Analysis Methods for Diagnosing Rare Neurodevelopmental Diseases with Episignatures: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Abstract

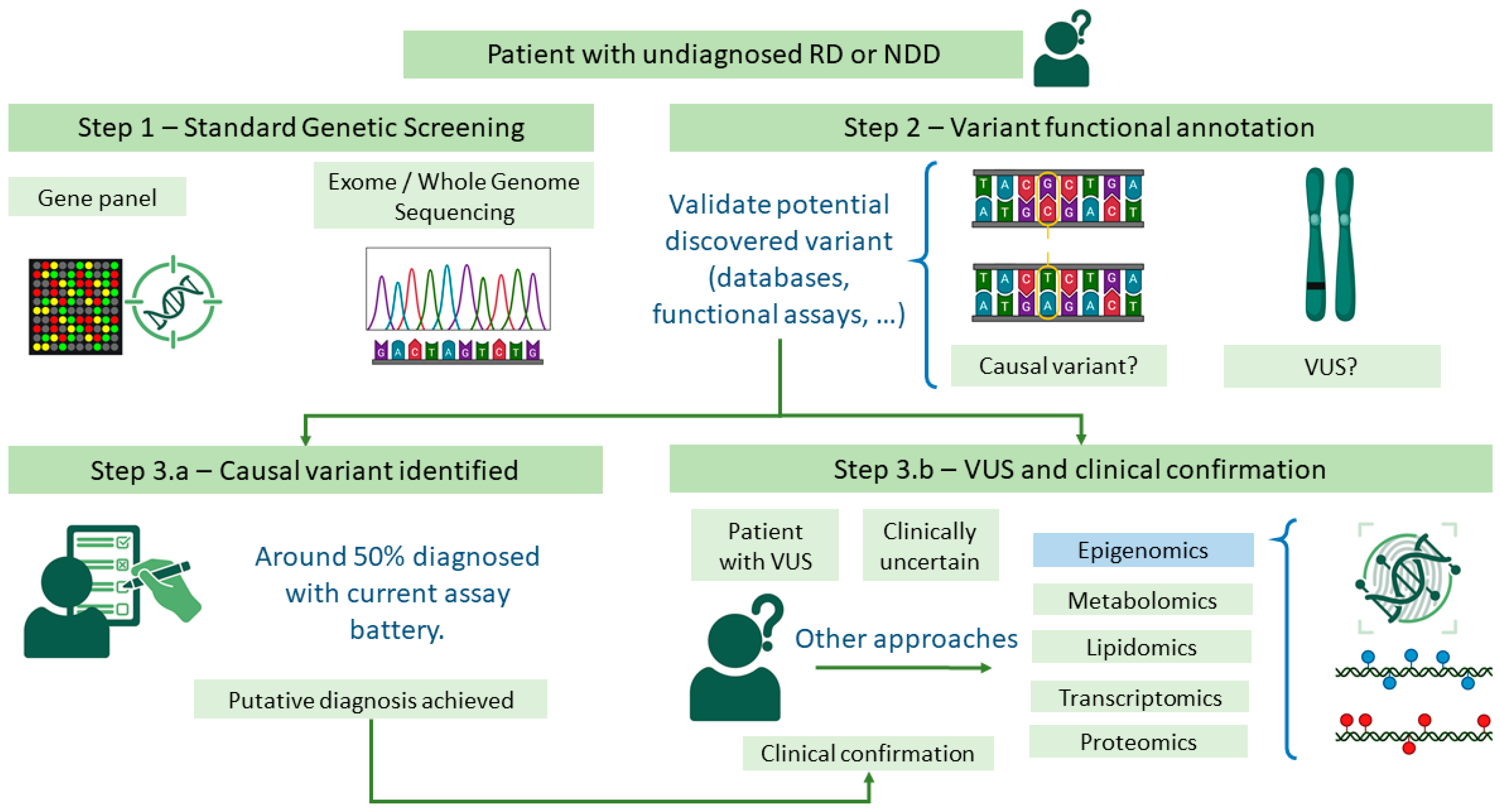

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Testing Episignatures

3.1.1. Testing Episignatures: External Resources

3.1.2. Testing Episignatures: Public Episignatures

3.2. Episignature Development

3.2.1. Episignature Development: Data Formats

3.2.2. Episignature Development: DNA Methylation Array Processing

3.2.3. Episignature Development: Multi-Cohort Studies

3.2.4. Episignature Development: Methylation Screening Using Sequencing Methods

3.2.5. Episignature Development: Differentially Methylated Position (DMP) Detection

3.2.6. Episignature Development: Other Approaches to Linear Models for Episignatures

3.2.7. Episignature Development: DMRs and Epimutations

3.2.8. Episignature Development: Annotation and Enrichment

3.2.9. Episignature Development: Classification Model Introduction

3.2.10. Episignature Development: Classification Model Pre-Filtering

3.2.11. Episignature Development: Classification Model Design

| Metric | Definition | Estimation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recall or sensitivity | Proportion of real positives correctly identified. | (TPs)/(TPs + FNs) | [206] |

| Specificity | Proportion of real negatives correctly identified. | (TNs)/(TNs + FPs) | [206] |

| Accuracy | Proportion of correctly classified instances. | (TPs + TNs)/(TPs + TNs + FPs + FNs) | [206] |

| Precision | Proportion of predicted positives that are actually positive. | (TPs)/(TPs + FPs) | [206] |

| AUC | Area under the ROC curve; represents trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. | Computed from ROC curve | [207] |

| F1 score | Harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity. | (2 × precision × sensitivity)/(precision + sensitivity) | [206] |

| Deviance | Comparison between trained model and perfect model. | −2 log L | [208] |

| Cohen’s kappa | Comparison between model predictions (Pr(a)) and random guessing (Pr(e)). | (Pr(a) − Pr(e))/(1 − Pr(e)) | [209] |

4. Discussion

- Sequencing via genome bisulfite sequencing or third-generation “five-base” callers. The latter offers promising results, since third-generation sequencing technologies could offer the detection of all available genetic variability, from intronic/exonic variants to whole- genome methylation [190].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CV | cross-validation |

| DMP | differentially methylated position |

| DMR | differentially methylated region |

| EGA | European Genome-Phenome Archive |

| eWASs | epigenome-wide association studies |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| MAF | minor allele frequency |

| ML | machine learning |

| NDD | neurodevelopmental disorder |

| RD | rare disease |

| RF | random forest |

| PLR | penalized logistic regression |

| QC | quality control |

| SNVs | single-nucleotide variants |

| SVM | support vector machine |

| VUS | variants of uncertain significance |

| WES | whole-exome sequencing |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing |

References

- The Lancet Global Health. The Landscape for Rare Diseases in 2024. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e341. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikova, I. Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 267–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haendel, M.; Vasilevsky, N.; Unni, D.; Bologa, C.; Harris, N.; Rehm, H.; Hamosh, A.; Baynam, G.; Groza, T.; McMurry, J.; et al. How Many Rare Diseases Are There? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguengang Wakap, S.; Lambert, D.M.; Olry, A.; Rodwell, C.; Gueydan, C.; Lanneau, V.; Murphy, D.; Le Cam, Y.; Rath, A. Estimating Cumulative Point Prevalence of Rare Diseases: Analysis of the Orphanet Database. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, J.; Zimmer-Bensch, G. The Epigenome in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 776809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodosevich, K.; Sellgren, C.M. Neurodevelopmental Disorders—High-Resolution Rethinking of Disease Modeling. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 28, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels-Igbokwe, C.; McInnes, B.; MacDonald, K.V.; Currie, G.R.; Omar, F.; Shewchuk, B.; Bernier, F.P.; Marshall, D.A. (Un)Standardized Testing: The Diagnostic Odyssey of Children with Rare Genetic Disorders in Alberta, Canada. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenon, J.; Duffourd, Y.; Masurel-Paulet, A.; Lefebvre, M.; Feillet, F.; El Chehadeh-Djebbar, S.; St-Onge, J.; Steinmetz, A.; Huet, F.; Chouchane, M.; et al. Diagnostic Odyssey in Severe Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Toward Clinical Whole-Exome Sequencing as a First-Line Diagnostic Test. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sanden, B.P.G.H.; Schobers, G.; Corominas Galbany, J.; Koolen, D.A.; Sinnema, M.; van Reeuwijk, J.; Stumpel, C.T.R.M.; Kleefstra, T.; de Vries, B.B.A.; Ruiterkamp-Versteeg, M.; et al. The Performance of Genome Sequencing as a First-Tier Test for Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 31, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, T.; Lemire, G.; Kernohan, K.D.; Howley, H.E.; Adams, D.R.; Boycott, K.M. New Diagnostic Approaches for Undiagnosed Rare Genetic Diseases. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2020, 21, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, S.; Knowles, J.W.; Ashley, E.A. A Guide for the Diagnosis of Rare and Undiagnosed Disease: Beyond the Exome. Genome Med. 2022, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, K.; Sadikovic, B. DNA Methylation Episignatures in Neurodevelopmental Disorders Associated with Large Structural Copy Number Variants: Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joynt, A.C.M.; Axford, M.M.; Chad, L.; Costain, G. Understanding Genetic Variants of Uncertain Significance. Paediatr. Child. Health 2021, 27, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, A.; Mangaonkar, A.A.; Stroik, S.; Zimmermann, M.T.; Sigafoos, A.N.; Kamath, P.S.; Simonetto, D.A.; Wylam, M.E.; Carmona, E.M.; Lazaridis, K.N.; et al. Functional Validation of TERT and TERC Variants of Uncertain Significance in Patients with Short Telomere Syndromes. Blood Cancer J. 2020, 10, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.P. Epigenetics: Principles and Practice. Dig. Dis. 2011, 29, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinel, C.; Prainsack, B.; McKevitt, C. Markers as Mediators: A Review and Synthesis of Epigenetics Literature. BioSocieties 2017, 13, 276–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.P.; Merrill, S.M.; Sharma, M.; Gibson, W.T.; Turvey, S.E.; Kobor, M.S. Rare Diseases of Epigenetic Origin: Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1113086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornsson, H.T. The Mendelian Disorders of the Epigenetic Machinery. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1473–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, P. Uniparental Disomy: Origin, Frequency, and Clinical Significance. Prenat. Diagn. 2021, 41, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, J.; Rastin, C.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; McConkey, H.; Demain, L.; Dominguez-Garrido, E.; Kaat, L.D.; Houge, S.D.; DuPont, B.R.; et al. Diagnostic Utility and Reporting Recommendations for Clinical DNA Methylation Episignature Testing in Genetically Undiagnosed Rare Diseases. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, L.; Huang, Y.; Ohno-Machado, L. Privacy Challenges and Research Opportunities for Genomic Data Sharing. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittos, A.; Malin, B.; De Cristofaro, E. Systematizing Genome Privacy Research: A Privacy-Enhancing Technologies Perspective. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2017, 2019, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chater-Diehl, E.; Goodman, S.J.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Turinsky, A.L.; Choufani, S.; Weksberg, R. Anatomy of DNA Methylation Signatures: Emerging Insights and Applications. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turinsky, A.L.; Choufani, S.; Lu, K.; Liu, D.; Mashouri, P.; Min, D.; Weksberg, R.; Brudno, M. EpigenCentral: Portal for DNA Methylation Data Analysis and Classification in Rare Diseases. Hum. Mutat. 2020, 41, 1722–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Kerkhof, J.; Pedro, V.P.; Barat-Houari, M.; Ruiz-Pallares, N.; Andrau, J.C.; Lacombe, D.; Van-Gils, J.; Fergelot, P.; Dubourg, C.; et al. Evaluation of DNA Methylation Episignatures for Diagnosis and Phenotype Correlations in 42 Mendelian Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 106, 356–370, Erratum in Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1161–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, S.; Bhai, P.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Sadikovic, B. Diagnostic Utility of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis in Mendelian Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davide, G.; Rebecca, C.; Irene, P.; Luciano, C.; Francesco, R.; Marta, N.; Miriam, O.; Natascia, B.; Pierluigi, P. Epigenetics of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Multi-Level Analysis Combining Epi-Signature, Age Acceleration, Epigenetic Drift and Rare Epivariations Using Public Datasets. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 2362–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, S.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; McConkey, H.; Balci, T.; Siu, V.M.; Skinner, C.D.; Stevenson, R.E.; Sadikovic, B.; et al. Detection of a Dna Methylation Signature for the Intellectual Developmental Disorder, x-Linked, Syndromic, Armfield Type. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchi, C.; Oussalah, A.; Falliano, S.; Ferri, L.; Gozzini, A.; Gasperini, S.; Motta, S.; Rigoldi, M.; Parenti, G.; Tummolo, A.; et al. PRDX1 Gene-Related Epi-CblC Disease Is a Common Type of Inborn Error of Cobalamin Metabolism with Mono- or Bi-Allelic MMACHC Epimutations. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Jadhav, B.; Rodriguez, O.L.; Patel, N.; Martin-Trujillo, A.; Jain, M.; Metsu, S.; Olsen, H.; Paten, B.; Ritz, B.; et al. A Survey of Rare Epigenetic Variation in 23,116 Human Genomes Identifies Disease-Relevant Epivariations and CGG Expansions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 107, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prickett, A.R.; Ishida, M.; Böhm, S.; Frost, J.M.; Puszyk, W.; Abu-Amero, S.; Stanier, P.; Schulz, R.; Moore, G.E.; Oakey, R.J. Genome-Wide Methylation Analysis in Silver–Russell Syndrome Patients. Hum. Genet. 2015, 134, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, R.; Nakata, M.; Funabiki, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Awaya, T.; Murai, T.; Hagiwara, M. An Epigenetic Biomarker for Adult High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, F.; Drost, M.; van der Linde, H.; Bardina, L.; Smits, D.; de Graaf, B.M.; Schot, R.; van Bever, Y.; Brooks, A.; Kaat, L.D.; et al. Training with Synthetic Data Provides Accurate and Openly-Available DNA Methylation Classifiers for Developmental Disorders and Congenital Anomalies via MethaDory. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radio, F.C.; Pang, K.; Ciolfi, A.; Levy, M.A.; Hernández-García, A.; Pedace, L.; Pantaleoni, F.; Liu, Z.; de Boer, E.; Jackson, A.; et al. SPEN Haploinsufficiency Causes a Neurodevelopmental Disorder Overlapping Proximal 1p36 Deletion Syndrome with an Episignature of X Chromosomes in Females. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Bend, E.G.; Colaiacovo, S.; Caudle, M.; Chakrabarti, R.; Napier, M.; Brick, L.; Brady, L.; Carere, D.A.; Levy, M.A.; et al. Diagnostic Utility of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Testing in Genetically Unsolved Individuals with Suspected Hereditary Conditions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, E.; Butcher, D.T.; Singhania, R.; Mervis, C.B.; Morris, C.A.; De Carvalho, D.; Weksberg, R.; Osborne, L.R. Symmetrical Dose-Dependent DNA-Methylation Profiles in Children with Deletion or Duplication of 7q11.23. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 97, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; McConkey, H.; Pranckeviciene, E.; Kerkhof, J.; Barat-Houari, M.; Bargiacchi, S.; Biamino, E.; Palomares Bralo, M.; Cappuccio, G.; et al. Functional Correlation of Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiles in Genetic Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Hum. Mutat. 2022, 43, 1609–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rots, D.; Rooney, K.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Pfundt, R.; Marcelis, C.; Willemsen, M.H.; van Hagen, J.M.; Zwijnenburg, P.; et al. Refining the 9q34.3 Microduplication Syndrome Reveals Mild Neurodevelopmental Features Associated with a Distinct Global DNA Methylation Profile. Clin. Genet. 2024, 105, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.A.; McConkey, H.; Kerkhof, J.; Barat-Houari, M.; Bargiacchi, S.; Biamino, E.; Bralo, M.P.; Cappuccio, G.; Ciolfi, A.; Clarke, A.; et al. Novel Diagnostic DNA Methylation Episignatures Expand and Refine the Epigenetic Landscapes of Mendelian Disorders. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2022, 3, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, K.; Levy, M.A.; Haghshenas, S.; Kerkhof, J.; Rogaia, D.; Tedesco, M.G.; Imperatore, V.; Mencarelli, A.; Squeo, G.M.; Di Venere, E.; et al. Identification of a Dna Methylation Episignature in the 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmel, M.; Michaelovsky, E.; Weinberger, R.; Frisch, A.; Mekori-Domachevsky, E.; Gothelf, D.; Weizman, A. Differential Methylation of Imprinting Genes and MHC Locus in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome-Related Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 22, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garau, J.; Charras, A.; Varesio, C.; Orcesi, S.; Dragoni, F.; Galli, J.; Fazzi, E.; Gagliardi, S.; Pansarasa, O.; Cereda, C.; et al. Altered DNA Methylation and Gene Expression Predict Disease Severity in Patients with Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 249, 109299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkel, L.C.; Kernohan, K.D.; McBride, A.; Reina, D.; Hodge, A.; Ainsworth, P.J.; Rodenhiser, D.I.; Pare, G.; Bérubé, N.G.; Skinner, C.; et al. Identification of Epigenetic Signature Associated with Alpha Thalassemia/Mental Retardation X-Linked Syndrome. Epigenetics Chromatin 2017, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Rodenhiser, D.I.; Schenkel, L.C.; Lin, H.; Skinner, C.; Ainsworth, P.; Paré, G.; Hood, R.L.; Bulman, D.E.; Kernohan, K.D.; et al. Genomic DNA Methylation Signatures Enable Concurrent Diagnosis and Clinical Genetic Variant Classification in Neurodevelopmental Syndromes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 102, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdayer, C.; Rooney, K.; van der Laan, L.; Bris, C.; Alders, M.; Bahr, A.; Barcia, G.; Battault, C.; Begemann, A.; Bonneau, D.; et al. ARID2-Related Disorder: Further Delineation of the Clinical Phenotype of 27 Novel Individuals and Description of an Epigenetic Signature. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 10, 1422–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, G.F.d.S.; Costa, T.V.M.M.; Nascimento, A.M.; Wolff, B.M.; Damasceno, J.G.; Vieira, L.L.; Almeida, V.T.; de Oliveira, Y.G.; de Mello, C.B.; Muszkat, M.; et al. DNA Methylation Epi-Signature and Biological Age in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2023, 228, 107714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choufani, S.; McNiven, V.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Jangjoo, M.; Adam, M.P.; Bjornsson, H.T.; Harris, J.; Dyment, D.A.; Graham, G.E.; Nezarati, M.M.; et al. An HNRNPK-Specific DNA Methylation Signature Makes Sense of Missense Variants and Expands the Phenotypic Spectrum of Au-Kline Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 109, 1867–1884, Erratum in Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, M.T.; Butcher, D.T.; Turinsky, A.L.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Stavropoulos, D.J.; Walker, S.; Caluseriu, O.; Carter, M.; Lou, Y.; Nicolson, R.; et al. Functional DNA Methylation Signatures for Autism Spectrum Disorder Genomic Risk Loci: 16p11.2 Deletions and CHD8 Variants. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P.; Sharp, A.J. Screening for Rare Epigenetic Variations in Autism and Schizophrenia. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sluijs, P.J.; Moutton, S.; Dingemans, A.J.M.; Weis, D.; Levy, M.A.; Boycott, K.M.; Arberas, C.; Baldassarri, M.; Beneteau, C.; Brusco, A.; et al. Microduplications of ARID1A and ARID1B Cause a Novel Clinical and Epigenetic Distinct BAFopathy. Genet. Med. 2025, 27, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qannan, A.; Bejaoui, Y.; Izadi, M.; Yousri, N.A.; Razzaq, A.; Christiansen, C.; Martin, G.M.; Bell, J.T.; Horvath, S.; Oshima, J.; et al. Accelerated Epigenetic Aging and DNA Methylation Alterations in Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbagh, Q.; Haghshenas, S.; Piard, J.; Trouvé, C.; Amiel, J.; Attié-Bitach, T.; Balci, T.; Barat-Houari, M.; Belonis, A.; Boute, O.; et al. Clinico-Biological Refinement of BCL11B-Related Disorder and Identification of an Episignature: A Series of 20 Unreported Individuals. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.A.; Beck, D.B.; Metcalfe, K.; Douzgou, S.; Sithambaram, S.; Cottrell, T.; Ansar, M.; Kerkhof, J.; Mignot, C.; Nougues, M.C.; et al. Deficiency of TET3 Leads to a Genome-Wide DNA Hypermethylation Episignature in Human Whole Blood. NPJ Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 92, Erratum in NPJ Genom. Med. 2021, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuccio, G.; Sayou, C.; Tanno, P.L.; Tisserant, E.; Bruel, A.L.; Kennani, S.E.; Sá, J.; Low, K.J.; Dias, C.; Havlovicová, M.; et al. De Novo SMARCA2 Variants Clustered Outside the Helicase Domain Cause a New Recognizable Syndrome with Intellectual Disability and Blepharophimosis Distinct from Nicolaides–Baraitser Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 1838–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarli, C.; van der Laan, L.; Reilly, J.; Trajkova, S.; Carli, D.; Brusco, A.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; et al. Blepharophimosis with Intellectual Disability and Helsmoortel-Van Der Aa Syndrome Share Episignature and Phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2024, 196, e32089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awamleh, Z.; Chater-Diehl, E.; Choufani, S.; Wei, E.; Kianmahd, R.R.; Yu, A.; Chad, L.; Costain, G.; Tan, W.H.; Scherer, S.W.; et al. DNA Methylation Signature Associated with Bohring-Opitz Syndrome: A New Tool for Functional Classification of Variants in ASXL Genes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouxel, F.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Levy, M.; Dias, P.; Barat-Houari, M.; Bednarek, N.; Boute, O.; Chatron, N.; et al. CDK13-Related Disorder: Report of a Series of 18 Previously Unpublished Individuals and Description of an Epigenetic Signature. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernohan, K.D.; Cigana Schenkel, L.; Huang, L.; Smith, A.; Pare, G.; Ainsworth, P.; Care4Rare Canada Consortium; Boycott, K.M.; Warman-Chardon, J.; Sadikovic, B. Identification of a Methylation Profile for DNMT1-Associated Autosomal Dominant Cerebellar Ataxia, Deafness, and Narcolepsy. Clin. Epigenet. 2016, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peymani, F.; Ebihara, T.; Smirnov, D.; Kopajtich, R.; Ando, M.; Bertini, E.; Carrozzo, R.; Diodato, D.; Distelmaier, F.; Fang, F.; et al. Pleiotropic Effects of MORC2 Derive from Its Epigenetic Signature. Brain 2025, 9, awaf159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, D.T.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Turinsky, A.L.; Siu, M.T.; Inbar-Feigenberg, M.; Mendoza-Londono, R.; Chitayat, D.; Walker, S.; Machado, J.; Caluseriu, O.; et al. CHARGE and Kabuki Syndromes: Gene-Specific DNA Methylation Signatures Identify Epigenetic Mechanisms Linking These Clinically Overlapping Conditions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, N.; Haghshenas, S.; van der Laan, L.; Russel, P.K.M.; Rooney, K.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Maas, S.M.; et al. The Detection of a Strong Episignature for Chung–Jansen Syndrome, Partially Overlapping with Börjeson–Forssman–Lehmann and White–Kernohan Syndromes. Hum. Genet. 2024, 143, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkel, L.C.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Skinner, C.; Ainsworth, P.; Lin, H.; Paré, G.; Rodenhiser, D.I.; Schwartz, C.; Sadikovic, B. Peripheral Blood Epi-Signature of Claes-Jensen Syndrome Enables Sensitive and Specific Identification of Patients and Healthy Carriers with Pathogenic Mutations in KDM5C. Clin. Epigenet. 2018, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L.; Rooney, K.; Alders, M.; Relator, R.; McConkey, H.; Kerkhof, J.; Levy, M.A.; Lauffer, P.; Aerden, M.; Theunis, M.; et al. Episignature Mapping of TRIP12 Provides Functional Insight into Clark-Baraitser Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Bend, E.G.; Hood, R.L.; Schenkel, L.C.; Carere, D.A.; Chakrabarti, R.; Nagamani, S.C.S.; Cheung, S.W.; Campeau, P.M.; Prasad, C.; et al. BAFopathies’ DNA Methylation Epi-Signatures Demonstrate Diagnostic Utility and Functional Continuum of Coffin–Siris and Nicolaides–Baraitser Syndromes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jawahiri, R.; Foroutan, A.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Levy, M.; Haghshenas, S.; Rooney, K.; Turner, J.; Shears, D.; Holder, M.; et al. SOX11 Variants Cause a Neurodevelopmental Disorder with Infrequent Ocular Malformations and Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism and with Distinct DNA Methylation Profile. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFlamme, C.W.; Rastin, C.; Sengupta, S.; Pennington, H.E.; Russ-Hall, S.J.; Schneider, A.L.; Bonkowski, E.S.; Almanza Fuerte, E.P.; Allan, T.J.; Zalusky, M.P.G.; et al. Diagnostic Utility of DNA Methylation Analysis in Genetically Unsolved Pediatric Epilepsies and CHD2 Episignature Refinement. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, K.; van der Laan, L.; Trajkova, S.; Haghshenas, S.; Relator, R.; Lauffer, P.; Vos, N.; Levy, M.A.; Brunetti-Pierri, N.; Terrone, G.; et al. DNA Methylation Episignature and Comparative Epigenomic Profiling of HNRNPU-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K.; Weis, D.; Aukrust, I.; Hsieh, T.C.; Horackova, M.; Paulsen, J.; Mendoza Londono, R.; Dupuis, L.; Dickson, M.; Lesman, H.; et al. Epigenomic and Phenotypic Characterization of DEGCAGS Syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 1574–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nil, Z.; Deshwar, A.R.; Huang, Y.; Barish, S.; Zhang, X.; Choufani, S.; Le Quesne Stabej, P.; Hayes, I.; Yap, P.; Haldeman-Englert, C.; et al. Rare de Novo Gain-of-Function Missense Variants in DOT1L Are Associated with Developmental Delay and Congenital Anomalies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacalini, M.G.; Gentilini, D.; Boattini, A.; Giampieri, E.; Pirazzini, C.; Giuliani, C.; Fontanesi, E.; Scurti, M.; Remondini, D.; Capri, M.; et al. Identification of a DNA Methylation Signature in Blood Cells from Persons with Down Syndrome. Aging 2015, 7, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreyer, L.; Reilly, J.; McConkey, H.; Kerkhof, J.; Levy, M.A.; Hu, J.; Hnaini, M.; Sadikovic, B.; Campbell, C. The Discovery of the DNA Methylation Episignature for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2023, 33, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courraud, J.; Chater-Diehl, E.; Durand, B.; Vincent, M.; del Mar Muniz Moreno, M.; Boujelbene, I.; Drouot, N.; Genschik, L.; Schaefer, E.; Nizon, M.; et al. Integrative Approach to Interpret DYRK1A Variants, Leading to a Frequent Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciolfi, A.; Foroutan, A.; Capuano, A.; Pedace, L.; Travaglini, L.; Pizzi, S.; Andreani, M.; Miele, E.; Invernizzi, F.; Reale, C.; et al. Childhood-Onset Dystonia-Causing KMT2B Variants Result in a Distinctive Genomic Hypermethylation Profile. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oexle, K.; Zech, M.; Stühn, L.G.; Siegert, S.; Brunet, T.; Schmidt, W.M.; Wagner, M.; Schmidt, A.; Engels, H.; Tilch, E.; et al. Episignature Analysis of Moderate Effects and Mosaics. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ochoa, E.; Barwick, K.; Cif, L.; Rodger, F.; Docquier, F.; Pérez-Dueñas, B.; Clark, G.; Martin, E.; Banka, S.; et al. Comparison of Methylation Episignatures in KMT2B- and KMT2D-Related Human Disorders. Epigenomics 2022, 14, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza-Schreiber, N.; Zech, M.; Wilson, R.; Brunet, T.; Wagner, M.; Jech, R.; Boesch, S.; Škorvánek, M.; Necpál, J.; Weise, D.; et al. Blood DNA Methylation Provides an Accurate Biomarker of KMT2B-Related Dystonia and Predicts Onset. Brain 2022, 145, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussalah, A.; Siblini, Y.; Hergalant, S.; Chéry, C.; Rouyer, P.; Cavicchi, C.; Guerrini, R.; Morange, P.E.; Trégouët, D.; Pupavac, M.; et al. Epimutations in Both the TESK2 and MMACHC Promoters in the Epi-CblC Inherited Disorder of Intracellular Metabolism of Vitamin B12. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, D.; Ciolfi, A.; Pedace, L.; Haghshenas, S.; Ferilli, M.; Levy, M.A.; Miele, E.; Nardini, C.; Cappelletti, C.; Relator, R.; et al. Identification of a Robust DNA Methylation Signature for Fanconi Anemia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobben, J.M.; Krzyzewska, I.M.; Venema, A.; Mul, A.N.; Polstra, A.; Postma, A.V.; Smigiel, R.; Pesz, K.; Niklinski, J.; Chomczyk, M.A.; et al. DNA Methylation Abundantly Associates with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and Its Subphenotypes. Epigenomics 2019, 11, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzewska, I.M.; Lauffer, P.; Mul, A.N.; van der Laan, L.; Yim, A.Y.F.L.; Cobben, J.M.; Niklinski, J.; Chomczyk, M.A.; Smigiel, R.; Mannens, M.M.A.M.; et al. Expression Quantitative Trait Methylation Analysis Identifies Whole Blood Molecular Footprint in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, L.; Relator, R.; Valenzuela, I.; Mul, A.N.; Alders, M.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; Rzasa, J.; Cueto-González, A.M.; Lasa-Aranzasti, A.; et al. Discovery of a DNA Methylation Episignature as a Molecular Biomarker for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2025, 27, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghshenas, S.; Putoux, A.; Reilly, J.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; Ghosh, S.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Edery, P.; Lesca, G.; et al. Discovery of DNA Methylation Signature in the Peripheral Blood of Individuals with History of Antenatal Exposure to Valproic Acid. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, R.L.; Schenkel, L.C.; Nikkel, S.M.; Ainsworth, P.J.; Pare, G.; Boycott, K.M.; Bulman, D.E.; Sadikovic, B. The Defining DNA Methylation Signature of Floating-Harbor Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rots, D.; Chater-Diehl, E.; Dingemans, A.J.M.; Goodman, S.J.; Siu, M.T.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Choufani, S.; Hoang, N.; Walker, S.; Awamleh, Z.; et al. Truncating SRCAP Variants Outside the Floating-Harbor Syndrome Locus Cause a Distinct Neurodevelopmental Disorder with a Specific DNA Methylation Signature. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, L.C.; Schwartz, C.; Skinner, C.; Rodenhiser, D.I.; Ainsworth, P.J.; Pare, G.; Sadikovic, B. Clinical Validation of Fragile X Syndrome Screening by DNA Methylation Array. J. Mol. Diagn. 2016, 18, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.A.; Sears, R.L.; Gao, F.; Klein, E.D.; Karydas, A.; Geschwind, M.D.; Rosen, H.J.; Boxer, A.L.; Guo, W.; et al. An Epigenetic Signature in Peripheral Blood Associated with the Haplotype on 17q21.31, a Risk Factor for Neurodegenerative Tauopathy. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherik, F.; Reilly, J.; Kerkhof, J.; Levy, M.; McConkey, H.; Barat-Houari, M.; Butler, K.M.; Coubes, C.; Lee, J.A.; Le Guyader, G.; et al. DNA Methylation Episignature in Gabriele-de Vries Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2022, 24, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L.; Karimi, K.; Rooney, K.; Lauffer, P.; McConkey, H.; Caro, P.; Relator, R.; Levy, M.A.; Bhai, P.; Mignot, C.; et al. DNA Methylation Episignature, Extension of the Clinical Features, and Comparative Epigenomic Profiling of Hao-Fountain Syndrome Caused by Variants in USP7. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.S.; Garg, P.; Tang, L.; Mendonca, D.; Levy, T.; Barbosa, M.; Arnett, A.B.; Kurtz-Nelson, E.; Agolini, E.; Battaglia, A.; et al. Episignatures Stratifying Helsmoortel-Van Der Aa Syndrome Show Modest Correlation with Phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 107, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bend, E.G.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Everman, D.B.; Rogers, R.C.; Cathey, S.S.; Prijoles, E.J.; Lyons, M.J.; Davis, H.; Clarkson, K.; Gripp, K.W.; et al. Gene Domain-Specific DNA Methylation Episignatures Highlight Distinct Molecular Entities of ADNP Syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Ochoa, E.; Badura-Stronka, M.; Donnelly, D.; Lederer, D.; Lynch, S.A.; Gardham, A.; Morton, J.; Stewart, H.; Docquier, F.; et al. Germline Pathogenic Variants in HNRNPU Are Associated with Alterations in Blood Methylome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, G.; Grillo, G.; Touleimat, N.; Ferry, L.; Ivkovic, I.; Ribierre, F.; Deleuze, J.F.; Chantalat, S.; Picard, C.; Francastel, C. Comparative Methylome Analysis of ICF Patients Identifies Heterochromatin Loci That Require ZBTB24, CDCA7 and HELLS for Their Methylated State. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2409–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, G.; Ulveling, D.; Rondeau, S.; Marzin, P.; Unoki, M.; Cormier-Daire, V.; Francastel, C. Interplay between Histone and Dna Methylation Seen through Comparative Methylomes in Rare Mendelian Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, K.; Mol, M.O.; Haghshenas, S.; Relator, R.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Brooks, A.; Zonneveld-Huijssoon, E.; Gerkes, E.H.; et al. Identification of DNA Methylation Episignature for the Intellectual Developmental Disorder, Autosomal Dominant 21 Syndrome, Caused by Variants in the CTCF Gene. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, E.A.; van der Laan, L.; Haghshenas, S.; Rooney, K.; Levy, M.A.; Alders, M.; Maas, S.M.; Jansen, S.; Lieden, A.; Anderlid, B.M.; et al. DNA Methylation Signature for JARID2-Neurodevelopmental Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L.; Rooney, K.; Haghshenas, S.; Silva, A.; McConkey, H.; Relator, R.; Levy, M.A.; Valenzuela, I.; Trujillano, L.; Lasa-Aranzasti, A.; et al. Functional Insight into and Refinement of the Genomic Boundaries of the JARID2-Neurodevelopmental Disorder Episignature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagami, M.; Matsubara, K.; Nakabayashi, K.; Nakamura, A.; Sano, S.; Okamura, K.; Hata, K.; Fukami, M.; Ogata, T. Genome-Wide Multilocus Imprinting Disturbance Analysis in Temple Syndrome and Kagami-Ogata Syndrome. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Schenkel, L.C.; Lin, H.; Skinner, C.; Ainsworth, P.; Paré, G.; Rodenhiser, D.; Schwartz, C.; Sadikovic, B. The Defining DNA Methylation Signature of Kabuki Syndrome Enables Functional Assessment of Genetic Variants of Unknown Clinical Significance. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobreira, N.; Brucato, M.; Zhang, L.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Ongaco, C.; Romm, J.; Doheny, K.F.; Mingroni-Netto, R.C.; Bertola, D.; Kim, C.A.; et al. Patients with a Kabuki Syndrome Phenotype Demonstrate DNA Methylation Abnormalities. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 25, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuili, E.; Grolaux, R.; Macedo, C.Z.N.M.; Desmyter, L.; Pichon, B.; Neuens, S.; Vilain, C.; Olsen, C.; Van Dooren, S.; Smits, G.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Implementation of Episignatures for Diagnosis of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs). Hum. Genet. 2023, 142, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awamleh, Z.; Choufani, S.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Alkuraya, F.S.; Scherer, S.; Fernandes, S.; Rosas, C.; Louro, P.; Dias, P.; Neves, M.T.; et al. ANKRD11 Pathogenic Variants and 16q24.3 Microdeletions Share an Altered DNA Methylation Signature in Patients with KBG Syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Jaarsveld, R.H.; Reilly, J.; Cornips, M.C.; Hadders, M.A.; Agolini, E.; Ahimaz, P.; Anyane-Yeboa, K.; Bellanger, S.A.; van Binsbergen, E.; van den Boogaard, M.J.; et al. Delineation of a KDM2B-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder and Its Associated DNA Methylation Signature. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, S.J.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Chung, B.H.Y.; Chater-Diehl, E.; Aziz, C.; Turinsky, A.L.; Kellam, B.; Keller, M.; Ko, J.M.; Caluseriu, O.; et al. EHMT1 Pathogenic Variants and 9q34.3 Microdeletions Share Altered DNA Methylation Patterns in Patients with Kleefstra Syndrome. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2020, 4, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rots, D.; Choufani, S.; Faundes, V.; Dingemans, A.J.M.; Joss, S.; Foulds, N.; Jones, E.A.; Stewart, S.; Vasudevan, P.; Dabir, T.; et al. Pathogenic Variants in KMT2C Result in a Neurodevelopmental Disorder Distinct from Kleefstra and Kabuki Syndromes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awamleh, Z.; Choufani, S.; Wu, W.; Rots, D.; Dingemans, A.J.M.; Nadif Kasri, N.; Boronat, S.; Ibañez-Mico, S.; Cuesta Herraiz, L.; Ferrer, I.; et al. A New Blood DNA Methylation Signature for Koolen-de Vries Syndrome: Classification of Missense KANSL1 Variants and Comparison to Fibroblast Cells. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 324–332, Erratum in Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Menzies, L.; Hay, E.; Ochoa, E.; Docquier, F.; Rodger, F.; Deshpande, C.; Foulds, N.C.; Jacquemont, S.; Jizi, K.; et al. Epigenotype-Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in SETD1A and SETD2 Chromatin Disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dámaso, E.; Castillejo, A.; Arias, M.d.M.; Canet-Hermida, J.; Navarro, M.; del Valle, J.; Campos, O.; Fernández, A.; Marín, F.; Turchetti, D.; et al. Primary Constitutional MLH1 Epimutations: A Focal Epigenetic Event. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, S.; Bout, H.J.; Schijns, J.M.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; Bhai, P.; McConkey, H.; Jenkins, Z.A.; Williams, E.M.; Halliday, B.J.; et al. Menke-Hennekam Syndrome; Delineation of Domain-Specific Subtypes with Distinct Clinical and DNA Methylation Profiles. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2024, 5, 100287, Erratum in Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2024, 5, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraffi, S.G.; van der Laan, L.; Rooney, K.; Trajkova, S.; Zuntini, R.; Relator, R.; Haghshenas, S.; Levy, M.A.; Baldo, C.; Mandrile, G.; et al. Identification of the DNA Methylation Signature of Mowat-Wilson Syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayol, R.; Borroto, M.C.; Haghshenas, S.; Namasivayam, A.; Reilly, J.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Shvedunova, M.; et al. MSL2 Variants Lead to a Neurodevelopmental Syndrome with Lack of Coordination, Epilepsy, Specific Dysmorphisms, and a Distinct Episignature. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 1330–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, L.; Silva, A.; Kleinendorst, L.; Rooney, K.; Haghshenas, S.; Lauffer, P.; Alanay, Y.; Bhai, P.; Brusco, A.; de Munnik, S.; et al. CUL3-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder: Clinical Phenotype of 20 New Individuals and Identification of a Potential Phenotype-Associated Episignature. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2025, 6, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chater-Diehl, E.; Ejaz, R.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Siu, M.T.; Turinsky, A.; Choufani, S.; Goodman, S.J.; Abdul-Rahman, O.; Bedford, M.; Dorrani, N.; et al. New Insights into DNA Methylation Signatures: SMARCA2 Variants in Nicolaides-Baraitser Syndrome. BMC Med. Genom. 2019, 12, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkel, L.C.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Rooney, K.; Kerkhof, J.; Levy, M.A.; McConkey, H.; Rogers, R.C.; Phelan, K.; Sarasua, S.M.; Jain, L.; et al. DNA Methylation Epi-Signature Is Associated with Two Molecularly and Phenotypically Distinct Clinical Subtypes of Phelan-McDermid Syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, L.; Lauffer, P.; Rooney, K.; Silva, A.; Haghshenas, S.; Relator, R.; Levy, M.A.; Trajkova, S.; Huisman, S.A.; Bijlsma, E.K.; et al. DNA Methylation Episignature and Comparative Epigenomic Profiling for Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome Caused by TCF4 Variants. Hum. Genet. Genom. Adv. 2024, 5, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Isono, K.; Matsubara, K.; Fuke, T.; Yamazawa, K.; Satou, K.; Murakami, N.; Saitoh, S.; Nakabayashi, K.; Hata, K.; Ogata, T.; et al. Genome-Wide Methylation Analysis in Silver–Russell Syndrome, Temple Syndrome, and Prader–Willi Syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, A.; Paccaud, J.; Orefice, M.; Colin, E.; Mäkitie, O.; Cormier-Daire, V.; Relator, R.; Ghosh, S.; Strub, J.-M.; Schaeffer-Reiss, C.; et al. PTBP1 Variants Displaying Altered Nucleocytoplasmic Distribution Are Responsible for a Neurodevelopmental Disorder with Skeletal Dysplasia. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 40, e182100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Dai, W.; Zhan, Y.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, D.P.; Xu, N.; Yu, Y. Genome-Wide Epigenetic Signatures Facilitated the Variant Classification of the PURA Gene and Uncovered the Pathomechanism of PURA-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Genet. Med. 2024, 26, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolfi, A.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Pizzi, S.; Pedace, L.; Miele, E.; Kerkhof, J.; Flex, E.; Martinelli, S.; Radio, F.C.; Ruivenkamp, C.A.L.; et al. Frameshift Mutations at the C-Terminus of HIST1H1E Result in a Specific DNA Hypomethylation Signature. Clin. Epigenet. 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, S.; Karimi, K.; Stevenson, R.E.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; Rzasa, J.; McConkey, H.; Lauzon-Young, C.; Balci, T.B.; et al. Identification of a DNA Methylation Episignature for Recurrent Constellations of Embryonic Malformations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 111, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, S.; Foroutan, A.; Bhai, P.; Levy, M.A.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Skinner, C.D.; Caylor, R.C.; Tedder, M.L.; et al. Identification of a DNA Methylation Signature for Renpenning Syndrome (RENS1), a Spliceopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava, C.; Cogne, B.; Santini, A.; Leitão, E.; Lecoquierre, F.; Chen, Y.; Stenton, S.L.; Besnard, T.; Heide, S.; Baer, S.; et al. Dominant Variants in Major Spliceosome U4 and U5 Small Nuclear RNA Genes Cause Neurodevelopmental Disorders through Splicing Disruption. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1374–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevilla-Porras, M.; Nieto-Molina, E.; Medina, Z.; Damián, A.; Tejedor, J.R.; Ruiz-Arenas, C.; Cazalla, M.; Carmona, R.; Amigo, J.; Goicoechea, I.; et al. Characterization of SnRNA-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorders through the Spanish Undiagnosed Rare Disease Programs. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzewska, I.M.; Maas, S.M.; Henneman, P.; Lip, K.V.D.; Venema, A.; Baranano, K.; Chassevent, A.; Aref-Eshghi, E.; Van Essen, A.J.; Fukuda, T.; et al. A Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Signature for SETD1B-Related Syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K.; Lichtenstein, Y.; Reilly, J.; McConkey, H.; Relator, R.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; Bouman, A.; Symonds, J.D.; Ghoumid, J.; et al. Discovery of a DNA Methylation Profile in Individuals with Sifrim-Hitz-Weiss Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2025, 112, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choufani, S.; Cytrynbaum, C.; Chung, B.H.Y.; Turinsky, A.L.; Grafodatskaya, D.; Chen, Y.A.; Cohen, A.S.A.; Dupuis, L.; Butcher, D.T.; Siu, M.T.; et al. NSD1 Mutations Generate a Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Signature. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, E.; Garde, A.; Gautier, T.; Rooney, K.; Duffourd, Y.; LeBlanc, P.; van Reempts, E.; Tran Mau-Them, F.; Wentzensen, I.M.; Au, K.S.; et al. SRSF1 Haploinsufficiency Is Responsible for a Syndromic Developmental Disorder Associated with Intellectual Disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffries, A.R.; Maroofian, R.; Salter, C.G.; Chioza, B.A.; Cross, H.E.; Patton, M.A.; Dempster, E.; Karen Temple, I.; Mackay, D.J.G.; Rezwan, F.I.; et al. Growth Disrupting Mutations in Epigenetic Regulatory Molecules Are Associated with Abnormalities of Epigenetic Aging. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.; Joshi, R.S.; Garg, P.; Martin-Trujillo, A.; Patel, N.; Jadhav, B.; Watson, C.T.; Gibson, W.; Chetnik, K.; Tessereau, C.; et al. Identification of Rare de Novo Epigenetic Variations in Congenital Disorders. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choufani, S.; Gibson, W.T.; Turinsky, A.L.; Chung, B.H.Y.; Wang, T.; Garg, K.; Vitriolo, A.; Cohen, A.S.A.; Cyrus, S.; Goodman, S.; et al. DNA Methylation Signature for EZH2 Functionally Classifies Sequence Variants in Three PRC2 Complex Genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 106, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastafierro, T.; Bacalini, M.G.; Marcoccia, A.; Gentilini, D.; Pisoni, S.; Di Blasio, A.M.; Corsi, A.; Franceschi, C.; Raimondo, D.; Spanò, A.; et al. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Analysis in Blood Cells from Patients with Werner Syndrome. Clin. Epigenet. 2017, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maierhofer, A.; Flunkert, J.; Oshima, J.; Martin, G.M.; Poot, M.; Nanda, I.; Dittrich, M.; Müller, T.; Haaf, T. Epigenetic Signatures of Werner Syndrome Occur Early in Life and Are Distinct from Normal Epigenetic Aging Processes. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foroutan, A.; Haghshenas, S.; Bhai, P.; Levy, M.A.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Niceta, M.; Ciolfi, A.; Pedace, L.; Miele, E.; et al. Clinical Utility of a Unique Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Signature for KMT2A-Related Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, R.; Lardenoije, R.; Tomiwa, K.; Funabiki, Y.; Nakata, M.; Suzuki, S.; Awaya, T.; Kato, T.; Okazaki, S.; Murai, T.; et al. Integrated DNA Methylation Analysis Reveals a Potential Role for ANKRD30B in Williams Syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen-van der Spek, J.; Relator, R.; Kerkhof, J.; McConkey, H.; Levy, M.A.; Tedder, M.L.; Louie, R.J.; Fletcher, R.S.; Moore, H.W.; Childers, A.; et al. DNA Methylation Episignature for Witteveen-Kolk Syndrome Due to SIN3A Haploinsufficiency. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Kinoshita, S.; Takayama, Y.; Ohnishi, E.; Kamura, H.; Kojima, K.; Kikuchi, H.; Terao, M.; Sugawara, T.; Migita, O.; et al. Loss of Function in NSD2 Causes DNA Methylation Signature Similar to That in Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome. Genet. Med. Open 2024, 2, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EpigenCentral. Available online: https://epigen.ccm.sickkids.ca/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Awamleh, Z.; Goodman, S.; Kallurkar, P.; Wu, W.; Lu, K.; Choufani, S.; Turinsky, A.L.; Weksberg, R. Generation of DNA Methylation Signatures and Classification of Variants in Rare Neurodevelopmental Disorders Using EpigenCentral. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Episign—Providing Answers from Beyond the Genome The First Clinically Validated Diagnostic Test Utilizing Peripheral Blood to Assess Whole Genome Methylation. Available online: https://episign.com/#our-technology (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Husson, T.; Lecoquierre, F.; Nicolas, G.; Richard, A.C.; Afenjar, A.; Audebert-Bellanger, S.; Badens, C.; Bilan, F.; Bizaoui, V.; Boland, A.; et al. Episignatures in Practice: Independent Evaluation of Published Episignatures for the Molecular Diagnostics of Ten Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 32, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafodatskaya, D.; Chung, B.H.; Butcher, D.T.; Turinsky, A.L.; Goodman, S.J.; Choufani, S.; Chen, Y.A.; Lou, Y.; Zhao, C.; Rajendram, R.; et al. Multilocus Loss of DNA Methylation in Individuals with Mutations in the Histone H3 Lysine 4 Demethylase KDM5C. BMC Med. Genom. 2013, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geysens, M.; Huremagic, B.; Souche, E.; Breckpot, J.; Devriendt, K.; Peeters, H.; Van Buggenhout, G.; Van Esch, H.; Van Den Bogaert, K.; Vermeesch, J.R. Clinical Evaluation of Long-Read Sequencing-Based Episignature Detection in Developmental Disorders. Genome Med. 2025, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildonen, M.; Ferilli, M.; Hjortshøj, T.D.; Dunø, M.; Risom, L.; Bak, M.; Ek, J.; Møller, R.S.; Ciolfi, A.; Tartaglia, M.; et al. DNA Methylation Signature Classification of Rare Disorders Using Publicly Available Methylation Data. Clin. Genet. 2023, 103, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niceta, M.; Ciolfi, A.; Ferilli, M.; Pedace, L.; Cappelletti, C.; Nardini, C.; Hildonen, M.; Chiriatti, L.; Miele, E.; Dentici, M.L.; et al. DNA Methylation Profiling in Kabuki Syndrome: Reclassification of Germline KMT2D VUS and Sensitivity in Validating Postzygotic Mosaicism. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrmohamadi, M.; Sepehri, M.H.; Nazer, N.; Norouzi, M.R. A Comparative Overview of Epigenomic Profiling Methods. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 714687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryee, M.J.; Jaffe, A.E.; Corrada-Bravo, H.; Ladd-Acosta, C.; Feinberg, A.P.; Hansen, K.D.; Irizarry, R.A. Minfi: A Flexible and Comprehensive Bioconductor Package for the Analysis of Infinium DNA Methylation Microarrays. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Morris, T.J.; Webster, A.P.; Yang, Z.; Beck, S.; Feber, A.; Teschendorff, A.E. ChAMP: Updated Methylation Analysis Pipeline for Illumina BeadChips. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3982–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.J.; Butcher, L.M.; Feber, A.; Teschendorff, A.E.; Chakravarthy, A.R.; Wojdacz, T.K.; Beck, S. ChAMP: 450k Chip Analysis Methylation Pipeline. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Kibbe, W.A.; Lin, S.M. Lumi: A Pipeline for Processing Illumina Microarray. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1547–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Triche, T.J.; Laird, P.W.; Shen, H. SeSAMe: Reducing Artifactual Detection of DNA Methylation by Infinium BeadChips in Genomic Deletions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.L.; Hemani, G.; Smith, G.D.; Relton, C.; Suderman, M. Meffil: Efficient Normalization and Analysis of Very Large DNA Methylation Datasets. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3983–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; Scherer, M.; Assenov, Y.; Lutsik, P.; Walter, J.; Lengauer, T.; Bock, C. RnBeads 2.0: Comprehensive Analysis of DNA Methylation Data. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assenov, Y.; Müller, F.; Lutsik, P.; Walter, J.; Lengauer, T.; Bock, C. Comprehensive Analysis of DNA Methylation Data with RnBeads. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 1138–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Yan, L.; Hu, Q.; Sucheston, L.E.; Higgins, M.J.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Johnson, C.S.; Smiraglia, D.J.; Liu, S. IMA: An R Package for High-Throughput Analysis of Illumina’s 450K Infinium Methylation Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.H.; Han, M.R. MethylCallR: A Comprehensive Analysis Framework for Illumina Methylation Beadchip. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Iterson, M.; Tobi, E.W.; Slieker, R.C.; Den Hollander, W.; Luijk, R.; Slagboom, P.E.; Heijmans, B.T. MethylAid: Visual and Interactive Quality Control of Large Illumina 450k Datasets. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3435–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidsley, R.; Wong, C.C.Y.; Volta, M.; Lunnon, K.; Mill, J.; Schalkwyk, L.C. A Data-Driven Approach to Preprocessing Illumina 450K Methylation Array Data. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leek, J.T.; Johnson, W.E.; Parker, H.S.; Jaffe, A.E.; Storey, J.D. The Sva Package for Removing Batch Effects and Other Unwanted Variation in High-Throughput Experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, G.K.; Ritchie, M.; Thorne, N.; Wettenhall, J.; Shi, W.; Hu, Y. Limma: Linear Models for Microarray and RNA-Seq Data User’s Guide; The Bioconductor Project: Parkville, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. Limma Powers Differential Expression Analyses for RNA-Sequencing and Microarray Studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, L.A.; Koestler, D.C.; Butler, R.A.; Hansen, H.M.; Wiencke, J.K.; Kelsey, K.T.; Christensen, B.C. An Optimized Library for Reference-Based Deconvolution of Whole-Blood Biospecimens Assayed Using the Illumina HumanMethylationEPIC BeadArray. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Breeze, C.E.; Zheng, S.C.; Beck, S. A Comparison of Reference-Based Algorithms for Correcting Cell-Type Heterogeneity in Epigenome-Wide Association Studies. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.J.; Buckley, M.J.; Statham, A.L.; Pidsley, R.; Samaras, K.; Lord, R.V.; Clark, S.J.; Molloy, P.L. De Novo Identification of Differentially Methylated Regions in the Human Genome. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.E.; Murakami, P.; Lee, H.; Leek, J.T.; Fallin, M.D.; Feinberg, A.P.; Irizarry, R.A. Bump Hunting to Identify Differentially Methylated Regions in Epigenetic Epidemiology Studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.S.; Schwartz, D.A.; Yang, I.V.; Kechris, K.J. Comb-p: Software for Combining, Analyzing, Grouping and Correcting Spatially Correlated P-Values. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jay, N.; Papillon-Cavanagh, S.; Olsen, C.; El-Hachem, N.; Bontempi, G.; Haibe-Kains, B. MRMRe: An R Package for Parallelized MRMR Ensemble Feature Selection. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2365–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelegi-Siso, D.; De Prado, P.; Ronkainen, J.; Bustamante, M.; Gonzalez, J.R. Methylclock: A Bioconductor Package to Estimate DNA Methylation Age. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1759–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, R.G.; Sartor, M.A. Annotatr: Genomic Regions in Context. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, N.C.; Bock, C. LOLA: Enrichment Analysis for Genomic Region Sets and Regulatory Elements in R and Bioconductor. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipson, B.; Maksimovic, J.; Oshlack, A. MissMethyl: An R Package for Analyzing Data from Illumina’s HumanMethylation450 Platform. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimovic, J.; Oshlack, A.; Phipson, B. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis for Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Data. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Kuan, P.F. MethylGSA: A Bioconductor Package and Shiny App for DNA Methylation Data Length Bias Adjustment in Gene Set Testing. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1958–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatzoglou, A.; Hornik, K.; Smola, A.; Zeileis, A. Kernlab—An S4 Package for Kernel Methods in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2004, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgey, M.; Dali, R.; Eveleigh, R.; Chen, K.C.; Letourneau, L.; Fillon, J.; Michaud, M.; Caron, M.; Sandoval, J.; Lefebvre, F.; et al. GenPipes: An Open-Source Framework for Distributed and Scalable Genomic Analyses. Gigascience 2019, 8, giz037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triche, T.J.; Weisenberger, D.J.; Van Den Berg, D.; Laird, P.W.; Siegmund, K.D. Low-Level Processing of Illumina Infinium DNA Methylation BeadArrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Taylor, J.A. Reliability of DNA Methylation Measures Using Illumina Methylation BeadChip. Epigenetics 2021, 16, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimovic, J.; Gordon, L.; Oshlack, A. SWAN: Subset-Quantile within Array Normalization for Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touleimat, N.; Tost, J. Complete Pipeline for Infinium® Human Methylation 450K BeadChip Data Processing Using Subset Quantile Normalization for Accurate DNA Methylation Estimation. Epigenomics 2012, 4, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, J.P.; Labbe, A.; Lemire, M.; Zanke, B.W.; Hudson, T.J.; Fertig, E.J.; Greenwood, C.M.T.; Hansen, K.D. Functional Normalization of 450k Methylation Array Data Improves Replication in Large Cancer Studies. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Marabita, F.; Lechner, M.; Bartlett, T.; Tegner, J.; Gomez-Cabrero, D.; Beck, S. A Beta-Mixture Quantile Normalization Method for Correcting Probe Design Bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA Methylation Data. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, H.; Batalha, C.M.P.F.; Li, W.; Mpye, K.L.; Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Naslavsky, M.S.; Parra, E.J. A Systematic Evaluation of Normalization Methods and Probe Replicability Using Infinium EPIC Methylation Data. Clin. Epigenet. 2023, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Zhang, X.; Huang, C.C.; Jafari, N.; Kibbe, W.A.; Hou, L.; Lin, S.M. Comparison of Beta-Value and M-Value Methods for Quantifying Methylation Levels by Microarray Analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansell, G.; Gorrie-Stone, T.J.; Bao, Y.; Kumari, M.; Schalkwyk, L.S.; Mill, J.; Hannon, E. Guidance for DNA Methylation Studies: Statistical Insights from the Illumina EPIC Array. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Behnam, E.; Huang, J.; Moffatt, M.F.; Schaid, D.J.; Liang, L.; Lin, X. Fast and Robust Adjustment of Cell Mixtures in Epigenome-Wide Association Studies with SmartSVA. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babraham Bioinformatics—Trim Galore! Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Gong, W.; Pan, X.; Xu, D.; Ji, G.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Cai, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X. Benchmarking DNA Methylation Analysis of 14 Alignment Algorithms for Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing in Mammals. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, F.; Andrews, S.R. Bismark: A Flexible Aligner and Methylation Caller for Bisulfite-Seq Applications. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1571–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.A.; Johnson, A.F.; Rowell, W.J.; Farrow, E.; Hall, R.; Cohen, A.S.A.; Means, J.C.; Zion, T.N.; Portik, D.M.; Saunders, C.T.; et al. Direct Haplotype-Resolved 5-Base HiFi Sequencing for Genome-Wide Profiling of Hypermethylation Outliers in a Rare Disease Cohort. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschendorff, A.E.; Zheng, S.C. Cell-Type Deconvolution in Epigenome-Wide Association Studies: A Review and Recommendations. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinius, L.E.; Acevedo, N.; Joerink, M.; Pershagen, G.; Dahlén, S.E.; Greco, D.; Söderhäll, C.; Scheynius, A.; Kere, J. Differential DNA Methylation in Purified Human Blood Cells: Implications for Cell Lineage and Studies on Disease Susceptibility. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.E.; Irizarry, R.A. Accounting for Cellular Heterogeneity Is Critical in Epigenome-Wide Association Studies. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnero-Montoro, E.; Alarcón-Riquelme, M.E. Epigenome-Wide Association Studies for Systemic Autoimmune Diseases: The Road behind and the Road Ahead. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 196, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surace, A.E.A.; Hedrich, C.M. The Role of Epigenetics in Autoimmune/Inflammatory Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 466419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergstedt, J.; Azzou, S.A.K.; Tsuo, K.; Jaquaniello, A.; Urrutia, A.; Rotival, M.; Lin, D.T.S.; MacIsaac, J.L.; Kobor, M.S.; Albert, M.L.; et al. The Immune Factors Driving DNA Methylation Variation in Human Blood. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houseman, E.A.; Accomando, W.P.; Koestler, D.C.; Christensen, B.C.; Marsit, C.J.; Nelson, H.H.; Wiencke, J.K.; Kelsey, K.T. DNA Methylation Arrays as Surrogate Measures of Cell Mixture Distribution. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, K.; Che, H.; Leroy, K.; Thienpont, B. Benchmarking of Methods for DNA Methylome Deconvolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, K.; Bernatsky, S.; Colmegna, I.; Hudson, M.; Pastinen, T.; Labbe, A.; Greenwood, C.M.T. An Evaluation of Methods Correcting for Cell-Type Heterogeneity in DNA Methylation Studies. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Mills, A.A. Architects of the Genome: CHD Dysfunction in Cancer, Developmental Disorders and Neurological Syndromes. Epigenomics 2014, 6, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Forno, E.; Celedón, J.C.; Chen, W. A Region-Based Method for Causal Mediation Analysis of DNA Methylation Data. Epigenetics 2021, 17, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gils, J.; Magdinier, F.; Fergelot, P.; Lacombe, D. Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome: A Model of Epigenetic Disorder. Genes 2021, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagus, R.; Lusa, L. SMOTE for High-Dimensional Class-Imbalanced Data. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menardi, G.; Torelli, N. Training and Assessing Classification Rules with Imbalanced Data. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2014, 28, 92–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilemobayo, J.A.; Durodola, O.; Alade, O.; Awotunde, O.J.; Olanrewaju, A.T.; Falana, O.; Ogungbire, A.; Osinuga, A.; Ogunbiyi, D.; Ifeanyi, A.; et al. Hyperparameter Tuning in Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review. J. Eng. Res. Rep. 2024, 26, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainio, O.; Teuho, J.; Klén, R. Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Tests for Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santafe, G.; Inza, I.; Lozano, J.A. Dealing with the Evaluation of Supervised Classification Algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2015, 44, 467–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, A.J.; Barnett, A.G. An Introduction to Generalized Linear Models, 4th ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the Caret Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, R.; Ferrisi, S.; Lofaro, D.; Conforti, D. An Overview on the Advancements of Support Vector Machine Models in Healthcare Applications: A Review. Information 2024, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.; Garcia-Lamont, F.; Rodríguez-Mazahua, L.; Lopez, A. A Comprehensive Survey on Support Vector Machine Classification: Applications, Challenges and Trends. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C.; Gnasso, A. A Comparison among Interpretative Proposals for Random Forests. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2021, 6, 100094, Erratum in Mach. Learn. Appl. 2022, 10, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and Regression by RandomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Michel, V.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Vanderplas, J.; Cournapeau, D.; Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou, M.; Ambler, G.; Seaman, S.; De Iorio, M.; Omar, R.Z. Review and Evaluation of Penalised Regression Methods for Risk Prediction in Low-dimensional Data with Few Events. Stat. Med. 2015, 35, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.K.; Narasimhan, B.; Hastie, T. Elastic Net Regularization Paths for All Generalized Linear Models. J. Stat. Softw. 2023, 106, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brauneck, A.; Schmalhorst, L.; Weiss, S.; Baumbach, L.; Völker, U.; Ellinghaus, D.; Baumbach, J.; Buchholtz, G. Legal Aspects of Privacy-Enhancing Technologies in Genome-Wide Association Studies and Their Impact on Performance and Feasibility. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 154, Erratum in Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyke, S.O.M.; Cheung, W.A.; Joly, Y.; Ammerpohl, O.; Lutsik, P.; Rothstein, M.A.; Caron, M.; Busche, S.; Bourque, G.; Rönnblom, L.; et al. Epigenome Data Release: A Participant-Centered Approach to Privacy Protection. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duhm-Harbeck, P.; Köbler, J. Rare Diseases and Data Protection (Part I). In GDPR Requirements for Biobanking Activities Across Europe; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaye, A.; Marcon, Y.; Isaeva, J.; Laflamme, P.; Turner, A.; Jones, E.M.; Minion, J.; Boyd, A.W.; Newby, C.J.; Nuotio, M.L.; et al. DataSHIELD: Taking the Analysis to the Data, Not the Data to the Analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 1929–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarellos, M.; Sheppard, H.E.; Knarston, I.; Davison, C.; Raine, N.; Seeger, T.; Prieto Barja, P.; Chatzou Dunford, M. Democratizing Clinical-Genomic Data: How Federated Platforms Can Promote Benefits Sharing in Genomics. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1045450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baalen, V.; Didden, E.M.; Rosenberg, D.; Bardenheuer, K.; van Speybroeck, M.; Brand, M. Increase Transparency and Reproducibility of Real-World Evidence in Rare Diseases through Disease-Specific Federated Data Networks. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2024, 33, e5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, M.; Bardenheuer, K.; Passey, A.; Schade, R.; Sharma, R.; Hague, C. The Value of Federated Data Networks in Oncology: What Research Questions Do They Answer? Outcomes From a Systematic Literature Review. Value Health 2022, 25, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandl, K.D.; Kohane, I.S. Federalist Principles for Healthcare Data Networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Lee, S.M.; Goldberg, D.; Spix, N.J.; Hinoue, T.; Li, H.-T.; Dwaraka, V.B.; Smith, R.; Shen, H.; Liang, G.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Infinium Human MethylationEPIC v2 BeadChip. Epigenetics Commun. 2023, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaki, S.; Ohmomo, H.; Hachiya, T.; Sutoh, Y.; Ono, K.; Furukawa, R.; Umekage, S.; Otsuka-Yamasaki, Y.; Tanno, K.; Sasaki, M.; et al. Longitudinal DNA Methylation Dynamics as a Practical Indicator in Clinical Epigenetics. Clin. Epigenet. 2021, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coit, P.; Ortiz-Fernandez, L.; Lewis, E.E.; McCune, W.J.; Maksimowicz-McKinnon, K.; Sawalha, A.H. A Longitudinal and Transancestral Analysis of DNA Methylation Patterns and Disease Activity in Lupus Patients. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e143654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urdinguio, R.G.; Torró, M.I.; Bayón, G.F.; Álvarez-Pitti, J.; Fernández, A.F.; Redon, P.; Fraga, M.F.; Lurbe, E. Longitudinal Study of DNA Methylation during the First 5 Years of Life. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.E.; Nicodemus-Johnson, J.; Kim, K.W.; Gern, J.E.; Jackson, D.J.; Lemanske, R.F.; Ober, C. Global DNA Methylation Changes Spanning Puberty Are near Predicted Estrogen-Responsive Genes and Enriched for Genes Involved in Endocrine and Immune Processes. Clin. Epigenet. 2018, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, O.A.; Wang, Y.; Kumari, M.; Zabet, N.R.; Schalkwyk, L. Characterising Sex Differences of Autosomal DNA Methylation in Whole Blood Using the Illumina EPIC Array. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossin, F.; Pinheiro, I.; Żylicz, J.J.; Roensch, J.; Collombet, S.; Le Saux, A.; Chelmicki, T.; Attia, M.; Kapoor, V.; Zhan, Y.; et al. SPEN Integrates Transcriptional and Epigenetic Control of X-Inactivation. Nature 2020, 578, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, T.; Perez de Nanclares, G.; Maher, E.R.; Temple, I.K.; Tümer, Z.; Monk, D.; Mackay, D.J.G.; Grønskov, K.; Riccio, A.; Linglart, A.; et al. Imprinting Disorders: A Group of Congenital Disorders with Overlapping Patterns of Molecular Changes Affecting Imprinted Loci. Clin. Epigenet. 2015, 7, 123, Erratum in Clin. Epigenet. 2016, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Isono, K.; Inoue, T.; Nakamura, A.; Fuke, T.; Yamazawa, K.; Matsubara, K.; Fukami, M.; Ogata, T.; Kawai, T.; Kagami, M. Investigation of Methylation Profiles in Silver–Russell Syndrome to Explore Episignatures. Clin. Epigenet. 2025, 17, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Eshghi, E.; Schenkel, L.C.; Lin, H.; Skinner, C.; Ainsworth, P.; Paré, G.; Siu, V.; Rodenhiser, D.; Schwartz, C.; Sadikovic, B. Clinical Validation of a Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Assay for Molecular Diagnosis of Imprinting Disorders. J. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 19, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Loci | Variant | Array | Article Title | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1p36 deletion syndrome | 1p36, SPEN | Deletion in females | EPIC | SPEN haploinsufficiency causes a neurodevelopmental disorder overlapping proximal 1p36 deletion syndrome with an episignature of X chromosomes in females | [35] |

| 6q24–q25 deletion syndrome | 6q24–q25 | Deletion | 450 k, EPIC | Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions | [36] |

| 7q11.23 duplication syndrome | 7q11.23 | Duplication | 450 k | Symmetrical dose-dependent DNA-methylation profiles in children with deletion or duplication of 7q11.23 | [37] |

| 7q11.23 | Duplication | 450 k, EPIC | Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions | [36] | |

| 7q11.23 | Duplication | 450 k, EPIC | Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders | [26] | |

| 7q11.23 | Duplication | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | |

| 9q34.3 microduplication syndrome | 9q34.3 | Microduplication | EPIC | Refining the 9q34.3 microduplication syndrome reveals mild neurodevelopmental features associated with a distinct global DNA methylation profile | [39] |

| 16p11.2 deletion syndrome | 16p11.2 | Deletion | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] |

| 16p11.2 | Deletion | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | |

| 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (velocardiofacial syndrome) | 22q11.2 | Deletion | EPIC | Identification of a DNA Methylation Episignature in the 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome | [41] |

| 22q11.2 | Deletion | EPIC | Differential methylation of imprinting genes and MHC locus in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome-related schizophrenia spectrum disorders | [42] | |

| 22q11.2 | Deletion | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | |

| 22q11.2 | Deletion | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | |

| Aicardi–Goutières syndrome | RNASEH2B | EPIC | Altered DNA methylation and gene expression predict disease severity in patients with Aicardi–Goutières syndrome | [43] | |

| Alpha-thalassemia/impaired intellectual development syndrome, X-linked | ATRX | 450 k | Identification of epigenetic signature associated with alpha thalassemia/mental retardation X-linked syndrome | [44] | |

| ATRX | 450 k | Genomic DNA methylation signatures enable concurrent diagnosis and clinical genetic variant classification in neurodevelopmental syndromes | [45] | ||

| ATRX | 450 k, EPIC | Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions | [36] | ||

| ATRX | 450 k, EPIC | Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders | [26] | ||

| ATRX | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | ||

| ATRX | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| Arboleda–Tham syndrome | KAT6A | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | |

| KAT6A | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| ARID2-related disorder | ARID2 | EPIC | ARID2-related disorder: further delineation of the clinical phenotype of 27 novel individuals and description of an epigenetic signature | [46] | |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | 450 k | DNA methylation epi-signature and biological age in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder patients | [47] | ||

| Au–Kline syndrome | HNRNPK | Missense and loss of function | EPIC | An HNRNPK-specific DNA methylation signature makes sense of missense variants and expands the phenotypic spectrum of Au-Kline syndrome | [48] |

| Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | 16p11.2 del | 450 k, EPIC | Functional DNA methylation signatures for autism spectrum disorder genomic risk loci: 16p11.2 deletions and CHD8 variants | [49] | |

| CHD8 | |||||

| 450 k | An epigenetic biomarker for adult high-functioning autism spectrum disorder | [33] | |||

| 450 k, EPIC | Epigenetics of autism spectrum disorders: a multi-level analysis combining epi-signature, age acceleration, epigenetic drift and rare epivariations using public datasets | [28] | |||

| 450 k | Screening for rare epigenetic variations in autism and schizophrenia | [50] | |||

| CHD8 | 450 k, EPIC | Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders | [26] | ||

| CHD8 | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | ||

| 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | |||

| Autosomal dominant intellectual developmental disorder—65 (MRD65) | KDM4B | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | |

| KDM4B | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| BAFopathy nonsyndromic | ARID1A, ARID1B | Duplications | EPIC | Microduplications of ARID1A and ARID1B cause a novel clinical and epigenetic distinct BAFopathy | [51] |

| Beck–Fahrner syndrome | TET3 | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | |

| TET3 | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy type 2 (CGL2) | BSCL2 | EPIC | Accelerated epigenetic aging and DNA methylation alterations in Berardinelli–Seip congenital lipodystrophy | [52] | |

| BCL11B-related disease (BCL11B-RD) | BCL11B | EPIC | Clinico-biological refinement of BCL11B-related disorder and identification of an episignature: a series of 20 unreported individuals | [53] | |

| EPIC | |||||

| Beck–Fahrner syndrome | TET3 | EPIC | Deficiency of TET3 leads to a genome-wide DNA hypermethylation episignature in human whole blood | [54] | |

| Blepharophimosis intellectual disability syndrome (BIS) | SMARCA2 | Exons 8 and 9 | EPIC | De novo SMARCA2 variants clustered outside the helicase domain cause a new recognizable syndrome with intellectual disability and blepharophimosis distinct from Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome | [55] |

| SMARCA2 | EPIC | Blepharophimosis with intellectual disability and Helsmoortel-Van der Aa syndrome share episignature and phenotype | [56] | ||

| SMARCA2 | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | ||

| SMARCA2 | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| Börjeson–Forssman–Lehmann syndrome (BFLS) | PHF6 | 450 k, EPIC | Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders | [26] | |

| PHF6 | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | ||

| PHF6 | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| Bohring–Opitz syndrome (BOS) | ASXL | EPIC | DNA methylation signature associated with Bohring-Opitz syndrome: a new tool for functional classification of variants in ASXL genes | [57] | |

| CDK13-related disorder (CDK13-RD) | CDK13 | EPIC | CDK13-related disorder: report of a series of 18 previously unpublished individuals and description of an epigenetic signature | [58] | |

| Cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy, autosomal dominant (ADCADN) | DNMT1 | 450 k | Identification of a methylation profile for DNMT1-associated autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy | [59] | |

| DNMT1 | 450 k | Genomic DNA methylation signatures enable concurrent diagnosis and clinical genetic variant classification in neurodevelopmental syndromes | [45] | ||

| DNMT1 | 450 k, EPIC | Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions | [36] | ||

| DNMT1 | 450 k, EPIC | Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders | [26] | ||

| DNMT1 | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | ||

| DNMT1 | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 2Z (CMT2Z) | MORC2 | EPIC, EPICv2 | Pleiotropic effects of MORC2 derive from its epigenetic signature | [60] | |

| CHARGE syndrome | CHD7 | 450 k | CHARGE and Kabuki syndromes: gene-specific DNA methylation signatures identify epigenetic mechanisms linking these clinically overlapping conditions | [61] | |

| CHD7 | EPIC | Genomic DNA methylation signatures enable concurrent diagnosis and clinical genetic variant classification in neurodevelopmental syndromes | [45] | ||

| CHD7 | 450 k, EPIC | Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions | [36] | ||

| CHD7 | 450 k, EPIC | Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders | [26] | ||

| CHD7 | 450 k, EPIC | Novel diagnostic DNA methylation episignatures expand and refine the epigenetic landscapes of Mendelian disorders | [40] | ||

| CHD7 | 450 k, EPIC | Functional correlation of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles in genetic neurodevelopmental disorders | [38] | ||