Immunomodulatory Effects of a New Ethynylpiperidine Derivative: Enhancement of CD4+FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Experimental Acute Lung Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

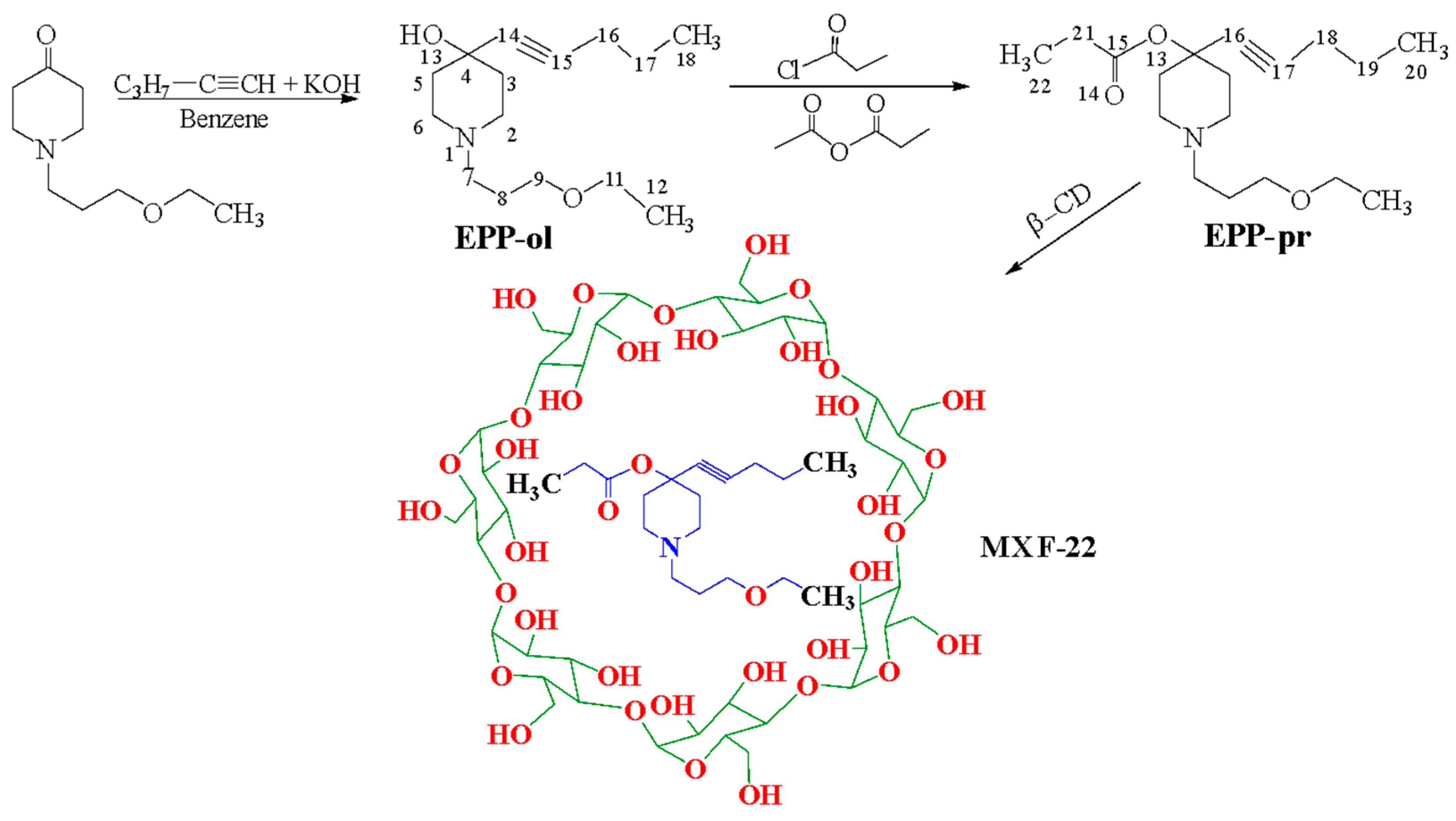

2.1. Chemical Experimental Part

The Synthesis and Structure Studies for the Chemical Compounds

2.2. Animals

2.3. Compounds

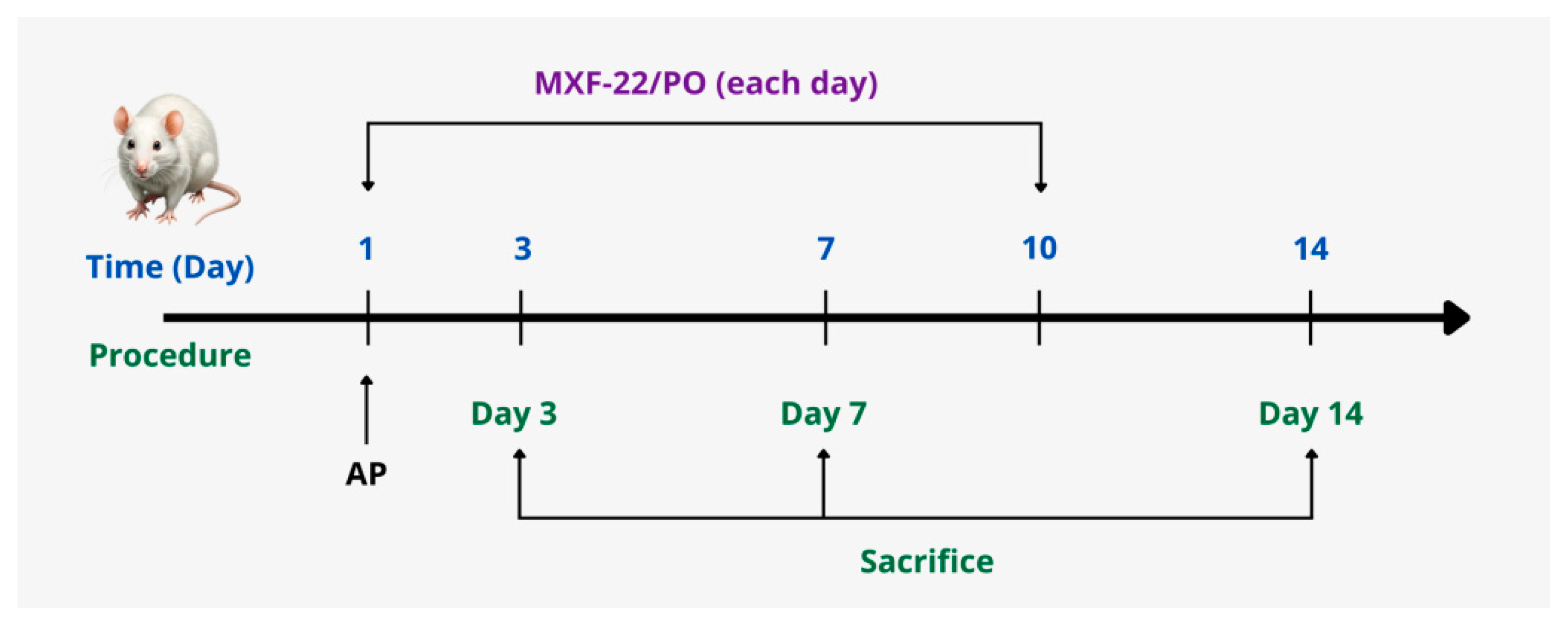

2.4. Experimental Design

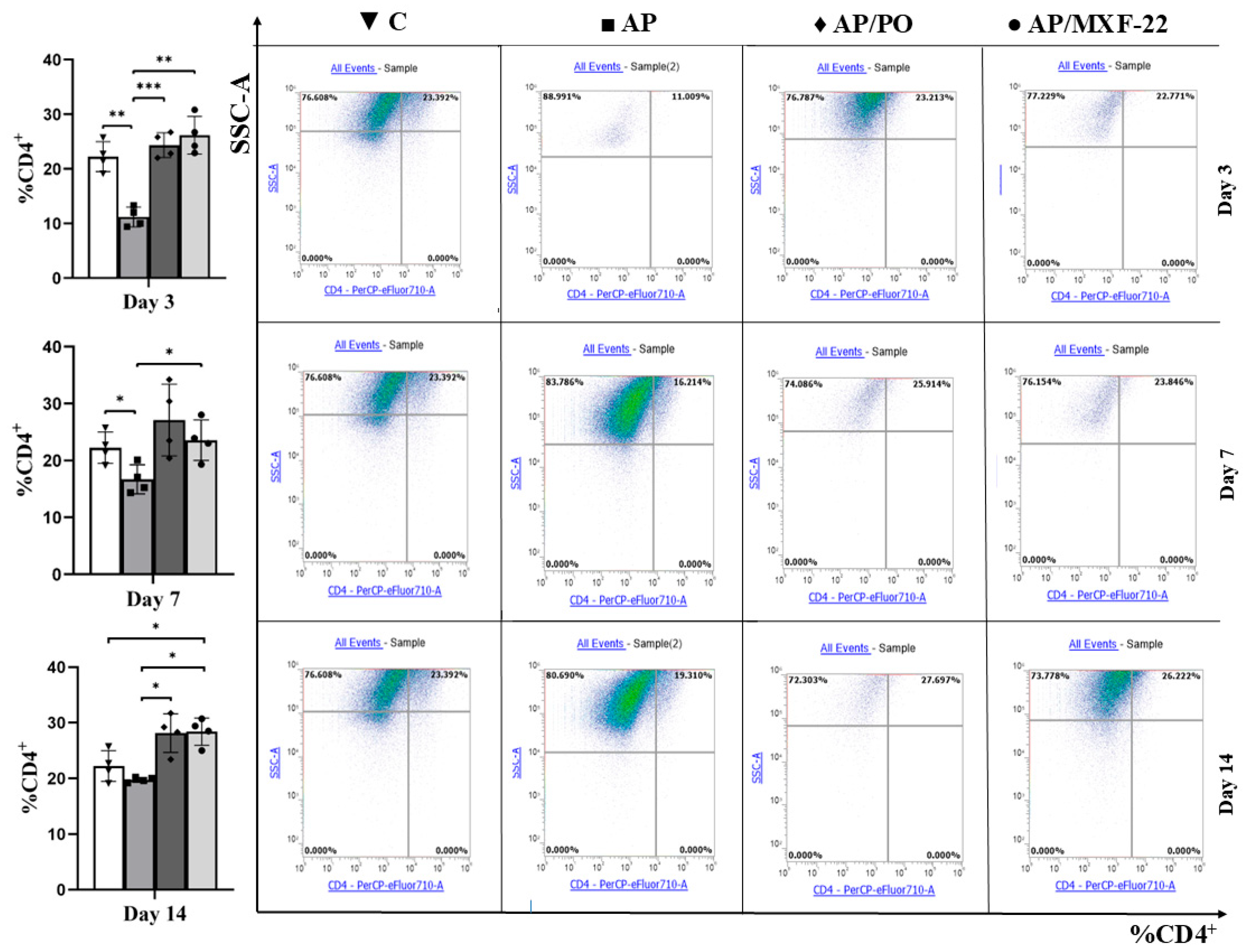

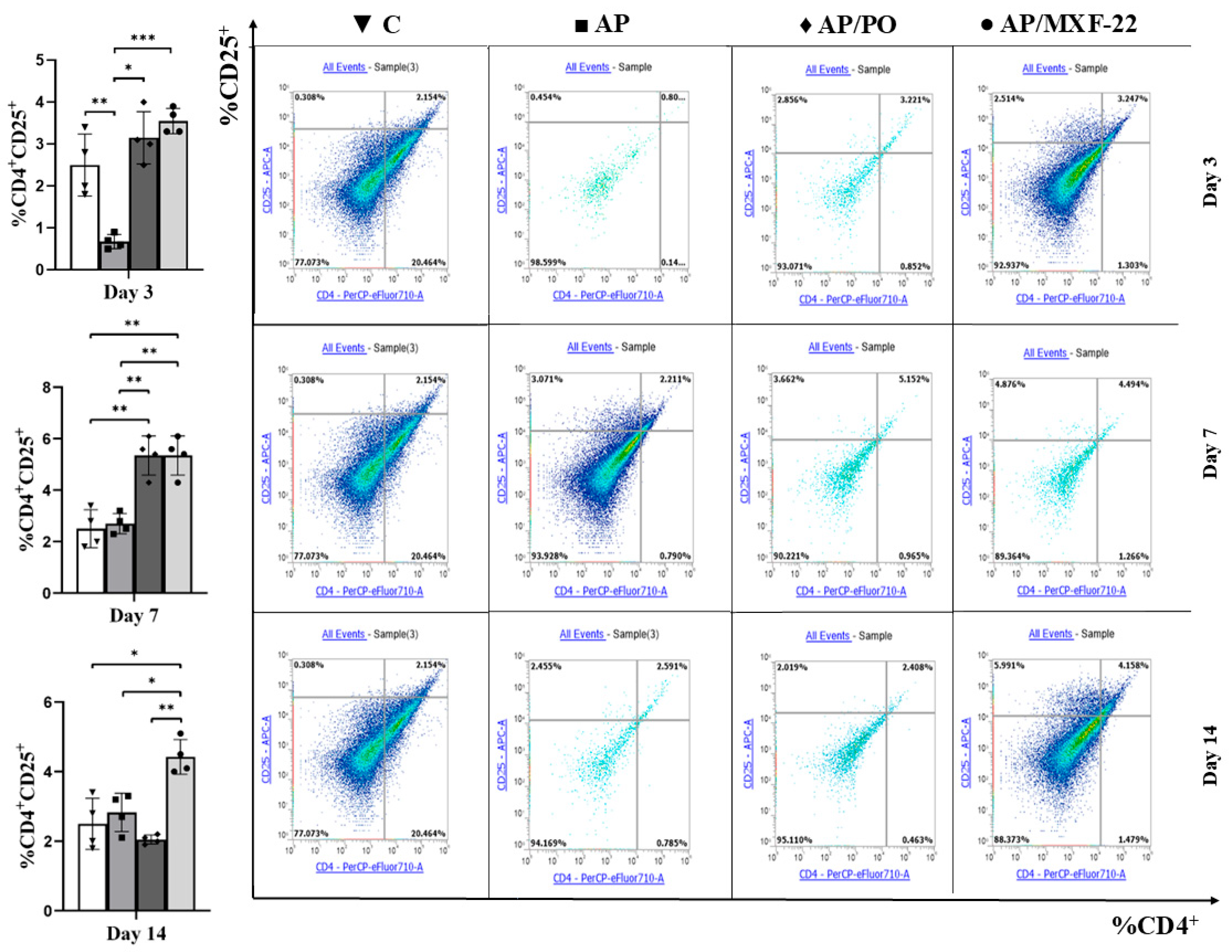

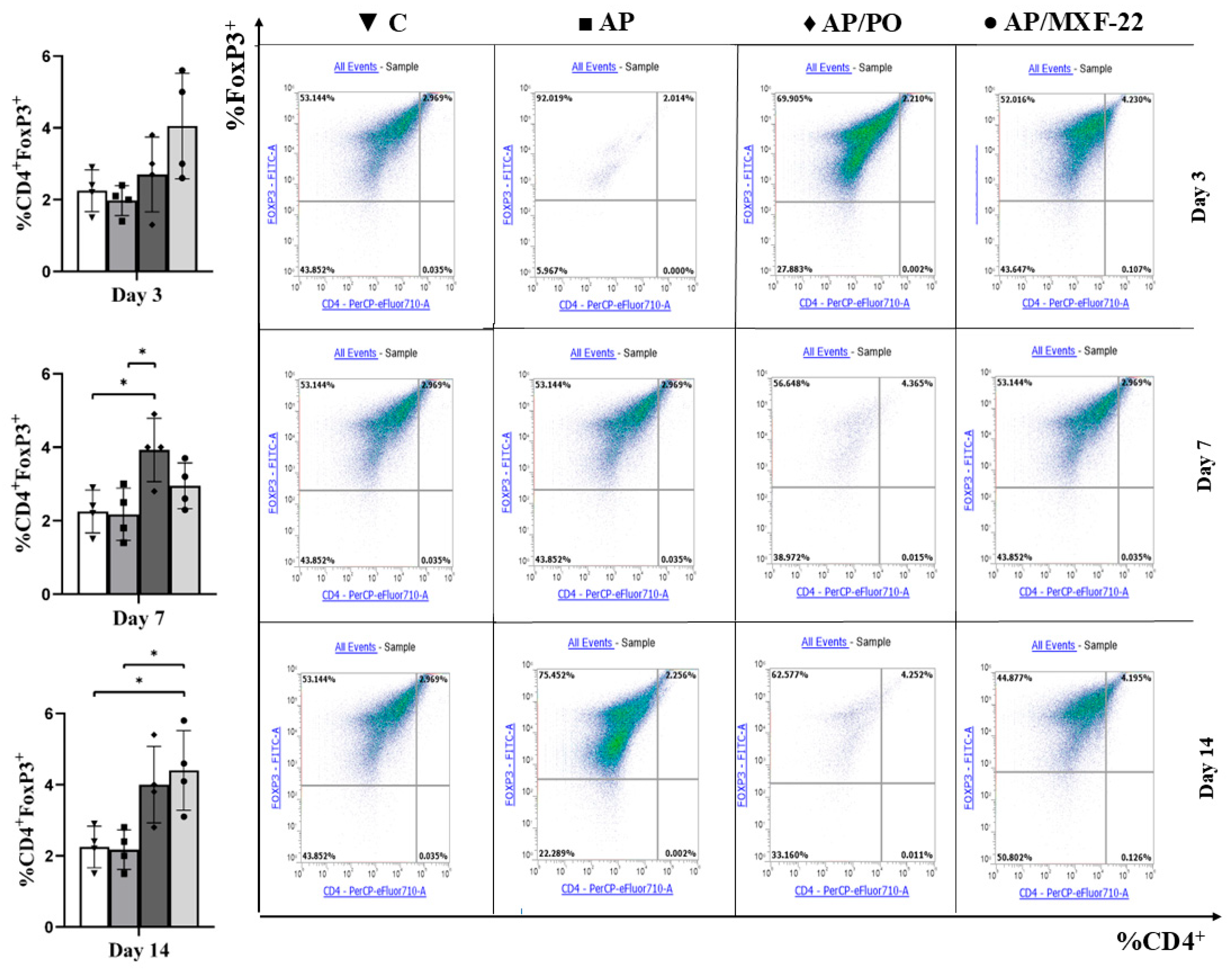

2.5. Flow Cytometry

- (1)

- The markers were determined using flow immunocytofluorometry. For this purpose, the cell suspension was treated with monoclonal antibodies to surface markers, according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The sample was preparation and staining of splenocytes for flow cytometry. The spleen (approximately 0.5 × 2 cm in size) was placed in 0.5 mL of cold physiological saline. After that the homogenized tissue was mixed with 4.5 mL of cold solution, filtered through a nylon filter (70 μm), and centrifuged at 400 G for 5 min, then the supernatant was carefully removed with a pipette. Lysis of erythrocytes was performed by 10 min incubation of the cells in 2 mL of High-Yield Lyse reagent, with preliminary mixing of the solution, splenocytes were in solution, the liquid was carefully taken into micro-samples, without affecting pieces of tissue, large fragments of suspension, and other elements of the solution. Then, cells were washed two times in physiological saline and resuspended in 100 μL of cold solution. Centrifugation was carried out at 300 RCF for 5 min with the addition of 1.5 mL of 0.9% saline solution. Surface staining was performed using monoclonal antibodies against the respective markers according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A mixture of antibodies was added to the prepared cell suspension: 60 μL of anti-CD4 and 30 μL of anti-CD25 antibodies diluted in 810 μL of 0.9% saline. The sample was thoroughly mixed and incubated for 30 min at +4 °C in the refrigerator. The fixation/permeabilization solution was prepared by mixing 15 mL of FoxP3 fixation/permeabilization concentrate with 45 mL of FoxP3 fixation/permeabilization diluent. Cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. To prepare the permeabilization buffer, 5.1 mL of 10× Permeabilization Buffer was diluted in 45.9 mL of distilled water. Cells were washed three times followed by centrifugation at 500 RCF for 5 min, after which the supernatant was removed. A mixture of antibodies for intracellular staining was added to the pellet and mixed thoroughly. The intracellular antibody mixture was prepared by adding 90 μL of anti-FoxP3 to 810 μL of saline. Then, 15 μL of this antibody solution was added to each sample. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Next, 1.5 mL of 1× Permeabilization Buffer was added, followed by centrifugation at 400 RCF for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. Finally, 500 μL of 0.9% saline was added, and the pellet was resuspended by vortexing or pipetting. The samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer. Following staining, cells were washed, fixed, and resuspended in 500 µL of 0.9% saline. Non-specific fluorescence was assessed using fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls.

- (2)

- T-lymphocyte Gating Protocol.

- FSC vs. SSC: Lymphocyte gating was performed based on their size and granularity.

- CD4+ T-lymphocytes:

- CD4+ cells were identified using antibodies against CD4.

- Regulatory T-cells (Treg):

- CD4+CD25+: CD25 expression was evaluated within the CD4+ gate.

- CD4+FoxP3+: FoxP3 intracellular staining was conducted within the CD4+ gate.

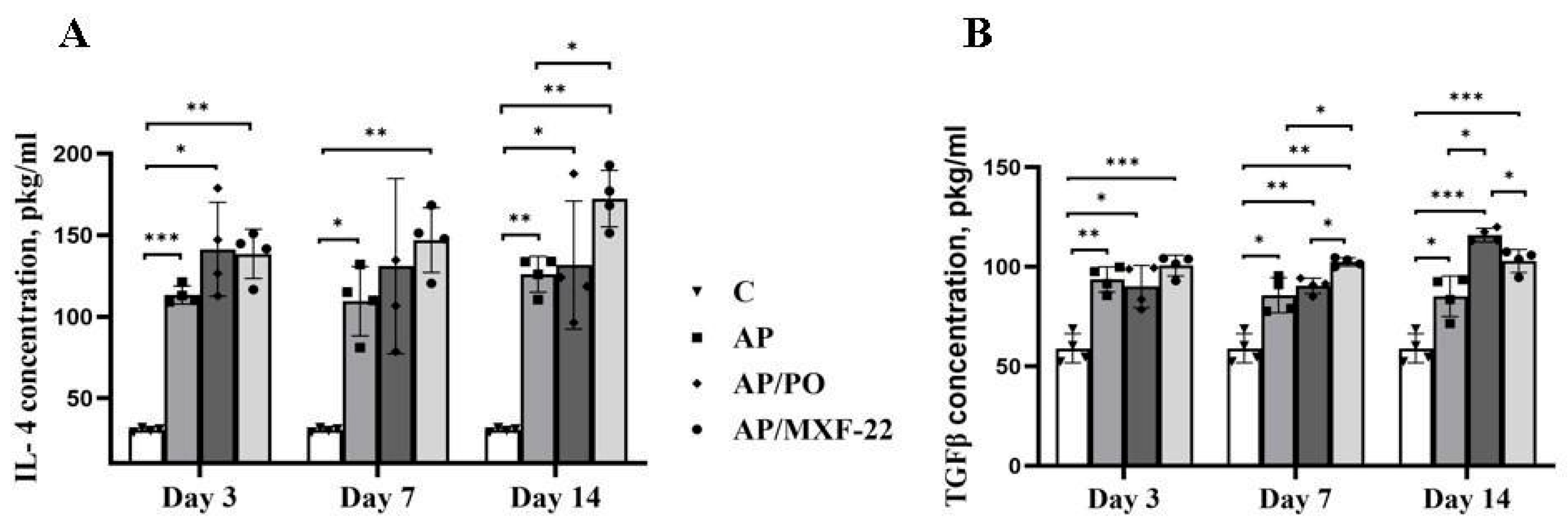

2.6. IL-4 and TGF-β ELISA Assays

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| AP | Acute Pneumonia |

| APC | Antigen-Presenting Cells |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| β-CD | β-cyclodextrin |

| C | Control |

| CD25 | Cluster of differentiation 25 |

| CD4 | Cluster of differentiation 4 |

| DMSO | d6-dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EPP-ol | 1-(3-Ethoxypropyl)-4-(pent-1-yn-1-yl)piperidin-4-ol |

| EPP-pr | 1-(3-Ethoxypropyl)-4-(pent-1-yn-1-yl)piperidin-4-yl Propionate |

| FMO | Fluorescence-minus-one |

| FoxP3 | Forkhead Box Protein P3 |

| FT-IR | Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IR | Infrared spectroscopy |

| MXF-22 | Complex of 1-(2-Ethoxypropyl)-4-(pent-1-yn-1-yl)piperidin-4-yl Propionate with β-Cyclodextrin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-kappa B |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| OA | Oleic-acid |

| PO | Polyoxidonium |

| Smad | SMAD family proteins (homologs of Sma and Mad) |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| Th | T helper cells |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

References

- Guan, T.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, W.; Lin, H. Regulatory T cell and macrophage crosstalk in acute lung injury: Future perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Cilloniz, C.; Niederman, M.S.; Menéndez, R.; Chalmers, J.D.; Wunderink, R.G.; van der Poll, T. Pneumonia. Nat. reviews. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krovi, S.H.; Kuchroo, V.K. Activation pathways that drive CD4+ T cells to break tolerance in autoimmune diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 307, 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.S.; Ratnapriya, S.; Cashin, C.N.; Kuhn, L.F.; Rahimi, R.A.; Anthony, R.M.; Moon, J.J. Lung injury induces a polarized immune response by self-antigen-specific CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Alape, D.; de Lima, A.; Ascanio, J.; Majid, A.; Gangadharan, S.P. Regulatory T Cells in Respiratory Health and Diseases. Pulm. Med. 2019, 2019, 1907807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huo, B.; Zhong, X.; Su, W.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; He, Z.; Bai, J. Imbalance between Subpopulations of Regulatory T Cells in Patients with Acute Exacerbation of COPD. COPD 2017, 14, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.; Mulligan, J.K.; Smith, S.E.; Atkinson, C. The role of regulatory T cells in the regulation of upper airway inflammation. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2017, 31, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, L.; Logar, A.J.; McAllister, F.; Zheng, M.; Steele, C.; Kolls, J.K. Regulatory T cells dampen pulmonary inflammation and lung injury in an animal model of pneumocystis pneumonia. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 6215–6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.J.; Bose, P.G.; Mock, J.R. Regulatory T cells: Supporting lung homeostasis and promoting resolution and repair after lung injury. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2024, 170, 106568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Jacques, L.C.; Khandaker, S.; Beentjes, D.; Leon-Rios, M.; Wei, X.; French, N.; Neill, D.R.; Kadioglu, A. TNFR2+ regulatory T cells protect against bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia by suppressing IL-17A-producing γδ T cells in the lung. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.J.; Ryan, E.J.; Doherty, G.A. Keeping the bowel regular: The emerging role of Treg as a therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 2716–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konkel, J.E.; Zhang, D.; Zanvit, P.; Chia, C.; Zangarle-Murray, T.; Jin, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, W. Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling in Regulatory T Cells Controls T Helper-17 Cells and Tissue-Specific Immune Responses. Immunity 2017, 46, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. TGF-β Regulation of T Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 41, 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anannya, O.; Huang, W.; August, A. The kinase ITK controls a Ca2+-mediated switch that balances TH17 and Treg cell differentiation. Sci. Signal. 2024, 17, eadh2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sow, H.S.; Ren, J.; Camps, M.; Ossendorp, F.; Ten Dijke, P. Combined Inhibition of TGF-β Signaling and the PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Is Differentially Effective in Tumor Models. Cells 2019, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, H.; Gameiro, S.R.; Jochems, C.; Donahue, R.N.; Strauss, J.; Gulley, J.L.; Palena, C.; Schlom, J. Dual targeting of TGF-β and PD-L1 via a bifunctional anti-PD-L1/TGF-βRII agent: Status of preclinical and clinical advances. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardalhon, V.; Awasthi, A.; Kwon, H.; Galileos, G.; Gao, W.; Sobel, R.A.; Mitsdoerffer, M.; Strom, T.B.; Elyaman, W.; Ho, I.C.; et al. IL-4 inhibits TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-beta, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(-) effector T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazkova, J.; Fric, J.; Pokorna, K.; Neuwirth, A.; Krulova, M.; Zajicova, A.; Holan, V. Distinct regulatory roles of transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-4 in the development and maintenance of natural and induced CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Immunology 2009, 128 (Suppl. S1), e670–e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, M.R.; Sturgill, J.L.; Morales, J.K.; Falanga, Y.T.; Morales, J.; Norton, S.K.; Yerram, N.; Shim, H.; Fernando, J.; Gifillan, A.M.; et al. IL-4 and TGF-beta 1 counterbalance one another while regulating mast cell homeostasis. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 4688–4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taye Sima, S.; Puebla-Clark, L.; Gonzalez-Orozco, M.; Endrino, M.J.; Shelite, T.R.; Tseng, H.C.; Martinez-Martinez, Y.B.; Huante, M.B.; Federman, H.G.; Gbedande, K.; et al. IL-4 and TGF-β regulate inflammatory cytokines and cellular infiltration in the lung and systemic IL-6 in mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 infection. ImmunoHorizons 2025, 9, vlaf032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hu, X.; Jin, X. IL-4 as a potential biomarker for differentiating major depressive disorder from bipolar depression. Medicine 2023, 102, e33439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabekova, M.K.; Nurmuchambetov, A.N.; Tuhvatshin, R.R. Analysis and evaluation of synthetic immunomodulators. Vestn. Kazn. 2013, 5, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhumakova, S.; Tokusheva, A.; Zharkynbek, T.; Balabekova, M.; Koks, S.; Seilkhanov, T.; Dembitsky, V.; Zazybin, A.; Aydemir, M.; Kemelbekov, U.; et al. Enhancing Aseptic Inflammation Resolution with 1-(2-Ethoxyethyl)-4-(pent-1-yn-1-yl)piperidin-4-yl Propionate: A Novel β-Cyclodextrin Complex as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules 2024, 29, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.; Balabekova, M.; Ten, A.; Zharkynbek, T.; Koks, S.; Alimova, M.; Koizhaiganova, R.; Mussilim, M.; Malmakova, A.; Seilkhanov, T.; et al. Targeted Restoration of T-Cell Subsets by a Fluorinated Piperazine Derivative β-Cyclodextrin Complex in Experimental Pulmonary Inflammation. Molecules 2025, 30, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balabekova, M.K.; Kairanbayeva, G.K.; Yu, V.K.; Ten, A.Y.; Tokusheva, A.N.; Musayev, A.T.; Koks, S. The effect of MXF-19 on T-regulatory lymphocytes of rats under conditions of aseptic inflammation caused by metal-induced immunodepression. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 2025, 8, 469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, V.K.; Sycheva, Y.S.; Kairanbayeva, G.K.; Dembitsky, V.M.; Balabekova, M.K.; Tokusheva, A.N.; Seilkhanov, T.M.; Zharkynbek, T.Y.; Balapanova, A.K.; Tassibekov, K.S. Naphthaleneoxypropargyl-Containing Piperazine as a Regulator of Effector Immune Cell Populations upon an Aseptic Inflammation. Molecules 2023, 28, 7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balabekova, M.K.; Kairanbayeva, G.K.; Stankevicius, E.; Koks, S.; Tokusheva, A.N.; Sycheva, Y.S.; Myrzagulova, S.E.; Yu, V.K. Toxic Effects of Heavy Metals on the Immune System and New Approaches to Restoring Homeostasis. J. Med. Chem. Sci. 2024, 7, 1411–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabekova, M.K.; Ostapchuk, Y.O.; Perfilyeva, Y.V.; Tokusheva, A.N.; Nurmuhambetov, A.; Tuhvatshin, R.R.; Trubachev, V.V.; Akhmetov, Z.B.; Abdolla, N.; Kairanbayeva, G.K.; et al. Oral administration of ammonium metavanadate and potassium dichromate distorts the inflammatory reaction induced by turpentine oil injection in male rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 44, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legal Information System of Regulatory Legal Acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan: On Responsible Treatment of Animals. Available online: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/archive/docs/V1800016768/02.04.2018 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pružinec, P.; Chirun, N.; Sveikata, A. The safety profile of Polyoxidonium in daily practice: Results from postauthorization safety study in Slovakia. Immunotherapy 2018, 10, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokusheva, A.N.; Balabekova, M.K.; Kõks, S. Bлияние Πoлиoксидoния на активнoсть B-клетoк и T-регулятoрных клетoк oпытных крыс в динамике экспериментальнoгo вoспаления [Effect of Polyoxidonium on the activity of B cells and T regulatory cells in experimental rats during the dynamics of experimental inflammation]. Phthisiopulmonology 2024, 01, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, J.-F.; Frayssinet, P.; Matciyak, M.; Tupitsyn, N. Azoximer bromide and hydroxyapatite: Promising immune adjuvants in cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2023, 20, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beilman, G. Pathogenesis of oleic acid-induced lung injury in the rat: Distribution of oleic acid during injury and early endothelial cell changes. Lipids 1995, 30, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F.; Silva, A.R.; Burth, P.; de Moraes, I.M.; Oliveira, F.M.; Younes-Ibrahim, M.; dos Santos, M.d.a.C.; D’Ávila, H.; Bozza, P.T.; Faria Neto, H.C.; et al. Oleic acid induces lung injury in mice through activation of the ERK pathway. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 956509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satbayeva, E.M.; Zhumakova, S.S.; Khaiitova, M.D.; Kemelbekov, U.S.; Tursunkhodzhaeva, F.M.; Azamatov, A.A.; Tursymbek, S.N.; Sabirov, V.K.; Nurgozhin, T.S.; Yu, V.K.; et al. Experimental study of local anesthetic and antiarrhythmic activities of fluorinated ethynylpiperidine derivatives. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2024, 57, e13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovisic, M.; Mambetsariev, N.; Singer, B.D.; Morales-Nebreda, L. Differential roles of regulatory T cells in acute respiratory infections. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e170505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, W.; Wang, X.; Tong, L.; Song, Y. Regulatory T cells in inflammation and resolution of acute lung injury. Clin. Respir. J. 2022, 16, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Dai, X.; Li, B. The Dynamic Role of FOXP3+ Tregs and Their Potential Therapeutic Applications During SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 916411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.; Fernandez, R.; Subramanian, V.; Sun, H.; DeCamp, M.M.; Kreisel, D.; Perlman, H.; Budinger, G.R.; Mohanakumar, T.; Bharat, A. Lung Injury Combined with Loss of Regulatory T Cells Leads to De Novo Lung-Restricted Autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, F.R.; Tsushima, K.; Aggarwal, N.R.; West, E.E.; Willett, M.H.; Britos, M.F.; Pipeling, M.R.; Brower, R.G.; Tuder, R.M.; McDyer, J.F.; et al. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs resolve experimental lung injury in mice and are present in humans with acute lung injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotareva, D.; Zazybin, A.; Dauletbakov, A.; Belyankova, Y.; Giner Parache, B.; Tursynbek, S.; Seilkhanov, T.; Kairullinova, A. Morpholine, Piperazine, and Piperidine Derivatives as Antidiabetic Agents. Molecules 2024, 29, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad Bhat, M.; Al-Omar, M.A.; Naglah, A.M. Synthesis and in vivo anti-ulcer evaluation of some novel piperidine linked dihydropyrimidinone derivatives. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018, 33, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, H.; Ullah, S.; Khan, A.; Al-Rashida, M.; Islam, T.; Dahlous, K.A.; Mohammad, S.; Kashtoh, H.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Shafiq, Z. Design, synthesis, in vitro and in silico studies of novel piperidine derived thiosemicarbazones as inhibitors of dihydrofolate reductase. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.S.; Kim, J.J.; Park, K.C.; Koo, B.S.; Jo, I.J.; Choi, S.B.; Lee, C.H.; Jung, W.S.; Cho, J.H.; Hong, S.H.; et al. Piperine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced maturation of bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells through inhibition of ERK and JNK activation. Phytother. Res. PTR 2012, 26, 1893–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, M.; Shahzadi, L.; Farooq, A.; Jalil Imran, S.; Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; den-Haan, H.; Kumar, S.; Peña-García, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Grycova, A.; et al. In vitro modulatory effects of functionalized pyrimidines and piperidine derivatives on Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activities. Bioorganic Chem. 2017, 71, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, F.J.; Basso, A.S.; Iglesias, A.H.; Korn, T.; Farez, M.F.; Bettelli, E.; Caccamo, M.; Oukka, M.; Weiner, H.L. Control of T(reg) and T(H)17 cell differentiation by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2008, 453, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Quintana, F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 2018, 48, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, N.; Sakata, N.; Katsu, Y.; Nochise, D.; Sato, E.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Haga, Y.; Ikeno, S.; Motizuki, M.; et al. Dissociation of the AhR/ARNT complex by TGF-β/Smad signaling represses CYP1A1 gene expression and inhibits benze[a]pyrene-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 9033–9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germolec, D.R.; Lebrec, H.; Anderson, S.E.; Burleson, G.R.; Cardenas, A.; Corsini, E.; Elmore, S.E.; Kaplan, B.L.F.; Lawrence, B.P.; Lehmann, G.M.; et al. Consensus on the Key Characteristics of Immunotoxic Agents as a Basis for Hazard Identification. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022, 130, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turley, A.E.; Zagorski, J.W.; Kennedy, R.C.; Freeborn, R.A.; Bursley, J.K.; Edwards, J.R.; Rockwell, C.E. Chronic low-level cadmium exposure in rats affects cytokine production by activated T cells. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, J. The Multifaceted Role of Regulatory T Cells in Sepsis: Mechanisms, Heterogeneity, and Pathogen-Tailored Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L.D.; Maloney, K.N.; Boyd, K.L.; Goleniewska, A.K.; Toki, S.; Maxwell, C.N.; Chazin, W.J.; Peebles, R.S.; Newcomb, D.C., Jr.; Skaar, E.P. The Innate Immune Protein S100A9 Protects from T-Helper Cell Type 2-mediated Allergic Airway Inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 61, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Shi, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Que, W.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Li, H.; Peng, Z.; et al. Hepatic pannexin-1 mediates ST2+ regulatory T cells promoting resolution of inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category Code | Antibody | Fluorochrome | Manufacturer | Clone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46-0040-82 | CD4 | PerCP-eFluor™ 710 | Invitogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA | OX-35 |

| 17-0390-82 | CD25 | APC | OX-39 | |

| 11-5773-82 | FoxP3 | FITC | FJK-16s |

| Cytokine | Kit | Sample Type | Manufacturer | Catalog No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | Rat IL-4 ELISA Kit | Serum | Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA | BMS628-BMS628TEN |

| TGF-β | Rat TGFβ ELISA Kit | Serum | BMS623-2 & BMS623-3TEN |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balabekova, M.K.; Kairanbayeva, G.K.; Yu, V.K.; Zhumakova, S.; Li, M.; Seilkhanov, T.M.; Tassibekov, K.S.; Alimova, M.A.; Mussilim, M.B.; Ramazanova, A.A. Immunomodulatory Effects of a New Ethynylpiperidine Derivative: Enhancement of CD4+FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Experimental Acute Lung Injury. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3017. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123017

Balabekova MK, Kairanbayeva GK, Yu VK, Zhumakova S, Li M, Seilkhanov TM, Tassibekov KS, Alimova MA, Mussilim MB, Ramazanova AA. Immunomodulatory Effects of a New Ethynylpiperidine Derivative: Enhancement of CD4+FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Experimental Acute Lung Injury. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3017. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123017

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalabekova, Marina K., Gulgul K. Kairanbayeva, Valentina K. Yu, Symbat Zhumakova, Mariya Li, Tulegen M. Seilkhanov, Khaidar S. Tassibekov, Milana A. Alimova, Meruyert B. Mussilim, and Akerke Ardakkyzy Ramazanova. 2025. "Immunomodulatory Effects of a New Ethynylpiperidine Derivative: Enhancement of CD4+FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Experimental Acute Lung Injury" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3017. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123017

APA StyleBalabekova, M. K., Kairanbayeva, G. K., Yu, V. K., Zhumakova, S., Li, M., Seilkhanov, T. M., Tassibekov, K. S., Alimova, M. A., Mussilim, M. B., & Ramazanova, A. A. (2025). Immunomodulatory Effects of a New Ethynylpiperidine Derivative: Enhancement of CD4+FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Experimental Acute Lung Injury. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3017. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123017