1. Introduction

Combat sports such as mixed martial arts, boxing, judo, and karate demand not only superior physical conditioning but also refined cognitive and emotional capacities. Elite athletes in these disciplines must operate effectively under extreme pressure, displaying rapid situational assessment, emotional stability, and precise impulse regulation. These characteristics make combat sport practitioners a valuable model for investigating the biological and psychological foundations of self-regulatory abilities in high-functioning individuals exposed to persistent stressors [

1,

2].

An integrated approach combining genetic, epigenetic, and psychological perspectives provides a multidimensional understanding of individual differences in traits critical to sports performance [

3]. While genetic variation can shape neurotransmitter signaling, stress responsiveness, and decision-making dynamics, epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation reflect long-term adaptations to environmental demands. Psychological assessment captures the behavioral output of these processes. Despite this, research simultaneously examining genetic and epigenetic factors in the context of cognitive–emotional traits in elite athletes remains scarce [

4].

The dopamine transporter gene (

DAT1/SLC6A3) contains a 40-base pair variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism in its 3′-untranslated region, with the 9-repeat (9R) and 10-repeat (10R) alleles being most common. Functional studies suggest that this VNTR can modulate

DAT1 expression by influencing mRNA regulation, although reported effects vary in both direction and magnitude [

5,

6]. Neuroimaging studies have also yielded inconsistent associations between VNTR genotype and striatal dopamine transporter availability, implying that the contribution of a single polymorphism may be modest and dependent on environmental or biological context [

7]. Meta-analyses in behavioral domains, including ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) and impulsivity, support only small effect sizes for this marker [

8]. These observations underscore the need to investigate the VNTR within a broader regulatory framework—including epigenetic mechanisms such as promoter methylation—to better understand how genetic and epigenetic variation jointly influence dopaminergic tone in high-performance populations.

DAT1 promoter methylation can suppress gene expression, thereby modifying dopamine clearance from the synaptic cleft. Aberrant methylation patterns have been associated with psychiatric conditions marked by impaired behavioral control, such as ADHD and substance dependence [

9,

10]. However, little is known about how promoter methylation contributes to personality and self-regulation traits in healthy individuals functioning at elite competitive levels [

11].

In the present study, we examined the combined effects of the

DAT1 VNTR polymorphism and

DAT1 promoter methylation on impulsivity in professional combat sport athletes and matched non-athlete controls. Impulsivity was measured using the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale—Version 11 (BIS-11), which evaluates attentional, motor, and non-planning components [

12]. By integrating molecular and psychological data, we sought to clarify the neurobiological mechanisms underlying self-regulation in elite sport contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study involved 100 male combat athletes (M = 21.96 years, SD = 4.61) and a control group of 109 age-matched healthy male individuals (M = 21.86 years, SD = 3.85). All participants gave written informed consent after being fully briefed on the study’s aims and procedures. To control for potential confounding due to population structure, only individuals of Caucasian ethnicity from the same region of Poland were included in both groups. Psychiatric screening for both groups was conducted using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) to exclude drug addiction, anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric disorders. All participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol and other psychoactive substances for at least 24 h prior to sample collection. Blood samples were collected in the morning hours under standardized laboratory conditions to minimize circadian and environmental variability.

The athlete group consisted of healthy males with no history of psychosis or substance use disorders. Participants were actively involved in one of the following combat sports: mixed martial arts (n = 37), judo (n = 22), boxing (n = 19), karate (n = 14), or kickboxing (n = 8). Recruitment strategies included direct outreach to national-level coaches and athletes, as well as announcements during centralized training camps.

All procedures complied with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Bioethics Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Szczecin (Protocol No. 13/KB/VI/2016, dated 8 December 2016).

2.2. Measures

To measure individual differences in impulsivity, the study employed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (Version 11, BIS-11) [

12]. This 30-item questionnaire requires participants to evaluate how frequently they engage in specific behaviors or thought patterns, using a 4-point scale from “rarely/never” to “almost always/always.” The scale captures three distinct dimensions of impulsivity: attentional (e.g., distractibility and cognitive disorganization), motor (e.g., acting on the spur of the moment), and non-planning (e.g., lack of future orientation or structured thinking). The BIS-11 has been extensively validated and is widely regarded as a gold-standard instrument in research on impulsivity, especially in the context of behavioral regulation and substance-related disorders.

2.3. Genotyping and DNA Methylation Assay

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood collected from combat sport athletes and control participants using a commercial DNA purification kit (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland), following the validated procedure described by Recław et al. (2024) [

11]. All samples were stored at −20 °C until analysis.

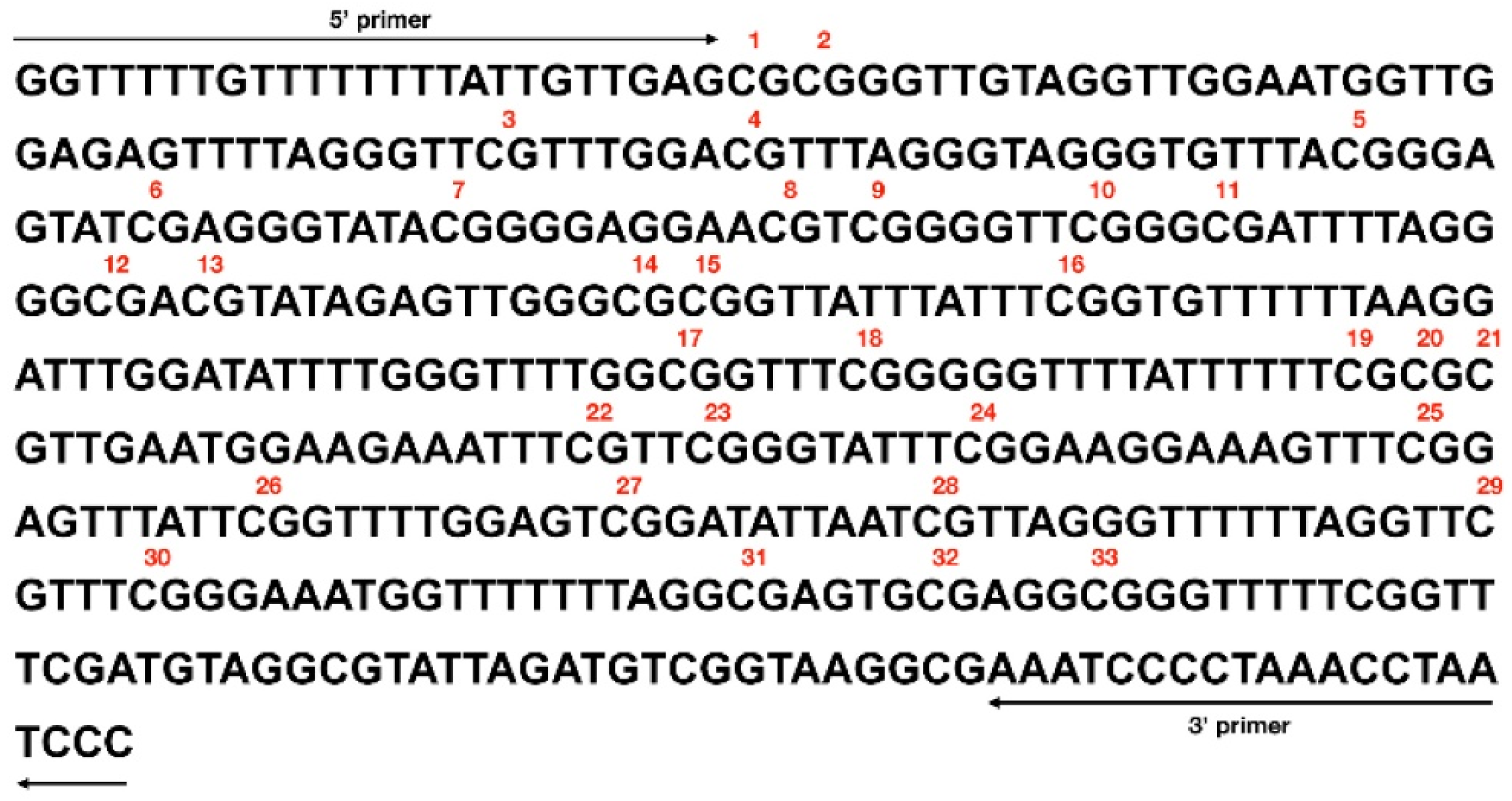

For DNA methylation profiling, 250 ng of genomic DNA from each sample was subjected to sodium bisulfite conversion using the EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Bisulfite-specific PCR was performed on a Mastercycler epgradient S (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) to amplify a 447 bp fragment of the

DAT1 gene promoter region (ENSG00000142319) corresponding approximately to the region between −447 and −1 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS; hg38, chr5:1,445,176, minus strand) and encompassing 33 CpG sites within the CpG island upstream of the TSS, with the reverse primer positioned immediately upstream. Primers were designed in MethPrimer (

http://www.urogene.org/cgi-bin/methprimer/methprimer.cgi, accessed 29 April 2022) and synthesized by Genomed.pl (Warsaw, Poland): forward DATF 5′-GGTTTTTGTTTTTTTTATTGTTGAG-3′ and reverse DATR 5′-AAATCCCCTAAACCTAATCCC-3. Because primer design was optimized for bisulfite conversion efficiency (minimizing cytosine content outside CpG sites) rather than for precise transcript coverage, the TSS position should be considered approximate and is indicated in the text only for genomic reference.

Figure 1 presents the bisulfite-converted sequence, CpG site positions (1–33), and primers.

PCR reactions were prepared in 25 µL volumes containing 100 ng of bisulfite-converted DNA, 10 pmol of each primer, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 µM each dNTP, and 0.8 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 55 s, annealing at 55 °C for 50 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

The resulting amplicons were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI Prism 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Chromatograms were inspected in 4Peaks software, version 1.8 (Nucleobytes, Aalsmeer, The Netherlands). The methylation status of each CpG site was determined from bisulfite sequencing chromatograms as the ratio of cytosine (G) to thymine (A) peaks, calculated as G/(G + A). A CpG site was classified as methylated when the G/(G + A) peak height ratio exceeded 20%, a threshold applied solely to exclude background noise in Sanger sequencing chromatograms and not to indicate full methylation in the heterogeneous blood cell population. Methylation levels below this cut-off are generally regarded as technical signal variation rather than true methylation, and this criterion has been widely validated in bisulfite-based assays performed in molecular biology laboratories operating under EN ISO 15189 standards. Each site was therefore coded as methylated (1) or unmethylated (0).

For each participant, two complementary indices were computed: (i) the percentage of methylated CpG sites, calculated as the proportion of loci exceeding the 20% threshold ((number of methylated sites ÷ 33) × 100), and (ii) the total number of methylated CpG sites (range: 0–33). Both indices were used in subsequent statistical analyses to provide a binary-based, reproducible representation of

DAT1 promoter methylation. Each CpG site was numbered sequentially (CpG1–CpG33) based on its position relative to the transcription start site, and detailed methylation levels for each CpG site are provided in

Table S1.

DAT1 VNTR genotyping in the 3′-untranslated region was performed by conventional PCR using the following primers: forward 5′-TGT GGT GTA GGG AAC GGC CTG AG-3′ and reverse 5′-CTT CCT GGA GGT CAC GGC TCA AGG-3′. Reaction mixtures were prepared as above, and amplification products were separated by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. Gels were run on a horizontal gel electrophoresis unit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 90 V in 1× TAE buffer for 90 min. Bands were visualized under ultraviolet illumination and compared with a DNA ladder (100 bp, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The expected product sizes were 450 bp for the 10-repeat allele and 410 bp for the 9-repeat allele [

13].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for

DAT1 VNTR genotype distributions was tested separately in athletes and controls using an online calculator (

https://wpcalc.com/en/equilibrium-hardy-weinberg/, accessed 12 December 2024). Differences in genotype and allele frequencies between groups were examined using the chi-square test. Between-group differences in BIS-11 scores and the number of methylated CpG sites were assessed with the Mann–Whitney U test due to non-normal variable distributions. A two-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate the effects of group, genotype, and their interaction on BIS-11 subscales and

DAT1 methylation, with Levene’s test confirming variance homogeneity (

p > 0.05). Post hoc analyses were performed using Fisher’s LSD test. Results from a robust two-way ANOVA on aligned rank-transformed data yielded the same pattern of significance, confirming that the findings were not dependent on the normality assumption. Effect sizes are reported as partial eta squared (η

2).

For the variables related to BIS-11 Subscale Scores and

DAT1 Gene Methylation Site Counts, a significance level of 0.01 (0.05/5) was adopted, using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. For the variables related to methylation of the 33 CpG sites included in the

Supplementary Materials, a significance level of 0.0015 (0.05/33) was adopted, using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

DNA methylation data were obtained from an accredited laboratory operating in accordance with EN ISO 15189 standards, which establish international requirements for quality management systems, validation of analytical methods, and control of measurement accuracy and reproducibility in medical laboratories (International Organization for Standardization. EN ISO 15189:2022—Medical laboratories—Requirements for quality and competence. Geneva, Switzerland: ISO; 2022). Data were directly provided in a binary format (methylated = 1, unmethylated = 0), based on a 20% methylation threshold per CpG site, which served as a technical noise filter. Two indices were used in the analyses: (i) the total number of methylated CpG sites (range: 0–33) and (ii) the percentage of methylated CpG sites, reflecting the proportion of loci exceeding this threshold. Analyses were conducted in STATISTICA 13 (Tibco Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) and JASP version 0.95.2 (JASP Team, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for Windows 11 Pro.

4. Discussion

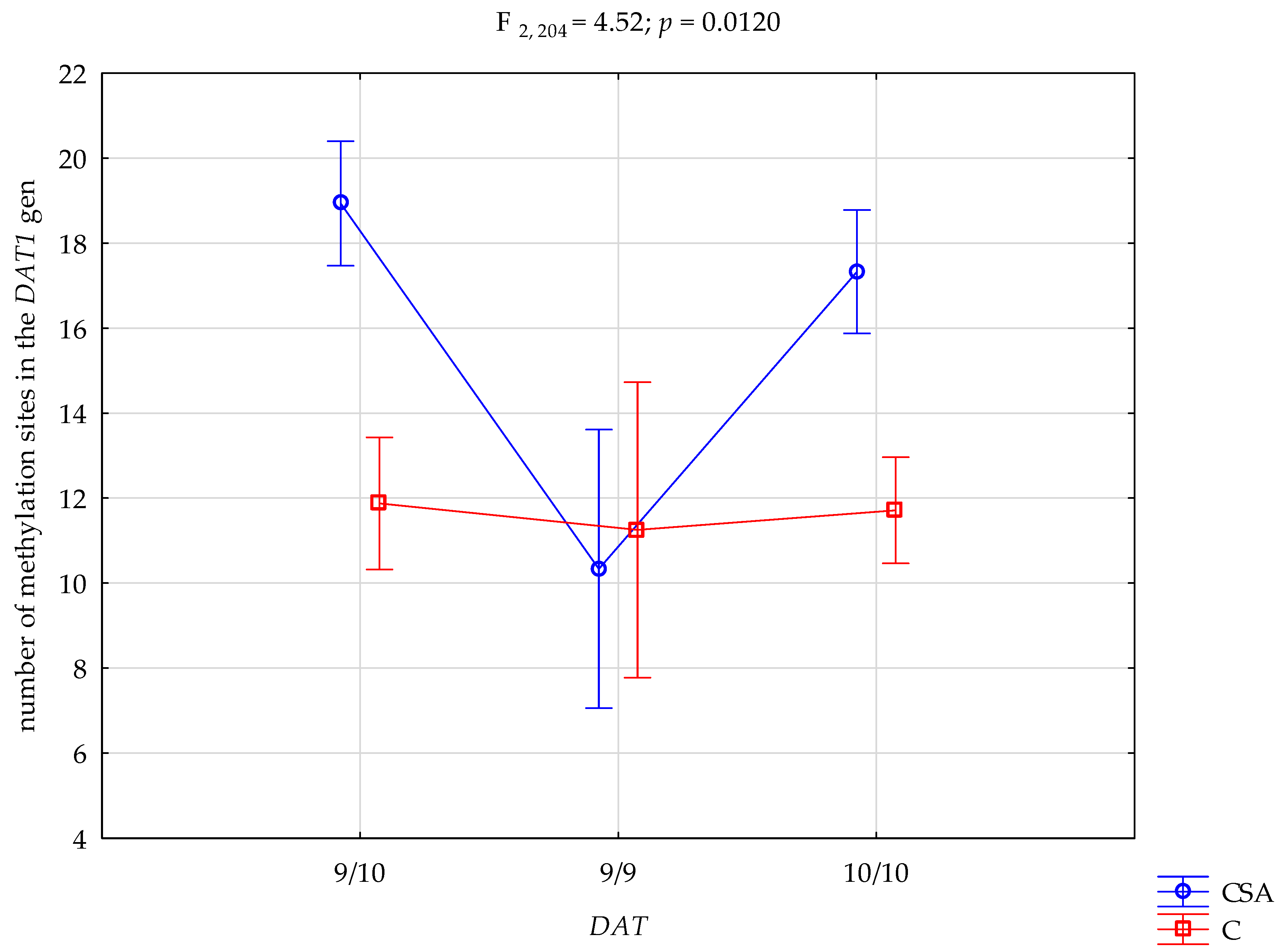

Although the 20% threshold reliably distinguished signal from noise in Sanger sequencing, average methylation levels across individual CpG sites remained low to moderate (<40%), consistent with partial methylation within a heterogeneous blood cell population. Combat sport athletes showed a significantly higher mean number of methylated CpG sites within the

DAT1 promoter compared to controls (17.42 ± 6.40 vs. 11.74 ± 3.80;

p < 0.0001), representing a non-trivial main group effect (η

2 = 0.078). A significant group × genotype interaction (η

2 = 0.042) indicated that methylation patterns differed according to both athletic status and

DAT1 VNTR genotype, with the highest levels in athletes carrying the 9R/10R genotype, followed by 10R/10R, and the lowest in 9R/9R carriers. These findings point to genotype-dependent differences in

DAT1 methylation associated with athletic status. However, not all of the 33 examined CpG sites exhibited uniform group differences, which likely reflects site-specific variability in regulatory sensitivity within the

DAT1 promoter. This underscores the importance of locus-level analyses in epigenetic studies, as aggregate methylation indices may mask biologically meaningful regional patterns. As shown in

Supplementary Table S1, these site-specific variations contributed to the overall between-group difference in methylation levels. Prior work shows that long-term physical training can influence DNA methylation in humans [

14,

15,

16,

17].

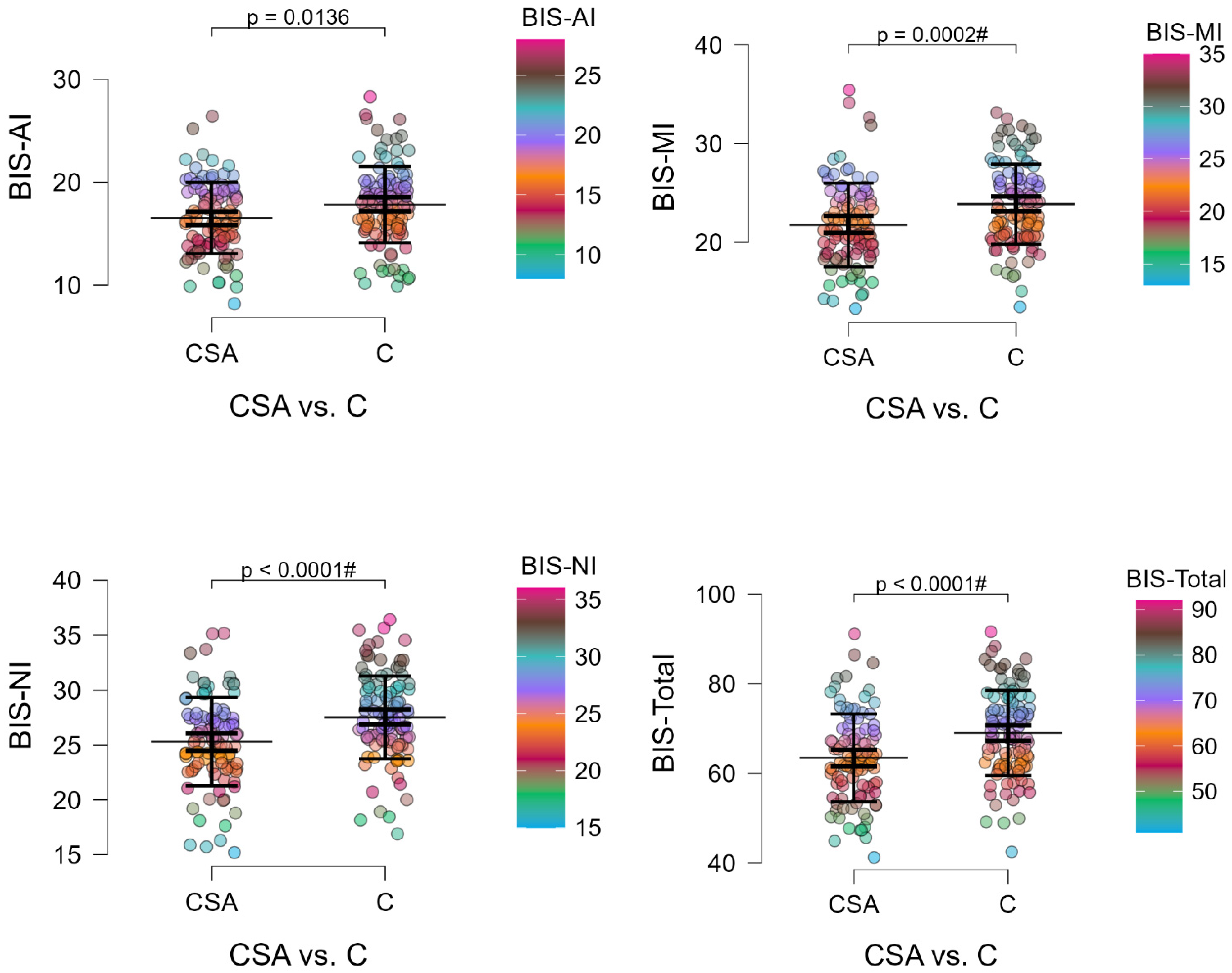

Athletes scored significantly lower than controls on all BIS-11 sub-scales, with no group × genotype interactions, indicating that reduced impulsivity is likely independent of the

DAT1 VNTR genotype. Consistent with this, the main effect of genotype on BIS-11 scores was non-significant across models. This reduction, together with higher promoter methylation in athletes, is consistent with prior reports linking structured athletic training to changes in dopaminergic regulation [

14,

15,

16,

17], although the present findings should be interpreted as correlational.

The lack of genotype frequency differences between groups underscores the importance of considering combined genetic and epigenetic data rather than genetic variation alone. This aligns with evidence that gene–environment processes shape behavioral traits and that DNA methylation has been suggested to mediate links between environmental demands and performance-related cognitive attributes [

15,

17].

Previous research on the

DAT1 VNTR polymorphism and promoter methylation has primarily targeted clinical populations—especially ADHD and substance use disorders. The present findings extend this line of research by documenting systematic between-group differences in a non-clinical, athletic cohort. In particular, athletes carrying the 9R/10R genotype showed the highest methylation, followed by 10R/10R, with the lowest levels in 9R/9R carriers, consistent with reports that DNA methylation is sensitive to sustained environmental demands, including prolonged training [

14,

15,

16]. While our cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, observing this pattern in an elite, non-clinical context suggests a potential extension of earlier work and aligns with broader work indicating that exercise can modify DNA methylation in humans [

14,

16].

The lack of group differences in

DAT1 VNTR genotype frequencies aligns with evidence that the main effects of this polymorphism on behavioral phenotypes are small [

8] (and with imaging work indicating modest effects on striatal

DAT availability [

6]). In contrast, the significant group × genotype interaction for promoter methylation suggests that

DAT1 variation may gain functional relevance when considered alongside epigenetic regulation [

15]. Whether these differences reflect training history, pre-existing predispositions, or residual confounding remains unresolved. In particular, because methylation analysis was performed by an external laboratory using Sanger bisulfite sequencing and we received only binary (methylated/unmethylated) results for each CpG site, we were unable to perform cell-type deconvolution or adjust for blood cell-type heterogeneity—a limitation increasingly recognized in peripheral-blood epigenetic studies.

Regarding impulsivity, athletes showed consistently lower BIS-11 scores across attentional, motor, and non-planning domains relative to controls, in line with prior reports linking structured athletic training to improved self-regulatory and attentional control [

1,

2]. Although few studies have evaluated

DAT1 methylation and impulsivity concurrently [

9,

11], the co-occurrence in our sample of higher promoter methylation and lower impulsivity is compatible with a shared neurobiological pathway involving dopaminergic regulation. Promoter methylation can down-regulate

DAT1 expression—as reported in prior studies [

18,

19,

20]—potentially prolonging synaptic dopamine signaling and supporting cognitive focus and inhibitory control under high demands. Given the study design, these associations should be interpreted as correlational; longitudinal and multi-omics approaches are needed to determine temporal ordering and mechanism.

Mechanistically, increased

DAT1 promoter methylation—linked in prior studies to altered dopamine transporter availability [

9,

10]—may modulate synaptic dopamine signaling and thereby support focus, rapid decision-making, and adaptive motor control in elite combat sports. In our data, methylation was highest in 9R/10R carriers, intermediate in 10R/10R, and lowest in 9R/9R, a genotype-specific pattern consistent with a gene–epigenome interaction model in which

DAT1 VNTR variation influences susceptibility to environmentally induced methylation changes [

20]. Prior work, including in vitro studies on DAT1 VNTR–dependent regulation of transporter density [

5], molecular analyses in clinical populations [

11], and neuroimaging-based assessments of dopaminergic function [

21], suggests that individuals with the 10R/10R genotype may exhibit higher baseline transporter expression. In such cases, methylation-based modulation could be advantageous for balancing arousal and inhibitory control, while training-related environmental demands may further shape methylation profiles at dopamine-related loci [

14,

15,

16,

17]. It should be emphasized, however, that these mechanistic interpretations are speculative and not directly tested in the present study. As this is a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be inferred, and alternative explanations—including gene–environment correlation or unmeasured confounders—cannot be ruled out.

From a behavioral genetics perspective, the co-occurrence in our sample of higher

DAT1 promoter methylation and lower impulsivity is compatible with the broader view that dopaminergic regulation contributes not only to reward sensitivity and motivation but also to self-regulatory traits essential for elite performance [

1,

2,

22]. This profile—strong approach motivation combined with effective behavioral inhibition—has been described in high-level athletes [

1,

2,

17], and our results provide molecular data that are consistent with, but do not directly prove, this characterization. Nevertheless, further work integrating epigenetic, transcriptomic, and neuroimaging approaches will be necessary to clarify how variation at the molecular level translates into functional brain activity and, ultimately, into behavioral performance in the sporting context [

23].

These findings carry practical implications for both sports science and behavioral genetics. In applied sports settings, the observed association between increased

DAT1 promoter methylation and lower impulsivity suggests, but does not demonstrate, that targeted training protocols, psychological interventions, or lifestyle factors influencing epigenetic regulation could contribute to optimizing cognitive control in athletes [

14,

15,

17]. While the present results do not establish causality, they highlight the potential for epigenetic markers to serve as candidate indicators of long-term adaptation to high-performance environments—an idea that would require validation in longitudinal studies examining the stability of methylation patterns over time [

11,

15,

24]. Future research should build on these findings by integrating longitudinal sampling, diverse participant cohorts, and multi-omics approaches combining DNA methylation, transcriptomics, and neuroimaging. Such designs would allow for more precise mapping of the causal pathways linking genetic variation, epigenetic regulation, and behavioral performance in elite athletes. In addition, experimental studies—such as controlled manipulations of training load, psychological stress, or recovery protocols—could help determine whether specific aspects of the athlete environment actively shape the methylation landscape of dopamine-related genes [

25]. These studies should also incorporate rigorous control of potential confounding variables (e.g., diet, circadian timing, substance use, blood cell-type composition) and, where possible, assess methylation patterns in both peripheral tissues and relevant target tissues (e.g., skeletal muscle) to better link molecular variation with performance-related physiology.

Future work should directly assess whether VNTR status and promoter methylation relate to DAT1 transcription. Given the tissue specificity of DAT1, this will likely require neural models (e.g., induced pluripotent stem cell–derived dopaminergic neurons) or neuron-enriched biomarkers (e.g., neuron-derived extracellular vesicles from plasma) rather than bulk peripheral blood. As a pragmatic interim step, peripheral pathway readouts (e.g., expression of dopamine-related genes such as DRD2, COMT, and MAOA in sorted leukocyte subsets) could be explored to provide convergent evidence. While highly preliminary, these findings raise the possibility that epigenetic markers could eventually be developed as indicators of long-term adaptation to training load and competitive pressure. However, these results do not establish a causal relationship. Longitudinal and multi-omics studies are needed to verify whether, and to what extent, the training environment shapes DAT1 methylation and whether such changes translate into lasting differences in impulse control and athletic performance.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes the determination of whether elevated methylation is a consequence of long-term training or a pre-existing characteristic that predisposes individuals to excel in combat sports. Longitudinal designs tracking athletes over their training careers, ideally beginning before elite-level specialization, would help disentangle these possibilities [

11,

24,

25]. Second, the study included only young adult males of Caucasian ethnicity from a single geographic region; while this choice reduced variability linked to sex-related hormonal fluctuations, it substantially limits the generalizability of our findings. Epidemiological studies consistently report higher prevalence rates of behavioral addictions among males [

26,

27], which partly explains the recruitment feasibility and rationale for focusing on a homogeneous male cohort. Nevertheless, sex differences in impulsivity, dopaminergic regulation, and epigenetic profiles are well documented, and the exclusion of female participants should be considered a major limitation. Future studies should replicate the present findings in female cohorts and explore potential sex-specific mechanisms underlying the interaction between

DAT1 methylation, genotype, and impulsivity. Third, the study did not assess

DAT1 expression at the mRNA or protein level, nor did it incorporate neuroimaging or neurotransmitter measurements, meaning that functional inferences about the consequences of methylation remain indirect [

9,

10]. Another limitation is that methylation levels were assessed using bisulfite sequencing, which is considered a semi-quantitative method. While this approach enabled us to examine a relatively broad promoter fragment encompassing 33 CpG sites, the absence of validation using a fully quantitative technique such as bisulfite pyrosequencing represents a limitation. Future studies should incorporate such methods to confirm and refine the present findings. In addition, DNA methylation is tissue-specific. Because

DAT1 is predominantly expressed in the central nervous system, methylation patterns measured in peripheral blood may not fully reflect neural regulation. Nevertheless, peripheral blood is a widely used and practical surrogate tissue in behavioral genetics and sports science. In addition, the 20% methylation threshold applied in this study should be interpreted as a technical noise filter inherent to bisulfite sequencing, not as a biological indicator of full methylation. This methodological approach is widely accepted in human epigenetic and neurobehavioral research, as direct analysis of methylation in brain tissue is ethically and practically unfeasible. Numerous independent studies investigating dopaminergic gene regulation, including

DAT1, have successfully employed peripheral blood as a valid and reproducible biomaterial for assessing methylation signatures associated with behavioral phenotypes [

9,

10,

17,

20]. Moreover, evaluating

DAT1 expression was beyond the scope of the present design because

DAT1 is predominantly expressed in neural tissue and is only weakly detectable in peripheral blood, which was our available biospecimen. While evaluating

DAT1 expression was beyond the scope of this case–control design, future studies integrating methylation and gene expression analyses will be essential to clarify the functional mechanisms underlying the observed epigenetic differences. Finally, potential confounding variables known to influence peripheral DNA methylation—such as smoking status, caffeine or alcohol consumption, circadian timing of sampling, and blood cell-type composition—were not assessed and should be taken into account in future research. Most importantly, the use of outsourced Sanger-based bisulfite sequencing provided only binary methylation calls and precluded the application of reference-based or reference-free cell-type deconvolution algorithms that are currently considered best practice for blood-derived DNA-methylation data. Although this methodological approach has been successfully used numerous times in the dopaminergic epigenetic literature (including our previous high-impact publications), we fully acknowledge that the lack of raw sequencing traces and inability to adjust for leukocyte composition represent a limitation of the present study. Future work from our laboratory will employ in-house next-generation bisulfite sequencing (or pyrosequencing) to enable full statistical adjustment for cell-type proportions and other technical covariates. Despite these limitations, the present study provides novel evidence on epigenetic modulation of the dopaminergic system in elite athletes.