose-Modification Principles

8.1. Management of HFSR

8.2. Management of Xerosis and Eczematous Dermatitis

8.3. Management of Maculopapular Eruptions

8.4. Management of Pruritus

8.5. Management of Paronychia and Nail Disorders

8.6. Management of Hair Disorders

8.7. Management of Pigmentary Changes and Photosensitivity

8.8. Management of Mucositis

8.9. Management of Severe or Life-Threatening CAEs

9. Conclusions and Key Messages

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boucai, L.; Zafereo, M.; Cabanillas, M.E. Thyroid Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siebenhüner, A.R.; Refardt, J.; Nicolas, G.P.; Kaderli, R.; Walter, M.A.; Perren, A.; Christ, E. Impact of multikinase inhibitors in reshaping the treatment of advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2025, 32, e250052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leo, A.; Di Simone, E.; Spano, A.; Puliani, G.; Petrone, F. Nursing Management and Adverse Events in Thyroid Cancer Treatments with Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. A Narrative Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, T.J.; Wirth, L.J. Management of Adverse Events During Treatment for Advanced Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2025, 35, 716–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, P.; Ferrari, S.M.; Galdiero, M.R.; Varricchi, G.; Elia, G.; Ragusa, F.; Paparo, S.R.; Benvenga, S.; Antonelli, A. Molecular targets of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in thyroid cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 79, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, T.; Chino, T.; Soma, A.; Shimizu, T.; Ono, M.; Ito, T.; Kanai, T.; Maeno, K.; Ito, K.-I. Comparative efficacy and safety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for thyroid cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr. J. 2020, 67, 1215–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, Q.; Wang, J.; Tan, Z.; Li, Q.; Ge, M. Molecular basis and targeted therapy in thyroid cancer: Progress and opportunities. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 188928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosalem, O.; Sonbol, M.B.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Starr, J.S. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Immunotherapy Updates in Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 37, 101796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, F.; Giani, C.; Cobellis, G. The Role of the Kinase Inhibitors in Thyroid Cancers. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puliafito, I.; Esposito, F.; Prestifilippo, A.; Marchisotta, S.; Sciacca, D.; Vitale, M.P.; Giuffrida, D. Target Therapy in Thyroid Cancer: Current Challenge in Clinical Use of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Management of Side Effects. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 860671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.T.; Haap, M.; Kopp, H.-G.; Lipp, H.-P. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors—A Review on Pharmacology, Metabolism and Side Effects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009, 10, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resteghini, C.; Cavalieri, S.; Galbiati, D.; Granata, R.; Alfieri, S.; Bergamini, C.; Bossi, P.; Licitra, L.; Locati, L. Management of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) side effects in differentiated and medullary thyroid cancer patients. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 31, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Onoda, N.; Kudo, T.; Masuoka, H.; Higashiyama, T.; Kihara, M.; Miya, A.; Miyauchi, A. Sorafenib and Lenvatinib Treatment for Metastasis/Recurrence of Radioactive Iodine-refractory Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma. In Vivo 2021, 35, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlumberger, M.; Tahara, M.; Wirth, L.J.; Robinson, B.; Brose, M.S.; Elisei, R.; Habra, M.A.; Newbold, K.; Shah, M.H.; Hoff, A.O.; et al. Lenvatinib versus Placebo in Radioiodine-Refractory Thyroid Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerkovich, F.; Capalbo, S.; Abelleira, E.; Pitoia, F. Ten years’ real-life experience on the use of multikinase inhibitors in patients with advanced differentiated thyroid cancer. Endocrine 2024, 85, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.M.; Patrizio, A.; Stoppini, G.; Elia, G.; Ragusa, F.; Balestri, E.; Botrini, C.; Rugani, L.; Barozzi, E.; Mazzi, V.; et al. Recent advances in the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors against thyroid cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Califano, I.; Randolph, G.W.; Pitoia, F. Transforming thyroid cancer management: The impact of neoadjuvant therapy. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2025, 32, e240185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond, E.; Hobday, T.; Castellano, D.; Reidy-Lagunes, D.; García-Carbonero, R.; Carrato, A. Therapy innovations: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011, 30 (Suppl. S1), 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, E.L.; Olamiju, B.; Leventhal, J.S. Potentially life-threatening severe cutaneous adverse reactions associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2021, 45, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, R.C.; Apolo, A.B.; DiGiovanna, J.J.; Parnes, H.L.; Keen, C.M.; Nanda, S.; Dahut, W.L.; Cowen, E.W. Cutaneous adverse effects associated with the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor cabozantinib. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, P.R.; Okman, J.S.; Wilkerson, J.; Cowen, E.W. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors directed against the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) have distinct cutaneous toxicity profiles: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, G.W.; Mani, R.M.; Jaffry, A.; Khan, S.A. Toxic effects of sorafenib in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma compared with other cancers. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shou, L.; Chen, J.; Shao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Chen, S.; Shu, Q. Clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and prognosis in patients with MKIs-associated hand-foot skin reaction: A retrospective study. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Ciccolini, K.; Kloos, R.T.; Agulnik, M. Overview and Management of Dermatologic Events Associated with Targeted Therapies for Medullary Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2014, 24, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v.5.0. Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. 2017. Available online: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Cheng, L.; Fu, H.; Jin, Y.; Sa, R.; Chen, L. Clinicopathological Features Predict Outcomes in Patients with Radioiodine-Refractory Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Treated with Sorafenib: A Real-World Study. Oncologist 2020, 25, e668–e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.; Belum, V.R.; Duran, J.; Ciccolini, K.; Schindler, K.; Wu, S.; Lacouture, M.E. Incidence and risk of xerosis with targeted anticancer therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, R.S.; Aad, S.A.; Kyei, A.; Farhat, F.S. Cutaneous manifestations of anti-angiogenic therapy in oncology: Review with focus on VEGF inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2014, 90, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Mateus, C.; Spatz, A.; Wechsler, J.; Escudier, B. Dermatologic symptoms associated with the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009, 60, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Habito, C.M.; Roh, E.K. Cutaneous reactions to chemotherapeutic drugs and targeted therapy for cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 217.e1–217.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lacouture, M.E. Pruritus Associated with Targeted Anticancer Therapies and Their Management. Dermatol. Clin. 2018, 36, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enokida, T.; Tahara, M. Management of VEGFR-Targeted TKI for Thyroid Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Sibaud, V.; Mateus, C.; Verschoore, M.; Charles, C.; Lanoy, E.; Baran, R. Nail toxicities induced by systemic anticancer treatments. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e181–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.P. Nail toxicity associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor therapy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 56, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, M.; Sibaud, V. Toxic Side Effects of Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies Affecting the Skin, Oral Mucosa, Hair, and Nails. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 19, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, H.L.B.; Pacha, O.; Heberton, M.; Patel, A.B. Surgical Intervention for Paronychia Induced by Targeted Anticancer Therapies. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, M.L.; Abad, C.; Kurtzman, Y.; Abdulla, F.R. Dermatologic Toxicities of Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 605941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemer, M.; Fries, V.; Paulmann, M.; Mockenhaupt, M. Epidermal necrolysis in the context of immuno-oncologic medication as well as kinase inhibitors and biologics. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG 2022, 20, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, A.C.; Balagula, Y.; Raisch, D.W.; Garg, V.; Nardone, B.; Larsen, N.; Sorrell, J.; West, D.P.; Anadkat, M.J.; Lacouture, M.E. Life-threatening dermatologic adverse events in oncology. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2014, 25, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroshinsky, D.; Cardones, A.R.G.; Blumenthal, K.G. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2242–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Goh, M.S.; Trubiano, J.A. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: A Systematic Review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 1856–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.M.; Fox, L.P.; Kaffenberger, B.H.; Korman, A.M.; Micheletti, R.G.; Mostaghimi, A.; Noe, M.H.; Rosenbach, M.; Shinkai, K.; Kwah, J.H.; et al. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome/drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. Part I. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinicopathological features, and prognosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 885–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santorsola, M.; Capuozzo, M.; Nasti, G.; Sabbatino, F.; Di Mauro, A.; Di Mauro, G.; Vanni, G.; Maiolino, P.; Correra, M.; Granata, V.; et al. Exploring the Spectrum of VEGF Inhibitors’ Toxicities from Systemic to Intra-Vitreal Usage in Medical Practice. Cancers 2024, 16, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ak, T.; Durmus, R.B.; Onel, M. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with molecular tergeted therapies: Systematic review of the literature. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 42, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, A.K.; Balagula, Y. Drug-induced cutaneous vasculitis and anticoagulant-related cutaneous adverse reactions: Insights in pathogenesis, clinical presentation, and treatment. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 38, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Cheng, L.; Li, C.; Lv, D.; Xia, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Nitric oxide in multikinase inhibitor-induced hand-foot skin reaction. Transl. Res. 2022, 245, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, N.; Takahashi, S. Clinical Indications for Treatment with Multi-Kinase Inhibitors in Patients with Radioiodine-Refractory Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celoria, V.; Rosset, F.; Pala, V.; Dapavo, P.; Ribero, S.; Quaglino, P.; Mastorino, L. The Skin Microbiome and Its Role in Psoriasis: A Review. Psoriasis 2023, 13, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibaud, V. Anticancer treatments and photosensitivity. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36 (Suppl. S6), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandpur, S.; Porter, R.; Boulton, S.; Anstey, A. Drug-induced photosensitivity: New insights into pathomechanisms and clinical variation through basic and applied science. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, J.; Rok, J.; Rzepka, Z.; Wrześniok, D. Drug-Induced Photosensitivity—From Light and Chemistry to Biological Reactions and Clinical Symptoms. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.H.; Masuo, Y.; Fujita, K.-I.; Shimada, K.; Iida, N.; Wakayama, T.; Kato, Y. Discrimination of hand-foot skin reaction caused by tyrosine kinase inhibitors based on direct keratinocyte toxicity and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 inhibition. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 197, 114914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-T.; Yang, C.-W.; Chu, C.-Y. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS): An Interplay among Drugs, Viruses, and Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Reilly, L.M.; Gerami, P.; Guitart, J. Hand foot skin reaction in cancer patients treated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1955–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, R.T.; Fiorentino, D.F.; Chung, L.; Robinson, W.H. Tyrosine kinases in inflammatory dermatologic disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llamas-Velasco, M.; Ovejero-Merino, E.; García-Diez, A.; Requena, L.; Daudén, E.; Steegmann, J.L. Cutaneous side effects in a cohort of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: General description and further characterization, correlation with photoexposition and study of hypopigmentation as treatment’s prognostic factor. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandy, J.G.P.; Franco, P.I.G.; Li, R.K. Prophylactic strategies for hand-foot syndrome/skin reaction associated with systemic cancer treatment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 8655–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Jung, Y.K.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, S.B.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Seo, Y.S.; Yoon, K.T.; Hong, Y.M.; et al. Effect of urea cream on sorafenib-associated hand–foot skin reaction in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter, randomised, double-blind controlled study. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 140, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhu, K.; Kang, H.; Lu, M.; Qu, Z.; Lu, L.; Song, T.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, W.; et al. Randomized controlled trial of the prophylactic effect of urea-based cream on sorafenib-associated hand-foot skin reactions in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestergaard, C.; Torrelo, A.; Christen-Zaech, S. Clinical Benefits of Basic Emollient Therapy for the Management of Patients with Xerosis Cutis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepietowski, J.C.; Tadini, G. Basic Emollients for Xerosis Cutis Not Associated with Atopic Dermatitis: A Review of Clinical Studies. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, A.; Barbarot, S.; Torrelo, A. Basic Emollients for Xerosis Cutis in Atopic Dermatitis: A Review of Clinical Studies. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jfri, A.; Meltzer, R.; Mostaghimi, A.; LeBoeuf, N.; Guggina, L. Incidence of Cutaneous Adverse Events with Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Inhibitors as Adjuvant Therapy in Patients with Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broyles, A.D.; Banerji, A.; Barmettler, S.; Biggs, C.M.; Blumenthal, K.; Brennan, P.J.; Breslow, R.G.; Brockow, K.; Buchheit, K.M.; Cahill, K.N.; et al. Practical Guidance for the Evaluation and Management of Drug Hypersensitivity: Specific Drugs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, S16–S116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, R.S. Exanthematous Drug Eruptions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 2492–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.C.; Berger, T.; Elmariah, S.; Kim, B.; Chisolm, S.; Kwatra, S.G.; Mollanazar, N.; Yosipovitch, G. Chronic Pruritus. JAMA 2024, 331, 2114–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Woo, J.; Kim, T.M.; Kim, N.; Keam, B.; Jo, S.J. Skin Toxicities Induced by Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and their Influence on Treatment Adjustments in Lung Cancer Patients. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2024, 104, adv40555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masago, K.; Irie, K.; Fujita, S.; Imamichi, F.; Okada, Y.; Katakami, N.; Fukushima, S.; Yatabe, Y. Relationship between Paronychia and Drug Concentrations of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Oncology 2018, 95, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, L.-C.; Chen, K.-H.; Wang, C.-L.; Weng, L.-C. Effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy on skin toxicity and skin-related quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Medicine 2020, 99, e20510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kang, J.; Choi, J.Y.; Hong, K.T.; Kang, H.J.; Kwon, O. Topical minoxidil and dietary supplement for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced alopecia in childhood: A retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiska, Y.M.; Mirmirani, P.; Roseborough, I.; Mathes, E.; Bhutani, T.; Ambrosy, A.; Aguh, C.; Bergfeld, W.; Callender, V.D.; Castelo-Soccio, L.; et al. Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil Initiation for Patients with Hair Loss. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freites-Martinez, A.; Shapiro, J.; Goldfarb, S.; Nangia, J.; Jimenez, J.J.; Paus, R.; Lacouture, M.E. Hair disorders in patients with cancer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, V.H. Management of treatment-related toxicities in advanced medullary thyroid cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüggen, M.-C.; Walsh, S.; Ameri, M.M.; Anasiewicz, N.; Maverakis, E.; French, L.E.; Ingen-Housz-Oro, S.; DRESS Delphi Consensus Group; Abe, R.; Ardern-Jones, M.; et al. Management of Adult Patients with Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms: A Delphi-Based International Consensus. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lesion | Main Mechanisms | Typical Time to Onset | Proposed Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand–Foot Skin Reaction (HFSR) | VEGFR/PDGFR inhibition → impaired dermal microcirculation; mechanical stress on pressure areas. | 2–6 weeks after initiation. | Prophylaxis with emollients/urea 10–20% and keratolytics; mechanical off-loading; potent topical corticosteroids; salicylic acid for hyperkeratosis; topical anesthetics; selective debridement; for grade 3: temporary hold and restart at reduced dose. |

| Xerosis/eczematous dermatitis/fissures | Barrier dysfunction due to EGFR/RET/MAPK inhibition → reduced proliferation/lipid synthesis, ↑TEWL. | Early, often persistent/cumulative (first weeks–months). | Lipid-rich emollients (ceramides/urea/glycerin) ≥ 2/day; avoid irritants; class II–III topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors in sensitive areas; barrier dressings for fissures; topical/systemic antibiotics if superinfection. |

| Maculopapular eruption | Epidermal–dermal inflammation from altered signaling; typically, non–IgE mediated. | Usually within the first month. | Medium-potency topical corticosteroids + antihistamines; in grade ≥ 2 short courses of systemic corticosteroids; temporary interruption if severe/atypical; biopsy if diagnostic doubt. |

| Pruritus (with or without lesions) | Cytokines (e.g., IL-31), neurogenic inflammation, peripheral fiber damage; barrier dysfunction; possible neuropathic component. | Early or late; fluctuating course. | Intensive hydration; antihistamines (esp. at night); soothing topicals (menthol/pramoxine); consider gabapentinoids if refractory; rule out systemic causes (hepatic/renal). |

| Paronychia/nail disorders | Altered keratinocyte proliferation and periungual repair; microtrauma; VEGFR/EGFR involvement. | After several weeks of therapy. | Mechanical protection; antiseptic soaks (diluted vinegar/chlorhexidine); topical corticosteroids; silver nitrate for granulation; antibiotics/antimycotics if infection; laser/selective debridement; hold/dose reduction if severe. |

| Photosensitivity/pigmentary changes | Drug–UV interaction and epidermal dysfunction; reported with EGFR/RET inhibitors (e.g., vandetanib). | Variable; often with UV exposure during treatment. | Strict photoprotection (SPF ≥ 50, physical barriers, behavior); topical corticosteroids for phototoxic reactions; camouflage/depigmenting agents if needed; avoid UV until resolution. |

| Oral mucositis/cheilitis/stomatitis | Mucosal toxicity with multikinase inhibitors; altered mucosal barrier. | Variable; may impair oral intake. | Oral hygiene + bland rinses (saline/bicarbonate); barrier agents (dexpanthenol); topical anesthetics; short course of corticosteroids; systemic analgesics; hold TKI if severe. |

| Severe reactions (SJS/TEN; DRESS) | T cell–mediated hypersensitivity with keratinocyte apoptosis (SJS/TEN) or systemic immune response (DRESS). | DRESS 2–8 weeks; SJS/TEN often rapid with systemic symptoms. | Definitive TKI discontinuation; management in specialized setting; intensive support; immunomodulation (corticosteroids, IVIG, cyclosporine) as per protocols; re-challenge generally contraindicated. |

| Small-vessel cutaneous vasculitis | Leukocytoclastic vasculitis; reported with VEGFR inhibitors. | Variable; palpable purpura on lower limbs. | TKI discontinuation; systemic corticosteroids if extensive/systemic involvement; avoid re-challenge. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marino, M.; Rosset, F.; Nervo, A.; Piovesan, A.; Pala, V.; Vaccaro, E.; Mastorino, L.; Calogero, A.E.; Arvat, E. Cutaneous Adverse Events of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Endocrine Tumors: Clinical Features, Mechanisms, and Management Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123044

Marino M, Rosset F, Nervo A, Piovesan A, Pala V, Vaccaro E, Mastorino L, Calogero AE, Arvat E. Cutaneous Adverse Events of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Endocrine Tumors: Clinical Features, Mechanisms, and Management Strategies. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123044

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarino, Marta, Francois Rosset, Alice Nervo, Alessandro Piovesan, Valentina Pala, Elisa Vaccaro, Luca Mastorino, Aldo E. Calogero, and Emanuela Arvat. 2025. "Cutaneous Adverse Events of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Endocrine Tumors: Clinical Features, Mechanisms, and Management Strategies" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123044

APA StyleMarino, M., Rosset, F., Nervo, A., Piovesan, A., Pala, V., Vaccaro, E., Mastorino, L., Calogero, A. E., & Arvat, E. (2025). Cutaneous Adverse Events of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Endocrine Tumors: Clinical Features, Mechanisms, and Management Strategies. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3044. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123044