Hesperidin Reverses Oxidative Stress-Induced Damage in Kidney Cells by Modulating Antioxidant, Longevity, and Senescence-Related Genes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. H2O2 and Hesperidin Treatments

2.3. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) Assay

2.4. Real-Time PCR

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

2.6. Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

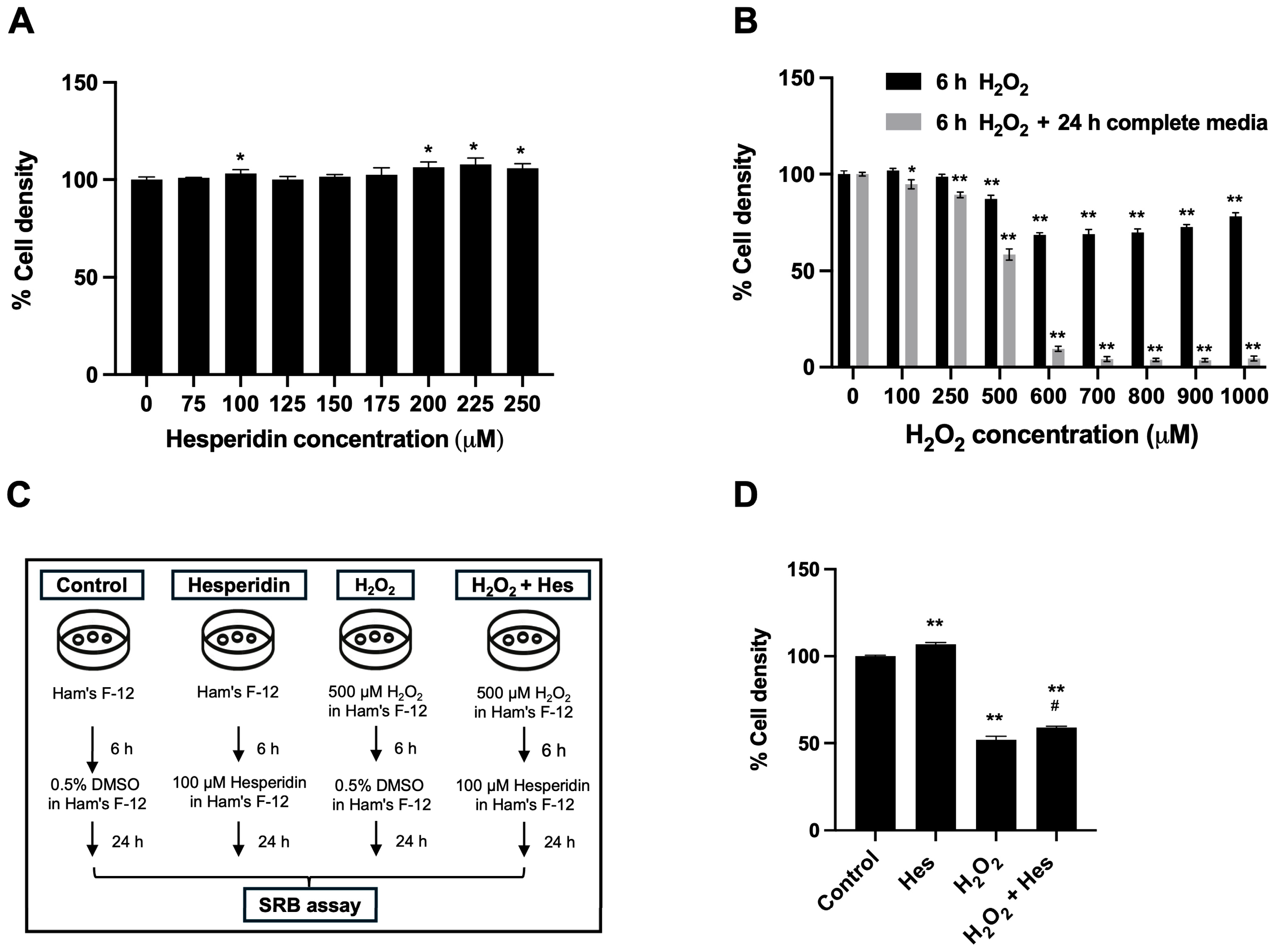

3.1. Hesperidin Restored the Cell Density of Oxidatively Damaged Kidney Cells

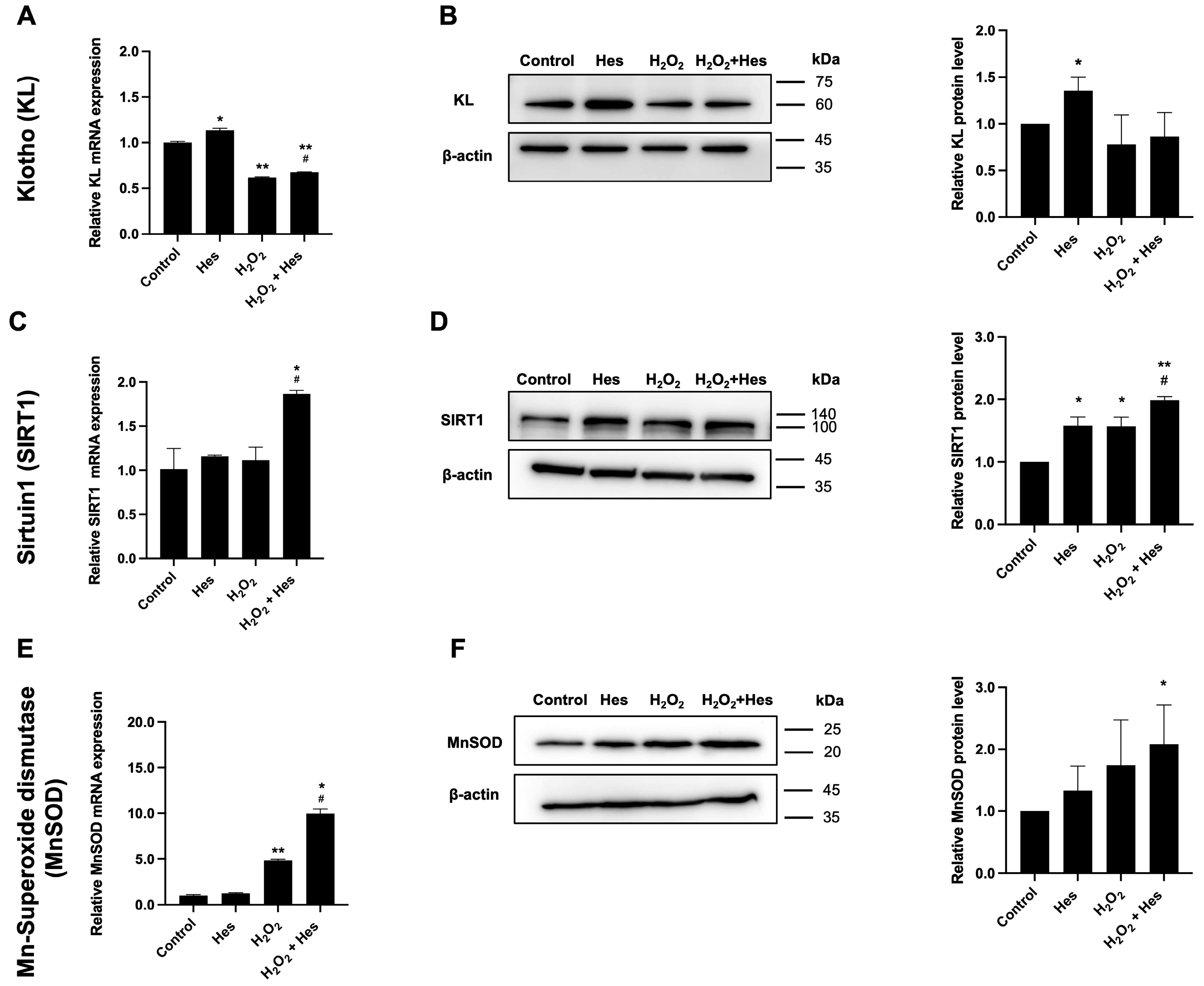

3.2. Hesperidin Upregulated Longevity-Related Genes and Antioxidant Genes in Oxidatively Damaged Kidney Cells

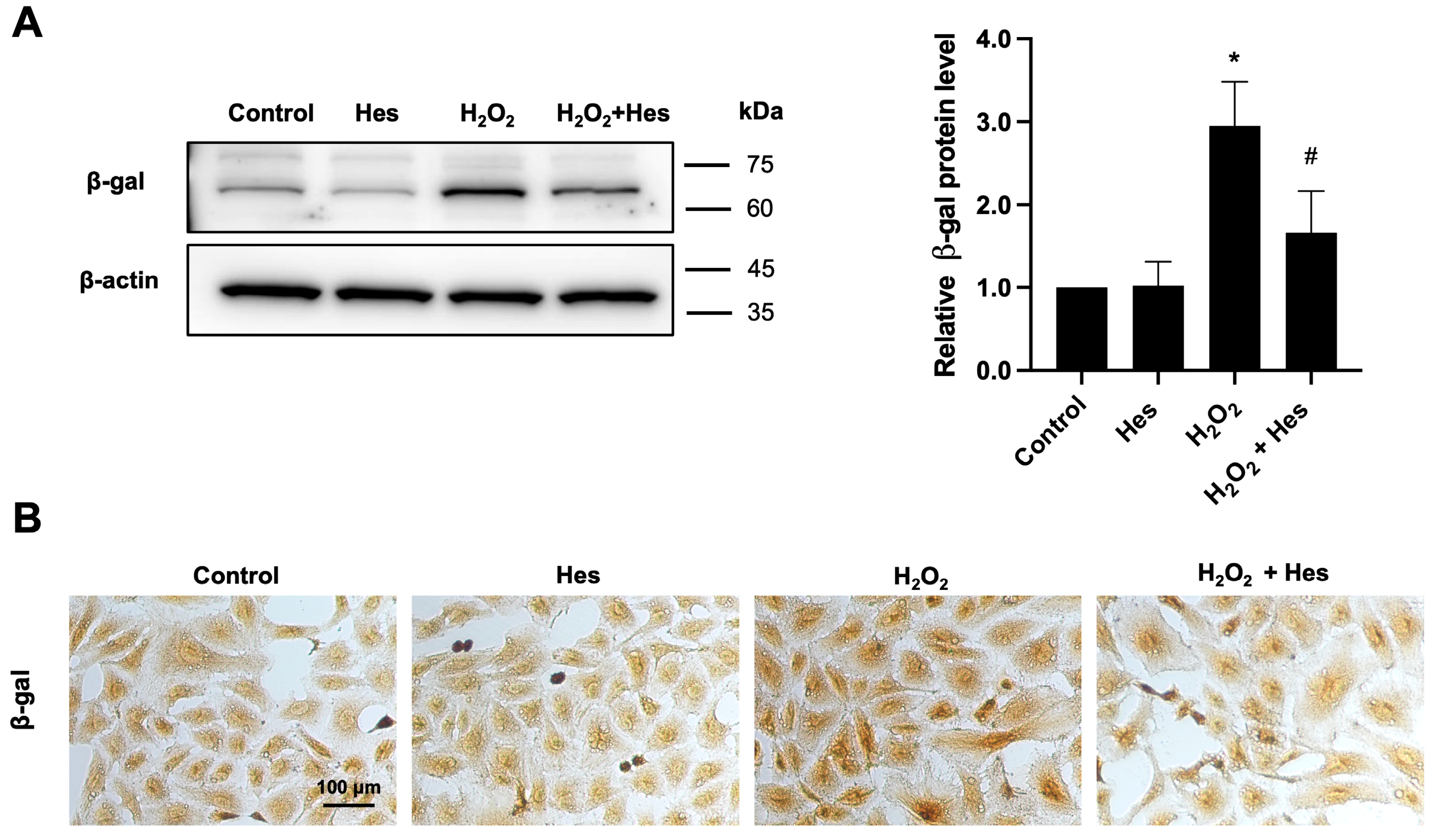

3.3. Hesperidin Reduced β-Galactosidase Expression in Kidney Cells Induced by Oxidative Stress

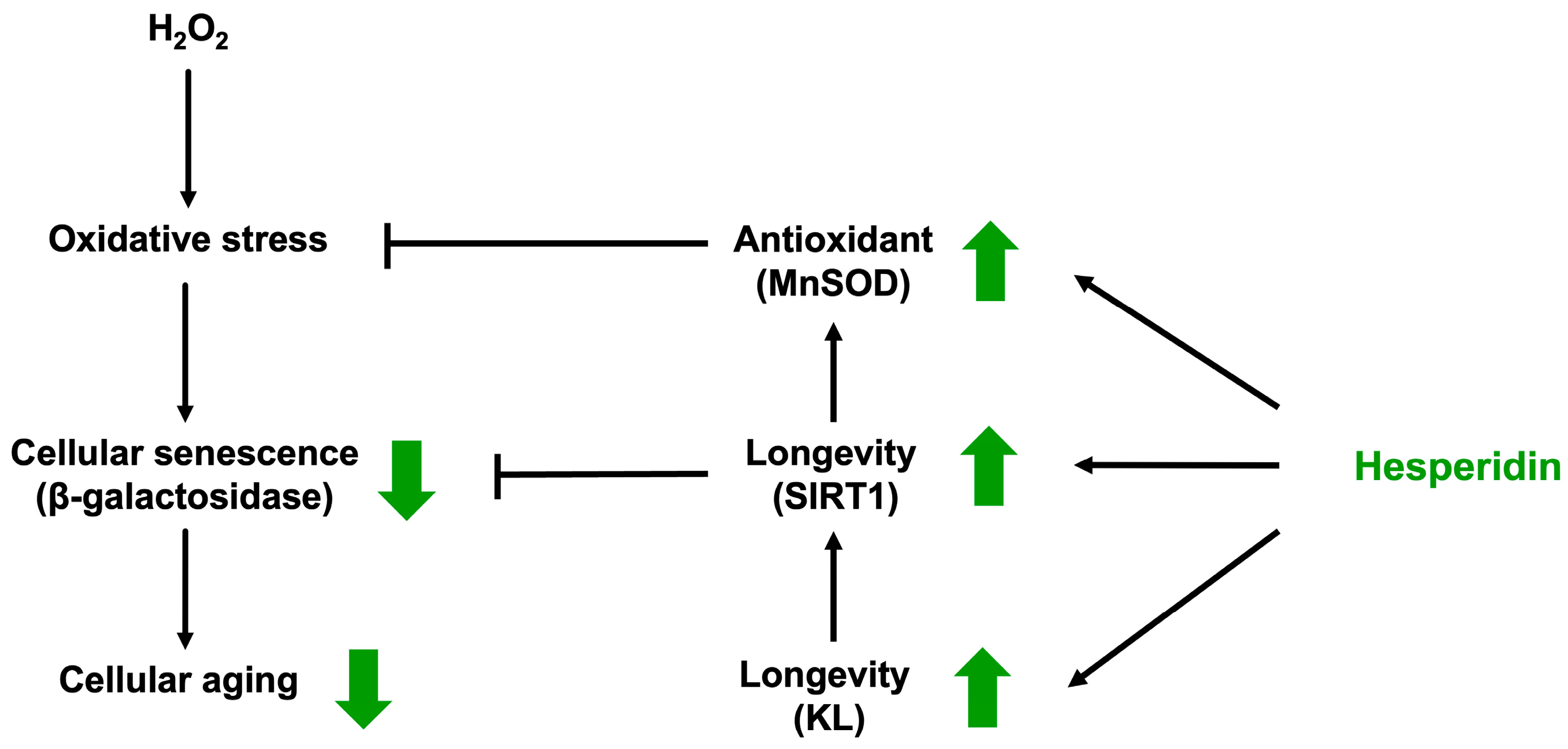

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| KL | Klotho |

| MnSOD | Manganese superoxide dismutase |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1 |

References

- Francis, A.; Harhay, M.N.; Ong, A.C.M.; Tummalapalli, S.L.; Ortiz, A.; Fogo, A.B.; Fliser, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Fontana, M.; Nangaku, M.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: An international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2024, 20, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.R.; Aeddula, N.R. Chronic Kidney Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gounden, V.; Bhatt, H.; Jialal, I. Renal Function Tests. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mallamaci, F.; Tripepi, G. Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression: Between Old and New Concepts. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnani, P.; Remuzzi, G.; Glassock, R.; Levin, A.; Jager, K.J.; Tonelli, M.; Massy, Z.; Wanner, C.; Anders, H.-J. Chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminatti, M.; Tedesco-Silva, H.; Silva Fernandes, N.M.; Sanders-Pinheiro, H. Chronic kidney disease progression in kidney transplant recipients: A focus on traditional risk factors. Nephrology 2019, 24, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanan, R.; Oikawa, S.; Hiraku, Y.; Ohnishi, S.; Ma, N.; Pinlaor, S.; Yongvanit, P.; Kawanishi, S.; Murata, M. Oxidative Stress and Its Significant Roles in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 16, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, F.; Deng, Z. Oxidative Stress: Signaling Pathways, Biological Functions, and Disease. MedComm 2025, 6, e70268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisneros-García, D.L.; Sandoval-Pinto, E.; Cremades, R.; Ramírez-de-Arellano, A.; García-Gutiérrez, M.; Martínez-de-Pinillos-Valverde, R.; Sierra-Díaz, E. Non-traditional risk factors of progression of chronic kidney disease in adult population: A scoping review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1193984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cui, H.; Han, M.; Ren, X.; Gang, X.; Wang, G. Obesity and chronic kidney disease. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 324, E24–E41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, S.; Chinnadurai, R.; Al-Chalabi, S.; Evans, P.; Kalra, P.A.; Syed, A.A.; Sinha, S. Obesity and chronic kidney disease: A current review. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2023, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, G.; Perrone, R.; Fontana, F.; Ligabue, G.; Giovanella, S.; Ferrari, A.; Gregorini, M.; Cappelli, G.; Magistroni, R.; Donati, G. Rethinking Chronic Kidney Disease in the Aging Population. Life 2022, 12, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodošek Hojs, N.; Bevc, S.; Ekart, R.; Hojs, R. Oxidative Stress Markers in Chronic Kidney Disease with Emphasis on Diabetic Nephropathy. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tbahriti, H.F.; Kaddous, A.; Bouchenak, M.; Mekki, K. Effect of Different Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease and Renal Replacement Therapies on Oxidant-Antioxidant Balance in Uremic Patients. Biochem. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wdowiak, K.; Walkowiak, J.; Pietrzak, R.; Bazan-Wozniak, A.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Bioavailability of Hesperidin and Its Aglycone Hesperetin-Compounds Found in Citrus Fruits as a Parameter Conditioning the Pro-Health Potential (Neuroprotective and Antidiabetic Activity)-Mini-Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Wang, J.; Ran, Q.; Lou, G.; Peng, C.; Gan, Q.; Hu, J.; Sun, J.; Yao, R.; Huang, Q. Hesperidin: A Therapeutic Agent For Obesity. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2019, 13, 3855–3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, C.; Han, X.; Tan, Z. Hesperidin ameliorates H(2)O(2)-induced bovine mammary epithelial cell oxidative stress via the Nrf2 signaling pathway. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liao, D.; He, B.; Zhou, G.; Cui, Y. Effects of Citrus Flavanone Hesperidin Extracts or Purified Hesperidin Consumption on Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence From an Updated Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2024, 8, 102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahkesh, H.H.; Badavi, M.; Dianat, M.; Nejaddehbashi, F.; Amini, N.; Hoseinynejad, K. Hesperidin provides dose-dependent renal protection from cisplatin-induced injury, mediated by its regulation of Beclin-1 and LC3-II. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 17981–17988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Yan, J.; Li, X.; Liu, N.; Zheng, R.; Zhong, Y. Update on the Mechanisms of Tubular Cell Injury in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 661076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyuraszova, M.; Gurecka, R.; Babickova, J.; Tothova, L. Oxidative Stress in the Pathophysiology of Kidney Disease: Implications for Noninvasive Monitoring and Identification of Biomarkers. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5478708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, T.; Moriya, J.; Miyazawa, K.; Yamada, S.; Han, J.; Yang, Q.; Guo, X.; Nakahashi, T.; Mizuta, S.; Inoue, S.; et al. Potential of Orally Administered Quercetin, Hesperidin, and p-Coumaric Acid in Suppressing Intra-/Extracellular Advanced Glycation End-Product-Induced Cytotoxicity in Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, T.; Inoue, S.; Kunii, K.; Masauji, T.; Moriya, J.; Motoo, Y.; Miyazawa, K. Advanced Glycation End-Product-Modified Heat Shock Protein 90 May Be Associated with Urinary Stones. Diseases 2025, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.J.; Johnson, G.; Kirk, J.; Fuerstenberg, S.M.; Zager, R.A.; Torok-Storb, B. HK-2: An immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal adult human kidney. Kidney Int. 1994, 45, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujicic, J.; Allen, A.R. Manganese Superoxide Dismutase: Structure, Function, and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.Z.; Shang, Y.C.; Wang, S.; Maiese, K. SIRT1: New avenues of discovery for disorders of oxidative stress. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyra, J.A.; Hu, M.C.; Moe, O.W. Klotho in Clinical Nephrology: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, B.; Jovanovic, I.; Dimitrijevic Stojanovic, M.; Stojanovic, B.S.; Kovacevic, V.; Radosavljevic, I.; Jovanovic, D.; Miletic Kovacevic, M.; Zornic, N.; Arsic, A.A.; et al. Oxidative Stress-Driven Cellular Senescence: Mechanistic Crosstalk and Therapeutic Horizons. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daenen, K.; Andries, A.; Mekahli, D.; Van Schepdael, A.; Jouret, F.; Bammens, B. Oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019, 34, 975–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.-C.; Ye, Y.-Y.; Ji, G.; Liu, J.-W. Hesperidin Upregulates Heme Oxygenase-1 To Attenuate Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Cell Damage in Hepatic L02 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3330–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martemucci, G.; Costagliola, C.; Mariano, M.; D’andrea, L.; Napolitano, P.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Free Radical Properties, Source and Targets, Antioxidant Consumption and Health. Oxygen 2022, 2, 48–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, S.; Combet, E.; Stenvinkel, P.; Shiels, P.G. Klotho, Aging, and the Failing Kidney. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Trejo, S.S.; Gomez-Sierra, T.; Eugenio-Perez, D.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Protective Effect of Curcumin on D-Galactose-Induced Senescence and Oxidative Stress in LLC-PK1 and HK-2 Cells. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-T.; Wang, G.; Ye, L.-F.; Pu, Y.; Li, R.-T.; Liang, J.; Wang, L.; Lee, K.K.H.; Yang, X. Baicalin reversal of DNA hypermethylation-associated Klotho suppression ameliorates renal injury in type 1 diabetic mouse model. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 3329–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Islam, R. Mammalian Sirt1: Insights on its biological functions. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrin, N.; Kaushik, V.K.; Fortier, E.; Wall, D.; Pearson, K.J.; De Cabo, R.; Bordone, L. JNK1 Phosphorylates SIRT1 and Promotes Its Enzymatic Activity. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, Y.; Takemoto, T.; Itoh, K.; Ishida, A.; Yamazaki, T. Dual Role of Superoxide Dismutase 2 Induced in Activated Microglia. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 22805–22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buranasudja, V.; Rani, D.; Malla, A.; Kobtrakul, K.; Vimolmangkang, S. Insights into antioxidant activities and anti-skin-aging potential of callus extract from Centella asiatica (L.). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, G.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. Unraveling the AMPK-SIRT1-FOXO Pathway: The In-Depth Analysis and Breakthrough Prospects of Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh, F.; Moosavi-Saeed, Y.; Yeganeh-Hajahmadi, M. Interaction of Klotho and sirtuins. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 182, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valieva, Y.; Ivanova, E.; Fayzullin, A.; Kurkov, A.; Igrunkova, A. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Detection in Pathology. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.Z.; Li, B.S.; Gao, S.S.; Seo, J.H.; Choi, B.-M. Luteolin inhibits H2O2-induced cellular senescence via modulation of SIRT1 and p53. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, T.; Muroyama, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Murosaki, S. Oral intake of a combination of glucosyl hesperidin and caffeine elicits an anti-obesity effect in healthy, moderately obese subjects: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valls, R.M.; Pedret, A.; Calderon-Perez, L.; Llaurado, E.; Pla-Paga, L.; Companys, J.; Moragas, A.; Martin-Lujan, F.; Ortega, Y.; Giralt, M.; et al. Effects of hesperidin in orange juice on blood and pulse pressures in mildly hypertensive individuals: A randomized controlled trial (Citrus study). Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero-Sarmiento, C.G.; Ortiz-Andrade, R.; Araujo-León, J.A.; Segura-Campos, M.R.; Vazquez-Garcia, P.; Rubio-Zapata, H.; Hernández-Baltazar, E.; Yañez-Pérez, V.; Sánchez-Recillas, A.; Sánchez-Salgado, J.C.; et al. Preclinical Safety Profile of an Oral Naringenin/Hesperidin Dosage Form by In Vivo Toxicological Tests. Sci. Pharm. 2022, 90, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kandhare, A.D.; Mukherjee, A.A.; Bodhankar, S.L. Acute and sub-chronic oral toxicity studies of hesperidin isolated from orange peel extract in Sprague Dawley rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 105, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, V.; Figueira, O.; Castilho, P.C. Hesperidin: A flavanone with multifaceted applications in the food, animal feed, and environmental fields. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 3291–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.P.N.; Timmins, P.; Smith, A.M.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Drug delivery and formulation development of hesperidin: A systematic review. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, Z.; Naser-Nakhaee, Z.; Karimi-Shahrbabak, E.; Cheraghpour, M.; Hedayati, M.; Mohaghegh, S.M.; Ommi, S.; Hekmatdoost, A. Combination therapy of flaxseed and hesperidin enhances the effectiveness of lifestyle modification in cardiovascular risk control in prediabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitomi, R.; Yamamoto, M.; Kumazoe, M.; Fujimura, Y.; Yonekura, M.; Shimamoto, Y.; Nakasone, A.; Kondo, S.; Hattori, H.; Haseda, A.; et al. The combined effect of green tea and alpha-glucosyl hesperidin in preventing obesity: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buakaew, S.; Sakonsinsiri, C.; Lert-itthiporn, W.; Cha’on, U.; Rudtanatip, T.; Kraiklang, R.; Kaewlert, W.; Rattanaseth, P.; Pakdeechote, P.; Thanan, R. Hesperidin Reverses Oxidative Stress-Induced Damage in Kidney Cells by Modulating Antioxidant, Longevity, and Senescence-Related Genes. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123016

Buakaew S, Sakonsinsiri C, Lert-itthiporn W, Cha’on U, Rudtanatip T, Kraiklang R, Kaewlert W, Rattanaseth P, Pakdeechote P, Thanan R. Hesperidin Reverses Oxidative Stress-Induced Damage in Kidney Cells by Modulating Antioxidant, Longevity, and Senescence-Related Genes. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123016

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuakaew, Supansa, Chadamas Sakonsinsiri, Worachart Lert-itthiporn, Ubon Cha’on, Tawut Rudtanatip, Ratthaphol Kraiklang, Waleeporn Kaewlert, Pornpattra Rattanaseth, Poungrat Pakdeechote, and Raynoo Thanan. 2025. "Hesperidin Reverses Oxidative Stress-Induced Damage in Kidney Cells by Modulating Antioxidant, Longevity, and Senescence-Related Genes" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123016

APA StyleBuakaew, S., Sakonsinsiri, C., Lert-itthiporn, W., Cha’on, U., Rudtanatip, T., Kraiklang, R., Kaewlert, W., Rattanaseth, P., Pakdeechote, P., & Thanan, R. (2025). Hesperidin Reverses Oxidative Stress-Induced Damage in Kidney Cells by Modulating Antioxidant, Longevity, and Senescence-Related Genes. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3016. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123016